This study investigates the influence of national cultural values on innovation performance across European Union (EU) member states, applying Hofstede’s six-dimensional cultural model along with the 2024 Summary Innovation Index. Addressing major gaps in prior research—including the lack of EU-focused, longitudinal analyses and limited alignment between theoretical claims, and empirical testing—the study applies a two-stage design. In the first stage, multiple regression analysis identifies indulgence (IND) as a robust, statistically significant predictor of innovation performance, while individualism (IDV) gains significance only in a reduced model, despite extant literature. In the second stage, t-tests demonstrate that neither IND nor IDV significantly distinguishes countries that improved their innovation group ranking between 2017 and 2024. These findings indicate that while permissive and individualistic cultures are associated with higher baseline innovation capacity, they do not drive innovation advancement over time. Thus, cultural values represent important but not decisive structural elements within national innovation systems. Long-term progress appears to be more strongly shaped by other factors; for instance, institutional, political, and structural conditions. Consequently, innovation policies should be culturally informed rather than culturally determined—recognising the role of culture without overemphasising its influence.

Innovation has long been recognised as a fundamental driver of economic growth, technological advancement, and societal progress (Furman et al., 2002; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021). Numerous empirical studies have confirmed the positive relationship between research and development (R&D) investments and national productivity (Baumann & Kritikos, 2016; Dritsaki & Dritsaki, 2023; Zhang & Mohnen, 2022). Furthermore, several studies have highlighted that a country’s ability to innovate is also shaped by broader systemic factors, such as governance, culture, and openness, which interact closely with the National Innovation System (Fagerberg & Srholec, 2018; Freeman, 2008; Thoenig & Verdier, 2003). In the context of the European Union (EU), the European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS) has become a central instrument in benchmarking innovation capacity across member states, highlighting long-standing gaps between innovation leaders, strong innovators, moderate innovators, and modest innovators (European Commission, 2024). These differences in innovation performance are due to economic or institutional inputs, and increasingly warrant studies including less visible factors, such as cultural factors (Chaudhuri et al., 2022; Escandon-Barbosa et al., 2022; Jourdan & Smith, 2021).

The role of national culture in shaping innovation systems has gained significant attention over the past two decades. Tian et al.’s (2018) systematic review of the literature reveals significant impacts of organisational and national cultures on innovation, with various cultural dimensions that affect innovation differently. Scholars argue that cultural values influence how societies perceive change, risk-taking, collaboration, and creativity—all essential to innovation processes (Bhagat & Hofstede, 2002; Goncalo & Staw, 2006; Parveen et al., 2023; Shane, 1993). For instance, Hofstede’s widely adopted six-dimensional model of national culture—including power distance (PDI), individualism (IDV), masculinity (MAS), uncertainty avoidance (UAI), long-term orientation (LTO), and indulgence (IND)—provides a structured lens for examining cross-country differences in innovation-related behaviour (Cahyadi et al., 2024; Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2011; Schooler & Hofstede, 1983; Tihanyi et al., 2005). Countries that score high on dimensions like IDV and IND tend to support personal initiative and openness to new experiences, which are often associated with higher innovation outcomes (Kutan et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2018).While previous research has investigated how national culture correlates with innovation performance, most studies have focused on global samples or firm-level dynamics, often overlooking EU-specific dynamics and recent innovation data (Boubakri et al., 2021Prim et al., 2017). Furthermore, extant literature indicate that cultural effects are not uniform but may interact with governance systems, historical legacies, and policy environments (Bogers et al., 2018; Parveen et al., 2023; Verspagen, 2006).

As Shane (1993-59.p) noted, ‘Countries may not be able to increase their innovation rates simply by increasing the amount of money spent on research and development or industrial infrastructure. They may need to change the values of their citizens to those that encourage innovative activity’. Aligned with this assertion, a deeper sociological understanding is necessary to foster a greater performance of innovation. Despite the growing attention towards cultural underpinnings of innovation, several conceptual and empirical gaps remain unaddressed in existing literature (Tian et al., 2021). First, while numerous studies have explored the relationship between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and innovation performance across a number of countries (Bonetto et al., 2022; Boubakri et al., 2021; Khan & Cox, 2017), relatively few have focused exclusively on the EU. Considering the EU’s common policy framework despite considerable cultural heterogeneity, targeted studies within this region offer both relevance and comparability (Efrat, 2014).

Second, although the positive association between cultural values—such as IDV and IND—and innovation outcomes has been supported by several studies, these findings are primarily based on static data or cross-sectional analyses (López-Cabarcos et al, 2021; Yeganeh, 2023). To date, there is a lack of research examining whether cultural traits can actually explain performance improvements over time, such as upward movement in innovation rankings (Tekic & Tekic, 2021). As such, longitudinal and group-based empirical validation of these assumptions remains underdeveloped.

Third, most existing studies draw upon old or aggregated innovation data, limiting the timeliness of insights. This study addresses this gap by relying on the most recent data available from 2024 (European Commission, 2024), offering a more accurate and relevant illustration of the cultural–institutional relationship within EU innovation systems. By combining these updated innovation indicators with Hofstede’s national cultural dimensions, the analysis conducted in this study delivers a context-sensitive assessment of how culture influences innovation capacity (Kole, 2025). In light of these considerations, the current study seeks to reevaluate the cultural underpinnings of innovation in the EU using fresh data and comparative statistical techniques. Considering the EU’s ongoing pursuit of cohesion and balanced development, uncovering and including cultural factors that shape national innovation performance is both timely and of strategic policy interest. Accordingly, the current study investigates the influence of Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions on member states’ innovation output. It applies regression models to test for statistically significant relationships and supplements this with t-tests—comparing countries that advanced in their innovation classification between 2017 and 2024 to those that remained unchanged. The central argument of this research is that although IDV and IND are robustly and positively associated with innovation performance, these cultural traits alone do not account for movement between innovation performance groups. Therefore, countries with favourable cultural profiles in literature may still underperform in terms of innovation advancement. Accordingly, the study bridges theoretical insights on the cultural foundations of innovation with empirical validation based on updated European data. It offers a nuanced perspective that highlights both the enabling and limiting roles of national culture in shaping innovation outcomes, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of innovation systems in Europe.

To the authors knowledge, this is the first study to apply a longitudinal, two-stage empirical approach to assess the relationship between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and changes in innovation performance specifically within the EU context. By integrating updated EIS data with cross-country cultural metrics, this study delivers a context-sensitive and temporally grounded analysis of cultural influences on innovation outcomes. These insights extend existing literature that has largely focused on static or global datasets, offering methodological and empirical advancement. Beyond academic relevance, the findings bear direct implications for EU-level innovation policy. As EU seeks to reduce disparities between innovation leaders and laggards, understanding how deep-seated cultural traits interact with institutional frameworks can inform better tailored, more culturally-responsive innovation strategies, instead of relying on one-size-fits-all policy prescriptions.

The current study is structured in two stages. In the first stage, a comprehensive review of the literature is conducted to establish the theoretical link between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and national innovation performance. These conceptual claims are then empirically tested using the most recent dataset, and the results are compared with the findings from the literature. In the second stage, based on the indicators identified as significant in both the literature and statistical analysis, a comparative test is conducted. This analysis investigates whether the selected cultural dimensions have explanatory power when comparing EU countries that moved upward in innovation performance between 2017 and 2024 with those that did not. This two-stage approach offers a novel contribution to the literature by combining theoretical validation, empirical testing, and group comparison. Furthermore, it seeks to answer two central research questions:

Research questions and hypothesesThis study addresses the following main research question: RQ1: How do national cultural characteristics—particularly IDV and IND—affect innovation performance in EU member states? To answer this question, authors formulate and test the following hypotheses:

- •

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The level of IDV is positively and significantly associated with innovation performance as indicated by the Summary Innovation Index (SII) in EU countries.

- •

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The level of IND is positively and significantly associated with innovation performance as denoted by the SII in EU countries.

A complementary sub-question is also examined: RQ2: Do these cultural characteristics support improvements in innovation performance between 2017 and 2024? Correspondingly, authors propose two additional hypotheses:

- •

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Countries that improved their innovation performance group ranking between 2017 and 2024 demonstrate higher IDV scores than countries that did not.

- •

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Countries that improved their innovation performance group ranking between 2017 and 2024 demonstrate higher IND scores than countries that did not.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the existing literature and theoretical frameworks linking national culture to innovation performance, with particular emphasis on Hofstede’s dimensions. Section 3 delineates the research methodology, including the selection of data sources, the construction of regression models, and the application of t-tests to assess group-level differences. In Section 4, the empirical results are presented and interpreted in terms of the proposed hypotheses. Following this, Section 5 explores the broader implications of the findings, highlighting their relevance in both innovation policy and cultural analysis. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarising the key contributions of this study and outlining potential avenues for future research.

Literature reviewNational culture and innovation: a theoretical foundationNational culture has been long considered a contextual factor influencing economic behaviour, including innovation. Grounded in cross-cultural psychology and comparative management theories, scholars have argued that the values of innovation are increasingly recognised as influenced by not only technological infrastructure and economic policy but also deeper cultural values embedded in a society. While traditional innovation studies have emphasised factors such as R&D intensity, education, and market structure (Escandon-Barbosa et al., 2022; Furman et al., 2002; OECD, 2021), a growing body of research highlights that national culture can significantly shape a country’s capacity to innovate (Bhagat & Hofstede, 2002; Fagerberg & Srholec, 2018).

Innovation has been known to be associated with economic growth (Fagerberg & Srholec, 2018; Freeman, 2008; Thoenig & Verdier, 2003). Fagerberg and Srholec (2018) proved that innovation systems and governance are particularly important for economic development; furthermore, the authors strongly supported the notion that various factors associated with the national innovation system, such as governance quality, political system, and openness, interact significantly with the capacity for innovation. These indicators intersect with the cultural dimensions identified by Hofstede (Schooler & Hofstede, 1983). Other researchers, for example, Boubakri (Boubakri et al., 2021 concluded in their research that national culture exerts a significant influence on innovation. In addition, Herbig and Dunphy (1998) highlighted that existing cultural conditions play a crucial role in determining the adoption of new innovations, including the timing, manner, and form of adoption. They argued that a society’s values direct the trajectory of technological development, by either fostering or hindering it. Lundvall (2007) discovered that various national aspects can impact motivation to innovate at the national level. He emphasised the importance of redistributing power, building institutions, and enhancing the openness of innovation systems, particularly in developing countries. Culture has garnered increasing attention in the broader sphere of business and management in recent years as a factor that influences innovation. Its critical role in international management and organisational development and its contributions to business and economic development have been recognised by scholars such as Verspagen (2006) and Rohlfer and Zhang (2016). Many researchers have explored the relationship between culture and innovation in the business domain, as evidenced by studies conducted by Goncalo and Staw (2006) and Parveen et al. (2023). Evidently, some countries or enterprises within specific cultural contexts exhibit strong innovation capabilities, while others may not, highlighting the significance of cultural factors in innovation dynamics. Hofstede (1994) claimed that the larger the cultural gap between the home and the host countries, the more managers of multi-national enterprises (MNEs) need to reconsider the way they operate their cross-border operations. In their meta-analysis, Tihanyi et al. (2005) linked cultural aspects to innovation by concluding that cultural differences between countries have a negative impact on international diversification in high-technology industries. While MNEs’ operations are clearly impacted by the national culture of the host countries (Dwyer et al., 2005; Steensma & Lyles, 2000), evidence suggests a reciprocal relationship, as their internal processes and practices influence subsidiaries and eventually spread into local industries. Though this impact occurs at the micro-level, it is bound to resonate at the national level in the long run (Brock et al., 2000; Hofstede, 1994). A systematic review (Tian et al., 2018) of the literature reveals significant impacts of organisational and national cultures on innovation, with different cultural dimensions that affect innovation differently. These influences vary across historical stages, highlighting their continuous and diverse nature.

Therefore, in recent years, the importance of culture in fostering innovation and driving economic growth has gained prominence in scholarly discourse. Scholars such as Fagerberg and Srholec (2018) have emphasised the role of innovation systems and governance, and cultural aspects that underpin these systems. They postulated that culture plays a crucial role in shaping the innovation landscape of nations. In fact, cultural dimensions, as identified by scholars like Hofstede (1994), interact with institutional factors to influence a country’s innovation capabilities. This highlights the importance of understanding and leveraging cultural dynamics in innovation ecosystems. Accordingly, policymakers and business leaders are increasingly recognising the need to foster cultures that encourage creativity, collaboration, and risk-taking. By embracing cultural diversity and promoting inclusive practices, organisations can unlock the full potential of their workforce and drive innovation forward. Thus, culture emerges as a central theme in discussions surrounding innovation, shaping the strategies of individual firms and the broader economic landscape. Using the aforementioned literature as a starting point, the primary inquiry of the authors’ study revolves around the relationship between culture and innovation at the national level of economies.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: PDI, IDV, MAS, UAI, LTO, and IND—offer a theoretical framework to understand behavioural differences across countries. These dimensions are relatively stable over time and thus suitable for examining structural factors influencing innovation (Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2011). Several of these dimensions are theorised to encourage innovation by fostering openness to risk, individual creativity, long-term planning, and tolerance for ambiguity critical in the innovation process (Goncalo & Staw, 2006; Shane, 1993).

Empirical evidence on culture and innovationNumerous empirical studies validate the theoretical association between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and innovation. In particular, IDV has been consistently observed to correlate positively with innovation performance (Bonetto et al., 2022; Goncalo & Staw, 2006). In individualistic societies, individuals are encouraged to act autonomously, question authority, and take initiative-traits that align with entrepreneurship and knowledge creation. IND, reflects the extent to which a society allows gratification and enjoyment, while playing a facilitating role. High indulgence societies are more open to novelty, personal freedom, and risk-taking, which are essential conditions for innovation and experimentation (Escandon-Barbosa et al., 2022; Kutan et al., 2021). LTO has been associated with innovation through a focus on future-oriented investment, persistence, and adaptive change. It supports strategic patience and planning—two critical attributes in building innovation infrastructure (Celikkol et al., 2019). Conversely, PDI and UAI are typically considered impediments to innovation. High PDI discourages open communication and participatory decision-making, while high UAI limits experimentation owing to an aversion to ambiguity and failure (Parveen et al., 2023; Veiga, Floyd, & Dechant, 2001). MAS yields more ambiguous results; while competitiveness and assertiveness may enhance innovation in specific domains, high MAS often undermines collaboration and social openness, which are crucial for long-term innovation success (Prim et al., 2017). Table 1 synthesises common findings from the literature:

Summary of Hofstede Dimensions and their empirical relationship to innovation.

| Hofstede Dimension | Effect onInnovation | Key Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Individualism (IDV) | Positive | (Bonetto et al., 2022); (Goncalo & Staw, 2006); (Bate et al., 2025) |

| Indulgence (IND) | Positive | (Escandon-Barbosa et al., 2022); (Kutan et al., 2021); (Bate et al., 2025) |

| Long-Term Orientation(LTO) | Positive | (Celikkol et al., 2019); (Muskat et al., 2021); (Bate et al., 2025) |

| Power Distance (PDI) | Negative | (Veiga et al., 2001); (Prim et al., 2017); (Silva et al., 2022) |

| Uncertainty Avoidance(UAI) | Negative | (Tian et al., 2018); (Clouet et al., 2024) |

| Masculinity (MAS) | Mixed | (Prim et al., 2017); (Kutan et al., 2021) |

These findings underscore the importance of aligning innovation policies with cultural context, recognising that certain traits may either enable or inhibit creative capacity. However, culture should be viewed as one component of a broader systemic framework rather than a deterministic factor.

Bundled cultural profiles and innovationRecent research emphasises that individual dimensions should not be evaluated in isolation. The concept of cultural bundling (Bate, 2022; Tekic & Tekic, 2021) posits that innovation is accurately predicted by combinations of cultural traits that coalesce to form coherent cultural profiles. High-innovation bundles typically consist of low PDI, high IDV, low UAI, high IND, and strong LTO.

For example, countries like the Netherlands and Sweden, which combine high IDV and IND with low PDI and low UAI, tend to achieve top rankings in innovation indices. On the contrary, countries with high PDI, UAI, and MAS characteristics more typical of hierarchical or rigid cultures often struggle to adapt to innovation-driven economic change.

This bundling perspective can help explain why some countries with moderately high IDV may still lag in innovation—due to the counterbalancing effects of other cultural traits. It also underlines the importance of policy alignment with cultural realities.

EU Focus and the SIIDespite the abundance of global analyses, relatively few studies focus on the EU, where shared regulatory frameworks coexist with deep-rooted cultural heterogeneity. SII, compiled annually as part of the EIS, provides a composite measure of national innovation capacity, combining inputs (e.g. R&D investment, digital skills) and outputs (e.g. patent applications, innovation in SMEs).

Andrijauskienė, M., & Dumčiuvien (2017), as well as Khan and Cox (2017), are among the few researchers who have attempted to link Hofstede’s cultural dimensions directly to SII-type measures (Boubakri et al., 2021). These studies confirm a positive association between IDV and IND and national innovation levels, and a negative relationship between PDI and UAI. However, these studies often suffer from two primary limitations: their reliance on cross-sectional instead of longitudinal data, and the lack of distinction between static innovation levels and improvements over time.

Addressing research gapsThe review of the literature reveals three primary gaps that the present study aims to address:

- 1.

Underrepresentation of EU-specific analysis: Most prior studies use global data without fully accounting for the institutional homogeneity and cultural diversity within the EU.

- 2.

Lack of longitudinal perspective: Few studies assess whether cultural values can explain upward movement in innovation performance over time. This is particularly relevant in the context of the EIS’s evolving classification of member states.

- 3.

Insufficient integration of theory and method: More structured empirical testing that aligns theoretical propositions with quantitative evidence—including both regression analysis and group comparisons—is needed.

By building on extant literature, the present study integrates updated (2024) SII data with Hofstede’s cultural indicators to evaluate both current innovation performance and temporal improvement, offering a nuanced contribution to the discourse on cultural determinants of innovation in the EU.

MethodologyTwo-stage empirical design for assessing cultural impacts on innovationThe empirical strategy of this study is structured in two complementary stages that together aim to assess how cultural factors shape national innovation performance in the EU. The design combines theoretical validation, statistical testing, and comparative analysis to provide both depth and breadth in addressing the research questions.

In the first stage, a targeted literature review identified key cultural dimensions—IDV and IND—that are repeatedly associated with innovation outcomes in prior studies. These dimensions are then subjected to empirical testing through regression analysis using the latest SII scores from the 2024 EIS. This phase establishes whether cultural indicators are statistically associated with current levels of innovation across EU countries. The second stage shifts the focus from cross-sectional association to dynamic performance. Here, countries are grouped based on whether they improved their innovation category between 2017 and 2024. Comparative analysis is conducted to evaluate whether cultural factors such as IDV and IND can also explain this upward movement, indicating whether such traits are correlated with innovation level and can contribute to improvement over time.

This two-stage approach provides a robust methodological structure to investigate both cross-sectional and temporal dimensions of innovation performance in the EU. By combining regression analysis, group testing, and predictive modelling, this study offers a multi-layered understanding of the role of culture in shaping national innovation outcomes.

Data sources and variable descriptionThe innovation performance data are sourced from the 2024 edition of the EIS, published by the European Commission. The key dependent variable is the SII, a composite index that measures national innovation performance based on 32 indicators classified into four main dimensions: framework conditions, investments, innovation activities, and impacts.

In the EIS 2024, Member States are categorised into four innovation groups based on their relative scores: Innovation Leaders (performance above 125% of the EU average), Strong Innovators (between 100% and 125%), Moderate Innovators (between 70% and 100%), and Emerging Innovators (below 70%). As illustrated in Fig. 1, classification provides a meaningful basis for both continuous and categorical assessment of innovation capacity across the EU countries.

The cultural data were derived from the Hofstede Insights country comparison tool, which operationalises national culture through six standardised dimensions: PDI, IDV, MAS or motivation towards achievement and success, UAI, LTO, and IND. These indicators are expressed as continuous scores on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating a stronger presence of the respective trait. Hofstede’s model is widely used in comparative international studies due to its wide applicability, consistency, and empirical grounding. Notably, cultural scores are considered temporally stable, making them suitable for comparative analysis over time.

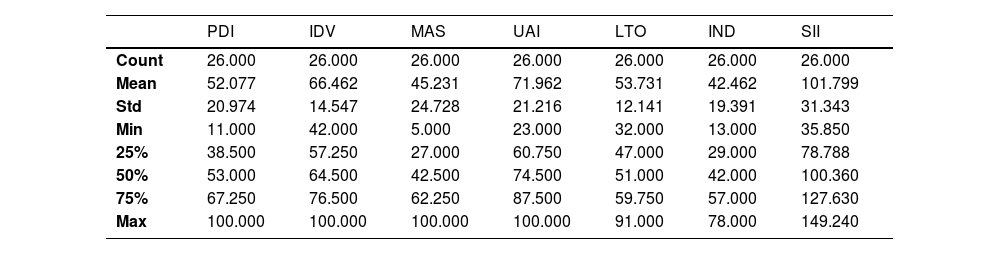

The final dataset includes 26 EU member states. One country (Cyprus) was excluded. Missing Hofstede’s values were an issue, and imputation procedures were necessary. The combined dataset includes each country’s SII value in 2024 and corresponding Hofstede scores. The descriptive statistics of the variables of the final dataset are presented in Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables in the final dataset.

The dataset consists of 26 EU countries and includes seven variables: six cultural dimensions (PDI, IDV, MAS, UAI, LTO, IND) and the SII. All six cultural dimensions range from a minimum of 5 and 42 to a maximum of 78 to 100, indicating full-scale representation across the EU sample.

Notably, while IDV exhibits a moderately concentrated distribution around the mean, indicating convergence in individualist values, IND appears more polarised. This divergence may possess important implications for how national cultures foster structural and behavioural enablers of innovation. This statistical overview underscores both the cultural heterogeneity of the EU and the uneven distribution of innovation performance. These insights form the foundation for the subsequent regression and comparative analysis exploring whether these cultural traits can explain innovation disparities or trajectories over time.

Stage 1: regression analysisStage 1 investigates the statistical relationship between national culture and innovation performance in EU countries. A multiple linear regression analysis is conducted, treating the 2024 SII as the dependent variable and Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions as independent variables.

Model constructionA regression analysis is conducted instead of simple correlation to allow for stronger inference of the effect of cultural traits on innovation performance. The regression model is implemented using the statsmodels.OLS module in Python. Before estimation, a constant term is added using add constant, and all independent variables are standardised to ensure comparability and mitigate scale-related biases.

The full model includes all six Hofstede cultural indicators as predictors: PDI, IDV, MAS, UAI, LTO, and IND. The regression equation is specified as follows:

Assumption testing and diagnosticsMulticollinearity is verified using variance inflation factors (VIF). VIF scores above 10 are considered problematic; although some interdependence appears among the predictors, it does not exceed critical thresholds.

Normality of residuals is examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and residual plots are generated. Minor deviations from normality are observed, but they are not substantial enough to violate the assumptions of ordinary least squares regression. Homoscedasticity is assessed through visual inspection of residuals plotted against fitted values, revealing no strong evidence of heteroscedasticity. The regression output provides coefficients, standard errors, t-values, and significance levels for each predictor. Model fit is evaluated using the R2 statistic and adjusted R2. The results are presented in detail in the Results section.

Based on the significance levels and direction of the regression coefficients, the analysis identifies which cultural dimensions exhibit a positive and statistically significant relationship with innovation performance. A reduced regression model is then constructed using only the variables observed to be statistically significant. This model serves as the basis for the second stage of the study, which examines whether the identified cultural traits also explain improvement in innovation performance over time.

Stage 2: group-based comparisonStage 2 examines whether cultural traits are associated with absolute innovation levels and improvement over time.

Group creationCountries are categorised based on their change in innovation performance group between the 2017 and 2024 editions of the EIS. Using the EIS classification labels (e.g. ‘moderate innovator’, ‘strong innovator’), countries that move to a higher group are labelled ‘upward movers’, while those that remain in the same category or decline are labelled as ‘non-upward’. A binary grouping variable (advanced) is created for this purpose, where a value of 1 indicates upward movement and 0 indicates no change or decline.

T-test procedureIndependent-sample t-tests are performed using scipy.stats.ttest to compare the mean values of the selected cultural dimensions between the two groups. The tests are two-tailed and assume equal variances. Normality and variance homogeneity are assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. This approach enables the evaluation of whether group-level cultural differences are statistically significant.

All coding, model fitting, and diagnostics were performed using Python (Google Colab), employing the statsmodels, scipy, sklearn, matplotlib, and seaborn packages. The entire workflow ensures reproducibility and transparency in data processing.

Overview of variablesTable 3 provides an overview of the key variables used in this study, including their type, source, and a brief description. The dependent variable is the 2024 SII, while the chief independent variables are Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions. A binary grouping variable is also introduced to capture whether a country has improved its innovation performance classification between 2017 and 2024.

Overview of variables.

| Variable | Type | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| SII (2024) | Dependent | EIS (2024) | Summary Innovation Indexmeasuring national innovation performance |

| IDV | Independent | Hofstede | Individualism score: the degree of interdependence in society |

| IND | Independent | Hofstede | Indulgence score: the extent to which gratification and leisure are permitted |

| PDI | Independent | Hofstede | Power Distance Index: the acceptance of unequal power distribution |

| MAS | Independent | Hofstede | Masculinity score: orientation towards competition and achievement |

| UAI | Independent | Hofstede | Uncertainty Avoidance Index: tolerance for ambiguity and risk |

| LTO | Independent | Hofstede | Long-Term Orientation: focus on future rewards and perseverance |

| Upwardgroup dummy | Grouping | EIS(2017-2024) | Binary variable:1 - if the country moved to a higher innovation group0 - if not moved to a higher innovation group |

The analytical framework assumes that national culture influences both the level and the development of innovation performance over time. To explore this relationship, the methodology follows a two-phase logic:

- 1.

Regression analysis for assessing the association between cultural dimensions and innovation performance; and

- 2.

Comparative testing for examining whether specific cultural traits explain upward movement in innovation group classification over time.

This stepwise design—grounded in theory, validated empirically, and assessed comparatively—provides a robust structure for investigating both cross-sectional and temporal dimensions of innovation in the EU. By combining regression analysis and group testing, this study offers multi-layered understanding of the role of culture in shaping national innovation outcomes.

Each analytical step is directly linked to the stated research questions and hypothesis: Stage 1 regression evaluates the statistical relationship between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and the SII, providing evidence for RQ1 and testing H1 and H2. In Stage 2, countries are categorised based on their change in innovation group status between 2017 and 2024, and independent-sample t-tests are conducted to compare cultural characteristics across these groups. This second phase addresses RQ2 and tests H3 and H4. To summarise, the methodological framework aligns theoretical assumptions with empirical procedures to ensure validity and clarity of the conclusions of the study.

ResultsDescriptive statistics overviewThe descriptive statistics reveal substantial variation across EU countries in terms of both cultural dimensions and innovation performance. The mean score for the SII across the 26 countries is 101.80, with values ranging from a minimum of 35.85 to a maximum of 149.24. This wide range reflects the persistent disparity in innovation capabilities across Europe. Countries with SII above the 75th percentile (127.63) represent the strongest innovators, while those below the 25th percentile (78.79) fall within the modest innovator group.

Among the Hofstede dimensions, PDI varies considerably, with a minimum of 11 and a maximum of 100, indicating large differences in hierarchical acceptance across societies. IDV exhibits a high average (mean = 66.46) with relatively moderate dispersion (SD = 14.55). Most countries range between 57.25 and 76.50 (interquartile range), indicating cultural leaning towards individual autonomy and self-reliance. IND displays a lower mean value (42.46) but greater variability (SD = 19.39), highlighting diverse societal attitudes towards gratification, leisure, and emotional expression.

MAS, which reflects a society’s orientation towards competition and achievement, exhibits a wide range (min = 5, max = 100), with an average of 45.23 and the highest standard deviation among all variables (24.73). This indicates substantial cultural differences in value systems related to gender roles and assertiveness. UAI, with a mean of 71.96 and values ranging from 23 to 100, indicates that most EU countries exhibit a relatively high preference for rules, structure, and predictability, though some exhibit much lower levels. LTO demonstrates more moderate variation (mean = 53.73, SD = 12.14), reflecting differing emphases on future planning and persistence. These cultural variations serve as the foundation for the subsequent analysis of their impact on innovation performance.

A boxplot analysis (Fig. 2) visualises the distribution of all variables. IND and MAS exhibit the highest range, indicating considerable cultural variation in IND and MAS across EU countries. SII also displays a wide range, further justifying the choice of regression and group comparison analyses to explore underlying patterns.

Results of the full regression model (stage 1)As shown in Table 4, the multiple linear regression model reveals that among Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, only IND is positively and significantly associated with innovation performance (p = 0.031). IDV, although positively related to SII, does not reach significance in the full model (p = 0.187). PDI, MAS, UAI, and LTO all yield non-significant coefficients.

The model illustrates substantial variance in SII, with an R2 of 0.692 and an adjusted R2 of 0.595. However, multicollinearity—listed on Table 5—is observed: in particular, for IDV (VIF = 40.9) and LTO (VIF = 28.3)—which may obscure the individual effects of these variables.

Assumption diagnostics confirm no severe violations of normality or homoscedasticity. These findings offer only partial support for H1, which proposed a positive association between IDV and innovation performance. While the regression coefficient for IDV is positive, indicating that more individualistic societies tend to perform better in innovation, the relationship does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in the full model (p = 0.187). This indicates that although IDV may contribute to innovation capacity, its effect is less robust when considered along with other cultural variables.

In contrast, the results clearly support H2, which posited that IND is positively associated with innovation performance. The regression analysis reveals that IND is a statistically significant predictor (p = 0.031), even in the presence of other cultural dimensions. This indicates that societies characterised by greater permissiveness, openness to gratification, and support for leisure and personal freedom tend to foster more favourable innovation environments. In such cultures, individuals may feel more empowered to take creative risks, pursue unconventional ideas, and challenge established norms—all of which are essential drivers of innovative activity. Thus, indulgence appears to play a more distinct and enabling role in shaping national-level innovation outcomes compared to IDV.

Results of the reduced modelTo improve interpretability and reduce multicollinearity, a reduced regression model was estimated using IDV, IND, and LTO as predictors. All three variables exhibited positive coefficients in relation to innovation performance, indicating that higher levels of these cultural traits are associated with stronger innovation outcomes. Among them, IND was statistically significant at the 5% level (p = 0.031), while IDV and LTO were not statistically significant (p = 0.187 and p = 0.177, respectively), though their positive direction is consistent with theoretical expectations. Although the literature indicates that LTO may play a role in shaping innovation outcomes, its empirical contribution in this model was limited. In the reduced model, VIF analysis revealed moderate levels of multicollinearity, with IDV and LTO demonstrating VIF values of 2.54 and 1.43, respectively. Thus, this reduced model was tested to assess whether LTO adds explanatory power beyond IDV and IND. While the model demonstrated a solid overall fit (R2 = 0.654, adjusted R2 = 0.607), LTO was not statistically significant (p = 0.178) in this model, whereas IND remained significant (p = 0.009) and IDV demonstrated marginal significance (p = 0.096).

To maintain a parsimonious and interpretable model, LTO was excluded from the final specification. The final reduced model retained only IDV and IND, the two most theoretically and empirically robust predictors. In this specification, both IDV (p = 0.010) and IND (p = 0.015) were statistically significant and positively associated with innovation performance (SII). The adjusted R2 remained strong (0.591), indicating that these two cultural dimensions combined explain the cross-country variance in innovation capacity to a substantial degree.

Scatterplots with linear trendlines (Figs. 3 and 4) visually confirm these associations. This supports both H1 and H2 within the reduced model, highlighting the importance of these dimensions when not confounded by other overlapping cultural traits.

Group comparison: upward vs. non-upward countries (stage 2)To assess whether cultural traits influence changes in innovation classification over time, countries were grouped based on whether they improved their EIS ranking between 2017 and 2024. Independent-sample t-tests compare IDV and IND scores across the two groups.

For IDV, the mean score is higher among upward movers, but the difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.585). Similarly, IND differences between groups are also non-significant (p = 0.368). These findings suggest that while IDV and IND are positively associated with current innovation levels, they do not explain upward mobility over time. Thus, H3 and H4 are not supported.

Cross-validation with literatureThe results partially support earlier theoretical and empirical studies. The enabling role of indulgence is supported, consistent with the findings of Escandon-Barbosa et al. (2022), as well as Jourdan and Smith (2021). The mixed findings for IND reflect multicollinearity issues reported in other studies (e.g. (Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2011)). The lack of association for upward movement contrasts with the indication that stable cultural values may not fully explain temporal change within culturally similar EU contexts.

Summary of hypothesis testingTable 6 summarises the results of the hypothesis testing conducted in this study. H1 and H2 addressed RQ1 on the relationship between cultural values (IDV and IND) and current innovation performance. H3 and H4 corresponded to RQ2, examining whether these traits explain improvement in innovation group classification between 2017 and 2024.

Summary of hypotheses testing.

The results of the statistical analyses reveal that cultural dimensions have a selective influence on national-level innovation performance in the EU. IND emerged as the most robust predictor: it exhibited a statistically significant positive relationship with innovation performance in both the full and reduced regression models.

This provides strong empirical support for the notion that societies with higher tolerance for gratification, freedom, and leisure tend to foster innovation more effectively. Contrastingly, IDV was not statistically significant in the full model but gained significance in a reduced model that excluded collinear variables. This implies that IND does share a positive relationship with innovation performance, but its explanatory power is partially masked when other overlapping cultural traits are included. Therefore, H1 is only partially supported, while Hypothesis 2 is clearly confirmed.

When assessing whether cultural traits are associated with upward movement in innovation performance between 2017 and 2024, the findings are less conclusive. Neither IDV nor IND exhibited statistically significant differences between countries that improved their innovation group classification and those that did not. The t-tests for both variables yielded p-values well above conventional thresholds for significance, indicating that these cultural traits are not reliable predictors of temporal improvement in innovation classification. Consequently, hypotheses 3 and 4 are not supported.

To summarise, the analysis indicates that while certain cultural characteristics—most notably –IND—can explain differences in current innovation performance among EU member states, they do not appear to drive dynamic progress over time. These findings underscore the importance of distinguishing between static innovation capacity and ongoing innovation development, indicating that institutional, political, and structural factors may play a more decisive role in long-term innovation advancement.

Discussion, implications, and conclusionsDiscussionThis study examined the relationship between national cultural values—particularly IND and IDV—and innovation performance across EU member states. The findings reinforce long-standing theoretical claims of cultural values influencing innovation outcomes. In particular, IND emerged a robust and statistically significant predictor of innovation performance, aligning with research that emphasises the role of freedom, gratification, and autonomy in fostering creative behaviour and risk-taking. IDV, although not significant in the full regression model, demonstrated significance in a reduced specification, indicating a conditional relationship potentially masked by multicollinearity.

These results confirm the relevance of cultural traits as structural enablers of national innovation systems, echoing prior studies (e.g. Bonetto et al., 2022; Escandon-Barbosa et al., 2022). However, they also caution against deterministic interpretations: culture does not operate in isolation. Instead, innovation appears to emerge from configurations of complementary traits and systemic interactions between cultural, institutional, and economic conditions.

Contrastingly, the second stage of analysis challenges the idea that cultural values directly enhance innovation performance over time. Countries that moved to higher performance groups in the EIS between 2017 and 2024 did not display significantly higher IND or IDV values. This aligns with recent findings by Bresciani et al. (2021), who demonstrated through multilevel analysis that innovation efficiency across Spanish and Italian regions is significantly influenced by the stringency of environmental policies and sustainability measures—underscoring that innovation outcomes are shaped by cultural context and broader environmental and institutional conditions. Therefore, culture should be treated as a background condition—notable but not sufficient by itself.

Theoretical and methodological implicationsThe findings of this study contribute to a growing shift in innovation research from linear, trait-based interpretations of culture towards more holistic, configurational perspectives. The observed multicollinearity among Hofstede’s dimensions indicates that national culture is best conceptualised as a bundle of interrelated values rather than discrete, independent traits. Recent contributions (e.g. Bogers et al., 2018; Gonzalez-Loureiro et al., 2018) highlight that innovation outcomes are often the result of synergistic cultural profiles. Countries such as Sweden and the Netherlands exemplify coherent configurations—high in IND and IDV, low in PDI and UAI—that collectively foster openness, autonomy, and risk tolerance.

To better capture such configurations, advanced methodological approaches—including cluster analysis and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis—may offer greater explanatory power than traditional regression-based techniques. Future research can also integrate alternative cultural frameworks, such as the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) Project or the World Values Survey, to triangulate insights and address the limitations associated with Hofstede’s legacy data.

Notably, culture operates within broader systemic arrangements. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of national innovation performance must also account for institutional quality, governance capacity, technological infrastructure, and education systems. These elements interact dynamically with cultural predispositions, shaping innovation systems through complex, context-specific pathways.

From a methodological standpoint, limitations persist. Hofstede’s scores, while widely used, are based on data collected decades ago and may no longer reflect contemporary cultural dynamics, especially amid accelerating societal change. In addition, the dichotomous categorisation of countries into ‘upward’ and ‘non-upward’ innovation trajectories—though analytically useful—risks oversimplification of inherently non-linear and path-dependent processes. To address these concerns, future research should adopt panel data techniques, incorporate subnational and/or regional-level analyses, and employ mixed-method designs to enrich both temporal and contextual precision.

This study also contributes to narrowing persistent gaps in the literature. Particularly, it responds to the underrepresentation of EU-focused research in cultural innovation studies. Much of the existing literature relies on global datasets that overlook the unique institutional homogeneity and cultural diversity within the EU. By focusing exclusively on EU member states, this study offers context-sensitive insights that are directly aligned with European innovation policy frameworks and academic discourse.

Finally, this study helps bridge the often-cited gap between conceptual models and empirical testing. Cultural frameworks like Hofstede’s are frequently referenced without rigorous hypothesis validation. By applying a two-stage design—combining regression analysis and group comparison—this research strengthens the empirical foundations of cultural innovation theory and provides a replicable approach for future studies.

Practical implications and policy relevanceBeyond its theoretical contributions, this study offers practical insights for innovation policy at both EU and national levels. While national culture functions as a relevant contextual enabler of innovation capacity, its influence should be interpreted with caution. The empirical findings indicate that permissive and individualistic societies may enjoy a higher baseline of creative autonomy and institutional trust factors that are favourable for innovation. However, such cultural attributes alone do not ensure sustained progress in innovation performance.

This nuance holds important implications for the design and implementation of innovation policies. Specifically:

- •

EU innovation funding schemes (e.g. Horizon Europe) can benefit from a more culture-sensitive regional calibration, adjusting support instruments to the cultural profiles of different member states.

- •

National governments may consider fostering cultural attributes associated with innovation (e.g. tolerance of failure, openness to change) through education reform, public discourse, or organisational culture programmes.

- •

Innovation agencies and policymakers should be aware that structural levers, such as institutional trust, policy coherence, and long-term investment in R&D infrastructure, outweigh cultural factors in determining sustained innovation performance.

To summarise, innovation strategies should be culturally informed, but not culturally determined. Policymakers must guard against cultural determinism, which risks obscuring the more decisive political, institutional, and economic levers of innovation.

Future research directionsBuilding on the findings and limitations of this study, several directions emerge for future research on culture and innovation. First, there is a clear need for longitudinal and multi-level research designs that explore how cultural dispositions interact with national and supranational innovation regimes over time. Moving beyond static correlations, such approaches can help identify the causal pathways through which culture facilitates—or inhibits—innovation performance.

Second, researchers should consider applying alternative cultural frameworks, such as the GLOBE Project model or World Values Survey, to validate and extend findings derived from Hofstede’s dimensions. These models offer contemporary and nuanced measures of cultural values, which may better reflect evolving societal norms.

Third, greater attention should be paid to within-country regional dynamics. Mixed-method designs—including case studies, ethnographic research, and process tracing—can offer granular insights into how national-level cultural norms translate into organisational behaviour and innovation practices on the ground level.

Finally, future studies should integrate institutional and structural indicators—such as regulatory quality, policy coherence, digital readiness, and innovation governance capacity—into cultural analyses. This will allow for the development of multi-dimensional, context-sensitive models capable of capturing the comprehensive complexity of innovation system evolution. Together, these directions would help advance a holistic and dynamic understanding of the role of culture in innovation within the EU and beyond.

ConclusionIs innovation in your blood? This study set out to examine whether national cultural values—particularly IND and IDV—are deeply embedded traits that can explain differences in innovation performance across EU member states. The findings confirm that such values are indeed associated with higher baseline innovation capacity: IND emerged as a robust, statistically significant predictor, and IDV demonstrated conditional relevance. However, when it comes to improvement over time—measured by upward movement in innovation performance groups—these cultural traits do not provide explanatory power.

In this sense, the answer to the question posed by the title is both yes and no. Yes, culture shapes the initial conditions for innovation: it reflects long-term predispositions that influence autonomy, gratification, and openness to change. No, culture alone does not determine national innovation trajectories. Advancement requires more than what is ‘in the blood’. It is shaped by institutional quality, governance, education systems, and strategic investments.

This study contributes to a more nuanced perception of the role of culture in innovation, challenging deterministic interpretations. It argues for culturally informed—rather than culturally-constrained—innovation policies. For the EU, this means acknowledging cultural differences while strengthening systemic capacities that enable all member states to progress, regardless of their cultural profile.

FundingThis research was supported by project no 2023-2.1.2-KDP-2023-00012, implemented with the generous support of the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary, financed by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund under the KDP-2023 funding scheme.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMárk Végh: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. István Szabó: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Alexandra Kovács: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis.

The author(s) has/have declared that there are no competing interests.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Attila Pál, corporate expert, for his insightful contributions and expertise, and to Tamás Mészáros, Global AME Engineering and Automation Senior Manager, for his professional guidance and valuable support throughout the research process. Their involvement greatly enriched the depth and practical relevance of this study.