There has been a significant global increase in the prevalence of fatty liver disease, particularly nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This increase is largely driven by the worldwide increase in obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and other metabolic disorders [1–4]. In response to these trends, there has been a shift in terminology to better reflect the primary causes and reduce the stigma associated with the term “nonalcoholic”. Consequently, NAFLD has been redefined as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [5]. This new nomenclature emphasizes that the disease primarily arises from metabolic dysfunction rather than alcohol consumption, which can help to focus both clinical and public health efforts on the metabolic roots of the condition. Furthermore, this shift in terminology recognizes the importance of accurately identifying the spectrum of liver diseases that can coexist with metabolic risk factors. To further illustrate the relationship between metabolic dysfunction and alcohol intake in liver disease development, a new concept, metabolic-associated alcoholic liver disease (Met-ALD), was introduced. Met-ALD refers to liver disease in individuals who consume alcohol above the threshold for MASLD but also exhibit metabolic risk factors such as obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia [6,7]. This refined classification offers a more detailed understanding of the disease mechanisms and can help guide more targeted therapeutic approaches.

While previous findings on NAFLD remain applicable under the new MASLD definition [8], studies on MASLD are growing [9,10], and the concept of Met-ALD is still relatively new, with few studies available. A noticeable gap remains in studies that directly compare the clinical features of MASLD and Met-ALD. Although the revised terminology enhances our understanding of these conditions, further research is needed to clarify the unique characteristics, progression, and outcomes of each category fully.

Given the frequent use of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database in recent NAFLD research [11–13], and the strong diagnostic value of liver ultrasound transient elastography in steatotic liver disease (SLD) [14–16], this study aimed to compare the demographic and clinical features of MASLD and Met-ALD using the NHANES database. Additionally, we examined the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases across these groups.

2Materials and Methods2.1Study design and data collectionThis study used data from the 2017 to 2020 cycles of the NHANES, a cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics under the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NHANES collects data through interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory assessments, employing a complex, multistage, stratified, and clustered probability sampling method. The study was approved by the CDC's Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent [11].

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we gathered demographic data, examination data (including blood pressure, body measurements, and liver ultrasound transient elastography), laboratory data (such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL), cholesterol, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis C RNA and standard biochemistry profiles), and questionnaire data (covering alcohol use, diabetes, hepatitis, medical conditions, and prescription medications) from a total of 8965 participants. After excluding those with incomplete data, patients with viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, or other liver diseases, and participants without features indicative of SLD or MASLD cirrhosis, we ultimately included 3755 individuals in the analysis. This cohort consisted of 3452 individuals with MASLD, 185 with Met-ALD, 78 with alcoholic liver disease (ALD), and 40 with cryptogenic SLD.

2.2Diagnosis of liver steatosis and fibrosis stagesAll participants in the study had valid liver elastography measurements that were conducted at the NHANES Mobile Examination Center using the FibroScan® model 502 V2 Touch. Depending on the participant's body type, either a medium (M) or an extra-large (XL) probe was used. The controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) value was applied to evaluate liver steatosis, with thresholds set at 248 dB/m for mild steatosis (S1), 268 dB/m for moderate steatosis (S2), and 294 dB/m for severe steatosis (S3) [14].

The liver stiffness measurement (LSM) value was used to assess liver fibrosis. For fibrosis staging, an LSM value of 8.2 kPa or greater indicated stage ≥ F2 (significant fibrosis), 9.7 kPa or greater indicated stage ≥ F3 (advanced fibrosis), and 13.6 kPa or higher was used to classify cirrhosis (F4) [15].

2.3Definitions of the MASLD, Met-ALD, ALD and cryptogenic SLD categoriesA standard drink was defined as containing 14 g of pure alcohol, and the data from the alcohol use questionnaire were converted accordingly. Based on the diagnostic criteria from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [6], patients were categorized as having MASLD if they had a CAP value of ≥ 248 dB/m or a CAP value of < 248 dB/m with an LSM > 13.6 kPa, along with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor (BMI adjusted according to Asian-specific cutoffs), and consumed less than 20 g of alcohol per day for women or less than 30 g per day for men. When alcohol consumption increased to 20–50 g/day in women and 30–60 g/day in men, the condition was classified as Met-ALD. For ALD diagnosis, the CAP value needed to be ≥ 248 dB/m, with alcohol intake exceeding 50 g/day in women and 60 g/day in men, with or without the presence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Additionally, patients with a CAP value of ≥ 248 dB/m who did not have other liver diseases, excessive alcohol consumption, or cardiometabolic risk factors were classified as having cryptogenic SLD.

2.4Diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease (CHD), heart attack and T2DMIn this study, we obtained the average systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values from the blood pressure data. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg [17], or the use of antihypertensive medications based on the participants' medication records. Hyperlipidemia was diagnosed through laboratory tests if any of the following criteria were met: total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 6.2 mmol/L, triglycerides (TG) ≥ 2.3 mmol/L, HDL < 1 mmol/L [18], or current use of lipid-lowering medications. Additionally, fasting plasma glucose (GLU) levels ≥ 7 mmol/L [19] along with information from the diabetes questionnaire data and the use of medication for T2DM or related complications, were used to diagnose T2DM and its associated complications. The incidence rates of CHD and heart attack were obtained according to data from the medical condition questionnaire.

2.5Data weighting and statistical analysisGiven the NHANES complex multistage sampling design, special sample weights (WTMECPRP) were applied in all analyses to more accurately reflect the United States population using the survey package in R. After weighting, the total sample size was 108,189,678 individuals, including 97,038,804 with MASLD, 7639,744 with Met-ALD, 2420,954 with ALD, and 1090,176 with cryptogenic SLD (Fig. 1). All subsequent statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.1. To assess significance across multiple groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test were used. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations between variables and the prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, CHD, and T2DM in MASLD and Met-ALD patients. Categorical variables are reported as weighted counts and proportions, whereas continuous variables are presented as weighted means ± standard errors (SEs). Statistical P values were set at 0.05.

3Results3.1Demographic and clinical characteristics across SLD subtypes3.1.1Demographic characteristicsTable 1 summarizes the demographic profiles of participants across the MASLD, Met-ALD, ALD, and cryptogenic SLD groups. The participants with MASLD and Met-ALD were significantly older than those with cryptogenic SLD (mean age: MASLD 50.63 ± 0.72 years, Met-ALD 48.19 ± 1.72 years, cryptogenic SLD 40.33 ± 2.21 years, P = 0.004). A sex-based difference was observed: MASLD had a greater proportion of females (50.78 %), whereas males predominated in the Met-ALD (86.29 %), ALD (90.11 %), and cryptogenic SLD (66.67 %) groups (P = 0.001). In terms of race, non-Hispanic whites constituted the majority across all groups. However, Asian individuals were more frequently represented in the MASLD (5.28 %) and cryptogenic SLD (5.56 %) groups than in the Met-ALD (1.27 %) and ALD (0.97 %, P = 0.008) groups.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the MASLD, Met-ALD, ALD, and cryptogenic SLD categories.

Note: The Kruskal-Wallis test and the chi-square test were employed to assess the significance among multiple groups, with ALD serving as the reference group. The Mann-Whitney U test and the chi-square test were employed to assess the significance between the MASLD and Met-ALD groups. Categorical variables are reported as weighted counts and proportions, whereas continuous variables are presented as weighted means ± SEs.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CR, creatinine; F2, significant fibrosis; F3, advanced fibrosis; F4, cirrhosis; FIB-4, fibrosis 4 score; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; GLU, blood glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; Met-ALD, metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease; PLT, platelet count; S1, mild steatosis; S2, moderate steatosis; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; S3, severe steatosis; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SLD, steatotic liver disease; TBIL, total bilirubin; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

As shown in Table 1, the MASLD group had the highest body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and CAP values (mean: 308.34 ± 1.28 dB/m), indicating more severe hepatic steatosis. This was followed by Met-ALD (307.66 ± 5.50 dB/m), ALD (307.84 ± 7.09 dB/m), and cryptogenic SLD (263.26 ± 3.89 dB/m, P < 0.0001). We further classified fatty liver based on CAP values and found that S3 was predominant in MASLD (56.78 %), Met-ALD (45.38 %), and ALD (53.47 %), whereas cryptogenic SLD had more S1 cases (67.81 %, P = 0.003). No significant difference was found in the distribution of steatosis grades between the MASLD and Met-ALD groups (P = 0.657). Regarding liver fibrosis assessment, no significant differences were observed in LSM values, fibrosis 4 (FIB-4) scores or liver fibrosis stages across all subtypes.

Additionally, liver enzyme levels varied by group: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) were elevated in the Met-ALD and ALD groups compared with those in the MASLD group, with the lowest levels observed in the cryptogenic SLD group (P = 0.001, P = 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively).

These results suggest that while MASLD patients have the most pronounced obesity-related features and highest liver fat accumulation, liver enzyme levels and TBIL are higher in alcohol-related liver diseases (Met-ALD and ALD).

3.1.3Cardiometabolic parameters and comorbiditiesMASLD patients presented the most adverse metabolic profiles among all subtypes. Specifically, the MASLD group had the lowest HDL levels and highest GLU levels (P < 0.0001 for both). When comparing MASLD with Met-ALD, MASLD patients had significantly lower HDL levels (P < 0.0001), although no significant difference was found in GLU levels between the two groups (P = 0.335). The TC and TG levels were significantly elevated in the MASLD and ALD groups, with the highest levels in the ALD group (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.002, respectively). Additionally, the blood pressure was significantly higher in the Met-ALD and ALD groups compared to the MASLD and cryptogenic SLD groups (P < 0.0001).

To further explore cardiometabolic comorbidities, we analyzed the prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, CHD, heart attack, T2DM, and complications of T2DM across MASLD, Met-ALD and ALD groups (Table 2). The results showed that T2DM was significantly more prevalent in the MASLD group (19.38 %) compared to Met-ALD (9.39 %, P = 0.002) and ALD (7.69 %). Moreover, all cases of T2DM complications were reported exclusively in the MASLD group (0.94 %), although the overall number was low and the difference was not statistically significant. The prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, CHD, and heart attack did not differ significantly between the groups. These findings suggest that metabolic dysfunction, rather than cardiovascular disease burden, is the predominant feature distinguishing MASLD from other liver disease subtypes.

Prevalence of various cardiometabolic diseases across different groups.

Note: The chi-square test was employed to assess the significance of differences between multiple groups. Categorical variables are reported as weighted counts and proportions.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; Met-ALD, metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease; SLD, steatotic liver disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Among MASLD patients with a CAP ≥ 248 dB/m, 16.88 % were classified as S1, 25.99 % as S2, and 57.13 % as S3. The analysis revealed no significant differences in age or race between the S1, S2, and S3 subgroups. However, the S3 subgroup had a greater proportion of males (57.02 %, P = 0.001). As the grade of liver steatosis increased, there were significant rises in BMI, WC, LSM, and liver enzyme levels (ALT, AST, and GGT). Notably, patients in the S3 subgroup had a significantly greater proportion of F2-F4 fibrosis compared to the other groups (P < 0.0001).

Lipid profiles also worsened with increasing steatosis grade: HDL levels decreased, while TG levels increased, which corresponded with a greater prevalence of hyperlipidemia in the S3 group (P < 0.0001). Similarly, GLU levels increased as liver fat accumulation progressed, and the prevalence of T2DM was significantly higher in the S3 subgroup (P < 0.0001). Although there were no statistically significant differences in specific T2DM-related complications across the groups, patients with S3 steatosis showed a higher overall prevalence of T2DM complications compared to other steatosis subgroups. Additionally, hypertension was more prevalent in the S3 subgroup (P = 0.001), although the rates of CHD and heart attack were similar across all subgroups (Table 3). These findings highlight the progressive nature of metabolic disturbances with worsening liver steatosis, particularly in the S3 subgroup, reinforcing the importance of early detection and management in these high-risk patients.

Features of the MASLD patients segregated by the degree of estimated liver steatosis.

Note: The Kruskal-Wallis test and the chi-square test were employed to assess the significance of differences between multiple groups. Categorical variables are presented as weighted counts and proportions, whereas continuous variables are presented as weighted means ± SEs.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CHD, coronary heart disease; F2, significant fibrosis; F3, advanced fibrosis; F4, cirrhosis; FIB-4, fibrosis 4 score; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; GLU, blood glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; S1, mild steatosis; S2, moderate steatosis; S3, severe steatosis; TBIL, total bilirubin; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WC, waist circumference.

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, patients with Met-ALD exhibited trends similar to those observed in MASLD. Specifically, as the steatosis grade increased, BMI, WC, LSM, ALT, and GGT levels significantly increased. The differences in fibrosis stage among the subgroups were not statistically significant. In terms of comorbidities, the prevalence of hypertension was notably greater in the S3 subgroup (P = 0.026). While other conditions, such as hyperlipidemia and T2DM, also appeared more frequent in this group, the differences did not reach statistical significance.

These findings suggest that the metabolic burden associated with hepatic fat accumulation may be more severe and clinically relevant in MASLD than in Met-ALD, emphasizing the need for subtype-specific risk stratification and management strategies.

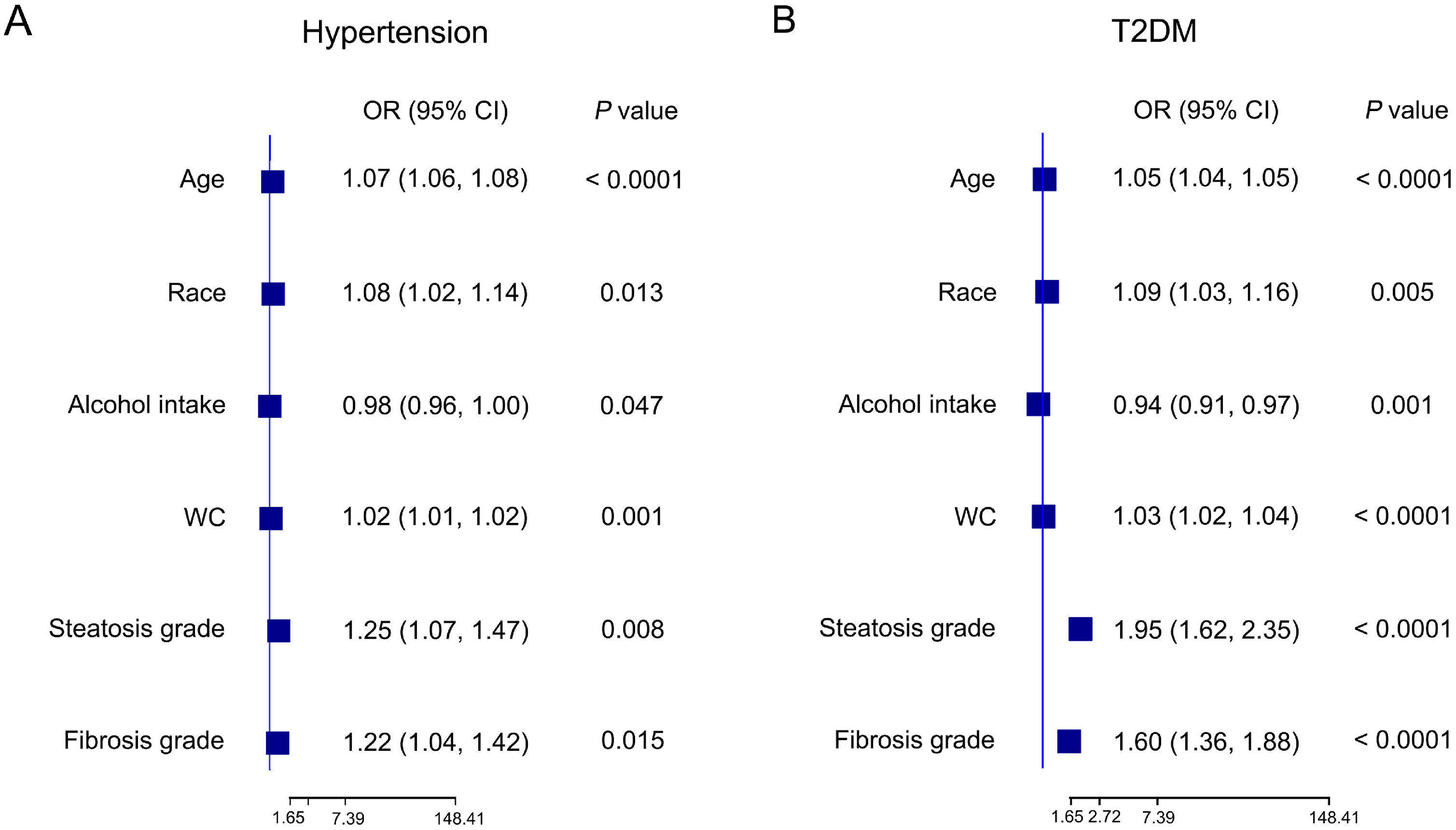

3.3Risk of the incidence of cardiometabolic diseases and advanced fibrosis in MASLD patients3.3.1Risk factors associated with hypertensionTo investigate the risk factors for hypertension in MASLD patients, we performed both univariate and multivariate regression analyses. In the univariate analysis, several factors were significantly correlated with hypertension, including age, race, WC, alcohol intake, CAP, steatosis grade, and fibrosis grade (Table 4). After assessing multicollinearity and selecting variables with a variance inflation factor less than 5, the final multivariate model included age, race, WC, alcohol intake, steatosis grade, and fibrosis grade. The multivariate results revealed that age (OR: 1.07, 95 % CI: 1.06–1.08, P < 0.0001), WC (OR: 1.02, 95 % CI: 1.01–1.02, P = 0.001), steatosis grade (OR: 1.25, 95 % CI: 1.07–1.47, P = 0.008) and fibrosis grade (OR: 1.22, 95 % CI: 1.04–1.42, P = 0.015) were strong independent risk factors for hypertension. Interestingly, alcohol intake was found to be a protective factor (OR: 0.98, 95 % CI: 0.96–1.00, P = 0.047). Moreover, non-Mexican ethnic groups were at greater risk than Mexican ethnic groups (Fig. 2a). These results underscore the role of liver fat accumulation and metabolic health in the development of hypertension, with moderate alcohol intake serving as a potential modifiable protective factor.

The correlation between various variables and the prevalence of different cardiometabolic diseases in MASLD patients.

Note: Univariate regression analysis was performed.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; OR, odds ratio; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WC, waist circumference.

Forest plot illustrating the correlation between various factors and the prevalence of hypertension (A) and T2DM (B) in MASLD patients. Multivariate regression analysis was subsequently performed. CI, confidence interval; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; OR, odds ratio; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WC: waist circumference.

Additionally, our analysis of risk factors for hyperlipidemia and CHD in patients with MASLD revealed that older age (OR: 1.01, 95 % CI: 1.00–1.01, P < 0.0001) and higher steatosis grade (OR: 1.10, 95 % CI: 1.07–1.13, P < 0.0001) were significant predictors of hyperlipidemia, and women were less likely to develop hyperlipidemia (P = 0.003) and CHD (P = 0.007, Table 4).

3.3.2Risk factors associated with T2DMIn MASLD patients, several factors were significantly associated with the development of T2DM. Univariate analysis identified age, race, BMI, WC, alcohol intake, LSM, steatosis grade, and fibrosis grade as key variables associated with T2DM (Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, alcohol consumption emerged again as a protective factor (OR: 0.94, 95 % CI: 0.91–0.97, P = 0.001). Conversely, higher steatosis grade (OR: 1.95, 95 %CI: 1.62–2.35, P < 0.0001), fibrosis grade (OR: 1.60, 95 %CI: 1.36–1.88, P < 0.0001), and older age (OR: 1.05, 95 % CI: 1.04–1.05, P < 0.0001) were independently associated with increased risk of T2DM. Like those with hypertension, non-Mexican ethnic groups were at greater risk than their Mexican counterparts (Fig. 2b). These results highlight the strong association between hepatic disease severity and glucose metabolism dysregulation.

3.3.3Risk factors associated with advanced fibrosis (≥ F3)We also explored the determinants of advanced liver fibrosis in MASLD patients. As shown in Table 5, univariate analysis identified several significant risk factors, including BMI, WC, CAP, ALT, AST, and GGT. Metabolic parameters (HDL and GLU), and T2DM also showed strong associations with advanced fibrosis. In multivariate analysis, WC (OR: 1.06, 95 %CI: 1.05–1.07, P < 0.0001), AST (OR: 1.05, 95 % CI: 1.04–1.07, P < 0.0001), and GGT (OR: 1.01, 95 % CI: 1.00–1.02, P = 0.0003) were identified as robust independent predictors of advanced fibrosis. Additionally, T2DM remained an independent and strong risk factor (OR: 2.27, 95 % CI: 1.76–2.93, P < 0.0001), highlighting the close link between metabolic dysfunction and fibrosis progression.

Correlations between clinical variables and the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in patients with MASLD and Met-ALD.

Note: Both univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CHD, coronary heart disease; CR, creatinine; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; GLU, blood glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; Met-ALD, metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease; PLT, platelet count; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SLD, steatotic liver disease; TBIL, total bilirubin; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WC, waist circumference.

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases in Met-ALD patients. The results showed that age (OR: 1.07, 95 % CI: 1.04–1.10, P < 0.0001), race (OR: 1.50, 95 % CI: 1.05–2.13, P = 0.013), CAP (OR: 1.02, 95 % CI: 1.01–1.03, P = 0.047), and liver fibrosis grade (OR: 5.15, 95 % CI: 1.91–13.92, P = 0.001) were independent predictors of hypertension (Table 6, Fig. 3a). Unlike in MASLD patients, alcohol intake was no longer observed to be a protective factor in this group.

Correlations between various variables and the prevalence of different cardiometabolic diseases in Met-ALD patients.

Note: Univariate regression analysis was subsequently used.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; Met-ALD, metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WC, waist circumference.

Forest plot illustrating the correlation between various factors and the prevalence of hypertension (A) and T2DM (B) in Met-ALD patients. Multivariate regression analysis was subsequently performed. CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CI, confidence interval; Met-ALD, metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

For T2DM, the multivariate analysis identified age (OR: 1.07, 95 % CI: 1.03–1.11, P = 0.005), WC (OR: 1.06, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.10, P = 0.014), and liver fibrosis grade (OR: 3.01, 95 % CI: 1.93–4.70, P = 0.008) as significant risk factors, while CAP and steatosis grade were not significantly associated with T2DM risk in Met-ALD patients (Table 6, Fig. 3b). Additionally, liver fibrosis grade was associated with hyperlipidemia (OR: 1.13, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.27, P = 0.026), and LSM was a significant predictor of CHD (OR: 1.01, 95 % CI: 1.00–1.01, P = 0.006). These results reinforce the central role of liver fibrosis and stiffness in the development of cardiometabolic diseases in patients with Met-ALD.

3.4.2Risk factors associated with advanced fibrosisWe also examined the predictors of advanced fibrosis in patients with Met-ALD. According to Table 5, hypertension was significantly associated with advanced fibrosis in Met-ALD patients (OR: 8.81, 95 % CI: 1.50–133.50, P = 0.040), suggesting a synergistic relationship between cardiovascular stress and liver fibrosis in this population. Additionally, ALT (OR: 1.03, 95 % CI: 1.01–1.06, P = 0.002) and T2DM (OR: 13.3, 95 % CI: 2.66–85.71, P = 0.002) were identified as independent risk factors for advanced fibrosis. In contrast to MASLD, AST and GGT did not remain significant in the multivariate model, possibly due to differing liver injury patterns in alcohol-associated liver disease.

Overall, these results reinforce the need for integrated management strategies that address both hepatic and cardiometabolic health in Met-ALD.

4DiscussionIn this representative sample of the United States population, we observed distinct demographic and clinical differences among patients with MASLD, Met-ALD, ALD, and cryptogenic SLD. Patients with Met-ALD, ALD, and cryptogenic SLD were generally younger and predominantly male compared to those with MASLD. This may reflect underlying behavioral or biological sex-related differences in alcohol consumption and metabolic disease susceptibility. In the comparative analyses between the MASLD and Met-ALD groups, patients with MASLD had significantly higher BMI, WC, and prevalence of T2DM, which is consistent with the strong associations of MASLD with obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Interestingly, despite having a lower degree of liver steatosis—as measured by CAP—Met-ALD patients exhibited significantly higher levels of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, and GGT), than did the MASLD group. This discrepancy suggests that alcohol-related liver injury is more hepatocellular in nature and may not be fully reflected by steatosis measurements alone [20,21].

With respect to cardiometabolic outcomes, MASLD patients presented the highest prevalence of T2DM and related complications, which was consistent with their unfavorable metabolic profile. Steatosis and fibrosis severity were independently associated with T2DM risk, suggesting a potential role of hepatic fat and fibrosis in modulating systemic insulin sensitivity. Moreover, alcohol consumption showed an inverse relationship with T2DM risk in MASLD, which is consistent with prior studies suggesting that modest alcohol intake may confer some metabolic benefits, such as improved insulin sensitivity or reduced systemic inflammation [22,23]. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the observational nature of the data and the possibility of residual confounding. Although the overall prevalence of other cardiometabolic conditions (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, CHD) did not differ significantly between the MASLD, and Met-ALD groups, stratified analyses revealed key associations that are consistent with findings from previous studies [24,25]. In MASLD, higher grades of steatosis and fibrosis were linked to an increased prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia. In Met-ALD, fibrosis grade emerged as a central risk factor for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM. These results support the hypothesis that liver fibrosis represents a key node in the interaction between liver health and systemic metabolic disease.

Importantly, our study also identified independent risk factors for the development of advanced liver fibrosis (≥ F3) in patients with MASLD and Met-ALD. The presence of T2DM was significantly associated with advanced fibrosis in both groups, consistent with previous findings [26] and underscoring the critical role of metabolic control in preventing fibrosis progression. Additionally, advanced fibrosis was strongly associated with hypertension in patients with Met-ALD, suggesting potential differences in the underlying mechanisms of fibrosis between purely metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, as the sample is representative of the United States population, the findings may not be applicable to other populations, settings, or samples. Second, although transient elastography offers a reliable noninvasive alternative, the diagnostic accuracy of LSM may be influenced by factors such as higher BMI or greater hepatic steatosis, which could lead to overestimation of fibrosis, particularly in patients with MASLD. Moreover, the absence of histological data in NHANES prevents us from fully ruling out these confounding effects. Although the FIB-4 score was also utilized to complement LSM, it may be less sensitive for detecting early-stage fibrosis and its performance can vary across different liver disease subtypes [27–29]. Third, the NHANES database does not include comprehensive data on the use of steatogenic medications. As patients classified as cryptogenic SLD may have underlying steatogenic medication use that was not captured, this could introduce additional variability in the classification. Finally, survival outcomes could not be evaluated due to incomplete follow-up data from the NHANES during the study period. As a result, we were unable to assess long-term prognoses across SLD subtypes.

5ConclusionsThis NHANES-based analysis highlights key differences between MASLD and Met-ALD. MASLD was more closely linked with obesity and T2DM, whereas Met-ALD patients presented increased liver enzymes and blood pressure, reflecting the dual impact of alcohol and metabolic stress. Moderate alcohol intake appeared to reduce T2DM risk in MASLD, although this finding requires cautious interpretation. Advanced fibrosis in MASLD patients was most strongly associated with T2DM, whereas in Met-ALD patients, hypertension emerged as the dominant risk factor. These findings emphasize the importance of liver elastography not only for fibrosis assessment but also as a tool for cardiometabolic risk stratification in clinical practice.

FundingThis research was supported by Investigator-Initiated Trial of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (No. 2024-YN006), Youth Cultivation Program for Basic Research supported by Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (No. 2024JC017), and the National Natural Science Fund of China (No. 82302217).

None.

We sincerely appreciate the great work of the NHANES collaborators.