Vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting tumors (VIPoma) are rare neuroendocrine tumors (incidence of 0.05–0.2/100,000/yr1) first described by Werner and Morrison presenting as a syndrome of watery diarrhea, hypokalemia and achlorhydria.2 While about 95% of VIPomas arise from the pancreas, some have extra-pancreatic sources.3,4 VIP-producing pheochromocytomas are extremely rare, with no more than a few cases reported to this date.5 Due to its several manifestations, management of both conditions can prove to be challenging. We report the case of a woman with a rare VIP-secreting pheochromocytoma presenting as chronic diarrhea and severe hypokalemic metabolic acidosis.

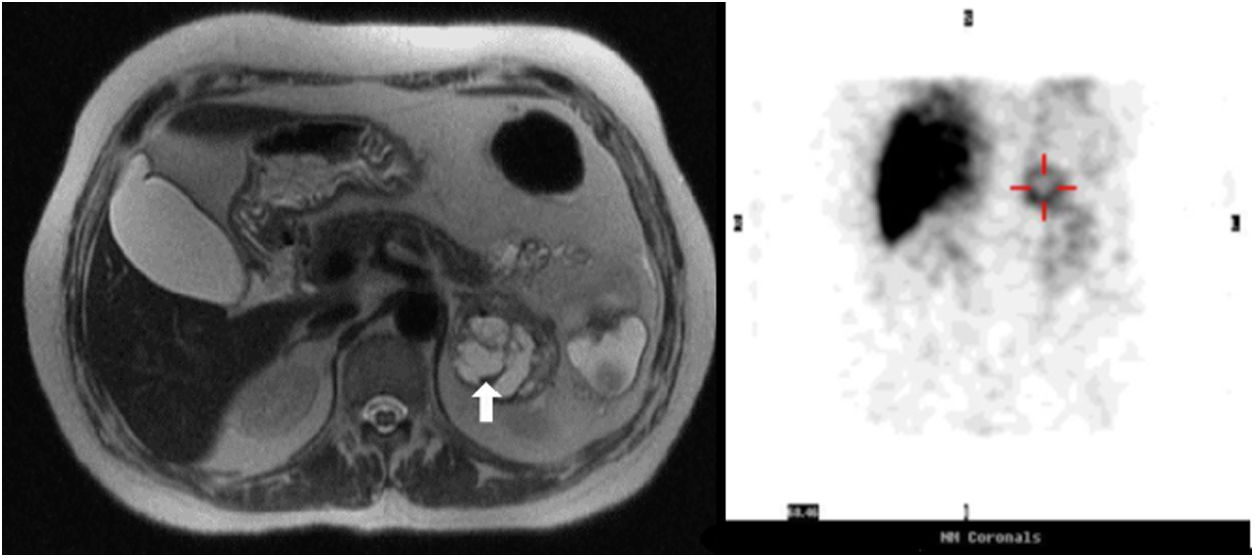

A 63-year-old female was admitted to the Emergency Department for worsening profuse watery diarrhea despite fasting associated with weight loss (14% of total body weight in three months). Upon examination, she was found to be dehydrated and analytical revealed acute kidney injury and hypokalemic metabolic acidosis [K 2.8mEq/L, (reference range (RR) 3.4–5.1); pH 6.9 (RR 7.35–7.45)] requiring intensive intravenous potassium replacement. No increase in inflammatory parameters was found. Mild hypercalcemia (10.9mg/dL at admission, RR 8.9–10.0) remained after correction of dehydration (10.1mg/dL), associated with a decreased parathyroid hormone (4.3pg/mL, RR 15.0–68.3) and normal levels of parathyroid-related protein (<0.5pmol/L, RR<1.3). Stool culture and parasitology were negative and endoscopic studies revealed no abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 6cm heterogeneous left adrenal mass, and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 5.2cm partially cystic mass with a hyperintense solid component on T2 (Fig. 1).

She had a history of episodic headaches accompanied by hypertensive crisis (systolic blood pressure>220mmHg) three years ago, which resolved after the onset of diarrhea. In the meantime, diabetes mellitus (DM) was diagnosed and initially controlled with metformin 2000mg and pioglitazone 15mg daily. Metabolic control has substantially worsened since the onset of diarrhea: HbA1c 9.2% (RR<6.5) with 40 I.U. of insulin glargine, alogliptin 25mg and pioglitazone 15mg daily.

Analysis of the urinary specimen revealed markedly elevated metanephrine (1870μg/24h, RR 45–290) and nor-metanephrine (2388μg/24h, RR 82–500). VIP plasma levels were elevated, 113pmol/L (RR<30), as well as chromogranin A (>700ng/mL, RR<100). 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan was performed because it was readily available, revealing high uptake at the topographical location of the left adrenal gland (Fig. 1).

Diarrhea responded poorly to loperamide. The response to treatment with octreotide was impressive, as the patient stopped intravenous fluids, and dehydration and hypokalemia were treated with a dosage of 100 mcg every 8h. Treatment with octreotide also led to substantial improvements in glycemic control, with a reduction of more than 30% in the total daily insulin dose. Alpha blockade was initiated with phenoxybenzamine, titrated up to 30mg twice a day, when optimal hemodynamic control was achieved.

Two weeks later, the patient underwent laparoscopic left adrenalectomy without complications. Histological examination revealed a 5.2cm pheochromocytoma, Ki67 1%, PASS 0. Immunohistochemistry of neoplastic cells showed positivity to chromogranin, synaptophysin, bcl-2 and somatostatin. After surgery, the patient became asymptomatic and plasma VIP and urinary fractionated metanephrine levels normalized (VIP 16.9pmol/L; metanephrine 59μg/24h; and normetanephrine 169μg/24h). Two years after surgery, the patient remains disease-free, with no need for antihypertensive therapy and in-target glycemic control with metformin 1700mg/day (HbA1c 6.8%). The analyzes revealed normal calcium, PTH and vitamin D levels (9.1–9.4mg/dL, 33.1pg/mL, and 25ng/mL, respectively).

We report the case of a middle-aged woman with a history of hypertensive crisis, probably caused by catecholamine excess, which resolved when symptoms related to VIP appeared. Its resolution coinciding with the onset of diarrhea might be explained by the increased secretion of VIP, which has vasodilating properties. VIP not only inhibits the absorption of water and electrolytes by the jejunum and the colon but also increases net intestinal secretion, causing secretory diarrhea.6

Coincidental diagnosis of DM with hypertensive crisis is justified, in part, by the pheochromocytoma induced hyperglycemia, and its worsening with the onset of VIP-related symptoms raises the question that the increased glycogenolytic activity of the VIP may play an important role, probably due to its structural homology with glucagon.6 Also, achievement of better glycemic control with somatostatin analog (SSA) treatment supports our hypothesis, since SSAs are associated with hyperglycemia in other contexts.

Although the responsiveness of VIP-secreting pheochromocytomas to SSA has been questioned by Quarles et al.7 due to a reported scarcity of somatostatin receptors, our patient had an excellent response with a relatively small dose of octreotide, with a drastic reduction in the number of dejections, reaching normokalemia with no acid-base disorders. In addition, control of diabetes was significantly improved. In light of our results, a SSA treatment trial might be beneficial as a bridge to surgery for symptom and metabolic control.

Notably, hypercalcemia remained after correction of dehydration, so there may be other pathophysiological mechanisms behind this disorder. In fact, hypercalcemia is present in up to 50% of patients with VIPoma,8 as a stimulatory effect of VIP on bone resorption has been suggested.5,9

Cure was achieved with surgery, and glycemic control was remarkably improved, according to previous reports of up to 90% of patients with pheochromocytoma who achieved “cure” of type 2 diabetes after surgery.10

Immunohistochemistry for VIP was not performed due to the difficult pathologic technique and a negative result would not rule out the diagnosis. Considering that the diagnosis was supported by typical clinical manifestations, high preoperative plasma VIP levels, clinical improvement with SSA and resolution after surgery, further study is not necessary.

This rare case illustrates the diverse and contrasting manifestations of VIP-secreting pheochromocytomas, since hormones can exert synergistic or antagonizing effects depending on the target site. The complexity and intricacy of these situations require a multidisciplinary team approach, including endocrinologists, internists and endocrine surgeons, in order to provide the best care available to each patient.

Authors’ contributionsFSC drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical standardsWritten informed consent for publication was obtained.

FundingThis research received no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the physicians who followed our patient.