Autoimmune liver diseases (AILD), encompass a group of immune-mediated inflammatory conditions including primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), and overlaps between these subtypes.

PBC is characterized by progressive destruction of intra-hepatic bile ducts, leading to cholestasis and, if untreated, cirrhosis. PBC patients often experience fatigue and pruritus as presenting symptoms, and have an elevated alkaline phosphatase. PSC is primarily associated with inflammation and fibrosis of both intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts. PSC similarly can present with fatigue as well as pruritus in the setting of an elevated alkaline phosphatase, and is also associated with cholangiocarcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease. AIH is characterized by immune-medicated inflammation and destruction of hepatocytes, and can present with a wide variety of gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms in the setting of a hepatocellular predominant pattern of liver injury.

Global incidence rates vary, with PBC ranging from 0.84 to 2.75 per 100,000, PSC from 0.1 to 4.39 per 100,000, and AIH from 0.4 to 2.39 per 100,000 [1]. Presentation is variable, ranging from being clinically silent to severe symptomatic disease characterized by abdominal pain, fatigue, jaundice, and pruritus[2]. Curative therapies for PBC include ursodeoxycolic acid which is first line treatment with a recommendation of 13 to 15 mg/kg/day, obeticholic acid or newer agents such as seladepar or elafibranor; patients usually require lifelong therapy to manage disease progression and prevent complications [[2]]. For the other AILDs, AIH is managed with various immunosuppressive therapies, while liver transplantation remains the only established option for PSC [1,2]

AILD impact quality of life through disease morbidity, treatment burden, and the psychological impact of a rare, incurable condition. Symptoms including fatigue, pruritus, and cognitive impairment are particularly challenging, often exacerbated by side effects from chronic immunosuppression [3]. AILD are associated with increased prevalence of anxiety and major depressive symptoms [4,5]. These comorbidities further impair quality of life and can contribute towards reduced treatment adherence and potentially accelerate disease progression [6]. AILD patients face added stress from the disease's unpredictability, lack of a cure, and potentially shortened life expectancy [7].

The impact of AILDs on quality of life, however, varies by subtype [8]. AIH patients primarily experience fatigue, while pruritus and cognitive impairment are relatively uncommon [9,10]. Patients with PBC are prone to severe pruritus, severe fatigue, and cognitive issues which can significantly affect daily life, while PSC patients report fatigue and pruritus that are generally less severe and prevalent, however, abdominal pain is often highly prevalent [11]. These differences, although reported previously in literature separately, have never been directly compared between the types of AILD.

While the mainstay of AILD management has been evolving in recent years, working to improve and understand historical trends in the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of AILD patients is also crucial. The Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CDLQ), the most widely utilized symptom-based tool, calculates an overall score based on patients’ abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, emotional functioning, and worry. Lower scores imply a more debilitating symptom burden [12]. The European Quality-of-Life 5-Dimensions 5-Level (EQ-5D-5 L) questionnaire has been validated across a range of chronic liver diseases [13,14]. The EQ-5D-5 L assesses quality of life across five dimensions including mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety and depression to calculate a utility index, which can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life years [14]. Similar to the CDLQ, lower scores imply a more debilitating impact on the corresponding domain, indicating a greater reduction in quality of life.

Despite extensive HRQOL research in liver diseases, targeted studies on AILD symptom burden and its influencing factors remain limited. This prospective study examined symptom burden and its correlations with demographic factors, biochemical markers, and multiple questionnaire scores (CLDQ and EQ-5D-5 L) in PBC, PSC, and AIH over a seven-year, single-center cohort. The AILD diagnosis was made in accordance with AASLD guidelines [2,11].

2Material and Methods2.1Study designA total of 466 patients with AILD were enrolled between January 2018 and July 2024 in this non-interventional, prospective cohort study at the Liver Research Center of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Patients completed CLDQ and EQ-5D questionnaires during each medical appointment, resulting in 2420 responses, with an average of 2.8 responses per questionnaire.

2.2Ethical statementThe study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice. All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the BIDMC Institutional Review Board (IRB), protocol number 2018P00019, with the latest consent approval date of 19 December 2023. Patient Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.3Study sampleThe study included patients over 18 years old that were diagnosed with autoimmune and cholestatic chronic liver diseases, such as AIH, PBC, and PSC, and overlaps among these conditions, in the United States. Patients with secondary diagnosis of Metabolic-associated Steatotic Liver Disease were included in the study, but we excluded patients with primary or secondary diagnoses of any other chronic liver disease. Patients with history of previous LT, multiple solid organ transplant such as heart or kidney, acute liver failure at diagnosis, or expected life expectancy of < 6 months were also excluded. AILD diagnosis was made or confirmed at enrollment following the guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, which were also used for patient management and treatment.

Before participation, patients were informed of the study’s purpose and protocol. Patients were recruited during their annual appointments, with an approximate enrollment rate of 78 %. The total number of patients invited has been an estimate of 600 patients with primary AILD. At the time of diagnosis, each participant completed an initial questionnaire, followed by yearly assessments throughout the follow-up period. Data collection included age, gender, race, BMI, diagnostic laboratory values (ALT, AST, ALP, creatinine, bilirubin, albumin), presence of secondary liver disease, cirrhosis, liver stiffness, and liver biopsy findings stratified by METAVIR biopsy score (Fig. 1).

2.4Statistical analysisFor Table 1, we stratified clinical and demographic characteristics by AILD etiology, data was taken from diagnosis visit. We utilized Kruskal-Wallis’s test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ²) for categorical variables. Continuous variables are shown as mean (SD) or median (IQR), and categorical variables as percentages.

Baseline characteristics.

AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; IQR: Interquartile Range; Kpa: Kilopascal; MASLD: Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease; MASH: Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis; N: Number; PBC: Primary Biliary Cholangitis; PSC: Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; SD: Standard Deviation.

We compared CLDQ domains with one-way ANOVA and applied Bonferroni correction for post hoc testing. EQ-5D UI and VAS were compared using Kruskal-Wallis’s test, and categorical variables with Pearson’s chi-squared test. A P-value of <0.05 was deemed significant.

To identify CLDQ survival predictors, we performed univariate and multivariate (MVA) linear regression analyses, including clinically relevant variables and those significant at the bivariate level (partial regression [0.1], partial elimination [0.05]). Results are presented as coefficients (b) with 95 % CIs.

For HRQOL predictors using EQ-5D, we used a Tobit regression model due to the ceiling effect of the UI score. All analyses used a significance level of <0.05 (two-tailed) and were conducted with Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp LP).

2.5Assessment of health-related quality of life indicators using the chronic liver disease questionnaireThe CLDQ is a tool for measuring HRQOL in chronic liver disease patients, consisting of 29 items across six domains: abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, emotional function, and worry. Each domain has 3–8 questions rated on a 1–7 Likert scale, with 1 indicating constant trouble and 7 indicating no trouble. The overall score is the average of these domains, with higher scores reflecting better HRQOL. Validated for PBC and PSC, a total score below 5 indicates poor HRQOL [15,16].

2.6Assessment of health-related quality of life indicators using the euroqol 5-dimensions and euroqol visual analogue scaleThe EuroQoL group developed two HRQOL measures: the visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) and the 5-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D). The EQ-VAS asks respondents to rate their health from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). A score below 60 indicates poor HRQOL. The EQ-5D assesses five dimensions—mobility, self-care, activity, pain, and anxiety/depression—rated from 1 (no problems) to 3 (extreme problems). Both tools are validated for liver transplant candidates and recipients.

3Results3.1Study populationOur study included 466 AILD patients (230 AIH, 118 PBC, and 118 PSC), with detailed demographic, clinical, and lab characteristics in Table 1. A higher proportion of females was noted across all groups, particularly in PBC (85.3 %). While AIH and PBC exhibited comparable mean ages (52.1 and 54.7 years, respectively), PSC patients were notably younger, with a mean age of 43.9 years. Whites were more prevalent in the PBC group, whereas Hispanics were more common in the AIH group. BMI (kg/m²) was slightly lower in PSC. In laboratory findings, AIH showed higher mean levels of transaminases ALT (70.5 U/L) and AST (59 U/L), and IgG values (1498.5 mg/dL). Conversely, ALP levels were elevated in PBC and PSC (165.5 U/L and 160.5 U/L, respectively). Cirrhosis, as defined based off of liver biopsy or fibroscan score (using a cutoff of ≥16 kPa), was present in 26.1 % of AIH patients, significantly more than in their AILD counterparts, with mean liver stiffness measured by FibroScan (kPa) also elevated in AIH compared to PBC and PSC (9.8, 8.4, and 9.2 kPa, respectively).

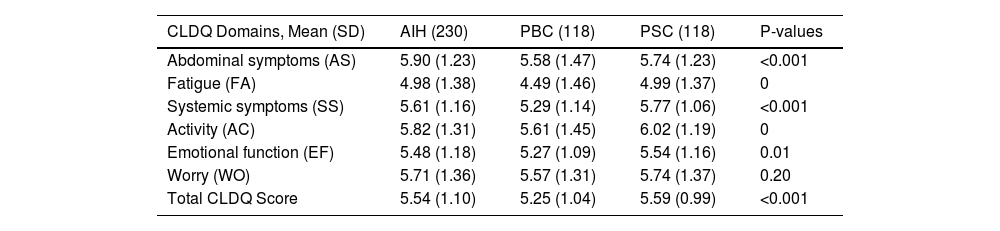

3.2Health-related quality of life in autoimmune liver diseaseIn Table 2, the domains compositing the full CDLQ are summarized. The total CLDQ mean for PBC was the lowest at 5.25 ± 1.04, while the total CLDQ means for AIH and PSC were comparable at 5.54 ± 1.04 and 5.59 ± 0.99, respectively. Upon analyzing the individual CLDQ domains (Table 2), fatigue (FA) is the domain with the lowestmean across the groups at 4.49 ± 1.46 for PBC compared to AIH and PSC with means of 4.98 ± 1.38 and 4.99 ± 1.37, respectively. Conversely, the domains worry (WO) and abdominal symptoms (AS) showcase the highest total mean average across the groups, with PBC again having the lowest scores, particularly in the AS domain with an average of 5.58 ± 1.47 compared to 5.90 ± 1.23 for AIH and 5.74 ± 1.23 for PSC. Although the WO domain does not reveal significant differences, the activity (AC) and emotional function (EF) domains exhibit statistically significant detrimental disparities for PBC in comparison to AIH and PSC. Specifically, PBC presents mean scores of 5.61 ± 1.45 for AC and 5.27 ± 1.09 for EF. Pearson's correlation showed that CLDQ and EQ-5D in AILD were strongly correlated (r = 0.63; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Figure 1).

CLDQ Scores comparing the means of each domain across the groups.

CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis; PBC: Primary Biliary Cholangits; PSC: Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; AS: Abdominal Symptoms; FA: Fatigue; SS: Systemic Symptoms; AC: Activity; EF: Emotional Function; WO: Worry; SD: Standard Deviation.

A detailed description of the components of each CLDQ domain can be found in Supplementary Table 1, in which PBC scored significantly worse in 20 out of the 29 questions on the CLDQ questionnaire. Tiredness, decreased energy, and sleepiness during the day were the most prominent symptoms, with scores of 3.91, 4.27, and 4.20 respectively (P < 0.001 each). Notably, every symptom reported as the worst fell within the FA domain. Decreased strength 5.21 and drowsiness 4.88 were also significantly lower in the PBC cohort compared to AIH and PSC.

In the AS domain (Supplementary Table 1), reported symptoms were significant only for abdominal bloating and abdominal discomfort, with AIH scoring the highest (5.23 and 5.93, respectively), and PBC being the most problematic (5.23 and 5.66, respectively). No differences in abdominal pain were found within this domain (P > 0.10). In the SS domain (Supplementary Table 1), PBC had the highest scores across all symptoms evaluated, with dry mouth (4.53) and bodily pain (4.94) being the most reported. Conversely, PSC reported the least symptoms within the SS domain, with high scores for shortness of breath (6.30) and muscle cramps (5.91).

In the AC domain (Supplementary Table 1), PBC reported significantly more trouble carrying heavy objects (5.22) and were also the most affected by diet restrictions (5.86). In the EF domain (Supplementary Table 1), which evaluated the highest number of symptoms, PBC scored significantly worse on 5 out of 8 of them. Among the symptoms with significant differences, concentration problems (5.03) and irritability (5.29) were the most reported by PBC. Difficulty falling asleep, though not statistically significant, was the most reported symptom among AIH, PBC, and PSC, with scores of 4.68, 5.16, and 4.88, respectively.

The components of the WO domain (Supplementary Table 1) showed fewer differences in our analysis (see Supplementary Table 1), with only 2 out of 5 questions showing significant differences. Specifically, worries about worsening of the condition and concerns about never feeling better were the only significant differences, resulting in PBC being the most affected AILD (5.21 and 5.51, respectively).

When analyzing the EQ-5D-5 L questionnaire (Table 3), we found that, similar to the CLDQ, PBC scored much lower in 4 out of the 6 UI items. Pain was the most debilitating symptom, with 41.1 % of PBC patients reporting "moderate to extreme pain and discomfort" and with UI mean of 1.45. Mobility item had the same means and CI in AIH and PBC 1.20, while PSC scored significantly better 1.10 (P < 0.001). The self-care item followed a similar trend, with AIH and PBC having similar mean UI scores 1.05 vs 1.06; respectively. Items such as performing usual activities or having anxiety or depression were not significant among the groups (P > 0.05). The overall VAS was also lower for patients with PBC 72.26 and highest for patients with AIH 77.28. The total mean UI score was the lowest for PBC 0.85 and same for AIH 0.88 and PSC 0.88.

ED-5Q-5 L scores comparing autoimmune liver disease group.

AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis; PBC: Primary Biliary Cholagitis; PSC: Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; EQ-5D-5L: EuroQol-5 Dimensions 5-Level; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; SD: Standard Deviation.

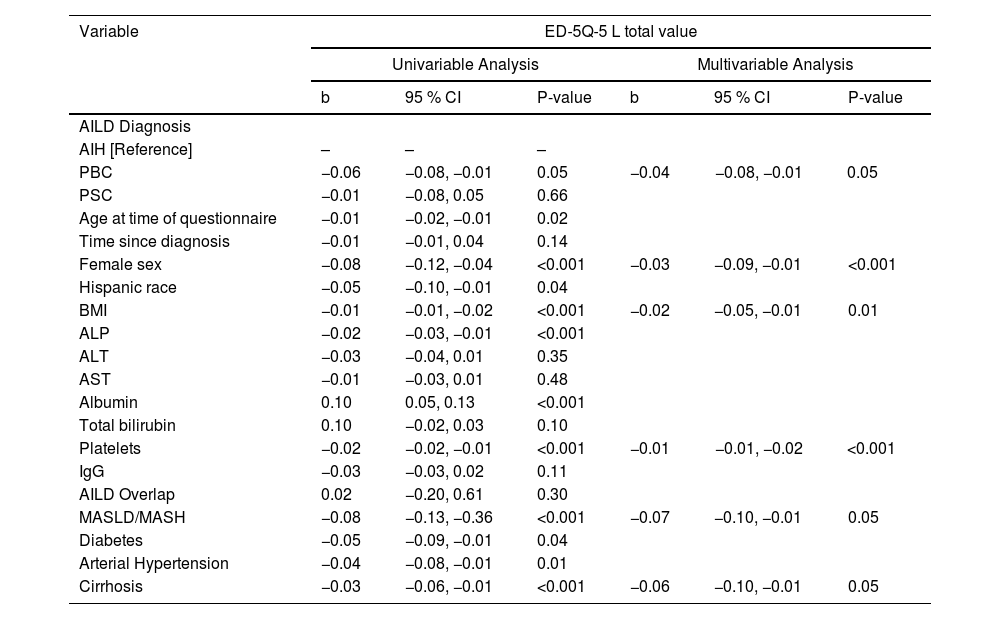

In a univariable analysis (Table 4), female sex (β: −0.32, P < 0.001) and Hispanics (β: −0.42, P < 0.001) were the demographic factors associated with an impaired HRQOL in AILD. Body mass index (BMI) (β: −0.03, P < 0.001) was also significantly associated with worse HRQOL. Blood markers such as ALP (β: −0.01, P < 0.001), ALT (β: −0.01, P + 0.02), AST (β: −0.02, P = 0.006) were also significantly associated with worse HRQOL, while albumin (β: 0.46, P < 0.001) was a predictor for better HRQOL. Comorbidities such as Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) (β: −0.33, P < 0.001), diabetes (β: −0.29, P = 0.002), and cirrhosis (β: −0.24, P < 0.001) were also significantly associated with worse HRQOL.

Univariate and Multivariate predictors of health-related quality of life indicators in autoimmune liver disease considering the CLDQ questionnaire.

CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; BMI: Body Mass Index; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; AILD: Autoimmune Liver Disease; MASLD: Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease; MASH: Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis; CI: Confidence Interval; b: Beta Coefficient.

In the multivariate analysis (Table 5), female sex (β: −0.26, P = 0.003) and Hispanics (β: −0.31, P = 0.01) had strong predictive association with an impaired HRQOL in AILD. BMI (β: −0.01, P = 0.01) was also significantly associated with worse HRQOL, although in a lesser extent. ALP was the only liver function related blood marker associated with worsening HRQOL in AILD (β: −0.01, P < 0.001). Comorbidities such as MASLD/MASH (β: −0.32, P = 0.01) and cirrhosis (β: −0.26, P = 0.04) were also significantly associated with worse HRQOL.

Univariate and Multivariate predictors of health-related quality of life indicators in autoimmune liver disease considering the EQ-5D-5 L questionnaire.

EQ-5D-5L: EuroQol-5 Dimensions 5-Level; BMI: Body Mass Index; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; AILD: Autoimmune Liver Disease; MASLD: Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease; MASH: Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis; CI: Confidence Interval; b: Beta Coefficient.

In this prospective, seven-year single-center cohort study, we assessed HRQOL in the three most common AILD in the U.S., using the validated CLDQ and EQ-5D-5 L questionnaires. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind, identifying key factors impacting HRQOL across all AILDs, with subgroup analysis highlighting several notable findings.

The PSC group appeared to carry the lowest symptomatic burden with regards to HRQOL, with a mean CLDQ score of 5.59, the highest of the three AILD groups. PSC patients scored highest among the AILDs in the AC, WO, and AS parameters. This aligns with a previous finding by Benito de Valle et al., who demonstrated using the SF-36 questionnaire assessment tool patients with PSC scored nearly the same as the general population in the fatigue parameters [17]. Notably, the PSC cohort was on average the youngest of the three AILDs, with an average age of 43.9.

Interestingly, PBC patients had the most significantly impacted HRQOL among those with AILDs, with a CLDQ score of 5.25 and an EQ-5D-5 L score of 0.85, both lower than AIH and PSC groups. This is noteworthy, particularly considering that PBC has the widest range of disease-modifying therapies available for treatment in comparison to PSC and AIH, and historically has been thought to portend to a favorable prognosis when managed appropriately.

Fatigue seemingly was a principal factor in the poor HRQOL amongst the PBC group, with the lowest CLDQ domain score of 4.49. According to multiple studies, severe fatigue, affecting one in five PBC patients, is the most debilitating and hardest to control symptom [2]. FDA-approved treatments like ursodeoxycholic acid and obeticholic acid have not improved fatigue [18–20], and liver transplantation has likewise not reliably resolved fatigue [21–24]. As of August 2024, newly FDA approved PPAR agonists have shown favorable effects on pruritus and early signals of benefit for fatigue. This was further evaluated by a recent phase 3 trial of elafibranor that demonstrated significant biochemical improvements in markers like ALP [25], and emerging post-hoc analyses that suggest potential improvements in fatigue that were not captured in the primary trial report [26].

Another PPAR agonist, seladelpar, has shown promise, significantly improving PBC-associated fatigue and pruritus, with benefits lasting up to a year after treatment initiation [27]. Phase 2 and 3 studies reported substantial reductions in pruritus and improvements in fatigue using the PBC-40 questionnaire, with pruritus numerical rating scale (NRS) reductions of −3.2 compared to −1.7 for placebo [27,28]. Beyond fatigue, our analysis further noted that PBC patients trended towards more disabling abdominal symptoms, worsened activity levels, larger impact of worry, and poorer emotional function in comparison to PSC and AIH patients.

In addition to poorly controlled symptoms driving the PBC group’s lowest HRQOL, further contributions could be due to the group’s demographics. The PBC group was the oldest cohort with the highest BMIs and had the largest majority of females in comparison to the AIH and PSC groups. Overall, further research is needed to explore effective treatments for the symptomatic impact and impaired HRQOL for PBC patients. Our MVA identified female sex as a strong predictor of higher symptom burden in AILD (OR −0.26), possibly due to stronger immune responses to self-antigens [29]. Other risk factors for impaired HRQOL included elevated liver enzymes, concomitant MASLD, female sex, and Hispanic race.

Among all factors assessed, concomitant MASLD emerged as the strongest independent predictor of reduced HRQOL across both CLDQ and EQ-5D-5 L instruments, associated with a 32 % and 7 % increased likelihood of worse scores, respectively. Although studies specifically addressing MASLD in AILD are lacking, Czapla et al. demonstrated significantly higher rates of physical discomfort (48 % vs. 30 %), impaired daily activities (54 % vs. 29 %), and attention difficulties (57 % vs. 32 %) in patients with MASH, findings closely aligned with ours [30]. The second strongest predictor was Hispanic race, potentially linked to previously documented higher rates of severe liver complications (e.g., ascites, variceal bleeding) [31], and genetic predisposition through variants like PNPLA3, which increase susceptibility to hepatic steatosis and advanced liver disease [32].

The psychological impact of AILDs is a key focus of our study. While no significant differences were found in worry (CLDQ) or anxiety and depression (EQ-5D-5 L) across AILDs, emotional function was notably worse in PBC compared to other diseases. All AILD patients reported being affected by worry. The questions in the emotional function domain are similar to those in depression questionnaires such as the PHQ-9. Over the last several years, there has been controversy and discrepancies regarding which AILD group is most impacted on a psychological level by their disease [33–35] or whether external factors might contribute [36]. Al-Harthy et al. reported a 12 % prevalence of depression among PBC patients [33], while Shaheen et al. reported a lower rate of 7.3 % (95 % CI 0–15 %) [37]. In other studies, now including AIH, such as Schramm et al., the frequency of depressive syndrome was more than twice as high as in the general population (5.9 % vs. 2.6 %) with an overall prevalence of 10 % [4]. Other studies, such as Nayagam et al., now focusing on PSC patients, have found an even greater psychological impact, reporting PHQ-9 scores ≥10 in 11 out of 52 patients (21.1 %) and GAD-7 scores ≥10 in 5 out of 52 patients (9.6 %) [38]. These findings suggest a strong presence of major depressive disorder and anxiety in AILDs.

Our study, the first to compare PSC, AIH, and PBC, suggests that PBC is most affected. These findings suggest current screening methods may underestimate emotional impairment and psychiatric disorders in AILDs, explaining literature discrepancies ranging from 5.5 % to 29 %, depending on the cohort [7].

Fatigue, the most pressing and frequently reported symptom in AILD, has been the focus of significant recent advances. For example, the ELMWOOD trial by Levy et al. in PSC patients showed reduced fatigue with elafibranor, reported in 13.0 % of placebo patients vs. 4.5 % (80 mg) and 4.3 % (120 mg); similar improvements were seen in pruritus and nausea [39]. Similarly, in PBC patients, according to Jones et al. Elafibranor improves fatigue, with 66.7 % achieving a ≥ 3-point improvement in the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Fatigue Short Form 7a and a 9.5 % mean score reduction by week 52, compared to 31.3 % and 4.2 % with placebo [40], supporting the findings of the ELATIVE trial [26]. Although already being actively addressed in recent studies [25,26,28,40], our findings help strengthen the evidence base, underscoring the importance of continued therapy development for PBC patients—particularly after August 2024 in which recently FDA approved PPAR agonists have shown favorable effects in pruritus and promising results with fatigue.

Our study has several limitations. First, as this study was conducted at a single center in the northeast U.S., the findings may not be generalizable to all AILD populations. Second, while the cohort was sizeable (n = 466), we could not compare some clinically relevant predictors of HRQOL due missing data. That includes socioeconomic status, age group categorization, and other liver-related major adverse events. Third, excluding patients with expected life expectancy of less than six months is standard, but it might help to discuss the potential impact of this exclusion on HRQOL outcomes, especially if the more severe stages of AILDs are underrepresented. Fourth, concomitant diseases such as hypothyroidism and IBD might have impact in the fatigue burden of AILD patients, which can be worth to separately study. This HRQOL assessment may enhance current clinical models for predicting hospitalizations and mortality. Future studies with larger samples could further investigate modifiable factors affecting HRQOL across different AILDs.

5ConclusionsWhile the medical management of AILD varies in each subtype and is often the primary concern of clinicians, assessing the HRQOL of these patients is critical – and understanding which subtypes may be more prone to certain symptoms is crucial. We conclude that PBC appears to be the most impacted AILD with regards to HRQOL, with debilitating symptoms including fatigue, sleepiness, concentration deficits, worry, and pain. The AIH subgroup also showed several predictors for worse HRQOL, including female sex predictors, Hispanic ethnicity, MASLD/MASH overlap, and advanced cirrhosis. We recommend routine mental health evaluations, such as depression or anxiety screening (PHQ-9 or GAD-7) for general practice in AILD patients, especially after diagnosis of PBC. While emerging PPAR agonists promising, our study emphasizes the urgent need for research on treatments targeting PBC-related fatigue as well as broader AILD HRQOL symptomatology.

Author contributionsL.S.: conceptualization, project administration, data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, visualization, writing the original draft, review, and editing;B.F.: writing the original draft, review, and editing; A.M.-F.: conceptualization, visualization, writing the original draft, writing the review, and editing; M.A.: data curation, project administration, writing the original draft, review, and editing; N.R.: conceptualization, visualization, data curation, and editing; R.B.: data curation; D.G.: data curation; E.M.-M.: data curation and writing the original draft; B.S.: formal analysis, and resources; V.P.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, and visualization; A.B.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing the original draft, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The previous is attached in a separate document.

The data used in this study are from a single center and are available for other institutions upon request. Access to de-identified data can be provided following a pre-approved transfer by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Institutional Review Board (IRB).