This study aimed to identify the key beliefs underlying the performance of walking under a clinically established pattern in women with fibromyalgia, distinguishing between those held by high vs. low intenders and high vs. low performers.

DesignLongitudinal prospective study with measures taken at two time points (T1 and T2) over a seven-week interval.

LocationAssociations of fibromyalgia of Alicante and Madrid.

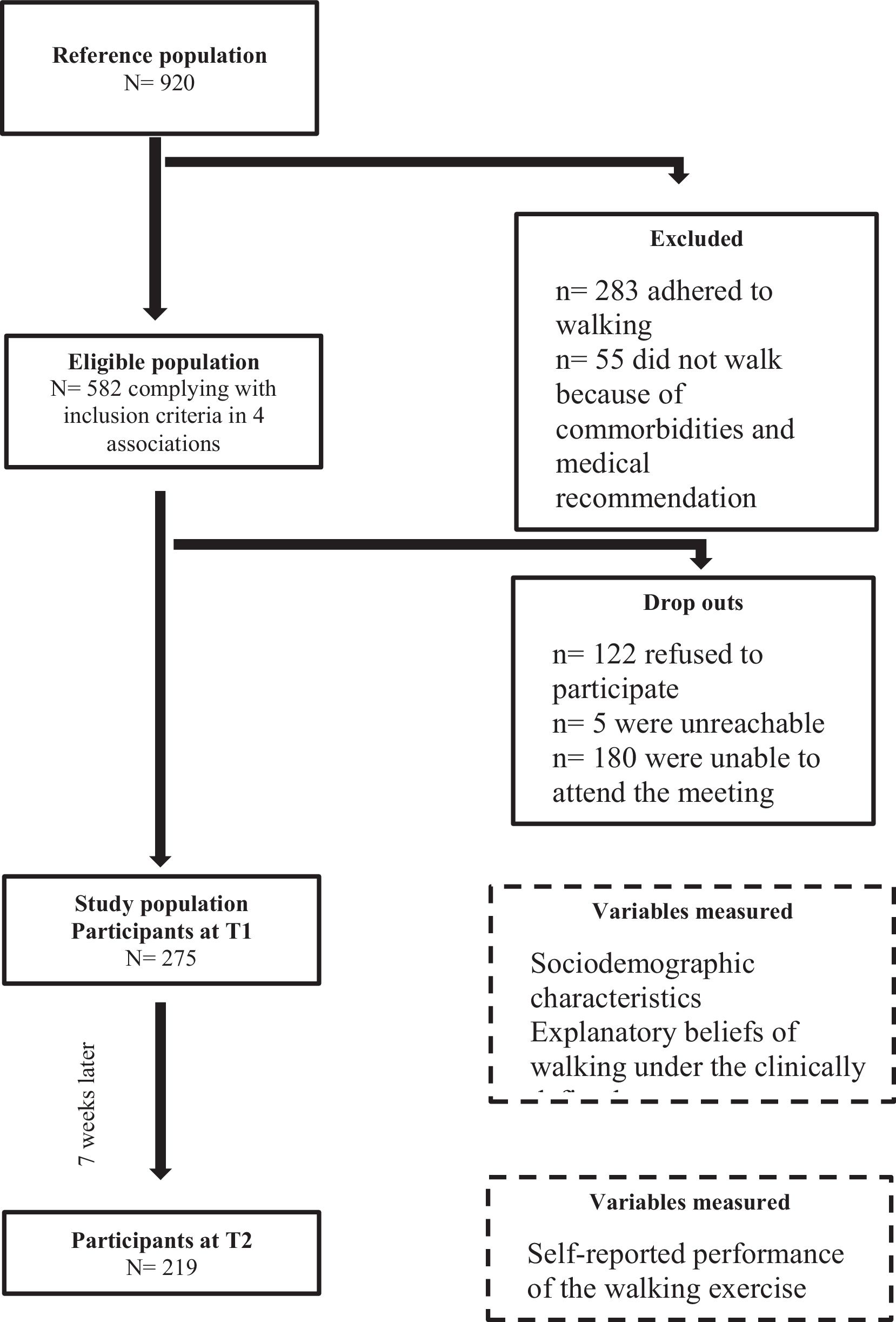

ParticipantsAt T1, 275 adult women with fibromyalgia diagnosis attending associations and that did not perform the walking exercise under the clinically established pattern. At T2, 219 women completing the follow-up.

Main measuresWith questionnaires, we assessed the strength of the behavioral, normative and control beliefs in relation to participants intention to engage in walking exercise (T1) and their actual performance (T2).

ResultsAmong high and low intenders of performing the walking exercise, significant differences were found regarding the median strength of eight behavioral beliefs (rank: U=4389.0, p≤.001; U=2356.5, p≤.05) and one facilitator control belief (U=4211.5, p≤.001). Significant differences among high and low performers were found regarding one inhibitor control belief (t=2.6, p≤.01).

ConclusionTo enhance motivation for walking exercise, eight specific behavioral beliefs should be targeted. However, for women to initiate and maintain adherence, reducing the strength of an inhibiting belief is required. This study provides the targets for primary health professionals to promote the walking exercise among women with fibromyalgia.

Identificar en mujeres con fibromialgia las creencias clave que explican la adhesión a la conducta de caminar, diferenciando entre las mujeres con alta y baja intención de caminar y con alto y bajo rendimiento.

DiseñoEstudio longitudinal prospectivo con mediciones realizadas en 2 momentos (T1 y T2) durante un intervalo de 7 semanas.

UbicaciónAsociaciones de fibromialgia de Alicante y Madrid.

ParticipantesEn T1, 275 mujeres adultas con diagnóstico de fibromialgia que asistían a asociaciones y que no realizaban el ejercicio de caminar. En T2, 219 completaron el seguimiento.

Medidas principalesMediante cuestionarios, evaluamos el peso de las creencias conductuales, normativas y de control en relación con la intención de realizar el ejercicio de caminar (T1) y su rendimiento real (T2).

ResultadosEntre quienes tenían alta y baja intención, se encontraron diferencias significativas en el peso medio de 8 creencias conductuales (rango: U=4389,0; p≤0,001; U=2356,5; p≤0,05) y una creencia de control (U=4211,5; p≤0,001). Entre las mujeres de alto y bajo rendimiento, solo se encontraron diferencias significativas en relación con una creencia de control (t=2,6; p≤0,01).

ConclusiónPara aumentar la motivación para caminar, se deben abordar 8 creencias conductuales específicas. Para que las mujeres inicien y mantengan la conducta, es necesario reducir la intensidad de una creencia. Este estudio proporciona las creencias diana que profesionales de atención primaria deben abordar para promover la adhesión a la conducta de caminar en las mujeres con fibromialgia.

Exercise is considered to produce beneficial effects on fibromyalgia symptomatology.1–3 Clinical guidelines recommend walking as a low-impact exercise with significant health benefits for women with fibromyalgia.4,5 Walking is an easy and accessible form of aerobic exercise, which can be performed in an unsupervised way once the patients are instructed about how to do it. However, among fibromyalgia patients, reported practice of walking is low6 and it has been also pointed out their high prevalence of sedentarism and low physical activity.7,8 Therefore, promoting the adherence to walking exercise becomes one of the challenges for clinicians.6,9 To facilitate initiating the habit, a specific walking pattern has been designed (brisk walking for 30min – split into two 15-min sessions with a short rest in between – twice a week for six weeks).10 However, strategies to promote such adherence are most effective when they target evidence-based determinants of behavior, making it easier to increase a person's intention to act.7

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) that has been applied to chronic pain studies.11,12 It is a widely validated model for predicting human behavior.13 However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have applied the entire model or its evolved version, the reasoned action approach (RAA),14 to predict adherence to a walking exercise routine specifically tailored for women with fibromyalgia. As part of a larger study, we applied the RAA to the specified walking exercise to identify key determinants of intention and adherence. Two clear predictors of intention were distinguished: attitudes towards themselves performing the walking exercise (a global assessment of the positive and negative consequences associated with carrying it out) and perceived control towards themselves performing the walking exercise (the extent to which individuals feel they can perform it). Additionally, perceived control was a direct predictor of the actual performance of the clinical walking pattern.15 Therefore, these predictors must be targeted to enhance women's motivation to perform the walking exercise and its performance. To such purpose, it is necessary to identify the explanatory beliefs that shape individual attitudes (behavioral beliefs) and perceptions of control (control beliefs).

Behavioral beliefs refer to the expected specific positive and negative consequences of performing the target behavior, whereas the control beliefs refer to the perceived specific facilitators and barriers. These beliefs represent the information patients have about performing the behavior and are shaped by other factors such as sex, gender, culture or personality traits.8

Although prior research15 has identified these beliefs, not all are equally influential in shaping the intention to exercise and exercising. Identifying these will allow health practitioners to focus on the beliefs that most effectively enhance motivation and behavior. According to the RAA, the strength of a behavioral belief depends on how likely the individual believes the expected consequence will occur (belief strength) and the degree to which they evaluate the consequence as positive or negative (outcome evaluation). Similarly, the impact of a control belief on women's perceived control over the walking pattern will depend on: how likely they believe that the facilitator or barriers will be present when carrying out the behavior (belief likelihood) and the extent to which the facilitator or barrier would affect their ability to engage in the behavior (belief power).

The present study aims to identify the beliefs that distinguish women with high vs. low intention to engage in the walking pattern, and high vs. low performers of the walking behavior. Identifying the latter is crucial because intention does not always lead to action,14 and addressing specific barriers may improve adherence.

Material and methodThis study is part of broader research (trial registration number: ISRCTN68584893). Further information on the predictors of the walking behavior, description of the sample and instruments can also be found in previous publications.15

Study designIt has a longitudinal prospective design. Data collection occurred at two time points:

T1 (Baseline): Participants completed a questionnaire assessing socio-demographic characteristics and all RAA constructs.

T2 (Follow-up, seven weeks later): Adherence to the walking program over the previous six weeks was assessed.

ParticipantsAt T1, the sample was composed of 275 women from four Spanish fibromyalgia patients’ associations in the Valencian and Madrid communities (ADEFA: n=22, 8%; AFEFE: n=94, 34.2%; AFIBROM: n=103, 37.5%; AFIBROTAR: n=56, 20.4%). The mean age was 52.4 (SD=9.2). Most of them were married or living with a partner (76%) and had primary education (47%) while working status was quite variable (33% were employed). At T2, 219 women remained in the study (74.4%).

No significant differences were found in sociodemographic and symptom perception variables between participants from different associations, nor between those who ultimately participated and those who did not. Additionally, no significant differences were observed between women who participated in both the T1 and T2 phases and those who participated only in the T1 phase. The mean time from initial fibromyalgia diagnosis was 10.3 years (SD=6.0). The mean pain intensity was 6.5 (SD=1.6; rank 0–10) and most women reported having a medical recommendation to walk to help manage their condition (n=214; 77.8%).15

ProcedureIn Fig. 1, detailed information on the procedure followed and for questionnaire administration can be found. Participants were eligible if they had a confirmed fibromyalgia diagnosis (a prerequisite for membership in the patient associations) and met the following criteria: (a) aged between 18 and 70 years old, (b) fulfilled the London-4 criteria to ensure diagnostic accuracy,16 (c) were not currently engaged in regular walking exercise or were walking but did not meet the minimum requirements of the specified walking pattern. Participants with comorbid conditions were eligible if they had received a medical recommendation to walk.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Miguel Hernández University (reference n°: DPS-MPM-001-11) and all participants signed an informed consent form. The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration.

Variables and instrumentsSociodemographic and fibromyalgia variables (T1): sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (age, educational level, marriage status and working situation) were collected through an ad-hoc questionnaire. The questionnaire also assessed duration of illness, pain intensity, and whether participants had received medical advice to walk (yes/no). The response rate for this section was 99% (273/275).

Reasoned action approach variablesThe measurement scales used in this study were based on established RAA guidelines and had been previously validated.17 These scales demonstrated good psychometric properties. In summary, the scales included seven items for measuring attitude, nine items for perceived control, five items for the intention to perform the walking pattern, and two items for self-reported adherence to the complete recommended walking pattern. All items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale. Higher scores meant more positive attitudes, higher perception of control, stronger intention and higher reported adherence to the walking pattern.

Behavioral beliefsFourteen beliefs about the expected outcomes of adhering to the walking pattern, as identified in a previous study,17 were assessed. These beliefs were evaluated in terms of ‘belief strength’ (the likelihood that the consequence will occur if the participant engages in the walking pattern, rated on a Likert scale from 1=very unlikely to 7=very likely) and ‘outcome evaluation’ (the perceived value of each consequence, rated on a Likert scale from 1=very good to 7=very bad) (response rate: 256/275, 93%). The score for each belief is the result of the multiplication of the two components [0–49].

Control beliefsSeven control beliefs identified in the aforementioned study17 were assessed in terms of ‘belief likelihood’ (the perceived probability that facilitators or inhibitors will be present during the six-week walking program) rated on a Likert scale from 1=very unlikely to 7=very likely) and the ‘perceived power’ for each facilitator an inhibitor (the perceived degree to which each factor facilitates or inhibits the walking behavior, rated on a Likert scale from 1=not at all powerful to 7=very powerful) (response rate: 262/275, 95%). The score for each belief is the result of the multiplication of the two components [0–49].

Data analysisAnalyses were conducted with the SPSS 23 Statistics Package (Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed for all variables. Normality was measured using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test or the Shapiro–Wilk test, in the case of smaller subgroups. Participants were divided into low and high intenders and low and high performers based on their mean scores for intention or behavior. Scores below four points classified participants as low intenders or low performers, while scores above five points classified them as high intenders or high performers. To compare differences between groups in terms of beliefs and intention, as well as beliefs and walking behavior, Student's t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted depending on the distribution of the variables. Due to the exploratory character of this study and to balance type I and II errors, p value was established at p≤0.01.

ResultsBeliefs that distinguish high and low intenders from performing the walking patternSignificant differences were found between low and high intenders in eight behavioral beliefs, based on the belief strength×outcome evaluation score. The four strongest beliefs among high intenders were: “My circulation will improve” (M=44.6; SD=7.7), “It will be good to distract me and to clear my mind” (M=43.7; SD=8.5), “It will strengthen my muscles and will improve my joints” (M=41.2; SD=11.5) and “I will feel more positive, happier with myself and feel more accomplished” (M=41; SD=10) (Table 1).

Significant differences in beliefs between groups with high and low intention of performing the walking pattern.

| Behavioral beliefsa | Intention low/high | Mean (SD) | U | p | Mean difference | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will feel better; my health will improve | Low | 27.2 (15.7) | 4157.5 | 0.004 | −8.6 | [−13.9 to −3.3] |

| High | 35.8 (13.1) | |||||

| My mood will be better, I will feel in a better mood, more relaxed | Low | 26.5 (16.4) | 4402.5 | 0.000 | −11.3 | [−17.8 to −4.8] |

| High | 37.8 (11.9) | |||||

| I will be moving about, I will feel more active and agile | Low | 28.6 (18.0) | 4166.5 | 0.003 | −10.9 | [−18.0 to −3.8] |

| High | 39.5 (11.7) | |||||

| I will feel more positive, happier with myself and feel more accomplished | Low | 30.3 (16.1) | 4389.0 | 0.000 | −10.7 | [−17.1 to −4.4] |

| High | 41.0 (10.0) | |||||

| My blood circulation will improve | Low | 32.6 (19.0) | 4230.0 | 0.001 | −12.0 | [−19.4 to −4.6] |

| High | 44.6 (7.7) | |||||

| I will lose weight | Low | 24.7 (17.6) | 3956.0 | 0.009 | −9.0 | [−15.1 to −2.9] |

| High | 33.7 (14.9) | |||||

| It will be good to distract me and to clear my mind | Low | 31.2 (18.2) | 4281.0 | 0.000 | −12.4 | [−19.6 to −5.3] |

| High | 43.7 (8.5) | |||||

| It will strengthen my muscles and will improve my joints | Low | 31.2 (16.8) | 4250.5 | 0.001 | −10.0 | [−16.6 to −3.3] |

| High | 41.2 (11.5) | |||||

| I will feel more contracted and with more stiffness | Low | 19.1 (13.6) | 3255.5 | 0.79 | −0.7 | [−6.3 to 4.8] |

| High | 19.8 (13.5) | |||||

| It will reduce, alleviate my pain | Low | 28.7 (16.4) | 3293.0 | 0.63 | −1.9 | [−8.5 to 4.6] |

| High | 30.7 (13.4) | |||||

| I will feel more pain in my feet, knees, hips … all over my body | Low | 27.7 (16.7) | 3310.5 | 0.63 | −1.8 | [−8.5 to 4.9] |

| High | 29.5 (14.7) | |||||

| I will be more tired, wearier | Low | 25.9 (14.3) | 3661.5 | 0.14 | −4.4 | [−10.3 to 1.4] |

| High | 30.3 (14.2) | |||||

| I will be more in contact with people | Low | 29.4 (18.9) | 3640.0 | 0.15 | −5.8 | [−13.4 to 1.7] |

| High | 35.3 (14.2) | |||||

| I will feel bad if I have this obligation and I don’t carry it out | Low | 20.8 (15.1) | 3715.5 | 0.12 | −4.7 | [−10.9 to 1.5] |

| High | 25.5 (15.7) | |||||

About the control beliefs, significant differences were found only in the facilitator belief “Have someone to motivate me”. The mean of the product belief likelihood-control power was higher among the high intenders (M=32.3; SD=15.2) (Table 2).

Significant differences in beliefs between high and low performers of the walking pattern.

| Control beliefsa | Low/high performers | M (SD) | t | p | Mean difference | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiredness | Low | 32.1 (13.2) | 2.0 | 0.05 | 4.1 | [0.2 to 8.2] |

| High | 27.9 (13.1) | |||||

| Being in pain | Low | 35.8 (13.0) | 2.6 | 0.01 | 5.3 | [1.2 to 9.4] |

| High | 30.5 (30.5) | |||||

| My mood (sad, stress, worries) | Low | 25.3 (14.7) | 2.0 | 0.05 | 4.3 | [0.0 to 8.6] |

| High | 21.0 (13.3) | |||||

| Bad weather (heat or cold, rain) | Low | 25.7 (13.4) | −0.3 | 0.81 | −0.5 | [−4.7 to 3.6] |

| High | 26.3 (13.2) | |||||

| Having someone for company | Low | 25.5 (16.4) | 0.8 | 0.94 | .20 | [−5.0 to 5.4] |

| High | 25.3 (17.0) | |||||

| Feeling bad, having a bad day | Low | 32.6 (14.3) | 1.5 | 0.13 | 3.5 | [−1.0 to 8.0] |

| High | 29.1 (14.5) | |||||

| Have someone to motivate me | Low | 34.9 (13.3) | 1.5 | 0.14 | 3.5 | [−1.2 to 8.2] |

| High | 31.4 (15.7) | |||||

No significant differences were found in behavioral beliefs between high performers and low performers of the walking exercise pattern. Significant differences were only found related to one inhibitory control belief (product belief likelihood-control power of ‘being in pain’) which was higher among low performers (M=35.8; SD=13.0). In Table 2, the results can be seen on the remaining control beliefs.

DiscussionInterventions to increase levels of physical activity among patients must be comprehensive, addressing both capability and motivation to engage in exercise. In this study, findings provide health practitioners with targeted beliefs to address to promote walking exercise more efficiently.

The behavioral beliefs identified in our study to increase motivation for walking include both instrumental health-related outcomes (e.g., improved circulation, stronger muscles and joints, increased physical activity) and affective benefits (e.g., improved mood, a sense of accomplishment, and personal fulfillment). This highlights the significant role of affective benefits for women with fibromyalgia, given the strong link between fibromyalgia and emotional distress.16 Additionally, it emphasizes the need to provide information about general health benefits beyond pain relief. In a recent systematic review, a lack of knowledge and understanding of these benefits has been identified as a barrier to physical activity adherence.18

It is especially striking that ‘alleviating pain’ is not among the key instrumental beliefs that differentiate high intenders from low intenders. This could indicate that both groups perceive this benefit in similar ways, assume that their pain is a chronic issue, or because their previous experience walking exercise (outside of a clinical context) proved contrary. The latter explanation seems most likely, as both high and low intenders similarly perceive walking as potentially worsening pain, leading to increased stiffness, muscle tightness, or fatigue. For this reason, to avoid exacerbating symptoms9 it is crucial to prescribe walking following the clinically recommended pattern.6

Surprisingly, only one facilitating control belief stood out in enhancing intention: ‘having someone to motivate them’. Previous studies have shown that social support is a facilitator of performing physical activity among older adults.19 Family members may sometimes act overprotectively, become over-involved or employ avoidance-coping strategies.20 This may result in the family discouraging walking to protect the patient from pain or fatigue or not recommending it at all if they do not fully understand fibromyalgia as a health issue. Therefore, it may be interesting to talk to family members for them to properly understand the health issues and help promote walking exercise. Additionally, healthcare professionals need to play an active role, by prescribing exercise, motivating patients and helping them find supportive social environments.21

Once motivation has been boosted, professionals must focus on one key inhibitory control belief that hinders the initiation of the walking pattern: ‘being in pain’. Addressing this requires providing education on how symptoms and sedentary behaviors contribute to increased pain during activity and how these factors impair physical function and exacerbate fatigue.4 However, only providing information may not be sufficient. It is just as important to increase personal resources to help them manage inhibitors. To this end, strategies focused on behavioral self-regulation (such as implementation intention) – could be helpful since they have shown to be efficient in physical activity.22

LimitationsFirst, the findings rely on the use of self-reports to measure the beliefs and construct of the RAA and the adherence to the walking pattern. Nevertheless, previous studies have not found differences between self-reported measures of walking and objective measures.23 Secondly, a considerable number of eligible candidates did not participate, most for not being able to attend the meeting. Among those who refused participating, the reasons are unknown, although it is important to note that no differences were found in the sociodemographic and clinical variables between women who participated in the study and those who did not. Thirdly, caution is needed when generalizing these findings to other fibromyalgia populations. Fourthly, interventions that are tailored to the person's situation have been identified as a facilitator of adherence to physical activity in general.18 However, we should also bear in mind that the beliefs identified in our study are modal beliefs – those most shared by women with fibromyalgia – and thus are likely to be held by this group.

Practical implicationsConsidering the time constraints in healthcare settings,21 this study provides keys to efficiently promote adherence to physical exercise in women with fibromyalgia which remains a challenge. To increase motivation for walking exercise, women need accurate information about both the emotional and practical benefits of following the specific clinical walking pattern, highlighting its benefits for symptom management, and emphasizing its potential to achieve the long-awaited goal of pain relief.24 Family members should be included in the informative session to act as facilitators of walking exercise and health professionals should also play a role as motivators. Once motivated, self-regulation strategies may be useful for patients to maintain their walking behavior. Future studies should focus on designing efficient interventions addressing such beliefs.

- -

Walking exercise is crucial for managing pain in fibromyalgia patients, yet adherence remains low.

- -

By using an evidence-based framework, this study identifies the specific beliefs that healthcare professionals should target to increase motivation and adherence to walking exercise.

- -

Practical recommendations are provided, including specific information to be conveyed to enhance walking exercise adherence in clinical settings.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Miguel Hernández University (reference no.: DPS-MPM-001-11) and all participants signed an informed consent form. The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThis work was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [MINECO; PSI2011-25132]. This institution did not participate in the project.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We would like to thank the associations and women with fibromyalgia that made this project possible.