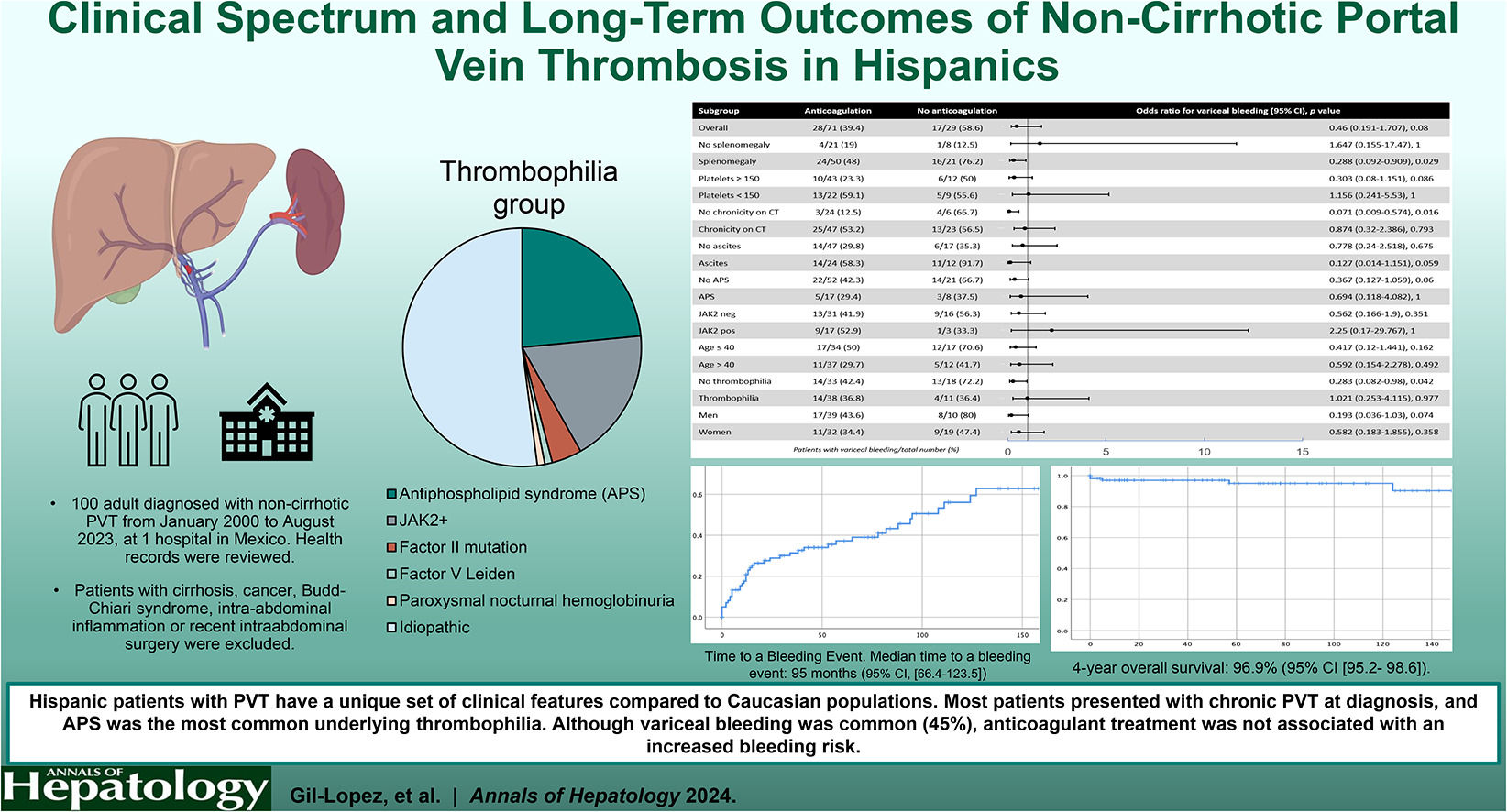

Visual abstract

Portal venous system thrombosis (PVT) encompasses the obstruction of the portal vein, with or without extension to other segments of the splanchnic venous system (splenic vein or superior mesenteric vein). Classically, it was categorized as acute or chronic based on clinical and imaging criteria [1], and more recently it has been proposed to categorize it as recent (<6 months) or chronic (>6 months), based on imaging findings and assumed time course [2]. This condition is relatively uncommon, with an estimated incidence of 0.7 per 100,000 person-years reported in the general population [3].

Among individuals without cirrhosis, an underlying risk factor for PVT is identified in approximately 70 %. European multi-center studies have reported thrombophilia in 42–50 % of patients, with a local risk factor identified in 15–21 % [4–6]. Commonly associated risk factors for PVT include myeloproliferative neoplasms, the JAK2 V617F mutation, cancer, inherited thrombophilia (such as Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency) and acquired thrombophilia (such as antiphospholipid syndrome APS, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria [PNH]), systemic prothrombotic conditions (including autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, hormonal supplementation), and intra-abdominal inflammation [1,3,4]. The utility of thrombophilia testing in patients lacking an identifiable predisposing factor has been a matter of controversy, with scant evidence supporting the recommendations put forth by various organizations [7,8].

Nevertheless, the existing literature primarily comprises data from the Caucasian population, with little information on the clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes in other racial and ethnic groups. Notably, sociodemographic factors and healthcare access in Hispanic populations markedly differ from those in Western Europe, potentially influencing the clinical presentation of PVT patients [9,10]. Furthermore, the thrombophilia profile of Hispanic populations with unprovoked venous thrombosis differs, with Factor V Leiden, APS and JAK2 mutation comprising a small proportion of cases (∼10 % altogether) [11,12]. Thus, our study aims to elucidate the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, etiological factors, and relevant outcomes among Hispanic adults with non-cirrhotic PVT unrelated to intraabdominal inflammatory conditions.

2Patients and MethodsThis is a retrospective cohort study reporting the experience of a single tertiary care hospital in Mexico City (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán [INCMNSZ]) that included adult patients diagnosed with PVT from January 2000 to August 2023.

Health records were reviewed to obtain demographics, past medical history, clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, and imaging results. In order to identify patients with primary etiologies and reduce heterogeneity amongst the cohort, patients with a documented diagnosis of cirrhosis, cancer, Budd-Chiari syndrome, intra-abdominal inflammatory processes (abdominal sepsis, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease) or intraabdominal surgery within the preceding year were excluded given the well-established increased risk of PVT in these settings. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was excluded based on a comprehensive evaluation, integrating patient's history, clinical manifestations (cirrhosis stigmata, spider angiomas, jaundice), laboratory assessments (abnormal liver function tests), and abdominal imaging findings, as documented in the health record of each patient. A flowchart depicting the study population is found in Fig. 1.

Thrombophilia testing was customized based on each patient's individual circumstances, including their history of previous thrombosis, abnormal blood cell counts, and organomegaly. The testing was also aligned with available resources and expert consultant opinion to optimize diagnostic efficiency for the specific clinical scenario, which precluded standardized thrombophilia testing in all patients and, therefore, potentially selective testing in some patients. Patients were classified into groups: those with thrombophilia-associated PVT, characterized by the presence of one or more thrombophilia factors as follows: APS, as defined by the 2006 revised Sapporo classification criteria [13], JAK2 mutation, Factor II G20210A mutation, Factor V Leiden mutation, or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Otherwise, they were classified as idiopathic PVT, based on laboratory results of the following thrombophilia tests: antiphospholipid syndrome (Anti-Beta 2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies IgG and IgM [anti-B2GPI], anticardiolipin antibodies IgG and IgM [aCL]), JAK2 V617F mutation, and PNH testing, which are unaffected by anticoagulant treatment (some patients were receiving it at the time of diagnosis) or acute-phase inflammation [7,14]. Thrombophilia tests were conducted using standard institutional procedures, including Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Anti-B2GPI and aCL [15]. Polymerase chain reaction for JAK2V617F mutation analysis was performed with a probe from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) with LightCycler 2.0 Thermocycler. PNH was diagnosed by flow cytometry measuring CD14, CD15, CD24, CD45, CD59, CD64, CD235, and FLAER (BD Canto II Becton, Dickinson and Company, San Jose, California, USA), according to international laboratory standards [16]. Factor II G20210A mutation and Factor V Leiden mutation were identified through a positive polymerase chain reaction assay according to international laboratory standards. A diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasm was considered if the patient met the World Health Organization criteria at the time of diagnosis [17], as documented in the patient's health record. Due to the potential interference from concurrent anticoagulant treatment at the time of diagnosis, a single positive lupus anticoagulant test was not considered diagnostic of APS, and other thrombophilia tests including protein C and S deficiency and antithrombin III deficiency, were excluded from this analysis. Therefore, the cohort was classified as previously stated [18] with regards to thrombophilia status. Given the different clinical course of recent and chronic PVT group, we also performed a comparison between these 2 groups. This classification was based on imaging findings, with chronic PVT defined by the presence of chronic thrombi features in the portal vein or collateral vessels [1,19], according to institutional radiology reports. If none of these features were reported on imaging and/or if the mentioned radiology reported acute PVT feature, patients were classified as recent PVT.

Clinical variables and outcomes relevant to PVT were compared between the thrombophilia and idiopathic groups, as well as between the recent and chronic PVT groups. Comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic kidney disease) were defined according to the patient's health records. The time of diagnosis was considered delineated as the moment of the initial institutional imaging study conducted to investigate suspected PVT. Previous venous thrombosis was defined as any venous thrombotic event diagnosed prior to PVT as specified in the health record. Splenomegaly was defined as a spleen length >12 cm in imaging studies, as specified in the official radiology report [20]. PVT extension was classified as porto-mesenteric, porto-splenic and portal based in computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound (US) institutional reports. Varices at diagnosis referred to the presence of esophageal varices identified during upper endoscopy performed before or at the time of PVT diagnosis. VB was defined as any upper gastrointestinal bleeding event of variceal origin confirmed by endoscopy prior to diagnosis or during follow-up. Anticoagulant treatment exceeding >12 months was accounted for if the patient received any kind of anticoagulant treatment consistently for that period during follow-up. Major bleeding was defined according to the most recent International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis definition [21]. Recanalization denoted the restoration of portal vein system (PVS) patency as observed through CT, MRI, or US during follow-up. PVT rethrombosis referred to a new event of PVT documented during follow-up. De-novo thrombosis event encompassed any new arterial or venous thrombotic event occurring during follow-up. New-onset esophageal varices development was defined as the new appearance of esophageal varices on endoscopy during follow-up. Ascites was considered positive if present on imaging studies at the time of diagnosis or during follow-up. Encephalopathy was defined according to West-Haven scale [22], as documented on health records during follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the length of time measured in months from diagnosis to death resulting from any cause. Time to bleeding event was defined as the length of time measured in months from diagnosis to the occurrence of a bleeding event. Cavernomatous degeneration was defined as the presence of cavernoma features on imaging at the last follow-up as documented in the patient's health records.

Primary outcomes were OS and VB according to the presence or absence of thrombophilia. Secondary outcomes included major bleeding, recanalization, portal venous system (PVS) rethrombosis, de-novo thrombosis, new-onset esophageal varices development, cavernomatous degeneration at last follow-up, ascites, encephalopathy, time to bleeding event, and effect of the anticoagulation on variceal bleeding in the whole cohort and across different subgroups.

2.1StatisticsBaseline characteristics were summarized as medians with ranges and percentages or means with standard deviations according to data distribution for descriptive purposes. Differences between categorical variables were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Differences between medians were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Risk factors were assessed by calculating odds ratio (OR) along with 95 % confidence interval (CI). A multivariate analysis with a logistic regression model was performed including the variables that were clinically and/or statistically significant. Time-to-event variables were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons among the prognostic subgroups were analyzed using the log-rank test. A subgroup comparison was performed between the most prevalent thrombophilias (JAK2 mutation and APS). Moreover, a multivariate analysis was performed to assess the risk factors of bleeding due to variceal bleeding. Statistical significance was determined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software, Version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the statistical tests employed and the rationale for each.

2.2Ethical statementWritten informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the present study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in the approval by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (Approval Number/ID: HEM-5028–24–24–1).

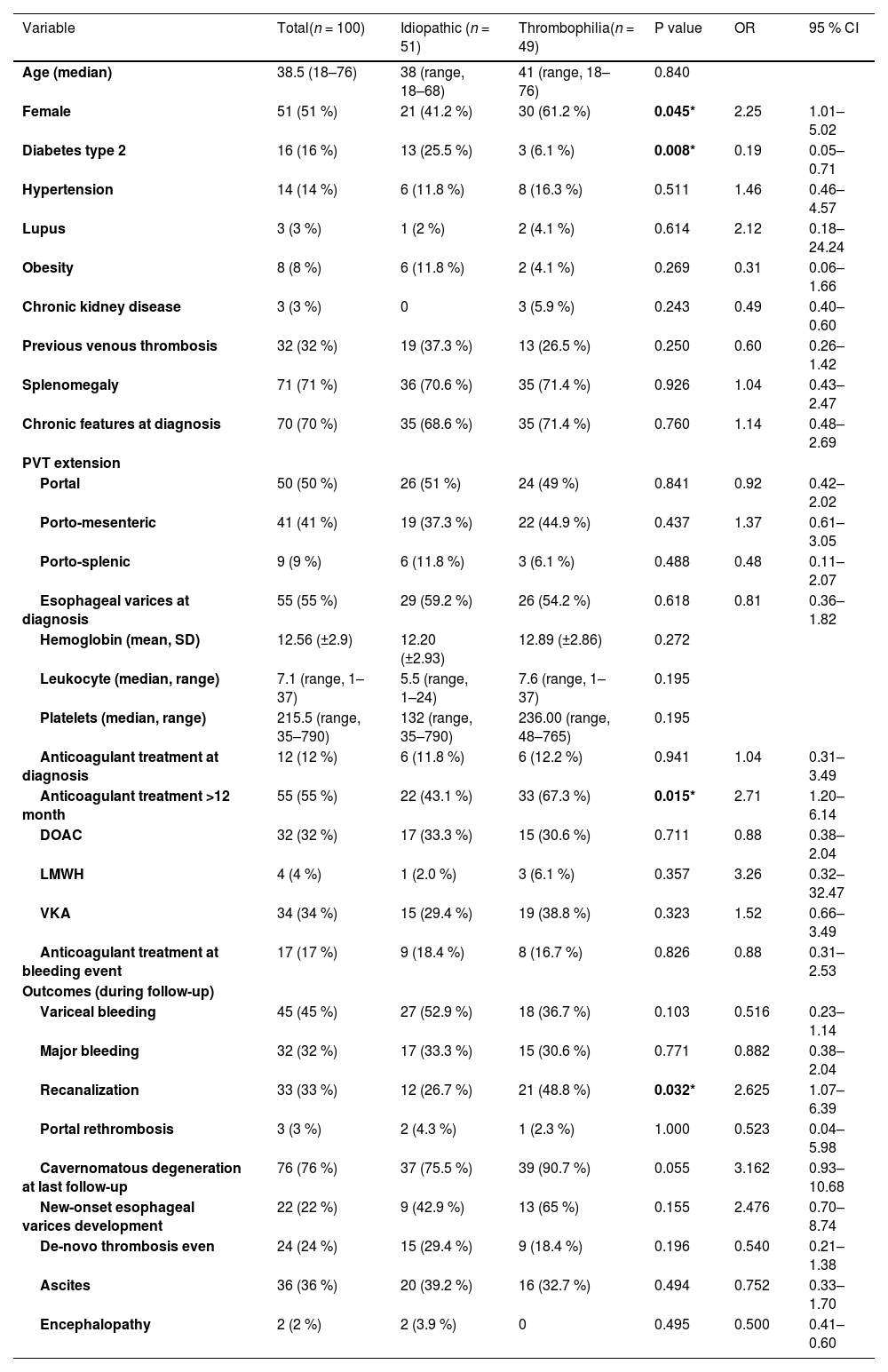

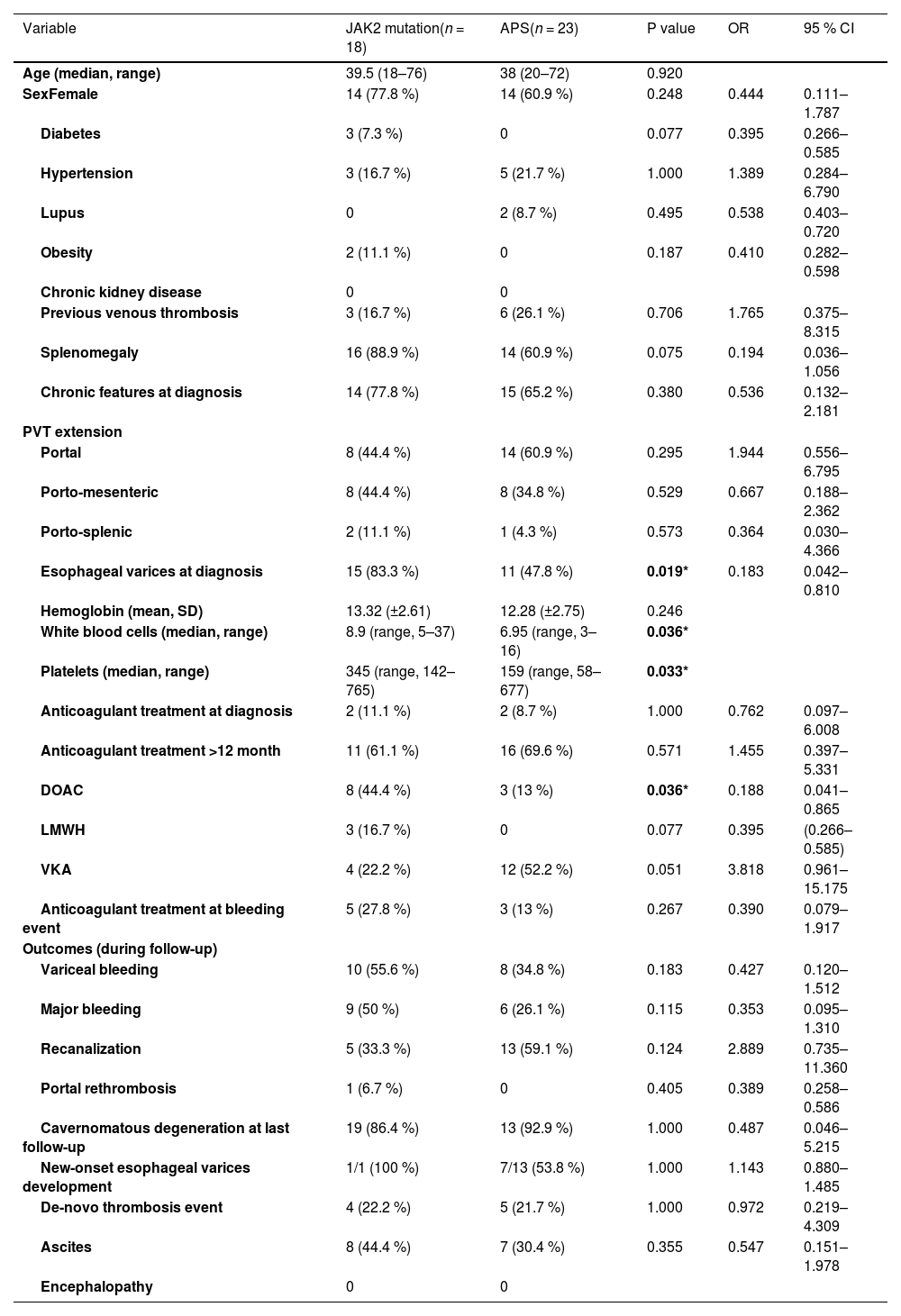

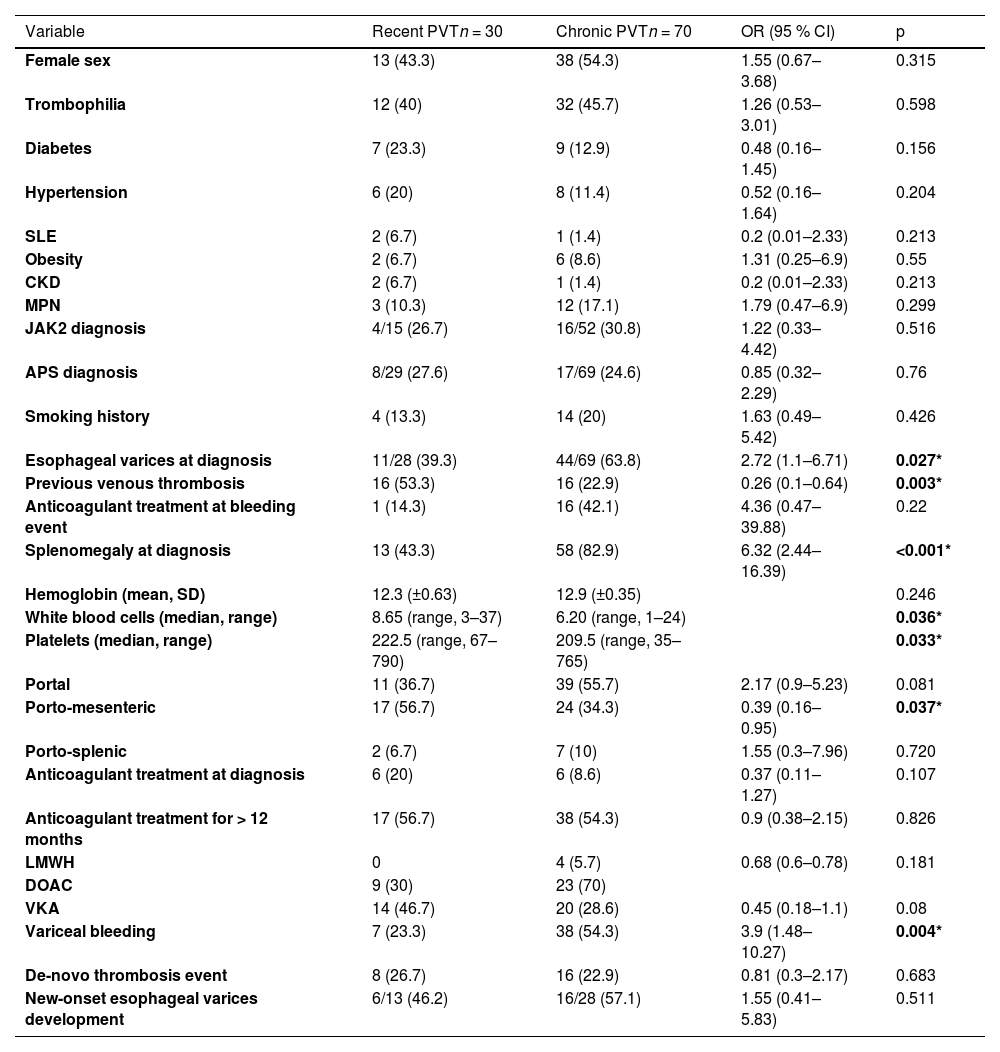

3Results3.1General cohort characteristicsFrom 2000 to 2023, 100 consecutive individuals were included in the study. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics, baseline clinical characteristics, treatment received, and relevant clinical outcomes during follow-up. Table 2 encompasses the comparison between patients with recent vs. chronic PVT.Table 3 comprises solely the APS and JAK2 mutation groups, representing the most prevalent thrombophilias.

Baseline characteristics and relevant clinical outcomes during follow-up.

There was a statistically significant difference (*) for female sex, diabetes type 2, anticoagulant treatment >12 months, and recanalization between the thrombophilia and idiopathic group.

Baseline characteristics and relevant clinical outcomes during follow-up (JAK2 mutation and APS). The 2 patients with both diagnoses were excluded.

There was a statistically significant difference for esophageal varices at diagnosis, white blood cell and platelets counts and the use of DOAC between the JAK2 mutation and APS groups.

Baseline characteristics and relevant clinical outcomes during follow-up of patients with recent vs. chronic PVT.

There was a statistically significant difference for esophageal varices at diagnosis, previous venous thrombosis, splenomegaly at diagnosis, white blood cells, platelets and the frequency of porto-mesenteric extension of the PVT between the recent and chronic PVT groups.

The median age at diagnosis was 38.5 years (range 18–76), with females constituting 51 % of the cohort. Prevalent comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (16 %), arterial hypertension (14 %), obesity (8 %) and lupus (3 %). Additionally, 15 patients had a confirmed diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasm (15 %).

Among the cohort, 49 % had a thrombophilia diagnosis, encompassing 23 cases of APS, 18 of JAK2 mutation, 4 cases of Factor II G20210A mutation, one case of Factor V Leiden, one case of PNH and two patients with APS and JAK2 mutation simultaneously.

As part of the thrombophilia work-up, 6 patients were considered to have Protein C deficiency (3 of them positive for APS), 10 patients were considered to have Protein S deficiency (one positive for APS and JAK2 mutation, two positive for JAK2 mutation only, one positive for APS only). Since the patients were concurrently taking vitamin K antagonist (VKA) at the moment of laboratory testing, the cases were reviewed by a thrombosis expert (AVR) and it was concluded that the diagnosis of thrombophilia was uncertain; therefore, patients were included in the idiopathic group.

Furthermore, imaging revealed chronic PVT in 70 % of cases. In terms of extension, PVT was limited to the portal vein (PV) in 50 % of cases, followed by porto-mesenteric (41 %) and porto-splenic (9 %). At diagnosis, 55 % had esophageal varices. Mean hemoglobin value was 12.56 g/dL (±2.9), median leukocyte count was 7.1 × 10^3 cells/uL (range, 1–37), and median platelet count was 215.5 × 10^3 cells/uL (range, 35–790).

3.2Thrombophilia vs. idiopathicThrombophilia was significantly associated with female sex (61.2 % thrombophilia vs 41.2 % idiopathic, OR 2.25, 95 % CI [1.01–5.02], p = 0.045) and prolonged anticoagulation use (>12 months) (67.3 % thrombophilia vs 43.1 % idiopathic, OR 2.71, 95 % CI [1.20–6.14], p = 0.015). Conversely, type 2 diabetes was more prevalent at diagnosis in the idiopathic group (25.5 % idiopathic vs 6.1 % thrombophilia, OR 0.19, 95 % CI [0.05–0.71], p = 0.008). The rest of the baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of both groups are depicted in Table 1.

3.3Recent vs chronic PVTEsophageal varices at diagnosis (63.8 % vs. 39.3 %, OR 2.72, 95 % CI [1.1–6.71], p = 0.02), as well as splenomegaly at diagnosis (82.9 % vs. 43.3 %, OR 0.26, 95 % CI [0.1–0.64], p = 0.003), variceal bleeding (54.3 % vs. 23.3 %, OR 3.9, 95 % CI [1.4–10.2], p = 0.004), and major bleeding (40 % vs. 13.3 %, OR 4.3, 95 % CI [1.3–13.7], p = 0.009) were significantly more frequent in the chronic PVT group. Previous venous thrombosis was more frequent in the recent PVT group compared to the chronic PVT group, with a statistically significant difference (53.3 % vs. 22.9 %, OR 0.26, 95 % CI [0.1–0.6], p = 0.003). The rest of the baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of both groups are depicted in Table 3.

3.4APS vs JAK2 mutation patientsComparing patients with JAK2 mutation with APS patients, esophageal varices at diagnosis were more frequent in JAK2 mutation patients (83.3 % JAK2 mutation vs 47.8 % APS, OR 0.18, 95 % CI [0.04–0.81], p = 0.019). There were no other statistically significant differences between groups. The rest of the baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of both groups during follow-up are depicted in Table 2.

3.5Clinical outcomes and survivalThe median follow-up among surviving patients was 55 months (range, 0–321, IQR 15–102.5). Anticoagulant treatment was consistently administered for >12 months to 55 patients, predominantly utilizing VKA (34 %) and DOAC (32 %). The incidence rate of a new thrombotic event was 42.7 per 1000 person-year, with a five-year risk of re-thrombosis of 24 %. On the other hand, the incidence rate of developing VB was 80.2 per 1000 person-year, with a five-year risk of VB of 45 %, 71.1 % being major bleeding events. Furthermore, imaging revealed recanalization in 33 patients and a five-year risk of cavernomatous degeneration of 76 % (41 in the idiopathic group, 35 in the thrombophilia group).

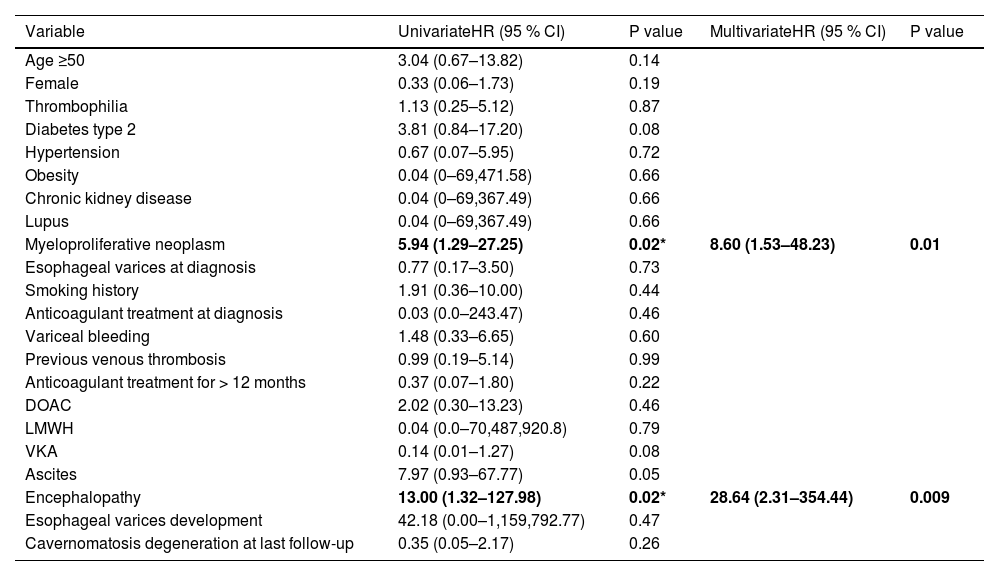

The median time to a bleeding event was 95 months (95 % CI, 66.4–123.5) (Fig. 3). The 4-year OS was 97 %, with seven patient deaths recorded during follow-up (Fig. 4). Four patients had JAK2 mutation and 3 belonged to the idiopathic PVT group. One patient died of non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding at 157 months of follow-up, one due to acute bleeding after a biopsy procedure at 156 months, one due to acute cholangitis at 124 months, one due to acute bleeding after thrombolysis at PVT diagnosis, one due to acute coronary syndrome at 5 months, one due to acute VB at diagnosis and one due to pneumonia at 57 months of follow-up. Comparing the recent PVT group vs. chronic PVT group, 4-year OS was 100 % for the chronic PVT group, and 89.7 % for the recent PVT group. Four-year median OS was not reached and it was not different between groups (Log-rank test: χ2 1.578, p = 0.209), with an HR for mortality of 0.39 (95 % CI 0.08–1.78, p = 0.225) for having a thrombophilia diagnosis. The only variables independently associated with mortality in a multivariate analysis were having a diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasm (HR 8.6, 95 % CI [1.53–48.23], p = 0.014) and encephalopathy (HR 28.64, 95 % CI [2.31–354.44, p = 0.009]) (Table 5).

Regarding VB, major bleeding, PVT rethrombosis, cavernomatous degeneration, new-onset esophageal varices development, ascites, and encephalopathy, there were no statistically significant differences between the thrombophilia and idiopathic group (Table 1), nor between the JAK2 mutation and APS subgroups (Table 2). Nevertheless, recanalization was more common in the thrombophilia group (48.8 % thrombophilia vs 26.7 % idiopathic, OR 2.62, 95 % CI [1.07–6.39], p = 0.03).

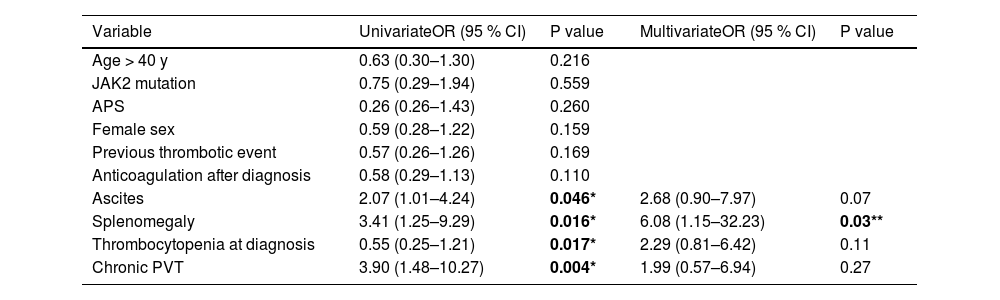

We performed univariate and a multivariate analyses to assess the risk of VB. Only the presence of splenomegaly at diagnosis was significantly associated with VB (OR 6.08, 95 % CI [1.15–32.23], p = 0.03) (Table 4). Overall, anticoagulant treatment was not associated with an increased risk of bleeding (OR 0.46, 95 % CI [0.19–1.70], p = 0.08) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analyses of the effect of anticoagulation on variceal bleeding risk are shown in Fig. 2. Anticoagulant treatment was associated with a reduced risk of bleeding in patients with splenomegaly, no chronicity features on CT, and those with no thrombophilia.

Variables associated with variceal bleeding (univariate and multivariate analysis).

Univariate and multivariate analysis for variables associated with mortality.

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort study to report the clinical characteristics and outcomes of non-cirrhotic non-malignant PVT unrelated to intraabdominal inflammatory conditions in a Hispanic population. Prior research on this topic by Cruz-Ramon et al. [23] included 25 non-cirrhotic Mexican patients, of whom only 2 had a procoagulant disorder, 15 had other predisposing conditions, and 7 with no discernible risk factors.

Previous studies, predominantly from Western European populations, have reported an identifiable “thrombophilia” in around 60 % of patients [24]. However, the detection of major thrombophilia (APS, JAK2 mutation, PNH, homozygous prothrombin gene mutation and factor V Leiden) [6,25] has been notably lower, ranging from around 5–30 % [24,26,27]. Contrastingly, APS emerged as the most prevalent thrombophilia in our cohort, followed by JAK2 mutation. Remarkably, the prevalence of APS in our study markedly exceeded previously reported rates in European populations [3,4,28], possibly attributable to the study performed in a national referral center that concentrates a significant portion of the nation's APS and JAK2 mutation cases. Of note, diagnosis confirmation, adherent to current APS guidelines [13], was executed by an experienced rheumatologist and/or hematologist.

Interestingly, PVT as a manifestation of APS, although reported to be exceedingly rare (∼1 %) [29–32], warrants awareness as a major feature of this condition, suggesting the need for a reciprocal consideration of APS within the differential diagnosis of unprovoked PVT. However, it should be acknowledged that the thrombophilia detection rate may have been affected by the testing approach that was previously discussed, where, although most of them underwent an extensive workup, not all patients underwent the same laboratory tests, which could have led to a sub-diagnosis of some thrombophilia conditions, with potentially a lower idiopathic cases rate and, thus, differences in the subgroup analyses.

The median age at diagnosis aligns with recent reports, confirming young and middle-aged adults as the primarily affected demographic [27]. This holds particular significance in survival analysis, as the majority of PVT patients do not die due to this condition, but rather due to complications arising from portal hypertension [33].

At the time of presentation, the majority of patients displayed chronic PVT (70 %), a phenomenon that was potentially influenced by several factors: asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic initial PVT episodes [24,34], low clinical awareness among clinicians due to its infrequency, and limited effective access to healthcare in Mexico [10]. Consequently, acute PVT is probably unrecognized and, hence, probably underrepresented. We performed a comparison between the recent PVT vs. chronic PVT groups; the latter exhibited significantly higher rates of esophageal varices at diagnosis, splenomegaly at diagnosis, variceal bleeding, and major bleeding. Interestingly, the recent PVT group was significantly more prone to having a history of previous venous thrombotic event, which could probably reflect a higher propensity for thrombosis, but there were no differences in the thrombophilia status of both groups.

Only 55 patients received long-term anticoagulation (>12 months). This was most likely a multifactorial phenomenon: physician's concerns regarding bleeding risk, prior bleeding events, and the scarcity of evidence about the effectiveness of long-term anticoagulation in this population. Further efforts to promote anticoagulant treatment and medical follow-up should be pursued, given its demonstrated safety and efficacy in preventing many secondary complications [6,35,36]. Current consensus recommendations endorse indefinite anticoagulation consideration in unprovoked PVT patients, acknowledging that evidence supporting this statement is weak and, therefore, the necessity for individualized approaches [8,37]. However, long-term anticoagulant treatment (>3–6 months) specifically for chronic PVT in the absence of thrombophilia has classically been discouraged [5,38]. Most of the evidence regarding the treatment and prognosis of this population has been historically extrapolated from PVT in patients with cirrhosis [5], and prospective data regarding the optimal management outside the cirrhosis setting remains limited. Prospective data supporting anticoagulation for chronic unprovoked PVT in non-cirrhotic patients has been recently published, supporting the efficacy and safety of long-term anticoagulation for the prevention of rethrombosis, without increasing variceal bleeding risk in these patients, particularly chronic non-cirrhotic PVT, even when no major thrombophilia is documented [6].

Remarkably, in our study, the group with no chronicity on CT exhibited a lower incidence of VB with anticoagulant treatment, potentially attributable to lesser portal hypertension. Even though the study's primary objective was not to assess the bleeding risk, anticoagulant treatment did not increase this risk, which is consistent with previous reports where bleeding risk was uncommon in patients on anticoagulation [4,6]. Therefore, adherence to current treatment recommendations for Hispanic patients seems appropriate.

In contrast to the idiopathic group, the thrombophilia group did not appear to benefit from long-term anticoagulation (>12 months), possibly due to inherent difficulties associated with the use of VKA, the primary anticoagulant choice in APS. Some health-care barriers found in this setting such as the regular and close medical follow-up required for VKA management could potentially explain this finding. Furthermore, most JAK2 mutation patients fulfilled the criteria for a myeloproliferative neoplasm, potentially conferring an increased bleeding risk due to the associated acquired von Willebrand syndrome [39,40].

Despite these nuances, rates of VB, major bleeding, recanalization, PVS rethrombosis, cavernomatous degeneration, new-onset esophageal varices development, ascites, and encephalopathy did not significantly differ between thrombophilia and idiopathic group, or between the JAK2 mutation and APS subgroups. This raises the question of whether extensive thrombophilia testing is mandatory in all individuals [25,37], particularly since many of them are young patients with unprovoked venous thrombosis in an unusual site.

Certainly, establishing the diagnosis of PNH, APS and JAK2 mutation related disorders entails a different approach, since a positive result for APS would make VKA the only reasonable anticoagulant choice (given the unacceptable outcomes of DOAC in patients with APS [41–43]), underlying PNH would entail disease-specific treatment [44], and finding a JAK2 mutation makes it mandatory to search for a myeloproliferative neoplasm [26,45,46]. Therefore, in a resource-limited environment, selective thrombophilia testing focusing on PNH, APS, and JAK2 mutations may be prudent since these subgroups warrant specific therapeutic strategies. This affirmation is further supported by the high prevalence of APS and JAK2 mutation in this population, as shown in our results.

Finally, our study results align with a seminal study by Plessier et al. [6], where they found that rivaroxaban decreased the risk of recurrent thromboembolic events in patients with non-cirrhotic chronic PVT in the absence of major thrombophilia, without an increased risk of bleeding, as well as with the low mortality reported by other groups [36,47].

Interestingly, bleeding was never the cause of death in the few patients who died during follow-up in large European cohorts [4,35,36]. In contrast, our investigation revealed that three patients died due to bleeding-related complications (notably, only one death was directly linked to portal hypertension).

While this study presents valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge limitations such as its retrospective design and the single-center sampling method, which may introduce inherent biases and limit the generalizability of the results, especially for different healthcare systems and Hispanic populations. Nevertheless, this singular focus ensures the coherence and reliability of the data collected. Also, as we focused on primary PVT cases and therefore excluded secondary causes of PVT, this may limit the universality and broad applicability of our results given that PVT occurring in the context of cirrhosis, intraabdominal infection, or cancer, is far more common in the real-world setting.

5ConclusionsHispanic patients with non-cirrhotic PVT have a unique set of clinical features compared to Caucasian populations. APS emerged as the predominant underlying thrombophilia and, although this finding may be multifactorial in origin, our findings underscore the importance of considering APS as a potential non-cirrhotic PVT etiology. Other notable characteristics of this cohort include anticoagulant treatment's lack of increased bleeding risk conferred and its potential benefit in some subgroups, the predominance of chronic PVT features at diagnosis, and favorable survival outcomes during extensive follow-up periods. In comparison to the non-Hispanic population, Hispanics exhibit higher rates of esophageal varices and VB, emphasizing the imperative for ongoing vigilance in this population. Further prospective studies and uniform approaches should be encouraged to accomplish better outcomes.

None.

![Overall survival of the whole cohort. 4-year overall survival: 96.9 % (95 % CI [95.2- 98.6]). Overall survival of the whole cohort. 4-year overall survival: 96.9 % (95 % CI [95.2- 98.6]).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/16652681/0000003000000001/v1_202506020641/S1665268125000109/v1_202506020641/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)