To decide treatment of hepatic cysts diagnosis between simple hepatic cyst (SHC) and cystic mucinous neoplasm (CMN). Radiological features are not patognomonic. Some studies have suggested the utility of intracystic tumor markers.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of our prospective database including patients treated due to symptomatic SHC from 2003 to 2021. The aim of the study was to evaluate the results of treatment of symptomatic SHC and the usefulness of the determination of intracystic “carcinoembryonic antigen” (CEA) and “carbohydrate antigen” CA 19.9.

Results50 patients diagnosed and treated for symptomatic SHC were included. In 15 patients the first treatment was percutaneous drainage. In 35 patients the first treatment was laparoscopic fenestration. Four patients were diagnosed of premalignant or malignant liver cystic lesions (MCN, IPMN, lymphoma B); three of them required surgery after initial fenestration and pathological diagnosis.

Median CEA and CA 19−9 were 196 μg/L and 227.321 U/mL respectively. Patients with malignant or premalignant pathology did not have higher levels of intracystic tumor markers. Positive predictive value was 0% for both markers, and negative predictive value was 89% and 91% respectively.

ConclusionValues of intracystic tumor markers CEA and CA 19−9 do not allow distinguishing simple cysts from cystic liver neoplasms. The most effective treatment for symptomatic simple liver cysts is surgical fenestration. The pathological analysis of the wall of the cysts enables the correct diagnosis, allowing to indicate a surgical reintervention in cases of hepatic cyst neoplasia.

El tratamiento de los quistes hepáticos requiere del diagnóstico diferencial de quiste simple hepático (QSH) de la neoplasia mucinosa quística (NMQ) hepática. Las características radiológicas no son patognomónicas. Algunos estudios han sugerido la utilidad de los marcadores tumorales (MKT) intraquísticos.

MétodosAnálisis retrospectivo de base de datos prospectiva incluyendo pacientes diagnosticados de QSH sintomático desde el 2003 hasta el 2021. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar los resultados del tratamiento de los QSH sintomáticos y analizar la utilidad de la determinación de “carcinoembryonic antigen” (CEA) y “carbohydrate antigen” CA 19.9 intraquísticos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 50 pacientes tratados por quiste sintomático. En 15 pacientes el primer tratamiento fue el drenaje percutáneo. En 35 pacientes se realizó fenestración laparoscópica. Cuatro pacientes se diagnosticaron de lesiones premalignas/malignas (NMQ, NPIB, linfoma B); tres de ellos requirieron una segunda cirugía tras la fenestración y el diagnóstico anatomopatólogo.

La mediana de los valores de CEA y CA- 19.9 fue de 196 μg/L y 227.321U/mL respectivamente. Los pacientes con lesiones premalignas no tuvieron valores elevados de MKT. El valor predictivo positivo fue del 0% en ambos MKT, y el valor predictivo negativo fue de 89% y 91% respectivamente.

ConclusionesLos valores de CEA y CA 19.9 intraquísticos no permiten distinguir los QSH de las NMH. El tratamiento más resolutivo de los QSH sintomáticos es la fenestración quirúrgica. El análisis anatomopatológico de la pared del quiste posibilita su correcto diagnóstico, permitiendo indicar una reintervención quirúrgica en los casos de NMQ.

Simple hepatic cysts (SHCs) are derived from congenital exclusions of hyperplastic bile duct remnants with no communication with the bile duct. They are usually asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally, although they may occasionally cause symptoms such as abdominal pain or bloating, postprandial fullness, dyspnoea, and less common symptoms secondary to infection, perforation, or intracystic bleeding.1

With the increased use of imaging in recent years, the incidental diagnosis of cystic liver lesions has also increased.

The incidence of SHC in the general population ranges from 15%–20%. For patients with symptomatic SHC the incidence of premalignant or neoplastic lesions can be as high as 5%.2,3

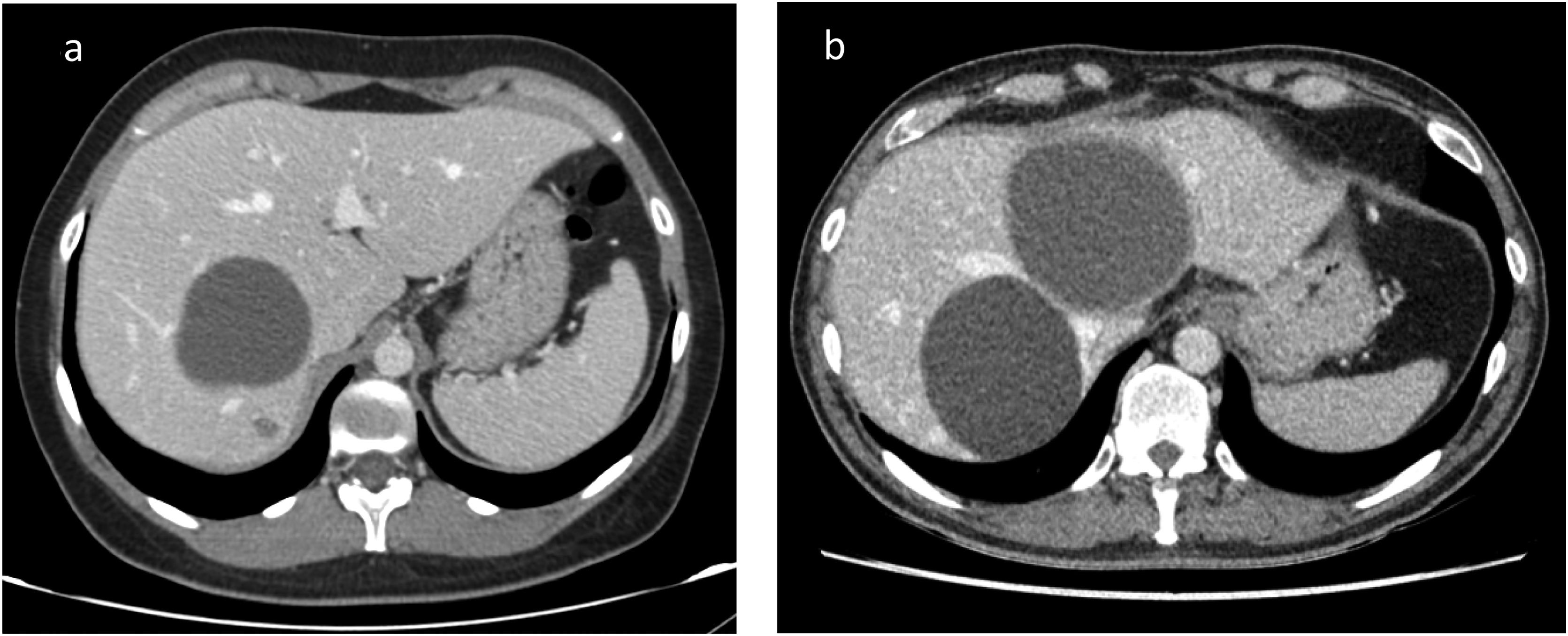

The differential diagnosis of cystic liver lesions is complex; sometimes it can be very difficult to differentiate a simple cyst from premalignant liver lesions such as cystic mucinous neoplasia (CMN) and intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB).2–4 The differential diagnosis of cystic lesions is made by imaging tests such as ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish the type of lesion by imaging alone as these types of lesions do not have pathognomonic features.5 A lack of radiological correlation may lead to unnecessary surgery.6 Therefore, further data would be interesting to enable a correct differential diagnosis.

The usefulness of tumour marker values (TM) obtained from the fluid of pancreatic cystic lesions to differentiate benign from premalignant or malignant pancreatic lesions has been demonstrated in recent years.7 Therefore, extrapolating this hypothesis to cystic liver lesions, recent attempts have been made to correlate intracystic TM values with the ability to differentiate benign cystic liver lesions from premalignant lesions.8–10 Some studies suggest that cystic lesions with elevated intracystic carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA)19.9 may be premalignant lesions while, conversely, simple cystic lesions tend to have normal TM values.9

The aim of this study is to review our experience in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of symptomatic simple cysts. Specifically, we discuss the usefulness of intracystic CEA and CA19.9 testing for the differential diagnosis between simple liver cyst and premalignant or malignant cystic liver lesions.

MethodsA retrospective analysis of our prospective database of patients treated at our centre for symptomatic SHC from January 2003 to December 2021 was performed. Patients with non-symptomatic SHC for whom no treatment was indicated are not included in the study, as they were not prospectively collected. Patients with suspected or preoperative confirmation of cystic mucinous neoplasms of the liver (CMN) were excluded, as their management would now be different.

Briefly, in cases of SCH presenting with symptoms, surgical fenestration is indicated as the first treatment of choice. In cases with non-specific symptoms, or cases of advanced age and/or comorbidity, percutaneous drainage with alcohol sclerotherapy is indicated as the first therapeutic action. In patients with clinical and radiological recurrence after drainage, the surgical option is re-evaluated, age and comorbidity permitting.

Diagnosis was based on the radiological study performed with ultrasound and/or computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging. Levels of intracystic tumour markers (CEA and CA 19.9) were determined intraoperatively or from contents obtained during percutaneous puncture. The previously described cut-off points of CEA > 30 μg/L and CA 19.9 15000 U/mL9 were considered risk criteria for CMN.

The variables studied were demographic characteristics, symptoms, imaging tests performed, treatment and progression during follow-up.

Statistical analysisData were collected in a Microsoft Office Access database and processed using SPSS. A descriptive statistical analysis of the results was performed.

ResultsFifty patients with an initial diagnosis of SHC requiring symptom-specific treatment were included. Most patients were female (70%), with a median age of 64 years, and with a median Charlson index of 5.

The most common symptom was abdominal pain (35/50; 70%), followed by oral intolerance and postprandial fullness (2/50; 4%), other less frequent symptoms such as infection and jaundice occurred in only one patient, respectively. Symptoms were non-specific in 18% of patients.

Regarding cyst characteristics, the most frequent was the single cyst in 46%, 24% of patients had fewer than 5 cysts, while 30% had more than 5 cysts. The median size was 13 cm [2–22] and the most common cyst type was simple cyst in 60%, complex in 24% (12/50). Median follow-up was 36 months [11–144].

Diagnostic tests performed were ultrasound (83%), CT (88%), MRI (55%), and cytology for pathology (81%). Intracystic tumour markers were detected in 41 patients (77%).

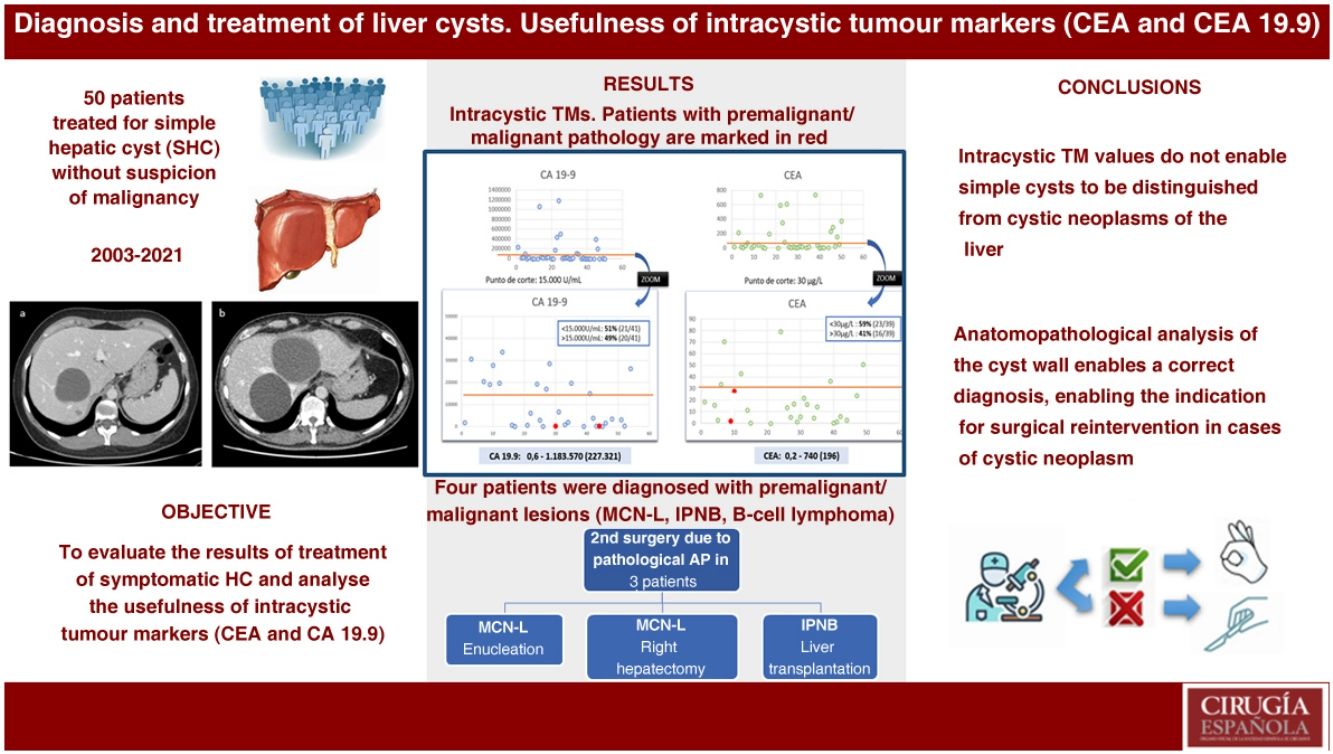

Intracystic TM values showed great variability (Fig. 1). The median CA 19.9 was 227,321 U/mL [.6–1183570], while the median CEA was 196 μg/L [0.2–740]. The TM values of the patients with pathological anatomy other than simple cyst, we only had values from two of the four patients, are marked in red in Fig. 1. The patient with a diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma had a CEA of 1.8 μg/L and CA 19.9 of 222 U/mL. One of the patients with pathological anatomy of CMN had a CEA of 27.8 μg/L and CA 19.9 of 224 U/mL.

Fifty-one percent of the patients with SHC tested for CA 19.9 above the cut-off point of 15000 U/mL and 59% had CEA above 30 μg00/L. This reflects a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0% for both TMs and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 89% and 91% respectively.

All 50 patients studied in our series underwent treatment for symptom onset (Fig. 2). Conservative treatment with drainage and percutaneous sclerotherapy was indicated in 15 patients and was effective in only three. Of the patients in whom it was not effective (12/15), surgery was indicated as a second treatment in three, a watchful waiting approach was decided in one patient due to few symptoms, and eight patients underwent a second drainage and sclerotherapy. The four patients whose symptoms persisted underwent surgery, which was effective as a third treatment, and two patients required a third drainage without resolution, therefore, one patient underwent successful surgery, and a watchful waiting approach was decided in the second patient due to comorbidities.

Surgical fenestration was indicated as the first treatment in 35 patients, and was successful in most of them (29/35; 82.8%). Of the six patients in whom surgery failed, one patient required percutaneous drainage due to recurrence of symptoms and in two patients watchful waiting was decided due to improvement of symptoms. In three patients a second surgery was indicated because of the pathological anatomy of the cyst wall. Given the clinical course, none of the patients with sclerotherapy who did not undergo surgery were considered to have a cystic neoplasm.

In three patients, a second surgery was indicated due to pathological diagnosis of the cyst wall; in two patients the diagnosis was of CMN and therefore enucleation was indicated in one patient and a right hepatectomy in the second, these procedures were indicated according to the location of the lesions (Fig. 3). A third patient required a liver transplant due to a diagnosis of IPNB and multifocal involvement, and vascular contacts. All three patients progressed well without complications in the postoperative period or during follow-up. The remaining anatomopathological findings reported simple cyst in 40 cases and one patient was diagnosed with lymphoma. The latter patient was evaluated by the haematology service; she was diagnosed with fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma, an entity with a good prognosis and, as it was a chance finding, she did not require any treatment, just continued monitoring.

DiscussionThe diagnosis and management of cystic liver lesions is established in different clinical guidelines.1,2 Treatment is indicated if symptoms are present or if malignancy is suspected. However, the differential diagnosis between simple liver cyst and premalignant or malignant hepatic cystic lesion (CMN or IPNB) is complex. Recently, there have been reports of over-diagnosis of suspected CMN, leading to unnecessary surgery.6 A correct preoperative diagnosis is necessary for the correct therapeutic indication.

Once a diagnosis of symptomatic SHC has been confirmed, treatment will be tailored to the patient's characteristics. Drainage or aspiration of the cyst is generally not recommended due to the high recurrence rate. The recommended treatment of choice is surgery whenever possible. If there is no suspicion of malignancy and surgery is only indicated due to symptoms, laparoscopic fenestration is indicated. However, if surgery is indicated due to suspicion of malignancy, complete excision of the cyst is recommended.1,2 For complete excision, enucleation is indicated whenever possible; in some cases, hepatectomy or even liver transplantation may be necessary.1

However, it is not always easy to indicate the correct treatment, because given the non-specific symptoms in these patients it may be difficult to indicate surgical treatment without being able to offer certainty of symptom remission. Therefore, in our centre recommended initial treatment is surgical fenestration in young, operable patients with specific symptoms related to the liver cyst. On the other hand, in older patients with comorbidities or if there are doubts that the cysts are really symptomatic, percutaneous treatment with drainage or sclerotherapy is decided.

Radiological techniques cannot conclusively differentiate between a simple cyst and a premalignant cystic lesion.1,5 The anatomopathological study of the cyst wall after fenestration enables a correct diagnosis, which would indicate surgical reintervention in cases of hepatic cystic neoplasia. However, a test that allows the diagnosis to be accurately established preoperatively would be of great interest. With this aim of improving radiological reliability, algorithms have recently been developed that can improve diagnostic reliability.11 Another line of study is the determination of intracystic TMs.

From a pathological and immunohistochemical perspective, premalignant pancreatic and hepatic cystic lesions have many common features.12 While in the management of pancreatic cystic lesions testing for intracystic CEA has a role in the differential diagnosis, its usefulness in the management of hepatic cystic lesions has not been clearly established. Fuks et al.10 studied this relationship with a sample size of 118 patients, including simple cysts and hepatic cystic tumours. No significant differences were found for Ca19.9 and CEA TMs, however, they defined cut-off points above which suspicion of malignant cystic mucinous lesions could be increased with very low sensitivity and specificity.

Considering the cut-off point proposed by Fuks et al.10 we observed that up to 60% of the patients in our series with SHC had CA 19.9 above the reference value, and 54% exceeded the reference value as pathological CEA. When reviewing patients with elevated TMs (CA 19.9 > 250000 μg/L and CEA > 300 U/mL) we confirmed that the pathological anatomy was diagnostic of SHC in all of them. In contrast, the MKT values of the two patients with premalignant lesions were below the established cut-off values. Thus, in our experience TM testing does not seem to be useful in the differential diagnosis of cystic liver lesions.

A third tumour marker has been described that is associated with different types of tumours, namely tumour associated glycoprotein 72 (TAG72). Ouyang et al.13 studied TAG72 as a prognostic factor in relation to gallbladder neoplasia, concluding that TAG72 is not present in normal biliary cells and that the presence of this TM in patients with gallbladder tumours may be a clinicopathological criterion of aggressiveness. Following these findings, Fuks et al.10 studied the relationship between TAG72 and cystic lesions of the liver and concluded that most patients with mucinous cysts expressed elevated TAG72 (26/27) compared to patients with simple cysts (12/75). Thus, it seems that this marker could be useful. However, in our case it could not be analysed as it is not possible to test for it in our centre

Assessing the results of the treatments performed in our series, we agree with that described previously, because the most effective treatment in our experience was surgery, with an efficacy rate of up to 87%, compared to 23% for simple drainage or sclerotherapy.

The review of our experience shows the low efficacy of percutaneous drainage and sclerotherapy.4 The most effective treatment for symptomatic simple hepatic cysts is laparoscopic fenestration with low morbidity and mortality and recurrence. Given the high recurrence rate, we believe that drainage with sclerotherapy should be reserved for improving symptoms in patients who are not optimal for surgery.14

Our work offers a description of the diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic simple cysts. However, it has a number of limitations, firstly, the limited number of cases, especially considering the low frequency of CMN. The selection of symptomatic SHC may be a selection bias; however, we focused on these cases as this is the most frequent clinical scenario. As the study is a retrospective analysis of a prospective database, not all patients were studied equally, and tumour marker testing is not available in all cases. The loss of long-term follow-up is another limitation to be considered. Finally, as mentioned above, although TAG72 seems to be a useful marker, we cannot test for it in our centre.

However, the scarcity of published literature is noteworthy, and therefore this study may be useful to provide more information on the management of cystic liver disease in our setting and constitute a first step for future studies. Future studies should perhaps be based on the search for new intracystic markers.

In conclusion, intracystic CEA and CA 19−9 tumour marker values do not enable us to distinguish simple cysts from hepatic cystic neoplasms due to their null positive predictive value.

The diagnosis of cystic lesions, especially if there is suspicion of malignancy, should not be based solely on one diagnostic test but on a combination of them, and the review of individual cases in a multidisciplinary committee.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.