Over the last few decades, significant improvement has been made in both the evaluation and treatment of esophageal achalasia. The Chicago classification, today in version 4.0, is now the standard for diagnosis of achalasia, providing a classification into 3 subtypes with important therapeutic and prognostic implications. Therapy, which was at first mostly limited to pneumatic dilatation, today includes minimally invasive surgery and peroral endoscopic myotomy, allowing for a more tailored approach to patients and better treatment of recurrent symptoms. This review chronicles my personal experience with achalasia over the last 35 years, describing the progress made in the treatment of patients with achalasia.

En las últimas décadas se han logrado mejoras significativas tanto en la evaluación como en el tratamiento de la acalasia esofágica. La Clasificación de Chicago, hoy en la versión 4.0, es ahora el estándar para el diagnóstico de la acalasia, permitiendo una clasificación en 3 subtipos con importantes implicaciones terapéuticas y pronósticas. El tratamiento, que al principio se limitaba principalmente a la dilatación neumática, incluye hoy en día la cirugía mínimamente invasiva y la miotomía endoscópica por vía oral, lo que permite un abordaje más personalizado de los pacientes y un mejor tratamiento de los síntomas recurrentes. Esta revisión narra mi experiencia personal con la acalasia durante los últimos 35 años, describiendo el progreso realizado en el tratamiento de los pacientes con acalasia.

It was February of 1989, and I was a third-year resident in General Surgery at the University of California San Francisco. A 32-year-old man with a long history of esophageal achalasia was referred to Dr Lawrence W Way for myotomy because of failed pneumatic dilatation, which had been performed multiple times over the previous 5 years. He was still experiencing dysphagia and regurgitation and was losing weight. At that time, pneumatic dilatation was used as primary treatment, reserving surgery for the treatment of persistent symptoms or for complications such as esophageal perforation.1 One week later. I assisted Dr Way, who performed an esophageal myotomy through a left posterolateral thoracotomy. The myotomy was 8 cm in length and extended for about 5 mm onto the gastric wall, following the technique championed by Dr Ellis for many years.2 A fundoplication was not added. Five days later, the patient was discharged and able to eat a regular diet without any problems for the first time after so many years. I remember seeing him in clinic in follow-up, a happy young man whose life had been changed by a 2-h operation performed by a very skilled surgeon. In retrospect, 35 years later, I now realize that this was a key moment in my career as this experience changed my plans from focusing on hepato-biliary diseases to the treatment of patients with esophageal diseases.

From the open to the minimally invasive approachIn the summer of 1990, Dr Lawrence Way had the intuition that minimally invasive surgery had the potential to be successfully used for operations other than cholecystectomy, and he travelled to Dundee, Scotland to observe Dr Alfred Cuschieri, a visionary surgeon who was applying minimally invasive techniques to the treatment of esophageal motility disorders.3 He came back enthusiastic about what he had seen, convinced that this was the future of esophageal surgery. In January of 1991, Dr Pellegrini and Dr Way performed the first minimally invasive Heller myotomy in the United States at UCSF using a left thoracoscopic approach. The operation mirrored the open approach, with a myotomy that extended for about 5 mm onto the gastric wall and no fundoplication. During 1991, we prospectively collected the data of all the achalasia patients who had undergone thoracoscopic myotomy during the last 12 months, and in April of 1992 Dr Pellegrini successfully presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.4 That presentation was the beginning of a new chapter for the treatment of achalasia, and after the meeting the number of referrals to our unit increased from all over the country. Being a new technique, we carefully followed-up our patients, and limitations of the thoracoscopic approach eventually became evident: for instance, the procedure required a double lumen endotracheal tube as it was performed with single lung ventilation with the patient positioned on a right lateral decubitus, and it required placement of a chest tube, making the anesthesia more complex and the hospital stay longer. In addition, we realized that it was not easy to carefully gauge the distal extent of the myotomy, even under endoscopic guidance: a shorter myotomy was associated with residual dysphagia, while a longer myotomy caused pathologic gastroesophageal reflux (GERD).4 Because of these shortcomings and having gained experience with the laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD, we switched to a laparoscopic approach following the example of the Padua group in Italy.5 This change allowed for a longer myotomy onto the gastric wall, avoiding the problem of residual dysphagia, and the addition of a Dor fundoplication to prevent reflux in most patients. When we compared 30 patients after thoracoscopic myotomy to 30 patients after laparoscopic myotomy with Dor fundoplication, we confirmed the wisdom of this approach: while the relief of symptoms was similar and excellent in both groups, pathologic reflux (by 24-h pH monitoring) was present in 60% of patients after THM but in only 10% of patients after the laparoscopic approach.6 These results were later confirmed by a study combining patients from UCSF and the University of Washington in Seattle.7

Endoscopic botulinum toxin injectionWhile it seemed that surgery was taking over, in 1993 Dr Pasricha published a case report describing the use of botulinum toxin injected in the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) in a patient with achalasia.8 One week after the injection, manometry showed that the LES pressure had decreased by 50%, from 64.9 to 32.5 mmHg, and 7 months after the operation the patient was still asymptomatic. Even though Pasricha concluded that patients treated with endoscopic botulinum toxin injections (EBTI) probably needed repeated injections and that this treatment “may be useful in patients who are either not suitable for or refuse conventional treatment”,8 the use of EBTI was rapidly and impressively embraced by the gastroenterology community. The enthusiasm for EBTI was probably based on the following considerations: a) it was the first time that a treatment targeted the pathophysiology of the disease, as the EBTI blocked the release of acetylcholine at the level of the cholinergic synapses, decreasing LES pressure; and 2) the LES injection was much easier than PD, faster, and clearly not associated with the risk of perforation. However, the initial enthusiasm for this new treatment slowly faded as some major limitations of EBTI became apparent. For instance, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia, Campos et al. showed that the relief of symptoms by EBTI was not long-lasting: EBTI relieved symptoms in 79% of patients 1 month after treatment, but symptom relief declined to 70% by 3 months, 53% by 6 months, and 41% after 12 months, probably because of antibody formation.9 A randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic Heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia showed that the probability of being symptom-free 2 years later was 87.5% after surgery and 34% after Botox.10 In addition to documenting the decreasing efficacy of EBTI over time, at UCSF we were the first to describe a problem related to EBTI which had the potential of compromising the result of a myotomy in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms.11 We realized that, while in untreated patients it was easy to distinguish the different layers of the esophageal wall, which allowed for transection of the longitudinal and circular fibers while leaving the mucosa intact, in contrast, an inflammatory process often occurred at the level of the gastroesophageal junction, particularly in patients who had an initial response after EBTI, making it very difficult to recognize the normal anatomic planes during surgery. Consequently, mucosal perforation occurred more frequently, and good results were obtained in only 50% of these patients.11 Eventually, these findings were confirmed by others, leading to a decrease in the use of EBTI as primary treatment modality.12 Today, it is accepted that EBTI should only be used in patients who are not candidates for other treatment modalities, reinforcing the initial recommendation made by Dr Pasricha in 1993.8–10,12

Looking back at the decade between 1991 and 2001, the use of EBTI clearly resulted in a drop in referrals for a couple of years, often making myotomy more challenging in patients who had recurrent symptoms.13 However, at the end of the 1990s, minimally invasive surgery was frequently adopted as the primary treatment modality, and laparoscopic myotomy with fundoplication became recognized as the standard of care, while the thoracoscopic approach was reserved for patients who had a hostile abdomen because of prior abdominal operations.

It was around the turn of the century that a surgeon from Brazil – Fernando Herbella – joined me at UCSF to work in the Center for Esophageal Motility and Secretion. The time spent working together cemented a friendship and a collaboration that has lasted a couple of decades. Today Dr Herbella is a Professor of Surgery in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and probably one of the most knowledgeable experts on esophageal motility in the world.

Over the following years, the laparoscopic myotomy technique slowly evolved, particularly focusing on 2 technical aspects: the length of the myotomy and the fundoplication. The group at the University of Washington in Seattle, led by Dr Pellegrini, showed that a longer myotomy extending 2.5–3 cm onto the gastric wall provided better relief of symptoms.14 Long-term follow-up confirmed this approach, probably due to a reduced incidence of distal esophageal scarring.15 In addition, the role of fundoplication was carefully analyzed. Dr Richards et al. reported the results of a prospective, randomized trial comparing control of symptoms and incidence of postoperative reflux in patients after a laparoscopic myotomy alone and in patients after laparoscopic myotomy and Dor fundoplication.16 While the relief of symptoms was similar in the 2 groups – around 90% – ambulatory pH monitoring showed pathologic reflux in 47.6% of patients after Heller and in 9.1% after Heller plus Dor (P = .005), therefore confirming the need for fundoplication. Questions were raised about the type of fundoplication, mostly regarding the choice between a partial posterior (Toupet) or partial anterior (Dor). In a prospective, randomized trial sponsored by SAGES Rawlings and colleagues, patients were randomized to either a Toupet or a Dor after laparoscopic Heler myotomy, showing that relief of symptoms was similar in the 2 groups and there was no difference in reflux control.17 Today, the general opinion is that the choice of partial fundoplication type should not be codified but should rather be left to the individual surgeon.

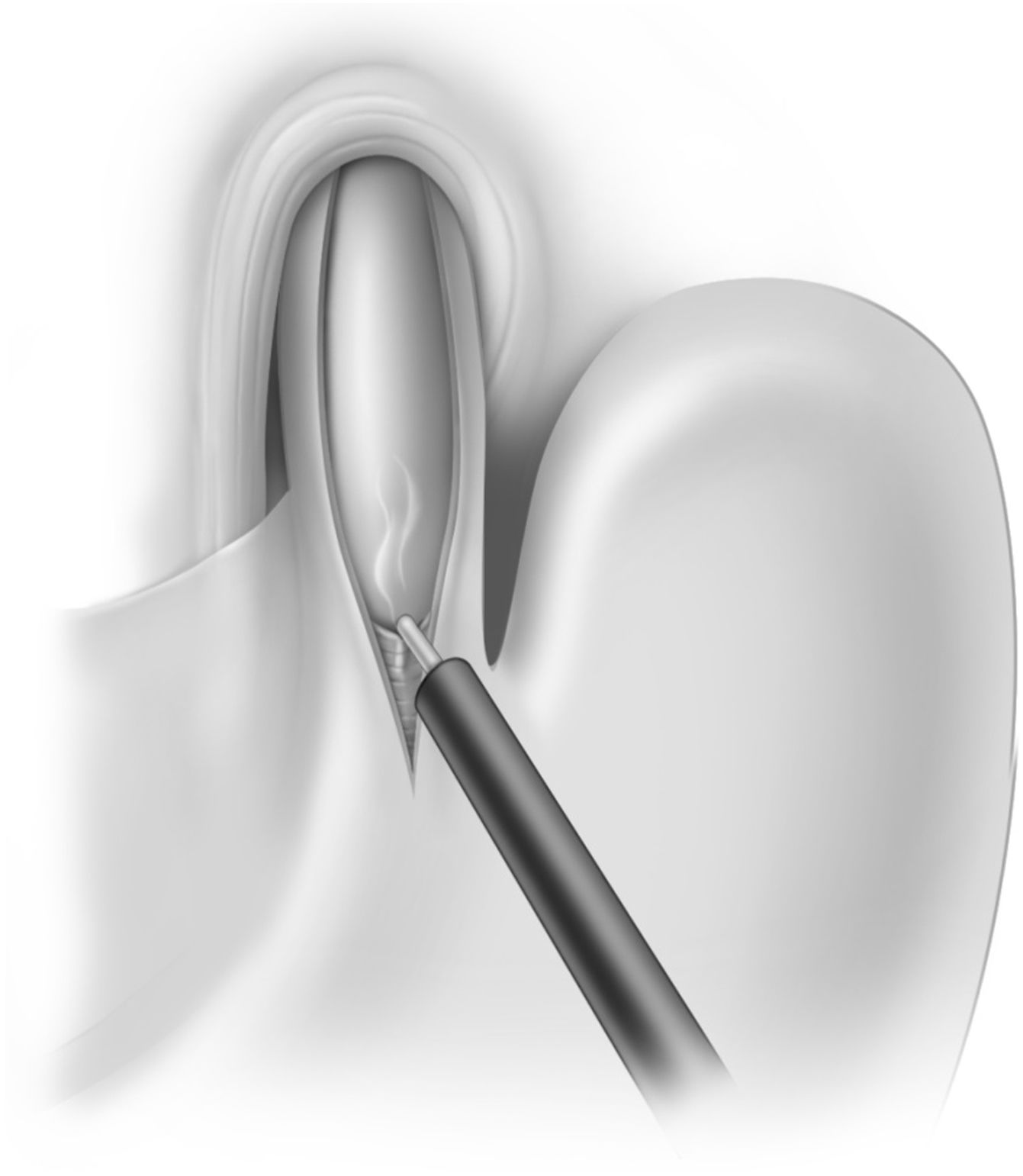

Similar to the findings of the studies mentioned above, our own technique has evolved somewhat over the years. The key technical steps were the following:18

- •

We always divided the short gastric vessels to avoid any tension when the fundus of the stomach was used for the fundoplication.

- •

After removing the fat pad to expose the gastroesophageal junction, we performed a myotomy in the 11 o’clock position, usually in a hockey stick configuration to ensure transection of the sling fibers. The total length of the myotomy was 8–8.5 cm, extending for 2.5 cm onto the gastric wall. The edges of the myotomy were then separated so that about 40% of the mucosa was exposed. We did not routinely perform intraoperative endoscopy (Fig. 1).

- •

We used the Dor fundoplication (180° anterior), with one row of 3 sutures on the left and another row of 3 sutures on the right.18 We chose the Dor fundoplication rather than the Toupet because it does not require posterior dissection (avoiding possible injury to the posterior vagus nerve), and because it covers the exposed esophageal mucosa.

During these years, we had many patients referred to us for esophagectomy with a dilated and often sigmoid esophagus, the so-called “end-stage achalasia”. Even though this approach was considered standard of care at that time, we decided that it was worth it to try a laparoscopic Heller myotomy as a first step, particularly because many of these patients had never been treated before, reserving resection for those who had persistent symptoms.19 The operation was clearly more complex as it required extensive mediastinal dissection to straighten the esophagus and bring it further back below the diaphragm. In addition, if the hiatus was enlarged or a hiatal hernia was present, a couple of stitches were placed behind the esophagus to approximate the crura, and a Dor fundoplication was performed. Additional treatment was required in 20% of patients who needed postoperative dilatation, in 4% of whom a second myotomy was performed. Overall good results were obtained in about 90% of patients, regardless of the esophageal diameter and sigmoid shape, and no patients required esophagectomy.19 The rationale and results of this approach were later confirmed by other groups.20

High-resolution manometry: the Chicago classificationDuring my time at UCSF, we also witnessed a change in the evaluation of patients with achalasia. I spent 2 years as a fellow at the Center for Esophageal Motility and Secretions, evaluating patients with benign esophageal disorders. At that time, esophageal manometry was performed with water-perfused catheters, often with a configuration with 4 distal circumferential sensors to measure the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and 4 sensors spaced at intervals of 5 cm, at 90-degree angles from each other (usually placed 3, 8, 13 and 18 cm above the upper border of the LES). Initially, the resting pressure, relaxation, total length, and abdominal length of the LES were assessed. Subsequently, 10 swallows of 5 mL of water were given at 30-second intervals for the evaluation of esophageal peristalsis (amplitude, duration, velocity, non-transmitted or partially transmitted waves). Based on this test, 4 primary esophageal motility disorders were identified: achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm (DES), nutcracker esophagus, and hypertensive LES.

Achalasia was defined by partial or absent LES relaxation in response to swallowing and absent esophageal peristalsis. Hypertensive LES (resting pressure > 45 mmHg) was present in about 50% of patients.21

In 2008, Pandolfino et al. introduced a different classification of esophageal motility disorders (Chicago Classification) based on High Resolution Manometry (HMR).22 The test was performed using a solid-state catheter with 36 closely spaced pressure sensors, with data displayed in the format of Clouse plots (color isobaric contours), which soon replaced the water-perfused catheters.20 Today HRM and the Chicago classification, now in its version 4.0, are considered standard in clinical practice worldwide.23

Based on the Chicago classification, today achalasia is categorized into 3 subtypes, with important implications for choice of treatment and prognosis:

- •

Type I: incomplete LES relaxation, aperistalsis and absence of esophageal pressurization

- •

Type II: incomplete LES relaxation, aperistalsis and pan-esophageal pressurization in at least 20% of swallows

- •

Type III: incomplete LES relaxation, aperistalsis and spastic contractions in at least 20% of swallows

Another milestone in the treatment of achalasia occurred in 2010, when Dr Haruhiro Inoue from Showa University in Japan published the results of a new endoscopic technique called Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) for the treatment of esophageal achalasia.24 The endoscopic procedure was based on a mucosotomy in the proximal esophagus and the creation of a 12 cm long submucosal tunnel, followed by the endoscopic myotomy of circular muscle fibers for about 8 cm, 6.0 cm in the distal esophagus and 2.0 cm in the cardia. Clinical success was obtained in 100% of 17 patients, and only one patient required treatment with PPI for LA grade B esophagitis. This report was initially received with some skepticism for a few reasons: 1) Dr Inoue was a surgeon who had never published studies on achalasia; 2) the LES pressure after the procedure decreased from a mean of 52.4 mmHg to 19.9 mmHg. It was commonly accepted from prior studies of pneumatic dilatation and laparoscopic Heller myotomy that, to relieve symptoms, the post procedure LES pressure had to decrease to 10 mmHg; and 3) considering that only a myotomy without fundoplication had been performed, it seemed somewhat strange that only 1 out of 17 patients (5.9%) had developed pathologic reflux requiring treatment with PPI.

However, the implementation of this technique spread rapidly worldwide, as many studies showed that POEM was able to improve symptoms in most patients, with the Eckardt score going down to 3 or less in about 90% of patients. Many endoscopists travelled to Yokohama to observe Dr Inoue in action, while Dr Inoue also travelled to many centers around the world to mentor the initial procedures. In 2012, 20 years after the presentation of Dr Pellegrini describing the initial experience with thoracoscopic myotomy, Dr Swanstrom presented at the American Surgical Association the results of POEM in 18 patients operated on between October 2010 and October 2011.25 After a mean follow-up of 11 months, dysphagia relief persisted in all patients. Ambulatory pH monitoring showed pathologic postoperative reflux in 46% of patients. These results were soon confirmed in other centers worldwide. For instance, Familiari and colleagues from the Catholic University in Rome, Italy, reported on the first 100 patients treated with this new technique in 2016.26 After a mean follow-up of 11 months, clinical success was documented in 94.5% of patients, and pH monitoring showed pathologic reflux in 53.4% of patients. Eventually, study after study, it became evident that 2 results were routinely present after POEM: 1) relief of symptoms in 90% of patients or more; and 2) pathologic reflux in about 50% of patients.

GERD after POEM was clearly very concerning, as reflux occurred in an aperistaltic esophagus, with very slow clearance and prolonged contact time of the refluxate with the esophageal mucosa. With a longer follow-up, the sequelae of the abnormal reflux became slowly apparent. For instance, when Werner and colleagues reported the results of a multicenter study of POEM for achalasia, which included 80 patients with a follow-up of 29 months, they documented endoscopic esophagitis in 37.5%, a 2 cm long peptic stricture in one patient, and de novo Barrett’s metaplasia in 2 patients.27 Eventually, the first case of post-POEM Barrett cancer was reported in 2019.28 Based on these data, questions were raised about the role of POEM in the treatment algorithm of esophageal achalasia: specifically, should POEM be used as primary treatment for achalasia, or should it rather have a supportive role in specific circumstances?

To try to answer this question, in 2018 we performed a meta-analysis of published studies with the goal of comparing the efficacy of POEM and laparoscopic Heller myotomy and the incidence of post-procedure reflux.29 This study showed that the control of symptoms was excellent with either procedure (at the 2-year follow-up: 92.7% after POEM, and 90% after laparoscopic Heller myotomy). However, pH monitoring showed that the incidence of pathologic reflux was more than 4-fold higher after POEM compared to laparoscopic Heller myotomy (47.5% versus 11.1%).29 These findings were recently confirmed in a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comparing endoscopic and surgical myotomy in patients with esophageal achalasia.30 A total of 221 patients were randomized to either POEM (112 patients) or laparoscopic Heller myotomy (109 patients). At the 2-year follow-up, clinical success was observed in 83% of patients in the POEM group and in 81.7% in the laparoscopic Heller myotomy group. However, the incidence of pathologic reflux was 57% after POEM and 20% after laparoscopic Heller myotomy.30

Based on these findings, we continued using laparoscopic Heller myotomy as primary treatment for type I and II achalasia, but switched to POEM for type III achalasia as evidence showed that POEM gave better results than laparoscopic Heller myotomy, probably because it allowed for a longer myotomy onto the esophageal wall.31,32 It was also shown that POEM is actually very effective for treating patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms after laparoscopic Heller myotomy,33 traditionally treated with pneumatic dilatation. And a recent randomized and multicenter clinical study has confirmed that POEM is more effective than pneumatic dilatation to treat recurrent symptoms after Heller myotomy.34 POEM also avoids the need to perform a redo myotomy in cases of failed pneumatic dilatation, an operation that is often challenging because of adhesions and scar tissue, while POEM can be safely done on the posterior wall of the esophagus and stomach.

Interestingly, we have observed over time a progressive decrease in the utilization of pneumatic dilatation, considered for many decades the primary treatment for achalasia. This is somewhat surprising, especially since a European prospective and randomized trial comparing pneumatic dilatation and LHM with Dor fundoplication showed that the therapeutic success of PD and laparoscopic Heller myotomy was similar after 2 years (dilatation 86%; myotomy 90%) and after 5 years (dilatation 82%; myotomy 84%).35,36 We feel that this trend will eventually continue over time: because of the extensive use of laparoscopic Heller myotomy during the last 15 years and POEM in the last 10 years, fewer and fewer dilatations are performed every year; also, as trainees are not exposed to this technique, the use of pneumatic dilatation will eventually fade away.

Robotic Heller myotomyAs far as innovations are concerned, the last few years have seen the use of a robot to perform minimally invasive myotomy.37 We think that it is the surgeon’s choice as the robot offers very good visualization, eliminating tremor. In our own experience, however, having found no difference in results, we have used the classic laparoscopic approach to perform the operation, as it is both faster and cheaper.

Treatment of recurrent symptoms after prior interventionAs we treated more and more patients over the years, we realized that some patients eventually experienced recurrent symptoms, particularly if the initial intervention was performed when they were young. In our experience, the most common cause was scarring of the distal aspect of the myotomy, but we sometimes found stricture due to pathologic reflux. Our goal was always to improve the symptoms and avoid esophagectomy.

An extensive work-up was always performed, starting with a review of the pre-intervention evaluation. In addition, the operative report often gave clues, such as a short myotomy or a wrongly constructed fundoplication. A barium swallow, endoscopy, and esophageal manometry were then performed. We found that pneumatic dilatation was the easiest initial approach to these patients and reserved a redo myotomy for the refractory cases. A second operation was in fact often very challenging because of adhesions and scar tissue and sometimes ended up with an esophageal resection. Today, we feel that POEM performed on the posterior wall of the esophagus is a safe and an excellent option.34

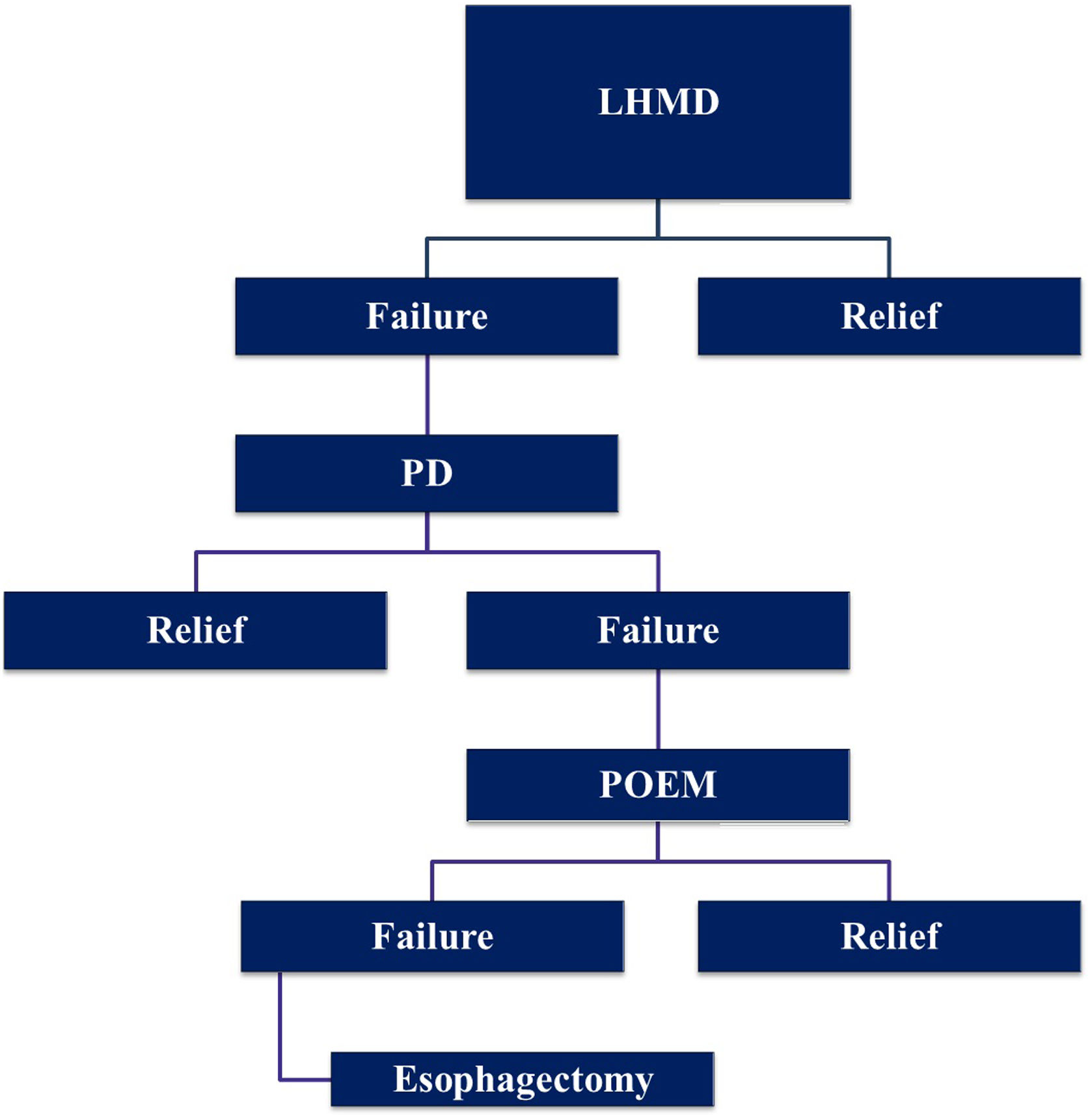

Treatment algorithmWe do consider LHM with Dor fundoplication the primary treatment modality for types I and II achalasia, reserving POEM for type III. If dysphagia recurs, we initially use pneumatic dilatation. In case of failure of pneumatic dilatation, we prefer POEM rather than a redo myotomy. Esophagectomy is considered a last resort after all the other modalities have failed (Fig. 2).

ConclusionsBased on the literature and our own experience over many decades, we want to make the following suggestions:

- •

A thorough work-up, including barium swallow, endoscopy and manometry, should be performed in every patient suspected of having achalasia.

- •

The best results are obtained in centers with a dedicated multidisciplinary group of experts able to tailor treatment to individual patients. With a thorough evaluation and using the treatment modalities available, esophagectomy can be avoided in most patients.

- •

When proper expertise and experience is present, a laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication should be the treatment of choice for types I and II achalasia.

- •

POEM should be used primarily for type III achalasia, for patients with prior abdominal operations, and for the treatment of recurrent symptoms after laparoscopic Heller myotomy.

- •

Contrary to recent reports,38 we do believe that POEM should not be used in children with achalasia because of the high incidence of post-POEM reflux.39 Life-long exposure to reflux could in fact expose them to the risk of esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and even adenocarcinoma.

- •

Finally, even in the absence of precise guidelines, we do perform a complete work-up, including endoscopy, every three years in asymptomatic patients or whenever symptoms recur.

- •

We do believe that patients are best served by a multidisciplinary team in a center specialized in the treatment of esophageal disorders. After thorough evaluation, the proper treatment will be chosen based on the patient’s characteristics and the findings of the work-up.

Overall, it has been a long journey, and during these years we have been lucky to witness so many great innovations in the treatment of esophageal achalasia. It is still a unique and exciting privilege to allow patients to eat without problems, restoring their quality of life.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Patti MG, Herbella FA. Evolución del tratamiento de la acalasia esofágica. Crónica de un viaje de 35 años. Cir Esp. 2024.