This study describes the health education experiences of older adults with chronic disease (CD).

DesignA qualitative study employing a phenomenological approach.

SettingMunicipalities of Central Region of Cundinamarca Colombia.

ParticipantsThe study was conducted through face-to-face semi-structured interviews. A total of 40 older adults participated in the study.

MethodsData were collected through interviews, which were then coded and analyzed using ATLAS.ti software.

ResultsThe analysis revealed three main themes: Older adults became aware of their CD through initial signs and symptoms and reflections on previous lifestyle habits. After diagnosis, they managed CD through new activities and routines including pharmacologic treatment, health check-ups, and regular clinical tests. Treatment adherence was influenced by personal experiences and the adoption of new lifestyle habits.

ConclusionsThe changes experienced by older adults implied a learning process influenced by their individual history, experiences, and external factors like family support. The findings provide valuable insights for designing health education strategies aimed at improving the empowerment of older adults in their healthcare process.

Este estudio describe las experiencias de educación en salud de los adultos mayores con enfermedades crónicas (EC).

DiseñoEstudio cualitativo con enfoque fenomenológico.

LugarMunicipios de la Región Central de Cundinamarca, Colombia.

ParticipantesSe realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas individuales. Un total de 40 adultos mayores participaron en el estudio.

MétodosLa transcripción de las entrevistas fueron codificadas y analizadas utilizando el software ATLAS.ti.

ResultadosEl análisis reveló tres temas principales: los adultos mayores se dieron cuenta de su EC a través de signos y síntomas iniciales y reflexiones sobre hábitos de vida previos. Después del diagnóstico, manejaron la EC mediante nuevas actividades y rutinas que incluían tratamiento farmacológico, chequeos de salud y pruebas clínicas regulares. La adherencia al tratamiento fue influenciada por experiencias personales y la adopción de nuevos hábitos de vida.

ConclusionesLos cambios experimentados por los adultos mayores implicaron un proceso de aprendizaje influenciado por su historia individual, experiencias y factores externos como el apoyo familiar. Los hallazgos proporcionan valiosas ideas para diseñar estrategias de educación en salud destinadas a mejorar el empoderamiento de los adultos mayores en su proceso de atención médica.

Chronic noncommunicable diseases (CD) cause over 41million deaths a year; people between 30 and 69 years old are responsible for 71% of the total death toll worldwide, with a particularly high incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes mellitus.1 These facts represent a call for more attention to how older adults can participate in improving their health conditions. Health education represents a strategy to foster positive changes in older adults’ overall life quality. Therefore, health professionals should create strategies that consider the older adult's personal and social context to offer them opportunities to adopt healthy lifestyles.2

Older adults with CD assume an active role in their healthcare when they have the autonomy to control the disease's signs and symptoms. Other factors that contribute to this active role include understanding the medicine labels and nutritional indications, being aware of their current health condition, knowing how to communicate assertively with health professionals about their disease, and making decisions related to their health.3 These actions are the result of health literacy, or “the people's knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise and apply health information to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning health care, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course”.4 However, many older adults present a low health literacy level, which is evident in the limited use of health education initiatives, higher hospital admission, lower knowledge about CD, and problems related to physical and mental health.5,6 That is why, understanding the older adult's experience around CD health education is crucial to design initiatives that consider their needs and perspectives.

Health professionals can contribute to improving health literacy among older adults by creating health education strategies,1 such as tools for the development of emphatic and communicative competencies to interact assertively with older adults and their families6; ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) strategies to promote self-care, and support systems and care environments to impact how older adults act toward the improvement of their health condition,2 self-care, and disease treatment.5,6

In Colombia, South America, the percentage of older adults with CD is increasing, with higher rates of hypertension (60.1%), osteoarthritis (26.6%), and diabetes (18.1%). If this growing pace continues, Colombia could reach more than 2.1million people with CD by 2033; that is, a quarter (26.4%) of the total older adult population.1 Therefore, healthcare providers need to increase their skills in the health education process. To achieve this, it is necessary to know the experiences of older adults in health education. For this reason, this study aimed to describe the health education experiences of older adults with CD. This study provides an opportunity for understanding what resources are needed in health education and the health literacy needs of the older adult population.

MethodsThis study is grounded in qualitative research7 because it privileges the experience that occurs in natural settings. We utilized a phenomenological approach8 to understand the health education experiences of older adults with CD, such as hypertension, diabetes, EPOC, and arthrosis. Phenomenology focuses on the participants’ individual lived experiences of a phenomenon.

Participants were older adults (65 years old and older), with at least one year of a chronic disease diagnosis, and who were part of a public health chronic disease initiative in the Sabana Centro Colombian region. We included participants in rural and urban areas to cover a variety of needs and contexts. Exclusion criteria included older adults with recent surgery, hospitalization (in the last month), or people with cognitive disability that could hinder effective communication.

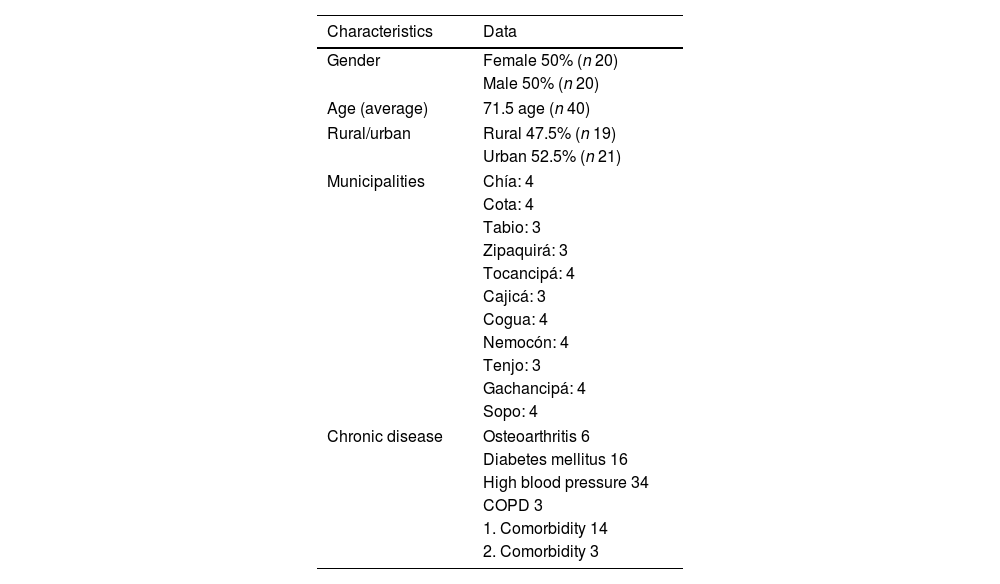

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews. The interview protocol was reviewed by an expert panel and piloted with a 65-year-old woman who has diabetes. Interviewers were trained by a qualitative research expert using the interview protocol and the phenomenological approach. Every interviewer conducted at least two mock interviews before interviewing the participants as part of the training.9 A total of 40 face-to-face interviews were conducted at the participant's home, or the health facility. In one municipality, the team had to conduct telephonic interviews because of the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine measures. Of the 40 participants of the study, 11 were accompanied by a caregiver or care partner during the interview. On average, interviews lasted 20min. All participants voluntarily participated in the study and signed a consent form. IRB approval for this study was obtained at a research university (IRB # 01115, June 2019). No withdrawals were reported. See Table 1 for more details about the participants.

Socio-demographic data.

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Gender | Female 50% (n 20) |

| Male 50% (n 20) | |

| Age (average) | 71.5 age (n 40) |

| Rural/urban | Rural 47.5% (n 19) |

| Urban 52.5% (n 21) | |

| Municipalities | Chía: 4 |

| Cota: 4 | |

| Tabio: 3 | |

| Zipaquirá: 3 | |

| Tocancipá: 4 | |

| Cajicá: 3 | |

| Cogua: 4 | |

| Nemocón: 4 | |

| Tenjo: 3 | |

| Gachancipá: 4 | |

| Sopo: 4 | |

| Chronic disease | Osteoarthritis 6 |

| Diabetes mellitus 16 | |

| High blood pressure 34 | |

| COPD 3 | |

| 1. Comorbidity 14 | |

| 2. Comorbidity 3 | |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary, 1. Comorbidity, two or more chronic diseases.

Convenience sampling included men and women from rural and urban areas of 11 out of the 12 municipalities of the Sabana Centro region. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed line by line. Data were stored in password-protected electronic devices at the university. All personal identifiers were removed from data and personal information linked to every interview was saved on a key-protected document.

Data collection decisions were made based on obtaining a diverse sampling and reaching data analysis saturation.

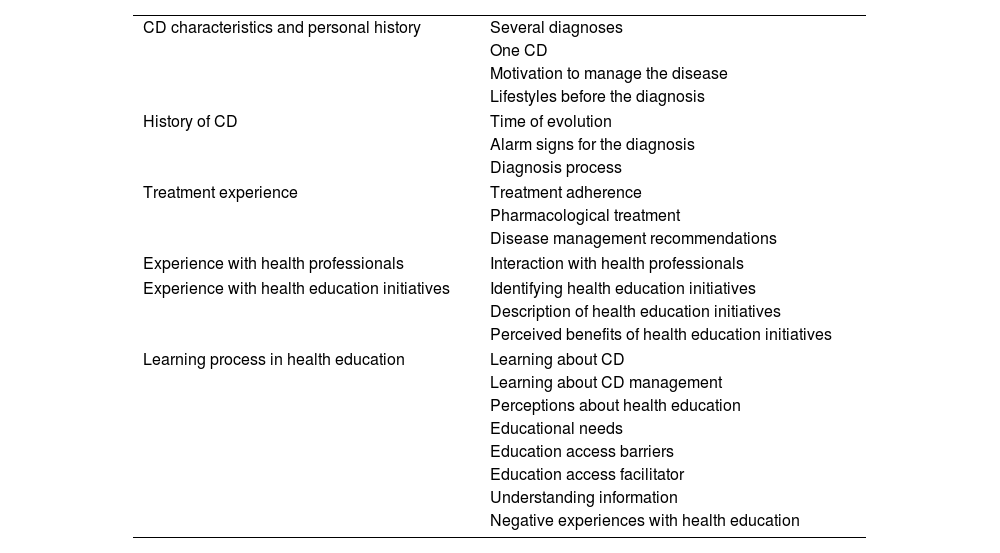

Data analysisThe codebook for data analysis was created using emergent codes10 from the first interview and the literature review on health education. The codebook included a total of 6 themes and 23 codes, and it was validated by an expert panel; it also included a description and an example of every code. After open coding, the research team conducted focused coding to analyze themes and major categories.10 To assure trustworthiness and avoid bias, every interview was coded by two researchers. An expert panel discussed the semantic networks created on ATLAS.ti to reach a final description of the phenomenon. Member checking was not conducted due to the COVID-19 quarantine measures. Table 2 includes the final themes and codes.

Themes and codes.

| CD characteristics and personal history | Several diagnoses |

| One CD | |

| Motivation to manage the disease | |

| Lifestyles before the diagnosis | |

| History of CD | Time of evolution |

| Alarm signs for the diagnosis | |

| Diagnosis process | |

| Treatment experience | Treatment adherence |

| Pharmacological treatment | |

| Disease management recommendations | |

| Experience with health professionals | Interaction with health professionals |

| Experience with health education initiatives | Identifying health education initiatives |

| Description of health education initiatives | |

| Perceived benefits of health education initiatives | |

| Learning process in health education | Learning about CD |

| Learning about CD management | |

| Perceptions about health education | |

| Educational needs | |

| Education access barriers | |

| Education access facilitator | |

| Understanding information | |

| Negative experiences with health education | |

The objective of this study was to describe the health education experiences of older adults with CD from their personal perspective. By understanding their unique individual experiences, the study also aimed at identifying older adults with CD's health education needs and expectations.

Three main categories describe how older adults with CD experience the health education process. First, older adults described the diagnosis process of the CD. Then, they described how they received recommendations for the comprehension and management of the disease. And, finally, they described their treatment adherence. Next, we will describe these categories and their subcategories in detail.

Chronic disease diagnosis processOlder adults become aware of the CD when they experience signs and symptoms leading them to a health checkup. This category has two subcategories: (a) symptoms and signs, and (b) lifestyles before the diagnosis. First, in most cases, an alarm or a set of alarm signs indicated that something was not going well with the older adult's health. This is the starting point of a series of medical appointments leading to diagnosis and treatment. For instance, Zulma mentioned her alarm signs, “[…] I had blurry vision, despondency, three sleepless nights, and then I decided to go to the doctor. I got blood tests and they discovered that my sugar was very high (around 200)” (ZFU07-07). Other participants also experienced despondency, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, thirst, tremblors, and other related symptoms. María (CAFU08-05) stated that she had a medical emergency related to a “stroke” and thus discovered she had high blood pressure. This case calls attention to the relevance of early diagnosis to prevent major health complications in older adults.

Other participants expressed that they did not experience a particular symptom or alarm sign. However, as part of their self-care process, they conducted routine exams that eventually resulted in the diagnosis of the CD. Gustavo stated, “My triglycerides were very high, between 600 and 650. So, the doctor measured my blood pressure, and it was very high. That's why the triglycerides were so high” (GMR1304). This narrative coincides with Sara's when she mentioned, “I had no symptoms. It is like right now. I just went to see the doctor and he ordered laboratory exams, and the doctor found all kinds of health complications” (SMU2807). Alarm signs could or could not appear, thus, the importance of routine health controls as an effective strategy for early diagnosis that minimizes the risk of further health complications.

Second, the lifestyles before the diagnosis impact the occurrence of CD in older adults. The life habits with major incidence reported by the participants were: tobacco and alcohol consumption and diet. Other lifestyles that had less influence, but were present, were lack of physical activity or sports practice. Regarding tobacco consumption, some participants recognized the relationship between smoking and CD. Mauricio expressed, “I have high blood pressure, […] and heart problems, because I was a heavy smoker. When I was a child, I smoked a lot until I was maybe 42 years old. Later I quit cigarettes” (GMU13-04). Likewise, Tomas said, “After the diabetes surgeries, I stopped smoking, I forgot all about it” (TMU02-08). Tobacco, alcohol consumption, and diet were the most reported lifestyles that affected the current health condition.

Regarding alcohol consumption, some participants related it to the appearance of the CD. Carlos expressed, “In the past, I drank a lot [smiles], heavy drinker, not a smoker but a heavy drinker” (CaFU08-06). Salomon also manifested that he had used to drink alcohol, but he quit the habit, “Right now, I don’t drink, but in the past, I did drink, and I drank a lot […] but I hit rock bottom, and I recovered and said no more drinking” (SOFR). Unlike Salomon and Carlos, other participants continued consuming alcohol despite the chronic disease. Tomas, for example, said “[…] I drink a couple of beers every other day […] maybe five pints” (TOMR02-08). The personal decision of continuing or not with alcohol consumption may depend on a variety of factors that determine if the person perceives the relationship between alcohol and CD or decides to continue drinking despite the health risks.

Regarding nutrition and physical activity, some participants related poor nutrition habits and lack of physical activity to chronic disease. Ana expressed, “I was a sportsperson before, I rode a bike a lot, and that made me feel well, but then I stopped exercising, and from there, I got diabetes, high blood sugar levels, because I didn’t exercise, I just ate” (NEMU22-04). In turn, Zulma questioned the nutrition habits she learned when growing up, a high-carbohydrates diet. She mentioned, “If dad or mom would have guided us on what to eat or not to eat, we would not be like this. And it is not only me, but there are a lot of people like me… In the past, we made cassava, arracacha, potato, corn on the cob, rice, and fried plantains in one meal” (ZFU07-07). This narrative makes visible the need to include health education throughout the cycle of life to foster healthy and balanced dietary and physical activity habits.

Recommendations for disease managementRegarding this category, older adults with CD reported that, once they were diagnosed with a CD, they received information about its management in two spaces: (1) in the health care facilities by doctors, nutritionists, or nurses; and (2) in informal spaces that emerge from their support networks, such as conversations with relatives, friends, community initiatives or public media, mostly radio and television. Next, we will provide details about these experiences.

First, at formal spaces in health care facilities, older adults experienced pharmacologic prescriptions, regular medical assessments with clinical exams to follow up on the disease, and dietarian recommendations. Regarding pharmacologic prescriptions, some participants remembered the medicine names, functions, and dosage. For example, Zulma explained, “First I take Losartan for blood pressure, Hydrochlorothiazide, for liquid retention, Omeprazole for the stomach, Acetaminophen if I am in pain, at noon, metformin, and Losartan again at night (ZFU07-07). Other participants could recall the function of each medicine, but not the actual name. Teresa said, “I take Losartan […] I forgot the other… the name. I know I take three medicines, but I don’t remember right now. One of 100 and another of 120 for blood pressure” (TFU02-08). Tomás also said, “[…] other medicines, but they are very difficult to remember, […] of course, they are all for blood pressure” (TMR02-08). In summary, most participants knew relevant information about their pharmacological prescriptions.

Other participants required the support of their caregivers to follow the pharmacological treatment. For example, the case of Ana and Fernando (wife and husband). Research team: What time do you take Losartan, the one for the blood pressure? Fernando: All of that is at 6 a.m. Ana knows better. Ana: Yes, he takes the medicines on time because I am the one who gives him the medication… Fernando: She is my control. Ana: I take my pills and then I give his pills to him. He only takes care of this (Rivaroxaban), which is why he has it there on the table. He takes it at 1p.m., which is lunchtime, so he takes care of that one. But I am on top of his medicine intake.

In this case, Ana was responsible for her husband's CD care and her care. Looking closer at Ana's discourse, she also knew that some medicine had more components than others. She stated, “This is one pill that contains the three for the high blood pressure: Valsartan, Hydrochlorothiazide and Amlodipine, so it's the three in one”. This case shows how Fernando's treatment adherence was possible thanks to Ana's support, who knew detailed information about the medicines. Even though older adults may or may not remember the names of the medications they were taking, they were aware of how the medical treatment affects their disease and established routines to take the prescribed medications.

In the data, we encounter a few participants who reported concern about polypharmacy in their CD treatment. Gloria manifested, “I don’t want to take so much medicine because medications also lead to health complications. I was told that taking too much omeprazole could be bad. Ever since I started taking it, I am not feeling well. Before I was taking Enalapril for blood pressure, and it was bad for me, so I told the doctor, and he prescribed Omeprazole, but someone told me that you get symptoms like the flu” (GMR13-04). Considering this case, it is important to educate older adults about polypharmacy in CD treatment.

Medical examinations are recurrent visits to health centers that are part of the self-care culture. In this regard, Cecilia expressed, “They are doing lab tests to check cholesterol and triglycerides, and several routinary exams to check the arthrosis, I also go to therapy every month” (CFR06-04). According to some participants, the essence of medical examinations and laboratory tests lies in ensuring the continuity of pharmacological treatment. Cristian reported, “They give you the prescription for two months and then, again, in the next appointment you get your medications, and in addition, they do blood tests, urine tests, cholesterol, and all of that. This happens every other month when you attend the medical checkup” (CoAM4). In contrast, Samuel mentioned that during the medical examinations, “they write everything on the computer, but they don’t say anything. Just take this medicine and that's all” (SMU28-07). Similarly, Marlene thought that during the medical examinations, “they don’t say anything. They prescribe the medicine and a bunch of prescriptions that I don’t understand” (CMU27-08). These two contrasting perspectives on medical examinations demonstrate the participants’ varied expectations regarding these settings, with a desire for improved communication regarding CD management.

Regarding nutrition, participants recognized the nutritionist orientations, which included high fruit and vegetable intake and reduction of unhealthy foods. Zoraida expressed, “The nutritionist said I cannot eat sweets, but ‘if sometimes you want to eat a cookie, you can have it because this is not going to happen every day’. I need to have a low sugar diet, eat fruits, not too sweet, no carbonated drinks, no desserts” (ZFR07-07). However, older adults perceived the adoption of new dietary habits as unnatural. For instance, eating more vegetables is associated with herbivorous animals: “You must stop eating chocolate, potatoes, carbohydrates, and now eat chard, cabbage, like feeding a bunny” (ZMU15-07). They also perceived diet as restrictive, with no option of choosing foods: “They say I can’t consume carbohydrates, fats, or even think about sugar or candies. Especially sugar, carbohydrates, fats, carbonated drinks, chocolate... they have restricted so many things from my diet” (GFU13-04). A nutritious diet is also associated with a lack of flavor: “A food without fat has no flavor, but is better, and salt, they took away the salt once and for all because of my high blood pressure” (CoFU19-05). These results highlight the necessity to explore alternative educational approaches in various settings, aiming to encourage a diverse and well-balanced diet that not only enhances the health of older adults but also motivates them to sustain healthy eating habits.

Most formal spaces where disease management occurs are professional appointments. Still, these spaces are complemented by other non-formal social spaces such as the family and mass media. Regarding the space of the family, Zoraida stated, “My cousins have had diabetes for 20 years, and they are alive, and I also knew people with diabetes who didn’t take proper care and died within 3 years. So, I think it has to do with auto control, diet… because if you are addicted to soda, ice-creams, pizza, junk food, then you are not getting better, but worse” (ZFR07-07).

Mass media also influences people's self-care decisions. Cecilia, for example, expressed, “I learned a lot from one TV channel called Conexión Vital with Dr. Rojas, where he explains about the human body and diseases, and he invites specialists, doctors, who explain to you this, it's like a school and you learn a lot through those TV programs” (CFR06-04). These spaces could be used by public institutions to produce content that promotes healthy living habits, not only for people with medical conditions but also for the general audience.

Treatment adherenceParticipants described treatment adherence based on (1) lessons learned for disease management, and (2) their motivation for self-care. Regarding the first subcategory, participants learned the relationship between auto control and disease management and their effects on health conditions. For instance, Zoraida stated, “If you get out of control, and eat desserts and things, then that is going to reflect on your lab tests. If you don’t take care, then obviously you will get worse” (ZFR07-07).

Prior to adhering to the treatment, older adults received information they comprehended but encountered challenges to transfer to their daily lives. In addition, some participants had a social and family network that facilitated treatment adherence, particularly when they share the same health conditions. Regarding the comprehension of health information, participants expressed, […] Maybe I did, because my mom and dad suffered from the same condition, and an uncle. They basically died of it, diabetes. Then you must assimilate and try… well, it's not that you do everything right [laughs], but I do try to take care of myself(CaFU08-06). […] Well, sometimes it's easy to understand, but sometimes your common sense does work(ToMU02-08). […] Well sometimes I do, I take all the control, but sometimes you don’t get to control everything well(SFR29-07).

Finally, motivation to self-care depends on two sources: one negative and one positive. The first one occurs when the older adult takes care of their health because of fear. For example, Tomas manifested, “I attended a diabetes workshop, where they told us we could lose a hand, a foot, or become blind, so many things. So, I follow the recommendations because I am afraid, for instance, my sister lost her legs” (TFR02-08). This narrative relates to Tania, who stated, “I take care of my health because of fear of getting sicker” (TAFU14-09). Similarly, Camilo expressed, “If you don’t control it, if you are not cautious, high bool pressure is a slow death” (CMU19-05).

In contrast, positive motivation occurred when older adults encountered affirmations to maintain positive aspects of life, a good life quality. For instance, Zulma stated, “I am aware that my life quality from now on depends on my effort, my disposition; because if I don’t take a good care, I will of course get worse” (ZFR07-07). In addition, Zoraida explained, “If you want to live, you must take a good care, because if I don’t care, I will see myself sicker, I won’t be able to jump or go out [laughs] so, you have to learn to live and live together” (ZFU07-07). Tomas added, “Because this is your health, it is for you; if you don’t take care, you will do it for you?” (ToFU02-08). Older adults’ positive motivation depends on the tools used by the health professional, the living environment, the social network, and other factors that will finally support them to adhere to the CD treatment.

DiscussionThis is the first study to explore qualitatively the health education experience of older adults with CD in Colombia. The study found that older adults’ experience started with recognizing alarm signs that were followed by a diagnosis provided by a health professional. Participants also acknowledged the role of their previous lifestyles in their current health condition. Consequently, participants received recommendations for disease management in formal and informal spaces. Health recommendations included pharmacological treatment, medical checkups, periodic laboratory tests, nutrition, and sometimes physical activity. Most older adults adhered to the treatment; this process was easier when they applied what they learned about disease management and received family support. Finally, motivation for self-care depended on negative and positive sources. The negative source is fear, and the positive is an awareness of the benefits of improving their quality of life.

One limitation of this study is the fact that transcribed interviews could not be returned to the participants due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, which started during the data collection phase.

Regarding the diagnosis process, this study found that when older adults received a late diagnosis, they usually did not notice alarm signs, and those who did not have a self-care culture experienced health complications. According to Ref.,11 a characteristic of CD is its slow and gradual development, which can make early diagnosis challenging because of the lack of signs or symptoms. That is why older adults need to follow a self-care process, including periodical health checkups. In this study, participants who conducted regular medical examinations received a timely diagnosis and avoided further health complications. Lee et al.12 found that early diagnosis presents benefits for disease prevention and early CD management. Additionally, when older adults receive quality health education, they adhere more frequently to the treatment and attend medical controls; the opposite occurs when older adults have limited access to information about CD.13,14

The results of this study regarding lifestyles associated with CD coincide with Net al.,15 who describe how CD is related to risk factors such as poor nutrition habits, smoking, alcohol abuse, and physical inactivity. Most participants did not recognize the relevance of including health education during the lifespan to promote healthy lifestyles. According to Bauer,16 to address this problem effectively, public health should include transversal strategies, including community conditions to support healthy habits and CD management for all. Bauer also propose to foster early detection and diagnosis to delay some disease complications.

In this study, some participants decided to quit alcohol consumption while others did not. The older adults’ perceptions about health and self-concept could be associated with the decision to continue with risky behaviors.17,18 These decisions also depend on diverse factors and the person's ability to associate their behaviors with their health condition.17,18 People who do not quit an unhealthy habit have a self-concept that does not accept other images of themselves, not even those given by the CD experience.17 Therefore, they avoid looking at themselves with a CD and resist the reconstruction of an altered self; they usually accept that their daily life has changed when their disease is at an advanced stage.17 Patients’ beliefs, preconceptions, and attitudes, which depend on their age, gender, lifestyles, occupation, educational level, and income, are reflected in a poor perception of health.

The findings of this study show that older adults perceive pharmacological prescriptions as the core of the physician's recommendations for CD treatment and management. Even when older adults do not remember the names of the medications, they establish their consumption as a habit to improve their health condition. However, they expressed limited knowledge about polypharmacy; only one person expressed concern about the number of medications she took and their secondary effects. According to Jia Hao et al.,19 polypharmacy increases the risk of adverse events such as confusion, falls, and functional impairment. As adults get older, they become more vulnerable to those secondary effects. That is why deprescription has been introduced, which refers to the effective and supervised modification, substitution, or withdrawal of medications in polypharmacy, and it is associated with better clinical outcomes.19

Regarding dietary recommendations, the findings of this study suggest the need for other forms of health education that promote a diverse and balanced diet to improve older adults’ health conditions while also motivating them to continue with healthy habits. Bernstein20 indicate that some nutritional education initiatives have the potential to improve overall well-being and promote health if they include periodic assessments and individual advice to improve their quality of life. Participants expressed that due to their health conditions, professionals recommended very restrictive diets. Therefore, this study aligns with research that suggests less restrictive and more flexible diets that adapt to the needs, resources, and health conditions through nutritional literacy.21

According to Alexandre and Peleteiro21 family participation is important to ensure that patients follow the recommendations. Additionally, family members can be motivated to change their behaviors if they face a high risk of developing a CD, which, in turn, supports the process for the older adult. Participants reported that it was easier to modify their lifestyles when they had a family member with CD due to changes in their perception of the disease risk.

Overall, the results of this study align with research about health literacy, a process that encompasses a wide range of people's abilities to learn, retain, and apply relevant health information provided by professionals.22 It is noteworthy the leading role of doctors and sporadically nutritionists in this study. It is necessary to involve other health professionals in the health education process with older adults. For example, physiotherapists could promote physical activity, nurses could foster self-care education, and psychologists could encourage a healthy self-perception, among others.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution since most participants in this study were women with basic education. Future studies could include a more diverse sample, including people from a broader socio-economic background. Future research should also explore possible gender, educational, and socio-economic differences in health education experiences.

ConclusionsThe older adults’ health education experiences with CD implied a learning process that depended on individual history, experiences, and external factors such as family support. Their experience primarily centered around communication with health professionals in formal and informal scenarios where they receive information about CD treatment. The health education process includes diagnosis procedures, recommendations for disease management, and verification of treatment adherence. This study is relevant because these results offer valuable information for the design of health education strategies to improve older adults’ empowerment in their healthcare process.

- •

Personalized Insights on Diagnosis and Management: The study provides detailed insights into how older adults recognize symptoms and manage their chronic diseases, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and personalized disease management strategies.

- •

Understanding of Treatment Adherence Factors: By identifying personal experiences and family support as key factors in treatment adherence, the study offers valuable information for developing interventions that enhance compliance with treatment plans.

- •

Role of Informal Support Networks: The research underscores the significance of informal networks, such as family discussions and media, in providing essential health education, suggesting opportunities to leverage these networks for better health outcomes.

- •

Adaptation and Motivation in Lifestyle Changes: The study shows how older adults adapt to and are motivated by lifestyle modifications, whether through fear of complications or the desire for improved quality of life, pointing to the need for health education that fosters positive lifestyle changes.

All participants voluntarily participated in the study and signed a consent form. The ethical committee of Universidad de La Sabana approved this study (IRB # 01115, June 2019).

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processWhile preparing this work, the authors used Chat GPT 4.0 to correct style and grammar mistakes. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FundingThis study was funded by the Universidad de La Sabana (2019) Convocatoria Interna Para La Financiación De Proyectos De Investigación, Creación, Desarrollo Tecnologico E Innovación. Project ID: ENF-19-2020.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could potentially create a conflict of interest.

The authors thank Sabana Centro Colombian region and participants for this study.