To determine if there are significant differences between Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) patients who live in urban and rural areas and to analyze the correlation between the impact of the disease, Central Sensitization (CS) and pain sensitivity, including its possible correlation with the rest of the clinical variables in patients with FMS.

DesignObservational cross-sectional correlational study.

LocationRural and urban areas in Jaén (Spain).

ParticipantsPatients with FMS.

Main measurementsThe outcome variables measured were the impact of FMS on daily life, Central sensitization CS, pain sensitivity, self-esteem, pain, Quality of Life (QoL), anxiety and depression, and sleep quality. Also, sociodemographic and clinical data, were collected.

ResultsNo differences were found between the groups for sociodemographic and clinical variables, except for educational level (p=0.01). Low-to-moderate significant association between the impact of FMS, CS and pain sensitivity were found (p<0.01). Low-to-strong significant associations were observed between the impact of FMS, CS and pain sensitivity with pain, QoL, anxiety and depression and sleep quality (p<0.01). Furthermore, a very strong association was found between impact of FMS and QoL (p<0.01).

ConclusionsNo differences were found between FMS rural/urban groups for sociodemographic and clinical variables, except for educational level. There was a significant association between the impact of FMS, CS and pain sensitivity in patients with FMS, regardless of their area of residence. Besides, a very strong association was found between Impact of FMS and QoL.

Determinar si existen diferencias significativas entre pacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia que viven en zonas urbanas y rurales, y analizar la correlación entre el impacto de la enfermedad, la sensibilización central y la sensibilidad al dolor, incluyendo su posible correlación con el resto de variables clínicas en pacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia.

DiseñoEstudio observacional transversal correlacional.

LocalizaciónZonas rurales y urbanas de Jaén (España).

ParticipantesPacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia.

Medidas principalesLas variables de resultado fueron el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia en la vida diaria, la sensibilización central, la sensibilidad al dolor, la autoestima, el dolor, la calidad de vida, la ansiedad y depresión y la calidad del sueño. Además, se recogieron datos sociodemográficos y clínicos.

ResultadosNo se encontraron diferencias entre los grupos en las variables sociodemográficas y clínicas, excepto en el nivel educativo (p=0,01). Se encontró una asociación significativa de baja a moderada entre el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia, la sensibilización central y la sensibilidad al dolor (p <0,01). Se observaron asociaciones significativas de bajas a fuertes entre el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia, la sensibilización central y la sensibilidad al dolor con el dolor, la calidad de vida, la ansiedad y la depresión y la calidad del sueño (p <0,01). Además, se encontró una asociación muy fuerte entre el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia y la calidad de vida (p <0,01).

ConclusionesNo se encontraron diferencias entre los grupos rurales/urbanos para las variables sociodemográficas y clínicas, excepto para el nivel educativo. Hubo una asociación significativa entre el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia, la sensibilización central y la sensibilidad al dolor en pacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia, independientemente de su área de residencia. Además, se encontró una asociación muy fuerte entre el impacto del síndrome de fibromialgia y la calidad de vida.

Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is defined as a chronic disorder of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of generalized pain, and associated with numerous symptoms such as fatigue, anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality.1 The overall prevalence of FMS worldwide is 2.7%2 (2.45% in Spain).3 Regarding gender, the female prevalence was 4.2% and the male prevalence was 0.2% in Spain in 2022, with a female-to-male ratio of 21:1.4 Besides, some studies indicate that FMS is more common in women aged 50 and over with low educational and socioeconomic levels and who live in a rural area.2

Those affected by FMS mainly suffer from hyperalgesia and allodynia, which are examples of disturbed pain processing in the central nervous system. They are core features of central sensitization (CS), which is defined as an increased responsiveness of the central nervous system to a variety of stimuli like pressure, temperature, light and medication.5 As well as these symptoms, it is common for FMS patients to experience gastrointestinal and somatosensory alterations such as paresthesia. All of this can lead to both physical and psychosocial disability, greatly reducing the quality of life (QoL) of these patients.6 Although the cause is still unknown, advances in research have shown that FMS could be due to alterations in pain processing within the nervous system. Therefore, diagnosing FMS is complex, due to the absence of clinical or analytical markers that confirm this disorder.7

The patient's geographical setting is an important factor to consider, as there can be differences between rural and urban areas.8 The term ‘rural area’ is often poorly defined. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines rural areas as those with population densities below 150inhabitants per square kilometer.9 Traditionally, rural areas were considered to have different features to urban areas, such as low population density, inhabitants who mostly work in agriculture, strong community ties among the local population, and the preservation of typical features of a traditional, rural culture.10 In Spain, it is “the geographical area comprising municipalities or small local authorities defined by the relevant authorities as having a population of less than 30,000inhabitants and a population density of less than 100inhabitants per square kilometre”.11

Some existing literature has found a link between FMS patients’ area of residence and the impact of the disorder. However, these findings have been inconsistent.3,4,12 The EPISER 2000 prevalence study of rheumatic diseases in the adult population in Spain showed that the most important determinants for the presence of FMS in the Spanish population were being a woman, having other chronic diseases and living in a rural area.13 However, the EPISER 2016 study concluded that no associations were found between suffering from FMS and living in a rural area.14 A study published in 2021 showed that patients in rural areas had higher levels of pain acceptance and lower levels of physical and mental fatigue compared to those from the urban area.12

Therefore, the main objective of this research was to determine if there are significant differences between Fibromyalgia Syndrome patients who live in urban and rural areas in terms of the impact of the disorder, CS, pain sensitivity, self-esteem, pain, QoL, anxiety and depression, and sleep quality. The secondary objective was to analyze the correlation between the impact of the disease, CS and pain sensitivity as well as its possible correlation with the rest of the clinical variables in patients with FMS.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsA descriptive cross-sectional correlational study was conducted between January 2023 and April 2024 with a sample of 113 patients diagnosed with FMS. The rural patient cohort was drawn from two mountainous regions of the province of Jaén. These regions have 35 population centers (with at least 50 inhabitants per center) with a total of approximately 39.000 inhabitants, of which 32.370 (83%) are adults. Applying the 2.47% prevalence in Spain of FMS according to Font Gayà et al. (2020),3 we estimate 799 potential patients with FMS in these regions. Considering the wide geographic dispersion, we consider that a sample equivalent to 5% of this population (i.e., 40 participants) provides an adequate basis for statistical analysis. Rural participants were recruited from a database of a physiotherapy clinic located in a rural area (Peal de Becerro, Jaén, Spain) with a population density of 36.30inhabitants per km2,15 and from the Fibromyalgia Association of the Jaén (AFIXA) which has branches in rural areas across Jaén (Eastern Andalusia, Spain). Urban participants were recruited from AFIXA located in Jaén capital whose population density is 263.41inhabitants per km2.15 The participants were classified according to the habitual place of residence (rural area/urban area), as in previous studies,12 based on the most current publication of a Spanish Ministry.16 The participants were contacted via telephone, messages, and social networks to participate in an interview. Those who could not attend an in-person interview were sent a link to complete the questionnaires through the ‘Google Forms’ tool.

Ultimately, 80 participants with FMS were included in this study. A flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jaen (Code ENE.22/1.PRY) and was carried out in strict compliance with the World Health Organization's ethical standards and procedures for research with human beings (Declaration of Helsinki). All subjects received information about the study and signed written informed consent to acknowledge the voluntary nature of their participation.

Inclusion criteria were: to have an FMS medical diagnosis (rheumatologist) that met the 2016 diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR),17 to be between 18 and 65 years of age, to reside in a rural or urban area, to be able to read in Spanish, to have understood and accepted the informed consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were: to be diagnosed with any mental illness that would prevent follow-up of the intervention, to be diagnosed with inflammatory rheumatic disease, to have had a surgical intervention either in the previous six months or scheduled during the data collection, or to have changed pharmacological treatment during the study or in the three months prior.

Outcomes variablesDemographic, anthropometric, and clinical data, such as residence area, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), years with FMS diagnosis, academic education, employment status, smoking habits, marital status and physical exercise, were collected by well-trained interviewers.

The outcome variables measured were the impact of FMS on daily life, CS, pain sensitivity, self-esteem, pain, QoL, anxiety and depression, and sleep quality.

- -

To assess the impact of FMS on daily life, the Spanish version of the revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) was used. It assesses the function, impact and symptoms related to FMS and scores from 0 to 100, with 100 being the maximum impact of FMS on QoL. The Spanish FIQR had high internal consistency (Cronbach's α 0.91–0.95). The test–retest reliability was good for the FIQR total score and its function and symptoms domains (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC>0.70), but modest for the overall impact domain (ICC=0.51).18

- -

Central sensitization (CS) was measured with the Spanish version of the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI). It is a self-report outcome measure designed to identify patients who have symptoms that may be related to CS or CS syndromes such as FMS. It consists of 25 questions related to common CS symptoms, with total scores ranging from 0 to 100. The Spanish version of the CSI demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.872) and a one-dimensional factor structure.19

- -

Pain sensitivity was measured with the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ), which consists of 17 items in a 11-point Likert format. This questionnaire assesses pain sensitivity based on pain intensity ratings (range: 0–10) of painful situations that occur in daily life. The PSQ can be calculated as a total score (PSQ-total), a PSQ moderate score (the sum of items 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 16 and 17, which represent situations of moderate pain), or a PSQ minor score (the sum of items 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12 and 14, which represent situations of mild pain). Items 5, 9 and 13 are not taken into consideration because they represent non-painful situations. The Spanish validation results showed an excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α>0.9) and a substantial reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient>0.8).20

- -

The Spanish version of the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES) was used to analyze the self-esteem of patients with fibromyalgia. It is a self-report measure designed to evaluate the concept of overall self-esteem and includes 10 items scored on a 4-point scale that are added together to create a single self-esteem index. The higher the score, the higher the level of self-esteem. The Spanish version presents high internal consistency (Cronbach's α>0.87).21

- -

Pain was evaluated with the Spanish version of the Chronic Pain Grading Scale (CPGS), which consists of 8 items in an 11-point Likert format with a total range of 0–70. The final score is the sum of items 2–8. The higher the score, the greater the pain intensity. The Spanish version has high internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.87) similar to that presented by versions in other languages, and ICC=0.81.22

- -

To evaluate quality of life (QoL), the Spanish version of the Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) was used. This questionnaire consists of 16 items that include various aspects of life, such as physical and material well-being; relationships with other people; social, community and civic activities; personal development and fulfillment; leisure; and independence. Each item was scored from 0 to 7 and the total score ranged from 16 to 112. The higher the total score, the higher the QoL. The Spanish version shows high internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.887). The value of ICC for the QOLS total is 0.765 (95% CI: 0.649–0.843, p<0.001).23

- -

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Spanish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). This scale comprises two subscales: the HAD Anxiety subscale (HADA) and the HAD Depression subscale (HADD). This questionnaire consists of 14 items, rated from 0 (no distress) to 3 (maximum distress). The cut-off score for the presence of anxiety and depression symptoms must be equal to or greater than 8. The internal consistency of the scales of the Spanish version is Cronbach's α=0.80 for the HADA and Cronbach's α=0.85 for the HADD.24

- -

Sleep quality was measured using the Spanish version of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS-SS), which includes 12 items divided into six different subscales: Sleep disorders (items 1,2,7,8); Daytime sleepiness (items 6,9,11); Sleep adequacy (items 4.12); Snoring (item 10); “I wake up with difficulty breathing or a headache” (item 5) and amount of sleep/optimal sleep (item 2). Ten of the 12 MOS-SS items are scored on a six-point categorical scale ranging from “all the time” to “none of the time”. The question about the time needed to fall asleep uses a five-point scale ranging from “0 to 15minutes” to “more than 60minutes”. Participants report “sleep quantity” as the average number of hours they sleep per night. All items except “amount of sleep” are recalibrated on a scale from 0 to 100 representing the percentage of a particular sleep item, and item 2 was recorded as the average number of hours slept per night (0–24h). The scale also includes two indices: the ‘Sleep Problems I index’ which summarizes sleep problems using an abbreviated six-item index (items 4,5,7,8,9,12); and the ‘Sleep Problems Index II’, which uses 9 of the 12 scale items to calculate an overall summary of sleep problems (all items except 2,10,11). Higher ratings for items indicate worse sleep problems. The Spanish version of the MOS-SS showed excellent and substantial reliability in Sleep Problems Index I and Sleep Problems Index II, headache), respectively, and good internal consistency with optimal Cronbach's alpha values in all domains and indexes (0.70–0.90).25

Data was analyzed using the SPSS 21.00 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The database is open access.26 The significance level was set at 0.05 for all tests and the confidence interval at 95%. The normality of the data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A descriptive analysis was performed using means and standard deviations for quantitative variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. To check the homogeneity of the groups, the Student t test was used to analyze the distribution of the quantitative variables and the Chi square test was used for categorical variables.

Pearson or Spearman correlations (depending on the normality of data) were run to assess the association between FIQ, CSI and PSQ and to analyze their correlation with other different continuous variables. The correlation coefficient was considered ‘strong’ if it was>0.50, ‘moderate’ if it was between 0.30 and 0.50 and weak<0.30.

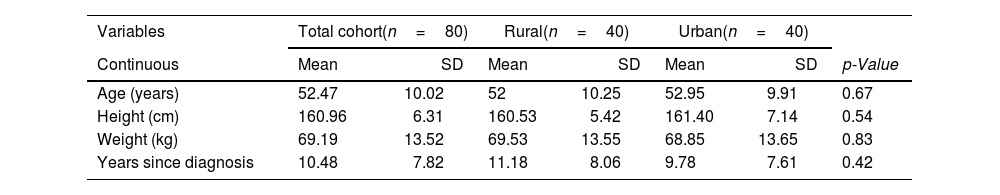

ResultsA total of 80 participants met the inclusion criteria and completed all of the questionnaires included in the study. There were 40 participants in each of the two study groups. The sociodemographic and most relevant clinical factors of the study sample are presented in Table 1. The sample had a mean age of 52.47 (10.02) years; 52 (10.25) years in rural areas and 52.95 (9.91) years in urban areas. The participants had a mean BMI of 26.7 (5.15). Both the participants from rural areas and urban areas were overweight with a mean BMI of 26.99 (5.18) and 26.47 (5.17) respectively. Regarding weekly physical activity levels, around 30% of the participants did exercise two to three times per week. In relation to education level, significant differences were found (p<0.01); 35% (n=14) of the participants from urban areas had university studies, compared to only 12.5% (n=5) from rural areas. Furthermore, 7.5% (n=3) of the rural sample had no basic education. As for employment status, 52.5% (n=42) of the sample was in full-time employment. In our study, differences close to the level of significance (p=0.08) were found in relation to being a smoker, which was higher among urban participants. No significant differences were found between the groups for the rest of the sociodemographic variables.

Descriptive characteristics of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS). Total cohort and the two populations independently.

| Variables | Total cohort(n=80) | Rural(n=40) | Urban(n=40) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-Value |

| Age (years) | 52.47 | 10.02 | 52 | 10.25 | 52.95 | 9.91 | 0.67 |

| Height (cm) | 160.96 | 6.31 | 160.53 | 5.42 | 161.40 | 7.14 | 0.54 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.19 | 13.52 | 69.53 | 13.55 | 68.85 | 13.65 | 0.83 |

| Years since diagnosis | 10.48 | 7.82 | 11.18 | 8.06 | 9.78 | 7.61 | 0.42 |

| Categorical | F | % | F | % | F | % | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level | |||||||

| None | 3 | 3.8 | 3 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Primary | 29 | 36.3 | 19 | 47.5 | 10 | 25 | |

| Secondary | 29 | 36.3 | 13 | 32.5 | 16 | 40 | |

| University | 19 | 23.8 | 5 | 12.5 | 14 | 35 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Professional active | 42 | 52.5 | 22 | 55 | 20 | 50 | 0.85 |

| Unemployment | 18 | 22.5 | 8 | 20 | 10 | 25 | |

| Retired | 20 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 25 | |

| Smoker | |||||||

| No | 40 | 50 | 25 | 62.5 | 15 | 37.5 | 0.08 |

| Former smoker | 18 | 22.5 | 7 | 17.5 | 11 | 27.5 | |

| Yes | 22 | 27.5 | 8 | 20 | 14 | 35 | |

| Civil status | |||||||

| Single | 8 | 10 | 3 | 7.5 | 5 | 12.5 | 0.58 |

| Married | 58 | 72.5 | 30 | 75 | 28 | 70 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 12.5 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 15 | |

| Widower | 4 | 5 | 3 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Exercise | |||||||

| No or once/month | 12 | 15 | 5 | 12.5 | 7 | 17.5 | 0.53 |

| Once or twice/week | 30 | 37.5 | 14 | 35 | 16 | 40 | |

| Three times/week | 23 | 28.7 | 11 | 27.5 | 12 | 30 | |

| Daily | 15 | 18.8 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 12.5 | |

Data are given as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The Student t test was used to analyze the distribution of the quantitative variables and the Chi square test was used for categorical variables.

Regarding the outcome variables, there was a moderate to severe impact of fibromyalgia on daily life, with a mean total score of 67.61 (17.76); 66.57 (19.25) in rural areas and 68.65 (16.32) in urban areas. In terms of CS, the sample obtained a mean total score of 58.74 (17.5). The participants had high pain sensitivity, reporting a mean of 7.46 (1.51). No statistically significant differences were found between groups in clinical variables, as shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows the results of the correlations between CSI, PSQ and FIQ scores and some clinical variables.

Between-group differences in clinical variables.

| Variables | Total cohort(n=80) | Rural(n=40) | Urban(n=40) | Mean differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-Value | |

| FIQ (0–100) | 67.61 | 17.76 | 66.57 | 19.25 | 68.65 | 16.32 | 0.60 |

| CSI (0–100) | 58.74 | 17.5 | 57.03 | 18.13 | 60.45 | 16.92 | 0.39 |

| PSQ (0–10) | |||||||

| Total | 7.46 | 1.51 | 7.56 | 1.66 | 7.36 | 1.35 | 0.54 |

| Moderate | 7.96 | 1.46 | 8 | 1.59 | 7.93 | 1.32 | 0.84 |

| Minor | 6.96 | 1.72 | 7.13 | 1.86 | 6.78 | 1.56 | 0.37 |

| RSES (10–40) | 27.43 | 3.51 | 28.1 | 3.8 | 26.75 | 3.08 | 0.08 |

| CPGS | |||||||

| Total (0–70) | 51.35 | 12.03 | 50.38 | 14.57 | 52.33 | 8.89 | 0.47 |

| Days with pain | 155.45 | 56.42 | 156.45 | 63.45 | 154.45 | 49.19 | 0.87 |

| QOLS (16–112) | 73.29 | 17.53 | 76.28 | 19.06 | 70.3 | 15.52 | 0.12 |

| HADS | |||||||

| Total (0–42) | 24 | 6.8 | 23.9 | 7.6 | 24.1 | 5.99 | 0.89 |

| Anxiety (0–21) | 13.61 | 3.45 | 13.58 | 3.60 | 13.65 | 3.34 | 0.92 |

| Depression (0–21) | 10.39 | 4.23 | 10.33 | 4.68 | 10.45 | 3.77 | 0.89 |

| MOS-SS | |||||||

| Sleep disturbance (0–100) | 74.84 | 16.69 | 75.11 | 16.21 | 74.57 | 17.39 | 0.88 |

| Daytime Somnolence (0–100) | 54.51 | 20.48 | 52.78 | 20.4 | 56.25 | 20.68 | 0.45 |

| Sleep adequacy (0–100) | 76.46 | 22.37 | 76.67 | 21.11 | 76.25 | 23.84 | 0.93 |

| Snoring (0–100) | 52.92 | 27.01 | 51.25 | 27.83 | 54.58 | 26.42 | 0.58 |

| Awaken short (0–100) | 54.79 | 23.29 | 53.75 | 22.48 | 55.83 | 24.33 | 0.69 |

| Quantity of sleep (Hours) | 5.31 | 1.26 | 5.23 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 1.1 | 0.53 |

| Sleep Problems I (0–100) | 69.22 | 11.96 | 69.15 | 11.13 | 69.29 | 12.87 | 0.63 |

| Sleep Problems II (0–100) | 68.19 | 12.07 | 67.5 | 11.52 | 68.89 | 12.72 | 0.50 |

FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; CSI: Central Sensitization inventory; PSQ: Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire; RSES: Rosenberg self-esteem scale; CPGS: Graded Chronic Pain Scale; QOLS: Quality of Life Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MOS-SS: Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale.

Correlations between CSI and PSQ scores with clinical variables.

| FIQ | CSI | PSQ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIQ | – | 0.48* | 0.38* |

| CSI | 0.48* | – | 0.25* |

| PSQ | 0.38* | 0.25* | – |

| RSES | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.01 |

| CPGS | 0.77* | 0.48* | 0.38* |

| QOLS | −0.57* | −0.40* | −0.35* |

| HADS anxiety | 0.50* | 0.40* | 0.34* |

| HADS depression | 0.50* | 0.40* | 0.39* |

| MOSS-SS Sleep Problem I | 0.35* | 0.34* | 0.16 |

| MOSS-SS Sleep Problem II | 0.33* | 0.35* | 0.16 |

p<0.01. FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; CSI: Central Sensitization inventory; PSQ: Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire; RSES: Rosenberg self-esteem scale; CPGS: Graded Chronic Pain Scale; QOLS: Quality of Life Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MOS-SS: Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale.

The bivariate analysis found a moderate significant association between CS, pain sensitivity and the impact of FMS on daily life and the different variables, regardless of the area of residence (rural/urban areas).

We found a moderate positive correlation between the impact of FMS and CS and pain sensitivity. A weak positive correlation was found between pain sensitivity and CS.

Strong correlations were found between the impact of FMS and pain and QoL, which were positive for pain and negative for QoL. We also found a moderate positive correlation between the impact of FMS and anxiety, depression and sleep quality.

Moderate positive correlations were found between CS and pain, anxiety, depression and sleep quality. A moderate negative correlation was found between CS and QoL. Pain sensitivity had a moderate positive correlation with pain, anxiety and depression, while the correlation with QoL was moderate but negative. No direct effects of pain sensitivity were observed on self-esteem and sleep quality.

DiscussionThe present study analyzed whether the impact of FMS was different depending on whether the participants resided in rural or urban areas, considering sociodemographic, clinical and symptomatologic factors. About participants recruitment, there were higher refusals to participate in rural population. Perhaps this could be due to the lower educational level and less contact with university research work. In previous studies, lower educational level was associated with maladjustment to pain in patients with chronic pain. This relationship seems to be mediated by catastrophism and the belief that pain is the sign of tissue damage.27 For this reason, we think that people with a lower educational level who have less contact with scientific research may not know the importance of investigation to find new methods and treatments that can improve the symptoms of FMS. In relation to sociodemographic data, the vast majority of the participants were women, with a mean age of 52.47 years. Our results only showed significant differences in terms of education level; the patients residing in urban areas had a higher education level than those residing in rural areas. These data are consistent with other studies with similar characteristics.8,12,28 Our results showed no differences between groups in relation to marital status or employment status, although they have been found in previous studies.12 Additionally, 50% of the participants were former smokers or current smokers, which was more prevalent among the participants from urban areas. According to recent literature, smoking is a risk factor for cognitive disfunction in patients with FMS. Furthermore, smokers with FMS have been shown to have reduced cognitive performance, worse QoL, increased sleep disturbance and an increased incidence of anxiety.29 In the present study, differences close to the level of significance were found among participants who smoked, which was higher among those residing in urban areas. A larger sample might have led to more significant differences. Our findings did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between groups for clinical variables. It would be interesting to consider alcohol consumption in rural/urban areas in future studies, since in some studies it has even been found that there is a relationship between low and moderate alcohol consumption and improvement in symptoms and quality of life in patients with FMS compared to no alcohol consumption.30 It would also be important to analyze whether this low or moderate consumption has an impact on the mental health of people with FMS in the medium or long term.

In terms of how geographical setting influences FMS, the literature review did not reveal consistent data. Twenty years ago, a study showed that the most important determinants for the presence of FMS in the Spanish population were, in order of importance, being a woman, having other chronic diseases and living in a rural area.31 However, in more recent publications by the same research group, no associations were found between suffering from FMS and living in a rural area.14 In previous literature on chronic diseases, the rural sample suffered from poorer mental health with more symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to the urban population. In addition, unemployment, lower educational level and increased anxiety were associated with poorer mental health. A recent study, published while we were conducting our research, analyzed the link between FMS and geographical setting, had similar methodological characteristics and also used a Spanish sample. The researchers found that there were differences in age, educational level, employment status, marital status, disease acceptance, pain and physical and mental fatigue between patients from urban and rural areas. The rural population was older and consisted mainly of married homemakers with a lower educational level.12 The link between rural area of residence and lower educational level was also evident in our study. This disparity in the results may be due to geographical differences in the country or region of study; despite differentiating between rural and urban areas, all of our participants live in the same province (Jaen, Spain) and are therefore likely to have somewhat similar lifestyles. Furthermore, the population density of the urban area studied (269.24inhabitants/km2 in Jaén) is relatively low compared to large cities in the same Spanish country (5265.91inhabitants/km2 in Madrid or 4875.08inhabitants/km2 in Seville). This could explain why there are no differences between the groups, except for education level. In the other study carried out in Spain, the sample was selected from different areas across the country, without specifying the patients’ exact areas of residence, making it difficult to establish similarities.

Our results also showed that there were interesting low-to-moderate correlations between CS, pain sensitivity and the impact of FMS on daily life and other symptoms or conditions of FMS patients. Regarding the impact of FMS on daily life, a mean total score of 67.61 (17.76) was calculated, similar to other recently published research that used a sample with similar characteristics.28 In our study, FMS has a significant relationship with CS, which is very common with this syndrome.28

Our participants experience high CS and high sensitivity to pain. In line with this finding, previous studies have shown that FMS patients have greater neuronal activation in the pain processing areas of the brain compared with controls.32 Furthermore CS, along with other neural and psychosocial mechanisms, such as abnormalities in ascending and descending central pain pathways and changes at neurotransmitters level, explain altered and increased sensitivity to pain. Concurring with existing literature,20 we found a moderate positive correlation between the impact of FMS on daily life and pain sensitivity. However, a weak correlation was found between pain sensitivity and CS, in contrast to recent literature,20 in which the relationship between both variables was greater than in our results.

In addition, strong correlations were found between the impact of FMS and other study variables such as pain and QoL, for which the correlation was positive and negative respectively. This negative correlation is very common in existing literature, which has shown that patients with FMS have a worse QoL than the general population. Moreover, Pérez-de-Heredia-Torres M. et al.33 concluded that women with FMS had greater disability and reduced QoL and required more assistance to perform specific activities of daily life than healthy women. This moderate negative correlation was also found between CS and pain sensitivity variables and QoL, reflecting how greater pain sensitivity and CS lead to worse QoL.

Furthermore, our results illustrated that the impact of FMS on daily life had a strong, positive and direct association with anxiety and depression, factors commonly shown in previous studies12 to have a bidirectional relationship with FMS. In the most recent article published in the Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, an increasing trend of depression, anxiety, stress, and somatoform symptoms was observed with an increase in the severity of FMS when patients were compared according to FMS severity scores. Sleep also deteriorated with increasing severity of FMS and the QOL also deteriorated in all the domains with increasing severity.34

In line with other research,35 our study found moderate positive correlations between CS and pain variables and anxiety and depression variables. Pain sensitivity had a moderate positive correlation with pain, anxiety and depression; the latter had an important impact on pain sensitivity, as proven in previous research.

Lastly, our results showed a moderate correlation between the impact of FMS on sleep quality. Similar results were reported in other studies.36 Sleep quality was also correlated with CS, which is very common in patients with chronic diseases.

The present study has some limitations to consider. First, the study has a cross-sectional correlational design, thus preventing us from drawing causal inferences. Moreover, the nature of the study did not allow us to monitor the variables over time to detect potential changes and differences between the groups. Second, a larger sample size could have shown statistically significant differences between the groups. A greater number of patients, especially from rural areas, declined to participate in the study, and patients over 65 years of age and those with mental health problems were also excluded. This may have influenced some of the results. However, due to the exploratory nature of the study and the high number of variables included in the analysis, very relevant information has been provided on the relationship between determining variables in patients with FMS. The importance of this study is based on the analysis of the correlation between the impact of FMS, CS and pain sensitivity, providing relevant information for a better understanding and management of FMS.

To our knowledge, this is the second study that analyzes how the characteristics of geographical setting influence the management of FMS. In light of these findings, future research should be conducted with larger samples to determine the existence and cause of consistent differences between these patients, by analyzing how geographical setting can influence the development and management of chronic diseases such as FMS.

ConclusionsNo differences were found between Fibromyalgia Syndrome rural/urban groups for sociodemographic and clinical variables, except for educational level. There is a low-to-moderate significant association between the impact of FMS, CS and pain sensitivity in patients with FMS. Our results show that the impact of FMS on daily life, CS and pain sensitivity are moderately associated with anxiety and depression. There is a strong correlation between the impact of FMS, pain and QoL.

- •

Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is defined as a chronic disorder of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of generalized pain, and associated with numerous symptoms such as fatigue, anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality.

- •

Some existing literature has found a link between FMS patients’ area of residence and the impact of the disorder. However, these findings have been inconsistent.

- •

No differences were found between FMS rural/urban groups for sociodemographic and clinical variables, except for educational level.

- •

There is a significant association between the impact of FMS, central sensitization, and pain sensitivity in patients with FMS, regardless of their area of residence. Besides, there is a very strong association is between the impact of FMS and quality of life.

The research protocol was approved by the University of Jaén's Research Ethics Committee (Code ENE.22/1.PRY) and was carried out in strict compliance with the ethical standards and procedures for research involving human subjects of the World Health Organization (Declaration of Helsinki). All participants received information about the study and signed a written informed consent form acknowledging their voluntary participation.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Jaén Fibromyalgia Association (AFIXA) and the Fisio Mas Clinic for their availability and commitment, especially all the participants in this study.