Total bile acid (TBA) is associated with portal hypertension, a risk factor for post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF). We conducted this study to clarify whether TBA is also associated with PHLF in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

MethodsWe recruited patients with HCC and Child-Pugh class A, who underwent liver resection, and applied multivariate analyses to identify risk factors for PHLF.

ResultsWe analyzed data from 154 patients. The prevalence of PHLF was 14.3%. The median maximum tumor diameter was 5.1 cm (2.9–6.9 cm). The proportions of patients with elevated TBA levels (P = 0.001), severe albumin-bilirubin (AIBL) grades (P = 0.033), and low platelet counts (P = 0.031) were significantly higher within the subgroup of patients with PHLF than in the subgroup without PHLF. The multivariate analysis results suggest that TBA level (OR, 1.08; 951.03–1.14; P = 0.003) and MRI tumor diameter (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01–1.35; P = 0.038) are independent preoperative risk factors for PHLF. The TBA levels correlated with the indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes (P = 0.001) and the effective hepatic blood flow (P < 0.001), two markers of portal hypertension. However, TBA levels did not correlate with tumor diameter (P = 0.536).

ConclusionsCompared to ICG R15 and AIBL score, preoperative TBA was risk factor for PHLF in Chinese patients with HCC, and it may impact PHLF through its potential role as a marker of portal hypertension.

Los ácidos biliares totales (ABT) están asociados con la hipertensión portal, un conocido factor de riesgo para la insuficiencia hepática post-hepatectomía (IHPH). Sin embargo, no está claro si el ABT está relacionado con la IHPH en pacientes con carcinoma hepatocelular (CHC). Por este motivo, realizamos este estudio.

MétodosSe reclutaron pacientes con CHC y Child-Pugh de clase A que se sometieron a resección hepática en un hospital de referencia. Se utilizaron análisis multivariantes para identificar los factores de riesgo de IHPH.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 154 pacientes con CHC y Child-Pugh de clase A, con una prevalencia de IHPH del 14,3%. El diámetro máximo mediano del tumor fue de 5,1 (2,9, 6,9) cm. Los pacientes con IHPH presentaron un porcentaje significativamente mayor de niveles elevados de ABT (P = 0,001), grado severo de albúmina-bilirrubina (AIBL) (P = 0,033) y disminución del recuento de plaquetas (P = 0,031). El análisis multivariante mostró que el nivel de ABT (OR, 1,08, IC 95%: 1,03-1,14; P = 0,003) y el diámetro tumoral en la resonancia magnética (OR, 1,17, IC 95%: 1,01-1,35; P = 0,038) fueron factores de riesgo preoperatorios independientes para la IHPH. Los niveles de ABT se correlacionaron con el ICG R15 (P = 0,001) y el flujo sanguíneo hepático efectivo (P < 0,001), que son marcadores de hipertensión portal, sin embargo, los niveles de ABT no se correlacionaron con el diámetro tumoral (P = 0,536).

ConclusionesEn comparación con el ICG R15 y la puntuación AIBL, los ABT preoperatorios factores de riesgo de IHPH en pacientes chinos con CHC, y pueden afectar el IHPH a través de su posible papel como marcador de hipertensión portal.

Hepatectomies can be curative in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but they also increase the risk for severe complications, including post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF). PHLF is a leading cause of postoperative mortality. Strategies aimed at predicting this complication include calculating the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), Child-Pugh, or albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) scores, and measuring the indocyanine green retention rate after 15 minutes of intravenous injection (ICG-R15).1 Even during a compensated cirrhosis stage, patients present varying degrees of portal hypertension, a common life-threatening complication that significantly impacts postoperative outcomes in patients with HCC.2 According to many guidelines, patients with portal hypertension are not recommended to undergo liver resection.3,4 Unfortunately, many patients with HCC in China are diagnosed as having cirrhotic liver and portal hypertension. Therefore, only a small number of patients are eligible for liver resection based on the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) framework, and many do not have the option of a curative liver resection treatment.5 Screening for patients with HCC and portal hypertension who may be suitable candidates for liver resection is crucial to improve overall survival and patient outcomes.6–9 The standard portal hypertension measurement involves calculating the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) via an invasive procedure routinely avoided in many centers.2 Although studies have shown that total bile acid (TBA) is associated with portal hypertension,10–12 it remains unclear whether TBA is also associated with PHLF in patients with HCC. Therefore, we conducted this study to identify the risk factors for PHLF.

MethodsFor this retrospective study, we recruited patients with HCC who underwent liver resection at a referral hospital from March 2019 to April 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age ≥18 years; 2) patients diagnosed as having HCC based on histopathology after liver resection; 3) Child-Pugh class A and BCLC stages A–B. The exclusion criteria were: 1) presence of other tumors; 2) patients who underwent other surgeries during the study period; 3) patients with severe failure of another organ; and 4) patients with incomplete data.

The Ethics Committee of our hospital approved the study protocol (KY-2021-11-25-1), and we conducted the study conforming to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collectionWe collected clinical data from the hospital’s electronic medical records, including age, gender, levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin, TBA, and hemoglobin, counts of white blood cells (WBC) and platelets (PLT), and the ICG R15.

DefinitionWe used the PHLF definition of the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) criteria, based on elevated levels of international normalized ratio and total bilirubin beyond the upper limits on or after the fifth day following liver resection.13

ICG R15 (%): retention rate 15 minutes after intravenous injection of indocyanine green. ICG R15 values ≤10% were considered normal and values >10% elevated.

Normal TBA levels were ≤10 µmol/L, and elevated values were >10 µmol/L.

We calculated ALBI scores using the formula: ALBI score = 0.66 × log10 (total bilirubin [mmol/L]) – 0.085 × (albumin [g/L]). ALBI values ≤−2.60 were considered grade 1, values between −2.60 and −1.39 grade 2, and values >−1.39 grade 3.7

Platelet counts <100 × 109/L were low, and counts ≥100 × 109/L were normal until the upper limit.

Statistical analysisWe expressed continuous data as medians or interquartile ranges; and we conducted Chi-square, Student’s t and Mann‒Whitney U tests for group comparisons. We also conducted univariate and multivariate analyses to identify PHLF risks. Two-tailed P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results- 1

Baseline characteristics of patients with HCC and Child Pugh class A who underwent liver resection

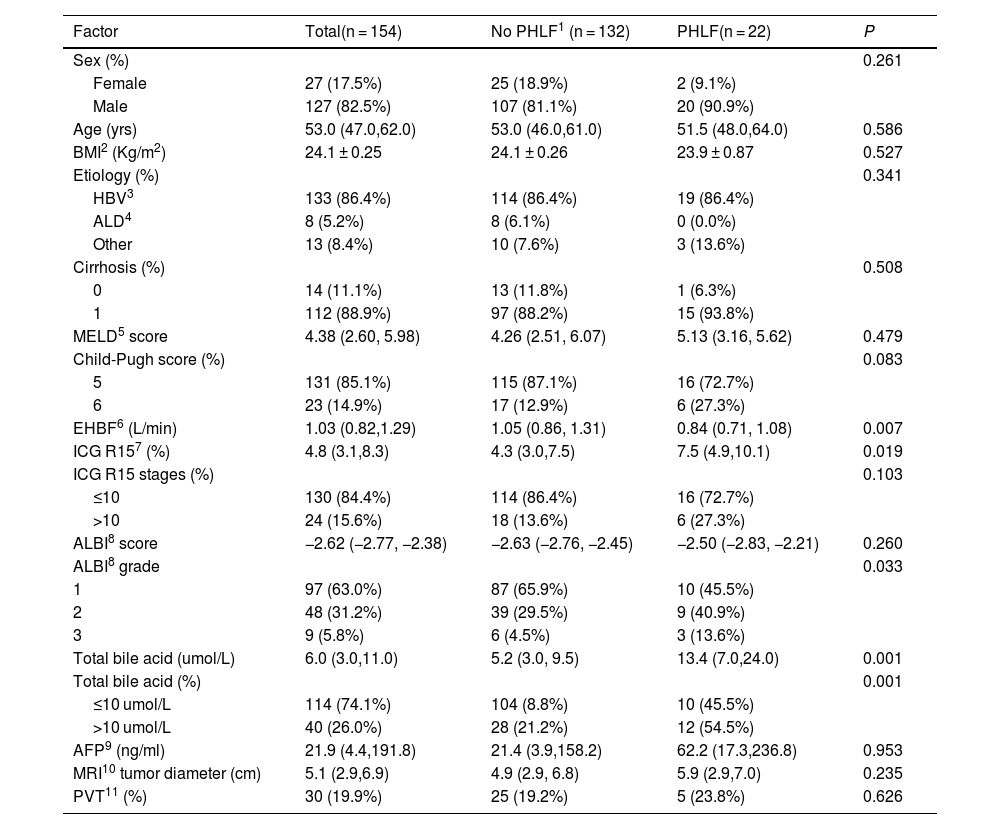

We analyzed data from 154 patients with HCC. Table 1 shows their clinical characteristics. Most patients were men (127 out of 154), with a median age of 53.0 years (47.0–62.0). Among the 154 patients with HCC, 133 (86.4%) were infected with hepatitis B virus. All patients were classified as Child Pugh A, and they underwent pathological testing after liver resection. However, we only had pathological fibrosis stage data for 126 patients, and 112 of them were diagnosed as having cirrhosis.

Baseline characteristics of HCC patients with and without PHLF.

| Factor | Total(n = 154) | No PHLF1 (n = 132) | PHLF(n = 22) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | 0.261 | |||

| Female | 27 (17.5%) | 25 (18.9%) | 2 (9.1%) | |

| Male | 127 (82.5%) | 107 (81.1%) | 20 (90.9%) | |

| Age (yrs) | 53.0 (47.0,62.0) | 53.0 (46.0,61.0) | 51.5 (48.0,64.0) | 0.586 |

| BMI2 (Kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 0.25 | 24.1 ± 0.26 | 23.9 ± 0.87 | 0.527 |

| Etiology (%) | 0.341 | |||

| HBV3 | 133 (86.4%) | 114 (86.4%) | 19 (86.4%) | |

| ALD4 | 8 (5.2%) | 8 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 13 (8.4%) | 10 (7.6%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 0.508 | |||

| 0 | 14 (11.1%) | 13 (11.8%) | 1 (6.3%) | |

| 1 | 112 (88.9%) | 97 (88.2%) | 15 (93.8%) | |

| MELD5 score | 4.38 (2.60, 5.98) | 4.26 (2.51, 6.07) | 5.13 (3.16, 5.62) | 0.479 |

| Child-Pugh score (%) | 0.083 | |||

| 5 | 131 (85.1%) | 115 (87.1%) | 16 (72.7%) | |

| 6 | 23 (14.9%) | 17 (12.9%) | 6 (27.3%) | |

| EHBF6 (L/min) | 1.03 (0.82,1.29) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.31) | 0.84 (0.71, 1.08) | 0.007 |

| ICG R157 (%) | 4.8 (3.1,8.3) | 4.3 (3.0,7.5) | 7.5 (4.9,10.1) | 0.019 |

| ICG R15 stages (%) | 0.103 | |||

| ≤10 | 130 (84.4%) | 114 (86.4%) | 16 (72.7%) | |

| >10 | 24 (15.6%) | 18 (13.6%) | 6 (27.3%) | |

| ALBI8 score | −2.62 (−2.77, −2.38) | −2.63 (−2.76, −2.45) | −2.50 (−2.83, −2.21) | 0.260 |

| ALBI8 grade | 0.033 | |||

| 1 | 97 (63.0%) | 87 (65.9%) | 10 (45.5%) | |

| 2 | 48 (31.2%) | 39 (29.5%) | 9 (40.9%) | |

| 3 | 9 (5.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Total bile acid (umol/L) | 6.0 (3.0,11.0) | 5.2 (3.0, 9.5) | 13.4 (7.0,24.0) | 0.001 |

| Total bile acid (%) | 0.001 | |||

| ≤10 umol/L | 114 (74.1%) | 104 (8.8%) | 10 (45.5%) | |

| >10 umol/L | 40 (26.0%) | 28 (21.2%) | 12 (54.5%) | |

| AFP9 (ng/ml) | 21.9 (4.4,191.8) | 21.4 (3.9,158.2) | 62.2 (17.3,236.8) | 0.953 |

| MRI10 tumor diameter (cm) | 5.1 (2.9,6.9) | 4.9 (2.9, 6.8) | 5.9 (2.9,7.0) | 0.235 |

| PVT11 (%) | 30 (19.9%) | 25 (19.2%) | 5 (23.8%) | 0.626 |

Abbreviations: PHLF: post-hepatectomy liver failure; BMI: body mass index; HBV: hepatitis B virus; ALD: alcoholic liver disease, MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; EHBF: effective hepatic blood flow; ICG R15: retention rate 15 minutes after intravenous injection of indocyanine green; ALBI score: albumin-bilirubin score; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PVT: portal vein thrombosis.

The calculated prevalence of PHLF was 14.3%. Patients with HCC had a median tumor diameter of 5.1 cm (2.9–6.9), and 47.7% had a tumor diameter greater than 5 cm according to liver images. Additionally, 26.7% of patients experienced macrovascular invasion, and 19.9% developed portal vein thrombosis, both signs of advanced disease.

- 2

Comparison of laboratory values between patients with and without PHLF

As stated, all patients had preserved liver function with Child-Pugh A chronic liver disease. Patients with and without PHLF had similar MELD and AIBL scores and tumor diameters (Table 1). However, they experienced varying degrees of portal hypertension. Patients in the PHLF group had a higher median TBA level (P = .001) and a higher median ICG R15 (P = .019). Patients with PHLF had a higher percentage of elevated TBA levels (P = .001, Fig. 1A) and a significantly higher percentage of severe AIBL grades (P = .033, Fig. 1B) than those without PHLF. However, the percentages of patients with elevated ICG R15 (P = .103, Fig. 1C), severe cirrhosis (P = .508, Fig. 1D), and high Child-Pugh scores (P = .083, Fig. 1E) were similar in both groups. In addition, the group of patients with PHLF had a higher percentage of cases with low platelet counts than the other group (P = .031, Fig. 1F).

- 3

Risk factors for PHLF in the univariate and multivariate analyses

Patients with PHLF had a significantly higher TBA.

The group of patients with PHLF had a higher percentage of cases with elevated TBA levels (P = .001, Fig. 1A) and severe albumin-bilirubin (AIBL) grades (P = .033, Fig. 1B). However, both groups had similar percentages of cases with elevated ICG R15 (P = .103, Fig. 1C), severe cirrhosis (P = .508, Fig. 1D), and high Child-Pugh score (P = .083, Fig. 1E). In addition, the group with PHLF had a higher percentage of patients with low platelet counts (P = .031, Fig. 1F).

We screened risk factors for PHLF on a univariate analysis and included all variables with P < 2.0 in the multivariate analysis. The results showed that MRI tumor diameter (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01–1.35; P = .038) and TBA level (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03–1.14; P = .003) were independent preoperative risk factors for PHLF (Table 2).

- 4

Correlations of TBA with other variables in patients with HCC

Preoperative risk factors for PHLF on univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Etiology | 0.43 | 1.13–1.37 | 0.153 | |||

| ICG R151 >10 | 2.38 | 0.82–6.87 | 0.110 | |||

| ALBI2 grades | 2.06 | 1.04–4.07 | 0.038 | |||

| EHBF3 | 0.15 | 0.03–0.70 | 0.015 | |||

| MRI4 tumor diameter | 1.11 | 0.98–1.27 | 0.113 | 1.17 | 1.01–1.34 | 0.038 |

| Albumin | 0.88 | 0.77–1.01 | 0.067 | |||

| Total bile acid > 10 umol/L | 1.10 | 1.04–1.16 | <0.001 | 3.75 | 1.35–10.42 | 0.011 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.88 | 1.07–3.33 | 0.029 | |||

Abbreviations: ICG R15: retention rate 15 minutes after intravenous injection of indocyanine green; AIBL score: albumin-bilirubin score; EHBF: effective hepatic blood flow; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

TBA levels were associated with signs of portal hypertension, and they were significantly different in patients at different stages of fibrosis (P = .026, Fig. 2A). Additionally, TBA correlated with the ICG R15 (P = .001, Fig. 2B) and effective hepatic blood flow (EHBF) (P < .001, Fig. 2C), both of which are markers of portal hypertension. However, TBA did not correlate with the tumor diameter (P = .536, Fig. 2D).

TBA was associated with signs of portal hypertension, but not with tumor size.

TBA levels differed significantly in patients with different stages of fibrosis (P = .026, Fig. 2A), and the levels correlated with ICG R15 (P = .001, Fig. 2B) and EHBF (P < .001, Fig. 2C), but not with tumor diameter (P = 0.536, Fig. 2D) in patients with HCC.

PHLF remains the leading cause of postoperative mortality.14 PHLF is a diagnosis defined by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery, including criteria that indicate impairment in the liver’s ability to function normally, such as elevated bilirubin levels and INR on or after the 5th postoperative day.13 We found that Chinese patients with HCC and preserved liver function, who had high TBA levels and large tumor sizes, were at a higher risk for PHLF than their counterparts. Many patients in China are diagnosed with advanced HCC because they do not regularly have routine medical examinations. When the patients have preserved liver function, surgery is recommended to improve their overall survival, even if they have portal hypertension.15,16 In this scenario, it is crucial to identify variables that correlate with portal hypertension in order to predict PHLF.

TBA is associated with cirrhosis, HCC, and portal hypertension. Several studies (including one with 100 cases of HCC and 100 matched control subjects) have found that elevated bile acids are associated with increased risk of HCC.12,17,18 In our study, the bias of TBA on HCC was reduced because all patients had HCC.

Some studies have revealed an association between TBA and the severity of liver disease. TBA levels have been associated with serum markers of liver injury and the NAFLD fibrosis score, as well as with the MELD score in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure.19–22 In our study, all patients had the same Child-Pugh A liver stage and normal bilirubin levels; therefore, the bias of TBA on the severity of liver disease was lower.

ICG R15 has been shown to correlate with HVPG, a gold standard test for portal hypertension.23 We found that TBA levels correlated with ICG R15 and EHBF, as well as with fibrosis stages, which are markers of portal hypertension. Thus, TBA seems to be a marker of portal hypertension. Additionally, we identified preoperative TBA levels as an independent preoperative risk factor for PHLF in patients with HCC. This suggests that TBA is a marker of portal hypertension that can impact the development of PHLF.

A study involving 1081 patients with HCC revealed that tumor size is an independent predictive factor for PHLF.24 Consistently, we found tumor size to be a risk factor for PHLF. This may be because tumor size is related to the remnant liver volume and function.

The ALBI score has been shown to provide an objective estimation of hepatic reserve and is recommended for predicting PHLF.7 In our study, the ALBI score was identified as a risk factor for PHLF on the univariate analysis. However, when compared to other factors, such as TBA level and tumor diameter on the multivariate analysis, the score was ruled out as an independent risk factor for PHLF.

Our failure to perform an HVPG invasive test to assess its association with PHLF and TBA levels is a limitation of our study. However, we reduced the biases of TBA in liver disease severity and HCC by recruiting patients with HCC and the same Child Pugh class stage, while ensuring to include patients with varying degrees of portal hypertension. Our results suggest that a high TBA level is a risk factor for PHLF. We hope that our findings will be helpful for physicians considering hepatectomy in patients with HCC.

ConclusionOur findings suggest that preoperative TBA is a risk factor for PHLF associated with portal hypertension. Thus, TBA might serve as a marker of portal hypertension in the evaluation of patients at risk for PHLF.

Credit authorship contribution statementStudy concept and design: Dali Zhang, Hui Ren; Data collection: Lixin Li, Xiaofeng Niu; Analysis of data: Xi He, Xiaofeng Zhang; manuscript writing: Xi He, Xiaofeng Zhang, and Zhijie Li; manuscript revision: Dali Zhang, Hui Ren; study supervision: Dali Zhang, Hui Ren, Zhenwen Liu. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approvalThis study protocol is in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Fifth Medical Center of Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital (KY-2021-11-25-1).

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

None.