Ocular involvement in AIDS patients is a common event mainly caused by inflammation or infection. Despite the high prevalence rate of cryptococcosis in these individuals, ocular features have been occasionally described.

Case reportA 20-year-old Brazilian female with HIV infection recently diagnosed was admitted with a respiratory profile presumptively diagnosed as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; an ophthalmologic exam suggested choroiditis by this agent as well. She was complaining of headaches and blurred vision which led to cryptococcal meningitis diagnosis by a CSF positive India ink stain and Cryptococcus neoformans positive culture. Despite therapy based on amphotericin B plus fluconazole, her clinical state progressively worsened and the patient died one week later. At necropsy, disseminated cryptococcal infection was evidenced in several organs including eyes, which presented bilateral chorioretinitis.

ConclusionsCryptococcal ocular involvement in AIDS patients has been occasionally proved among the cases already reported. Thus, the post mortem exam is still pivotal to improve the quality of the clinical diagnosis, especially in limited-resource settings.

La afectación ocular en pacientes con sida es una circunstancia común provocada principalmente por procesos inflamatorios o infecciosos. A pesar de la alta prevalencia de criptococosis en estos individuos, los hallazgos oculares solo se describen ocasionalmente.

Caso clínicoUna mujer brasileña de 20 años, diagnosticada poco tiempo antes de infección por el VIH, fue hospitalizada por dificultad respiratoria con el presunto diagnóstico de neumonía por Pneumocystis jirovecii; el examen oftalmológico sugirió también la existencia de coroiditis por el mismo agente etiológico. Las quejas de la paciente por cefalea y visión borrosa orientaron el diagnóstico hacia la criptococosis meníngea, confirmada por el examen directo y el crecimiento de Cryptococcus neoformans en el cultivo del líquido cefalorraquídeo. A pesar de haber comenzado un tratamiento con anfotericina B y fluconazol, el estado clínico empeoró progresivamente y la paciente falleció una semana después. La necropsia mostró criptococosis diseminada en varios órganos, incluidos los ojos, que presentaban coriorretinitis bilateral.

ConclusionesLa criptococosis ocular en pacientes con VIH se ha descrito ocasionalmente en los casos publicados. Por este motivo, la necropsia todavía es fundamental para mejorar la calidad del diagnóstico clínico de esa enfermedad, especialmente en regiones con recursos limitados.

Cryptococcosis leads the cause of mortality among HIV/AIDS patients, and is the third opportunistic AIDS defining illness in limited-resource settings where, at admission, most patients present advanced immunodeficiency and disseminated fungal infection.20,21 Ocular features associated to cryptococcal meningitis include arachnoiditis and optic nerve lesions due to the intracranial increased pressure, whereas primary choroidal involvement is the most typical presentation of cryptococcal endophthalmitis. Most cases of ocular involvement can precede or follow cryptococcal meningitis as a result of hematological dissemination or the infection of nearby tissues as leptomeninges.29,30

Until 1968, 13 cases of cryptococcal chorioretinitis had been reported; most of them progressed naturally bad since amphotericin B was not yet available.14 Another review in 1991 included 20 patients of whom over one-half were apparently immunocompetent.9 In another 1992 report, including 27 cases, only 8 cases were new ones, and the rest had been already included in the review of 1991.8,9 Most patients received amphotericin B alone or combined with 5-fluorocytocine. In spite of that, a poor outcome was evidenced in most cases, leading to enucleation, death or permanent visual impairment.8,9 Only three cases of the later review were associated to HIV infection.8

A case series of AIDS patients diagnosed at necropsy evaluated18 multifocal choroiditis cases of which only 7 were caused by Cryptococcus neoformans.16 Later on, the cases of six HIV-infected patients with presumptive cryptococcal chorioretinitis were published. One of these cases had been already included in the report of 1992.8,13 Afterwards, new cases of cryptococcal primary ocular involvement mostly associated to HIV-infected patients were reported.1–5,7,10,12,13,17,19,22–24,26-28,30 Cryptococcal chorioretinitis diagnosis in this population can be a challenge due to the clinical similarity with other more common clinical profiles due to agents such as Toxoplasma gondii, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and other herpes virus infections which primarily infect the retina rather than the choroid.

This report describes the case of a cryptococcal chorioretinitis (post mortem confirmation) secondary to disseminated fungal infection in a HIV-infected patient exam.

Case reportA 20-year-old Brazilian female was admitted to our teaching hospital. She referred a two-month history of cough, daily fever and a weight loss of 9kg. Due to the symptoms suggestive of severe anemia, she had been previously admitted in another hospital where pancytopenia and HIV infection were diagnosed. There she received blood transfusion and the antiretroviral therapy, which was stopped one week later due to gastric intolerance and worsening of her clinical state.

At admission, she complained of dry cough, progressive dyspnea, blurred vision and headache. At clinical exam she presented mild mental confusion, intense malnutrition, cutaneous and mucosal pallor, acrocyanosis, and severe respiratory distress. No other neurological findings were found. The hemogram showed pancytopenia, and the chest X-ray evidenced homogeneous, bilateral and symmetrical pulmonary interstitial infiltrates. A presumptive diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia was raised and intravenous sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim plus hydrocortisone were administered, and another blood transfusion was performed. The ophthalmologic exam suggested bilateral chorioretinitis by this fungus but the basis for this clinical impression was not registered.

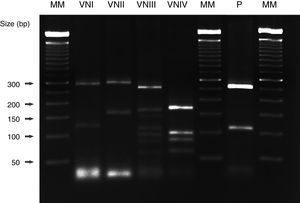

Cryptococcal meningitis was confirmed by a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) positive India ink stain, latex-Cryptococcus antigen detection (IMMY Mycologics Inc., OK, USA) positive test and a CSF C. neoformans positive culture as well. The clinical isolate was identified as C. neoformans VNI genotype by orotidine monophosphate pyrophosphorylase (URA5) gene restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (Fig. 1). The CD4+ T cell and viral load assessment of the patient were unavailable at the time. Despite administering amphotericin B plus fluconazole, the clinical status progressively worsened: the patient suffered spontaneous gingival bleeding, skin hematomas and died at day 7 after hospitalization.

URA5-RFLP patterns obtained after double digestion with the enzymes Sau 96I and Hha I. Several Cryptococcus neoformans strains with different genotypes, as well as the strain isolated from our patient (C. neoformans var. grubii, genotype VNI) were included. MM: 50bp molecular marker (Bionner, USA); VNI: WM 148; VNII: WM 626; VNIII: WM 628; VNIV: WM 629; P: patient.

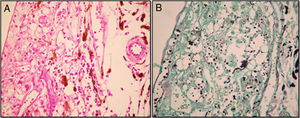

Necropsy was performed with the family consent, and the medical pathologist was asked to evaluate ocular structures. At post mortem exam, the corporal mass index was 12.8kg/m2. A disseminated cryptococcal infection to brain, meninges, bone marrow, lungs, stomach, colon, liver, spleen, thyroid gland, adrenal glands, pancreas, kidneys and eyes was observed. A mild inflammatory process composed by macrophages, lymphocytes and a great number of yeasts similar to C. neoformans along the choroid was evidenced in both eyes (Fig. 2). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) lesions along the esophagus, and an oropharingeal Candida infection were also seen. Pulmonary or ocular P. jirovecii infections were not found.

(A) Mild inflammatory infiltrate composed of histiocytes and lymphocytes along the choroid with structures suggestive of Cryptococcus (original magnification 40×, H&E stain). (B) The Grocott's methenamine silver stain confirmed the presence of yeasts consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans (original magnification 40×; GSM stain).

Until the early 80s, no more than 500 cases of cryptococcosis had been reported around the world. However, an unexpectedly increased number of patients with cryptococcal meningitis occurred following the pandemic AIDS era. Nearly one million cryptococcal cases per year were estimated in 2009, with a mortality rate of 50–70% mostly in Africa, Asia and Latin America. There, most HIV-infected patients present advanced immunodeficiency and disseminated fungal infection at admission. These facts may explain the unacceptable high mortality rate despite the antiretroviral therapy at free disposal has progressively increased around the world.20 However, a recent report pointed out a remarkable decrease of cryptococcosis mortality rates mainly in Africa.21

The patient was at first presumptively diagnosed of P. jirovecii pneumonia due to her severe and protracted respiratory picture, in addition to the intensity of interstitial and bilateral infiltrates pattern seen at the chest X-ray. P. jirovecii ocular involvement has been occasionally observed in AIDS patients receiving aerolized pentamidine to prevent Pneumocystis infection in the late 80s, but has been rarely reported after sulfonamides prophylaxis.11,25 Cryptococcal meningitis was diagnosed due to her neurological profile. Although the CD4+ T count was unavailable at the time of necropsy, the severity of organ involvement by the cryptococcal infection and the concomitant CMV infection support the fact that the patient suffered an advanced immunodeficiency similar to most of the cases already reported.20,21

Disseminated cryptococcosis can result in infectious microemboli that lodge in the choroidal circulation, which may lead to multiple patterns of lesions in the posterior pole, although these lesions are not pathognomonic of any particular infectious agent.26,31 This aspect is the most typical picture of cryptococcal endophthalmitis and may help to distinguish it from that caused by CMV, T. gondii, herpes virus and Candida, among others.6,15 According to other authors, some findings such as visual deficit, neural atrophy, papilledema and choroidal infiltrates can raise the suspicion of cryptococcal infection.16 However, these signs can also be observed in endophthalmitis caused by other microorganisms, which leads to misdiagnosis and therapeutic difficulties, especially in patients suffering only ocular involvement. Chorioretinitis, multifocal choroiditis, neuroretinitis, vitritis or endophthalmitis are the most common clinical presentation of ocular cryptococcosis.16,27 Therefore, a careful clinical history, physical exam and complete laboratorial assessment must be undertaken to diagnose primary or secondary cryptococcal ocular involvement.

According to the literature reviewed until 1996, 53 cases of cryptococcal endophthalmitis were reported.8,9,14,30 Among these cases, the predominant clinical picture was meningitis associated to ocular symptoms, which sometimes preceded or followed the involvement of other anatomical sites. Nearly 50% of these patients suffered underlying predisposal medical conditions, and 37 (71%) were diagnosed with cryptococcal choroiditis by cytological or histopathologic exam of aqueous or vitreous humors aspirate, or as a necropsy finding. In the remaining cases this diagnosis was presumptive and associated with the presence of Cryptococcus infection in another anatomical site. Nearly half of these patients died, and those who survived had poor outcome related to vision, with partial or definitive loss. Fifteen (29%) patients out of the 53 cases concomitantly suffered meningitis or disseminated infection and had a poor outcome.

A research of cryptococcal choroiditis cases published after 1996 was carefully performed. To our knowledge, the cases of 24 new patients have been reported since then; clinical data of 20 patients (Table 1) were available. Fifteen (75%) of them were male, the median age was 36.8 years, and 17 (85%) patients were HIV-infected. The latter percentage contrasts with that observed before 1996 (30%). This fact would be partially explained by the improvement of clinical suspicion of this etiology and the diagnostic methods, together with the remarkable interest on cryptococcosis as one of the more prevalent AIDS defining condition around the world.21 Ten out of the 20 patients (50%) suffered disseminated cryptococcosis, whereas 8 (40%) had cryptococcal meningitis together with chorioretinitis. Among the 20 chorioretinitis cases, only 6 (30%) had ocular cryptococcal etiology confirmed through different methods (Table 1).1,8,9,12,15,16 In the remaining cases the cryptococcal infection was evidenced by culture, India ink stain and CrAg positive in other fluids or sites, but the ocular involvement was only presumptive. Most patients received amphotericin B, alone or combined with fluconazole or flucytosine. Thirteen (65%) recovered or had their ocular lesions improved, and the remaining 7 (35%) died on therapy or later of unknown causes.

Update of cryptococcal chorioretinitis cases published after 1996.

| Case | Age | Gender | Underlying disease | Symptoms | Clinical diagnosis | Diagnostic methods | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 22 | M | HIV-infected and hemophilia A | Fever, cough | Cryptococcal choroiditis | Post mortem | None | Exitus |

| 230 | 39 | M | HIV-infected and Kaposi's sarcoma | Blurred vision | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: CrAg, culture | AMB+FLZ | NA |

| 312 | 40 | M | HIV-infected | Fever, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: India ink, CrAg, culture. Blood culture | AMB+5FC | Exitus |

| 423 | 43 | M | HIV-infected and hepatitis C | Bilateral visual loss | Cryptococcal and CMV bilateral choroiditis | CSF culture, bone marrow biopsy | AMB | Exitus |

| 522 | 28 | M | HIV-infected | Blurred vision, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF, blood, lung tissue and urine culture | AMB+5FC | Recovery |

| 622 | 32 | M | HIV-infected | Blurred vision, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF, blood culture | AMB+5FC | Recovery |

| 722 | 27 | M | HIV-infected | Diplopia, blurred vision | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: CrAg, culture | AMB+5FC | Recovery |

| 84 | 37 | M | Renal transplanted | Blurred vision | Disseminated cryptococcosis | Vitreous aspirate culture | AMB+FLZ | Improvement |

| 926 | 45 | F | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Progressive visual loss | Cryptococcal endophthalmitis | Retinal biopsy | AMB+FLZ | NA |

| 1010 | 44 | F | HIV-infected and hepatitis C | Blurred vision, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: CrAg, blood culture | AMB+5FC+FLZ | Improvement |

| 1117 | 30 | M | HIV-infected | Progressive visual loss | Disseminated cryptococcosis | Limbal biopsy | AMB | Exitus |

| 121 | 27 | F | HIV-infected | Fever, headache | Neurotoxoplasmosis, disseminated cryptococcosis | Post mortem | AMB+FLZ | Exitus |

| 1324 | 28 | M | HIV-infected | Blurred vision, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: India ink | AMB+FLZ | Exitus |

| 143 | 30 | M | HIV-infected | Assymptomatic | Cryptococcal meningitis | CSF: India ink, CrAg | AMB+FLZ | Exitus |

| 1519 | 52 | M | Apparently immunocompetent | Dacryorrhea | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CrAg in CSF, aqueous humor and prostate fluid | AMB+5FC | Recovery |

| 1628 | 39 | M | HIV-infected | Floaters in left eye | Cryptococcal chorioretinitis, IRIS | Vitreoretinal biopsy | AMB+FLZ | Retinal detachment |

| 175 | 42 | M | HIV-infected | Vision loss, headache | Cryptococcal choroiditis | CSF: India ink, culture | AMB+FLZ | Improvement |

| 187 | 42 | M | HIV-infected | Severe headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: CrAg, culture. Serum: CrAg | AMB+5FC+FLZ | Recovery |

| 1913 | 30 | M | HIV-infected | Blurred vision, headache, seizures | Cryptococcal choroiditis, optical neuropathy | CSF: India ink+CrAg+culture Urine: culture | LAmB+FLZ | Recovery |

| 202 | 37 | M | HIV-infected | Decreased visual acuity, headache | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF India ink | AMB | Exitus |

| PR | 20 | F | HIV-infected | Headache, blurred vision | Disseminated cryptococcosis | CSF: India ink+CrAg+culture. Post mortem | AMB+FLZ | Exitus |

Abbreviations: M: male; F: female; CMV: cytomegalovirus; IRIS: immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; CrAg: cryptococcal antigen; AMB: amphotericin B; LAmB: liposomal amphotericin B; FLZ: fluconazole; 5FC: flucytosine; NA: not available; PR: present report.

Currently, it is really worrying that necropsies proceedings in teaching hospitals around the world have progressively decreased during the last years. On the other hand, the population of immunocompromised individuals has grown and high mortality rates are still registered due to non-confirmed presumptive diagnoses, and empiric therapies are based on the severity of clinical pictures. Therefore, the post mortem exam is still pivotal, the only way to improve the quality of the clinical diagnosis and to better understand the poor outcome of these patients as the case herein reported.

Ethical statementThis study was approved by the Ethical Research Board of the Triângulo Mineiro Federal University under protocol number 2526.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest among the authors of this report.

We are grateful to Mrs Angela Azor for the technical assistance and to CNPq grant 470224/2012-6 and FAPEMIG grant APQ 01624-12 for the financial support.