Raw clay has been an essential material for thousands of years, valued for its distinctive properties and versatility, particularly in ceramic production. Thus, this study seeks to systematically classify raw clays based on their suitability for manufacturing ceramic building materials. Key indicators such as 0.063mm sieve residue and chemical composition were evaluated to enable a preliminary and rapid assessment. The 50 raw clays from Serbia were grouped using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) according to compositional similarities, and these classifications were subsequently compared against industrial samples. Further analysis through mineralogical composition and behavior during heating within these groups provided a comprehensive understanding of their physical behavior. The results demonstrate that PCA effectively distinguishes raw clays based on their chemical composition, paving the way for a reliable classification for ceramic production. This system enables manufacturers to optimize materials for diverse applications, including common bricks and blocks, roof tiles and clay ceilings, ceramic tiles, and refractory products. Key findings reveal that raw clays containing 15–20% Al2O3, 3–9% Fe2O3, and at least 2% fluxing oxides are well-suited for heavy clay products. For ceramic tile production, optimal clay batches should contain no more than 1.5% Fe2O3, 1.0% TiO2, and less than 0.2% organic carbon. Meanwhile, refractory clays must exhibit a minimum of 15–20% and up to over 42% Al2O3, with constraints on SiO2 (below 76%), Fe2O3 (3.7%), Na2O and K2O (3.7%), and CaO (1.0%) after firing. Through this classification framework, manufacturers can more effectively select and refine raw clays to meet the stringent demands of ceramic production, ensuring both efficiency and performance in industrial applications.

La arcilla cruda ha sido un material esencial durante miles de años, valorado por sus propiedades distintivas y su versatilidad, especialmente en la producción de cerámica. Por ello, este estudio busca clasificar sistemáticamente las arcillas crudas según su idoneidad para la fabricación de materiales cerámicos de construcción. Se evaluaron indicadores clave, como el residuo del tamiz de 0,063mm y la composición química, para permitir una evaluación preliminar y rápida. Las 50 arcillas crudas de Serbia fueron agrupadas mediante Análisis de Componentes Principales (PCA) según similitudes composicionales, y estas clasificaciones se compararon con muestras industriales. Un análisis adicional de la composición mineralógica y el comportamiento térmico dentro de estos grupos proporcionó una comprensión detallada de sus propiedades físicas. Los resultados muestran que el PCA distingue eficazmente las arcillas crudas según su composición química, lo que permite establecer un sistema de clasificación fiable para la producción cerámica. Este sistema ayuda a los fabricantes a optimizar materiales para diversas aplicaciones, incluidas ladrillos y bloques comunes, tejas y cielorrasos de arcilla, baldosas cerámicas y productos refractarios. Los hallazgos clave revelan que las arcillas crudas con 15-20% de Al2O3, 3-9% de Fe2O3 y al menos 2% de óxidos fundentes son adecuadas para productos de arcilla pesada. Para la producción de baldosas cerámicas, los lotes óptimos deben contener un máximo de 1,5% de Fe2O3, 1,0% de TiO2 y menos de 0,2% de carbono orgánico. Por otro lado, las arcillas refractarias deben tener entre 15 y más de 42% de Al2O3, con restricciones en SiO2 (por debajo del 76%), Fe2O3 (3,7%), Na2O y K2O (3,7%), y CaO (1,0%) después de la cocción. Gracias a este marco de clasificación, los fabricantes pueden seleccionar y refinar las arcillas crudas con mayor precisión para satisfacer los exigentes requisitos de la producción cerámica, garantizando eficiencia y rendimiento en aplicaciones industriales.

Despite global efforts to reduce raw material consumption, minimize waste, and enhance energy efficiency—especially in lowering the construction industry's CO2 footprint—human activities often counteract these gains [1]. In Serbia, the discovery of jadarite has fueled international interest in lithium and boron extraction for electric car batteries, but this mining poses severe environmental risks [2]. It threatens ecosystems, underground water resources, and air quality in Serbia and beyond. These potential environmental impacts are particularly concerning as the affected areas are rich in high-quality stoneware clays. Clay-rich sediments tend to absorb heavy metals [3]. Soil and water contamination could endanger worker safety and compromise valuable clay deposits. Local scientists are committed to safeguarding natural resources and developing sustainable solutions, striving to harmonize industrial advancement with environmental stewardship.

Despite centuries of research, clays remain challenging due to their heterogeneous composition and texture, complicating their optimization for geotechnical and industrial applications [4,5]. Raw clays rarely occur as single minerals—kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite often coexist with chlorite, mixed-layer clays, and non-clay minerals like quartz, feldspars, and carbonates. Their chemical and mineralogical properties, with granulometry, dictate their suitability for different uses. Kaolinite is prized for high-quality ceramics, refractories, and cement [6,7]. Illite, with kaolinite and montmorillonite, is used in wall tiles and heavy-clay products [8–10], while quartz sand or calcite may be added to adjust plasticity and firing properties [11].

Heavy clay products require materials with lower clay content to produce fired bricks and blocks meeting EN standards. These norms define compressive strength and water absorption requirements, ensuring product consistency [12–14]. Ceramic tile standards focus on dimensions, surface quality, wear resistance, and chemical durability. However, industrial ceramic tiles most frequently fail to meet standard specifications, especially in water absorption (ranging from 0% to over 10%) and modulus of rupture (12MPa to over 32MPa) [15]. This study accounts for these critical factors to ensure compliance with industry norms.

Particle size distribution is a quick but limited method for assessing raw clay suitability [16–19]. A uniform clay fraction across silt and sand-sized particles enhances dry strength but depends on shaping and water content. It also influences reactions during firing and final porosity [20]. Plasticity determines whether raw or mixed clays require additives for ceramics [21,22]. Mineralogical composition guides clay applications, distinguishing structural products from roofing tiles via a triaxial quartz, feldspar, clay mineral, and carbonate graph [23]. Fluxing agents affect firing temperature and quality [24,25], while the Al2O3/SiO2 ratio estimates clay mineral presence. Fe2O3 content influences color and suitability—higher levels favor heavy clay products or wall tiles with ≥10% water absorption [8,26]. Red clay can produce red-body tiles with 2–3% water absorption but lacks sufficient flexural strength [15,27]. Despite ternary diagrams aiding classification, precise characterization remains challenging [18,19,23].

Modern analyses prioritize speed and cost-efficiency. Traditional silicate analysis determines the chemical composition, but X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) now offers faster, more reliable results, though accuracy depends on the instrument, sample granulometry, and preparation [3,28]. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) increasingly provides bulk mineralogical analysis without requiring oriented and heated samples [25,29], relying on semiquantitative phase analysis. Rapid, reliable assessments are crucial for sustainable raw material evaluation.

New deposits require material passing a 0.063mm sieve to stay below 20%, with ceramic tile compositions limited to 1.3–1.5% Fe2O3 and 1.0% TiO2. Pale coloration results from lower Fe2O3 and TiO2 content, while reddish tones indicate higher levels [7,26]. Porcelain tile batches should contain less than 0.2% organic carbon. For refractory clays, fired content must not exceed 76% SiO2, 3.7% Fe2O3, 3.7% Na2O and K2O, and 1.0% CaO. Low-grade refractory clays require at least 15–20% Al2O3, while the most fire-resistant types exceed 42% Al2O3 and TiO2[30]. Raw clays with 15–20% Al2O3 and 3–9% Fe2O3 suit heavy clay ceramics [31–33], though 10% Al2O3 can be acceptable [16]. Fluxing oxides (Na2O, K2O, CaO, MgO) should be at least 2% [33], with higher Al2O3 and Fe2O3 levels needed for roofing tiles [16].

The primary objective of this study is to rapidly classify raw clays based on their suitability for traditional ceramic applications:

Phase One: This involved compositional analysis of various raw clays, followed by descriptive statistical evaluations including Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test, Pearson's correlations, and Principal Components Analysis (PCA). After identifying the four groups of raw clays and their potential applications, another set of industry-used samples was implemented to confirm the PCA grouping results.

Phase Two: The groups and their designations are assessed using 8 raw clays as a benchmark for the best-suited types of ceramic products. Tests are conducted on water absorption and mechanical strength.

Phase Three: This phase focused on examining the mineralogical differences and behavior during the firing of clays grouped into four categories based on PCA results. The clays were classified according to their suitability for producing ceramic tiles, common bricks and blocks, roofing tiles, and refractory tiles. The behavior during heating is followed by changes in dimensions, energy flow and mass.

This approach allowed the effective categorization of clays based on their chemical composition and characteristics during heating.

Materials and methodsThe deposits in the Balkans that entered this study were sampled at different locations: Batulovce (BA), Beočin (BE1 and BE2), Bijeljina (BI1 and BI2), Čurug (CU1 and CU2), Kanjiža (KNJ), Kaštavar (KA), Kikinda (KI1–KI4), Resinac Belogoš (RB1–RB3), Stražilovo (S1 and S2), Toplička Mala Plana (TMP), Metriš (M1–M6), Gornje Crniljevo (GC1–GC6), Dimitrovgrad (D1–D9), Damnjanovića brdo – sever (DBS1–DBS9), and Savići (SA). The samples are analyzed as a possible single component to produce various kinds of ceramics. All 50 samples were collected between 2020 and 2024.

Raw samples were dried at 105°C and then analyzed in triplicate for the chemical content of major oxides using an energy-dispersive XRF analysis, compared to suitable certified reference materials [3]. The chemical composition was analyzed under vacuum conditions using the ED-XRF technique with the Spectro Xepos instrument, equipped with a 50W/60kV X-ray tube. The reference materials used for calibration verification and method validation were CRM-07402, CRM-07427, CRM-07428, CRM-07430, CRM-2709, CRM-2710, NCS DC 60102, NCS DC 60104, NCS DC 60105, and NCS DC 60106.

Qualitative mineralogical analysis was carried out on the powder bulk samples in triplicate using a powder diffractometer Philips PW-1050, which uses a Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation with a wavelength of λ=1.54178Å and a Cu X-ray tube. The raw clays were ground using a planetary mill, with the fraction below 0.5mm being selected for analysis. The sample preparation involved a standard procedure of placing the powder in an appropriate carrier and aligning it with the focal plane of the goniometer. The scanning speed of 0.05°/s without a monochromator was employed. A semi-quantitative reference normalized intensity ratio methodology is used to reveal the concentration of the identified phases. This involves calculating the relative percentages of each phase based on their respective contributions to the sum [25,34]. The concentration of the absolute phase is also determined based on the XRF data [29]. The percentages representing the mineral concentrations are adjusted to add up to 100%.

Chemical composition and XRD quantitative analysis results are preliminarily tested by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's HSD test to check if the database contains statistically significant differences between the samples and prove the results are appropriate for further statistical investigation. Pearson's correlations were also determined [35].

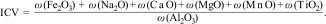

Chemical composition is also used to evaluate the sediment maturity based on the Index of Compositional Variability – ICV [36–38], Eq. (1):

The ICV is also a useful parameter to test the provenance of sediments and is important in geological studies [39]. Higher ICV values (>1) are found in nonclay silicates like feldspars and suggest a low presence of clay minerals in the sediments, while pointing to initial deposition in active tectonic settings and belonging to first-cycle sedimentation deposits. On the other hand, ICV values less than 1 are associated with alteration products (clay minerals), indicating a secondary sediment maturation in a passive tectonic environment or first-cycle sedimentation under conditions of high weathering. Lower ICV is found in montmorillonite as compared to illite and later also in the kaolinite group [36,38].

While the ICV was previously applied to geological studies, this is the first study to use it for comparing multiple deposits of raw clays aimed at producing traditional ceramics. The obtained results led to meaningful and well-supported conclusions.

The particle size distribution was tested after crushing with no further disturbing of the samples. Dry sieving through standard sieves was employed to identify silt and sand-sized particle quantities. The size distribution of particles less than 0.063mm was determined with the hydrometer method, utilizing a sodium hexametaphosphate solution as the dispersant. The results showed that most of the samples did not belong to any of the heavy clay products as defined by Winkler (Table A1). After milling of the samples, as described above, remains on the 0.063mm are determined using the wet method (Table A1).

The multivariate analysis is selected to analyze the results. Cluster analysis presents only one coordinate (the first principal component), and it does not analyze a significant part of the variance of the system. Thus, the PCA is considered more precise [40]. The PCA is a method used in this study to break down the original data matrix into loading (representing different raw clay samples) and score (based on chemical and mineralogical content) matrices through a series of multiplications [35,41]. This approach was employed to group the studied raw materials according to their compositional similarities. Subsequent analyses were conducted based on the identified groups. After grouping the raw clays and considering their potential application in various traditional ceramic products, a set of industrially used samples was implemented to test the PCA results. All statistical tests were carried out using Statistica 12.0 software.

Thermal instrumental methods utilized Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) with a TA Instruments SDT Q600 apparatus and dilatometry (Setaram), performed in the air atmosphere up to 1000°C and heated at a 20°C/min rate. An airflow rate of 20cm3/min was implemented. The soaking time in the dilatometer was 1h.

Another set of clays is introduced as the test group to evaluate the conclusions obtained. The samples from Savića Mala are employed in the ceramic tile production batches (SM1 and SM2), Batulovce and Kikinda are used in roof tile and clay ceiling production (BA24 and KI24), Bečej and Beočin raw clays are used in ceramic blocks (BE19 and BE20), and Dimitrovgrad clay for refractory applications (DP1 and DP2). The chemical and mineralogical composition of the test group is determined as previously described.

Upon arrival at the laboratory, raw clay samples were crushed and dried until they reached a constant mass. Heavy clay samples were ground using a wheel mill with a 1mm opening diameter. After this, the samples were moistened with sufficient water to obtain a plastic mass and left in sealed nylon bags for 24h to homogenize. Laboratory samples of hollow blocks, measuring 55.3mm×36mm×36mm, were produced through extrusion under vacuum using a Händle press. The samples were dried in the air for the first 24h, and later in a laboratory dryer until reaching a constant mass.

Raw materials suitable for ceramic tiles were ground in a ball mill until they passed through a 0.5mm sieve. Larger grains were returned to the mill to ensure all the mass was utilized. The samples (SM1, SM2, DP1, and DP2) were dry pressed with 4% distilled water in the 25mm×120mm tiles using a hydraulic press and a pressure of 400kg/cm2.

The temperature in the laboratory electric kiln was increased at a rate of 70°C/h until it reached 200°C, then at 92°C/h until 520°C. Afterward, it was raised at 60°C/h until 610°C, and finally, the rate was adjusted to 140°C/h until the target temperature was reached. The soaking time was 1h. Water absorption and mechanical strength are tested after firing at 870°C to 1250°C. The selected firing regime was intentionally slow to ensure a thorough sintering process. This approach allowed the reactions that cause volume changes to be maintained at the target temperature long enough for completion, thereby preventing any cracking [20].

The water absorption of the raw clays BA24, KI24, BE19, and BE20 was assessed by soaking samples in cold water for 24h [14]. The compressive strength was determined using Alfred Amsler's hydraulic machine, with the average strength calculated based on three samples. The results indicated complete failure of the samples, as required by the standard [13].

The water absorption of the products based on the samples aimed for ceramic tiles and refractory ceramics (SM1, SM2, DP1, and DP2) is determined in boiling water [42] and the modulus of rupture using the three supports test using the Crometro CR4/E1 Gabrielli machine [43].

Results and discussionChemical and mineralogical compositionThe chemical composition of the 50 studied raw clays is presented in Table 1 and Table A2 in the Appendix. The results show significant variations among the main oxides (SiO2, Al2O3 and Fe2O3) and loss on ignition. The contents of SiO2 in some of the red clay samples are close to the boundary of 70% [44]. The alteration in the presence of earth and alkaline earth oxides (fluxes) is also notable. These differences are also evident when studying semi-quantitative mineralogical compositions (Table 2 and Table A3). The primary phases identified in variable amounts are quartz, illite/muscovite, and kaolinite. The chemical and mineralogical compositions of the samples were compared using the post hoc Tukey HSD test, and statistically significant differences at the p<0.05 level were identified.

Chemical composition variations.

| LOI (%) | SiO2 (%) | Al2O3 (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | CaO (%) | MgO (%) | Na2O (%) | K2O (%) | SO3 (%) | P2O5 (%) | MnO (%) | TiO2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mina | 2.65 | 39.93 | 11.40 | 1.05 | 0.15 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| Max | 19.94 | 69.76 | 28.17 | 8.80 | 15.53 | 7.41 | 1.92 | 4.14 | 1.92 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 1.18 |

| Avr. | 9.13 | 57.58 | 20.10 | 3.86 | 2.68 | 2.59 | 0.61 | 2.38 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.80 |

| SD | 4.47 | 8.30 | 4.74 | 2.33 | 3.89 | 1.87 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

Mineralogical composition variations.

| Q (%) | I/M (%) | K (%) | Sm (%) | Ch (%) | F (%) | H (%) | C (%) | Py (%) | Rt (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mina | 19.40 | 10.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| Max | 59.70 | 57.40 | 44.00 | 9.60 | 9.10 | 27.50 | 4.50 | 27.20 | 1.90 | 3.20 |

| Avr. | 38.82 | 27.57 | 14.87 | 1.56 | 1.66 | 7.64 | 1.99 | 3.92 | 0.04 | 1.93 |

| SD | 9.82 | 10.38 | 11.16 | 1.82 | 2.57 | 7.70 | 1.26 | 6.96 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

The ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's HSD test were applied collectively to all samples and deposits, identifying groups of statistically similar samples based on their chemical composition (Appendix Tables A1 and A2). For instance, within samples M1–M6, M1 and M2, as well as M2–M6, showed chemical similarity. Despite these overlaps, the PCA (Principal Component Analysis) graph revealed a clear visual separation of sample clusters, reflecting their overall chemical variability (see Chapter 3). DBS and GC deposits showed the highest chemical similarity, as confirmed both by the PCA and the HSD test. DBS samples were more internally consistent than GC samples. However, key oxide contents (e.g., SiO2: ≈64–68%, Al2O3: 20.2–22.7%) showed sufficient variation to support the robustness of the classification provided by the database. Thus, it is considered justified to treat different samples from the same deposit as separate entities in further analysis.

Pearson's correlationsA correlation study of the chemical and mineralogical compositions was conducted to gain deeper insights into the data. Strong, statistically significant correlations are obtained, thus proving the linear relationships among the parameters (Tables 3 and 4, and Table A4). Loss on ignition (LOI) is predominantly linked to carbonates, as indicated by statistically significant positive correlations with CaO and MgO. However, a part of the LOI is owed to organic matter. Higher LOI is associated with lower levels of quartz, evidenced by a significant negative correlation with SiO2, and no correlation to Al2O3 (Table A4). Furthermore, higher Al2O3 content is associated with higher levels of primarily kaolinite. Significant negative correlations exist between Al2O3 and both MgO and Fe2O3, with an insignificant correlation with K2O. The strongest correlations observed are between LOI and SiO2 (negative) and Fe2O3 and MnO (positive). Partly unexpected, different from other studies [45], insignificant correlations among quartz/Al2O3 and SiO2/Al2O3 are seen (Table 4, Table A4) that reflect many raw clays that contain low contents of clay minerals. However, Q is determined statistically significantly and negatively correlated to K mineral only (Table 4). A negative correlation between Fe2O3 and Al2O3 suggested that iron was mostly not present within the clay minerals’ structure but in the form of free Fe2O3 or Fe(OH)3[26,45]. The positive correlation between Fe2O3 and LOI [45] suggests that iron oxides and oxyhydroxides are found in the samples (see Figs. 4-7 in Section 3.4 and the DTA curves).

The most notable statistically significant correlations involve feldspar (F): there is a positive correlation between F and chlorites (Ch), and a negative one between F and kaolinite (K). Consequently, feldspars were found alongside chlorites in the studied deposits, whereas their presence was mutually exclusive with kaolinite. Ch and F exhibited a strong positive correlation, attributed to their positive associations with MgO and Na2O (Table 3). Strong statistically significant negative correlations are determined further for the pairs Ch and illite/muscovite (I/M) and F and I/M. Also, a significant positive relation is detected between hematite (H) and Ch, showing their mutual appearance. Sm and F showed a strong positive correlation, due to the CaO, MgO, and Na2O correlation. A decreased presence of illite/muscovite (I/M) was associated with increased quantities of most other minerals, including chlorite, feldspar, carbonates, and smectite (Sm). Significant positive correlations between carbonates and chlorite, and carbonates and feldspars are found. Samples with higher levels of hematite and kaolinite typically exhibited lower levels of quartz.

Principal Components Analysis (PCA)The analysis of similarities in the chemical and mineralogical compositions of the raw clays was further explored using PCA. Kaiser's criterion [46] was applied to select the factors needed for accurate classification, allowing only principal components with Eigenvalues>1. PCA indicated that the data could be effectively analyzed using the first two principal factors. When the chemical composition is analyzed (Fig. 1), Factor 1, which accounts for 61.2% of the common variance, is primarily influenced by SiO2, LOI, Al2O3, and K2O levels. Factor 2, explaining 8.4% of the variability, is associated with P2O5, Na2O, MgO, and CaO. Due to the heterogeneity of the deposits (Tables A2 and A3 in the Appendix), ANOVA analysis and HSD test, it is concluded that different samples from the same deposit can be used in further analysis and classification. However, certain similarities exist between the samples, as evident in the PCA graph, as they are closely clustered in factor space, and vice versa.

Regarding mineralogical composition, the PCA can explain 37.9% (Factor 1) and 16.02% (Factor 2). On the contrary, by comparing the cumulative variability explained by the two factors, chemical composition accounts for 69.6%, while mineralogical composition accounts for 53.9%. This suggests that the chemical composition analysis provides a more robust evaluation. Therefore, further analysis focused on the PCA of the chemical composition, which aligned with the findings of the ICV [36,37,39].

The positions of vectors and samples in PCA analysis are dependent on the specific dataset being tested. Therefore, adding various raw clays could change the main components, the clustering of samples, and their locations on the graph. Ultimately, the groups would still form in different positions. However, using the PCA is still useful for identifying similarities and distinguishing between groups in any related dataset. If other raw clays were tested, conclusions about their suitability for ceramic products might differ. Nonetheless, PCA is anticipated to reliably differentiate major ceramic product categories across various datasets. For a more precise mineralogical analysis, future studies could focus on mineral composition to refine the findings. In this study, chemical analysis provided more reliable grouping through PCA.

Quadrant I (QI) includes samples with high clay mineral content, classified as geologically and compositionally mature based on their ICV values, which ranged from 0.30 to 0.76, with an average of 0.36, which indicates the presence of clayey sediments. The highest coarse fraction contents (Table A2) after crushing and milling were determined for this group. These samples, primarily from DBS and GC deposits, contained high levels of SiO2, Al2O3, and K2O. The Al2O3/SiO2 relation varied from 0.24 to 0.40, while the sum of K2O, Na2O, CaO, MgO, MnO, and Fe2O3 was 0.05–0.11 (0.07 on average). This group is seen as the one that belongs to stoneware tiles as per Augustinik's diagram [47]. These samples, which contain substantial amounts of quartz and clay minerals, are regarded as valuable for the ceramic tile industry. However, the levels of quartz and kaolinite in these samples surpassed the previously established maximum thresholds of 40% and 20%, respectively [48]. Additionally, the quantities of detected feldspars are suitable for wall tiles (>0%) and lower (<20%) than the previously defined for wall and floor tiles, respectively [48].

This group showed lower concentrations of Fe2O3 than typically required for common bricks and blocks, roofing tiles, and extruded tiles [16]. An exception is the BI2 sample, located on the boundary between Quadrants I and II. This sample might be more suited for Quadrant II, as it is considered appropriate for brick production [16]. With Na2O contents ranging between 0.2 and 0.8%, these samples are expected to produce some of the mechanically strongest products [49].

The samples that belong to Quadrant II (QII) had ICV values between 0.62 and 1.41. Thus, QII includes raw clays that exhibit insufficient geological maturity (e.g., BE1, KNJ, KI1, KI2, KI4, RB2, RB3, S2, and TMP) as well as partially mature samples (e.g., BA, BI1, KA, KI3, and M3–M6). These clays are deemed unsuitable for high-quality ceramic tile production due to their high Fe2O3 content and the presence of carbonates (Fig. 1a) [50]. The Al2O3/SiO2 was 0.23–0.47, and the sum of K2O, Na2O, CaO, MgO, MnO, and Fe2O3 was 0.12–0.21 (0.17 on average). The samples belong to common bricks, hollow bricks, and ceramic tiles raw materials [47] defined by Augustinik's diagram due to the somewhat lower Al2O3 contents compared to QI. However, the results are not in accordance with the results of this study. This highlights the necessity to update this graph, as the variations in other oxide contents are more sensitive than previously proposed. These raw clays are highly heterogeneous, having similar Al2O3/SiO2 as in QI, but with a higher content of fluxes, primarily Fe2O3. This group of raw clays roughly satisfies the mineral and oxide requirements for common brick production previously defined [48].

The Fe2O3 concentrations in this group are appropriate for producing common bricks, roofing tiles, and extruded tiles [16]. They are better suited as red clays for roofing and extruded tiles due to their favorable clay mineral content and low carbonate levels. However, the Na2O content—an important flux in ceramics—suggests that these materials would have lower consolidation and weaker mechanical strength if fired at lower temperatures [49]. The red-firing clays are those that contain illite and montmorillonite groups where ferric iron replaced aluminum [51], and the bond strength decreases in kaolinitic clays [52]. Besides, these clay mineral groups contain alkali and alkaline earth elements within the clay mineral lattice or as the adsorbed ions. Together with the presence of iron, the content of fluxes is relatively high, which indicates that these clays cannot be fired at high temperatures [51].

The raw clays in Quadrant III (QIII), with ICV values in the 1.45–2.57 range, are classified as compositionally immature, particularly those with ICV values of 1.8 or higher, such as RB1, CU1, and CU2. Due to high LOI values, QIII primarily contains carbonate clays suitable for heavy clay products at a relatively low firing temperature, such as 900°C [53]. The raw clays that belong to this quadrant, before milling, had the highest quantities of silt- and clay-sized fractions, while the content of the sand fraction was the lowest (Table A1). After milling, the samples have the lowest remains on the 0.063mm sieve of 5.16% on average. The ICV and granulometry indicate a high share of feldspars. Al2O3/SiO2 ranged from 0.26 to 0.32, while the sum of K2O, Na2O, CaO, MgO, MnO, and Fe2O3 varied from 0.19–0.29 (0.25 on average). According to the Augustinik graph [47]. the raw materials belonged to the common bricks and hollow blocks production. These clays, characterized by high carbonate content and hematite with low smectite (Table A3), have Fe2O3 concentrations exceeding 3% and relatively low contents of clay minerals, making them suitable only for brick production [16]. This quadrant also shows the highest LOI values and the increased contents of fluxes.

In Quadrant IV (QIV), with an ICV≤0.34 [36,37], the samples exhibit the highest clay mineral content (mostly kaolinite) and significant geological maturity. These include the D deposit samples, which have a high proportion of clay minerals and elevated LOI values. Al2O3/SiO2 was the highest from all quadrants, 0.43–0.58 (0.52 on average). The sum of K2O, Na2O, CaO, MgO, MnO, and Fe2O3 was the lowest of all samples, and ranged from 0.05 to 0.07, and thus belonged to the refractory group according to Augustinik [47]. The raw clays contain Fe2O3 ranging from 2.5 to 3.4% and have a significant kaolinite content (Table A3), making them potentially suitable for refractory applications. Additionally, the Na2O content varies between 0.3 and 0.6%, while the low average MgO content suggests that these samples are likely to produce the mechanically strongest products [49]. The refractory clays in QIV are partly similar, or even more desirable than QI raw clays in terms of kaolinite contents. However, the tested refractory clays were dark-firing and contained an unwanted quantity of iron from the ceramic tiles industry's point of view [25].

As seen during this analysis, the PCA methodology effectively distinguished between different raw clay types, enabling almost precise classification. However, to further evaluate the discrimination of the raw clays obtained by the PCA, another set of 8 samples was included to test the results. The selected samples were the ones that are known as used in the factories for various applications: samples from Savića Mala are employed in the ceramic tiles production batches (SM1 and SM2), Batulovce and Kikinda are used in roof tile and clay ceiling production (BA24 and KI24), Beočin clay is used in ceramic blocks (BE19 and BE20), and Dimitrovgrad clay for refractory applications (DP1 and DP2). Chemical and mineralogical compositions of these samples are included in the Appendix (Table A5). The new PCA analysis concerning chemical composition additionally proved the initial groping of the 50 samples (Fig. 2). SM2 can also be implemented in refractory materials with a relatively high Al2O3 concentration (above 24%), but it was close to the border with the QI due to the significant presence of illite/mica [51].

The chemical and mineralogical compositions of the 8 test raw clays are presented in Table A3. Furthermore, the laboratory samples’ water absorption and mechanical properties shown in Fig. 3a demonstrate that SM1, SM2, and DP1 satisfy the specifications for floor ceramic tiles when fired at or above 1200°C (refer to Annexes G and H in [15]). These samples have a modulus of rupture ≥30 and ≥35MPa, with water absorption rates ranging from 0.5 to 3%, or below 0.5%. DP2 meets Annex J at and above the same temperature with the modulus of rupture of ≥22MPa and water absorption between 3 and 6% [15]. The high Al2O3 (27.46 and 27.85%) and kaolinite contents in DP1 and DP2 (Table A5), along with relatively low shares of SiO2, Fe2O3, CaO, Na2O, and K2O, grouped them into refractory clays [30] in QIV, Fig. 2.

Most compressive strength results satisfied the >20MPa demand for severe weathering bricks [54]. The lowest compressive strength was obtained after firing at 900°C in the case of BE19 (19.84MPa), and these are classified as moderate weathering bricks [54]. The best-consolidated samples based on red clays appeared as KI24 and BA24 (QII), due to the lowest contents of carbonates and the highest share of the clay minerals. These samples are considered appropriate for roof tile and clay ceiling elements production due to their acceptable water absorption results of <18% [55]. The lowest mechanical strength and water absorption above the set 15% [54,56] is found only in the BE19 sample (QIII).

Mineralogical analysis through XRD and thermal methods in the obtained quadrantsThe results of X-ray diffraction (XRD), differential thermal analysis (DTA), and dilatometry tests for the selected samples are presented in Figs. 4–7. A summary of key observations and events during heating for all samples from each quadrant is provided in Table 5. Mineralogically, most raw clays contained quartz (Q) as the predominant mineral in QI, QII, and QIII. In QI and QII, illite/muscovite (I/M) was the second most abundant mineral. QI contained a higher content of kaolinite compared to QII (Table 5). The raw clays in QIII primarily consisted of non-plastic materials, including quartz, carbonates, feldspar, and muscovite, with minor kaolinite. QIV samples predominantly contained clay minerals, mainly kaolinite. Sm content is detected in up to 4.3% in QII, while concentrations between 3.9 and 9.6% were found in BE2, RB1, RB2, and RB3 (QIII). Many reactions were observed during heating, which will be discussed in parallel with the DTA and dilatometry analyses.

The information related to the groups of samples obtained by the PCA.

| Instrumental method | Event | QI (ceramic tiles) | QII (roofing tiles) | QIII (common bricks and blocks) | QIV (refractory tiles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XRD – average mineralogical composition (descending) | Q, I/M, K, F, Sm, Rt, Ha | Q, I/M, K, C, F, Ch, Ha | Q, I/M, C, F, K, Ch, Sm, Ha | K, Q, I/M, Rt, Ha | |

| DTA | Water loss | 60–93 and 150–350°C | 66–115 and 125–223°C | 74–92 and 136–246°C | 64–77 and 124–159°C |

| Gth decomposition | – | 223–282°C | 249–277°C | 244–289°C | |

| Organic matter decomposition | 329–374°C | 322–364°C | 203–396°C | 357–557°C | |

| Dehydroxilation of clay minerals | 497–511°C | 482–520°C | 485–556°C | 501–521°C | |

| Degradation of Ch | – | 618°C (KI1 and KI2) | – | – | |

| Decomposition of carbonates | – | 695–790°C | 725–784°C | – | |

| Crystallization of Mul, spinel and amorphous silica | 982–986°C | 925–974°C | 911–921°C | 976–1000°C | |

| Dilatometry | A mild expansion up to 200°C | 0.02 (GC6)–0.13% (SA) | 0.01 (TMP)–0.15% (M3 and KA) | 0.02 (S1)–0.19% (CU2) | −0.19 (D3)–0.27 (D1) |

| A shrinkage | Up to 224–317°C | Up to 243–337°C | Up to 242–350°C | Up to 264–275°C | |

| A near-plateau shape | – | Up to 319–502°C | Up to 264–408°C (788°C in RB1 802 in BE2) | Up to 338–843°C | |

| Constant spreading | Up to 600°C | Up to 603–696°C | Up to 611–621°C | – | |

| Accelerated expansion | From 609–626°C to 630–642°C | From 610–630°C to 634–648°C | Up to 639°C | – | |

| Spreading 600–800°C | 0.23–0.48% | Up to 0.43% | 0.01–0.39% | −0.75–−0.05% | |

| Local liquid phase formation | 856°C (M2) | 852°C (M3 and M4) | – | – | |

| Near-plateau shape (the beginning of sintering) | 882–943°C | 893–918°C | 782–803°C | 822–871°C (only D3) | |

| Cooling phase, β-α quartz transformation (shrinkage) | 0.05 (DBS2)–0.19% (SA) | 0.05 (KI2)–0.13% (BA and KA) | 0.01 (BE2 and RB1)–0.09 (S1, CU1 and CU2) | 0.05 (D3)–0.09 (D4) | |

a Q – quartz, I/M – illite/muscovite, K – kaolinite, Sm – smectite, Ch – chlorite, F – feldspars, H – hematite, C – carbonates, Rt – rutile, Gth – goethite, Mul – mullite.

At the beginning of heating, illite and smectite clays exhibit a two-step water loss. This phenomenon is indicated by endothermic peak maxima occurring at temperatures between 60–115°C (which corresponds to physically bound water) and 124–350°C (related to interlayer water) [27,57]. The adsorbed water loss caused sample expansion to around 200°C [58,59]. As an exception, some of the samples from the D deposit that belong to QIV shrink at the beginning of firing (Fig. 7) due to the highest kaolinite content (above 40%). Partly overlapping the second step of water loss, goethite decomposition occurs in all quadrants except QI. This is evidenced by an endothermic peak in the 223–289°C range and shrinkage that lasted up to 350°C.

The contraction behavior of the samples RB1 and BE2 differs significantly due to their distinct compositions (Fig. 6). A higher percentage of free silica (i.e. quartz) in BE2 before the theoretical 571°C would lead to less shrinkage during firing due to quartz expansion [20,60]. RB1, rich in carbonates (17.80%) and low in free silica, shows mild expansion during the decomposition of carbonates between 600 and 800°C, followed by slower shrinkage due to limited vitrification [61]. In contrast, BE2, with a higher feldspar content (21.80%) and an absence of carbonates, undergoes significant shrinkage at lower temperatures due to the formation of a glassy phase from alkaline fluxes, resulting in accelerated sintering. The presence of feldspars and fluxing agents in BE2 causes earlier and more pronounced shrinkage, while RB1's high carbonate content leads to initial expansion, followed by slower shrinkage. During cooling, BE2 experiences reduced thermal expansion and a more stable dilatometric curve, while RB1, with a more crystalline structure and less vitrification, shows greater thermal expansion.

An exothermic peak related to the formation of hematite is noted only in the sample KI2 at 207°C, with the wide peak appearing at low temperatures due to its weak bonds to other minerals [62].

Organic matter decomposition is observed in all samples, with peaks occurring depending on the particle sizes of this material, between 203 and 557°C. This reaction may cause shrinkage of the material due to the release of gases [63] or spreading if the gases remain trapped within the ceramic matrix [25]. In some samples from the D deposit, this decomposition is interrupted by endothermic peaks around 420°C, which are attributed to organic and maceral impurities [64].

Further dehydroxylation of clay minerals occurred between 482 and 556°C, overlapping with constant sample expansion [58], except for QIV samples. Dehydroxylation below 530°C indicates the presence of highly disordered kaolinite in most samples [7,65], while the appearance temperature can be translated to higher values by the presence of illite. Additionally, isomorphous exchange of Al by Fe cations in clay minerals like illite and chlorite is likely to decrease the temperature of the main peak in a DTA. This occurrence, which is connected to the mineral compositions of raw clay, was barely noticeable in some of the samples, if at all. Quartz particles continue to expand even after the dehydroxylation process, which prevents further constriction of the interatomic spacing in clay minerals. This phenomenon is due to the high quartz content in most samples. The characteristic accelerated expansion was absent in samples from QIV due to the low content of free quartz [20]. A further mild expansion observed roughly between 600 and 800°C is associated with quartz [7,59] and illite phase transformations [58]. This effect is also influenced by the degradation of chlorites and carbonates in QII and QIII[58]. The degree of expansion is influenced by quartz content, which aids in spreading, and clay minerals, which undergo contraction due to ongoing dehydroxylation up to 680°C [66]. During heating from 600 to 800°C, samples from QI exhibit an expansion of up to about 0.48%, indicating a more significant presence of illite compared to muscovite, as confirmed by semi-quantitative mineralogical analysis [57,67]. The decomposition of Ch in this period is less visible on the DTA curves for samples from QIII because it overlaps with an intense carbonate reaction.

The decomposition of carbonates is observed between 695 and 790°C in all QII and some QIII samples, indicating the presence of dolomite, which deteriorates at higher temperatures. The degradation of dolomite is accompanied by an expansion of the samples.

In some M samples, dilatometric analysis reveals sharp shrinkage peaks around 850°C (Table 1), with minimal DTA temperature changes. The effect is attributed to the highest I/M contents. Destruction of the illite structure finishes up to 850°C, and a simultaneous appearance of spinel and amorphous matter occurs [67]. Following this, the samples expanded up to 925°C due to the high illite content in the raw material and low melting behavior [59,68]. This second expansion may also result from the growth of gaseous dissociation products [69].

Further, a period of energetic and dimensional stability is observed, leading to the onset of sintering between 803 and 930°C, varying by sample. The near-plateau shape up to 930°C reflects the combined effects of kaolinite dehydroxylation and shrinkage, illite expansion, quartz contraction, amorphous matter formation (spreading), and mineral expansion [66]. Sintering begins earlier in raw clays with higher Na2O and K2O content due to their positive impact on the sintering process [59]. Dilatometric curves of QIV clays show typical stair-step shrinkage of kaolins [70], starting around 580°C, slowing at 640°C, continuing until 900°C, and then accelerating shrinkage [65]. The presence of illite slightly inhibited the contraction of kaolinite [27].

DTA curves for samples with higher kaolinite content revealed exothermic peaks above 911°C in all samples, corresponding to the crystallization of primary mullite, spinel, hematite, and/or amorphous silica appearance, with hematite presence leading to lower temperature peaks [32,59,62]. Samples with less kaolinite reach this peak earlier than those from QI and QIV. This is followed by shrinkage and further vitrification.

During cooling, the largest changes are found in the samples from QI, with the maximum in GC6, showing the highest quantity of quartz [7].

Chemical compositional variation of traditional ceramic productsIn summary, the obtained chemical composition variations of raw clays shown suitable for various applications in the production of ceramics are presented in Table 6. Similar shares of Al2O3 are noticed as needed in ceramic and roofing tiles, with the main differences in the content of Fe2O3. These two groups presented close maturity of sediments, as calculated using the ICV. Common bricks and blocks can be produced of much less mature raw clays, with a wide diversity of chemical compositions. From the available data in the literature concerning the proven usability of raw materials, also different sources than here obtained can be implemented. It must be highlighted that the compositions obtained may significantly vary considering the technique employed. In the case XRF is used, then the sample preparation method and time of milling may introduce significant changes. By simply comparing the presented chemical compositions, it is seen that some examples from the literature present wider, while others show narrower ranges of oxides, as follows:

- •

In the porcelain ceramic tile production, the literature shows compositions varying from 53.9 to 72.9% of SiO2, 17.3 to 29.0% of Al2O3, 0.3 to 3.5% of Fe2O3, and 0.4 to 1.8% TiO2[37,60,71,72] with ICVs in the 0.1–0.5 range,

- •

In the roofing tile production, the compositions of 43.2 to 66.8% SiO2, 14.4 to 31.6% Al2O3, 5.0 to 9.4% Fe2O3, and 0.1 to 6.0% CaO [73–79] with ICVs in the 0.4–1.4 range,

- •

Raw clays for common bricks and blocks showed the presence of 51.2 to 68.7% SiO2, 12.2 to 21.4% Al2O3, 5.1 to 7.8% Fe2O3, and 1.4 to 11.0% CaO [33,59,78,80–83] with ICVs in the 0.6–1.8 range, and

- •

Low-duty refractory materials made of raw clay may contain 40.4–66.0% SiO2, 25.7–38.7% Al2O3, 0.2–7.4% Fe2O3, and a considerably variable LOI between 2.8 and 13.8% [84–88]. The ICV ranges from 0.0 to 0.3.

Chemical composition variation of traditional ceramic products.

| Parameter (%) | Ceramic tiles | Roofing tiles and ceiling elements | Common bricks and blocks | Low-duty refractory materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOIa | 2.6–6.3 | 5.4–13.0 | 11.9–19.9 | 9.5–16.3 |

| SiO2 | 60.7–69.8 | 50.4–63.9 | 39.9–51.9 | 48.9–57.3 |

| Al2O3 | 15.6–24.2 | 14.1–24.7 | 11.4–14.6 | 24.6–28.2 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.0–5.4 | 4.9–8.8 | 4.4–7.4 | 2.5–3.4 |

| CaO | 0.2–1.9 | 0.5–8.2 | 3.4–15.5 | 0.4–0.9 |

| MgO | 1.2–2.0 | 2.3–6.2 | 3.9–7.4 | 0.6–1.2 |

| Na2O | 0.2–0.8 | 0.6–1.9 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.3–0.6 |

| K2O | 1.7–3.4 | 1.6–4.1 | 1.8–2.3 | 0.6–2.5 |

| TiO2 | 0.6–0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.8–1.0 |

| ICVb | 0.3–0.8 | 0.4–0.6 | 1.4–2.6 | ≤0.3 |

Concerning the maturity of sediments, which reflects the quantity of clay minerals in the examined samples compared to those from Serbia, it appears that the global raw materials used in ceramic tiles making are somewhat more mature, those for roofing tiles are made of the same or somewhat younger sediments, common bricks are produced of wealthier clays, while low-duty refractory materials present in the literature are of the same maturity.

ConclusionsThis study tested 50 raw clays of various types to distinguish possible ceramic products. The chemical and mineralogical compositions were followed, along with their behavior during the firing process. Using Principal Components Analysis, the clay samples were categorized into four groups, each suitable for producing different traditional ceramics. Another set of industrially used raw materials was tested to validate these results. A group with high clay mineral content, indicating geological maturity, is valuable for the ceramic tile industry. The second group includes raw clays with insufficient geological maturity and high Fe2O3 content, making them suitable for common bricks and roofing tiles. Geologically immature raw clays with high carbonate content are best suited for heavy clay products like bricks and hollow bricks due to their high LOI values and sand-silt fractions. Raw clays with the highest clay mineral content and with sufficient geological maturity are appropriate for refractory applications despite the unwanted iron content. Future research could focus on developing a more extensive and detailed database obtained in the same ways to further refine this approach and advance toward a general method for classifying clays.

Author contributionsMilica V. Vasić: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Osman Gencel: Writing – review & editing. Pedro Muñoz Velasco: Writing – review & editing.

FundingThis investigation is financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation (contract no.: 451-03-136/2025-03/200012).

Conflict of interestNone.