This study examines how audit-related governance mechanisms influence corporate fraud risk, utilising data from 1025 non-financial EU firms between 2018 and 2023. The dependent variable, fraud risk, is proxied by the Beneish M-Score. The independent variables examined comprise six key audit characteristics: the existence of an audit committee, audit committee financial expertise, audit fees, mandatory auditor rotation, the reporting line of the internal audit function, and external assurance of non-financial reports. The theoretical framework integrates agency theory and stakeholder/legitimacy theory, suggesting that both traditional and innovative audit mechanisms may deter financial misreporting. Methodologically, the panel Estimated Generalised Least Squares method with cross-sectional weights was employed. Empirical results show that all the considered audit characteristics significantly affect fraud risk in the expected direction. In particular, traditional agency-based mechanisms (audit committee presence, financial expertise, and lower audit fees) and legitimacy-driven innovative practices (auditor regular rotation, independent internal audit reporting, and external non-financial reporting assurance) are each associated with lower fraud risk. These relationships remain robust when using an alternative statistical technique (Generalised Method of Moments) and a different measure for the dependent variable. Our research holds significant implications as it provides valuable insights for scholars and regulators focused on reducing earnings manipulation and improving integrity within EU capital markets.

Corporate financial fraud continues to be a widespread issue, damaging market trust and incurring substantial social, reputational, and economic costs. Major scandals such as Enron, Parmalat and WorldCom led to billions in shareholder losses and damaged public trust in corporate financial reports (Cumbana & Ventura, 2024; Rezaee, 2005; Wehrhahn & Velte, 2024).

In response to such events, policymakers worldwide have tightened audit regulations. In the US, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (Securities and Exchange Commission, 2002) imposed strict requirements to increase auditor independence and enhance internal control requirements (Wehrhahn & Velte, 2024). In the European Union, Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 delineates the statutory audit requirements for public interest entities (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2014a, 2014c; Florio, 2024). Furthermore, Directive 2014/95/EU on Non-Financial Reporting seeks to enhance the quality and transparency of audits (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2014b; Mion and Adaui, 2020). These reforms mandate the creation of independent audit committees, usually consisting of financial experts, and require significant EU public-interest entities to provide information related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors as well as anti-corruption initiatives. Furthermore, the recent Directive (EU) 2022/2464 expands this framework by including more companies, establishing comprehensive sustainability reporting standards, and requiring mandatory external assurance for non-financial reports (The European Parliament, 2022). As a result, audit committees and auditors are now responsible for overseeing non-financial reporting with the same diligence as financial reporting. EU frameworks now require ESG and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting and auditing to be fundamental elements of corporate governance.

The series of financial failures and scandals, alongside the evolving legislative directives, highlight the necessity of implementing a comprehensive range of fraud-prevention strategies (Bonrath & Eulerich, 2024; Wehrhahn & Velte, 2024). In particular, one of the most effective mechanisms, closely associated with corporate entities, is the audit function that involves external audit, internal audit, and the audit committee. External auditors act as an external governance instrument, assessing the company’s internal control system and verifying financial reports to detect and report instances of fraud (Halbouni, 2015; Sitanggang et al., 2020). Internal auditors’ primary task is to oversee a company’s internal governance mechanisms by evaluating and improving risk management, control, and governance processes (Munro & Stewart, 2011). Lastly, the audit committee oversees all audit activities by discussing financial reporting accuracy with managers, ensuring the independence of external auditors, collaborating with internal auditors on control activities, and sharing relevant information with external auditors as needed (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2022; Stewart & Munro, 2007). Indeed, research indicates that internal auditors, audit committees, and external auditors serve as essential pillars for effectively reducing fraud (Ahmed et al., 2021; Alzoubi, 2019; Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023; He & Yang, 2014).

Despite the acknowledged importance of audit oversight, existing academic research reveals significant gaps. Many previous studies examine individual audit variables in isolation and often focus on single-country samples (Johnson et al., 2002; Kamarudin et al., 2022; Krishnan & Lee, 2009; Litt et al., 2014). Moreover, the theoretical lens is typically narrow, only applying agency theory rather than integrating multiple perspectives. Consequently, an incomplete picture is presented that lacks integrated evidence on how coexisting audit mechanisms collectively influence fraud risk, particularly in the diverse European context. In particular, innovative governance features, such as mandatory sustainability reporting and internal audit reporting lines, have not been thoroughly explored in fraud-risk models. This drives the need for a comprehensive study that addresses these gaps.

To address the identified gaps, this study conducted a multinational empirical analysis using a panel of 1025 publicly listed firms across various industries throughout all European Union countries for the period 2018–2023. To investigate the relationship between audit mechanisms and fraud risk through statistical analysis, panel econometrics using the Estimated Generalised Least Squares (EGLS) method was employed. The dependent variable examined is fraud risk, assessed through the Beneish (1999) M-score. This established mathematical tool considers eight financial ratios to predict the probability of fraudulent activities in the form of earnings manipulation. By applying the M-score to a wide sample of European companies from different industries and countries, this research uncovers subtle indicators of earnings management prior to formal restatements or enforcement actions. This approach complements traditional binary fraud proxies, such as restatements or enforcement actions, and aligns with ongoing efforts to develop early-warning mechanisms. In investigating the influence of audit instruments on fraud risk, this study considers six audit-related characteristics that could impact corporate fraud risk. Three of these (the existence of an audit committee, the financial expertise of committee members, and audit fees) represent traditional audit mechanisms rooted in agency theory, which addresses conflicts between managers and shareholders. The other three audit characteristics (auditor rotation, independence in internal audit reporting, and external assurance of non-financial disclosures) are innovative and derived from stakeholder and legitimacy theories. Control variables include board size, firm size, and a COVID-19 period dummy. Moreover, the statistical analysis incorporates fixed effects for country and industry to account for unobserved heterogeneity across regions and sectors. By simultaneously focusing on different aspects of audit governance and utilising a predictive fraud indicator, this analysis uncovers complex relationships that studies constrained to one variable and one country fail to reveal. Additionally, robustness tests were undertaken applying dynamic Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) as a check to address potential endogeneity issues and an alternative measurement for the dependent variable.

The findings show that all six audit attributes examined influence fraud risk. Traditional agency-based mechanisms, such as having an audit committee and the presence of members with financial expertise, reduce earnings manipulation. In contrast, higher audit fees correlate with increased fraud risk, indicating that auditors charge risk-based premiums for firms with greater misstatement expectations. Lastly, stakeholder-oriented variables, namely mandatory auditor rotation, an independent internal audit reporting line, and external assurance of non-financial reports, are associated with lower fraud risk. These results emphasise the combined roles of agency and stakeholder perspectives in corporate governance, suggesting that strong audit oversight and transparency improve financial reporting integrity. The findings are consistent across different model specifications and an alternative Beneish M-score, highlighting their robustness.

This paper offers several contributions to both practice and theory. Firstly, it conceptually integrates agency, stakeholder, and legitimacy perspectives into a singular cohesive framework. Agency theory underscores the significance of monitoring mechanisms, such as audit committees and auditor independence, to align the interests of managers and owners (Daily et al., 2003; Velte, 2023). Conversely, stakeholder and legitimacy theories indicate organisations ought to adopt broader governance measures, including enhanced non-financial disclosures and oversight, to meet societal expectations (Cho & Patten, 2007; Eugster et al., 2024; Freeman, 2010). By examining both traditional and innovative audit mechanisms collectively, this paper provides a more comprehensive explanation of fraud deterrence compared to previous literature. The incorporation of these perspectives significantly enhances the understanding of how diverse auditing mechanisms may effectively deter fraudulent activities in alignment with varying motivations and circumstances. Second, methodologically, we contribute to the literature by adopting a multifaceted empirical approach that enhances the reliability and robustness of the findings through complementary estimation techniques and a theoretically grounded predictive proxy for fraud risk. Third, this study is empirically significant as it encompasses various audit mechanisms from multiple European countries during a period of significant regulatory reforms. In contrast to prior studies that predominantly concentrate on a singular nation or sector, this pan-European, cross-industry methodology improves generalisability and underscores the diversity of governance systems within the European Union. This broad scope enables the identification of patterns that may be overlooked in limited or single-country analyses. Finally, the findings have clear practical implications. By highlighting the audit committee features, auditor practices, and CSR-audit arrangements that most effectively mitigate the risk of fraud, the findings provide valuable insights for regulators and boardrooms in establishing robust oversight. For example, this analysis could assist policymakers in developing auditing standards, such as those related to committee expertise or mandatory CSR audits, and aid firms in enhancing their internal controls to prevent fraud.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical framework, reviews the literature, and formulates hypotheses regarding the influence of audit characteristics on fraud risk. Section 3 details the research design, data sources, variable measurement, and the construction of empirical models. Section 4 presents the empirical results and robustness checks, while Section 5 discusses key findings and highlights policy implications. Lastly, Section 6 concludes with an examination of limitations and suggests directions for future research.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis formulationEvolving perspectives on fraud risk governance: integrating agency, stakeholder, and legitimacy theoriesThe discussion regarding audits, ESG, and CSR, along with their impact on fraud risk, mostly relies on theoretical frameworks such as agency theory, legitimacy theory, and stakeholder theory. Agency theory represents the classical perspective on this relationship, explaining the existence of public corporations based on the premise that managers act out of self-interest and do not fully face the consequences of their actions (Daily et al., 2003). An agency relationship is formed through a contract where one or more individuals (the principal(s)) employ another (the agent) to provide services on their behalf, thereby delegating some decision-making power (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Agency costs include the principal's monitoring expenses, the agent's bonding costs, and any residual losses (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Without proper oversight, managers might operate contrary to shareholder interests (Diwan & Sreeraman, 2024). The principal can reduce these misalignments by establishing effective incentives for the agent and investing in monitoring costs (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Agency theory posits that corporate governance reduces information disparities to prevent financial malpractice, assuring shareholders that managers align with their goals (Daily et al., 2003; Velte, 2023). Internal governance instruments, such as compensation structures and board composition, greatly impact the potential for development (Li et al., 2022). Audit quality, previously assessed primarily based on financial compliance, has now become a key component of governance frameworks that promote transparency and foster innovation (Zuo & Lin, 2022). High-quality audit oversight strengthens financial reporting and risk management, improving the clarity and reliability of data (Meqbel et al., 2024; Velte, 2023). This facilitates better decision-making and strategic planning for innovation, while preventing earnings manipulation and protecting shareholder interests (Meqbel et al., 2024; Yunis et al., 2024).

While agency theory focuses on the economic motives for oversight, legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory further broaden this perspective by acknowledging that organisations also pursue societal approval (Cho & Patten, 2007; Eugster et al., 2024; Freeman, 2010). Stakeholder theory asserts that companies aim to create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders, meaning any group or individual that affects or is affected by the business goals (Freeman, 1984). Consequently, managers must recognise influential entities and understand that the significance of stakeholders can change, requiring different levels of attention (Mitchell et al., 1997). Organisations must extend beyond simple compliance to promote ethical transparency by employing tools such as sustainability reports, which are crucial for displaying ESG performance and improving communication with stakeholders (Greco et al., 2015; Narváez-Castillo et al., 2024). Being responsive to stakeholders entails both proactive and reactive approaches to managing risks and opportunities (Laplume et al., 2008). Within this framework, internal audits and CSR assurance are regarded as essential signals for stakeholders, adapting to changing expectations and reputational risks (Eugster et al., 2024). Sound stakeholder governance recognises the ever-shifting landscape of relevance and institutional demands (Greco et al., 2015). Moreover, ESG scores enhance the accuracy of target prices, with firms that excel in ESG performance exhibiting fewer forecast errors (Umar et al., 2022).

Concerns exist in the literature that sustainability reporting often serves as a tool for marketing rather than genuinely informing stakeholders and improving sustainability practices (Aras & Crowther, 2009; Greco et al., 2015). This conflict relates to legitimacy theory, which explains why organisations disclose social and environmental information (Greco et al., 2015). Therefore, stakeholder theory must consider power, urgency, and legitimacy as organisations that adopt inclusive strategies are more likely to uphold their credibility (L’Abate et al., 2025; Mitchell et al., 1997; Moeremans & Dooms, 2021). Legitimacy refers to the perception that an entity's actions align with accepted social norms and values, shifting the focus from mere monitoring to maintaining an ethical corporate image (Cho & Patten, 2007; Hussain et al., 2025; Janang et al., 2020; Suchman, 1995). According to legitimacy theory, disclosure can improve stakeholder awareness and influence perceptions, with strategic disclosures aimed at building a more legitimate image, addressing concerns, and protecting confidential information (Michelon et al., 2015). Consequently, corporate governance practices like audits are not only utilized for control but also serve to project a responsible image and promote sustainable development (Achim et al., 2023; Michelon et al., 2015). Legitimacy strategies are particularly prevalent in industries facing public scrutiny (Cho & Patten, 2007; Darrell & Schwartz, 1997). Institutional legitimacy frequently involves aligning reports with stakeholder expectations, regardless of actual performance. Consequently, disclosures intended to promote legitimacy often accentuate positive outcomes while minimizing weaknesses (Cho & Patten, 2007; Michelon et al., 2015). Given this, auditing has transformed and must include the essential expertise and guidance for precise ESG risk evaluations and fraud detection (Eugster et al., 2024; Narváez-Castillo et al., 2024).

Traditional audit mechanisms and agency-based fraud risk preventionThe audit committee serves as a representative body of the board of directors and is mainly responsible for safeguarding and advancing the interests of shareholders (Bedard et al., 2004; Klein, 2002). Its main tasks include overseeing the accuracy of financial reporting, enhancing risk management, offering guidance, and making recommendations on matters related to the control of the entity’s activities (Almarayeh et al., 2022; Romano & Guerrini, 2012). Agency theory views the audit committee as a crucial mechanism for monitoring managers’ actions and ensuring the company provides reliable and relevant information to both shareholders and stakeholders (Alves, 2013; Alzoubi, 2019). By doing so, the audit committee plays a vital role in minimizing information manipulation and reducing information asymmetries between corporate insiders and outsiders, making its role essential for addressing agency problems that arise from corporate fraud (Alves, 2013; Alzoubi, 2019; Chen et al., 2008; Dey, 2008; Sarens et al., 2009). Prior empirical research highlights that the presence of an audit committee is associated with reduced fraudulent activities within organisations (Alzoubi, 2019; Baxter & Cotter, 2009; Piot & Janin, 2007). This effect is more robust in companies that implement an internal audit department and have an effective external audit (Alves, 2013; Alzoubi, 2019).

However, simply forming an audit committee may not be sufficient to assure the reliability of a firm’s accounting and auditing process. This means that the effectiveness of the audit committee in mitigating fraud risk also relies on its composition and expertise (He & Yang, 2014). A financial expert on an audit committee is a professional with a comprehensive understanding of accounting principles and substantial experience in preparing, auditing, or evaluating complex financial statements (Iyer et al., 2013). This expertise is essential, as it allows them to effectively fulfil their oversight responsibilities, ensuring the trustworthiness and accuracy of the reported information (Chen & Zhang, 2014; Wan-Hussin et al., 2021). The rationale for including financial experts in the audit committee is to assist other members in understanding auditor judgments and to help discern the essence of disagreements between external auditors and management (Bilal et al., 2023). Therefore, higher financial expertise reduces conflicts between managers and external auditors while mitigating internal control weaknesses (Krishnan, 2004; Zhang et al., 2007). For these reasons, agency theory emphasizes the importance of including financial experts on audit committees to mitigate agency conflicts and prevent fraudulent behaviour (Dhaliwal et al., 2010). Indeed, their specialized expertise enhances the understanding of financial and accounting matters, resulting in more accurate and effective audits of financial statements (Jamil & Nelson, 2011). From an empirical perspective, different studies support the theory that financial or accounting expertise enhances the credibility of financial reporting (Baxter & Cotter, 2009; Chen & Zhang, 2014; He & Yang, 2014). Other studies only partially support this assumption, suggesting that the performance of financial expert auditors is also influenced by additional factors such as gender (Zalata et al., 2018) and independence (Sultana & Van der Zahn, 2015).

Another important characteristic considered in traditional literature is the fees paid to auditors. Audit fees represent the costs incurred by a company to compensate an accounting firm for services rendered, specifically to audit the company’s financial statements and ensure they accurately and fairly reflect its financial position and performance (Kaituko et al., 2023; Rusmanto & Waworuntu, 2015). A substantial body of literature suggests that there is a positive relationship between audit fees and corporate fraud (Feldmann et al., 2009; Gul et al., 2003; Hogan & Wilkins, 2008; Hribar et al., 2014). Empirical evidence indicates that auditors adjust the nature, extent, and timing of their audit procedures based on evaluated fraud risk, highlighting several reasons for this (Lee & Ha, 2021; Mock & Turner, 2005). When auditors identify a significant audit risk, they are required to adjust their procedures to gather more evidence, which leads to an increase in planned audit hours and consequently results in higher audit costs that are transferred to the client in the form of elevated fees (Feldmann et al., 2009). In other words, high audit fees may result from a significant level of client-related risk, which balances out the increased demand (Cobbin, 2002; Kaituko et al., 2023). Moreover, heightened worries about reporting quality could elevate premium risks for auditors, as they may encounter substantial reputation damage and legal expenses if their clients' financial statements are found to be inaccurate (Hribar et al., 2014; Palmrose, 1988; Thompson & McCoy, 2008). In other words, to address concerns about inadequate accounting quality, auditors may increase the risk premium, resulting in higher fees or incurring additional expenses from potential legal action (Kaituko et al., 2023). Furthermore, auditors exhibit greater professional scepticism when the risk of fraud is elevated. This leads to greater scrutiny and higher fees as auditors perform a more thorough examination of the client's financial statements and internal controls, remaining vigilant against possible deceptive practices that might compromise the integrity of the financial reporting process (Lee & Ha, 2021; Payne & Ramsay, 2005). Finally, examining the issue through the lens of agency theory reveals that information asymmetry can be linked to diminished independence of the auditor caused by the higher fees. Specifically, as financial pressure intensifies, audit firms are more inclined to accommodate client requests. Consequently, rising audit fees could threaten the perceived independence of auditors, leading investors to view the firm’s financial statements as less reliable (DeAngelo, 1981; Kaituko et al., 2023; Magee & Tseng, 1990).

Therefore, based on theoretical arguments and prior empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are posited:

H1: There is a negative relationship between the presence of an audit committee and fraud risk.

H2: There is a negative relationship between audit committee financial expertise and fraud risk.

H3: There is a positive relationship between audit fees and fraud risk.

Innovative audit characteristics and stakeholder legitimacy governance approaches for fraud risk preventionIn the contemporary corporate landscape focused on reputation, sustainability, ESG frameworks, and CSR initiatives, traditional audit mechanisms must be complemented by more innovative approaches. Specifically, audit firm rotation, internal audit department reporting structures, and external auditing of non-financial reporting are increasingly relevant.

Beginning with auditor rotation, which entails both the required rotation of audit firms and the compulsory rotation of audit partners, this practice has become a crucial regulatory measure aimed at maintaining auditor independence and improving audit quality by regularly changing auditors' responsibilities (Florio, 2024). Various global jurisdictions mandate auditor rotation, such as the EU’s 2014 reforms that require ten-year rotation—extendable under joint audits or competitive re-tendering (Quick & Schmidt, 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). These measures address regulatory concerns that lengthy auditor tenures could create undue familiarity with clients, potentially diminishing professional scepticism and increasing the risk of financial statement fraud (Khaksar et al., 2022). Legitimacy theory supports the introduction of auditor rotation, emphasizing that organisational practices, such as audit governance structures, must continuously adapt to fulfil societal expectations and maintain legitimacy (Deephouse & Carter, 2005; Michelon et al., 2015; Suchman, 1995). From this theoretical standpoint, auditor rotation serves not just as a compliance tool but also as a crucial signal of an organisation's commitment to independent oversight, transparency, and ethical financial reporting. By requiring regular changes of audit firms or partners, organisations take proactive steps to address stakeholder worries about auditor objectivity, thus reducing concerns of collusion and demonstrating integrity to the market (Jackson et al., 2008; Tepalagul & Lin, 2015). Empirical and theoretical evidence consistently indicates that auditor rotation effectively decreases the risk of fraud. With a fresh perspective, a new auditor, free from long-term relationships, examines the client's financial documents with increased scepticism, enhancing the chances of identifying significant misstatements and deceptive accounting methods (Chi et al., 2009; Ghosh & Moon, 2005; Lin & Yen, 2022; Widyaningsih et al., 2019). Proponents of this perspective argue that regular turnover of auditors disrupts potentially problematic auditor-client relationships, maintains professional scepticism, and upholds rigorous audit procedures, thereby functioning as a deterrent against opportunistic managerial conduct (Karami et al., 2017; Khaksar et al., 2022; Mukhlasin, 2018; Widyaningsih et al., 2019).

Moving on to internal audit, it is defined as an objective assurance function established within organisations to evaluate and enhance risk management, control, and governance processes (Ahmed et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2011; Norman et al., 2010; Vadasi et al., 2019). To maintain its autonomy from management influence, best-practice guidelines and corporate governance codes suggest that the internal audit function should report to the audit committee (Eulerich et al., 2017; Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), 2002; Norman et al., 2010; Roussy et al., 2020; Vadasi et al., 2021). The interactions among the audit committee, its chair, the chief executive officer, and other managers significantly influence the effectiveness of internal audit (Roussy et al., 2020; Vadasi et al., 2019). When an internal audit department directly reports to an independent audit committee, the objectivity and authority of internal auditors are enhanced. This structure ensures that key findings regarding governance and controls can be conveyed without distortion from management (Arena & Azzone, 2009; Norman et al., 2010). Stakeholder theory, in a corporate governance context, implies that oversight mechanisms like the audit committee and internal audit should function in ways that protect the rights and information needs of various stakeholder groups (Roussy et al., 2020). Stakeholders like investors, regulators, and employees trust governance processes more when internal auditors report to an independent committee rather than directly to management. This approach meets demands for transparency and accountability by escalating significant risks and control issues to high-level oversight (Vadasi et al., 2019). From a legitimacy theory perspective, establishing a strong internal audit reporting line to the audit committee addresses public and regulatory demands for effective governance, thereby enhancing organisational legitimacy (Eulerich et al., 2017). By empowering internal audits through direct reporting to an independent audit committee, companies align with accepted governance norms and strengthen their credibility with stakeholders and regulators (Lenz & Hahn, 2015). Previous research supports these theoretical claims with empirical data (Abbott et al., 2010; Ahmed et al., 2021; Prawitt et al., 2009). Organisations in which the internal audit function reports directly to the audit committee typically deliver more effective internal audits and stronger internal controls. This is because the audit committee’s support and supervision enable internal auditors to operate independently and tackle issues swiftly (Abbott et al., 2010; Arena & Azzone, 2009). Additionally, studies indicate that this reporting structure may enhance organisational transparency, as findings and recommendations from internal audits receive board-level attention, thereby improving information quality and decreasing the likelihood of financial statement manipulation (Abbott et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2011; Prawitt et al., 2009).

The final variable under investigation is the external auditing of non-financial reporting. Non-financial reporting, often referred to as sustainability reporting, assesses and evaluates an organisation's performance regarding sustainable development for stakeholders (Boiral et al., 2019). In recent years, this type of reporting has become more significant as companies embrace social and environmental accountability practices to not only inform but also satisfy growing stakeholder expectations (Mion & Adaui, 2020). According to stakeholder and legitimacy theories, companies aim to align with societal values and fulfil stakeholder expectations to uphold their reputation and display appropriate behaviour that aligns with society's expectations (Braam et al., 2016; Deegan, 2002; Elaigwu et al., 2024; Karaman et al., 2021; Suchman, 1995). To resolve credibility issues, companies are increasingly utilizing external audits of non-financial reports to provide independent assurance of sustainability disclosures and improve the reliability of the information (Boiral et al., 2019; Park & Brorson, 2005). Transparent sustainability disclosures, particularly when validated, help companies address stakeholders’ information needs, build trust, and gain support (Elaigwu et al., 2024; Lock & Seele, 2016). Moreover, this alignment of societal and business interests enhances legitimacy (Ballou et al., 2018; Braam et al., 2016; Elaigwu et al., 2024; Karaman et al., 2021). Numerous studies show that external assurance of non-financial reporting improves financial quality and reduces fraud risk. This external assurance increases the reliability of non-financial data, minimizes managerial bias, improves stakeholders' perception, enhances credibility, and reduces the risk of manipulation (Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023; Ballou et al., 2018; Casey & Grenier, 2015). In addition, external financial auditors are increasingly concentrating on clients’ ESG practices and non-financial disclosures to evaluate the risk of material misstatement. When faced with heightened ESG risks or negative sustainability information, they intensify their audit efforts and scepticism, leading to a more thorough analysis of financial reporting (Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023; Baxter et al., 2013). From a management perspective, engaging in sustainability reporting demonstrates a commitment to transparency and management integrity, discouraging aggressive earnings management or fraud (Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023; Kim et al., 2012). To summarize, external verification of non-financial reporting strengthens trust and accountability by improving sustainability reports, legitimizing corporate actions, and signalling against fraud and earnings manipulation (Ballou et al., 2018; Simnett et al., 2009).

Consequently, drawing on theoretical arguments and existing empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: There is a negative relationship between auditor rotation frequency and fraud risk.

H5: There is a negative relationship between the internal audit department reporting to the audit committee and fraud risk.

H6: There is a negative relationship between external auditing of non-financial reporting and fraud risk.

Research methodologySampling and data collectionThe primary objective of this study is to examine the influence of various audit mechanisms on fraud risk. For this purpose, a sample of 1025 non-financial firms located in European Union member states during the period from 2018 to 2023 was considered. This timeframe is relevant due to significant regulatory reforms and the economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic during this period. The initial sample comprised 7387 firms listed in the Refinitiv Eikon database. Consistent with earlier research (Almarayeh et al., 2020; Chen & Zhang, 2014; Duong Thi, 2023; Tran et al., 2023), financial firms were excluded due to their unique accounting regulations and governance practices. Subsequently, a screening was performed to ensure the completeness of the financial disclosures necessary for calculating the Beneish M-Score and the associated suite of control variables, resulting in a reduction of the sample to 3707 companies. A final screening conducted by EViews software, which eliminated observations with missing or unreliable data, led to an unbalanced dataset of 1025 firms (Model 1: 1021; Model 2: 1021; Model 3: 648; Model 4: 1025; Model 5: 838; Model 6: 713).

Variables measurementThe dependent variable of this study is fraud risk (FRAUDRISK), as measured by the Beneish M-Score (Beneish, 1999). The Beneish M-score serves as a composite index derived from eight financial ratios that are appropriately weighted and combined to detect potential earnings manipulation. The complete calculation method for the score is detailed in Appendix. Higher M-Score values indicate a greater likelihood of financial statement manipulation, signalling higher fraud risk. Beneish’s initial model suggests that companies with an M-Score over –2.22 are probably engaged in fraudulent reporting. For the statistical analysis, we calculated each firm’s M-Score, which was then winsorized to limit extreme values and standardized for comparability across firms and models. Thus, the dependent variable FRAUDRISK is expressed as a continuous measure, with higher values indicating increased fraud risk.

Six independent variables capture key audit characteristics influencing fraud. Audit committee existence (AC) is a binary indicator reflecting whether a formal subcommittee oversees financial reporting and audits. The financial expertise of the audit committee (ACEXP) is assessed as a binary variable that receives a value of 1 if the committee includes at least three members, with at least one of those members having professional financial expertise and 0 if this condition is not met. Both governance variables are dichotomous and not transformed for analysis. Audit fees represent the total compensation paid to the external auditor for the annual financial statement audit, reflecting the complexity and effort required, as disclosed in the firm’s financial statements. To address the skewness in audit fees, we utilize a logarithmic transformation. Auditor rotation (AROT) is defined as a binary measure that indicates compliance with the EU’s 20-year maximum limit on statutory auditor tenure. AROT is assigned a value of 1 if the current audit firm has been engaged for less than 20 consecutive years, signifying regular rotation, and a value of 0 if the tenure exceeds 20 years, implying non-compliance with the regulatory standard. By presenting auditor rotation in this binary format, the study emphasizes whether a firm adheres to the established limit rather than the length of the tenure. The variable internal audit reporting line (INTAUDREP) is a binary indicator that shows if the internal audit department reports functionally to the audit committee. This binary measure does not require transformation. Finally, non-financial reporting external audit (NFREA) is a dummy variable set to 1 if a firm’s non-financial disclosures are audited by an independent party and 0 if not. This variable is used in the analysis without transformation.

Alongside the main independent variables, three control variables were included in the analysis to consider additional factors that may affect fraud risk: board size (BSIZE), firm size (FSIZE), and COVID. The size of the board, measured as the total number of directors, reflects the company's corporate governance capabilities. Many studies observed that larger boards are more effective in their oversight role (Alareeni, 2018; Orazalin, 2020; Quoc Thinh & Tan, 2019; Saona et al., 2020) and are associated with lower occurrence of fraudulent activities. This is because larger boards benefit from a wider range of competencies and expertise, enhancing the effectiveness of management oversight in the interest of shareholders and other stakeholders while also alleviating workload challenges (Orazalin, 2020; Peasnell et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2003). A limited number of studies have suggested that smaller boards better undertake their controlling functions in organisations. This assertion is grounded in the belief that smaller boards need less time to make decisions, which leads to improved communication as fewer individuals are involved (Abdou et al., 2021; Jensen, 1993). No transformation is applied to BSIZE, as its distribution is not extremely skewed in the sample. Firm size is also taken into account, as smaller and larger firms may exhibit different fraud dynamics. Previous research has highlighted a relationship between firm size and corporate fraud measured through discretionary accruals (Johnson et al., 2002). There are two contrasting views on the impact of the firm's size on corporate fraud. On the one hand, there is empirical evidence that larger firms are more likely to manipulate earnings in order to meet market expectations (Almarayeh et al., 2020; Jeong & Rho, 2004; Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). On the other hand, other studies argue that larger companies undergo closer scrutiny by investors and analysts, making them less prone to engage in corporate fraud practices (Ahmad-Zaluki & Wan-Hussin, 2010; Alves, 2013; Xie et al., 2003). This paper uses the natural logarithm of total assets as a measure of firm size. The last control variable is a COVID-19 (COVID) period dummy, which captures the distinctive context of the global pandemic. It is set to 1 for the fiscal years 2020 to 2022, indicating the outbreak and peak disruption period, and 0 for all other years. The rationale for this control stems from the extraordinary financial pressures and auditing challenges introduced by the pandemic, which may impact fraud risk. Research indicates that the COVID-19 crisis has notably increased the risk of fraud in financial statements due to a combination of economic distress and disruptions caused by remote work arrangements (Chen & Zhai, 2023; Halteh & Tiwari, 2023; Tan et al., 2023). The COVID dummy is a straightforward binary indicator and is not transformed.

Finally, the analysis incorporates country and industry dummy variables to address the diversity in jurisdictions and sectors. The country dummies account for the legal, regulatory, and cultural variations among firms’ home jurisdictions, while the industry dummies reflect sector-specific norms, risk exposures, and reporting practices that could influence the likelihood of fraud. Dummy indicators were introduced incrementally across each specification. The broadest feasible set was maintained as long as its inclusion did not compromise model stability or lead to inflated parameter estimates. This inclusive yet disciplined approach mitigates omitted-variable bias while maintaining interpretability and robustness.

Data analysis and research models constructionTable 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the continuous and categorical variables utilized in the analysis. All variables are presented after transformation to guarantee appropriate modeling and interpretation, as considered in the regression analyses.

Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis.

When examining the first continuous variable, FRAUDRISK, companies exhibit a slightly negative median (–0.16). The range is wide, extending from –0.64 to 8.66, indicating the presence of a limited number of firms with exceptionally elevated manipulation risk even after truncation and scaling. The second continuous variable, AFEES, has a mean (median) of 9.38 (10.46), with a range from 0.00 to a maximum of 15.42. This data indicates significant variability in audit pricing. The third variable, BSIZE, indicates that boards have, on average, 9.37 directors (median = 9.00), with sizes ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 34, underscoring substantial heterogeneity in board composition across the sample. The last continuous variable, firm size (FSIZE), has a mean of 18.44 and a median of 18.21. Its range extends from 12.54 to 24.83, suggesting that while most firms are comparable in size, there remains considerable variation.

Moving on to categorical variables, the descriptive statistics show that 90.78% of the sampled companies have established an audit committee, while 9.2% have not. Moreover, aligning with regulatory focus on expertise, 63.79% of audit committees include at least one financial expert (ACEXP), while 36.2% lack this expertise. Regarding internal audit reporting (INTAUDREP), 87.80% of firm-years reveal that internal auditors report directly to the board’s audit committee, in contrast to 12.2% who do not. Furthermore, external assurance for non-financial disclosures (NFREA) is observed in 88.45% of instances. Lastly, the panel is evenly divided between pre-pandemic and pandemic subsamples, providing balanced exposure to COVID-19-related shocks.

Following the transformation and description of the variables utilized for statistical analysis, two complementary diagnostic tools were employed to evaluate potential multicollinearity issues among the independent variables: the Pearson correlation matrix (Table 2) and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis (Table 3).

Pearson correlation matrix.

Note: Statistical significance levels are represented as follows: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01.

Variance inflation factor analysis.

The Pearson correlation matrix examines bivariate linear relationships between each pair of variables, providing an initial screening to detect strong correlations that might suggest redundancy. Correlations exceeding 0.80 typically raise concerns regarding multicollinearity. In this study, the matrix revealed that the correlations between independent variables are generally low to moderate, indicating no severe multicollinearity. Significant correlations (denoted by *, **, or ***) exist among some variables, but their magnitudes remain below critical thresholds. Regarding the relationship between the dependent variable FRAUDRISK and the independent variables, FRAUDRISK exhibits weak negative correlations with most governance variables, suggesting that stronger audit mechanisms may be modestly associated with lower fraud risk. The correlation between FRAUDRISK and COVID is positive (0.024) and significant, albeit very weak, which may reflect slightly elevated fraud risks during the COVID-19 period due to operational disruptions and weakened controls. All correlations between FRAUDRISK and predictors are low, supporting the appropriateness of including these variables in the analysis without concerns of high redundancy.

Despite reassuring correlation matrix results, a VIF analysis was conducted to rigorously verify the absence of multicollinearity among multiple variables. Multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed by calculating Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) from an initial ordinary least squares (OLS) model. The VIF serves as a metric that quantifies the extent to which the variance of an estimated regression coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity with all other explanatory variables. VIF values exceeding 5 indicate moderate multicollinearity, whereas values surpassing 10 raise significant concerns regarding severe multicollinearity. As documented in Table 3, all VIF values range from 1.009 to 1.723, remaining well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, thereby indicating the absence of severe multicollinearity among the explanatory variables (Hair et al., 2010). Thus, based on the correlation analysis, no serious multicollinearity issues were detected, and all variables were retained for subsequent analysis.

To evaluate the presence of heteroskedasticity across all model specifications, the Breusch-Pagan test was conducted. As a general rule, for results based on the Breusch-Pagan test, a p-value below 0.05 indicates rejection of the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity, suggesting the presence of heteroskedasticity. As reported in Table 4, the results indicate that heteroskedasticity is present in Models 1 (p = 0.002), 2 (p = 0.029), 4 (p = 0.002), and 5 (p = 0.021), as their p-values fall below the 0.05 significance threshold. In contrast, Models 3 (p = 0.654) and 6 (p = 0.677) do not provide significant evidence of heteroskedasticity. Since most of the estimated models show heteroskedasticity, the assumptions of OLS are violated. The EGLS method was implemented to obtain efficient and reliable coefficient estimates across all models. By correcting for heteroskedasticity, EGLS enhances the precision of standard errors and strengthens the validity of the inferential results. To ensure consistency and comparability in results, the EGLS method was used for all model estimations. Additionally, to address possible contemporaneous correlation among cross-sectional units, we applied cross-section weights and period weights (PCSE-corrected standard errors and covariances, d.f. adjusted). These modifications guarantee robust standard errors, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of the regression estimates.

Breusch-Pagan test.

Based on this methodological framework, the following regression models were estimated:

Model 1:

Model 2:

Model 3:

Model 4:

Model 5:

Model 6:

Where:

- -

FRAUDRISK is the dependent variable measuring fraud risk;

- -

AC is the independent variable reflecting the presence of an Audit Committee;

- -

ACEXP is the independent variable representing Audit Committee Financial Expertise;

- -

AFEES is the independent variable Audit Fees;

- -

AROT is the independent variable Audit Rotation;

- -

INTAUDREP is the independent variable that indicates the Internal Audit Department's reporting line to the Audit Committee;

- -

NFREA is the independent variable that refers to external assurance of non-financial reporting (CSR/H&S/Sustainability);

- -

COVID is the control variable indicating the COVID-19 period;

- -

BSIZE is the control variable board size;

- -

FSIZE is the control variable firm size;

- -

ΣCOUNTRY_EFFECTS refers to country dummy variables considered to control for country-specific heterogeneity;

- -

ΣINDUSTRY_EFFECTS refers to industry dummy variables considered to control for industry-specific heterogeneity;

- -

ε is the error term.

Table 5 presents the results of the EGLS models that examine the influence of various audit-related characteristics on fraud risk. Six separate models are estimated, each focusing on a distinct audit mechanism while controlling for board size, firm size, the COVID-19 crisis, industry-specific effects, and country-level differences. In all models, the dependent variable is fraud risk, while the independent variables comprise traditional audit mechanisms—specifically, the existence of an audit committee (AC), audit committee financial expertise (ACEXP), and audit fees (AFEES)—as well as innovative audit practices, which consist of auditor rotation (AROT), internal audit reporting line (INTAUDREP), and external auditing of non-financial reports (NFREA).

Main results investigating the influence of audit mechanisms on fraud risk.

Note: Statistical significance levels are represented as follows: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01. T-statistics are in parentheses.

The models show consistently significant relationships between audit structures and fraud risk, highlighting the pivotal role of governance practices in mitigating fraudulent behaviour. The R-squared values range between 21% and 45%, indicating that the models explain a moderate proportion of the variance in fraud risk. The F-statistics for all models are highly significant (p-value = 0.000), confirming that the models as a whole are statistically meaningful and that the sets of variables jointly explain fraud risk. The Durbin-Watson statistics are close to 2 in all models (ranging from 1.544 to 1.724), suggesting no severe autocorrelation problem in the residuals. The VIFs for all independent variables remain below 2.25, far below the conventional threshold of 10, indicating that multicollinearity is not a concern in the models and that the estimated coefficients are reliable.

Model 1 considered the existence of the audit committee (AC) as the independent variable. The results indicate that the existence of an audit committee (AC) has a negative and statistically significant impact on fraud risk at the 1% significance level, confirming the first hypothesis (H1). In other words, the presence of the audit committee is associated with a reduction in fraud risk. Specifically, when a company possesses an audit committee, the fraud risk is diminished by approximately 0.033 units. In relation to the control variables, COVID demonstrates a positive and statistically significant effect (at the 1% level) on fraud risk, indicating that during periods of crisis, companies are more inclined to engage in fraudulent behaviours. Furthermore, board size and firm size both exhibit negative and statistically significant associations with fraud risk, indicating that larger boards and firms are linked to lower levels of fraud risk, likely due to improved monitoring mechanisms.

Model 2 examined how the financial expertise of the audit committee (ACEXP) impacts fraud risk. The coefficient for ACEXP is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that having audit committee members with financial knowledge lowers fraud risk, as anticipated in the second hypothesis (H2). Specifically, an increase in financial expertise is associated with a reduction in fraud risk of about 0.005 units. Concerning the control variables, COVID continues to exert a positive and statistically significant impact on fraud, while both BSIZE and FSIZE consistently exhibit negative and significant effects. This suggests that larger boards and companies are less prone to fraud in this model as well.

Model 3 explored the relationship between audit fees (AFEES) and fraud risk. The results show a positive and statistically significant coefficient for audit fees at the 1% level. A 1-unit increase in log-transformed audit fees is associated with a 0.002 unit increase in fraud risk. This outcome aligns with the third hypothesis (H3) and indicates that higher audit fees correspond with elevated fraud risk, underscoring auditors’ need for more rigorous procedures and risk‐based pricing when misstatement risk is high. COVID still shows a strong positive correlation with fraud risk, whereas BSIZE continues to be negatively linked to fraud risk, aligning with earlier models. In this model, FSIZE shows no significant impact of FRAUDRISK.

Model 4 introduced auditor rotation (AROT) as the key independent variable. The findings reveal a negative and statistically significant relationship at the 1% level, indicating that regular auditor rotation is associated with lower fraud risk, as outlined in the fourth hypothesis (H4). Specifically, a one-unit increase in auditor rotation variable decreases fraud risk by approximately 0.024 units. The COVID indicator once again exhibits a positive correlation with fraud risk, whereas an increased board size and larger firms remain significantly linked to lower fraud risk.

Model 5 evaluated the effect of the internal audit reporting line (INTAUDREP) on fraud risk. The results show that INTAUDREP has a negative and statistically significant effect at the 1% level on FRAUDRISK, validating the fifth hypothesis 5 (H5). Firms, where internal audit departments report directly to the audit committee, experience a reduction in fraud risk of approximately 0.011 units. The control variables maintain their consistent behaviour: COVID positively influences fraud risk, while increased BSIZE negatively and significantly reduces it. Firm size (FSIZE) continues to be negatively associated with fraud.

Finally, Model 6 focused on the external auditing of non-financial reports (NFREA). The findings confirm the sixth hypothesis (H6) and indicate a negative and statistically significant relationship at the 1% level. Hiring an external auditor for non-financial reports decreases the risk of fraud by about 0.008 units. The impact of COVID persists as a major factor driving fraud risk positively. Larger boards are still found to have a considerable negative effect on fraud. In this analysis, the size of the firm (FSIZE) does not show a significant connection to fraud risk, indicating its role varies based on the specific audit practices implemented.

Robustness testsTo ensure the reliability and validity of the main findings, two complementary robustness checks were conducted.

First, a dynamic panel model was estimated utilizing the GMM with a lagged dependent variable method to address possible endogeneity issues. In particular, the Arellano-Bond estimator in first differences with robust standard errors was applied. The GMM results from the six models (Model 7-Model 12) are presented in Table 6 and consistently support the key findings. Specifically, the presence of the audit committee (AC), audit committee financial expertise (ACEXP), auditor rotation (AROT), internal audit reporting line (INTAUDREP), and the external audit of non-financial reports (NFREA) all show negative and statistically significant impacts on fraud risk. Furthermore, consistent with the main findings, audit fees (AFEES) demonstrate a positive and statistically significant correlation with the risk of fraud. Regarding control variables, COVID consistently demonstrates a positive and significant relationship with fraud risk, while larger boards (BSIZE) generally mitigate fraud risk across models, with the exception of models 8, 9 and 11, where it shows no significance. In this instance, there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between firm size (FSIZE) and fraud risk, likely reflecting complexity effects observed in larger firms, with the exception of Model 10, where it shows no significance. Diagnostic tests validate the dynamic panel model. The Hansen J-test p-values exceed conventional significance thresholds across all models, thereby affirming the validity of the instrument sets and the absence of overidentification issues. Furthermore, the Arellano-Bond AR(1) tests indicate anticipated first-order serial correlation (p < 0.05), whereas the AR(2) tests yield non-significant results (p > 0.1), thereby confirming the absence of second-order autocorrelation. All audit characteristics validated their anticipated impact; thus, employing an alternative statistical method for the robustness analysis enhances the reliability of the main findings.

Results of GMM models investigating the influence of audit mechanisms on fraud.

Note: Statistical significance levels are represented as follows: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01. T-statistics are in parentheses.

Second, robustness was tested by employing an alternative measure of fraud risk (AFRAUDRISK): the 5-variable Beneish M-score (Corsi et al., 2015) instead of the standard 8-variable M-score. Panel EGLS regressions with cross-sectional weights were performed, resulting in 6 additional models (Model 13-Model 18) presented in Table 7. Consistent with the main results, the presence of an audit committee (AC), audit committee financial expertise (ACEXP), auditor rotation (AROT), internal audit reporting line (INTAUDREP), and external audit of non-financial reports (NFREA) all maintain negative and significant coefficients, while audit fees (AFEES) continue to show a positive, significant association with fraud risk. Regarding the control variables, COVID consistently maintains a positive and highly significant impact on fraud risk, while board size (BSIZE) and firm size (FSIZE) maintain strong negative relationships with fraud risk, in line with the main results, with exception for Model 14 and Model 16 that shows no significant relationship between board size and fraud risk. The models demonstrate moderate to strong explanatory power, with R-squared values between 17% and 48%. Furthermore, all F-statistics demonstrate strong significance (p < 0.01), confirming the overall validity of the model. The Durbin-Watson statistics range from 1.646 to 1.904, indicating no significant autocorrelation issues. The VIFs remain well below 3.5, mitigating concerns about multicollinearity.

Results of EGLS models investigating the influence of audit mechanisms on fraud with an alternative measure for the dependent variable.

Note: Statistical significance levels are represented as follows: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01. T-statistics are in parentheses.

No audit characteristic contradicted its expected direction, affirming the consistency of theoretical expectations. Thus, the robustness analysis utilizing an alternative fraud proxy enhances the reliability of the main findings and validates all of the study’s hypotheses.

DiscussionThe primary objective of this study is to examine the effect of audit characteristics on fraud risk. Empirical results reveal that both traditional agency-theoretic audit mechanisms and innovative stakeholder-oriented audit practices significantly impact corporate fraud risk.

Under agency theory, an audit committee acts as a monitoring tool that reduces information asymmetry between management and shareholders (Bedard et al., 2004; Klein, 2002). In line with this premise, this study found that companies that establish audit committees exhibit significantly lower fraud risk. This observation is consistent with previous evidence indicating that forming an audit committee enhances oversight of financial reporting and deters opportunistic misstatements (Alzoubi, 2019; Baxter & Cotter, 2009; Piot & Janin, 2007). With respect to the financial expertise of the audit committee, our empirical findings support theoretical claims suggesting that members with accounting or financial proficiency improve monitoring effectiveness (Chen & Zhang, 2014; Wan-Hussin et al., 2021). These experts can better analyse intricate financial data and question management’s accounting decisions, thus decreasing the potential for fraudulent reporting. Moreover, the results indicate that higher audit fees correlate with increased fraud risk, aligning with a risk-based pricing model where auditors demand higher fees for cases with a greater likelihood of misstatement (Cobbin, 2002; Kaituko et al., 2023). From an agency theory perspective, the payment of elevated fees may indicate the necessity for more comprehensive audit procedures rather than a guarantee of improved reporting quality. Overall, these findings demonstrate that traditional mechanisms help align the interests of managers and shareholders by strengthening financial statement oversight and reducing agency conflicts.

The findings regarding the innovative audit characteristics align well with stakeholder and legitimacy theory. Beginning with auditor rotation, the results indicate that firms with more frequent auditor changes experience a lower risk of fraud due to the introduction of new perspectives during the audit process. Our empirical findings support both theory and practice, suggesting that rotating auditors can mitigate the “familiarity threat” that arises from long-term auditor-client relationships (Chi et al., 2009; Ghosh & Moon, 2005; Jackson et al., 2008; Lin & Yen, 2022; Widyaningsih et al., 2019). Furthermore, when the internal audit function reports directly to the audit committee, fraud risk is notably decreased. An internal audit department that reports to the audit committee can bring issues to light without interference from management, which is in line with good governance and the expectations of stakeholders for ethical behaviour (Abbott et al., 2010; Ahmed et al., 2021; Prawitt et al., 2009; Roussy et al., 2020; Vadasi et al., 2021). Finally, our findings suggest that companies that choose to audit their non-financial data experience fewer reasons or opportunities to manipulate their financial statements. This indicates that validating CSR or sustainability metrics fosters a culture of accountability that positively impacts financial reporting (Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023; Ballou et al., 2018; Casey & Grenier, 2015).

Additionally, the control variables behaved as expected. Consistent with previous research, the results reveal that larger boards, suggestive of more diverse oversight, correlate with a reduced fraud risk (Alareeni, 2018; Orazalin, 2020; Quoc Thinh & Tan, 2019; Saona et al., 2020). In terms of firm size, the findings are mixed, reflecting the varied results found in the existing literature (Ahmad-Zaluki & Wan-Hussin, 2010; Almarayeh et al., 2020; Alves, 2013; Jeong & Rho, 2004). The COVID-19 dummy is significantly positive, indicating that the stress and uncertainty of the pandemic heightened the incentives or pressures to misreport, aligning with recent studies on corporate behaviour during crises (Chen & Zhai, 2023; Halteh & Tiwari, 2023; Tan et al., 2023).

Importantly, all key results remain robust across both EGLS and GMM estimations and when using an alternative measurement for the dependent variable, underscoring the reliability of the findings.

This study has clear implications for regulators and policymakers. Firstly, it reinforces the value of mandatory audit committee standards: requiring independent, financially literate committee members appears to improve financial reporting quality measurably. By enhancing the technical skills of oversight bodies, companies indicate to the market that they maintain strong management controls. For policymakers, this implies that promoting expertise within audit committees can boost confidence in corporate reporting. Secondly, this study's outcomes support policies regarding audit rotation by illustrating that it improves audit oversight and fraud deterrence, thereby strengthening the case for the imposition or reduction of mandatory rotation periods. For organisations, transparency concerning rotation schedules can also indicate a commitment to auditor independence and professional scepticism. Thirdly, the significance of independent internal audits indicates that governance codes should emphasize the significance of internal audit reporting lines and autonomy. Corporations should organise their internal audit frameworks to ensure that internal auditors have direct access to the audit committee, enabling them to report objectively. Regulatory guidelines frequently emphasize this structure as a best practice, and our evidence suggests that adherence to it can substantially mitigate the risk of fraud. Ultimately, the novel finding that external assurance on non-financial reports reduces fraud risk highlights a broader agenda: stakeholders and regulators seeking to combat fraud may encourage companies to voluntarily audit their non-financial reports. Managers should consider third-party assurance of non-financial disclosures as part of a more comprehensive integrity framework. Importantly, linking external CSR audits to fraud reduction indicates that ethical reporting is not an isolated effort: credibility in any corporate disclosure fosters trust across the entire enterprise.

In summary, the findings integrate agency theory with stakeholder and legitimacy theory by demonstrating that a comprehensive audit framework, which combines traditional financial oversight with broader accountability measures, can effectively mitigate the risk of fraud.

ConclusionThis study presents comprehensive evidence illustrating that key traditional audit elements, namely the establishment of an audit committee, the involvement of qualified financial experts, and the determination of reasonable audit fees, are crucial in significantly mitigating the risk of corporate fraud. Furthermore, the research underscores the importance of contemporary audit practices, including the regular rotation of auditors to provide fresh insights, independent reporting by internal auditors to enhance accountability, and the auditing of non-financial reports that address significant issues such as sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Collectively, these foundational and innovative strategies constitute a robust defence against fraudulent activities, fostering a culture of integrity within organisations. Thus, the findings confirm that the effective governance mechanisms described by agency theory, combined with thorough stakeholder-oriented assurance, work together to mitigate fraud risk.

This study contributes to both theory and practice. Theoretically, our findings enhance the literature by examining six audit characteristics in one study instead of just one or two. Additionally, this research integrates multiple governance perspectives, demonstrating that both traditional agency-focused audit interventions and newer legitimacy-driven practices are important for fraud detection. This suggests that corporate governance models should adapt to incorporate stakeholder and transparency aspects. This study identifies critical leverage points for both practitioners and policymakers. Specifically, enhancing the quality of audit functions and promoting innovative assurance services emerge as essential strategies for strengthening corporate integrity. Furthermore, the empirical findings provide support for regulatory initiatives, such as the requirement for financial expertise on audit committees and the limitation of auditor tenure, to enhance oversight and reduce the risk of fraud. Moreover, due to their effectiveness in curbing fraudulent activities, it is recommended to provide incentives for auditing non-financial reports. To sum up, the evidence suggests that strengthening internal governance and external assurance enhances financial reporting integrity and transparency. This paper highlights the need for governance strategies that address both shareholder oversight and broader stakeholder transparency demands.

Like all empirical research, this study has limitations that highlight opportunities for further investigation. Firstly, while the Beneish M-score is a common metric in fraud-risk studies, it serves as an indirect proxy and may not fully account for all types of manipulation or the qualitative dimensions of fraud. Secondly, the applicability of our findings may vary due to specific institutional contexts or temporal influences, such as the effects of COVID-19, within the sample. Future research could tackle these concerns by focusing on actual fraud cases or enforcement actions as dependent variables, analysing various countries or industries, and assessing the evolving nature of governance over time.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIsabella Lucuț Capraș: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Monica Violeta Achim: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Birjees Rahat: Visualization, Validation, Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis. Giuseppe Nicolò: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

The calculation of the variables that constitute the Beneish model is presented below (Beneish, 1999):

1. Days' sales in a receivable index (DSRI)

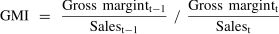

2. Gross margin index (GMI)

3. Asset quality index (AQI)

4. Sales growth index (SGI)

4. Depreciation index (DEPI)

5. Sales and general and administrative expenses index (SGAI)

6. Leverage index (LVGI)

7. Total accruals to total assets (TATA)

The Beneish M-Score is calculated using the following formula:

M=−4.84+0.92*DSRI+0.528*GMI+0.404*AQI+0.892*SGI+0.115*DEPI-0.172*SGAI+4.679*TATA-0.327*LVGI

The M-score has a threshold value of −2.22. Specifically, if the estimated score is below this threshold, a business is unlikely to be engaging in manipulation. Conversely, if the calculated manipulation score exceeds the threshold, it suggests the business is likely managing profits.