Violence against women is one of the most widespread violations of human rights globally. In these cases, it is common to find injuries in the maxillofacial area, which can leave various types of sequelae.

ObjectiveTo characterize maxillofacial injuries from the examinations carried out under the Gender Protocol at the Valparaíso Legal Medical Service, Chile.

MethodologyA qualitative retrospective study was conducted using data collected from maxillofacial injury reports conducted between 2020 and 2023.

ResultsA total of 51 examinations were analyzed: the age of the victims ranged from 21–73 years, with the majority being homemakers and unmarried. In most cases, the aggressions were perpetrated by the women's current partners at their shared residence. In nearly a third of the cases, the aggression occurred in the presence of minors. The most commonly used injurious mechanisms were blunt and asphyxiation. There were injuries to soft tissues and hard tissues. The medicolegal prognosis in the majority of cases was less severe.

DiscussionThe evaluation of maxillofacial injuries by a dentist is fundamental, especially to assess intraoral injuries. Dentists should be familiar with forensic dentistry in these contexts, in order to accurately document injuries and contribute to the administration of justice. Professionals who tend to these victims should do so in an environment that provides support and comfort to the female victims, as the verification of injuries is often their first interaction with institutional authorities and can be decisive in their decision to proceed with legal action.

La violencia contra las mujeres es una de las violaciones más generalizadas de los derechos humanos. En estos casos, es frecuente encontrar lesiones en el área maxilofacial, las cuales pueden dejar secuelas de distinto tipo.

ObjetivoCaracterizar las lesiones maxilofaciales de las pericias realizadas bajo el Protocolo de Género en el Servicio Médico Legal Valparaíso, Chile.

MetodologíaEstudio cualitativo retrospectivo, realizado con datos recogidos de los peritajes maxilofaciales efectuados entre 2020 y 2023.

ResultadosSe analizaron 51 pericias. La edad de las víctimas osciló entre 21 y 73 años, la mayoría era dueña de casa, de estado civil soltera. En su mayoría, las agresiones fueron hechas por la pareja actual de las mujeres en el domicilio común. En casi un tercio de los casos, la agresión fue hecha en presencia de menores de edad. El mecanismo lesivo más utilizado fue el contuso, seguido del asfíctico. Existieron lesiones en tejidos blandos y duros. El pronóstico medicolegal en la mayoría de los casos fue menos grave.

DiscusiónEs fundamental la evaluación de las lesiones en el área maxilofacial por parte del dentista, especialmente para valorar lesiones intraorales. Los dentistas deben estar familiarizados con la lesionología en estos contextos, de modo de documentar correctamente las lesiones y aportar en la administración de justicia. Los profesionales que atienden a estas víctimas deberían hacerlo en un ambiente de acogida y contención, pues muchas veces la constatación de las lesiones es el primer acercamiento con la institucionalidad y puede ser determinante en su convicción de seguir adelante con la causa.

According to UN Women, gender-based violence is defined as harmful acts directed at a person or group of people based on their gender. The term is used to highlight the fact that structural power differentials based on gender place women and girls at risk of multiple forms of violence. Violence against women is one of the most widespread human rights violations in the world.1

Unlike other forms of violence where the aggressor tries to hide the injuries, one of the aims of violence against women is to damage their self-esteem and isolate them from the world. As a result, maxillofacial injuries are common, with the face being affected in 65–95% of cases.2,3 These injuries can leave various types of sequelae, the most common of which are aesthetic. However, it should not be forgotten that the head contains important anatomical structures, and therefore, injuries at this level can not only affect the soft and hard tissues but also cause changes in intermaxillary relationships and the temporomandibular joint, as well as neurological and sensory damage. In fact, it is common for victims of gender-based violence to suffer brain injuries as a result, which are significantly more common in absolute and percentage terms than those seen in people involved in contact sports and military activities.4

Common aspects of the study of maxillofacial injuries in gender-based violence are as follows: a higher prevalence of soft tissue injuries; punching is the most common mechanism of action used by aggressors; the middle third is the most commonly affected third of the face; the main aggressor is the current partner rather than ex-partners; and the most common location is in the home rather than in a public place.5–9 Although hard tissues are less commonly affected than soft tissues, the literature shows that injuries to these structures include nasal, mandibular, orbital, zygomatic, and dentoalveolar fractures.6–8,10,11 One study refers to dental trauma and reports the following injuries as a result of gender-based violence: coronary fracture, root fracture, subluxation, and intrusion.10

The most extreme expression of violence against women is femicide, defined as “the violent killing of women because of gender, whether it occurs within the family, the domestic unit or any interpersonal relationship, within the community, by any individual, or when committed or tolerated by the State or its agents, either by act or omission”. In Chile, there has been ongoing work to recognise femicide at a social and legal level, moving from the invisibility of the concept to the recognition of femicide-suicide through Law No. 21523 of 2022. The elements for classifying the crime of femicide in the new legislation are all crimes committed for gender-related reasons; they must be committed by a man; the term “women” encompasses gender diversity; these crimes can be committed in different stages of development (completed, frustrated, and attempted).12,13

The Clinical Unit for Injuries and Sexology of the Medical-legal Service (SML) of Valparaíso, at the request of the judicial authorities, undertakes expert assessments of injuries resulting from various crimes. The unit has a special protocol for victims of gender-based violence/attempted femicide/domestic violence, which takes into account several considerations: care is provided within the first 72 h of the request, the victim is supported and, if necessary, referred to the Intersectoral Femicide Network, and the report and its conclusions include a gender perspective.

The aim of this study is to characterise maxillofacial injuries in forensic examinations carried out under the Gender Protocol at the Chilean Medical-legal Service, Valparaíso headquarters, between 2020 and 2023.

MethodologyA retrospective qualitative study. An anonymised database was created with the expert reports of maxillofacial injury examinations carried out at the SML, Valparaíso headquarters, between 2020 and 2023. The examinations were performed on living female patients by a dentist specialising in legal and forensic dentistry. The injuries evaluated and included in this study were those of the maxillofacial region, while injuries outside this anatomical area were evaluated by a forensic doctor from the same unit and were not included in this study. The collection of this information began in 2021 as part of the research project Lesionología maxilofacial y dental en el SML, región de Valparaíso (Maxillofacial and dental injuries in the SML, Valparaíso Region). The following information was extracted from the database:

- -

Epidemiological data: expert reports by year and place of occurrence, characteristics of the victim and the aggressor.

- -

Injuries: mechanism of action, injuries to hard and soft tissues, medical-legal prognosis of the injuries.

- -

Special considerations.

An Excel spreadsheet was used to record the data. Statistical methods such as absolute and relative frequencies were used for descriptive analysis. Figures and tables were used to present the data.

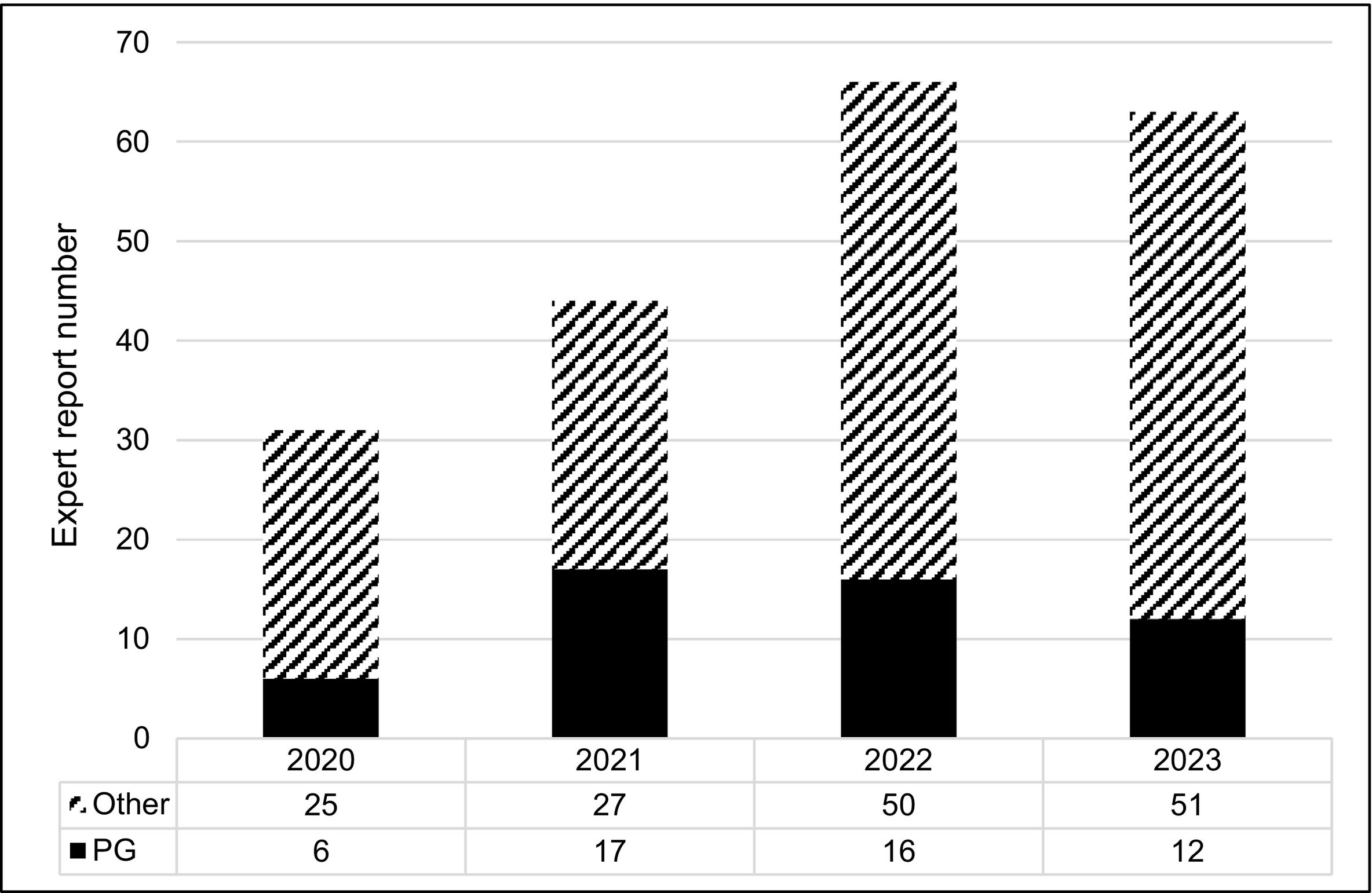

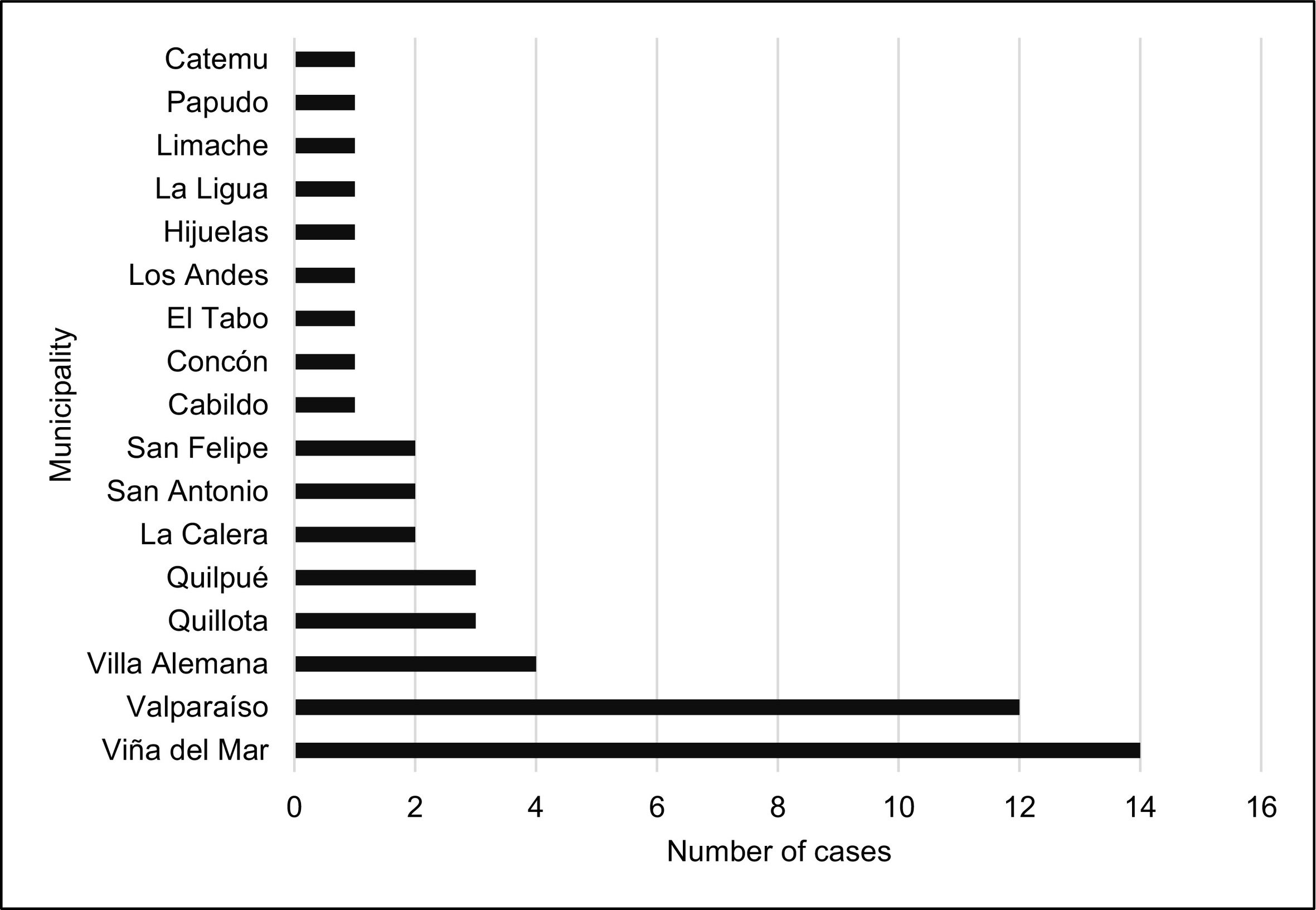

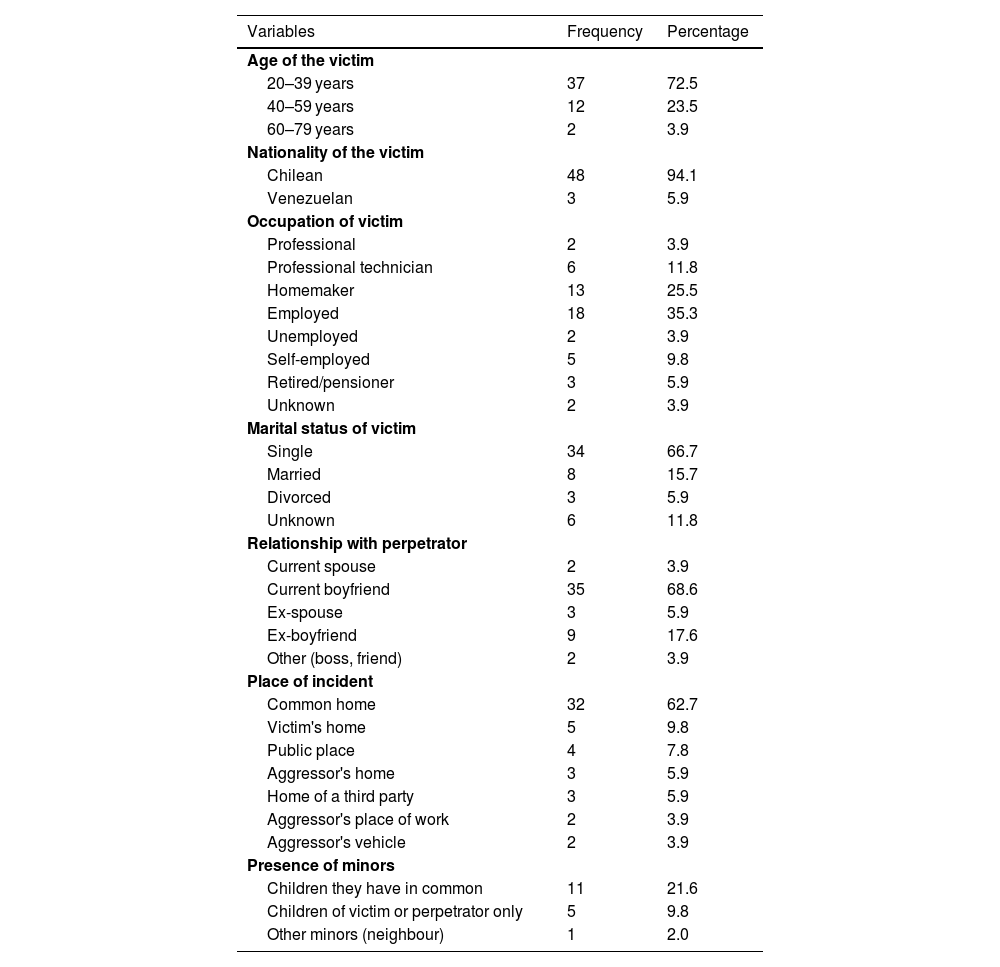

ResultsEpidemiologyBetween 2020 and 2023, 51 forensic examinations of maxillofacial injuries related to gender-based violence were undertaken, representing 25% of all forensic examinations (Fig. 1). The municipalities with the highest number of cases were Viña del Mar, Valparaíso, and Villa Alemana (Fig. 2). Victims ranged in age from 21 to 73, most were in their thirties and forties. Almost all the victims were Chilean nationals. The main occupations of the victims were homemakers and unskilled workers. In terms of marital status, 66.7% of the victims were single at the time of the incident (Table 1). Three of the women were pregnant at the time of the assault.

Epidemiological characteristics of the victim, relationship to the perpetrator, and place of the assault.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age of the victim | ||

| 20–39 years | 37 | 72.5 |

| 40–59 years | 12 | 23.5 |

| 60–79 years | 2 | 3.9 |

| Nationality of the victim | ||

| Chilean | 48 | 94.1 |

| Venezuelan | 3 | 5.9 |

| Occupation of victim | ||

| Professional | 2 | 3.9 |

| Professional technician | 6 | 11.8 |

| Homemaker | 13 | 25.5 |

| Employed | 18 | 35.3 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 3.9 |

| Self-employed | 5 | 9.8 |

| Retired/pensioner | 3 | 5.9 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3.9 |

| Marital status of victim | ||

| Single | 34 | 66.7 |

| Married | 8 | 15.7 |

| Divorced | 3 | 5.9 |

| Unknown | 6 | 11.8 |

| Relationship with perpetrator | ||

| Current spouse | 2 | 3.9 |

| Current boyfriend | 35 | 68.6 |

| Ex-spouse | 3 | 5.9 |

| Ex-boyfriend | 9 | 17.6 |

| Other (boss, friend) | 2 | 3.9 |

| Place of incident | ||

| Common home | 32 | 62.7 |

| Victim's home | 5 | 9.8 |

| Public place | 4 | 7.8 |

| Aggressor's home | 3 | 5.9 |

| Home of a third party | 3 | 5.9 |

| Aggressor's place of work | 2 | 3.9 |

| Aggressor's vehicle | 2 | 3.9 |

| Presence of minors | ||

| Children they have in common | 11 | 21.6 |

| Children of victim or perpetrator only | 5 | 9.8 |

| Other minors (neighbour) | 1 | 2.0 |

In 72.5% of cases, the aggressor was the victim's current partner. In 36 cases, the victim and the aggressor lived together (23 single women, 6 married women, 3 divorced women, and 4 women of unknown marital status). The most common location of the assault was the shared home. In 17 cases, the aggressor and the victim had children together: in 16 cases, the assault took place in the presence of minors, whether or not they were related to the victim and the aggressor (Table 1).

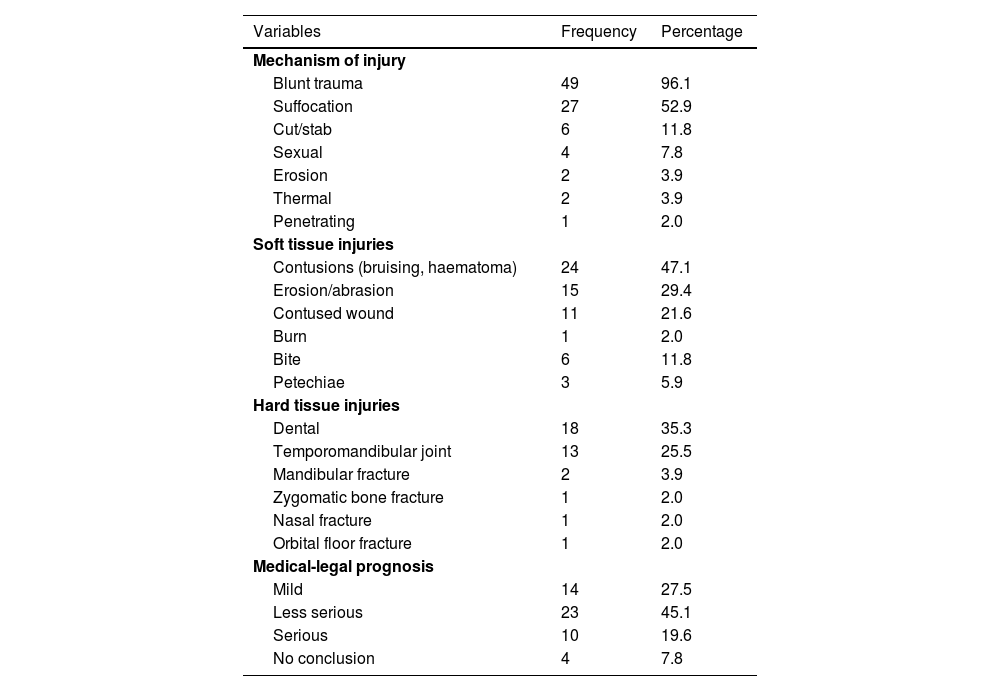

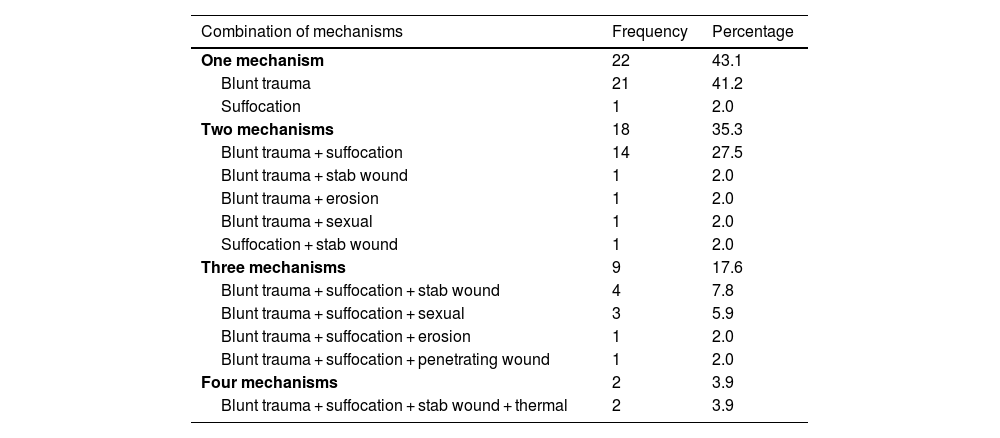

InjuriesThe most common mechanism of injury was blunt trauma (96.1%), and the most commonly used instrument was the perpetrator's body (fist in 42 of the 51 cases), followed by blunt objects (bottle, saucepan, belt, etc.), human bites, and forced insertion of the aggressor's fingers into the victim's nose, eyes, and mouth. The second most common mechanism was asphyxia (27 out of 51 cases), mostly due to non-fatal manual strangulation, followed by manual suffocation or suffocation with objects (pillow, tablecloth), and forearm strangulation. Other mechanisms described were: cutting/stabbing (with a knife); sexual, with vaginal, oral, and anal rape; erosive (with scratches and barbed wire); thermal (burns from petrol and hot water) and stabbing (assault with a sharp iron object known as a ‘diablo’) (Table 2). Of the 51 cases, 21 were assaults involving only blunt trauma (41.2%), while 29 involved a combination of more than one mechanism: the most common combination was blunt force plus suffocation (27.5%), accompanied by a third or even fourth mechanism (Table 3).

Distribution of mechanisms, injuries, and their medical-legal prognosis.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| Blunt trauma | 49 | 96.1 |

| Suffocation | 27 | 52.9 |

| Cut/stab | 6 | 11.8 |

| Sexual | 4 | 7.8 |

| Erosion | 2 | 3.9 |

| Thermal | 2 | 3.9 |

| Penetrating | 1 | 2.0 |

| Soft tissue injuries | ||

| Contusions (bruising, haematoma) | 24 | 47.1 |

| Erosion/abrasion | 15 | 29.4 |

| Contused wound | 11 | 21.6 |

| Burn | 1 | 2.0 |

| Bite | 6 | 11.8 |

| Petechiae | 3 | 5.9 |

| Hard tissue injuries | ||

| Dental | 18 | 35.3 |

| Temporomandibular joint | 13 | 25.5 |

| Mandibular fracture | 2 | 3.9 |

| Zygomatic bone fracture | 1 | 2.0 |

| Nasal fracture | 1 | 2.0 |

| Orbital floor fracture | 1 | 2.0 |

| Medical-legal prognosis | ||

| Mild | 14 | 27.5 |

| Less serious | 23 | 45.1 |

| Serious | 10 | 19.6 |

| No conclusion | 4 | 7.8 |

Details of the harmful mechanisms of injury used.

| Combination of mechanisms | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| One mechanism | 22 | 43.1 |

| Blunt trauma | 21 | 41.2 |

| Suffocation | 1 | 2.0 |

| Two mechanisms | 18 | 35.3 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation | 14 | 27.5 |

| Blunt trauma + stab wound | 1 | 2.0 |

| Blunt trauma + erosion | 1 | 2.0 |

| Blunt trauma + sexual | 1 | 2.0 |

| Suffocation + stab wound | 1 | 2.0 |

| Three mechanisms | 9 | 17.6 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation + stab wound | 4 | 7.8 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation + sexual | 3 | 5.9 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation + erosion | 1 | 2.0 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation + penetrating wound | 1 | 2.0 |

| Four mechanisms | 2 | 3.9 |

| Blunt trauma + suffocation + stab wound + thermal | 2 | 3.9 |

The resulting injuries can manifest themselves in the soft and hard tissues of the maxillofacial region. The most common soft tissue injuries were blunt trauma (bruises, haematomas) of the face and mouth. These were followed by erosions and abrasions, blunt trauma (including one lip laceration), and burns (Table 2). Human bites were not found in the maxillofacial area, but on other parts of the victim's body: fingers (2), thigh/buttocks (2), forearm/arm (2), hand (1) and back (1).

In 3 cases, petechiae were observed on the soft and hard palate. In these three cases, the mechanism of injury was a combination of blunt trauma and suffocation, with strangulation in two cases and strangulation and suffocation in one case.

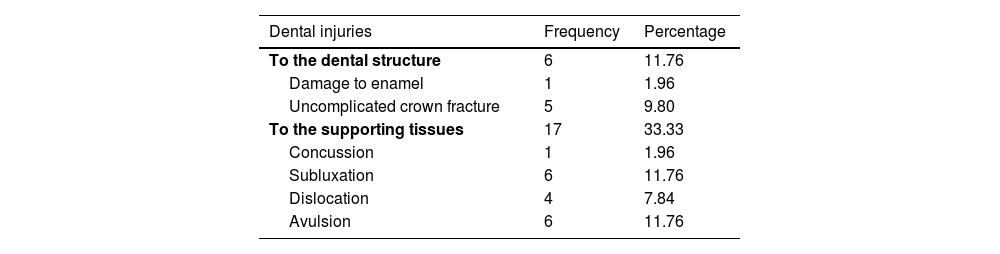

In terms of hard tissues, the teeth were most affected, with varying degrees of damage to both the dental structure and the periodontal support tissues (Table 4). This was followed by temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involvement, which in four cases was not accompanied by soft tissue injury, i.e. the TMJ sequelae (limited mouth opening, joint pain, joint noises) were the only objective manifestation of the assault. With regard to bone fractures, there are two cases of mandibular fractures, one zygomatic fracture, one nasal fracture, and one orbital floor fracture. The presence of these injuries is associated with a blunt trauma mechanism (Table 2).

With regard to the medical-legal prognosis, most of the injuries were classified as less serious or moderately serious. In four cases, it was not possible to complete the medical-legal report due to a lack of background information (Table 2). In all cases considered to have a serious medical-legal prognosis, there were injuries to hard maxillofacial tissue.

Special considerationsIn 8 of the cases, the report was issued “on the basis of the background information”, i.e., there was no physical examination of the victim, but only an analysis of the documents describing the facts provided by the prosecution. These cases were due to the victims' inability to travel, the time limits for the completion of the investigation, and the withdrawal of the complaint by the victim. With regard to the crime under investigation, in 23 cases, the crime classified in the official letter ordering the expert examination was related to gender and domestic violence crimes (sexual crimes, femicide, attempted femicide, intimate and non-intimate femicide, serious or less serious injuries in cases of domestic violence) and the expert examination was requested from the outset by the Public Prosecutor's Office with a gender perspective.

In 2 of the cases, the victim was held against her will and therefore abducted.

DiscussionIn terms of the number of cases handled, there were significantly fewer cases in 2020 than in the 3 subsequent years included in the study. It should be remembered that the country was in the midst of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020, which meant that, given the specific characteristics of forensic injury assessment, it was suspended in the country from the start of the pandemic lockdown in March until health conditions allowed it to resume in September of that year.

In terms of the characteristics of the assault, the results obtained for the victims in the region are broadly consistent with those described in the international literature on the subject5–11: the victims examined are all cisgender women, and the assaults occurred in a higher percentage of women between the ages of 30 and 50. The women had different levels of education, with a higher prevalence of unskilled workers and homemakers. With regard to marital status, there is a deviation from what is reported in the international literature, which shows a higher number of married women: the results of this study show that most of the victims were single at the time of the events (66.7%) and only 15.7% of them were married.

With regard to the aggressor, the data from this study, like those from others, agree that the person in the current emotional relationship is most often the aggressor (72.5%); however, our findings show that these men are mostly not spouses, but other types of partners, such as a boyfriend (94.6%). It is worth noting the two cases in which the aggressor did not have a sexual or emotional relationship with the victim, but another type of relationship (boss, friend), highlighting that violence against women occurs not only in intimate contexts but also in other contexts, such as the workplace. The context of the assault is mostly domestic, whether in a shared home (70.6% of victims lived with their aggressor), in the victim's home, in the aggressor's home or in the home of a third party known to both. These data are in line with previous research on this topic.

Other important aspects are the presence of minors at the time of the assault and the pregnancy status of the victim. There are 16 cases where the assault took place in the presence of minors, 68.8% of whom were children of both the aggressor and the victim. In terms of pregnancy, three of the victims were pregnant at the time of the assault. For decades, the Chilean state, judicial auxiliaries, and civil society organisations have been committed to recognising violence against women and ensuring that ad hoc regulations are in place. This is reflected in the evolution of legislation, starting with the invisibility of the phenomenon, through the recognition of the crime of femicide in marital or cohabiting relationships (intimate femicide, defined in Law No. 20480 of 2010), to the definition of the new crime of broad, intimate, and non-intimate femicide in Law No. 21212 of 2020 (known as the Gabriela Law), and finally the recognition of femicide-suicide as a criminal offence in Law No. 21523 of 2022, or the Antonia Law.13–15 Specifically, the Gabriela Law of 2020 recognises four aggravating factors for criminal responsibility for the crime of femicide: the victim is pregnant; the woman is a minor, elderly, or disabled; the attack is committed in the presence of the victim's ascendants or descendants; and the attack is committed in the context of habitual violence (Law No. 21212).15 It is essential that healthcare professionals report the presence of these aggravating circumstances, either at the time of the initial assessment of the injuries or during the examination of the injuries, by carefully recording the user's account and objectively verifying it with the available documentation, in order to ensure better administration of justice at a later stage.

As has been widely reported in the scientific literature, the most common injuries are those to the soft tissues of the midface: bruises and haematomas, abrasions, and blunt trauma wounds. Less common were injuries caused by human bites: the presence of these injuries highlights the importance of examination by a dentist, who is the professional best qualified to describe them due to their specific characteristics. Bites can also be useful in criminal investigations, as some authors propose a profile of the aggressor who bites as a person with childhood conflicts and some kind of anxiety disorder, whose decision to bite reflects their attempt to control the situation. The location of the bite can also provide clues as to its intention: the presence of these injuries on the fingers or upper limbs can indicate defensive injuries, while in areas with sexual connotations, they can indicate assaults with a strong sexual and submissive component.16 In the cases analysed in this study, five of the human bite injuries are on the fingers, hands, and arm, while three are on the buttocks, thighs, and back, indicating defensive and sexual injuries, respectively.

The most common mechanisms of injury were blunt trauma, suffocation, and a combination of both (70.6%). Consistent with the literature, we found that blunt trauma was the most common mechanism, with the aggressor using their own body (fists, feet) or a blunt object, usually a household item that was readily available at the time. A significant finding of this study was that in almost 10% of cases, the aggressor forcibly inserted his fingers into the victim's nose, mouth, and eyes. This type of aggression was not reported in the literature reviewed, highlighting the importance of careful examination of the oral, nasal, and ocular mucosa of victims so that these signs do not go unnoticed or are not omitted from the findings or expert reports of injuries.

With regard to the mechanism of suffocation, it should not be forgotten that non-fatal strangulation is a serious form of assault, often seen in gender-based violence and considered a separate crime in many jurisdictions (United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, Australia). It involves the total or partial occlusion of the airways and blood vessels by pressure on the neck and, although it often leaves no visible marks on the victim's skin, it can cause a range of injuries and sequelae, both acute (bruising, petechiae, difficulty swallowing or breathing, arterial dissection) and long-term (stroke, brain damage, seizures, motor disorders, memory loss, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal tendencies, miscarriages, premature births, and many others). The literature reports that women are 13 times more likely to suffer this form of violence and it is therefore a marker of escalating violence and a predictor of future more serious and even fatal attacks (the literature refers to a 7.5 times higher likelihood of future fatal attacks).17,18 The most common injuries seen in non-fatal strangulation are, in descending order: erythema/ecchymosis/haematoma on the neck, cervical abrasions, petechiae, subconjunctival haemorrhage, and ligature marks.18 Among the injuries assessed in the examination of injuries by a dentist or in the expert assessment of maxillofacial injuries, it is particularly important to correctly document the presence of petechiae. Petechiae are extravasations of blood from superficial vessels caused by an asphyxial mechanism (strangulation, aspiration, suffocation, among other causes), appearing clinically about 20–30 s after occlusion. They can be seen on the face and the ocular, nasal, tympanic, and oral mucous membranes. Although they are transient lesions, they are considered a predictor of death, and it is recommended that those who have presented them remain under medical observation for the first 12 h after the attack.17 When there is a report of suffocation, it is essential to have a dentist examine the patient to confirm not only the presence of petechiae but also other injuries that may indicate this mechanism (teeth marks on the mucous membranes of the inner lips and cheeks, perioral erosions, and abrasions).

The most common hard tissue injuries were, in descending order, dental, joint, and bone. Although described in the literature as less common than soft tissue injuries, they should not be overlooked, as they are often the most serious and can leave long-lasting or even permanent sequelae. It should be noted that many authors emphasise the under-reporting of dental and dentoalveolar injuries, probably because the initial assessment of injuries in the emergency department is made by a physician.19 In fact, most of the sequelae of GBV injuries in the maxillofacial region are found in the teeth and periodontal tissues, and the most commonly described are difficulties in chewing, chronic pain, and changes in tissue mobility. All of these have a significant impact on both social interaction and the personal life of the victim.5

It should be remembered that one of the essential components of gender-based violence is that it is a structural part of contemporary society, based on gender roles and sexual stereotypes that reproduce a social organisation in which women are in an inferior position to men. This cross-cutting nature, and the fact that this type of violence is often validated by some sectors of society, means that victims are slow to report it. Furthermore, it is essential to respond quickly to victims, as a significant percentage of them withdraw their complaints for various reasons (economic or emotional dependence on the aggressor, threats of future injury or death, distrust of the system, etc.), which can lead to the aggressors going unpunished. We must therefore make every effort to ensure that the process takes place in an environment that is welcoming and supportive of women victims, bearing in mind that this is likely to be their first contact with the institutions after the act of violence and may be decisive in their decision to pursue the case.

FundingThe authors declare that this work was carried out within the framework of the research project Lesionología maxilofacial y dental en el SML, Región de Valparaíso, authorised by the Carlos Ybar Research Institute in June 2021. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Lagos Tissie D, Faúndes Pinto M, Silva Melo J, Montoya Barrena A, Contreras Vicencio C. Maxillofacial injury in gender violence: Descriptive study of cases from Valparaíso, Chile. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2025.500458.