To analyze the frequency of reattendances in PC and their association with adverse events, considering sex-based differences.

DesignA retrospective observational study.

SiteFive primary care centres in the Valencia Region (Spain).

ParticipantsPatients over 50 years old attended in between 2019 and 2024.

Main measurementsA review of 541 electronic health records of patients was conducted to identify reattendances occurring within 20 days after an index visit Associated AEs were assessed as well.

ResultsA total of 2077 reattendances were recorded (0.77 per patient-year), with significantly higher frequency among men (1601 in men vs. 476 in women; P<0.001). Eighty-five AEs were identified (annual incidence: 3.1; 95% CI: 2.5–3.8), with women experiencing an 18% higher incidence compared to men (OR=1.18; 95% CI: 1.13–1.24; P<0.001). No significant sex-based differences were observed in the severity of harm (P=0.713). Reattendances were associated with AEs (OR=7.04; P<0.001), as was cognitive impairment, measured using the Pfeiffer Index (OR=1.21; P=0.033). In contrast, low and medium PC utilization were associated with a lower probability of AEs (OR=0.22 and 0.45; P=0.003 and 0.043, respectively).

ConclusionsReattendances in PC are frequent and significantly associated with the occurrence of preventable AEs. Sex-based differences and individual patient factors, such as cognitive status and care utilization patterns, should be considered in patient safety strategies.

Analizar la frecuencia de las re-atenciones en atención primaria y su asociación con eventos adversos, considerando las diferencias según el sexo.

DiseñoEstudio observacional retrospectivo.

ÁmbitoCinco centros de atención primaria en la Comunidad Valenciana (España).

ParticipantesPacientes mayores de 50 años atendidos entre 2019 y 2024.

Mediciones principalesSe revisaron 541 historias clínicas electrónicas de pacientes para identificar re-atenciones ocurridas en los 20 días posteriores a una visita índice. Se evaluaron también los eventos adversos asociados.

ResultadosSe registraron un total de 2.077 re-atenciones (0,77 por paciente/año), con una frecuencia significativamente mayor en los varones (1.601 en varones frente a 476 en mujeres; p<0,001). Se identificaron 85 eventos adversos (tasa de incidencia anual: 3,1; IC 95%: 2,5-3,8), con una incidencia del 18% mayor en las mujeres en comparación con los varones (OR=1,18; IC 95%: 1,13-1,24; p<0,001). No se observaron diferencias significativas según el sexo en cuanto a la gravedad del daño (p=0,713). Las re-atenciones se asociaron con la ocurrencia de eventos adversos (OR=7,04; p<0,001), al igual que el deterioro cognitivo, medido mediante el índice de Pfeiffer (OR=1,21; p=0,033). En cambio, una utilización baja o media de la atención primaria se asoció con una menor probabilidad de eventos adversos (OR=0,22 y 0,45; p=0,003 y 0,043, respectivamente).

ConclusiónLas re-atenciones en atención primaria son frecuentes, y se asocian de forma significativa con la ocurrencia de eventos adversos prevenibles. Las diferencias según el sexo y los factores individuales del paciente, como el estado cognitivo y el patrón de utilización de servicios, deben tenerse en cuenta en las estrategias de seguridad del paciente.

It is estimated that 12.6% of patients in primary care (range: 2.3–26.5%)1 experience a safety incident (that could have caused or did cause harm). The incidence of adverse events (AEs), defined as incidents that result in harm, per 1000 consultations ranges between 2.1% and 6.0%, with higher risk among patients aged 65 and older.2–4 In Spain, it has been estimated that 10.6 AEs occur annually per family physician.5 The APEAS study (Study on Patient Safety in Primary Health Care)6 found one AE every 10 consultations (incidence: 11.18 per thousand), with 70% considered preventable. In a more recent study, also based on medical record review (2020),7 7.6% (95% CI: 6.4–8.8%) of adult patients and 5.7% (95% CI: 3.9–7.5%) of paediatrics patients experienced an AE. Additionally, 17.6% of adult patients and 13.7% of paediatric patients (as reported by their parents) reported having suffered an AE during healthcare.8

Reattendances and patient safetyReattendances (repeat visits within 7–20 days for the same health issue) are considered an indicator of healthcare quality and patient safety, particularly in the evaluation of emergency services.9,10 In primary care, reattendances are also a useful trigger for identifying diagnostic errors, inappropriate treatments, delays in appropriate clinical action, and inadequate referrals, all of which may contribute to safety incidents and reflect suboptimal care.11

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to analyze the frequency of reattendances in PC and their association with AEs, as well as sex-based differences in these outcomes.

MethodsThis was a retrospective observational study based on the review of routinely collected data from electronic health records in PC in the Valencia Region (Spain). The STROBE guideline12 for cohort studies was adopted as a reference for reporting this study.

DefinitionsAn AE was defined as unexpected and unintentional harm suffered by a patient during healthcare, not related to the underlying disease.13

Reattendance was defined as any consultation occurring within 20 days after the index visit for the same health problem,14 including visits related to urgent, or wound care procedures in PC.

Health centresPC professionals (physicians and nurses) from five health centres participated in the study. These centres were randomly selected from two healthcare departments, one located in Alicante and the other in Valencia.

ReviewersA total of 19 reviewers participated in the study. They were staff members from the participating health centres and voluntarily collaborated with the aim of improving the quality of care provided to patients. All were PC professionals with a minimum of 10 years of experience. A one-hour training session was conducted for all reviewers to familiarize them with the procedure, review two simulated cases, and resolve any questions. A third simulated case was reviewed to ensure consistent application of the instructions. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Kappa statistic, and no additional training sessions were deemed necessary.

MaterialsData coding was carried out by each reviewer using a custom-designed digital template created specifically for this study. A pilot test was conducted to ensure the functionality and clarity of the data collection tool. The platform allowed structured entry of data for each study variable. A call centre, managed by the ATENEA research group, was available throughout the study period to resolve technical issues and provide support.

Medical recordsA sample size of 570 medical records was estimated to detect a reattendance proportion of approximately 38%, with a 95% confidence level and a 4% margin of error. A simple random selection (k=3) was used to extract the records of patients who had attended PC consultations, until each reviewer completed their assigned cases.

Inclusion criteria: Patients over 50 years of age who, within the last five years, had attended a PC consultation. Exclusion criteria: Patients residing in nursing homes, shelters, or in transitional situations. Patients whose index visit occurred in a hospital setting were excluded.

In cases of incomplete records, the affected patient was replaced by another randomly selected case from the same pool.

Review periodData were collected from patient records corresponding to visits between April 1, 2019, and March 30, 2024. The review of these medical records was carried out between September 12 and December 13, 2024.

ProcedureEach reviewer first extracted a list of potential cases using the Alumbra digital application. Alumbra is a clinical data engine implemented in the primary care centres involved in this study, designed to identify electronic health records that match predefined selection criteria. In this study, records were selected based on consultations in primary care related to the following ICD-10 codes: diabetes (E11.9), hypertension (I10), asthma (J45.909), diabetic foot ulcer (E11.622), skin ulcer (E11.621), and abscess (L2). Additionally, records were selected based on NANDA codes related to specific nursing diagnoses, including: 00002, 00232, 00233, 00234, 00103, 00179, 00178, 00296, 00016, 00322, 00011, 00015, 00012, 00235, 00236, 00013, 00196, 00197, 00204, 00267, 00291, 00200, 00201, 00228, 00004, 00266, 00045, 00039, 00206, 00048, 00219, 00277, 00261, 00303, 00035, 00245, 00250, 00087, 00220, 00247, 00086, 00038, 00213, 00312, 00304, 00205, 00046, 00047, 00036, 00100, 00246, 00044, 00248, 00132, 00133, and 00255.

The selected patient sample included approximately equal numbers of men and women. A simple random sampling procedure was then applied to this pool to extract the final set of medical records. These records were subsequently reviewed, and the requested data were entered into a custom digital platform designed for the study. All information was recorded in a fully anonymized manner.

VariablesThe following variables were coded: age, sex, family structure (whether the person lived alone, with a partner, or with other people in the household), employment status, number of daily medications, main diagnosis, comorbidities, use of harmful substances (tobacco, alcohol), Barthel Index, Pfeiffer Index, officially recognized degree of dependency (if applicable), number of PC physician and nurse visits in the last year, number of wound care visits in the last five years, number of reattendances within 20 days related to the index wound care visit, number of urgent primary care visits in the last five years, number of reattendances for the same reason within 20 days of the index consultation, number of referrals to hospital specialists in the last five years, number of days between the index consultation and the specialist appointment, number of missed appointments with PC physicians and nurses in the last five years. If harm occurred because of the reattendance or delay, it was assessed using the classification and severity scale by Woods et al.15

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used, with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean, median, standard deviation) for continuous variables. To compare groups, Chi-squared tests (with Yates correction when necessary) were applied for categorical variables, the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Z-test for proportions was utilized when comparing proportions. A Poisson regression model was used to compare adverse event incidence rates between men and women. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with reattendance and the occurrence of adverse events. In both cases, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated. Variable selection was performed using the backward elimination method for both regression models. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 (two-sided) for all tests. Analyses were conducted using the R programming language (v.4.4.2).

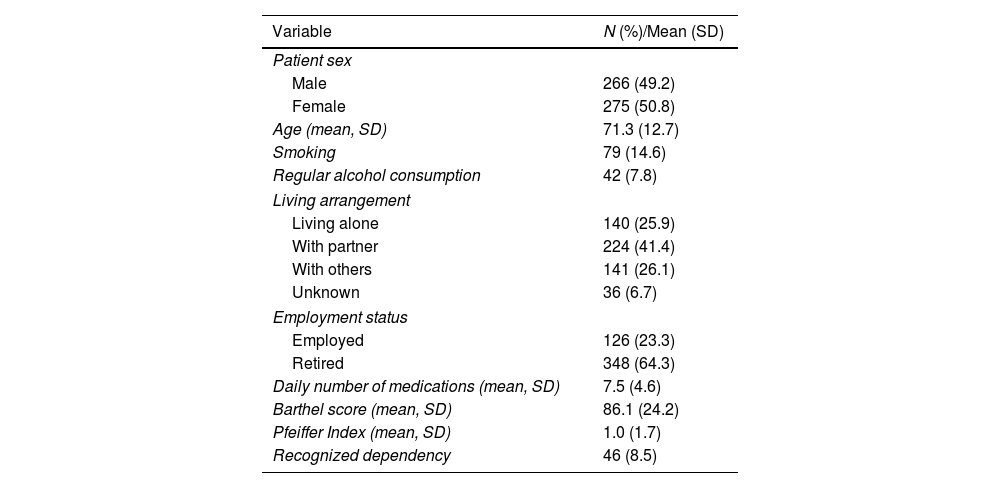

ResultsA total of 541 medical records from patients attended in the public healthcare system were reviewed. Patients ranged in age from 19 to 102 years, with 275 (50.8%) being women. The most frequent primary diagnosis was type 2 diabetes mellitus, present in 269 patients (48.9%), followed by arterial hypertension (94 patients, 17.1%). Other conditions such as heart failure (14, 2.5%), asthma (13, 2.4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9, 1.6%), and hypercholesterolemia (8, 1.5%) showed lower prevalence.

The most common comorbidity was arterial hypertension (136 patients, 24.7%), followed by hypercholesterolemia (80, 14.5%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (59, 10.7%), atrial fibrillation (45, 8.2%), anxiety (42, 7.6%), and obesity (37, 6.7%). The patient with the highest number of daily medications was taking 26 drugs (Table 1).

Description of the patient sample reviewed.

| Variable | N (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Patient sex | |

| Male | 266 (49.2) |

| Female | 275 (50.8) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 71.3 (12.7) |

| Smoking | 79 (14.6) |

| Regular alcohol consumption | 42 (7.8) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Living alone | 140 (25.9) |

| With partner | 224 (41.4) |

| With others | 141 (26.1) |

| Unknown | 36 (6.7) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 126 (23.3) |

| Retired | 348 (64.3) |

| Daily number of medications (mean, SD) | 7.5 (4.6) |

| Barthel score (mean, SD) | 86.1 (24.2) |

| Pfeiffer Index (mean, SD) | 1.0 (1.7) |

| Recognized dependency | 46 (8.5) |

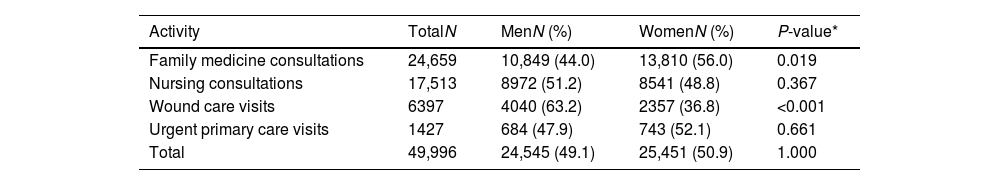

Table 2 shows the volume of healthcare utilization among patients whose records were reviewed. During the study period, women attended more family medicine consultations than men, whereas men required a higher number of nursing wound care visits (see Table 3). Over the five-year period, the average number of visits per patient per year was 9.1 for family medicine and 6.5 for primary care nursing.

Total number of primary care consultations over the past 5 years (N=541).

| Activity | TotalN | MenN (%) | WomenN (%) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family medicine consultations | 24,659 | 10,849 (44.0) | 13,810 (56.0) | 0.019 |

| Nursing consultations | 17,513 | 8972 (51.2) | 8541 (48.8) | 0.367 |

| Wound care visits | 6397 | 4040 (63.2) | 2357 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| Urgent primary care visits | 1427 | 684 (47.9) | 743 (52.1) | 0.661 |

| Total | 49,996 | 24,545 (49.1) | 25,451 (50.9) | 1.000 |

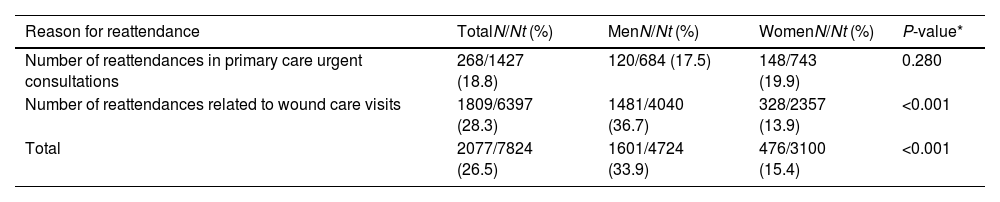

Reattendances over the 5-year period (N=541).

| Reason for reattendance | TotalN/Nt (%) | MenN/Nt (%) | WomenN/Nt (%) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of reattendances in primary care urgent consultations | 268/1427 (18.8) | 120/684 (17.5) | 148/743 (19.9) | 0.280 |

| Number of reattendances related to wound care visits | 1809/6397 (28.3) | 1481/4040 (36.7) | 328/2357 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Total | 2077/7824 (26.5) | 1601/4724 (33.9) | 476/3100 (15.4) | <0.001 |

N: total number of reattendances; Nt: total number of appointments.

The overall consultation frequency between men and women was similar for the study period (P-value=0.079) (Table S1, Supplementary Material). The mean number of missed appointments with the family physician during this period was 1.7 (SD 5.9), and 2.1 (SD 5.2) for nursing appointments.

The average number of days between the index consultation that led to a referral and the actual appointment with the hospital specialist was 48.5 days (SD 96.7). The average number of hospital admissions over the last five years was 1 (SD 1.6) per patient, of which 0.3 (SD 0.9) were initiated in primary care.

ReattendancesOver the 5-year study period, a total of 2077 reattendances were recorded among the 541 patients (mean per patient per year: 0.77; 95% CI [0.73–0.80]), related to urgent care and wound care provided by primary care nurses. A total of 1601 reattendances occurred among male patients (1.20 per patient per year) and 476 among female patients (0.35 per patient per year) (P-value<0.001) (Table 3). These reattendances were mainly due to the combination of diverse causes (166, 30.7%), underestimation of the severity of the problem (102, 18.8%), inadequate treatment plans (90, 16.6%), and lack of access to the appropriate resource (78, 14.4%) (Table S2, Supplementary Material).

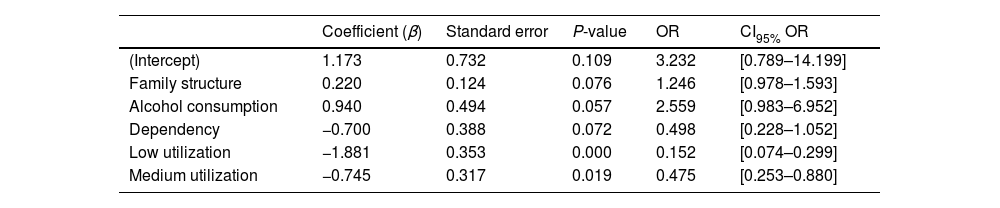

Factors associated with reattendancesLower PC utilization was associated with a lower number of reattendances (OR 0.152, 95% CI [0.074–0.299], P-value=0.000), suggesting that patients with low utilization have an 84.8% lower likelihood of reattendances compared to those with high utilization. Similarly, patients with medium utilization also showed a lower number of reattendances (OR 0.475, 95% CI [0.253–0.880], P-value=0.019), indicating a 52.5% reduction in the likelihood of reattendances (Table 4).

Logistic regression: factors associated with the likelihood of reattendance in PC (N=541).

| Coefficient (β) | Standard error | P-value | OR | CI95% OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.173 | 0.732 | 0.109 | 3.232 | [0.789–14.199] |

| Family structure | 0.220 | 0.124 | 0.076 | 1.246 | [0.978–1.593] |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.940 | 0.494 | 0.057 | 2.559 | [0.983–6.952] |

| Dependency | −0.700 | 0.388 | 0.072 | 0.498 | [0.228–1.052] |

| Low utilization | −1.881 | 0.353 | 0.000 | 0.152 | [0.074–0.299] |

| Medium utilization | −0.745 | 0.317 | 0.019 | 0.475 | [0.253–0.880] |

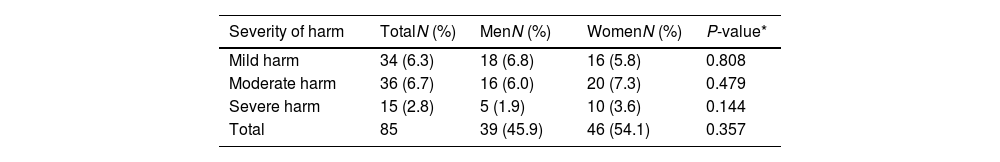

In total, across the 541 patients over the 5-year period, 85 AEs were identified, with an incidence rate of 3.1 AEs per patient per year (95% CI [2.5–3.8]). Of the total AEs, 39 were detected in men (incidence: 2.9 AEs per patient per year) and 46 in women (incidence: 3.3 AEs per patient per year), indicating that women had an 18% higher incidence of AEs compared to men (Coefficient β 0.165, OR 1.180, IC95% [1.128–1.235], P-value<0.001). The severity of the harm experienced by patients was similar between men and women (P-value=0.713) (Table 5).

Frequency of AEs and severity of harm according to the Woods Scale (N=85).

| Severity of harm | TotalN (%) | MenN (%) | WomenN (%) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild harm | 34 (6.3) | 18 (6.8) | 16 (5.8) | 0.808 |

| Moderate harm | 36 (6.7) | 16 (6.0) | 20 (7.3) | 0.479 |

| Severe harm | 15 (2.8) | 5 (1.9) | 10 (3.6) | 0.144 |

| Total | 85 | 39 (45.9) | 46 (54.1) | 0.357 |

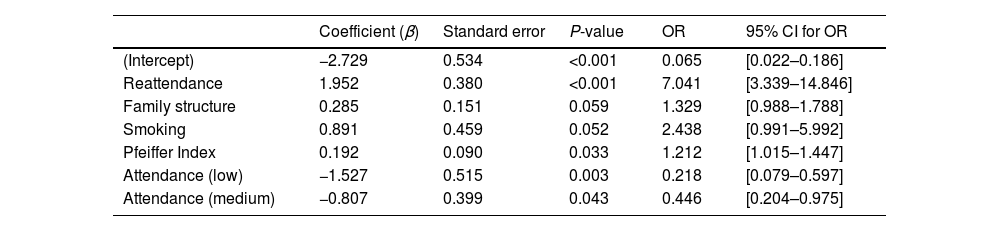

Patients with reattendances were seven times more likely to experience an AE (OR=7.041, P-value<0.001). Cognitive impairment, measured using the Pfeiffer Index, also showed a significant association: each one-point increase in the index was associated with a 21.2% higher probability of experiencing an AE (OR=1.212, P-value=0.033). Conversely, individuals with low (OR=0.218, P-value=0.003) and medium (OR=0.446, P-value=0.043) levels of PC attendance had 78.2% and 55.4% lower odds, respectively, of experiencing an AE compared to those with high attendance. This suggests that lower frequency of PC visits may act as a protective factor against safety incidents (Table 6).

Logistic regression: factors associated with the probability of experiencing an AE.

| Coefficient (β) | Standard error | P-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −2.729 | 0.534 | <0.001 | 0.065 | [0.022–0.186] |

| Reattendance | 1.952 | 0.380 | <0.001 | 7.041 | [3.339–14.846] |

| Family structure | 0.285 | 0.151 | 0.059 | 1.329 | [0.988–1.788] |

| Smoking | 0.891 | 0.459 | 0.052 | 2.438 | [0.991–5.992] |

| Pfeiffer Index | 0.192 | 0.090 | 0.033 | 1.212 | [1.015–1.447] |

| Attendance (low) | −1.527 | 0.515 | 0.003 | 0.218 | [0.079–0.597] |

| Attendance (medium) | −0.807 | 0.399 | 0.043 | 0.446 | [0.204–0.975] |

Reference category for attendance: high attendance.

This study suggests that reattendances in PC can be more frequent than previously assumed and warrant the same level of attention as in other healthcare settings, particularly due to their association with AEs and, ultimately, with suboptimal care. In our cohort, nearly one in four reattendances occurred following wound care or urgent consultations, and their occurrence was significantly linked to the development of preventable AEs. These findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that repeat consultations may act as effective triggers for identifying diagnostic errors, inappropriate treatments, delays in clinical action, and system-level deficiencies in continuity and coordination of care.16,17

Although men accounted for a significantly higher number of reattendances, especially following wound care provided by nurses, women experienced an 18% higher incidence of AEs. Notably, there were no significant sex-based differences in the severity of harm. This paradox may reflect a broader issue related to gender bias in healthcare. Previous research has shown that gender, as a social construct, influences health behaviours, access to and use of health services, and the healthcare system's responses.18,19 Gender bias, understood as a systematic error in the interpretation of symptoms and in the clinical decision-making process, can result in women receiving less timely or less appropriate care, despite higher consultation rates in family medicine. In our study, women consulted more frequently with family physicians, while men had more nursing wound care visits. However, the reasons behind the higher number of males receiving nursing wound care remain unclear. It is possible that women manage their own care more effectively or that gender-related differences in communication, clinical decision-making, and care planning play a role. One hypothesis is that men may be more frequently scheduled for follow-up visits, whereas women may receive verbal instructions for self-care. This potential bias in follow-up protocols may contribute to inequities in outcomes and warrants further investigation.

A particularly relevant finding of this study is the association between reattendances and the occurrence of AEs. Patients with a reattendance had a sevenfold increase in the odds of experiencing an AE, highlighting reattendance as a potential early indicator of patient safety risks. Additionally, cognitive impairment was independently associated with AEs, with each one-point increase in the Pfeiffer Index increasing the odds of harm by 21.2%. This aligns with earlier studies showing that patients with cognitive limitations are more susceptible to care coordination errors and treatment complications.20

Another contribution of this study is the observation that lower and medium levels of healthcare utilization were associated with a significantly reduced risk of both reattendances and AEs. Patients with lower utilization had lower odds of reattendance compared to those with high utilization. These findings suggest that high frequency of consultations may reflect underlying care complexity, multimorbidity, or system-level inefficiencies, all of which may increase vulnerability to safety incidents. Previous literature also supports this interpretation, as higher service use has been associated with fragmented care and greater exposure to potential errors.21,22

These findings should be interpreted within the context of Spain's public primary care system, characterized by team-based care, strong nursing involvement, and high accessibility, which may influence reattendance patterns and safety outcomes.

Practical implicationsOur results reinforce the value of monitoring reattendances as a practical strategy to detect safety risks and identify patients who may benefit from targeted interventions. Integrating sex-based analysis and individual patient factors, such as cognitive function and utilization patterns, may enable more tailored and equitable approaches to improving safety in PC settings. Moreover, efforts should be made to review care protocols—especially those related to nursing wound care, and to examine how gendered assumptions may influence clinical decision-making and follow-up procedures.

LimitationThis study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the selection of diagnoses based on ICD-10 and NANDA codes may have limited the identification of all relevant reattendances and AEs, potentially underestimating their true frequency. Second, the findings are limited to a sample of patients from five PC centres in two health departments within the Valencia Region. Therefore, generalization to the broader Spanish PC system or to other countries should be made with caution.

Third, the retrospective nature of the study and the reliance on existing electronic health records may have introduced information bias, especially regarding the documentation of AEs and their severity. Although reviewers were trained and inter-rater reliability was assessed, the subjective component involved in evaluating harm and preventability cannot be entirely ruled out.

Fourth, the final sample fell short of the estimated 570 records. Although the sample size obtained was acceptable this point could be considered when understanding the outcomes.

Fifth, in spite of the association between reattendance and AE observed, the retrospective design of the study prevents establishing a causal relationship. It must be considered when understanding the outcomes.

Finally, the definition of reattendance as any consultation within 20 days for the same problem, while consistent with previous literature, may have included follow-ups that were clinically appropriate, possibly inflating the association with AEs. Fifth, although efforts were made to ensure balanced sex distribution in the sample, potential residual confounding related to gender roles, health-seeking behaviour, or differential care practices could influence the observed differences.

ConclusionReattendances in primary care are more frequent than expected and are significantly associated with the occurrence of preventable adverse events (AEs). Sex-based differences are evident and warrant greater attention than they have received to date. Although the proportion of severe harm observed in our study was relatively low (ranging from two to ten cases), this aligns with national estimates and should not lead to an underestimation of the risks posed to patients. Importantly, the preventable nature of many of these events, along with their association with modifiable risk factors, underscores the need to implement preventive strategies—including approaches that actively involve patients.23

Ethical considerationsThe study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2024). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Sant Joan, the reference hospital for the Alicante-Sant Joan Health Department in Spain. The exemption from obtaining informed consent from each patient included in the study was applied in accordance with Article 58, paragraph 2, of Spanish Law 14/2007 on Biomedical Research, as this was an epidemiological study. Reviewers accessed only the medical records of patients assigned to the professional acting as reviewer.

FundingThis work has been supported by Project Prometeu 2021/061 granted by Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital, Generalitat Valenciana.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest that could have influenced the conduct of the study or the interpretation of its results.