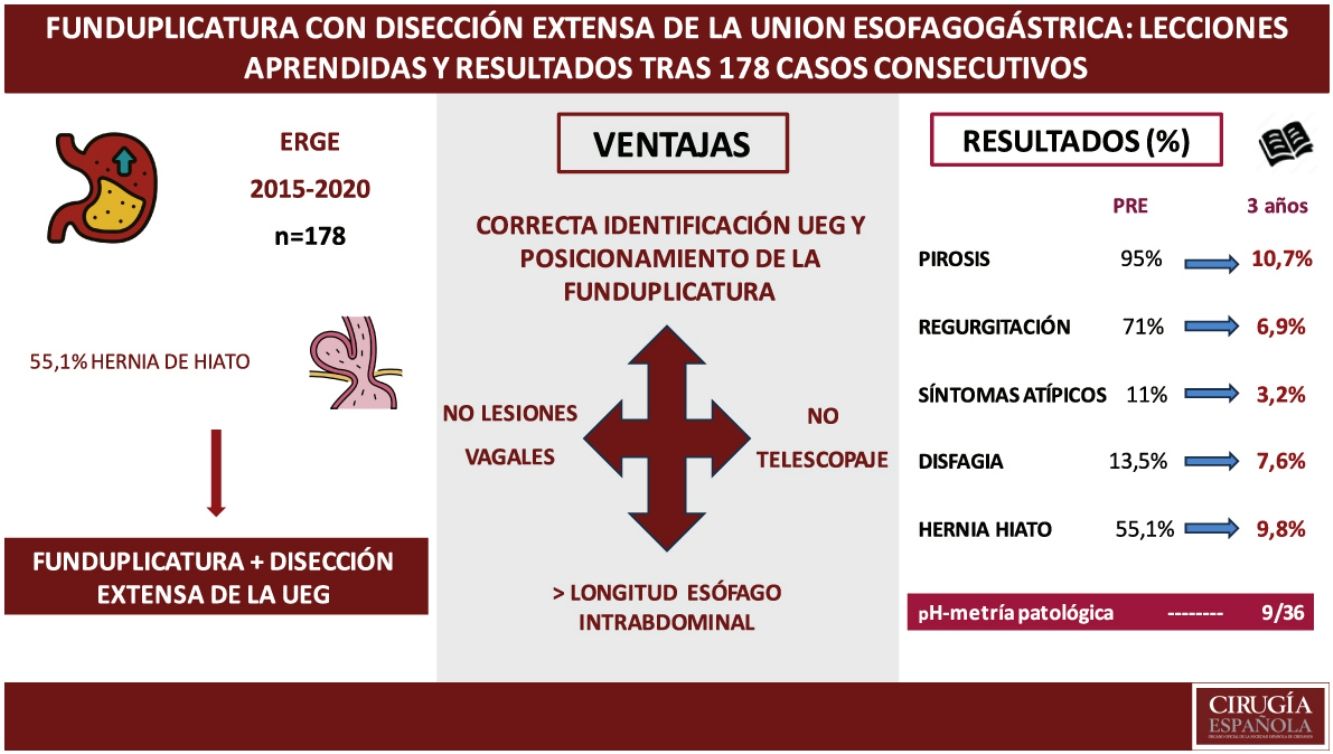

Antireflux surgery is commonly associated with significant recurrence and complication rates, and several surgical techniques have been proposed to minimize them. The aim of this study is to evaluate the results of a fundoplication with extensive dissection of the esophagogastric junction 1 and 3 years after the procedure.

MethodsRetrospective observational study including 178 patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease or hiatal hernia who underwent fundoplication with extensive dissection of the esophagogastric junction between 2015 and 2020. Hernia recurrence, symptoms and quality of life at 1 and 3 years after surgery were assessed by barium transit, endoscopy and questionnaires for symptoms and quality of life (GERD-HRQL).

ResultsHeartburn rate was 7.5% and 10.7% at 1 and 3 years respectively, regurgitation 3.8% and 6.9% and dysphagia was 3.7% and 7.6%. The presence of hiatal hernia was evident preoperatively in 55.1% and in 7.8% and 9.6% at follow-up and the median GERD-HRQL scale was 27, 2 and 0 respectively. There were no cases of slippage of the fundoplication or symptoms suggestive of vagal injury. No differences were found when comparing the different types of fundoplication in terms of reflux and recurrence or complications.

ConclusionsFundoplication with extensive dissection of the esophagogastric junction contributes to correct positioning and better anchorage of the fundoplication, which is associated with low rates of hiatal hernia and reflux recurrence, as well as absence of slippage and lower possibility of vagal injury.

La cirugía antirreflujo, se asocia con frecuencia a tasas significativas de recurrencia y complicaciones habiéndose propuesto varias técnicas quirúrgicas para minimizarlas. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar los resultados a 3 años de una funduplicatura con disección extensa de la unión esofagogástrica.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo que incluyó a 178 pacientes con enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico o hernia de hiato a los que se les realizó una funduplicatura con disección extensa de la unión esofagogástrica entre 2015 y 2020. La recidiva herniaria, los síntomas y la calidad de vida al año y 3 años de la cirugía fueron evaluados mediante tránsito baritado, endoscopia y cuestionarios para síntomas y calidad de vida (GERD-HRQL).

ResultadosLa tasa de pirosis fue de 7,5% y 10,7% al año y 3 años respectivamente, regurgitación 3,8% y 6,9% y disfagia fue 3,7% y 7,6%. La presencia de hernia hiatal se evidenció preoperatoriamente en el 55,1% y en el 7,8% y 9,6% en el seguimiento y la mediana de la escala GERD-HRQL fue 27, 2 y 0 repectivamente. No aparecieron casos de telescopaje de la funduplicatura ni síntomas que sugieran lesión vagal. No se encontraron diferencias al comparar los distintos tipos de funduplicatura en términos de recidiva del reflujo, complicaciones o recurrencia de la hernia.

ConclusionesLa funduplicatura con disección extensa de la unión esofagogástrica contribuye a su correcto posicionamiento y mejor anclaje, lo que asocia bajas tasas de recidiva herniaria y del reflujo, así como disminuye la posibilidad de telescopaje y lesión vagal.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is one of the most common health problems with prevalence rates in Europe from 8.8% to 25.9%.1 Typical symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation,2 although it may also present with abdominal or chest pain, dysphagia,3 or extra-oesophageal manifestations such as cough, or chronic pharyngitis. It may play a role in asthma exacerbations,4 onset of anaemia, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding.5

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the mainstay of medical treatment,6 although a high percentage of patients with heartburn7 and regurgitation8 fail to respond to them. Surgery is the only effective treatment for PPI failure.9,10

Since Rudolph Nissen11 performed the first fundoplication in 1937, many alternatives to the technique have been proposed to control GORD symptoms and minimise procedural complications.12

In 1988, Rossetti described a variant technique to treat patients with GORD and associated gastroduodenal ulcer or severe oesophagitis, in which he dissected the OGJ and performed a selective proximal vagotomy associated with fundoplication.13 One year later, he added a modification by placing the fundoplication between the OGJ and the proximal part of the lesser gastric curvature and the vagal trunks to improve its anchorage and reduce the risk of slippage.14

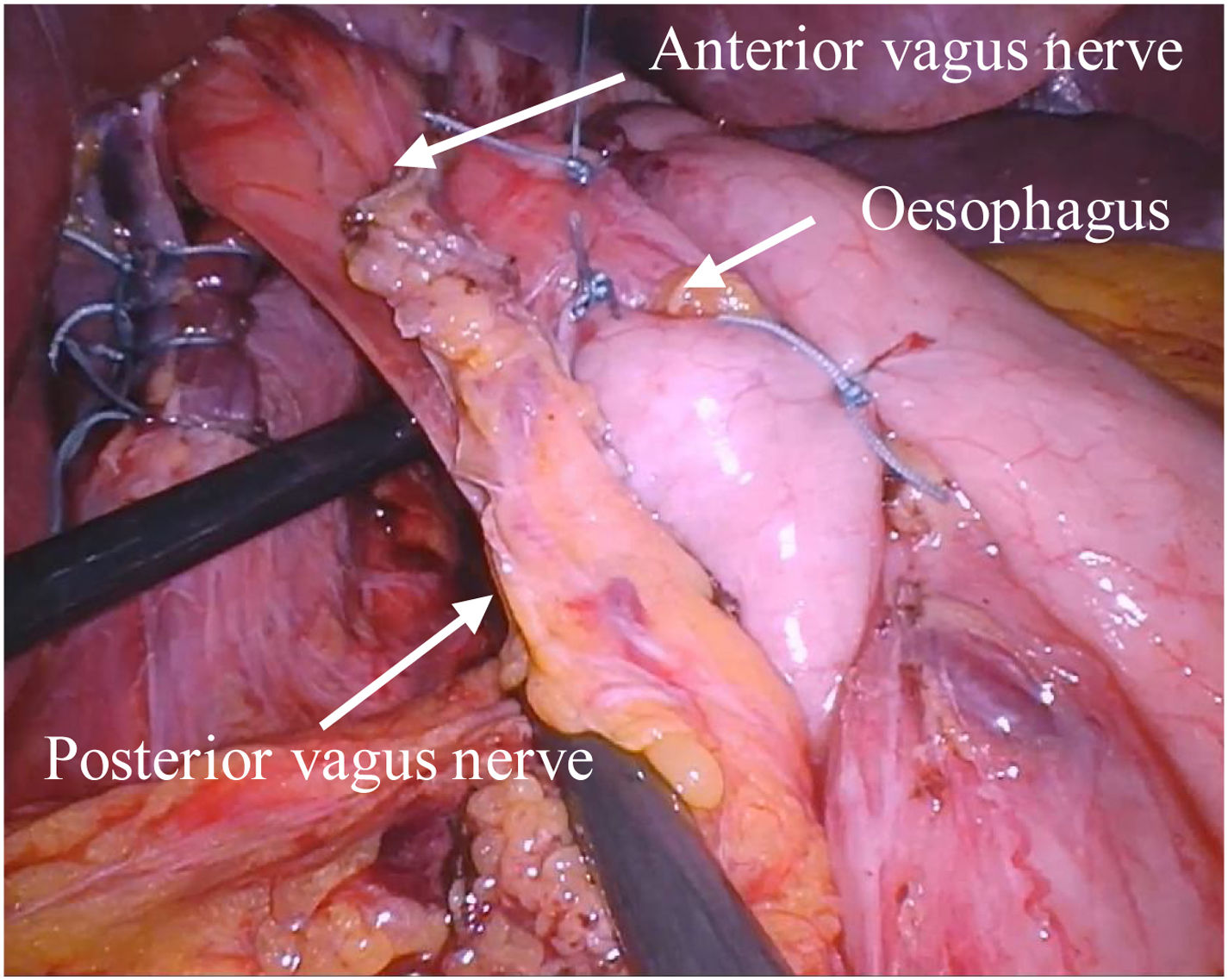

Given the lack of information in the literature on the medium and long-term outcomes of this technical modification, in our unit we routinely perform extensive dissection of the OGJ prior to creating a fundoplication anchored between the vagal trunks and the distal oesophagus. This can offer a number of advantages: gaining additional intra-abdominal oesophagus length, avoiding malpositioning of the valves, decreased occurrence, or recurrence of hiatus hernia (HH) by preventing the fundus slipping over the fundoplication (telescoping), and identifying and preserving the vagus nerve.

The aim of this study was to evaluate clinical outcomes, hernia recurrence, quality of life, and satisfaction at 1 and 3 years in patients undergoing fundoplication with extensive dissection of the oesophagogastric junction.

MethodsPatients and surgical techniqueAll patients undergoing surgery between 2015 and 2020 with a confirmed diagnosis of symptomatic GORD with or without hiatal hernia, patients with symptomatic hiatal hernia types I–IV who underwent fundoplication as an antireflux procedure, and those revision surgeries in which fundoplication was included as part of the procedure were included.

The exclusion criteria were patients under 18 years of age, patients with previous gastric resections, patients with 2 or more previous antireflux surgeries, or surgeries that required conversion to open approach.

The institution’s ethics committee approved the study.

Surgical techniqueWe did not use nasogastric tube, calibrated probes, or urinary catheter during the surgery.

Extensive dissection of the OGJ begins in the proximal third of the lesser curvature. The fat pad is dissected and retracted posteriorly and both vagal trunks are identified and lateralised Fig. 1.

The short vessels are sectioned and then a hiatorrhaphy is performed with non-absorbable discontinuous sutures.

Finally, in patients with severe motor impairment, a partial 270° Toupet fundoplication was performed. In those with preserved motility, a modified fundoplication was created consisting of anterior fixation of both valves with a stitch over the distal oesophagus and the OGJ and suture of each valve to the anterolateral aspect of the oesophagus. This modification described by Luketich,15 which we will hereafter refer to as 320° fundoplication, is intended to minimise the risk of dysphagia associated with full 360° fundoplication, while maintaining correct reflux control Fig. 2.

Preoperative assessment and follow-upAt baseline, we undertook a clinical assessment, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE), oesophago-gastric-duodenal transit (OGDT) and oesophageal functional study with manometry, and 24-h pH monitoring. A clinical re-assessment and OGDT were then performed one month after surgery, and a further clinical re-evaluation, UGE, OGDT, and functional study one year and three years after surgery for those patients with clinical suspicion of recurrence. Postoperative complications were collected and classified according to Clavien-Dindo grade.16 Surgical reinterventions and unscheduled 30- and 90-day readmissions were also documented.

Symptom assessmentPatients were followed up by 3 senior surgeons from the oesophagogastric surgery unit by face-to-face or telephone interview in which postoperative symptoms, PPI intake, and quality of life were assessed using the GERD-HRQL scale described by Velanovich17 which includes 10 questions about heartburn, dysphagia, or medication intake with a score between 0 and 45.

Typical, atypical, and other symptoms such as dyspnoea or abdominal pain were assessed as quantitative dichotomous variables.

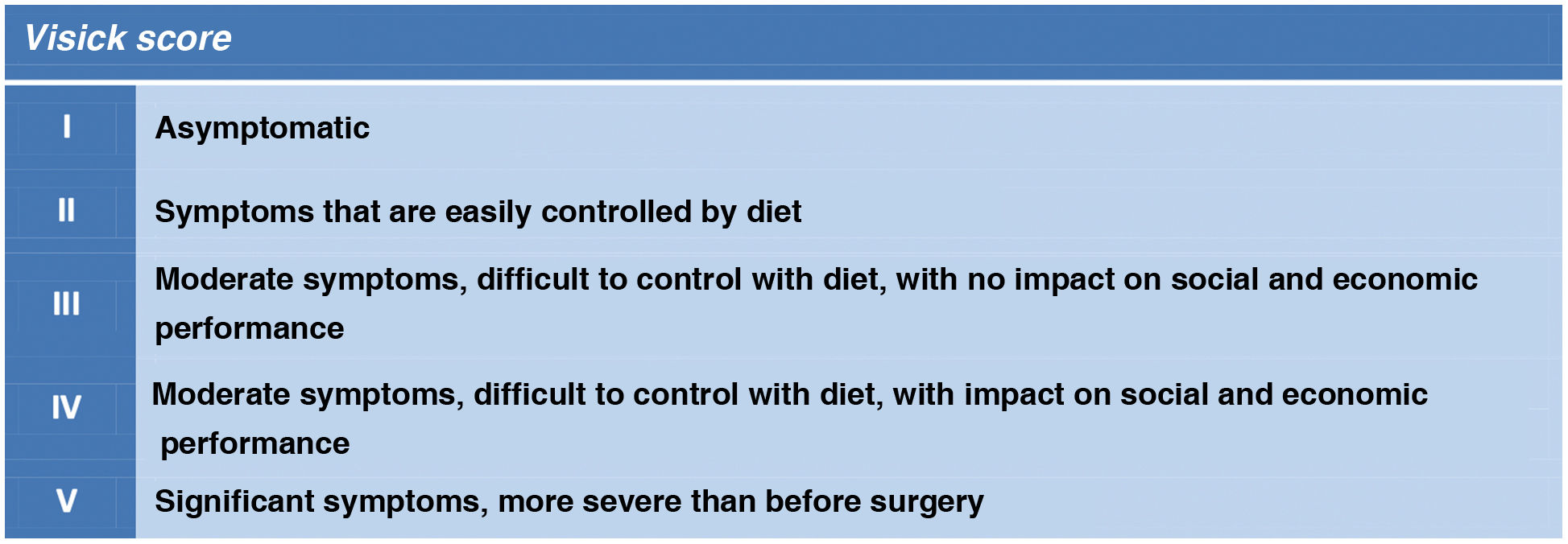

Dysphagia was classified using the Visick score18 as 1) mild (Visick grade II), 2) moderate (Visick III) and 3) severe (Visick IV and V) Fig. 3.

Endoscopy and radiological studyUGE and TEGD were performed preoperatively and during follow-up to study for oesophagitis, Barrett's oesophagus, and the presence or recurrence of HH.

The Los Angeles classification19 and the Prague criteria20 respectively were used to assess oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus. Biopsies in Barrett's oesophagus were taken according to the Seattle protocol.21

Two members of the radiology service performed radiological evaluation. Recurrence of HH was defined as the gastric chamber ascending above the level of the diaphragm.

Functional studyThe presence of pathological reflux was defined as a score >14.72 on the scale described by DeMeester.22 Conventional manometry was performed in 2015–2016 and high-resolution manometry (HRM) between 2017–2020, to detect oesophageal motility disorders.

Patients with severe motility disorders, defined as such by the manometry report or with a distal contractile integral<450 on HRM, underwent partial Toupet 270 ° fundoplication.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as percentages and quantitative variables as mean values with standard deviation (SD) in the case of normal distribution, median with interquartile range (IQR) being used for the quality of life variable. Qualitative variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test with continuity correction or Fisher's exact test when at least 25% of the values showed an expected frequency of less than 5.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 17.0. A significance level of 5% was assumed (p < .05).

ResultsA total of 229 patients underwent antireflux surgery at our centre between October 2015 and December 2020. Of these, 178 (77.7%) underwent fundoplication with extensive OGJ dissection. All cases were performed laparoscopically.

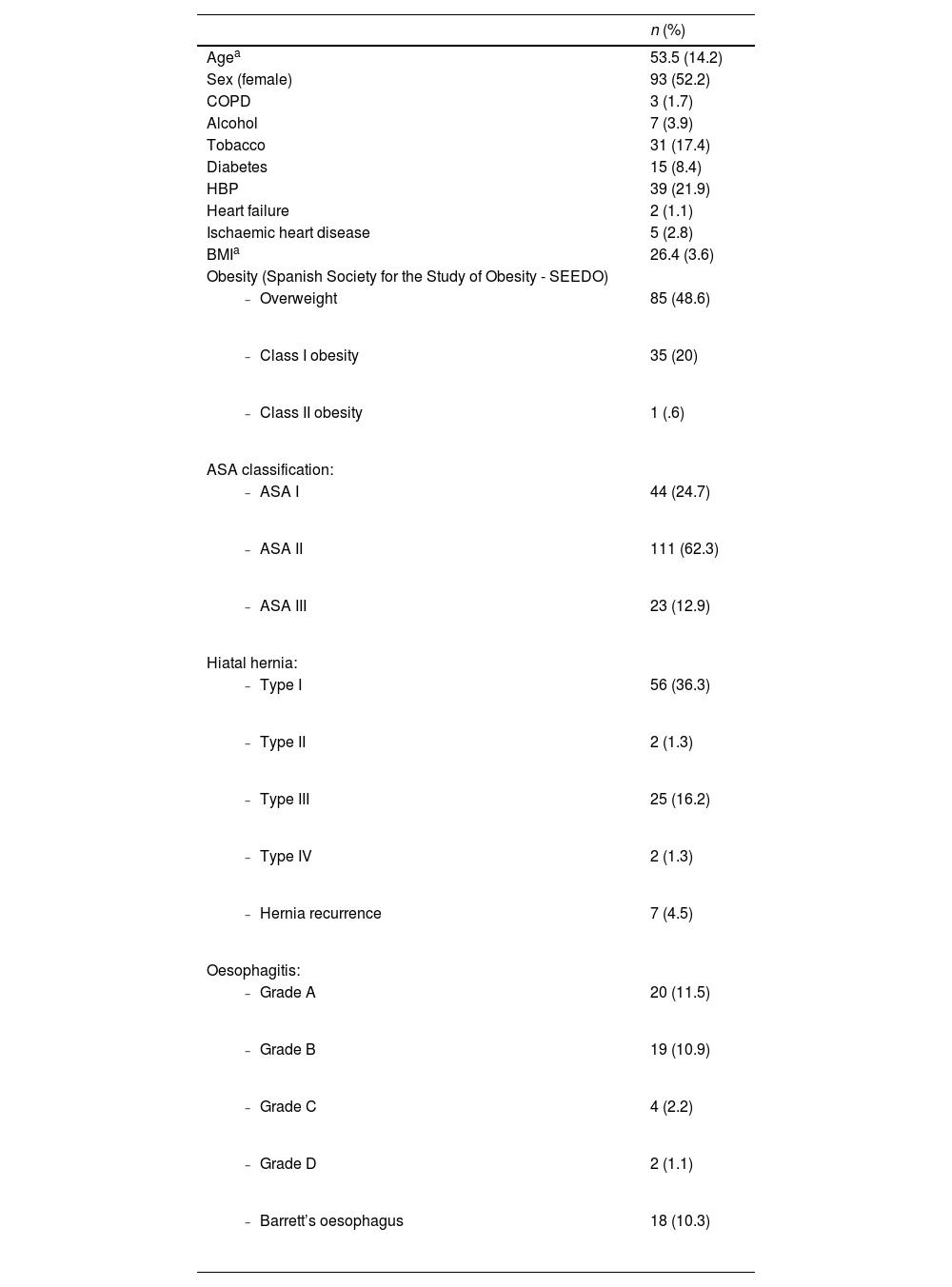

The mean age of the patients was 53.3 years, 52.2% were women. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1

Demographic characteristics of the patients.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Agea | 53.5 (14.2) |

| Sex (female) | 93 (52.2) |

| COPD | 3 (1.7) |

| Alcohol | 7 (3.9) |

| Tobacco | 31 (17.4) |

| Diabetes | 15 (8.4) |

| HBP | 39 (21.9) |

| Heart failure | 2 (1.1) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5 (2.8) |

| BMIa | 26.4 (3.6) |

| Obesity (Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity - SEEDO) | |

| 85 (48.6) |

| 35 (20) |

| 1 (.6) |

| ASA classification: | |

| 44 (24.7) |

| 111 (62.3) |

| 23 (12.9) |

| Hiatal hernia: | |

| 56 (36.3) |

| 2 (1.3) |

| 25 (16.2) |

| 2 (1.3) |

| 7 (4.5) |

| Oesophagitis: | |

| 20 (11.5) |

| 19 (10.9) |

| 4 (2.2) |

| 2 (1.1) |

| 18 (10.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI (Body mass index), COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), HBP (High blood pressure).

Seven patients had previously undergone anti-reflux surgery and there was telescoping of the fundoplication in 4.

At the time of diagnosis, 166 patients (93.3%) had heartburn, 127 (71.3%) regurgitation and 24 (13.5%) dysphagia, 16 mild (Visick II), 5 moderate (Visick III), and 3 severe (Visick IV-V). Twenty-two (12.4%) reported laryngitis and 12 (6.7%) dyspnoea secondary to a large HH.

The median (IQR) preoperative GERD-HRQL quality of life score was 27(15).

All patients were taking PPIs: 48% were non-responders and 39.3% had a partial response.

pH-monitoring was pathological in 156 patients (87.6%). Oesophageal manometry revealed moderate or severe motility disorder in 36% of cases.

Preoperative OGDT was performed in 154 patients, showing HH in 85 (55.1%), the most frequent being type I in 56 (36.6%). Table 1.

One hundred and seventy-four UGEs were performed (97.7%). Twenty patients (11.5 %) had grade A oesophagitis as the most frequent disorder, Barrett's oesophagus in 18 cases (10.1 %). Two patients had low-grade dysplasia (LGD).

The most frequent technique was the Toupet fundoplication in 105 cases (58.9%) followed by the 320° fundoplication (73 cases, 41,1%).

During the postoperative period, 6 patients (3.3%) presented medical complications, the most frequent being respiratory in 3 cases (1.8%, Clavien-Dindo I and II) and cardiovascular in 2 cases (1.2%, Clavien-Dindo II).

Seven (3.9%) patients presented surgical complications, the most common being haemorrhage in 2 cases (1.2%, Clavien-Dindo II) and surgical site infection in 2 cases (1.2%, Clavien-Dindo I).

One patient presented with evisceration requiring surgery during admission (Clavien-Dindo IIIb).

There was 1 readmission at 30 days for acute volvulus requiring urgent reoperation at another centre (Clavien-Dindo IVa).

No other 90-day readmissions were recorded.

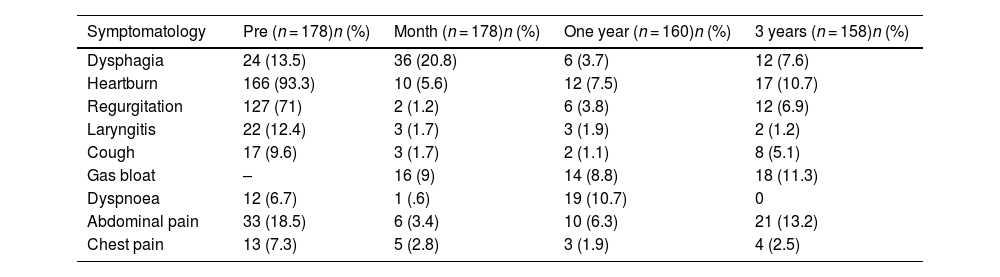

Follow-up one year after surgeryOne hundred and sixty patients (89%) were followed up. Ten (7.5%) presented with heartburn, 6(3.7%) with regurgitation, and 3(1.9%) with laryngitis.) Six (3.7%) reported dysphagia, 5 mild (Visick II), and 1 moderate (Visick III). Fourteen (8.8%) had symptoms related to gas-bloat syndrome. Table 2

Symptoms presented preoperatively, at 1 month, at one year, and at 3 months of follow-up.

| Symptomatology | Pre (n = 178)n (%) | Month (n = 178)n (%) | One year (n = 160)n (%) | 3 years (n = 158)n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysphagia | 24 (13.5) | 36 (20.8) | 6 (3.7) | 12 (7.6) |

| Heartburn | 166 (93.3) | 10 (5.6) | 12 (7.5) | 17 (10.7) |

| Regurgitation | 127 (71) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (3.8) | 12 (6.9) |

| Laryngitis | 22 (12.4) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) |

| Cough | 17 (9.6) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 8 (5.1) |

| Gas bloat | – | 16 (9) | 14 (8.8) | 18 (11.3) |

| Dyspnoea | 12 (6.7) | 1 (.6) | 19 (10.7) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 33 (18.5) | 6 (3.4) | 10 (6.3) | 21 (13.2) |

| Chest pain | 13 (7.3) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) |

Forty-one patients underwent pH-monitoring (25.6%), which was pathological in 6: 16.2% remained on treatment with PPIs.

Forty patients (25%) underwent UGE. Oesophagitis disappeared in 84.6% of cases and metaplasia in 16.6%. One patient developed de novo LGD which remitted at 3-month follow-up after intensive treatment with PPIs.

OGDT was performed in 153 (85.6%) patients showing hernia recurrence in 12 (7.8%).

The median (IQR) of the GERD-HRQL quality of life scale was 2(5).

Follow-up at 3 yearsOne hundred and fifty-eight patients (88.7%) were evaluated. Seventeen (10.7%) reported heartburn, 12(7.6%) regurgitation, and 2(1.2%) laryngitis. Thirty-four patients (21.5%) underwent 24-hr pH monitoring, which was pathological in 9.

Twelve (7.6%) had dysphagia; 2 had moderate dysphagia (Visick III) and 1 severe dysphagia (Visick IV-V), requiring endoscopic dilatation with good clinical outcome.

Forty-nine UGEs were performed (31%). Oesophagitis disappeared in 85.7% and 83.4% maintained metaplasia. No cases showed dysplasia. No de novo oesophagitis was recorded.

Twenty-two point seven percent remained on treatment with PPIs.

A total of 142 (89.8%) OGDTs were performed, revealing HH in 14 (9.8%).

The median (IQR) GERD-HRQL quality of life score was 0 (2).

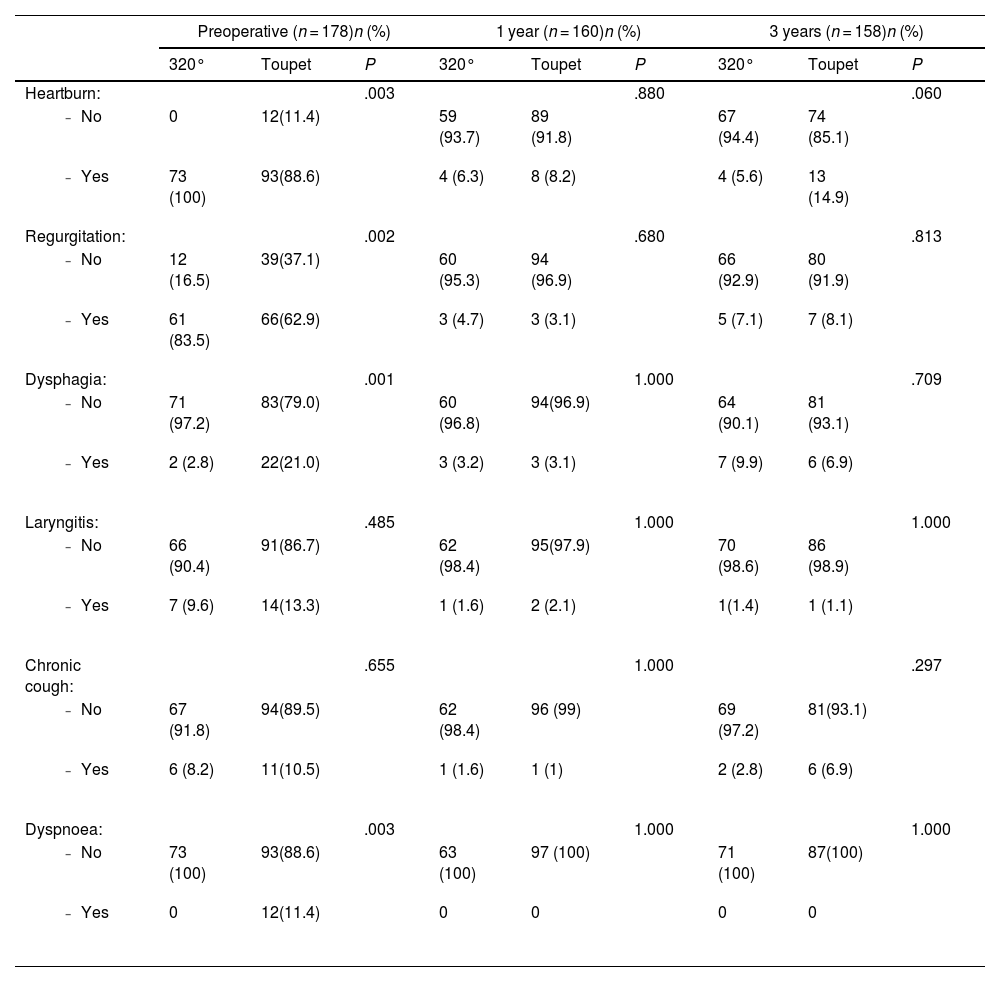

Results according to fundoplication typeIn our study, there is a clinically relevant difference, without reaching statistical significance, in the higher occurrence of heartburn at 3 years in those patients who underwent partial fundoplication (5.6% vs 14.9%; p = .060). Table 3

Symptomatology according to type of fundoplication.

| Preoperative (n = 178)n (%) | 1 year (n = 160)n (%) | 3 years (n = 158)n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320° | Toupet | P | 320° | Toupet | P | 320° | Toupet | P | |

| Heartburn: | .003 | .880 | .060 | ||||||

| 0 | 12(11.4) | 59 (93.7) | 89 (91.8) | 67 (94.4) | 74 (85.1) | |||

| 73 (100) | 93(88.6) | 4 (6.3) | 8 (8.2) | 4 (5.6) | 13 (14.9) | |||

| Regurgitation: | .002 | .680 | .813 | ||||||

| 12 (16.5) | 39(37.1) | 60 (95.3) | 94 (96.9) | 66 (92.9) | 80 (91.9) | |||

| 61 (83.5) | 66(62.9) | 3 (4.7) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (7.1) | 7 (8.1) | |||

| Dysphagia: | .001 | 1.000 | .709 | ||||||

| 71 (97.2) | 83(79.0) | 60 (96.8) | 94(96.9) | 64 (90.1) | 81 (93.1) | |||

| 2 (2.8) | 22(21.0) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (9.9) | 6 (6.9) | |||

| Laryngitis: | .485 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 66 (90.4) | 91(86.7) | 62 (98.4) | 95(97.9) | 70 (98.6) | 86 (98.9) | |||

| 7 (9.6) | 14(13.3) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2.1) | 1(1.4) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Chronic cough: | .655 | 1.000 | .297 | ||||||

| 67 (91.8) | 94(89.5) | 62 (98.4) | 96 (99) | 69 (97.2) | 81(93.1) | |||

| 6 (8.2) | 11(10.5) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (6.9) | |||

| Dyspnoea: | .003 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 73 (100) | 93(88.6) | 63 (100) | 97 (100) | 71 (100) | 87(100) | |||

| 0 | 12(11.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

No statistically significant difference was found in response to PPIs, quality of life study, or recurrence of HH.

DiscussionBy correctly locating the OGJ and anchoring the valves as facilitated by fundoplication with extensive dissection of the OGJ, at 3-year follow up we obtained rates of heartburn of around 10%, regurgitation of 7.6%, and atypical symptoms of less than 5%, while maintaining dysphagia rates of around 7%. The recurrence rate of hiatal hernia was 9.8% and in more than 80% of cases the previous oesophagitis disappeared, all of which improved the quality of life of the patients, as evidenced by a decrease in the median GERD-HRQL score from 27 to 0. We found no statistically significant differences comparing the different fundoplication types.

Correct fundoplication positioning has contributed to low clinical reflux recurrence rates. Dallemagne et al,23 report reflux control success rates of 93% after Nissen fundoplication and 82% after Toupet fundoplication. Along the same lines, Luketich et al24 report, at 18 months follow-up, persistent heartburn in 23% and 27.6% and regurgitation in 8.8% and 10% of patients undergoing Nissen and Toupet fundoplication, respectively.

However, several series25 report resolution rates of atypical symptomatology after antireflux surgery of less than 50%.

The form of fundoplication with the valves anchored between the vagal trunks and the oesophagus probably contributed to the low hiatal hernia rate at 3-year follow-up.

The high rates of hernia recurrence described in the literature remain poorly understood, varying between 5% and 59%,26–29and remain one of the unsolved problems of this pathology.

No patient in our study had telescoping or malpositioning of the fundoplication during follow-up.

Horgan et al30 describe up to 16% of patients with telescoping (hernia type Ib of the classification of anatomical failure) and 6.4% of patients with malpositioning (hernia type III). Pennanthur et al31 reported malpositioning of the wrap over the gastric body in 13.8% of cases in a series of 80 revision surgeries.

No symptoms related to vagal damage, such as chronic diarrhoea with no other apparent cause or clinical symptoms due to delayed gastric emptying, were observed during follow-up.

Lindeboom et al32 report vagus nerve damage in up to 10%, although not always associated with delayed gastric emptying. Van Rijn et al33 similarly observed iatrogenic vagus nerve damage in 20% of a series of 125 patients, with a significant delay in postoperative gastric emptying in the vagal injury group.

Limitations of the study include firstly that reflux recurrence was assessed on the basis of clinical outcomes, and functional control tests were only performed in patients with clinical suspicion of recurrence. However, as pointed out by Morgenthal et al34 the clinical outcomes of patients appear to be a useful and reliable method of follow-up, as only 22%–29% of symptomatic patients had pathological pH-monitoring.

The three-year follow-up period may be another limitation. However, studies evaluating the success in terms of reflux control and complications of fundoplication suggest that these long-term results resemble those shown 3 years after surgery.35

Finally, a limitation is that we did not use validated questionnaires for the assessment of typical or atypical symptoms. Logically, because these questionnaires were not used, it was not possible to describe in detail the characteristics of clinical recurrence, although their impact on quality of life could be described using the GERD-HRQL questionnaire. Neither did we use specific questionnaires for the assessment of dysphagia.

In conclusion, extensive dissection of the oesophagogastric junction contributes to correct positioning and better anchorage of the fundoplication, with low rates of hernia recurrence and reflux in this study. None of the patients had telescoping of the fundoplication or symptoms suggestive of vagal injury. Further studies with a larger number of patients and a longer follow-up will enable more solid and concrete results regarding the outcomes of the technique.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.