Little is known about consumption patterns of glass and the development of regional glass production during the Islamic period in present-day Portugal (Gharb al-Andalus). This work considers the glass finds from Silves Castle (Portugal), dated to the 10th to mid-13th century CE. The chemical composition of the glass assemblage was determined by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), and lead isotopic analysis was performed on selected high lead samples. The results were compared to legacy data to identify possible cross-links and trade networks with other contemporary Islamic sites in the Iberian Peninsula and the Eastern Mediterranean. The glass assemblage from Silves proved to be rather heterogeneous, with two major compositional groups and three so-called soda-rich Iberian lead glass samples. Group 1 shows characteristics of glass of Iberian origin but with distinct recycling markers, while Group 2 resembles glass from 10th-century Córdoba with little recycling. Judging from these similarities, the main supply seems to have been largely covered by Iberian glass. The predominance of Iberian compositions illustrates the decline in trade relations between the city and the Eastern Mediterranean regarding glass products that affected even an elite context such as the Castle of Silves.

Poco se sabe sobre las dinámicas de consumo de vidrio y el desarrollo de la producción vidriera regional durante el periodo islámico del actual territorio portugués (Gharb al-Andalus). En este trabajo analizamos los materiales vítreos recuperados en el castillo de Silves (Portugal), datados entre el siglo X y mediados del siglo XIII de nuestra era. La composición química del material se determinó mediante espectrometría de masas con fuente de plasma de acoplamiento inductivo (LA-ICP-MS), y fue complementada con análisis isotópicos en determinadas muestras. Los resultados se compararon con bases de datos existentes de otros yacimientos islámicos contemporáneos de la Península Ibérica y del Este del Mediterráneo para identificar posibles vínculos y redes comerciales. El conjunto vítreo de Silves resultó ser bastante heterogéneo, con dos grupos composicionales distintos y tres muestras identificadas como vidrio de plomo con alto contenido de sodio, también presente en otros sitios ibéricos. El Grupo 1 presenta rasgos propios de los vidrios producidos en el ámbito islámico peninsular, pero con evidencias claras de procesos de reciclado. Por su parte, el Grupo 2 guarda similitudes con los vidrios de Córdoba del siglo X, y en su mayoría, con escasos indicios de reciclaje. A juzgar por estas afinidades composicionales, el abastecimiento principal parece haber dependido en gran medida del vidrio ibérico, lo que ilustra el declive de las relaciones comerciales con el Este del Mediterráneo en lo que a productos de vidrio se refiere.

Late Roman and early medieval glassmaking was divided into large-scale primary production in Syria-Palestine and Egypt, and small-scale secondary workshops across the empire [1–3]. Primary glass was produced using local sand and so-called natron, a mineral-soda as flux [4]. This ancient system of production changed in the late 8th century CE when the use of natron gradually ceased, and glass makers resorted to the use of plant-ash in Greater Syria [5,6] and in the last quarter of the 10th century CE in Egypt [7]; in what follows, all dates are understood as Common Era (CE). The impact of this transition on the supply of glass and the emergence of a local glass production in al-Andalus is not entirely clear [3,8–10].

The Iberian Peninsula was integrated into the Umayyad Empire by the early 8th century. This geopolitical transformation was accompanied by a significant change in the circulation and production of glass [10–12]. The limited material evidence from contexts of the 8th and 9th centuries in comparison to previous periods suggests that glass supplies from the eastern Mediterranean declined, while recycling increased [3,12–14]. A new primary glass production of a specific kind of lead glass emerged in the Rabad of Šaqunda (Córdoba, Spain) at the turn of the 9th century [11]. From the late 9th and 10th centuries, another type of soda-ash lead glass and eventually plant-ash glasses are found in the archaeological records [10,13–17].

Next to nothing is known about the distribution and production of Islamic glass in the west of Gharb al-Andalus and its connection with the rest of al-Andalus and the Eastern Mediterranean [3,18]. To fully understand the transformation of the glass industry and trade in the Islamic west, the integration of analytical studies of Portuguese glass assemblages is crucial. The vitreous material from Silves (Xelb) offers a promising example of glass distribution patterns in the western periphery of al-Andalus, due to the city's geopolitical significance, wealth, local-economic centrality, and cultural prominence from the 10th century until the Christian conquest in 1248. In the present study, a series of 10th- to 13th-century glass found inside Silves Castle were analysed by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) to establish their chemical composition including all major, minor, and trace elements. Previous studies have shown that trace element analysis using LA-ICP-MS can be successfully used to categorise Islamic glass and provides important information about glass production and the origin of the raw materials [7,10,11,13,19,20]. In addition, lead isotope analysis was carried out for high lead glass, which has proved particularly useful in demonstrating the emergence of primary glass production in Spain at the beginning of the 9th century [11]. By compiling a comprehensive dataset, including trace elements, and comparing the data with other Islamic sites in the Iberian Peninsula and the Near East, the overall objective is to improve our understanding of glass supply, glass group distribution, and recycling practices in the al-Gharb region compared to other sites in al-Andalus.

The site and materialWith its strategic access to the sea through the river Arade and linked by roads to other main urban centres, the city of Silves served as a vital hub for trade and governance in its heyday [21–23]. Written sources indicate its pivotal commercial role by the mid-9th century when it became the last capital of its caliphate's Kūra[21,22]. From 1048 to 1063, Silves enjoyed a brief period as an independent Taifa before becoming part of the Taifa of Sevilla, and it was finally incorporated in the first North African dynasty of the Almoravids in 1091 [24]. In 1156, the city came under Almohad hegemony [21] and its importance was based on its control over the region's economy. The unsuccessful attempt by Christian kingdoms to seize and maintain control from 1189 to 1191 underlines the strategic and political significance of Silves at that time [23]. Unfortunately, the literary and archaeologically well-documented siege of 1189 [21–23] revealed extensive plundering, affecting the material evidence. Despite the almost immediate regain of Almohad control and relative stability, Silves became an independent Taifa once more in 1212 [25]. The archaeological evidence of new reinforcements in the medina's defensive structure [22] confirms a concerted effort to fortify the city against future threats, but the limited historical sources offer scarce details on the city's socio-economic recovery during this later period [21].

The excavations directed by Rosa Varela Gomes between 1984 and 2007 focused on the eastern side of the citadel (Alcáçova) (Fig. 1a and b) and yielded 287 glass finds, together with ceramics originating from Peninsular production centres (Seville, Murcia and Calatayud), North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean (Egypt, Syria, Iran and Iraq) [22,26,27]. The glass contexts were dated by radiocarbon analysis and stratigraphic sequencing to phases spanning the 10th to 13th centuries [22,28,29]. More precisely, these contexts can be attributed to four distinct periods (Table 1): the oldest chronological layer is attributed to the Caliphal period; the second period includes the “Balcony Palace” and a residential compartment of the first Taifa Kingdom and Sevilla's ruling class in the 11th century; the third period consists of a palatine edifice that was constructed and used during the Almoravid and Almohad occupation prior to the first attempt of Christian conquest in the 12th century; and finally the contexts dated to the phase between the Christian siege of 1191 and the definitive reconquest in 1248, included a residential areas and a bath complex.

Chronological distribution of the analysed glass fragments, indicating the number of samples selected for each glass type per archaeological context. For further details see supplementary Table S1.

| Chronological context | Total number of fragments recovered | Number of samples analysed | Glass type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caliphal period10th century | 2 | 1 | Soda-ash Pb glass (n=1) |

| Taifa period11th century | 12 | 10 | Group 1 (n=8)Soda-ash Pb glass (n=1)Egypt 2 natron (n=1) |

| Almoravid/Almohad12th century | 43 | 12 | Group 1 (n=8)Group 2 (n=2)Levantine plant-ash (n=1)Mesopotamian plant-ash (n=1) |

| 12th–13th century | 230 | 26 | Group 1 (n=13)Group 2 (n=8)Soda-ash Pb glass (n=1)Outliers (n=4) |

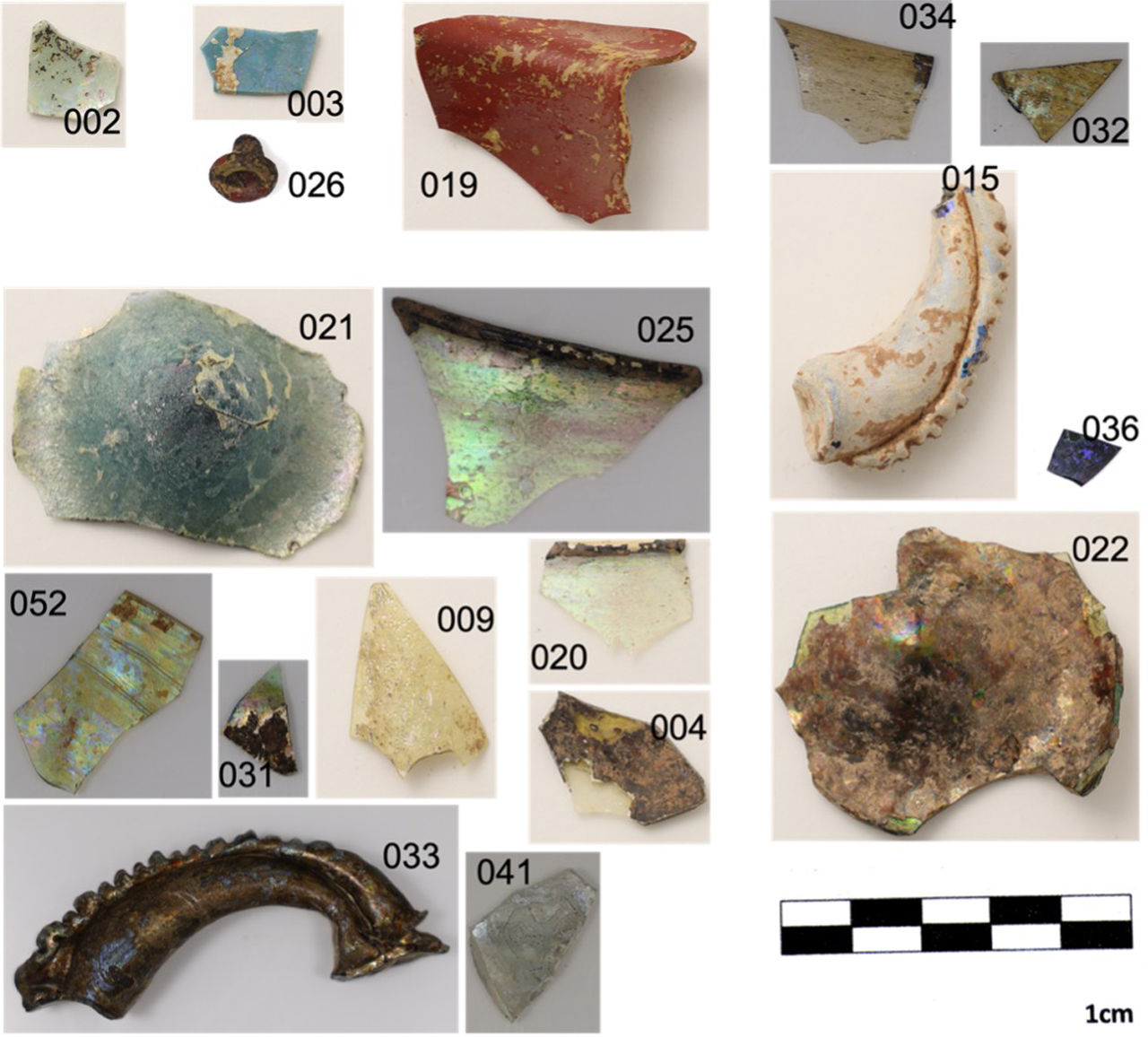

All glass objects originated either from palatial areas exclusively used by the elite at the time or from adjacent domestic contexts [22,27]. Most fragments of the collection were heavily weathered. In consultation with the archaeologist in charge, it was agreed upon that only a small number of fragments from the earliest levels (10th and 11th centuries) were suitable for analysis. In fact, many fragments had already been discarded due to their highly degraded state. The largest number of fragments comes from the final phases of the Islamic occupation. Some of the intact or restored pieces are currently on display at the Silves Museum and could not be sampled without risking their preservation. Only material accessible in the storage facilities was included in the present study.

To ensure the most representative and reliable dataset, fragments in sufficiently good condition were prioritised. Hence, the selected samples were the better-preserved typologies (handles, rims, stoppers, thick body fragments) that could illuminate different functions (e.g., cosmetic, utilitarian) [26,27], and were linked to either palatial or domestic contexts, as indicated by the literature [22,27–29]. The quantity of glass recovered varies across chronological phases (Table 1). A total of 49 samples from the different chronologies were selected to be analysed based on their state of preservation rather than the total number of fragments available. As a result, some periods may not be fully represented in the dataset, limiting the possibility of a detailed diachronic interpretation. However, our aim was to include samples from all available periods in order to gain a broader overview of the compositional characteristics of the glass between the 10th and 13th centuries.

The selected samples were quite fragmented (Fig. 2), but some were attributed to small flasks and vials related to cosmetics [27] and two stoppers and handles were identified (table 1 S1). More than a third of the fragments are weakly coloured (n=18), the same number of samples (n=18) display brown-yellow hues, and the rest were coloured glass in green (n=2), blue (n=2), olive dark green (n=3), and four opaque fragments (two red, one turquoise, one white). Two colourless fragments with applied trails of either emerald green or dark blue were counted as separate analytical samples.

MethodsGiven the fragmented and heavily weathered condition of the glass assemblage, a careful sampling procedure was carried out taking as little as 1mm3 from the fragments when possible. Most fragments were embedded in epoxy resin to ensure stability during analysis. For a few selected samples that were better preserved, analysis was conducted directly on the surface of the unprepared fragments. One of the main advantages of the use of LA-ICP-MS is that it is virtually non-destructive and only microinvasive, leaving a laser hole with a maximum diameter of 100μm. LA-ICP-MS was carried out at IRAMAT-CEB, CNRS in Orleans (France), with a Thermo Fisher Scientific Element XR mass spectrometer coupled with a 193nm Resonetics M50E excimer laser operating in spot mode (at 5mJ, 10Hz, 100μm beam diameter). The analytical protocol included a pre-ablation time of 20s and an acquisition of 9 mass scans over 27s. The ablated material is transported to the mass spectrometer by an argon/helium gas flow (1l/min Ar+0.65l/min He). In a single analysis 58 isotopes were measure. The 28Si isotope served as the internal standard for calibration. The response coefficient (K) for each element was calculated based on five glass standards (NIST SRM610, Corning B, C, D, and APL1) to convert the signals into quantitative data (for accuracy and precision see table 2 S1).

Lead isotope analysis was conducted on two glass samples with high lead contents at the Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (BRGM) in Orleans, France following the protocol as described [11]. Lead isotope ratios (206Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, 208Pb/204Pb) were measured using a multi-collector Finnigan MAT262 thermal ionization mass spectrometer in static mode. The Pb isotopic ratios were corrected for a mass bias of 0.13wt% per atomic mass unit as determined by repeated measurements of the NIST NBS982 standard. The individual error in all ratios was better than 0.01wt% (2σ), while external reproducibility (2σ) was 0.06wt% for the 206Pb/204Pb ratio, 0.07wt% for the 207Pb/204Pb ratio, and 0.09wt% for the 208Pb/204Pb ratio.

Optical absorption spectroscopy (OAS) was performed on seven glass fragments that were suitable for UV/vis analysis as they exhibited sufficiently flat, semi-clean surfaces free from heavy corrosion. Absorbance spectra for the transparent glass samples were acquired in transmission mode using a Varian Cary-5000 UV/Vis spectrophotometer, over a wavelength range of 300–1200nm with a resolution of 1nm. For opaque and dark brown samples, measurements were taken in reflectance mode using an Avantes AvaSpec-2048 fibre optic spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere, covering the 350–750nm range with a resolution of 0.6nm. Stereomicroscope images were taken to complement the spectral data.

ResultsForty-five out of 49 samples are soda-rich plant-ash glass, which is expected for an assemblage of this period. These are soda–lime–silica glass with silica between 56.8 and 63.2wt%, soda between 11.5 and 21.2wt%, and lime between 3.5 and 8.8wt% (table 3 S1). The plant-ash samples were separated into two main groups based on their trace element ratios, two imports (from the Levant and Mesopotamia) and three outliers were discriminated from the rest. Three samples (#010, #012 and #049) with high contents of lead oxide (51.1wt%, 44.8wt% and 12.6wt%, respectively) were identified as soda-rich lead glass [30,31]. One fragment (#013) turned out to be a natron glass, and identified as Egypt 2 due to its low aluminium, high titanium, zirconium, and lime and particularly the low Sr/Ca ratios [7].

Soda-rich plant-ash groupsThe high and variable contents of Na2O (11.5–21.2wt%), K2O (1.5–3.8wt%), and MgO (2.1–5.5wt%) show that the raw material (flux) used to lower the high melting point of the mixture was plant-ash rich in sodium, typical of Islamic glass of the period (Fig. 3) [6,32–34]. This glass was produced by adding ashes of halophytic plants of the Chenopodiaceae family [33,35]. Calcium is needed as a stabiliser of the glass system, and derives largely from the plant ashes as well [5,34]. The few differences in the contents of the elements brought about by the flux can be seen in the MgO and CaO levels (Fig. 3). Silves plant-ash samples form a relatively close group with median calcium oxide content of about 6wt% and a median of about 3.8wt% of magnesium oxide that is slightly higher than that of Levantine and Egyptian glass. Three samples have MgO above 4.5wt%, similar to Mesopotamian samples. The compositional variability of plant-ash makes it difficult to group the samples using only these elements [13,35].

Impurities of the silica source provide additional information for the grouping of plant-ash glass [1–3,32,37,38]. The high aluminium (1.8–5.5wt%) and silica-related trace elements point to the use of sand instead of quartz pebbles for the production of these glass samples [39,40] (Fig. 4). Different minerals in sand such as plagioclase feldspars, zircon, monazite and clay minerals are responsible for adding elements such as Al, Fe, Ti and Zr to the batch and trace elements such as Th, Hf, V, Nb, Cr, Ga, Y, Ta (even sometimes Cs) and rare earth elements (REE). Aluminium and titanium concentrations clearly distinguish two main groups, sufficiently homogeneous to constitute coherent compositional groups (Fig. 4a). This is confirmed by the trace element patterns brought about by accessory minerals found in sands (Fig. 4b). The main differences between the two groups pertain to Zr, Hf (related to zircon), Th and the REEs (related to monazite) [41]. The contents of these elements and the proportions between them (ex. Th/Zr, La/TiO2) show a relationship in the source of silica for these two groups.

Base glass characteristics of the glass from Silves. (a) Titanium versus aluminium oxide displaying all samples distinguishing Groups 1a, 1b, 2, soda-rich Pb and outliers. (b) Average of trace elements and REE patterns of Groups 1a, 1b, 2 and soda-rich Pb, normalized to MUQ, a standard geological reference material [42].

Group 1 (n=31) has lower TiO2/Al2O3 ratios compared to the other samples (Fig. 4a). It has intermediate absolute concentrations of silica-related elements such as Ti, V, Y, Ga, Zr, Nb, Hf, Ta, Th and the REE (Fig. 4b). As the alumina contents are quite scattered (Fig. 4a), this group was further divided into low alumina Group 1a (<3wt%) and high alumina Group 1b (3.4–4.9wt%). Group 1a has overall lower silica-related minor and trace elements in relation to 1b, except for Zr and Hf, which are present roughly in the same concentration in both subgroups (Fig. 4b). Even though there is some variation within this group, the correlations suggest the use of related silica sources. Group 2 presents the highest titanium oxide concentrations (0.32–0.48wt%), while its alumina contents are similar to Group 1b (Fig. 4a). This group has overall the highest trace elements, particularly Zr and Hf (Fig. 4b). It also exhibits a negative Eu-anomaly and enrichment of light REEs (La to Gd) against heavy REEs (Tb to Lu), associated with sand from the weathered granitic rocks of the upper continental crust [43].

Soda-rich lead glassSamples #010 and #012 have 51.1wt% and 44.8wt% lead oxide, respectively. The high levels of chlorine of these samples (2.4wt% and 2.1wt%) [11,13,15,44], and the high amounts of plant-ash related elements such as Na2O >5.9wt%, K2O (0.5–1wt%) and MgO (average 1wt%) seem to be the particular signature of high lead glass found in the Iberian Peninsula [16,44]. Silves #049 has lower contents of lead (12.7wt%) and chlorine (1.3wt%), however, the high content of lead is not related to any opacifier and the correlation between Pb and Sb is coherent with the other high lead samples. The concentration of silica-related trace elements in soda-rich lead glass is notably lower due to the significantly lower silica contents (Fig. 4a), yet the REE and trace elements exhibit a pattern similar to Group 1 (Fig. 4b), except for those introduced by the lead itself. Distinguishable features of these lead glasses are the high levels of arsenic, silver and bismuth associated with the lead-bearing component (Table 3 S1). More importantly, the lead isotope signature of two samples (#010, #012) is compatible with lead either from the districts of Linares – La Carolina or Los Pedroches north of Córdoba (Fig. 5).

Comparison of lead isotopes of Silves high lead glass with different mining areas in Spain. (a) 208Pb/204Pb versus 207Pb/204Pb; (b) 207Pb/206Pb versus 208Pb/206Pb.

Data sources: Linares-La Carolina (Jaén), Los Pedroches (Córdoba) and [45], Alcudia Valley (Ciudad Real); Iberian Pyrite Belt [46].

Five plant-ash samples (#001, #016, #019, #040, #041) have been classified as outliers (Fig. 4a). Sample #016 was singled out based on its cobalt signature. The presence of arsenic (999ppm) and bismuth (914ppm) suggests the use of European cobalt ores that were exploited only after the 15th century [47–49]. This sample is therefore not further considered in the discussion. Opaque red sample #019, is similar in composition to Group 1 but has elevated REE and trace elements which made us separate it from Group 1. Sample #001 is a fragment of clear colourless base with an applied decoration of green emerald with the same base glass. This sample has the highest content of alumina, titanium and trace elements, a pronounced negative Europium anomaly and around 7wt% of lead. Samples #040 and #041 are clear and colourless with the lowest content of iron oxide (0.48wt% and 0.25wt%) and impurities in general. Sample #040 is consistent with Levantine plant-ash glass [7,19] with high CaO (8.8wt%), low Al2O3 (2wt%), TiO2 (0.08wt%), ZrO2 (36ppm) and a positive Eu anomaly. Sample #041 appears to correspond to a Mesopotamian plant-ash glass of the Samarra type [36] with low alumina coupled with an elevated Cr/La ratio (>5), high magnesium (MgO >5%) and lowest phosphorus content (0.12wt%).

Chromophores, decolourants and opacifiersThe colour of glass results from a complex interplay involving the presence of transition metals (e.g., Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, Zn, Ag, Au), base-glass composition, and melting conditions (temperature, partial oxygen pressure). LA-ICP-MS can identify the transition metals most likely responsible for the perceived colours. This section intends to contextualize colour variation in relation to elemental presence. UV/visible optical absorbance spectroscopy was performed on seven samples in a sufficiently good condition to support the chemical data. Table 2 summarizes the results and interpretation [50], the full spectra and stereoscope images are given in the supplementary material 2.

UV/vis spectral results. Full spectra can be found in supplementary material.

| Sample | Colour category | Main chromophore(s) | Absorption maxima (nm) | Spectral features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #040 | Colourless | Weak λ1=380–450nm; λ2=900–1100nm | Low absorption no distinct peaks. Weak signal in the 380–450nm range and weak absorption band in the 900–1100nm range | |

| #009 and #020 | Weakly coloured | Fe3+ | λ1=380nm; λ2=420nm | Low absorption, two shoulders in the 380nm and 420nm |

| #011 | Purple | Mn3+ | λ1=482nm | Broad band between 470 and 520nm, with maximum in λ1 |

| #030 and #032 | Light yellow-brown | Fe3+ (Mn2+, no band) | λ1=380nm; λ2=420nm | Low absorption, with two shoulders in the 380nm and a wider one at 420nm |

| #005 | Dark yellow-brown | Fe? Mn? | Sat. | Saturated absorbance across the visible range |

| #031 and #001 | Green | Cu2+ | λ1 ∼800nm | Broad absorption bands in the 700–900nm region |

| #019 | Red opaque | Cu? Pb? | Sat. | Saturation below 580nm |

| #003 | Turquoise opaque | Cu? | Sat. | Saturation near 700nm and higher wavelenghts in the visible range |

Weak hues in glass are usually caused by iron impurities in the sand that glassmakers aimed to mitigate using other components such as manganese oxide [51–54]. Concentrations above background levels of manganese in sand >0.03wt% [54–56] indicate that Mn was added to the batch. The optical absorbance spectra in the UV–visible range for sample #040 shows a low absorption and only a weak signal in the 380–450nm range caused by Fe3+. There may be a minor contribution of Fe2+ due to a weak absorption band in the 900–1100nm part of the spectrum (S2 and Fig. 1).

Almost one-third of the fragments (n=16) appears to be translucent with tinges of different hues. The samples within this colour category are called “weakly coloured”. They all contain a combination of moderate iron (0.6–1.2wt%) and manganese (<0.6wt%; Table 3 S1) levels. The two samples #009 and #021 show low absorption with very weak features related to iron, mostly in the form of Fe3+ (S2 and Fig. 2). A purple sample #011 has somewhat higher iron (1.2wt%) and manganese (0.7wt%) and presents an absorption spectrum with a broad band between 470 and 520nm (S2 and Fig. 4) characteristic of manganese in its oxidised form (Mn3+) [57,58].

The second largest group includes samples with light to dark brownish-yellow hues and is characterized by elevated concentrations of manganese (1.2–2.1wt%) and iron (0.8–1.4wt%) oxides. The absorbance spectra were measured for three samples of this group, two of a light brown-yellow hue and one a dark brown fragment (S2 and Figs. 3 and 6). The light-yellow samples (#030 and #032) show a weak shoulder at 380nm and 420nm of Fe3+ causing the yellow tinge. The fact that these glasses have above 1.5wt% manganese and no Mn3+ band around 500nm means that manganese is in its colourless Mn2+ state [59,60]. In the case of the dark brown samples the spectrum was saturated and no conclusive information was obtained.

The red and olive-green samples have iron contents higher than 2.9wt%. The red samples #019 and #026 have high contents of copper (1wt%) and some lead oxides (0.9% and 0.1wt%, respectively). According to the literature high Cu and Pb are necessary in the creation of an opaque red colour [61–63]. In the visible range, sample #019 shows saturation below 580nm and further investigation is require to understand the chromophores of this sample. Green samples #031, #039, and #051, and turquoise opaque sample #003, have a combination of Cu >0.9wt% and Fe >0.6wt%. The bright emerald green decoration on sample #001 (outlier) has additional lead [64,65]. Absorbance spectra of samples #001 and #031 show a broad absorption band in the 700–900nm region, typical of Cu2+ green-coloured glass.

Deep blue samples are attributed to the presence of cobalt. Finally, samples #002 (white opaque) and #003 (turquoise opaque) have high contents of SnO2 (about 5wt%) and PbO (20wt% and 16wt%). With a ratio of Pb/Sn >3.5 (Table 3 S1), the production of these two glasses might be associated with deliberate use of a lead-tin-calx combined with an alkali frit that ultimately led to the precipitation of tin oxide crystals [66].

Recycling indicatorsStudies on recycling practices where glass is described as colourless or naturally coloured suggest that values above 100ppm of lead, 20ppm of tin, 30ppm of antimony, 100ppm of copper are above its natural occurrence in the raw materials and are linked to recycling practices, where coloured or opacified glass is incorporated into the batch [67–69]. The Levantine (#040) and Mesopotamian (#041) plant-ash and the Egyptian (#013) samples exhibit no clear sign of recycling. The weakly coloured samples of Group 2 generally contain little lead (20–350ppm, with two exceptions at approximately 3200ppm), negligible antimony (below 2ppm), and tin values around 111ppm, thus showing little evidence of recycling.

On the other hand, all samples of Group 1 show concentrations of lead in excess of 100ppm as well as elevated copper, tin and antimony, indicating some degree of recycling (Table 3 S1). The strong correlation between tin and lead in the non-opacified samples, with a Pb/Sn ratio of approximately 4.3 (Table 3 S1), matches that of tin-opacified samples #002 and #003. This suggests contamination of the glass batch by opaque glass. However, the high antimony content correlates only with lead, indicating that Sb traces might come from another lead-related contaminant, such as high lead glass or lead-related processes. All this points to a complex production process with contamination from multiple sources.

DiscussionA clear correlation between the chronology and specific compositional groups is not evident in the Silves assemblage (Table 1). While Groups 1a and 1b occur in both 11th- and 12th- to mid-13th-century contexts and Group 2 appears exclusively during the 12th to mid-13th centuries, the trace-elements signature of Group 2 aligns more closely with earlier material. The limited number of analysable samples of early contexts also prevents a more detailed exploration of the temporal patterns. Most compositional groups do not belong exclusively to a single chronological phase, a phenomenon observed at other sites such as Ciudad de Vascos [13] and Mértola (unpublished data). Accordingly, these groups are treated primarily as indicators of different recipes and by extension origins, rather than as chronological markers. Presenting all 49 analyses together offers a view of long-lived productions and exchange dynamics.

Silves groups within the Iberian glass mapThe assemblage of Silves fits what is expected from its chronological and geographical context, in terms of flux used. To uncover possible compositional relationships and thus possible origins of the glass from Silves, the data was compared with other contemporary sites in al-Andalus. The earliest Islamic glass workshop analysed in the Iberian Peninsula, the 12th-century Puxmarina workshop in Murcia (Spain), provides evidence of the production of soda-rich plant-ash glass in the form of drops, threads, and crucible remains, as well as the presence of Iberian soda-ash lead glass. The composition of the Puxmarina glass is inconsistent with that of other Mediterranean glasses, including Levantine and Egyptian [16]. And due to the high correlation coefficient between titanium and aluminium of all samples, it was hypothesized that Puxmarina was a primary production centre with a single silica source [3,15,16].

The TiO2/Al2O3 against Al2O3/SiO2 (Fig. 6a) ratios of Group 1 from Silves fall within the range delimited by the glass samples from Puxmarina. However, the range appears to be split into two. Group 1a, along with seven Puxmarina samples have lower Al2O3/SiO2 ratios (<0.05), while the remaining samples of Puxmarina show similar values to Groups 1b and 2, with Al2O3/SiO2 ratios above 0.05. Assuming that Puxmarina exploited a single silica source, the wide range of Al2O3/SiO2 values seem to be characteristic of that silica source. Variations of alumina content have been reported in alluvial sand deposits [56,70].

Comparison of Silves plant-ash glass and soda-rich lead glass with data from 10th-century Córdoba [11,44], 12th-century workshop of Puxmarina, Murcia [64], the Iberian glass from Ciudad de Vascos [13]. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) TiO2/Al2O3 versus Al2O3/SiO2. (b) Iron oxide versus manganese oxides.

A similar wide range of alumina concentrations was observed in the glass from Ciudad de Vascos (Spain) dating between the 10th and 12th centuries [13]. The glass from Ciudad de Vascos represents the largest Islamic glass assemblage in the Iberian Peninsula analysed to date and reveals the emergence of new soda-rich plant-ash glass groups. Sr and Nd isotopic analysis has confirmed that one of these groups, Vascos 4, is probably of Iberian origin [3]. The TiO2/Al2O3 and Al2O3/SiO2 ratios of the majority of Vascos 4 are consistent with Group 1b (Fig. 6a) and Puxmarina with Al2O3/SiO2 ratios above 0.05 (Fig. 6).

Regarding the iron content, another element usually associated with sand, Groups 1a and 1b have on average higher iron concentrations than Vascos 4 and Puxmarina glass (Fig. 6b). The elevated iron in Group 1b, could be explained by the presence of significant higher Mn contents. Based on the TiO2/Al2O3 ratios and iron concentrations, Puxmarina cannot be excluded as a possible workshop of origin or a similar sand source for Silves Group 1. Since no trace elements data are available in Puxmarina, possible conclusions are limited. Silves Group 1b clearly shows similarities with Vascos 4 in terms of major, minor and trace elements (see below). Finally, in the case of Group 2, although its Al2O3/SiO2 ratios and iron contents are similar to Puxmarina and Vascos 4, the TiO2/Al2O3 ratios are much higher (Fig. 6). Group 2 appears closer to some 10th-century plant-ash samples from Córdoba, specifically glass from Piscinas Municipales [44] and the Rabad of Šaqunda [11] (Fig. 6a).

Technological overlapIt is not surprising to find Iberian soda-ash lead glass in Silves as this type of glass has been found in the glass records of 10th- to 11th-century in Córdoba [15,44], Pechina (Almería) [3], Ciudad de Vascos [13], and 12th-century Puxmarina [16]. The appearance of Iberian glass with high lead content can be traced back to Šaqunda (Córdoba) at the beginning of the 9th-century and for which lead from the mining districts north of Córdoba was used [11]. The isotopic analysis of samples #010 and #012 show that the lead probably came from the same mining area (Pedroches or Linares-La Carolina) as other soda-rich lead glass from Córdoba [44] and Vascos [3]. The fact that the chemical patterns of silica-related elements observed in soda-rich lead glass are similar to those of Group 1a (Figs. 3b, 5a and 6), suggests commonalities in the raw materials of the two glassmaking techniques.

Silves within the wider Mediterranean contextThe possible origin of the Silves glass can be clarified to some extent by a process of elimination by looking at the trace element patterns. For example, the glass from Silves differs considerably from Egyptian, Levantine and Mesopotamian soda-rich plant-ash glass of similar time range, in terms of lithium, boron, thorium and REE concentrations (Fig. 7). The Silves groups have higher lithium levels than those typically encountered in Egyptian [7] and Levantine [13,19] glass and higher boron levels than Mesopotamian plant-ash glass (Fig. 7a) [36]. This is a shared characteristic with the Iberian glass from Vascos. Given the volatility of lithium, these differences point to variations in glassmaking techniques [71], whereas differences in boron may be due to the use of different raw materials in the flux [72] or in the silica source [73]. These elements have been used as markers to distinguish Iberian from Near Eastern compositional groups [13].

Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) B/Na2O and Li/Na2O ratios reflect differences in the fluxing agent. (b) Th/Zr versus La/TiO2 and Ce/Zr show differences in the silica source.

Data sources: the Iberian groups (Vascos 4 and soda-rich lead) of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36].

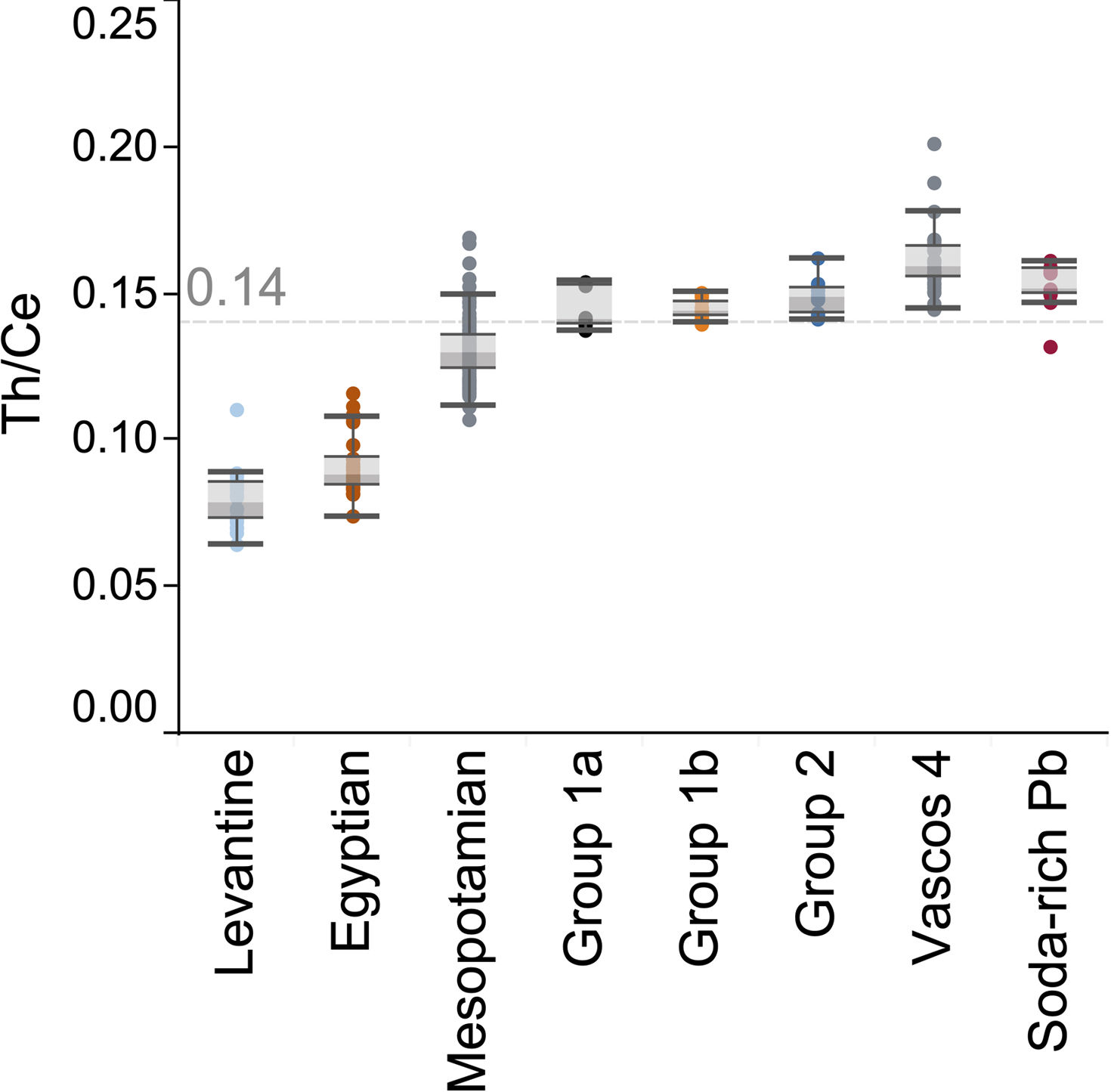

The most significant differences that distinguish Iberian glass, including Silves, from all others are in elements related to the silica source such as thorium, and REEs but also zirconium and titanium (Fig. 7b). The ratios between Ti2O and Zr (related to heavy minerals like zircon, rutile, ilmenite) versus Th and REE (related to monazite and xenotime) [41] reflect the specific minerals proportion in the silica source. First, the Levantine and Mesopotamian values of La/TiO2 tend to be much higher than in glass from other regions including the Iberian Peninsula. Iberian plant-ash glass in general, and the samples from Silves Group 1 in particular, have significantly higher Th/Zr ratios than Levantine, Egyptian or Mesopotamian glass (Fig. 7b). The Th/Ce ratios also reflect a difference in the mineral species characteristic of silica sources of different regions [74,75]. Silves Group 1 and Vascos 4 from Near Eastern glass have higher Th/Ce (>0.14; Fig. 8); while Levantine, Egyptian and Mesopotamian glass tend to have low Th/Ce ratios (<0.13). Thorium, Ce and La are concentrated in sands with minerals like monazite [41,76]. These sands are often found in placer deposits, commonly located in coastal and fluvial environments. There are a number places in the Iberian Peninsula with monazite-bearing sands in the area of Almería-Málaga [74,75] that could explain the trace element characteristics of Silves Group 1.

Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. Th/Ce Boxplot, whiskers extend within 1.5 times the IQR.

Data sources: the Iberian group of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [13,19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36].

Silves Group 2 shares some key characteristics with the alleged Iberian group such as high Li/Na2O, B/Na2O and Th/Ce ratios (Figs. 7 and 8). It has lower Th/Zr ratios than other Iberian glasses, but this could be explained by its high Zr contents (Fig. 7b). In this, Group 2 shares again some similarities with the 10th-century plant-ash glass samples from Córdoba that also have high Zr contents and relatively low Th/Zr ratios [11,44] (Fig. 7). It was suggested that the glass from Córdoba was the output of an Iberian production [11]. Based on this comparison, an Iberian origin of Silves Group 2 seems likely. Interestingly, Group 2 not only shares chemical patterns with the plant-ash glass from Piscinas Municipales (Córdoba), but both have little contents of recycling indicators. This low-recycling group was found in 10th- to 11th-century contexts and perhaps can provide valuable insights into the original compositions of these materials.

Connection with the MediterraneanA special feature of the Silves collection is the proportion of East Mediterranean glass types. In the 10th- to 12th-century sites of Ciudad de Vascos and Piscinas Municipales (Córdoba) about 30–36% of the reported glass is Levantine or Egyptian, whereas in Silves there are only three samples (i.e., 6% of the total). Although this could be distorted due to the limited number of analysed samples, the relatively few imports from the Near East may point to a distinct trade pattern. Glass imports from the Eastern Mediterranean are typical for collections in the Iberian Peninsula during this period [3,13,15]. Silves’ imports show little evidence of recycling, indicating they were likely imported as finished products, perhaps brought via religions pilgrimages or as recipients of certain products (e.g., kohl), as some studies of the material of the site indicate [27]. Although this requires further research, the small proportion of import could be explained by the fact that Silves was in the western periphery of al-Andalus and the economic peak of the city came much later than the last raw glass imports registered in the 10th century [17]. By the 11th century, Iberian glass is predominant, so Near Eastern commodities no longer reached even an elite place such as Silves Castle. By the 12th century, the main external influence came from North African dynasties. When this is added to the constant looting of the city at the end of the century, it was expected to find fewer imports from the Eastern Mediterranean.

Final remarksSimilar to other Islamic sites in the Iberian Peninsula, the Silves assemblage shows overlapping compositional groups across different centuries, rather than distinct groups confined to specific chronological phases. The compositional data of the glass assemblage from Silves revealed similarities in the glass consumption patterns with other 10th to 12th-century Iberian sites such as Piscinas Municipales, Ciudad de Vascos and Puxmarina. The analytical data shows that the largest group (Group 1, n=31) appears to have most of the characteristics of what is currently defined as glass of Iberian origin (Vascos 4), with the only difference being that it has even higher Th/Zr ratios. Group 2 (n=8), exhibits characteristics of a glass type that appears in 10th-century contexts in Córdoba. This group shows little signs of recycling, and although its chemical signature is close to Group 1 and Vascos 4, it cannot be unequivocally classified as Iberian due to its lower Th/Zr ratios. However, it does not have any parallels in the Eastern Mediterranean either. Its high contents of heavy elements rather suggest an Iberian silica source that is geochemically similar but not identical to that of Group 1. This study argues that Th/Ce ratios greater than 0.14 seems to be characteristic of Iberian glass, which is observed in Vascos 4 as well as Silves Groups 1 and 2. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that Iberian soda-ash lead glass shares similar Th/Ce ratios and trace element patterns with Group 1.

Despite the fame of the city of Silves, known for its wealth, political importance, and as the home of Taifa kings, governors, and high-ranking officials, the scarcity of glass artifacts recovered from the earlier contexts is notable. This may be attributed to episodes of conflict, constant plundering and political instability, potentially contributing to material shortages. Although this may help explain the limited occurrence of glass in earlier contexts, the interpretation of the results from these layers is hampered due to the small number of samples and can only offer some indication of patterns at this stage. In 12th- to mid-13th-contexts, the number of fragments recovered had quadrupled, supporting the idea that Silves may have regained purchasing power [21,22]. This is reflected in the presence of unique goods and cosmetic containers in the archaeological record [26,27]. The predominance of glass of likely Iberian origin, with a negligible number of imports from the eastern Mediterranean compared to other Iberian sites [13,44] suggests that Silves Castle was part of a different exchange network. The city's peripheral location and changing geopolitical circumstances may have influenced these patterns.

CRediT authorship contribution statementConceptualization: A.C.I. and N.S.; data curation: A.C.I. and N.S.; formal analysis: A.C.I. and N.S.; investigation: A.C.I. and N.S.; resources: A.C.I., R.V.G., M.V. and N.S.; supervision: A.C.I., M.V. and N.S.; visualization: A.C.I. and R.V.G.; writing – original draft: A.C.I. and N.S.; writing – review & editing: A.C.I., R.V.G., M.V. and N.S.

FundingFunding has been provided by the Fundacão para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) scholarship 2022.12919.BD. The work was carried out at IRAMAT-CEB, UMR7065 (CNRS) and at the VICARTE Research Unit (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00729/2020 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/00729/2020).

![Silves glass compared to 9th- to 12th-century Islamic glass of Egyptian [7], Mesopotamian [36], Levantine [7,13] and Iberian [13] origins. Ternary plot of Na2O, CaO and K2O+MgO showing the classification of glass according to the fluxing agent [35]. Silves glass compared to 9th- to 12th-century Islamic glass of Egyptian [7], Mesopotamian [36], Levantine [7,13] and Iberian [13] origins. Ternary plot of Na2O, CaO and K2O+MgO showing the classification of glass according to the fluxing agent [35].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Base glass characteristics of the glass from Silves. (a) Titanium versus aluminium oxide displaying all samples distinguishing Groups 1a, 1b, 2, soda-rich Pb and outliers. (b) Average of trace elements and REE patterns of Groups 1a, 1b, 2 and soda-rich Pb, normalized to MUQ, a standard geological reference material [42]. Base glass characteristics of the glass from Silves. (a) Titanium versus aluminium oxide displaying all samples distinguishing Groups 1a, 1b, 2, soda-rich Pb and outliers. (b) Average of trace elements and REE patterns of Groups 1a, 1b, 2 and soda-rich Pb, normalized to MUQ, a standard geological reference material [42].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Comparison of lead isotopes of Silves high lead glass with different mining areas in Spain. (a) 208Pb/204Pb versus 207Pb/204Pb; (b) 207Pb/206Pb versus 208Pb/206Pb. Data sources: Linares-La Carolina (Jaén), Los Pedroches (Córdoba) and [45], Alcudia Valley (Ciudad Real); Iberian Pyrite Belt [46]. Comparison of lead isotopes of Silves high lead glass with different mining areas in Spain. (a) 208Pb/204Pb versus 207Pb/204Pb; (b) 207Pb/206Pb versus 208Pb/206Pb. Data sources: Linares-La Carolina (Jaén), Los Pedroches (Córdoba) and [45], Alcudia Valley (Ciudad Real); Iberian Pyrite Belt [46].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr5.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Comparison of Silves plant-ash glass and soda-rich lead glass with data from 10th-century Córdoba [11,44], 12th-century workshop of Puxmarina, Murcia [64], the Iberian glass from Ciudad de Vascos [13]. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) TiO2/Al2O3 versus Al2O3/SiO2. (b) Iron oxide versus manganese oxides. Comparison of Silves plant-ash glass and soda-rich lead glass with data from 10th-century Córdoba [11,44], 12th-century workshop of Puxmarina, Murcia [64], the Iberian glass from Ciudad de Vascos [13]. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) TiO2/Al2O3 versus Al2O3/SiO2. (b) Iron oxide versus manganese oxides.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr6.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) B/Na2O and Li/Na2O ratios reflect differences in the fluxing agent. (b) Th/Zr versus La/TiO2 and Ce/Zr show differences in the silica source. Data sources: the Iberian groups (Vascos 4 and soda-rich lead) of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36]. Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. All soda-rich lead glasses from the different sites are shown in red. (a) B/Na2O and Li/Na2O ratios reflect differences in the fluxing agent. (b) Th/Zr versus La/TiO2 and Ce/Zr show differences in the silica source. Data sources: the Iberian groups (Vascos 4 and soda-rich lead) of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr7.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. Th/Ce Boxplot, whiskers extend within 1.5 times the IQR. Data sources: the Iberian group of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [13,19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36]. Comparison of the Silves glass with reference groups. Th/Ce Boxplot, whiskers extend within 1.5 times the IQR. Data sources: the Iberian group of Ciudad de Vascos [13], Levantine [13,19], Egyptian plant-ash dated to 10th century [7] and Mesopotamian (Samarra 1 and 2) from the 9th century [36].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000005/v1_202510290728/S0366317525000433/v1_202510290728/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr8.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)