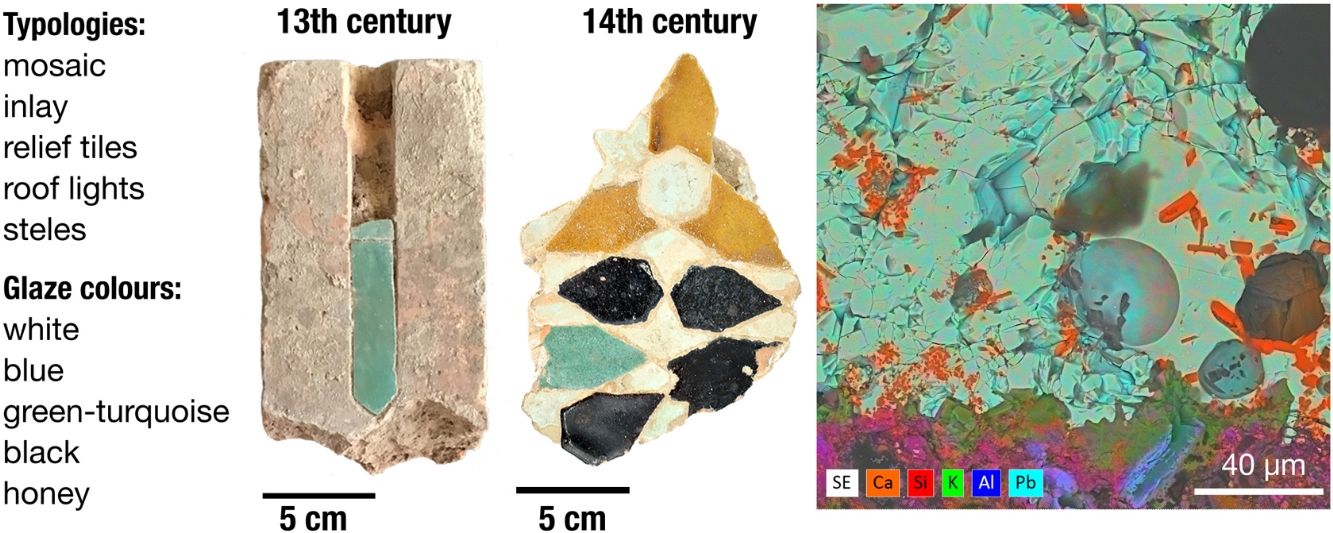

This work presents the first systematic archaeometric data of 13th–14th century AD Nasrid glazed architectural ceramics from the Alhambra and Generalife, focusing on colour-specific glazing technologies. Findings provide new insights into Nasrid glazing technology, ceramic typologies, and conservation implications, contributing to discussions on Islamic material culture and technical traditions in al-Andalus. Analysed typologies include mosaic, inlay, relief tiles, roof lights, and steles with glazes in white, blue, green-turquoise, black, and honey tones. Microstructural and chemical results reveal decorative chromophores and techniques to be a reference for future studies. Most glazes are inglaze on lead tin-opacified bases, fired in oxidising conditions at ∼950°C. Phosphorus was found in weathered glazes (associated with a burial environment) and unweathered white and blue glazes, suggesting deliberate addition of bones (fragments/ashes). Identified phases in most glazes were unmelted quartz and feldspars grains, and relatively abundant Cr-bearing wollastonite crystals precipitated during firing. Furthermore, one of the fragments with a black surface was determined not to be a glaze, but rather a polished section of a metamorphic rock.

Este trabajo presenta datos del primer análisis arqueométrico sistemático de cerámicas vidriadas arquitectónicas de los siglos XIII y XIV n.e. de la Alhambra y Generalife, centrándose en la tecnología de esmaltado de diversos colores. Los resultados ofrecen nuevas perspectivas sobre la tecnología del vidriado nazarí, las tipologías cerámicas y su estado de conservación. Estos hallazgos permiten abordar una discusión más amplia de la cultura material islámica y de las tradiciones técnicas de al-Andalus. Las tipologías cerámicas estudiadas incluyen alicatados, incrustados, sebkas, lucernarios y bordillos funerarios coloreados en blanco, azul, verde-turquesa, negro y melado. Los resultados microestructurales y químicos revelan que los cromóforos y técnicas decorativas en determinados tipos cerámicos pueden servir como marcadores en estudios futuros. Los esmaltes son de plomo opacificados con estaño, y cocidos en atmósfera oxidante a unos 950°C. Se detectó fósforo en muestras alteradas (relacionado con condiciones de enterramiento), y en esmaltes blancos y azules no alterados, lo que sugiere la adición deliberada de huesos o cenizas óseas al vidriado. Asimismo, se identificaron en la mayoría de los esmaltes granos de cuarzo y feldespatos no fundidos, y abundantes precipitados de wollastonita con trazas de cromo. Además, se determinó que uno de los fragmentos con decoración negra no era un vidriado, sino una sección pulida de una roca metamórfica.

Archaeometric studies of glazed ceramics have achieved significant maturity, employing a range of analytical techniques to yield insights into ancient manufacturing processes, chromophores, and degradation mechanisms [1–11]. Quantitative assessments of glaze constituents, coupled with analyses of refractory and crystallisation phases, and structure and morphology examination of the glaze–ceramic interface, offer significant information [2,7,12]. Analyses reveal details of manufacturing processes such as firing temperature, atmospheric firing conditions, firing stage sequences, and colour techniques [7,9,10]. Data provide historical insights, including trade or local sourcing of raw materials, adaptation of foreign techniques, aesthetic evolution [13], and likewise strategies for conservation and restoration.

Architectural ceramics, compared with tableware ceramics [1–4,8,9,14,15], are not as extensively analysed, although studies have been conducted in Portugal [5,16], Spain [11,17,18], Mesopotamia and Middle-East regions [19,20]. Noteworthy are the Nasrid architectural ceramics, specifically from the Alhambra and Generalife [21,22]. The Nasrid period refers to the era between AD 1232 and 1492 during which the Nasrid dynasty ruled the Granada Emirate, the last Muslim state in the Iberian Peninsula. The Alhambra architectural ceramics have been studied by historians and archaeologists [21,23]. However, their analysis remains challenging because the monument dimension, unrecorded relocations of ceramic pieces, undocumented and Christian interventions, and chronologies based on artistic and stylistic features. Chronologies need reassessment considering archaeometric and interdisciplinary investigations. Today archaeometric studies of Nasrid glazed architectural ceramics are still emerging and remains non-systematic [17,21,24–29]. However, most recent results reveal their lead tin-opacified composition [7,28].

This study is part of an interdisciplinary research and presents a morphological and chemical analysis of coloured glazed architectural ceramics from the Alhambra and Generalife dated on 13th–14th century AD according to decoration [30]. The aim is to improve knowledge on their chronology and technology of fabrication.

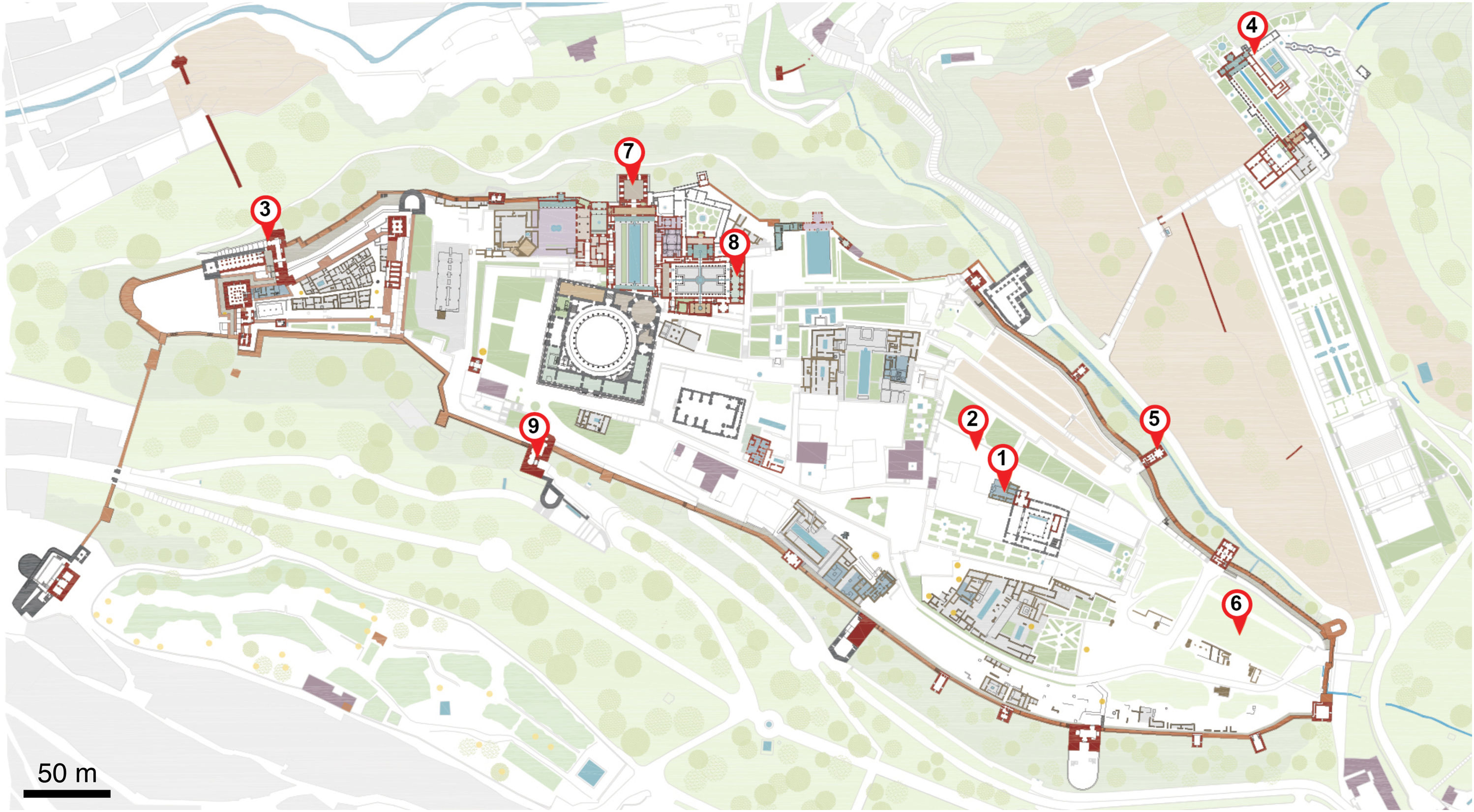

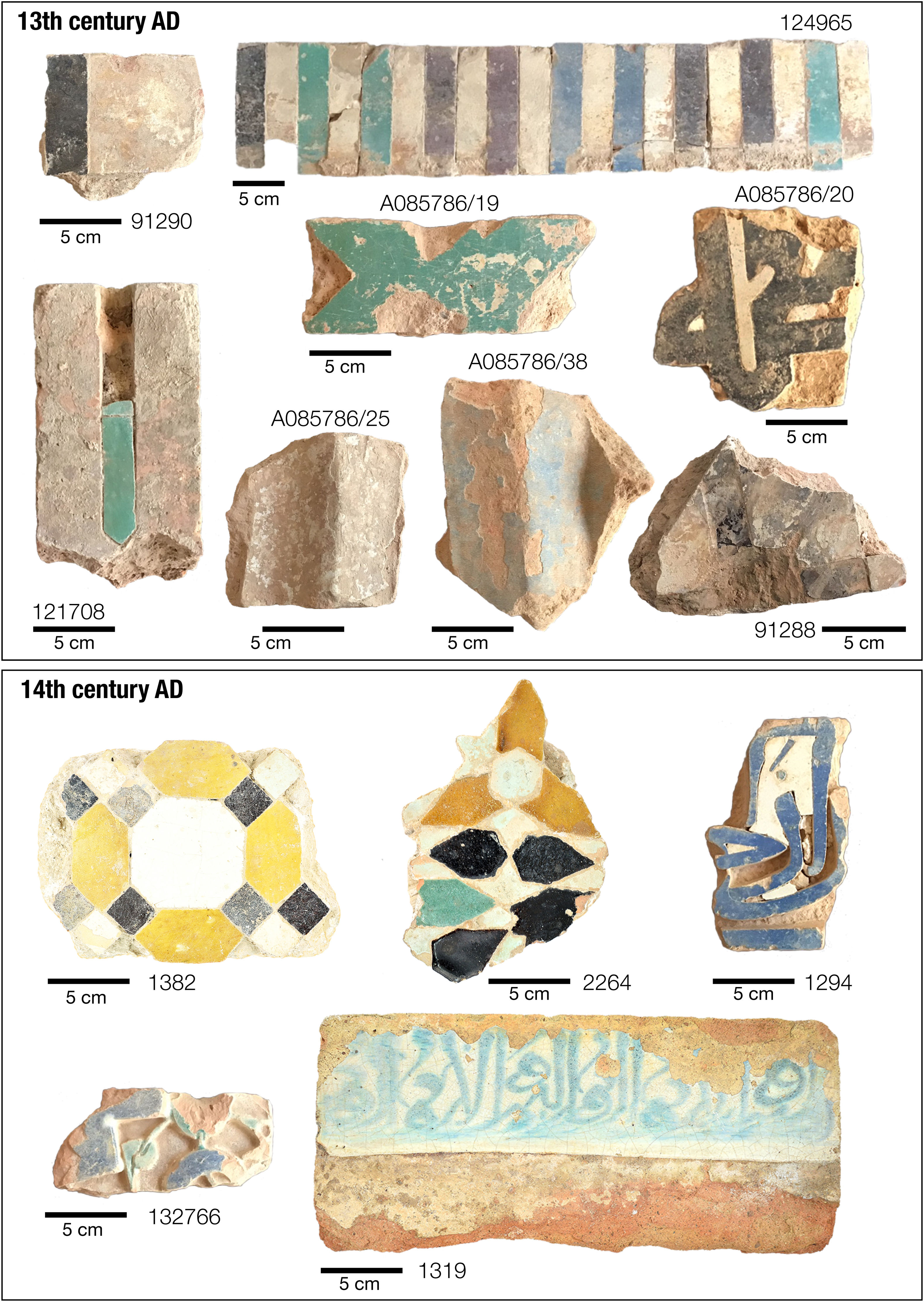

Materials and methodsMaterialsThirteen architectural ceramic pieces from key locations within the Alhambra and Generalife (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1, Table S1 and Appendix 1) featuring geometric patterns, vegetal motifs and Arabic calligraphy, were studied. Pieces are housed in the Museum's private storage of the Alhambra. Information for each piece is recorded in the Integrated Museum Documentation and Management System (DOMUS [22]) of the monument (Table 1 and Table S1). Pieces exhibit white, blue, green-turquoise, black and honey colour, and correspond to Alicatado (mosaic tiling), Incrustado (inlay tiles), Lucernario (rooflight fragments), Sebka (relief tiles), and Bordillo (funerary steles), illustrating diverse functions (Table S1).

Map of the Alhambra and Generalife Monument (Granada, Spain) with the original location of the studied glazed ceramics; site 1: Bath of the Monastery of San Francisco (archaeological site); site 2: Garden of the Monastery of San Francisco (archaeological site), site 3: Gate of the Arms; site 4: Generalife; site 5: Tower of the Captive; site 6: City of the Alhambra (Medina); site 7: Hall of the Kings at the Lion Palace, site 8: Gate of Justice.

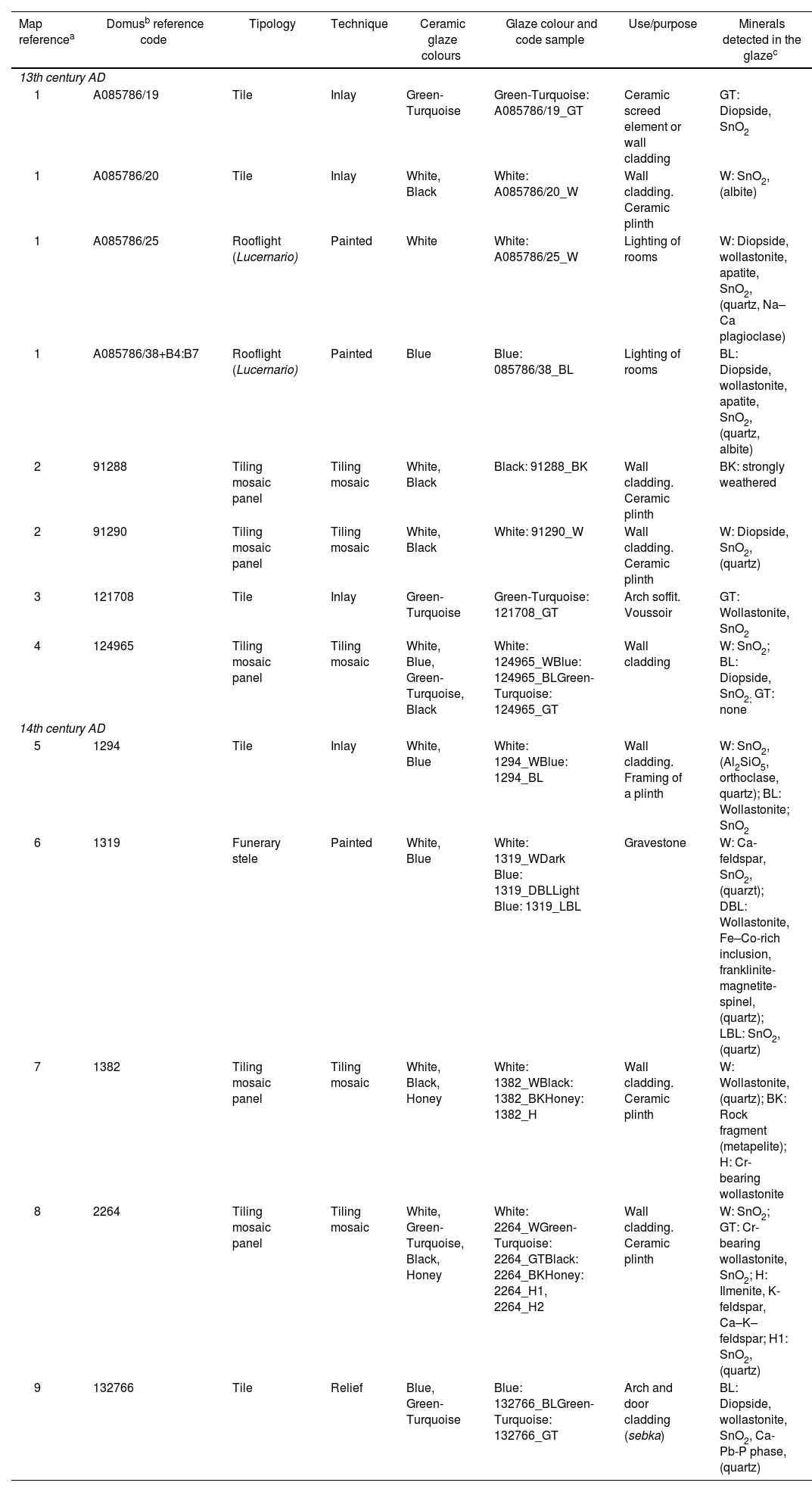

Characteristics of studied glazed architectural ceramics from the Alhambra and Generalife.

| Map referencea | Domusb reference code | Tipology | Technique | Ceramic glaze colours | Glaze colour and code sample | Use/purpose | Minerals detected in the glazec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century AD | |||||||

| 1 | A085786/19 | Tile | Inlay | Green-Turquoise | Green-Turquoise: A085786/19_GT | Ceramic screed element or wall cladding | GT: Diopside, SnO2 |

| 1 | A085786/20 | Tile | Inlay | White, Black | White: A085786/20_W | Wall cladding. Ceramic plinth | W: SnO2, (albite) |

| 1 | A085786/25 | Rooflight (Lucernario) | Painted | White | White: A085786/25_W | Lighting of rooms | W: Diopside, wollastonite, apatite, SnO2, (quartz, Na–Ca plagioclase) |

| 1 | A085786/38+B4:B7 | Rooflight (Lucernario) | Painted | Blue | Blue: 085786/38_BL | Lighting of rooms | BL: Diopside, wollastonite, apatite, SnO2, (quartz, albite) |

| 2 | 91288 | Tiling mosaic panel | Tiling mosaic | White, Black | Black: 91288_BK | Wall cladding. Ceramic plinth | BK: strongly weathered |

| 2 | 91290 | Tiling mosaic panel | Tiling mosaic | White, Black | White: 91290_W | Wall cladding. Ceramic plinth | W: Diopside, SnO2, (quartz) |

| 3 | 121708 | Tile | Inlay | Green-Turquoise | Green-Turquoise: 121708_GT | Arch soffit. Voussoir | GT: Wollastonite, SnO2 |

| 4 | 124965 | Tiling mosaic panel | Tiling mosaic | White, Blue, Green-Turquoise, Black | White: 124965_WBlue: 124965_BLGreen-Turquoise: 124965_GT | Wall cladding | W: SnO2; BL: Diopside, SnO2; GT: none |

| 14th century AD | |||||||

| 5 | 1294 | Tile | Inlay | White, Blue | White: 1294_WBlue: 1294_BL | Wall cladding. Framing of a plinth | W: SnO2, (Al2SiO5, orthoclase, quartz); BL: Wollastonite; SnO2 |

| 6 | 1319 | Funerary stele | Painted | White, Blue | White: 1319_WDark Blue: 1319_DBLLight Blue: 1319_LBL | Gravestone | W: Ca-feldspar, SnO2, (quarzt); DBL: Wollastonite, Fe–Co-rich inclusion, franklinite-magnetite-spinel, (quartz); LBL: SnO2, (quartz) |

| 7 | 1382 | Tiling mosaic panel | Tiling mosaic | White, Black, Honey | White: 1382_WBlack: 1382_BKHoney: 1382_H | Wall cladding. Ceramic plinth | W: Wollastonite, (quartz); BK: Rock fragment (metapelite); H: Cr-bearing wollastonite |

| 8 | 2264 | Tiling mosaic panel | Tiling mosaic | White, Green-Turquoise, Black, Honey | White: 2264_WGreen-Turquoise: 2264_GTBlack: 2264_BKHoney: 2264_H1, 2264_H2 | Wall cladding. Ceramic plinth | W: SnO2; GT: Cr-bearing wollastonite, SnO2; H: Ilmenite, K-feldspar, Ca–K–feldspar; H1: SnO2, (quartz) |

| 9 | 132766 | Tile | Relief | Blue, Green-Turquoise | Blue: 132766_BLGreen-Turquoise: 132766_GT | Arch and door cladding (sebka) | BL: Diopside, wollastonite, SnO2, Ca-Pb-P phase, (quartz) |

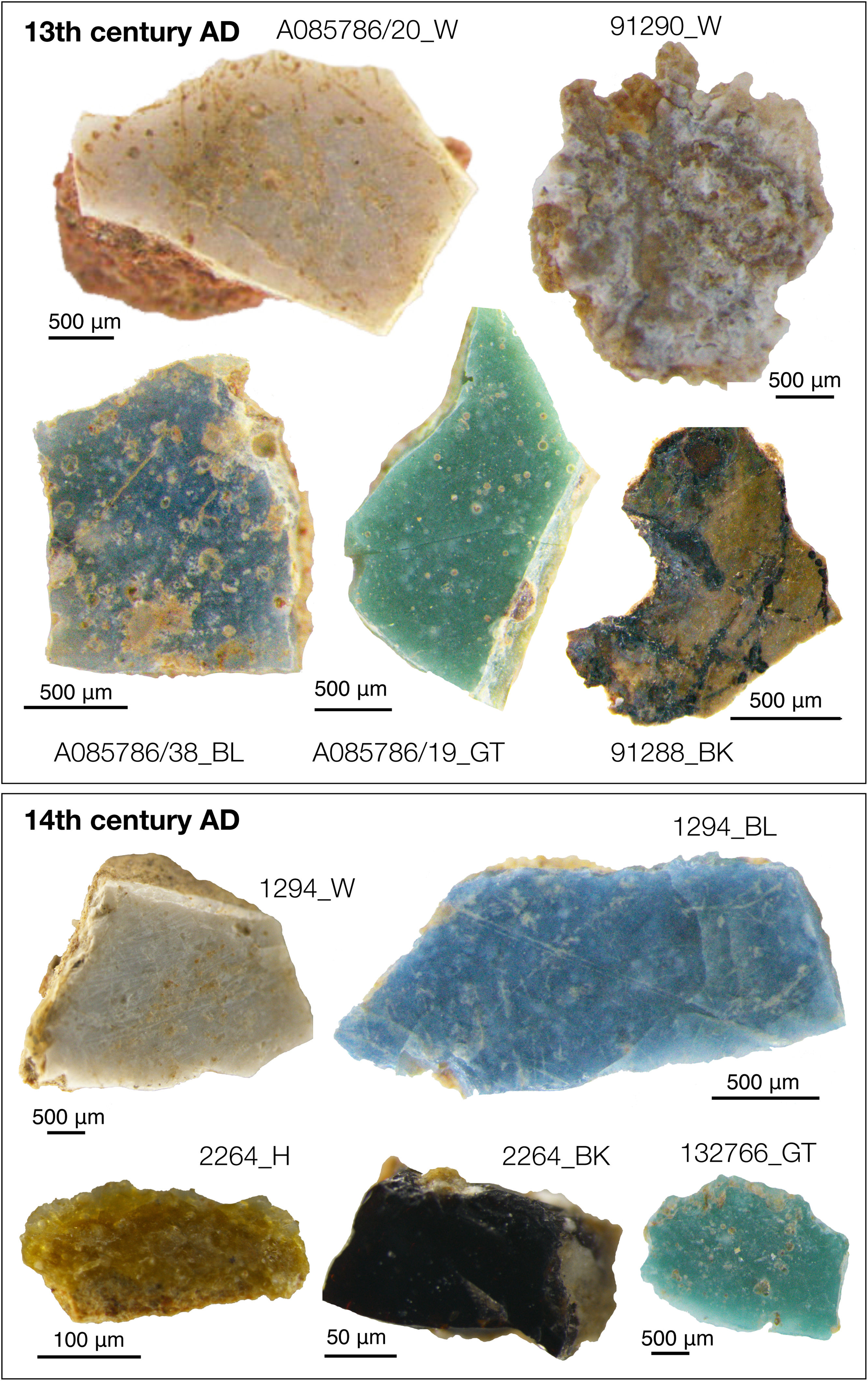

A stereomicroscope (Leica VDM 2000) documented macroscopic features of samples (Fig. 3). Samples were embedded within epoxy mounts and polished to achieve cross-sections. Mineralogical and microstructural analyses were performed employing a Carl Zeiss Jenapol-U polarised optical microscope (OM), coupled to a Nikon D7000 digital camera. Observations encompassed transmitted and reflected light under plane and cross-polarised conditions.

High-resolution backscattered electron (BSE) and secondary electron (SE) imaging were acquired from carbon-coated thin sections under a high vacuum using two scanning electron microscopes (SEM). A field emission environmental SEM (FE-ESEM) QuemScan 650F equipped with a CBS detector for BSE. By using a Dual EDS XFlash of Bruker with a XFlash 6/30 detector, EDS microanalyses and elemental maps were obtained in selected point and areas respectively. Also, a Zeiss SUPRA40VP FE-SEM was used, equipped with X-Max 50mm2 EDS detector (AZTEC v.3), enabling point and surface analyses, and compositional mapping. Quantitative analyses (normalised) were obtained using AZTEC certified pure element and compound standards (Table S2).

Chemical characterisation began with low-magnification BSE imaging, including the glaze and ceramic body, and to identify pristine and weathered glaze regions. Inferred original glaze composition was estimated through surface analyses of three to five regions (from ca. 150×100 to 70×50μm2), using 15kV accelerating voltage and 8.5mm working distance. Average composition of areas was reported as oxides (weight %). Measurement reliability was ensured by evaluating the distribution homogeneity of quench materials. The surface measured by EDS mapping is representative for Sn based on the small size (<1μm) and homogenous distribution of SnO2, but it might underestimate the amount of Ca, Mg, Si and P, based on larger size and non-homogeneous distribution of pyroxene, wollastonite and apatites.

EDS single-point analyses were conducted in crystal precipitates and unmelted crystals. Complex phases were validated through stoichiometric calculations). Subsequent BSE imaging of glaze–ceramic interfaces was done to investigate chemical reactions and diffusion processes. X-ray maps (1024×768 pixels, 10ms dwell time, 2.5h acquisition, 20eV/channel resolution) were acquired from areas of interest.

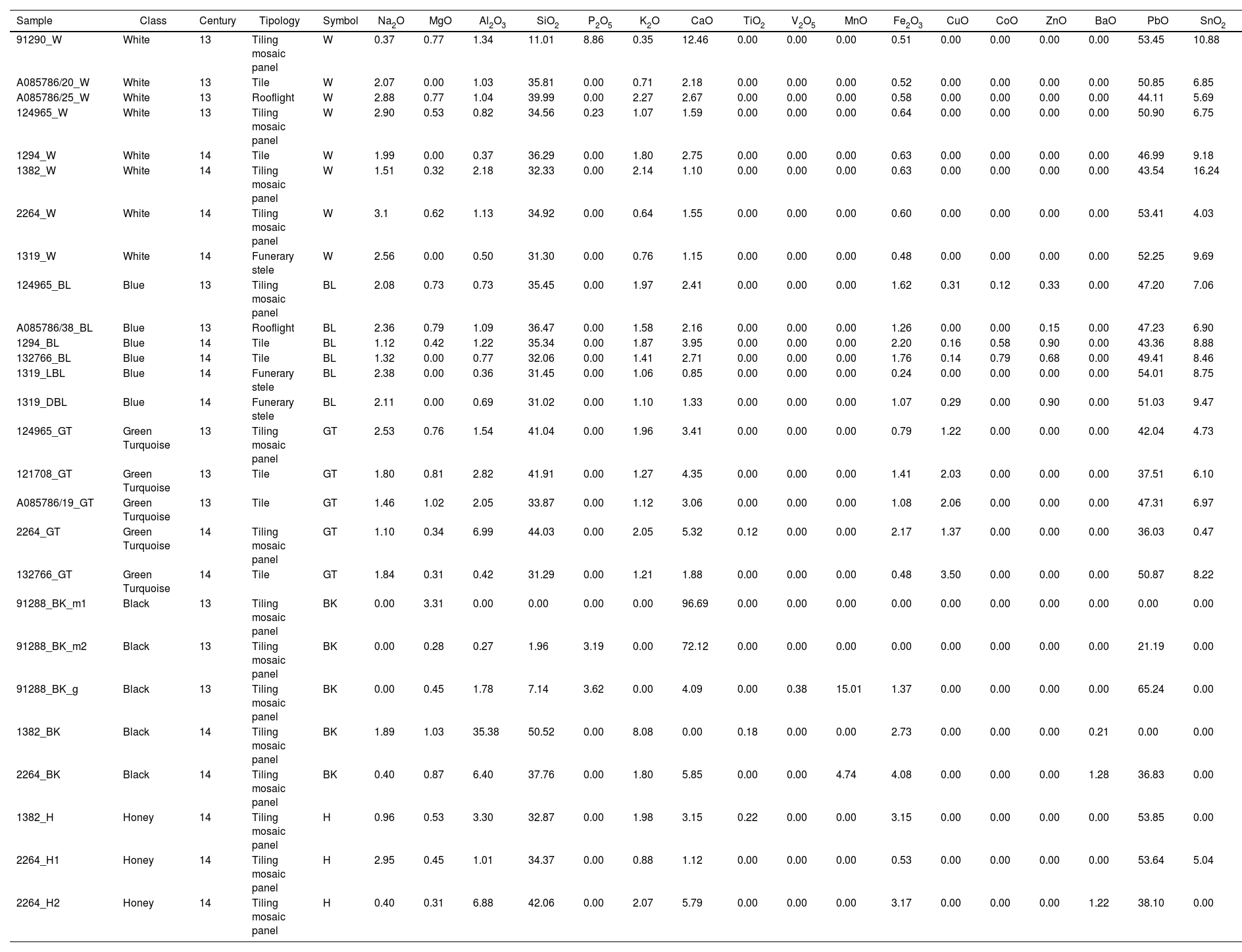

Results and discussionChemical data are presented according to glaze colours (Table 2) to discern recipes according to ceramic typology or chronology, and to determine ceramic reference groups. Note that the 13th century AD ceramics from the Monastery of San Francisco (Table S1) are considered original Nasrid pieces and they have never been intervened. Hence, their characteristics are a benchmark of this period. Comparison of Nasrid glazes’ compositions with contemporaneous architectural ceramics is limited due to the scarcity of relevant bibliographic sources (see Table S3 for compositional data on comparable coeval coloured glazes).

Average quantitative EDS analyses (wt.%) of the investigated glazes.

| Sample | Class | Century | Tipology | Symbol | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | V2O5 | MnO | Fe2O3 | CuO | CoO | ZnO | BaO | PbO | SnO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91290_W | White | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | W | 0.37 | 0.77 | 1.34 | 11.01 | 8.86 | 0.35 | 12.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 53.45 | 10.88 |

| A085786/20_W | White | 13 | Tile | W | 2.07 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 35.81 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 2.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.85 | 6.85 |

| A085786/25_W | White | 13 | Rooflight | W | 2.88 | 0.77 | 1.04 | 39.99 | 0.00 | 2.27 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 44.11 | 5.69 |

| 124965_W | White | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | W | 2.90 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 34.56 | 0.23 | 1.07 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.90 | 6.75 |

| 1294_W | White | 14 | Tile | W | 1.99 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 36.29 | 0.00 | 1.80 | 2.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 46.99 | 9.18 |

| 1382_W | White | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | W | 1.51 | 0.32 | 2.18 | 32.33 | 0.00 | 2.14 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 43.54 | 16.24 |

| 2264_W | White | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | W | 3.1 | 0.62 | 1.13 | 34.92 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 1.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 53.41 | 4.03 |

| 1319_W | White | 14 | Funerary stele | W | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 31.30 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 52.25 | 9.69 |

| 124965_BL | Blue | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | BL | 2.08 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 35.45 | 0.00 | 1.97 | 2.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.62 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 47.20 | 7.06 |

| A085786/38_BL | Blue | 13 | Rooflight | BL | 2.36 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 36.47 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 2.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 47.23 | 6.90 |

| 1294_BL | Blue | 14 | Tile | BL | 1.12 | 0.42 | 1.22 | 35.34 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 3.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.20 | 0.16 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 43.36 | 8.88 |

| 132766_BL | Blue | 14 | Tile | BL | 1.32 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 32.06 | 0.00 | 1.41 | 2.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.76 | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 49.41 | 8.46 |

| 1319_LBL | Blue | 14 | Funerary stele | BL | 2.38 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 31.45 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 54.01 | 8.75 |

| 1319_DBL | Blue | 14 | Funerary stele | BL | 2.11 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 31.02 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 51.03 | 9.47 |

| 124965_GT | Green Turquoise | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | GT | 2.53 | 0.76 | 1.54 | 41.04 | 0.00 | 1.96 | 3.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 1.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 42.04 | 4.73 |

| 121708_GT | Green Turquoise | 13 | Tile | GT | 1.80 | 0.81 | 2.82 | 41.91 | 0.00 | 1.27 | 4.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.41 | 2.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 37.51 | 6.10 |

| A085786/19_GT | Green Turquoise | 13 | Tile | GT | 1.46 | 1.02 | 2.05 | 33.87 | 0.00 | 1.12 | 3.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 2.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 47.31 | 6.97 |

| 2264_GT | Green Turquoise | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | GT | 1.10 | 0.34 | 6.99 | 44.03 | 0.00 | 2.05 | 5.32 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.17 | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 36.03 | 0.47 |

| 132766_GT | Green Turquoise | 14 | Tile | GT | 1.84 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 31.29 | 0.00 | 1.21 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.87 | 8.22 |

| 91288_BK_m1 | Black | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | BK | 0.00 | 3.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 96.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 91288_BK_m2 | Black | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | BK | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 1.96 | 3.19 | 0.00 | 72.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 21.19 | 0.00 |

| 91288_BK_g | Black | 13 | Tiling mosaic panel | BK | 0.00 | 0.45 | 1.78 | 7.14 | 3.62 | 0.00 | 4.09 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 15.01 | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 65.24 | 0.00 |

| 1382_BK | Black | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | BK | 1.89 | 1.03 | 35.38 | 50.52 | 0.00 | 8.08 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2264_BK | Black | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | BK | 0.40 | 0.87 | 6.40 | 37.76 | 0.00 | 1.80 | 5.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.74 | 4.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.28 | 36.83 | 0.00 |

| 1382_H | Honey | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | H | 0.96 | 0.53 | 3.30 | 32.87 | 0.00 | 1.98 | 3.15 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 53.85 | 0.00 |

| 2264_H1 | Honey | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | H | 2.95 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 34.37 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 53.64 | 5.04 |

| 2264_H2 | Honey | 14 | Tiling mosaic panel | H | 0.40 | 0.31 | 6.88 | 42.06 | 0.00 | 2.07 | 5.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 38.10 | 0.00 |

White glazes exhibit significant compositional variability (Table 2). However, except for the weathered 91290_W glaze, all are classified as lead tin-opacified glazes [2]. Differences in composition are associated with ceramic typology rather than chronology, excluding some 14th century AD pieces, as discussed below.

Tiling mosaic panelsThe 13th century AD 124965_W glaze (520μm thick) has the lowest Al2O3 content (0.82wt.%) compared to the 14th century AD glazes 1382_W (220μm thick) and 2264_W (330μm thick), which contain 2.18 and 1.13wt.%, respectively. Additionally, glaze 124965_W holds phosphorous (P, expressed as P2O5 at 0.23wt.%, Table 2), related to weathering (discussed below) as confirmed by surface pitting and microcracking.

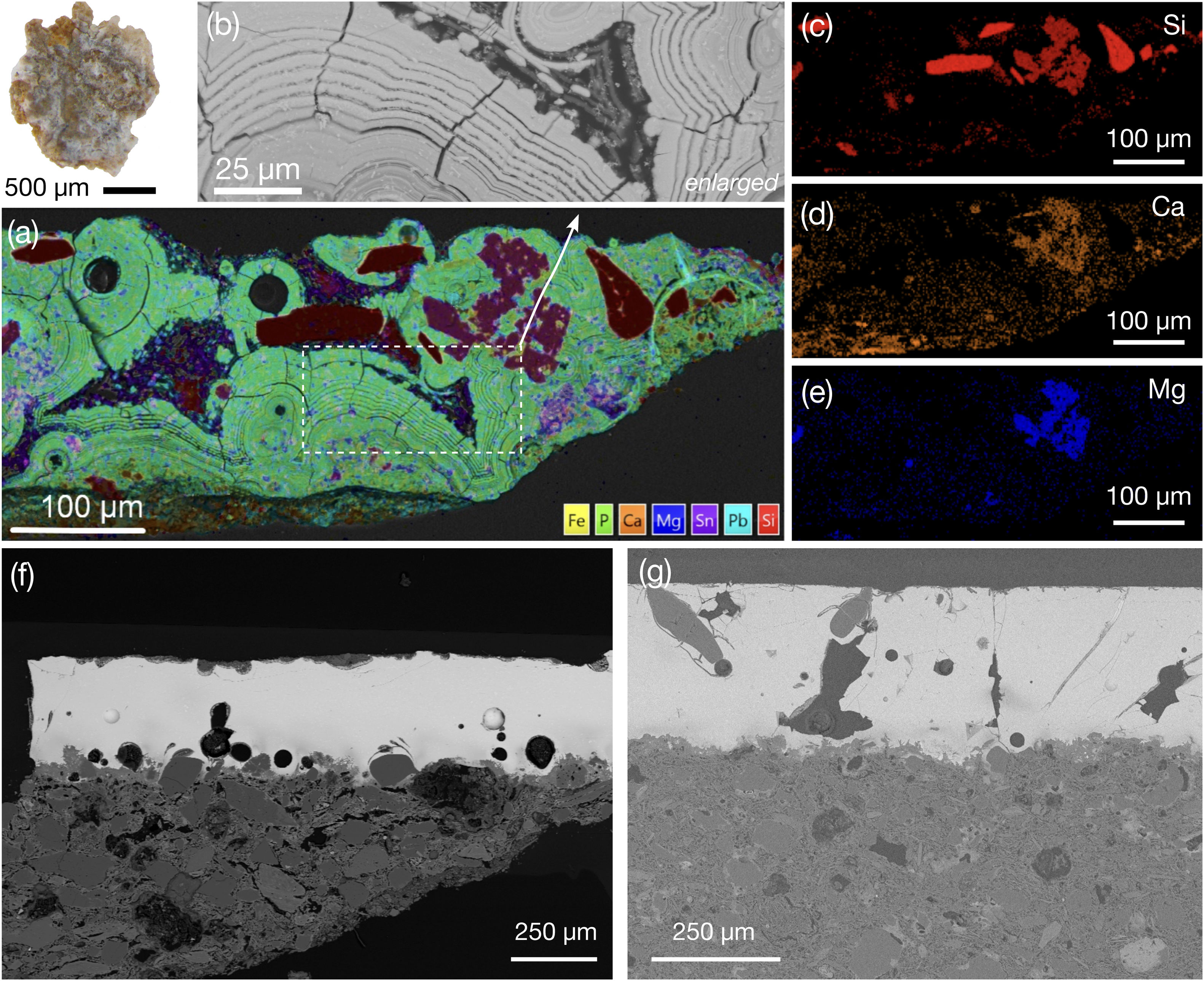

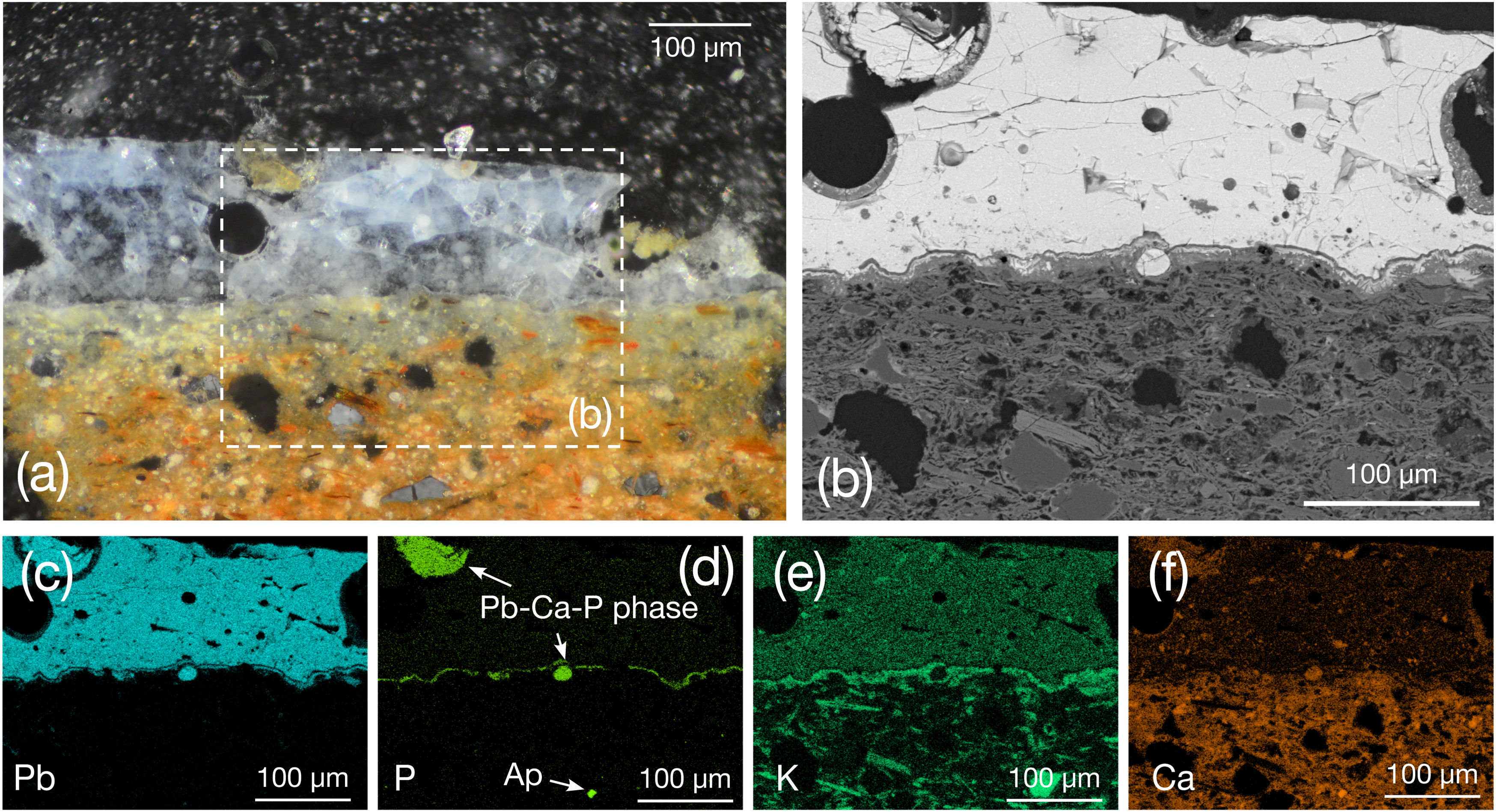

Composition of the 13th century AD glaze 91290_W (480μm thick) must be interpreted with caution because this glaze exhibits severe degradation characterised by concentric pattern of alternating Sn- and Pb-rich rings (Fig. 4a and b), known as Liesegang rings [7], also found in other degraded architectural glazed ceramics at the Alhambra [28]. Bubbles, elongated rounded quartz – SiO2 – bodies (Fig. 4c), and diopside – CaMgSi2O6 – precipitates (Fig. 4c–e) are observed. Chemical weathering is related with burial-induced transformation processes, wherein glazes are exposed to stagnant water. This environment promotes two concurrent weathering mechanisms: vitreous matrix dissolution and leaching of alkali elements. Low concentrations of Na2O (0.37wt.%) and K2O (0.35wt.%) suggest dealkalisation. Furthermore, weathering is marked by insoluble compounds precipitation, e.g., Ca/Pb-rich phosphates [31]. Notably, glaze 91290_W contains the highest P (8.86wt.%) and Ca (CaO at 12.46wt.%) concentrations of all studied white glazes (Table 2). Although some P could proceed from the soil, the high P concentration suggests that it could have been deliberately added to the glaze. Indeed, SEM-BSE images show tubular structures attributable to bone fragments (Fig. S1). Bone (fragments/ashes) have been used to opacify glass artifacts of diverse chronology, glazed tesserae and tableware ceramics and porcelain; however, its use is limited in glazed tiles [6,32,33]. Noteworthy, bone fragments were also detected in the ceramic body of Nasrid architectural ceramics in the Alhambra [28].

Chemical analysis of glaze 91290_W (Table 2) shows the average composition of three areas which include bubbles and rings (Fig. 4a and 4b). Some layers are low in Si, which accounts for the low SiO2 content (Table 2). SEM analyses reveal that Si concentrates as quartz-rich bodies along Liesegang rings (Fig. 4a and c), whereas original unmelted quartz grains and dendritic diopside remained unaltered (Fig. 4d and e; Table S4: sample 91290_W – spectrum 12 [34]). Note that diopside precipitation constrains the firing temperature to be above 900°C [8].

Glazes 1382_W and 2264_W (14th century AD) exhibit great compositional variability, particularly in SnO2 (16.24wt.% and 4.03wt.%), PbO (43.5wt.% and 53.4wt.%), Na2O (1.51wt.% and 3.10wt.%), and K2O (2.14wt.% and 0.64wt.%) (Table 2). This is surprising considering that both ceramics share typology and chronology, though proceed from different Nasrid palaces. Ceramic 1382 is from the Comares Palace, built by Yusuf I (1333–1354), whereas ceramic 2264 comes from the Lions Palace, constructed under Muhammad V (1362–1391). Muhammad V introduced design and technology innovations in the Alhambra ornamentation. He had a close alliance with the Christian king Pedro I of Castile. The emir sent craftsmen to the Palace of Pedro I, the Alcázar of Seville, built between 1356 and 1366. Consequently, the distinct composition of glazed ceramics from the Lions Palace is interpreted as intentional, rather than due to inadequate workmanship by Nasrid artisans.

Inlaid tiles, funerary stele and rooflight ceramicWhite glazes of tiles A085786/20_W (280μm thick) and 1294_W (320μm thick) (Fig. 4f and g) exhibit similar SiO2 contents, though differ in Al2O3, Na2O, K2O, and SnO2 (Table 2). While both glazes are lead tin-opacified glazes [2], A085786/20_W is lower in alkalis (2.78wt.%) and SnO2 (6.85wt.%) compared to 1294_W. Albite (NaAlSi3O8) subhedral aggregate crystals, some associated to acicular K–Pb feldspars, were found in A085786/20_W near the interface (Table S4, spectrum 136). Neither glaze contains large MgO amounts, as also found in the 14th century AD funerary stele glaze 1319_W (Fig. 2). This one exhibits the lowest SiO2 (31.30wt.%), K2O (0.76wt.%), Al2O3 (0.50wt.%), and CaO (1.15wt.%) contents among all analysed unweathered white glazes, though holds the highest PbO (52.25wt.%) and SnO2 (9.69wt.%) concentrations (Table 2). This composition may serve as a ceramic typology fingerprint.

Glaze A085786/25_W (rooflight) composition precludes a straightforward classification according to Ref. [2] thereby distinguishing it from the other white glazes. This glaze (thickness ∼180μm) Exhibits 44.11wt.% of PbO, the highest alkali content among the white glazes (2.88wt.% Na2O and 2.27wt.% K2O), the highest SiO2 content (39.99wt.%), and elevated CaO levels (2.67wt.%). Conversely, its low PbO content suggest a specific recipe associated with this ceramic typology (Table 2).

Microstructure and morphological featuresSEM observations reveal unmelted rounded quartz grains, and glaze–ceramic interfaces of varied thickness (∼40 to 100μm) in all white glazes (Fig. 4f and g). Although acicular K–Pb feldspar crystals are minute and discontinuous within some interfaces, their presence is widespread and, occasionally, accompanied by orthoclase (KAlSi3O8; glaze 1294_W, spectrum 140, Table S4). K and Al diffusion at interfaces suggest a single-firing process [2,7,35,36]. SEM microanalysis also revealed diopside in A085786/25_W glaze (spectra 48 and 49), and refractory unmelted aluminosilicate phases (Al2SiO5) in 1294_W (spectrum 186), a phase present in soils surrounding the city of Granada and sourced from the metamorphic rocks of Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Opacity in white glazes was achieved by varied cassiterite (SnO2) amounts (Table 2), as in the other coloured studied glazes, also depending on ceramic typology. Likewise, crystal size and distribution within the glaze matrix differ (Fig. S2). Nanometric cassiterite crystals (500–800nm), as found here, precipitate from the glaze ca. 900°C; moreover, homogeneous distribution suggests the fritting method to elaborate the tin-glaze [37]. Islamic glazes – on pottery – from the Iberian Peninsula were rich in PbO and SiO2, with contents varying according to coloured glazes. Quartz and feldspar inclusions, as here found in some white and coloured glazes, were likely used to enhance opacity, thus reducing costs derived from expensive tin oxide [37]. However, Ref. [38] states that the combined use of cassiterite and quartz for opacification, when one or the other would be enough, indicates that quartz was added to improve glaze viscosity. Considering the cassiterite amounts detected in all the studied glazes, enough to impart opacity, quartz/feldspars addition was not necessary, and may be related to glaze formulations used in these architectural ceramics [28].

White glazes recipes here analysed differ from those of the Mudejar Alcázar of Seville [17,39], containing less PbO and more SiO2, although both comprise quartz and diopside. Also diverge from other al-Andalus and Mudejar white lead glazes, e.g., ceramic tableware of Paterna in Valencia, Spain [40], and those from the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra (Portugal), which exhibit higher SnO2 and lower PbO contents [5,41]. Al-Andalus glazes followed the single-firing technique typical of late Islamic glaze technology [40], as found here.

Blue glazeCompositions differ according to ceramic typology (Table 2), all blue glazes being lead tin-opacified glazes [2]. PbO content ranges from 47.20 to 54.01wt.% with increased Pb levels correlating to higher SnO2 content. Alkalis are slightly higher in the 13th century AD glazes (3.94–4.05wt.%) than the 14th century AD glazes (2.73–3.34wt.%).

13th century AD blue glazesGlazes 124965_BL (260μm thick) and A085786/38_BL (180μm thick) exhibit crazing, crawling and pitting surface weathering [42,43]. P associated with Ca and/or Pb and vanadium (V), is present in fissures and the glaze surface. Vanadium, indicative of burial conditions, was also found in weathered glazes of Nasrid architectural ceramics in the Alhambra [28,31]. P was not detected in the glaze matrices; however, apatite precipitates in sample A085786/38_BL suggests that P was part of the original glaze (Table 2). SEM reveals subhedral to dendritic diopside associated with wollastonite and albite which indicates firing temperatures between 900 and 1000°C [7,8] and rapid crystallisation. Conversely, albite displays subhedral forms and dissolution patterns. Analogous albite crystals are abundant in the ceramic body, suggesting their incorporation into the glaze during the firing process. Notably, glaze A085786/38_BL is rich in diopside and wollastonite, and subhedral and tubular apatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH,F,Cl)) crystals (Fig. S3). This observation agrees with other reports where apatite and Ca-rich silicates are often spatially related in Ca-saturated glazes [6]. Additionally, it suggests that apatite, likely as bone fragments/ashes, was intentionally added to the glaze either as opacifier or to improve glaze emulsification.

OM and EDS analyses reveal differences in the firing process of 124965_BL and A085786/38_BL compared to other coloured glazes, probably linked to the apatite addition. Unlike other glazes, the acicular K–Pb feldspar-rich interface appears as a continuous thin layer (<10μm) of K-enriched glaze, along with a Si enrichment and Pb depletion. These features suggest a single-step firing process, though with a prominent physical interaction between the glaze and certain components of the ceramic body, notably albite and apatite crystals. These were likely detached from the ceramic body [35] and incorporated into the glaze due to their lower density relative to the lead glass, a process potentially enhanced by intense degassing of the ceramic body, also causing bubbles (∼80μm) and upward migration of immiscible Pb–Ca–P phase drops.

SEM investigation revealed that blue colour in glaze 124965_BL is due to Zn, Cu, Cr, Co, and Fe (Table 2), homogeneously dissolved in the glaze, rather than present as discrete precipitates [44]. In glaze A085786/38_BL, besides Cu and Zn dispersed in the glaze, Fe–Zn–Al precipitate (likely a franklinite-magnetite spinel, Table S4, spectrum 540) and Fe–Co-rich inclusions (Table S4, spectrum 532) were identified. Notably, Ni was not detected in these 13th century AD glazes. Noteworthy, in medieval glazes (tableware) from Valencia (Spain) there is an accepted evolution for Co-rich blue glazes based on chemical composition. Accordingly, the Co-Zn association is typical from the 12th and 13th century AD, while Ni is found in blue glazes from the 14th-15th century AD [45]. This supports the findings of this work and will validate the adscription of the blue glazes to the 13th century AD [30].

14th century AD blue glazesTwo blue tones from the funerary stele were analysed: 1319_LBL (light blue, 300μm thick) and 1319_DBL (dark blue, 480μm thick). Glazes contain abundant unmelted rounded quartz grains and have the lowest Ca content (CaO at 0.85–1.33wt.%) among all blue glazes. They primary differ in detected blue chromophores. 1319_LBL contains lower amounts of Fe and Cu, while Co and Zn are not found in the matrix. Note that Co detection limit in EDS is 0.1wt.%, and that lower Co amount can impart blue colour in enamels [6,28,41]. In glaze 1319_DBL, Fe, Co, Zn, and Cu are dissolved in the matrix. Additionally, Fe–Co–Zn-rich crystals are also recognised (Table S4). Both glazes exhibit surface pitting, with Ca-phosphates coating deposits. In 1319_LBL, surface is enriched in Co, Fe, and notably Cr, suggesting an overglaze decoration, while traces of Cu are dispersed throughout the glaze [6,17,44]. As discussed later, Cu is the key chromophore in green-turquoise glazes, aligning with the tendency of this light blue glaze to exhibit a turquoise hue.

Glaze 1294_BL (250μm thick) is comparable to glaze 124965_BL, as both exhibit crazing, and differ from A085786/38_BL, less affected by cracking. Surface of 1294_BL is unaltered. The glaze–ceramic interface is well-defined though enriched in acicular K–Pb feldspars, suggesting a single firing [8]. Skeletal wollastonite (spectrum 137, Table S4) aggregates (>200μm) are present in the glaze. Blue colour is due to Co, Cu, Fe, and Zn dissolved in the matrix (Table 2). No Fe–Co–Zn-rich inclusions are observed, though scarce diopside crystals are detected.

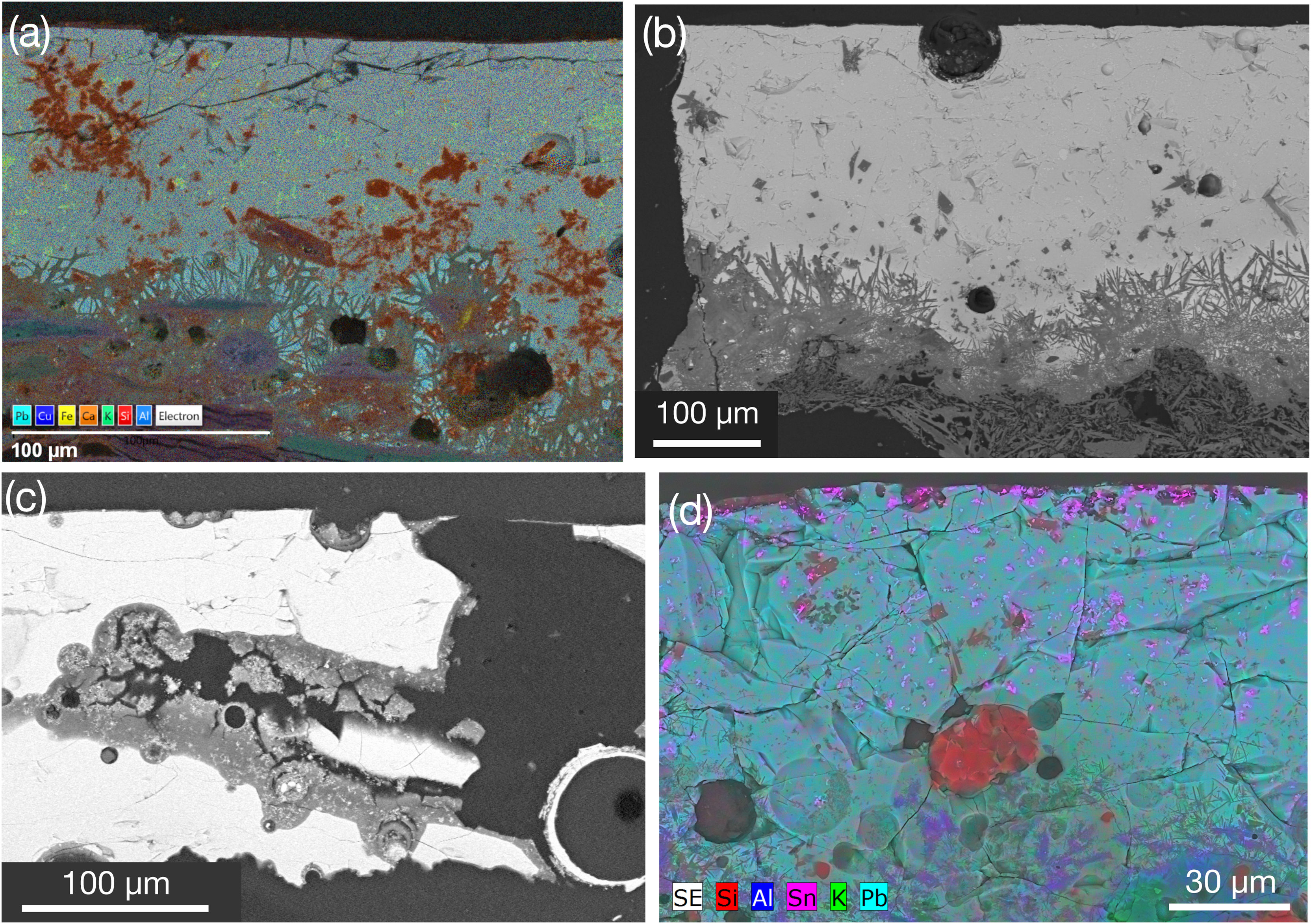

Weathered sebka glaze 132766_BL (150μm thick) exhibits cracking and bubbles with walls coated with neoformed SiO2-rich Al–Ca minerals (Fig. 5a and b). Large bubbles suggest a relatively low-viscosity glass phase promoting evacuation of gas-filled bubbles formed by the intense degassing of the ceramic body [11]. Well-defined glaze–ceramic interface is K-enriched (Fig. 5e) and Si depleted, likewise A085786/38_BL, which according to Ref. [8] indicates a once-firing process. Weathering progressed along the interface, leading to Pb depletion and P enrichment (Fig. 5c and d) that does not correspond with the K-enriched layer (Fig. 5e). K interface enrichment and thin K–Pb acicular feldspars (Fig. 5b) might suggest the use of a slip where the glaze mixture was applied over the already-fired ceramic body. Alternatively, as discussed above regarding the albite and Pb–Ca–P immiscible phase drops, likely indicate a physical interaction with the ceramic body enhanced by the low viscosity of the lead glass.

Furthermore, curved apatite crystals (Fig. 5d) are in the ceramic body, suggesting that some were incorporated into the glaze during firing. This hypothesis is supported by the rounded, immiscible Pb–Ca–P glaze phases located beneath the interface and within the glaze, frequently associated with bubbles (Fig. 5d). In Albanian 12th–13th century AD glazed ceramics P was added as both a flux and as modifying agent in green-ocean glazes [34]. Authors reported a crystallisation sequence involving apatite and related phosphate and arsenate minerals. Additional studies suggest that P may enhance the blue colour in Cu-based enamels [44]. Blue colour results from Co, Cu, Zn, and Fe dissolved within the glaze (Table 2). Notably, Ni – characteristic of 14th–15th century AD Valencian glazes [45] – was not detected in any of the studied 14th century AD blue glazes. Therefore, results suggest a chronological reassessment of these ceramics.

Green-turquoise glazeChemical compositionGlaze composition varies according to ceramic typology (Table 1 and Fig. 2) and location in the monument. However, all can be classified as lead tin-opacified glazes [2], although PbO is lower – for this classification – in 124965_GT, 121708_GT, and 2264_GT (Table 2). Green-turquoise glazes exhibit the highest variability in composition and some of the lowest PbO contents of all studied glazes (except for black glazes). The highest SnO2 quantity is found in the sebka glaze (132766_GT, 8.22wt.%), followed by the 13th century AD tile glazes (6.10 and 6.97wt.%). Notably, SnO2 in glaze 2264_GT is quite low (0.47wt.%). SnO2 levels are higher than in other green-turquoise glazes from the Alhambra [28]. Alkali elements are below 5wt.%, with Na more abundant than K (Table 2). This quantity is lower than in analogous Alhambra glazes [28], but higher than in some Mudejar architectural ceramics [17,39].

Green-turquoise colour results from Cu (expresses as CuO, Table 2) dissolved in the matrix under oxidising conditions. The highest CuO content (3.50wt.%) is found in the sebka glaze (132766_GT). Contrary to other Alhambra turquoise glazes, no Co is found in these glazes, though Fe is detected. Copper is present in oxidising environments as Cu2+ or Cu+, producing colours from bottle green to turquoise [6,44]. Hue depends on the Pb and alkali glaze contents. Green-turquoise colours occur in glazes with PbO <45wt.%, as found here (Table 2), except for A085786/19_GT (47.31wt.%) and 132766_GT (50.87wt.%). These glazes are not alkali-rich, unlike previously studied turquoise glazes [28].

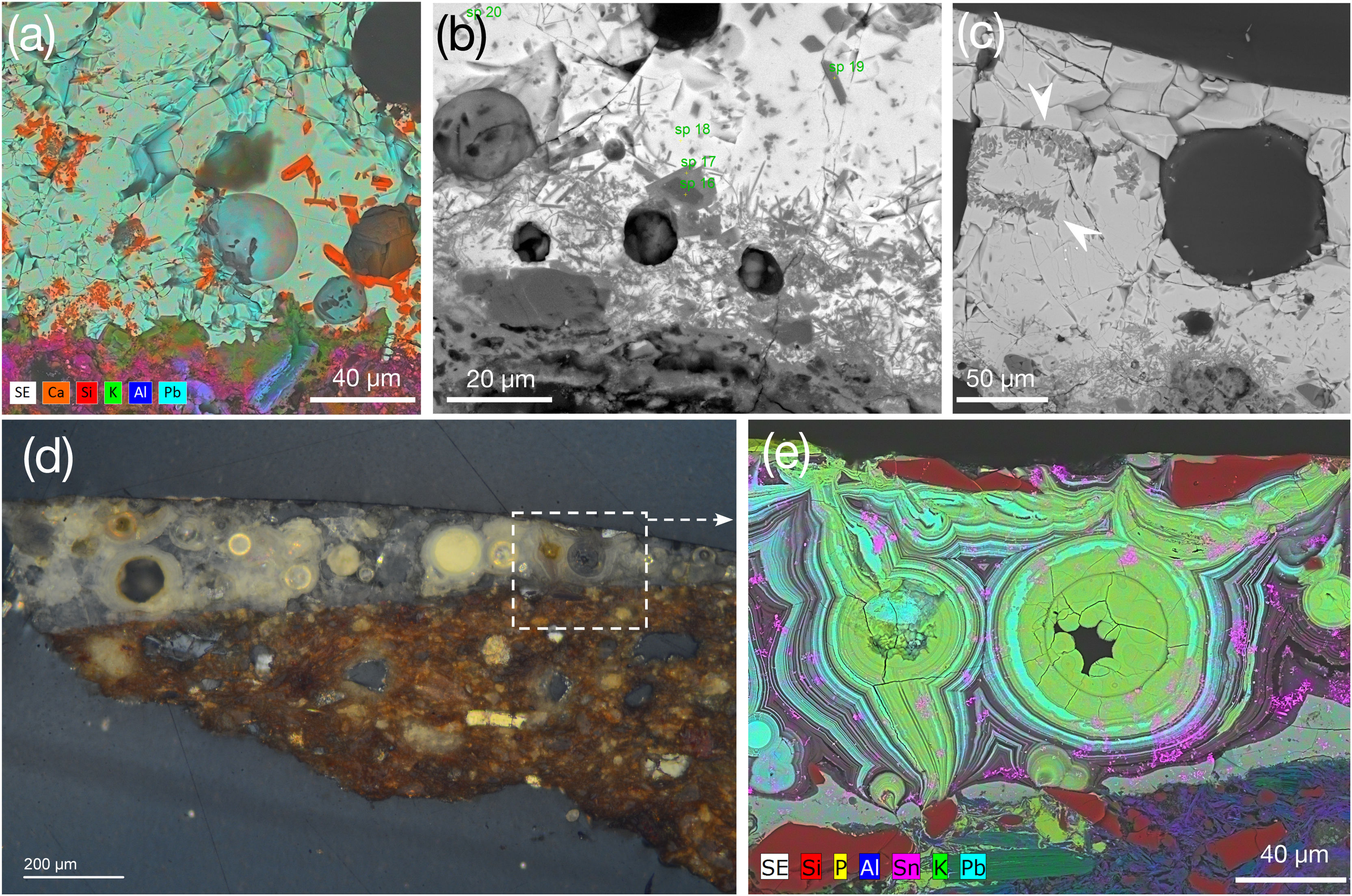

Microstructure and morphological featuresSEM investigation (Fig. 6) of green-turquoise glazes reveals variations in microstructure, composition, and firing processes. Glazes 121708_GT (90μm thick) and A085786/19_GT (320μm thick) exhibit pitting, bubbles, and fissures (Fig. 6a and b). Aggregated cassiterite crystals are found in the glazes, and wollastonite is abundant. The glaze–ceramic interface contains K-rich acicular crystals, suggesting a single-firing process. Glaze 124965_GT (210μm thick) exhibits a homogeneous glaze without evidence of weathering. The interface is clean indicating double-firing process.

Green-turquoise glaze. (a) X-ray map of 121708_GT showing wollastonite precipitates in brown-red. (b) BSE image of A08578619_GT exhibiting K–Pb feldspar crystals in the interface, (c) BSE image of 132766_GT displaying intense weathering, (d) X-ray map of 2264_GT showing rounded quartz (red), cassiterite (pink) and wollastonite (bluish) precipitates.

The sebka glaze 132766_GT (220μm thick) exhibits surface pitting, and early-stage banding where P was detected (Fig. 6c). Glaze 2264_GT (220μm thick) displays cracked and pitted surface with abundant medium-sized bubbles (Fig. 6d). Aggregated cassiterite and wollastonite precipitates are abundant. Wollastonite contains Cr (up to 0.8wt.% Cr2O3, spectrum 45, Table S4), which probably contribute to the green colour. Notably, the composition and microstructure of the dark green-turquoise 2264_GT glaze differs substantially from the others.

Black glazeAll black glazes originate from tiling mosaic panels (Tables 1 and 2) and contain no SnO2.

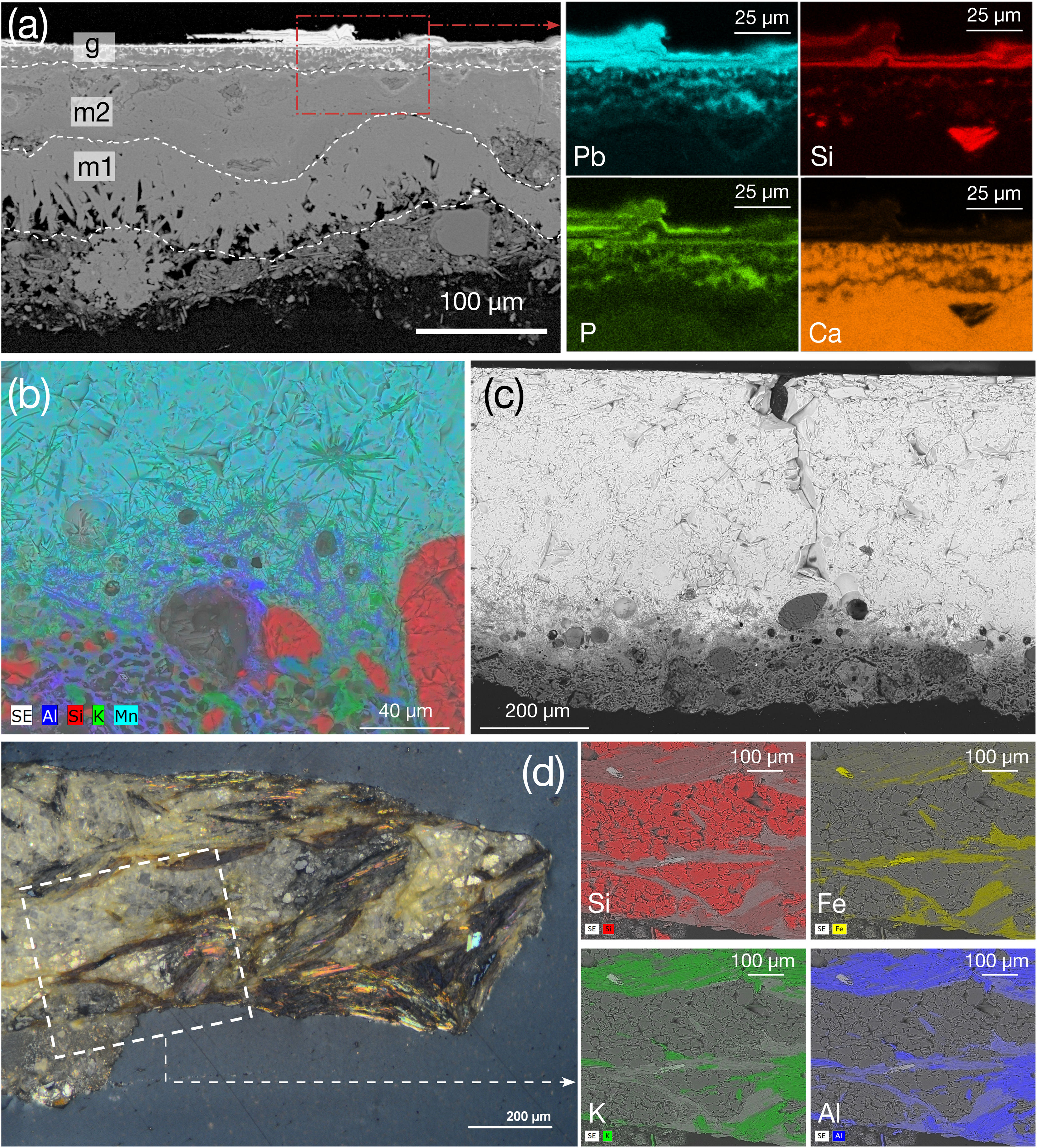

13th century AD glazesGlaze 91288_BK is unique, as it is not in contact with the ceramic body. This ceramic has never undergone intervention. SEM-BSE study revealed that the black decoration was applied over a Ca-rich layer (∼150μm thick) consisting of two parts: 91288_BK_m1 and 91288_BK_m2 (Fig. 7a). The lower part (91288_BK_m1) shows dissolution processes and precipitation that results in elongated crystals exceeding 50μm in length, near the interface with the ceramic body, made solely of Ca, likely in the form of lime – Ca(OH)2 – or calcite – CaCO3 –. EDS analyses show composition in wt.% oxides; thus, Ca is shown as CaO, though Ca may be part of other minerals, e.g., calcite or apatite.

Textures seen in black coloured samples (a) BSE image of 91288_BK showing large prismatic crystals in the lower layer (m1) perpendicular to the interface. Another lime-rich layer (m2) between layer m1 and the glaze (g). The area highlighted in dashed red lines correspond to the X-ray maps for Pb, Si, P, Ca on the right, (b) X-ray map of 2264_BK displaying K–Pb feldspar at the interface, (c) BSE image of 2264_BK showed in (b) illustrating a well-developed interface, (d) cross-polarised OM image of the black coloured ceramic 1382_BK exhibiting biotite, mica flakes and quartz aggregates (X-ray maps are showed at the right and highlighted in (d)).

The upper part (91288_BK_m2) contains CaO (72.12wt.%) and PbO (21.19wt.%, Table 2). High Pb levels at the top of 91288_BK_m2 are associated with a short (ca. 30μm) diffusion process between the glaze (bright colour in surface in Fig. 7a) and the Ca-rich substrate due to weathering. Glaze 91288_BK_g is exceptionally thin (ca. 25μm) and exhibits extensive weathering. This results in chemically alternating skinny layers that caused variations in Si–Pb–P parallel to the surface (Fig. 7a). Dark colour is due to Mn (MnO up to 15.01wt.%, Table 2) in the outermost layer of 91288_BK_g. This layer has the lowest SiO2 content (7.14wt.%) and the highest PbO content (65.24wt.%) among all studied glazes. Vanadium related to burial processes [31] was also detected.

The alternating Si–Pb–P layers are interpreted as corrosion features, termed lamellae [46]. Lamellae form due to ion exchange between the glaze and an aqueous fluid, leading to Pb and alkali metals diffusion from the glaze into the aqueous solution [46]. This process increases the pH at the glaze-fluid interface, liberating SiO2 into the aqueous phase as silicic acid while hydrous components incorporate into the glaze. Probably, weathering of glaze 91288_BK is related to post-depositional transformations in a wet environment after burial and aligns with the high P and Pb concentration [31]. Precipitation of fine-grained secondary phases due to the post-burial process cannot be excluded. Indeed, Ca, Fe, and Al associated with P might correspond to tiny secondary minerals previously identified [31,47,48], e.g. vivianite (Fe3(PO4)2·8(H2O)), mitridatite (Ca2Fe3(PO4)3O2·3(H2O)), crandallite (CaAl3(PO4)2(OH)5·(H2O)) and pyromorphite (Pb5(PO4)3Cl). However, Cl could not be identified (2.62keV in EDS spectra) because high Pb amount that has several lower-intensity M-lines that overlap in this region. Vanadium suggests the occurrence of vanadinite (Pb5(VO4)3Cl).

14th century AD glazesThe two studied glazes are significantly different. Glaze 2264_BK is thick (480μm) and exhibits scarce bubbles but extensive crazing (Fig. 7b and 7c). Colour is due to Mn (MnO 4.74wt.%) and iron expressed as Fe2O3 (4.08wt.%, Table 2). Its glaze–ceramic interface is thick and diffuse (∼100μm), characterised by Mn depletion, Al and K enrichment and acicular crystals (Fig. 7c) suggesting a single-firing process [7,35]. Crystal's composition corresponds to K-feldspar and diopside, unlike acicular minerals in the interface of other studied glazes composed of K–Pb feldspar.

Surprisingly, OM investigation of sample 1382_BK reveals that is not a glaze (Fig. 7d). EDS analyses are compatible with quartz, muscovite, and biotite (K(Mg,Fe)3AlSi3O10(OH,F)2) crystals, suggesting a fine-grained mica-schist or slate are present, both abundant in the nearby Sierra Nevada Mountain range (Granada). Black colour is likely due to the colour of Fe-bearing biotite and/or the presence of graphite. This finding demonstrates that Nasrid tile-makers possessed the technical skills to cut and polish these rock fragments to a thickness of ∼300μm. The method by which these fragments were integrated into the ceramic body remains uncertain, as they could not have been fired in the kiln simultaneously with the raw clay. Considering the firing temperatures attained by ceramic bodies of Nasrid architectural ceramics, ca. 950°C [28], significant mineralogical and textural changes would have occurred in the metamorphic rock (not observed in the studied sample), i.e., decomposition of micas, possible oxidation of graphite or iron, and potential vitrification of feldspars. These transformations could render the rock more brittle and alter its colour and texture. Therefore, the petrographic study suggests that the ceramic body was fired separately to the decoration. Possibly the rock fragments were shaped, polished, and applied to the ceramic surface post-firing, using mechanical embedding technique (inlaid into pre-prepared recesses on the surface) or adhesives. Like this, tile-makers would have preserved the metamorphic rock appearance while ensuring its integration into the mosaic. Indeed, the substrate of sample 1382_BK, directly beneath the rock fragments, is enriched in carbonates. This suggests that the Nasrid artisans may have used a mortar to adhere the fragments to the ceramic body of the tiling mosaic panel.

Honey glazeThe 14th century AD studied honey glazes were taken from the sampled tiling mosaic panels decorated in white and black (Fig. 2). Although honey glazes are compositionally similar, each glaze shows peculiarities related to weathering and microstructure.

Glaze 1382_H (thickness ∼150μm) shows bubbles (>50μm), crazing and weathering (Fig. 8a). Phosphorus was detected in the glaze matrix. Large bubbles suggest degassing from the ceramic body [11]. Wollastonite prismatic crystals are frequent, alike similar coloured glaze in Ref. [17], and evenly distributed throughout the glaze, while SnO2 precipitates are less frequent (Fig. 8a). It is known that wollastonite may incorporate impurities such as Fe, K, Mn, Mg, or Na. However, here Cr was detected (0.64wt.% Cr2O3, spectrum 12, Table S4), resembling those found in the Cr-bearing wollastonite from the green-turquoise glazes.

Honey glazes. (a) X-ray map of 1382_H showing wollastonite prismatic crystals (orange), (b and c) BSE image of 2264_H2 displaying large bubbles and wollastonite crystals (white arrows), (d) cross-polarised OM image of 2264_H1 highlighting the area of the X-ray map showed in (e) with Liesegang rings, cassiterite (pink) and quartz-rich bodies (red).

It could be argued that Cr comes from pigment chrome yellow, whose natural form is the mineral crocoite (PbCrO4). It was first used in 1818, and employed in ceramics, varnishes, and high-temperature paints [49,50]. If chrome yellow was used in glaze 1382_H, it will indicate that this piece was produced and incorporated into the mosaic panel during the 19th century AD onward, though no documentation exists. Honey colour probably results from Fe3+ (3.15wt.% Fe2O3, Table 2) fired in an oxidising atmosphere. Another particularity of this glaze is the association of Fe with Ti (expressed as TiO2 at 0.22wt.%, Table 2) similarly as in the black glaze of the same mosaic panel (1382_BK). Glaze–ceramic interface is sharp, with no K–Pb feldspars, suggesting double-firing and supporting the hypothesis that this piece was involved in a restoration.

Two honey glaze samples from the mosaic panel 2264 (Fig. 2), exhibiting distinct hue, were studied. Glaze 2264_H2 is ∼200μm thick, contains large bubbles (∼90μm) and elongated euhedral Cr-bearing wollastonite crystals (Fig. 8b and c, indicated by arrows), as in glaze 1382_H. However, unlike 1382_H, barium (Ba) together with scarce Fe was detected in 2264_H2, both dissolved in the glaze and in Ca–K–feldspar crystals (in Fig. 8b; spectrum 629, Table S4). These features are unique to glaze 2264_H2 and, along with the Cr-bearing wollastonite in the green-turquoise glaze of the same piece (2264_GT, spectrum 45, Table S4), suggest that both glazes may have been produced in the 19th or 20th century AD. Nonetheless, Ba may also derive from burial environments [31,49]. The thick interface of 2264_H2, rich in K–Pb feldspars, suggests a once-firing process, unlike sample 1382_H.

Glaze 2264_H1 (thickness ∼80–240μm, Fig. 8d) exhibits extensive weathering, showing Liesegang rings made of alternating Sn and Pb (Fig. 8e). Glaze shows agglomerated dendritic SnO2 crystals – that do not support the use of glaze fritting technique [37]– and elongated quartz-rich bodies near surface (Fig. 8e). Additionally, Ca/Pb-rich phosphates were identified. P correlates to Ca, attesting for Ca-phosphate minerals, locate in microcracks and reach the glaze–ceramic interface.

ConclusionsAnalysed glazes show chemical and microstructural variability related with colour and ceramic typology; however, all correspond to lead tin-opacified glazes. Microstructural features, e.g., glaze–ceramic interfaces, and acicular K–Pb feldspars occurrence, indicate that single-firing processes were dominant. Frequent bubbles, diffusive elemental profiles, and immiscible crystalline phases support this conclusion. Glazes were elaborated at low temperature (∼900°C) in an oxidising atmosphere. Often, quartz inclusions are present in glazes; rather than considering a process of glaze double opacity, the high cassiterite amounts of glazes suggest that quartz was added to improve glaze viscosity. Phosphorus associated with burial weathering was identified. Furthermore, in some white and blue glazes, P is related to the use of bone fragments or ashes. This addition was likely intended to enhance glaze emulsification rather than to serve as an opacifier, given the cassiterite contents. The most significant inferences from this study are shown below.

While some white glazes are well preserved, others exhibited severe weathering characterised by Liesegang rings, alkali depletion, and P-rich corrosion phases. Such weathering complicates chemical glaze analysis and highlights the importance of burial environments in modifying glaze composition. Moreover, differences between Nasrid white glazes with less SiO2 and more PbO than those from Mudejar contexts (e.g., Real Alcázar of Seville) suggest regional and chronological distinctions in glaze technology.

Blue glazes are mainly coloured by dissolved Co, Cu, Zn, and Fe in the glaze. Notably, Ni – commonly present in 14th–15th century AD Valencian glazes – is absent, raising questions about the chronological attribution, based on stylistics studies, of certain analysed ceramics to the 14th century AD. The greenish hue of some blue glazes is associated with Cr-bearing wollastonite, possibly indicating deliberate compositional control. These findings (and others discussed in the text) suggest diverse recipes and sources for the chromophores, and occasionally, technical innovations specific to Muhammad V's court. Regarding the green-turquoise glazes, they exhibited a more complex chromophore system, with Cu as the principal chromophore and Cr-bearing wollastonite contributing to colour modulation.

Black glazes are distinguished by their lower PbO contents. Colour is due to Fe and Mn oxides dissolved in the glaze. A black decoration was identified as a polished micas-schist rock intentionally cut and set into the tile mosaic panel. Concerning the honey glazes, some may reveal interventions, considering the presence of Ba-bearing K-feldspars and Cr-bearing wollastonite. This is a hypothesis in line with historical records of restoration.

Finally, a more extensive study of compositional anomalies in glazes (e.g., presence/absence of Ba, Ni, Cr, V, etc.) would be required to assess issues related to chronology, late post-deposition weathering, or later ceramic interventions. These results also illustrate the power of combining chemical, microstructural, and contextual analysis, with historians and archaeologists’ knowledge to understand both ancient technological choices and modern conservation interventions in Islamic architectural ceramics.

FundingFunding was provided by Research Project PID2023-146405OB-100 of Ministry of Science Innovation and Universities (MICIU/AEI/10.13.039/501100011033,x), Research Group RNM-179 of Junta de Andalucía (Spain), and Research Excellence Unit “Science in the Alhambra” (UCE-PP2018-01) of University of Granada (Spain). M. Urosevic acknowledges funding through the Spanish PTA program (PTA2022-021516-I).

We thank the Alhambra and Generalife Council, and to Silvia Pérez and Eva Moreno from the Alhambra Museum's private storage, as well to María Elena Díez Jorge for providing critical insights into these ceramics. We acknowledge the constructive comments of the two anonymous reviewers, which have significantly contributed to improving the clarity and overall quality of the manuscript.

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

SEM images of the blue glaze A085786/38_BL. Above appears a BSE image displaying the minerals identified in the glaze, i.e. diopside – Di, wollastonite – Wo, Albite –Ab, and apatite – Ap. Below are shown the corresponding X-ray maps for Si, Ca, Mg, Al, Pb, P, Fe, K and Na. Note the large size subhedral diopside surrounded by dendritic wollastonite-diopside crystals that are intergrowth with apatite. Note also the rounded and elongated albite crystals in the glaze and in the ceramic body.