This conceptual article introduces a new perspective on innovation systems by emphasizing their dynamic, co-evolutionary nature. In today’s rapidly changing world, innovation should be understood as a heterogeneous, multidimensional, continuously evolving phenomenon embedded within complex patterns of co-evolutionary development. Although innovation systems have long been recognized as learning systems, this article deepens that perspective by framing learning not only as an internal function of those complex structures but also as a functional mechanism for designing systems interventions that catalyze and guide systemic transitions. Based on a systematic literature review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (i.e., PRISMA) and a qualitative reflective analysis, the article examines innovation systems as complex adaptive structures and conceptualizes them as collaborative learning environments, wherein diverse forms of knowledge and learning enhance a continuous feedback loop between systems interventions and learning processes. A qualitative analysis of 85 academic articles revealed three thematic clusters that consolidate the three dimensions of co-evolution within innovation systems through the interplay of agents, institutions, and innovation habitats: (1) the co-evolutionary landscape, (2) co-evolutionary dynamics and capacities, and (3) knowledge and learning processes. Building on those insights, the article advances the conceptualization of innovation systems as collaborative learning environments and extends that conceptual perspective into an analytical framework and applied mechanism, in which the integration of knowledge becomes an essential link for mutual learning, consensus building, and the co-creation of systems interventions.

In the late 1980s and mid-1990s, the foundational paradigm of the innovation system as a learning system was developed and embedded within the framework of a national innovation system (Freeman, 1987; Lundvall, 1992; Nelson, 1993). Echoing earlier insights made by Joseph Schumpeter and Friedrich List, the paradigm emphasized—and still emphasizes—the interactive, systemic, and institutionally embedded character of innovation, with particular focus on the interplay among diverse actors (Freeman, 1995; Lundvall et al., 2002). Although the paradigm remains a cornerstone in studies on innovation, it is increasingly regarded as insufficient for understanding the complex, dynamic nature of contemporary innovation processes. More recently, scholars have considered innovation systems and their learning functions within broader transitional contexts, including environmental sustainability (Fernandes et al., 2022), sustainable development (Calvo-Gallardo et al., 2022; Li, Wu, et al., 2023), digital transformation (Duarte & Carvalho, 2024), and sociotechnological change (Hekkert et al., 2007).

Even though innovation systems are commonly associated with the generation and diffusion of knowledge to meet socioeconomic goals (Calvo-Gallardo et al., 2022), the dominant paradigm of the learning system has shown limitations in addressing systemic lock-ins and barriers to change, particularly in relation to complex societal challenges (e.g., Geels, 2014). As a learning system, the innovation system is also frequently conceptualized without taking its interdependence with other societal systems into account. For instance, it is acknowledged that a system’s performance in developing and diffusing innovative knowledge depends not only on causal relations between the innovation system and its environment (e.g., Boons & McMeekin, 2019) or on the existence of coherent subsystems but also on the availability of structural couplings between them (Binz & Truffer, 2017). As a dynamic, multidimensional structure, an innovation system co-evolves with economic, ecological, technological, and social systems. At a broader level, that perspective aligns with the concept of coupled human–nature–technology systems (Haberl et al., 2011; Weisz et al., 2001), as well as highlights the shifting institutional boundaries of innovation systems, particularly in relation to geographic contexts, contextual embeddedness, and domains of transformation.

Against that backdrop, this article contributes to a reconceptualization of the innovation system as a complex, evolving structure that, through its learning dynamics, reflects and responds to the interconnected, constantly shifting dimensions of societal systems. A second key contribution lies in advancing the understanding of the learning process within those dynamics. Although knowledge is widely acknowledged as a crucial element of complex systems (McElroy, 2000; Moallemi et al., 2023; Rammel et al., 2007), it has yet to be integrated into a cohesive conceptual framework in which learning becomes a functional mechanism for driving systems transitions through innovation.

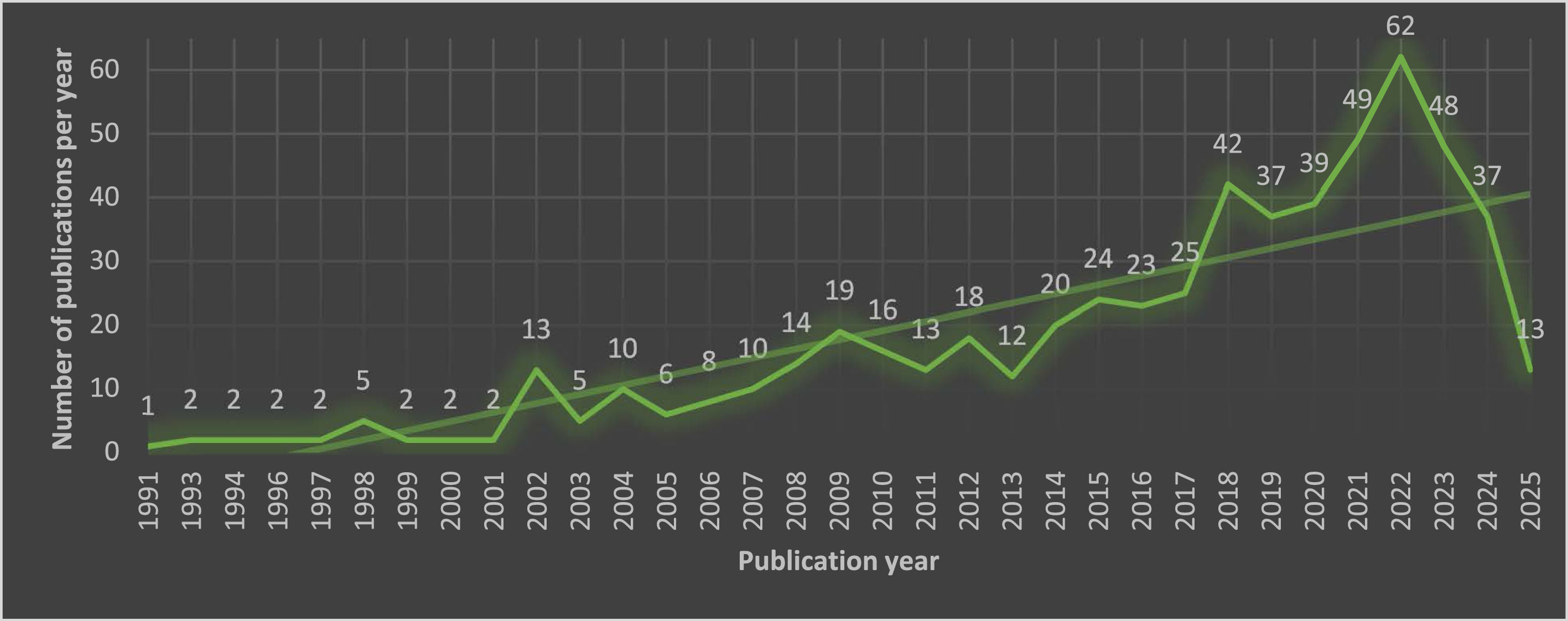

Complex systems, co-evolution, and knowledgeThe term co-evolution has been extensively applied to explain the performance and development of various complex adaptive systems—for instance, in investigating biological (e.g., Kauffman, 1993) and cultural changes (e.g., Durham, 1991), economic growth (e.g., Mokyr, 1992), industrial leadership (Murmann, 2003), and, most recently, polycrises (Steiner, 2025; Steiner et al., 2023). The literature shows, however, that the co-evolutionary lens has been rarely applied to analyze innovation systems and has yet to generate any concrete frameworks. Despite the proliferation of literature published on innovation systems in the past decade—more than 4,000 articles, according to Web of Science Core Collection—less than 2% explicitly focuses on co-evolution. That low rate is surprising given that evolutionary frameworks, including evolutionary economics, have been instrumental in studying innovation processes and systems for decades now (Cooke, 1996; Hanusch & Pyka, 2006; Moulaert & Sekia, 2003).

For the analysis of complex systems, adopting a co-evolutionary lens instead of a simple evolutionary one offers a more dynamic, interactive framework. Co-evolution means that two or more dimensions evolve simultaneously and, in the process, influence each other and create diverse configurations within and beyond their subsystems (Fritsch et al., 2019). Likewise, a co-evolutionary lens emphasizes mutual shaping of populations through reciprocal, adaptive relationships across domains and moving past the focus on mechanisms that achieve adaptation and selection only (Saviotti, 2005; Tsai et al., 2009). In co-evolutionary dynamics, knowledge plays a central role as both an outcome and a catalyst of interactions that shape formal (e.g., contractual) and informal (e.g., tacit) rules among key actors and institutions (Baggio, 2021; Breslin et al., 2021; Ruoslahti, 2020). Instead of serving merely as a passive carrier of information, knowledge is understood as a dynamic, socially embedded construct (Hayek, 2014) that facilitates mutual adaptation across interconnected systems and domains. Consequently, as a learning system, the innovation system should function as a dynamic guiding mechanism that facilitates the exchange, integration, and collective generation of knowledge (Li, Wu, et al., 2023) while nurturing collaborative engagement (Li, Chen, et al., 2023) and mobilizing resources and capabilities in support of transformative change.

Goal and objectivesIn response to the above, this article, by adopting a co-evolutionary perspective, seeks to enhance both the theoretical foundation and applied relevance of innovation systems and their learning capacity. Its three specific objectives are as follows:

Objective 1: Using a co-evolutionary lens, we aim to investigate innovation systems as complex adaptive structures whose core characteristics and recurring mechanisms are shaped by the dynamic interactions of diverse agents and institutions.

Objective 2: Building on that understanding, we aim to conceptualize innovation systems as collaborative learning environments that operate across the interconnected systems and domains and shape adaptive innovation pathways.

Objective 3: We also aim to offer an outlook on the integration and co-creation of knowledge as important mechanisms for generating innovative ideas that can be translated into systems interventions that enhance social impact and strengthen societal resilience.

To achieve those three objectives, we performed a comprehensive systematic literature review following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), complemented by a qualitative synthesis and reflective analysis.

The article is organized as follows. First, Section 2 introduces our research’s three guiding hypotheses based on the theoretical understanding of co-evolution as a specific mode of complex system dynamics that especially underscores the role of knowledge. Next, Section 3 outlines the methodology of systematic literature reviews, after which our findings are consolidated in Section 4. In Section 5, the discussion frames innovation systems as collaborative learning environments and highlights their potential as a functional mechanism for integrating knowledge and transforming systems. Section 6 then outlines the theoretical and practical implications of our results and offers an outlook for future research. In Section 7, the article concludes with a summary of our findings and their limitations.

Theoretical background and hypothesesOriginating in biology, the concept of co-evolution was first introduced by Paul Ehrlich and Peter Raven in their 1964 study on ecological interactions between interdependent species, including plants and herbivores (Ehrlich & Raven, 1964). Although evolution and co-evolution involve similar biological mechanisms, the term co-evolution specifically refers to mutual adaptations that result from ongoing interactions between two or more species or populations, as exemplified by predator–prey, host–parasite, and plant–pollinator relationships (Jeffrey & McIntosh, 2006; Jørgensen & Fath, 2008). Those mutual adaptations emerge from feedback mechanisms, in which changes in one species prompt reciprocal changes in another (Norgaard, 1984). Beyond biology, the term co-evolution has been used to describe the reciprocal interplay between genetic and cultural evolution, also called “gene–culture co-evolution” (Durham, 1991; Laland et al., 2000), and further adapted to explore reciprocal feedback processes in complex social and ecological systems (Rennings, 2000). As a result, co-evolution has become an analytical lens applied across various disciplines and areas of research for investigating the interactive dynamics of complex adaptive systems and their evolving institutional regimes. Along those lines, the first guiding hypothesis of our research suggests that a co-evolutionary paradigm provides a more holistic framework for understanding innovation systems in their complex adaptive structures. Those structures evolve through ongoing interactions among interconnected institutions, in which diverse agents engage in relational dynamics (Breslin et al., 2021; Dekkers, 2017).

Knowledge emerges as a core component of the ongoing process of co-evolution (Sotarauta, 2017) and can take multiple forms, whether professional, institutional, personal, and/or experiential. Crucially, knowledge and learning are predominantly “socially embedded” processes (Lundvall, 1992, p. 1) that are deeply rooted cultural predispositions shaped by a combination of professional practices and the presence of knowledge-intensive institutions. As such, co-evolutionary processes are closely intertwined with social dimensions such as behavior, culture, values, and trust (Gintis, 2003; Kaniadakis & Foster, 2024; Stagl, 2007). Within that landscape, networks of actors contribute to the development of dynamic knowledge-intensive subsystems that are institutionally embedded and that often transcend geographical boundaries (Binz & Truffer, 2017). The co-evolution of those subsystems gives rise to cross-institutional learning environments that foster new relationships and systemic properties (Fritsch et al., 2019). That dynamic inspired our second guiding hypothesis: that co-evolutionary interactions between diverse actors and institutional structures produce a collective system of knowledge (Samara et al., 2012) in which innovation pathways emerge through collaboration, mutual learning, and adaptive responses.

In complex adaptive systems, co-evolution encompasses not only adaptive change but also sensitivity to vulnerabilities, resilience, and pathways to sustainable development (Rammel et al., 2007). As in biological ecosystems, where species co-evolve through mutually influential relationships, institutional dynamics within innovation systems are often shaped by contradictory, complementary, and/or reinforcing interactions that collectively drive transformation (Zukauskaite et al., 2017). Those evolving institutional configurations are particularly relevant for understanding systems transitions across their multilevel, multidimensional trajectories (Ferloni, 2022; Rosenbloom, 2020). The evolving configurations driven by co-evolutionary processes, in transcending established sectoral and spatial boundaries, shape ongoing transformations (Coenen et al., 2012; Grin et al., 2010) as well as path dependencies (MacKinnon et al., 2019; Samara et al., 2012). Thus, our third guiding hypothesis suggests that innovation systems co-evolve much like biological species: through contradictory, mutualistic, and/or reinforcing institutional interactions. In turn, those interactions shape knowledge dynamics and influence the system’s adaptability, resilience, and trajectories toward long-term transformation.

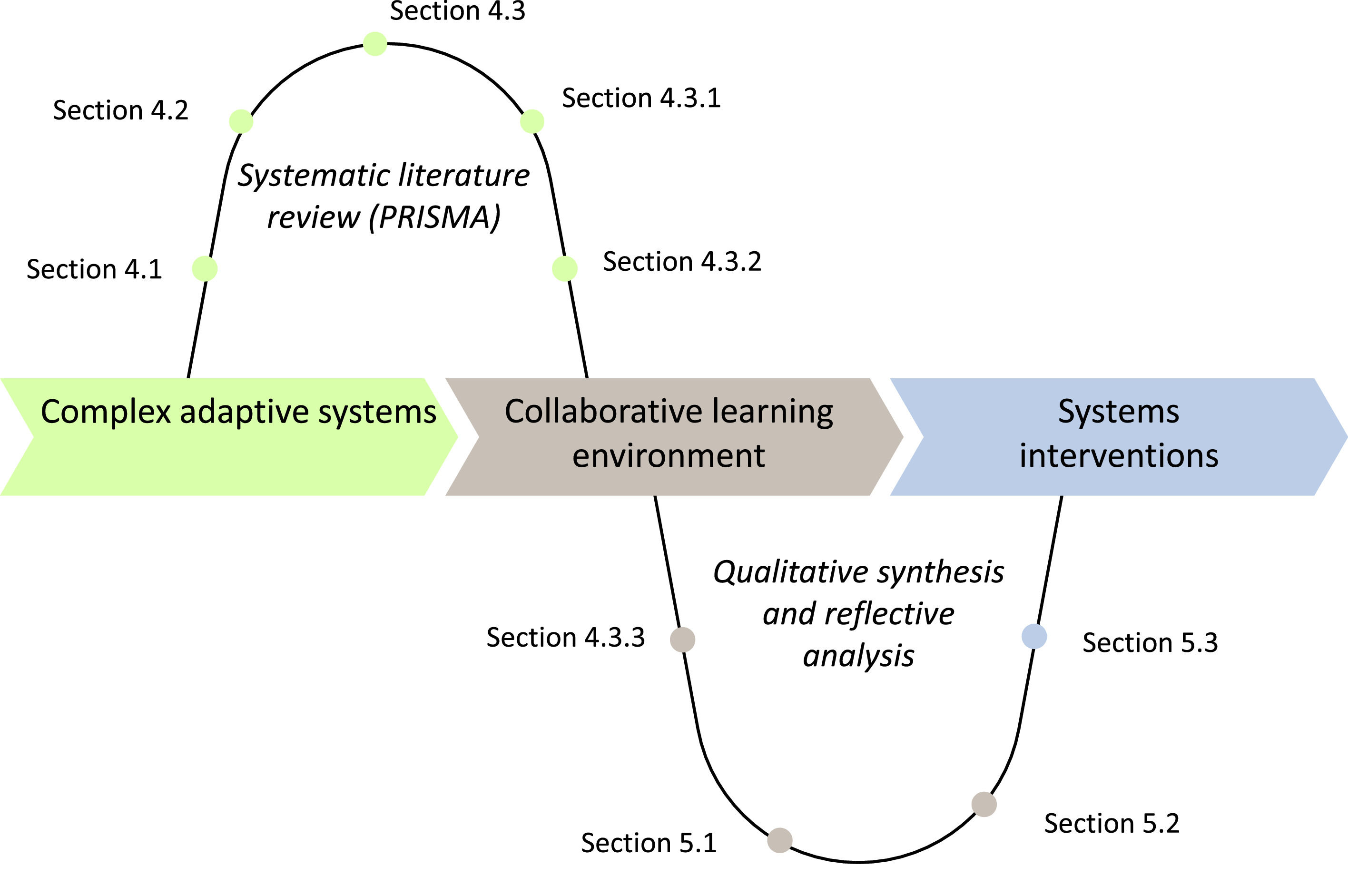

Our three guiding hypotheses, all interrelated and aligned with our research objectives (Fig. 1), each address a key dimension: the structural composition of an innovation system (i.e., Objective 1), the implementation of learning processes within it (i.e., Objective 2), and the broader societal impact that it generates (i.e., Objective 3).

MethodTo examine how existing approaches conceptualize innovation systems in the context of co-evolutionary dynamics, we conducted a systematic literature review. Building on insights gained from the review, we thereafter performed a qualitative synthesis and reflective analysis to further conceptualize innovation systems as collaborative learning environments. Reflections on those analyses also informed the development of an outlook on the integration and co-creation of knowledge as key mechanisms for translating innovative ideas into viable systems interventions. The research methods, aligned with our research’s objectives and the subsequent structure of the findings, are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Our systematic literature review was conducted according to PRISMA,1 which includes a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram. The PRISMA framework originated in 1999 as the QUOROM Statement (Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses), a guidance developed by an international team of experts to enhance reporting in meta-analyses, particularly in healthcare evaluations (Liberati et al., 2009). The PRISMA 2020 statement includes a checklist and flow diagram, complemented by the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration paper (Page et al., 2021). Designed for systematic reviews, PRISMA supports both synthesis-based approaches (e.g., meta-analyses) and non-synthesis-based approaches. Though initially aimed at improving transparency in clinical research, it is now widely used in systematic literature reviews across various fields. PRISMA’s key strength lies in providing a clear, structured reporting framework without detailing the review process itself.

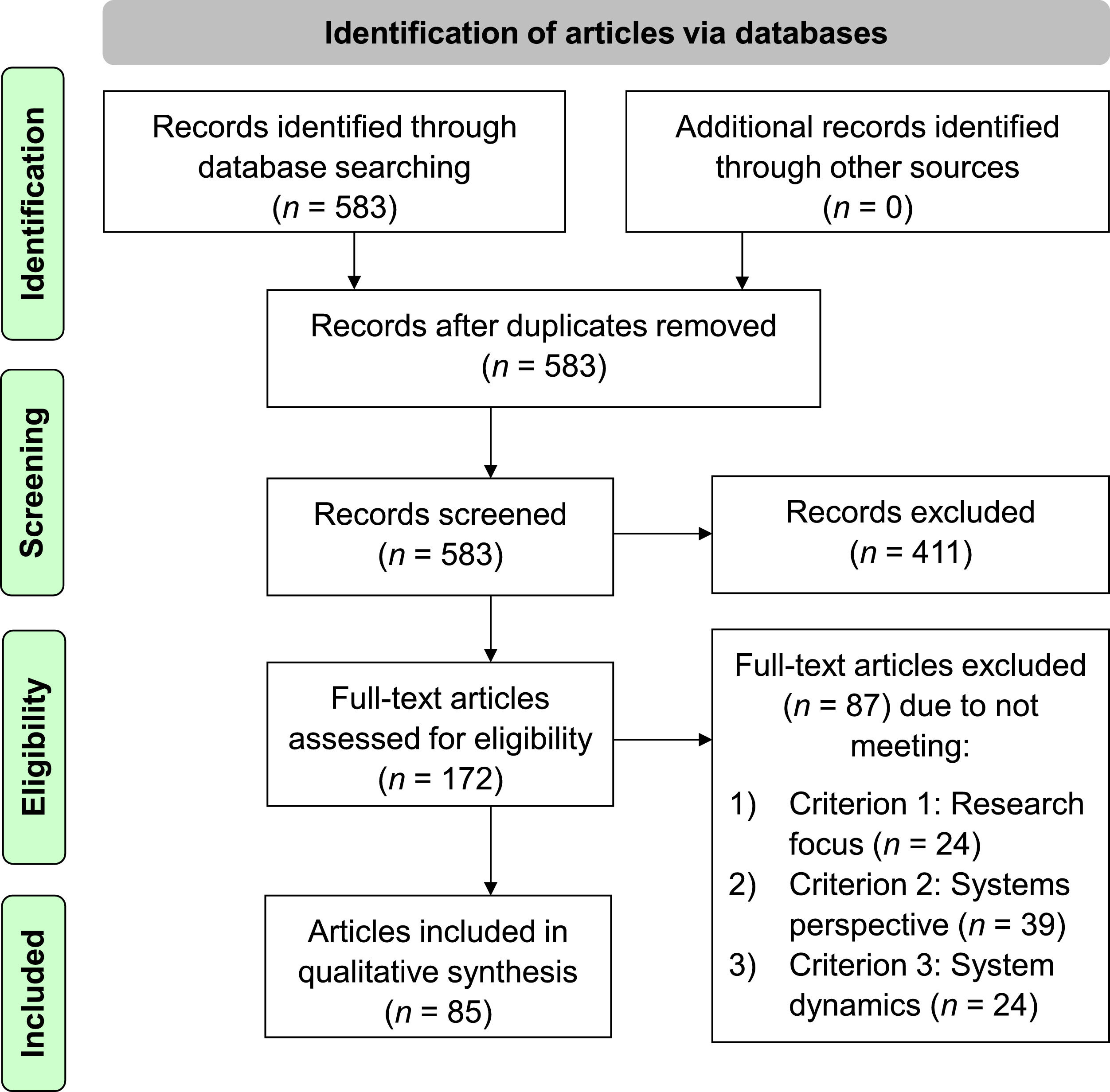

Following PRISMA, the process of selecting literature for our review unfolded in four steps: (1) identifying relevant records by searching through databases and excluding biases, (2) screening abstracts, (3) assessing the eligibility of the full-text articles, and (4) including them in a subsequent qualitative study. Fig. 3 schematizes the steps of the search process and the number of articles selected in each step.

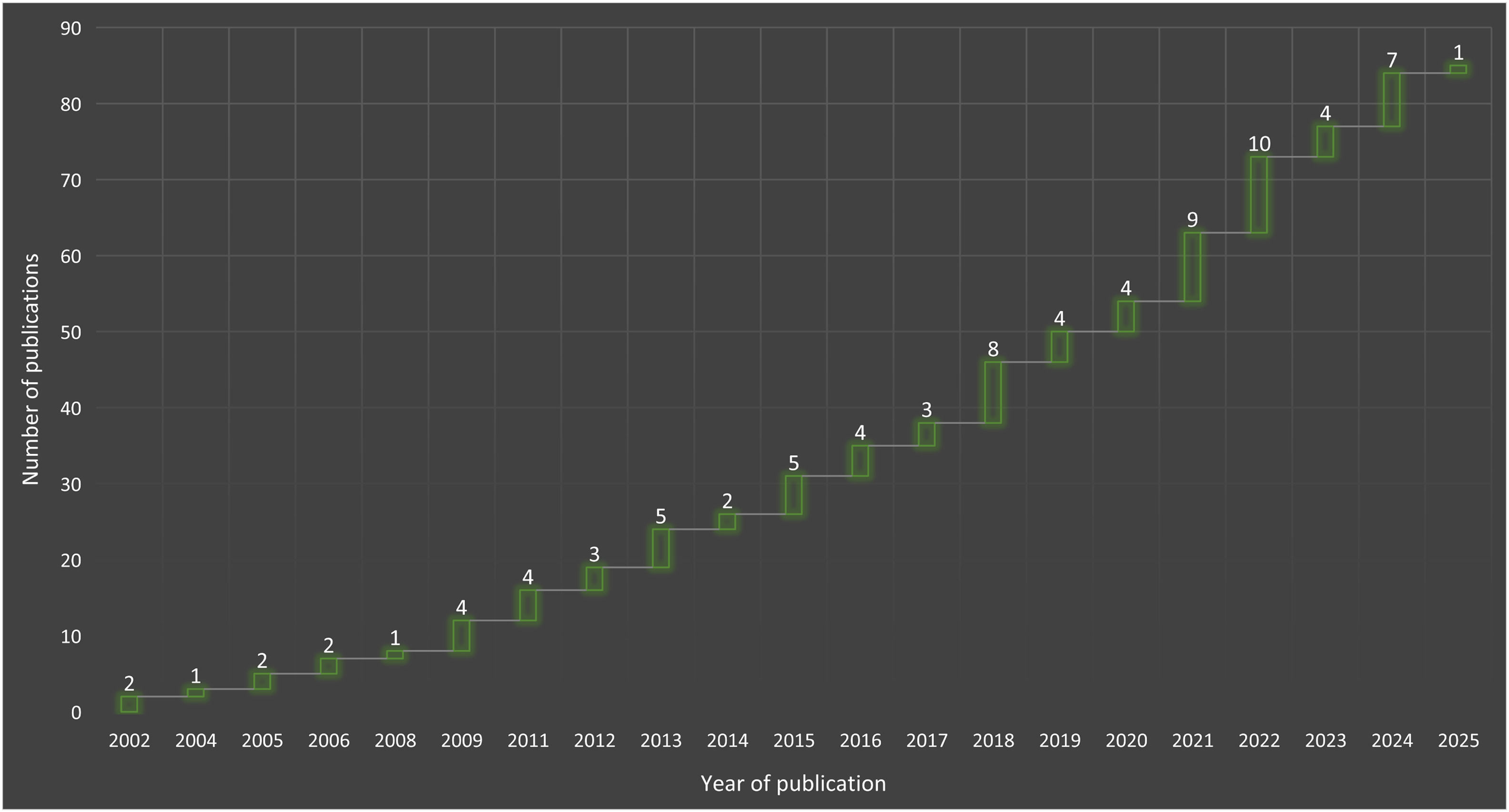

The literature search was performed using the Web of Science Core Collection managed by Clarivate Analytics. The search was performed using the “Topic” field with the algorithm TS=(“co-evolution” OR coevolution AND innovation*). The search term “innovation system” was intentionally excluded from the query due to its overly narrow scope, which yielded a limited number of relevant publications. In fact, all articles retrieved by the narrower query were also captured by the broader search algorithm and thus included in full-text screening. The broader formula also allowed identifying a more comprehensive pool of records while remaining aligned with the study’s objectives of focusing on innovation as a phenomenon embedded within a complex system of relationships, processes, actors, and influencing factors. The search algorithm was restricted to articles, review articles, and early-access articles without applying any limitations on the year of publication. The 583 records initially identified were published from 1991 to 2025, although with most entries concentrated in the past two decades (see Appendix A). For all identified records, a data sheet was created that contained key metadata, including the article’s title, the full name(s) of the author(s), the year of publication, the source’s title, the abstract, the keywords, and the DOI as a hyperlink. In the review, we focused on both conceptual and applied research exploring how co-evolutionary mechanisms or processes act as drivers, enabling forces, and/or outcomes of innovative activities that contribute to the formation, development, and/or transformation of innovation systems. Following the PRISMA protocol, the screening was first conducted based on abstracts and followed by an assessment of the full-text articles. Ultimately, 85 articles were selected for qualitative analysis.

Selection criteriaPrior to the screening process, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established based on three core dimensions: research focus, systems perspective, and system dynamics.

- (1)

Research focus: The article had to emphasize the process or mechanism of co-evolution and clearly link it to innovative activity as an integral component. Articles were excluded if

- •

Co-evolution was not explicitly part of the research objective, research questions, or conceptual framework;

- •

Co-evolutionary processes were not reflected in the study’s findings or results; and

- •

The relationship between co-evolution and innovation was not the chief focus of analysis—for instance, co-evolution was examined primarily in relation to a phenomenon (e.g., company growth) other than innovation.

- •

- (2)

Systems perspective: Because our objective was to understand co-evolution as a process that determines the formation, development, and/or transformation of innovation systems, articles were also excluded that

- •

Elaborate a very specific aspect or implication of innovation in the context of co-evolution without examining its interconnections within a broader innovation or societal system; and

- •

Do not consider innovative activity as a systems activity—that is, do not analyze it as part of a broader system—while articles referring to “innovation systems” were screened with special attention but included only if they also fulfilled Criteria 1 and 3.

- •

- (3)

System dynamics: We sought contributions exploring how co-evolution drives system dynamics, with innovation as an integral component of those changes. Articles were therefore excluded if the co-evolutionary process examined was merely associated with changes in specific elements without considering their reconfiguration with the broader environment of the system and without affording any insights into how the underlying systems were formed or have evolved and transformed.

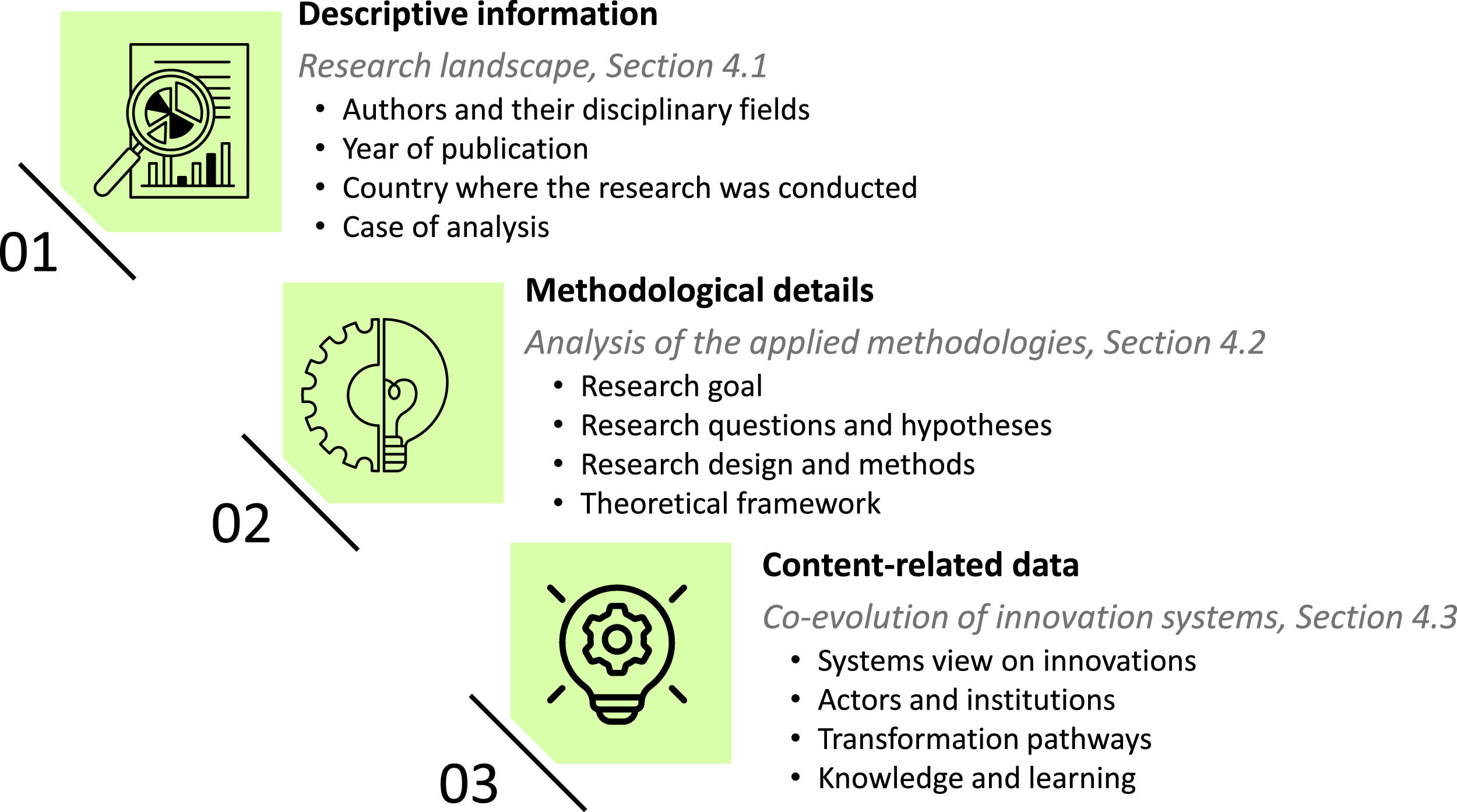

For the 85 articles selected for qualitative analysis, data collected during the screening process encompassed both descriptive and analytical information (Fig. 4).

The descriptive information focused on core bibliometric elements, along with the broader context of the documents that helped to define the publication scope, temporal trends, and geographic distribution of the research at the time of its publication, which contributed to an overall understanding of the field’s development. The analytical data focused on both the methodological design and the substantive content of the selected studies, which was particularly relevant information for addressing the research objectives and guiding the synthesis process. Methodological details helped to identify dominant patterns and gaps in the research. Building on the guiding hypotheses and theoretical background, we extracted content-related data to explore how innovation systems are conceptualized in relation to co-evolutionary processes. Due to the topic’s conceptual complexity, content-related data extraction did not rely on predefined variables or rigid coding schemes. Instead, a flexible, iterative approach was adopted to collect relevant insights in four key areas:

- •

Systems view on innovation: To begin, articles were examined for their conceptualization of innovation as a catalyst, driver, and/or outcome of systemic change and for how those roles relate to systemic configurations, structural boundaries, and different scales. Attention was given to the framing of innovation systems as dynamic, heterogeneous, multiscalar environments shaped by co-evolutionary interactions.

- •

Actors and institutions: In line with Hypothesis 1, data were gathered on how various actors, embedded within institutional frameworks, interact across different system boundaries. The analysis captured how those interactions are integrated within co-evolutionary dynamics and create environments that shape innovation-oriented trajectories.

- •

Transformation pathways: Aligned with Hypothesis 2, insights were extracted on how co-evolution drives broader systemic transformations. Articles were analyzed for discussions on shifting institutional regimes, the emergence of new systemic configurations, and changes in social practices. Themes of resilience, adaptability, and path dependency were also addressed.

- •

Knowledge and learning: In accordance with Hypothesis 3, the analysis focused on how knowledge is created, transferred, integrated, and diffused within innovation systems. Articles were thus reviewed for their conceptualizations of innovation as a collective, interactive process shaped by learning dynamics within co-evolutionary frameworks.

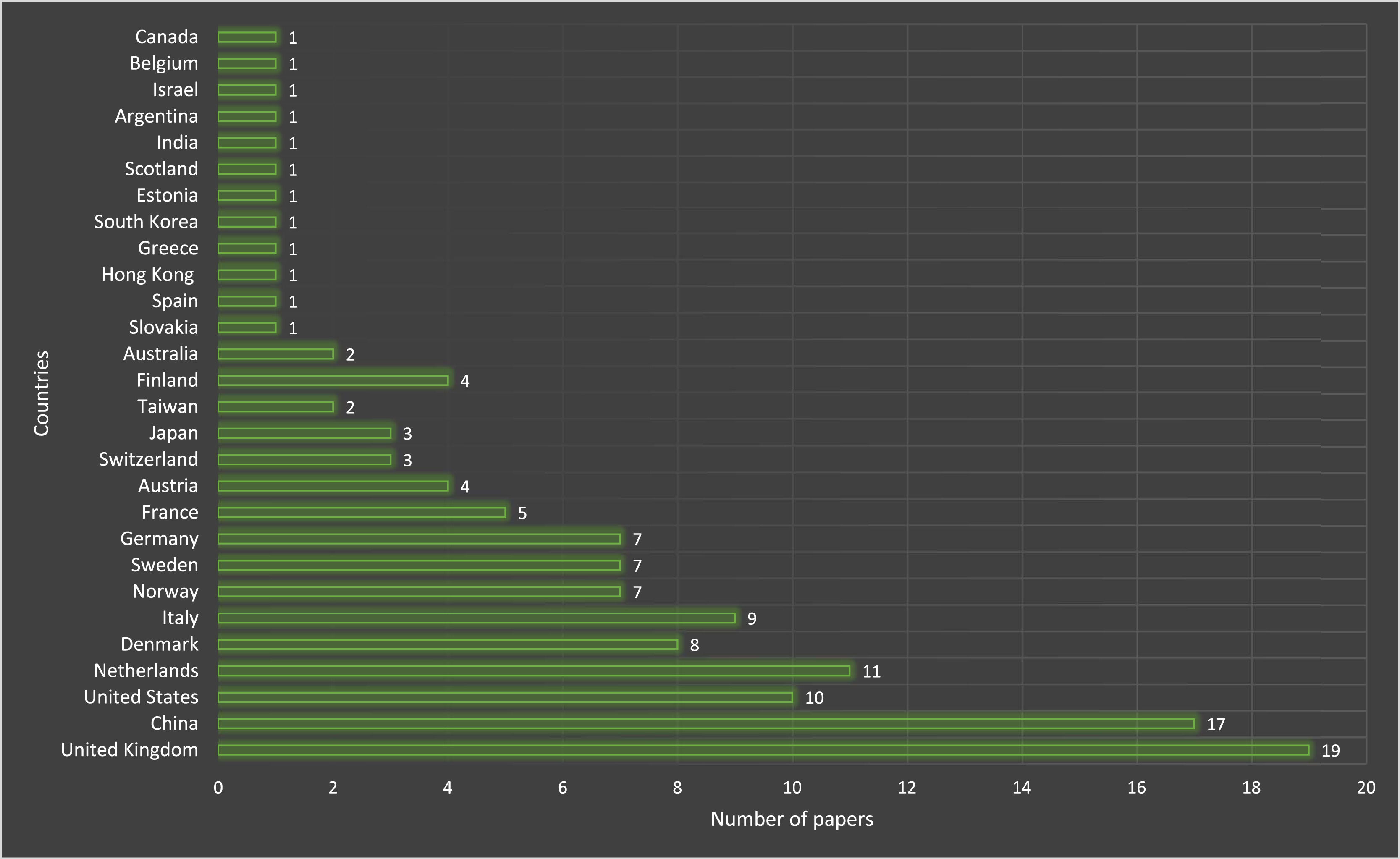

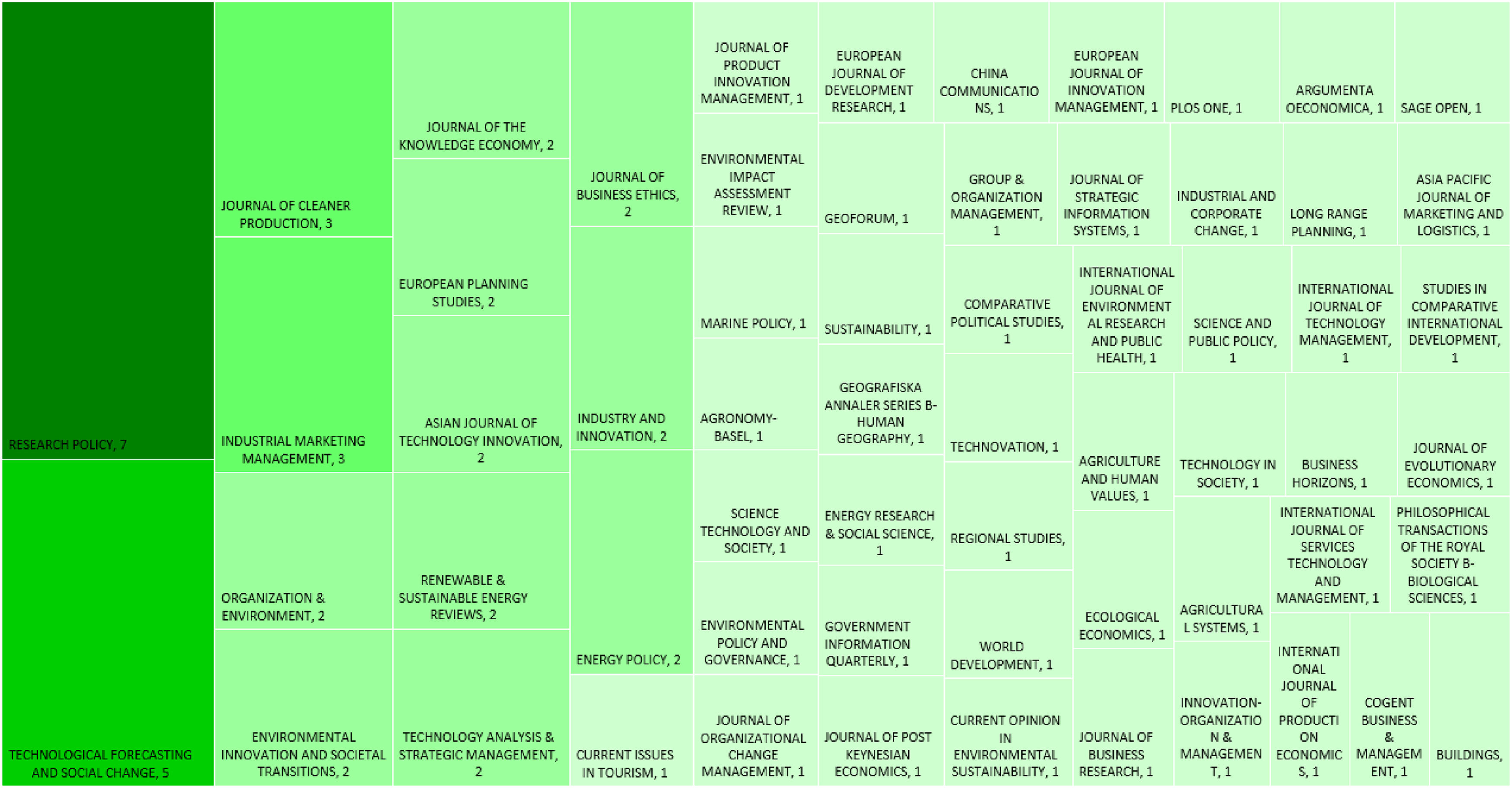

The selected articles were published from 2002 to 2025 by authors with affiliations across 29 countries, most often the United Kingdom, China, the United States, and the Netherlands (see Appendix B). An analysis of the authors’ institutional affiliations revealed a strong research orientation toward innovation systems, entrepreneurship, and technology management, usually in departments of business administration, economics, and management. Several contributors were also noted as specializing in environmental management, sustainable innovation, and corporate sustainability, often in the context of energy transitions. The disciplinary spectrum also included economic geography, urban and regional planning, behavioral strategy, decision-making, project and construction management, information technology, and financial services. A smaller subset of authors was noted to be affiliated with sociology, human geography, and political science.

Research fieldThe results of the review show that within the scope of the research presented, there has been a strong focus on technological innovation (e.g., in information and communications technology, digital technology, medical and health technology, and renewable energy technology) and sustainability. Many researchers have explored both traditional and emerging industries (e.g., agriculture and food production, textiles, and apparel) as well as examined the impact of industrial clusters in different sectors (e.g., Shaoxing textile cluster and the Wenzhou low-voltage electrical appliance cluster). Considering the geographical scope of the studies presented, Europe featured prominently, with countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Italy, Finland, and Austria focusing on areas such as wind energy, renewable energy, and automotive industries. Asia, particularly China and Japan, was also represented well in the sample, with research strongly focused on information and communications technology, high-tech industries, renewable energy, and large companies such as Alibaba, Tencent, and United Microelectronics Corporation. The United States appeared in relation to sectors including solar power, the automotive industry, and renewable energy systems. A significant share of the research was dedicated to business impacts on environmental sustainability, while less represented were articles delving into societal change and political science. A detailed overview of the scope of the research across the selected articles appears in Appendix C.

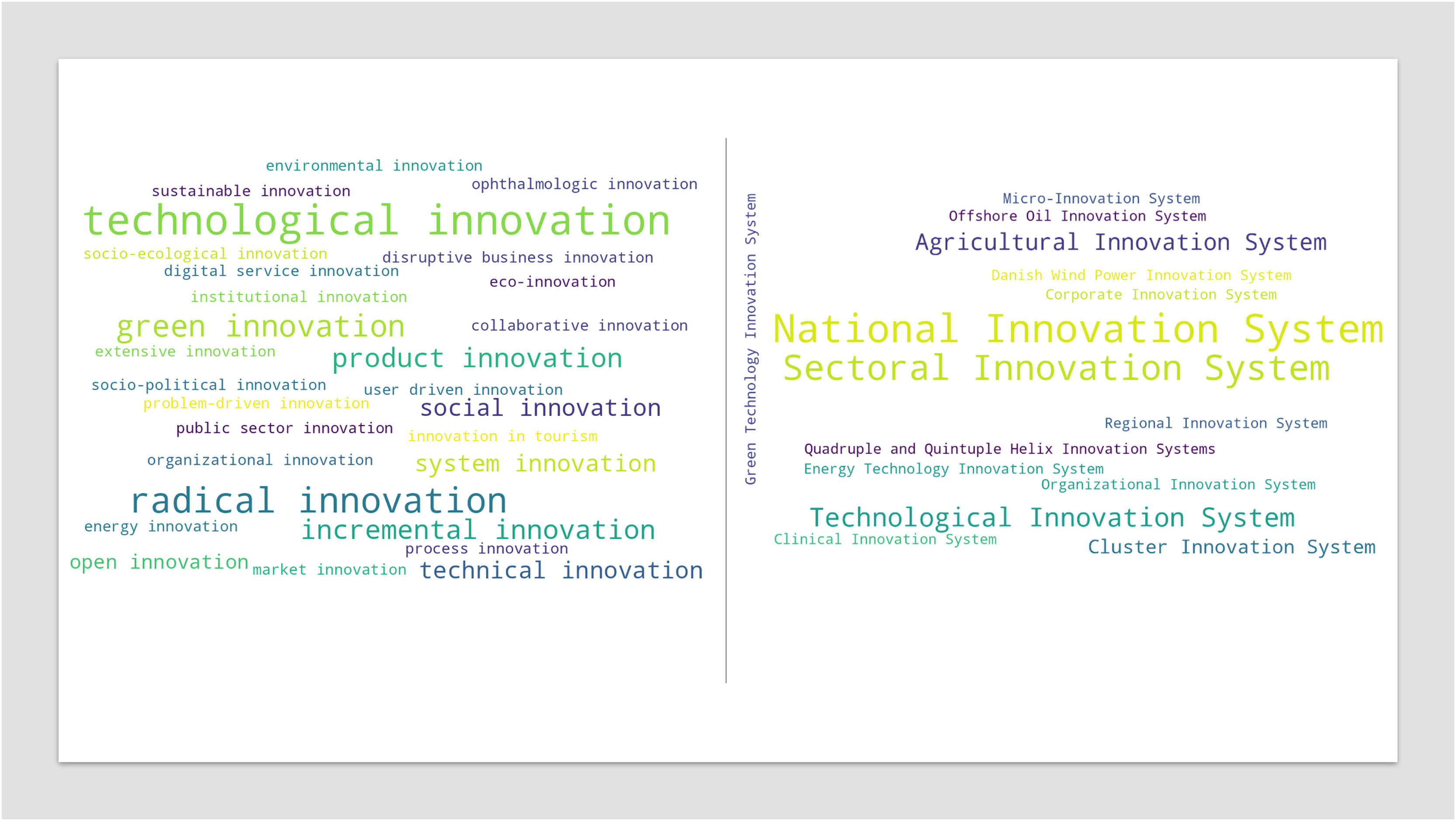

We also analyzed dominant patterns of categorization in the literature by identifying the most frequently discussed types of innovation and the most commonly defined boundaries of innovation systems (Fig. 5).

The most frequently discussed types of innovation in the articles included technological and green innovations, often viewed as catalysts for broader systemic changes reflected in institutional transformations across various levels (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018; De Laurentis, 2015; K.-J. Lee, 2012). When considering the impact on existing processes and relationships, authors have commonly differentiated between incremental and radical innovations. Institutional innovations, meanwhile, have been regarded as integral to many innovation processes (Kilelu et al., 2013) due to driving changes in established routines (Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018) and fostering developments such as corporate (Xiang & Jiang, 2023) and organizational innovations (Bach & Stark, 2002; Mikheeva, 2019). From a broader viewpoint, institutional innovations have overlapped with social innovation (Sarkki et al., 2022), which is closely linked to systems innovation and emphasizes simultaneous institutional changes at various levels (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018; De Laurentis, 2015), the latter being viewed by some authors as a “co-evolutionary process” (Geels, 2005, p. 682).

When defining the boundaries of innovation systems, scholars have commonly adopted either geographical or functional perspectives. Geographically, the focus has been national innovation systems (Fagerberg et al., 2009; Lema et al., 2018; Sæther et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2009); functionally, it has often been technological innovation systems (Gong & Hansen, 2023; Jordaan et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2020; Quitzow, 2015; van der Loos et al., 2021). Considerable attention has also been given to sectoral innovation systems (Galbrun & Kijima, 2009; Jin & McKelvey, 2019), in which the role of specific industries becomes central. Examples include offshore oil systems (Dantas & Bell, 2011), as well as wind power (Gregersen & Johnson, 2009), clinical (Galbrun & Kijima, 2009), and agricultural innovation systems (Kilelu et al., 2013). In parallel, many scholars have described innovative environments without explicitly using the term “innovation system” but have instead referred to sociotechnical or socioecological systems. The concept of ecosystems seems to be increasingly adopted in the literature, often in reference to business ecosystems, innovation ecosystems, or industrial ecosystems (Breslin et al., 2021; Engelberts et al., 2021; B. Liu et al., 2022; G. Liu & Rong, 2015; J. Liu et al., 2022).

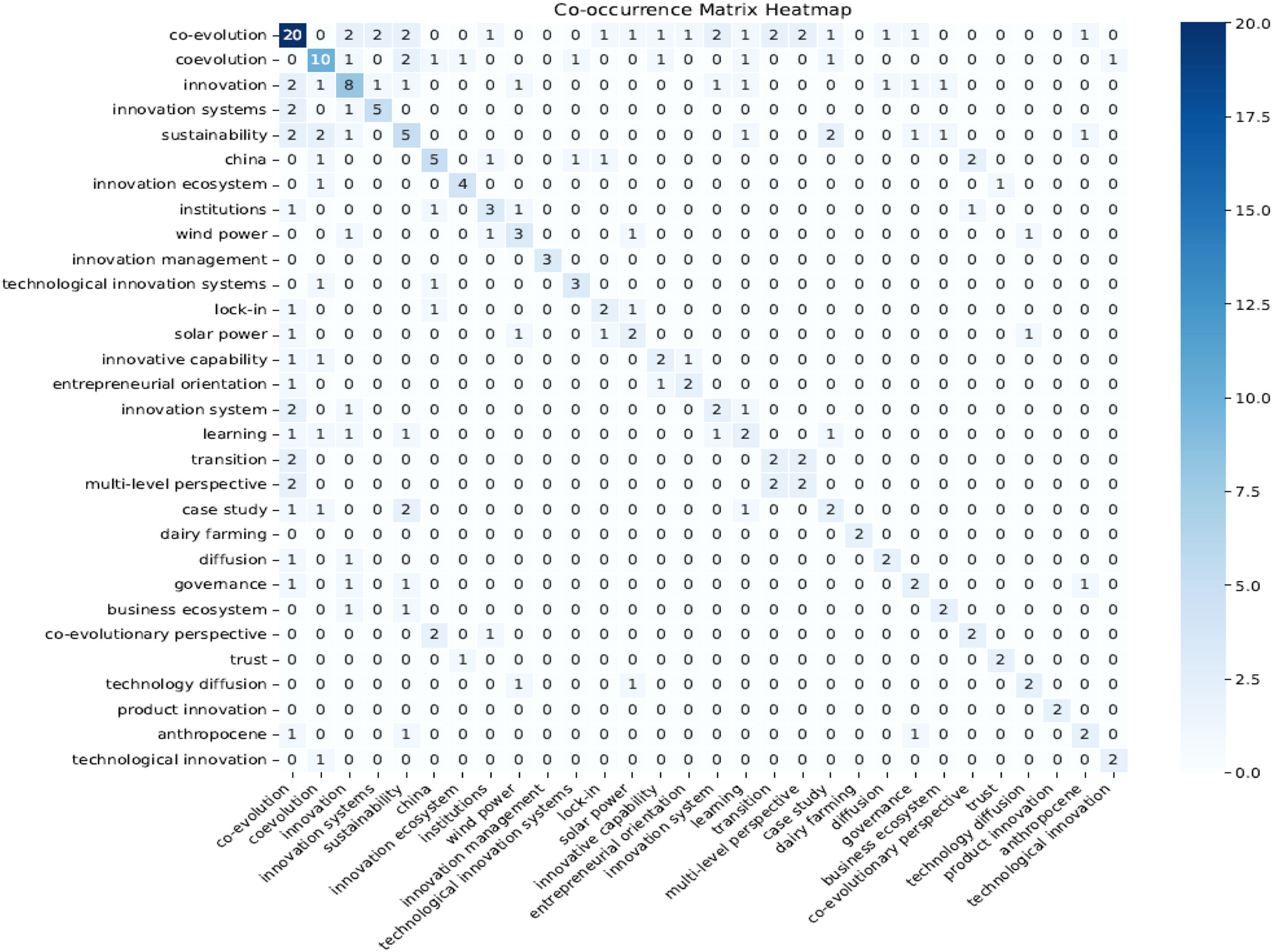

To gain deeper insight into the research scope, we conducted a co-occurrence analysis based on a dataset of keywords extracted from the articles reviewed. To ensure clarity and reduce visual noise, we applied a frequency threshold of 30, meaning that only keywords appearing at least 30 times in the dataset were included. A co-occurrence matrix was subsequently generated by counting how often keyword pairs appeared together. The matrix was visualized in two formats: a heatmap (see Appendix D), with color intensity representing the frequency of co-occurrence between pairs of keywords, and a network graph (Fig. 6), with nodes representing keywords and edges indicating non-zero co-occurrence values. Edge thickness and color intensity were scaled according to the frequency of co-occurrence using a blue color scheme with lighter tones for weaker connections and darker ones for stronger connections. A force-directed spring algorithm was used to enhance the graph’s spatial organization by positioning highly connected keywords closer together for improved interpretability. Isolated nodes without links were excluded to maintain visual clarity.

The network graph showcases several prominent nodes and clusters that illustrate the underlying thematic structure of the research scope. Central keywords such as “co-evolution,” “innovation,” “innovation systems,” “multilevel perspective,” “transition,” and “sustainability” appear as core concepts, which indicates their pivotal role in the scholarly discourse. Notably, “case study” also appears as a highly connected node, which reflects the prevalence of qualitative, context-specific methodological approaches. The analysis also revealed a clear dominance of a technological orientation, as evidenced by frequently occurring keywords such as “technology diffusion,” “technological innovation,” and “technological innovation system.” Those terms are clustered closely with domain-specific applications such as “solar power” and “wind power,” which are themselves strongly associated with broader themes such as “transition,” “multilevel perspective,” and “sustainability.” A thematic linkage can be observed between the terms “institutions,” “lock-ins,” and “trust,” which suggests a recurring interest in institutional barriers to change and the role of social dynamics in shaping trajectories of innovation.

Analysis of applied methodologiesMost articles present empirical research, with a few exceptions dedicated to literature reviews (Aarikka-Stenroos & Ritala, 2017; della Porta & Tarrow, 2012; Fagerberg et al., 2009; Jordaan et al., 2022; Lema et al., 2018; Nuutinen et al., 2024; Wickramaarachchige et al., 2024). In many cases, literature analysis was a preliminary step for qualitative empirical research, often accompanied by methods such as content analysis (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018; Miyao, 2021) or meta-analysis (Li et al., 2022). Those methods, in turn, were frequently combined with document analysis, archival data analysis, and reviews of industry reports, news, market studies, and online forums (Driessen & Heutinck, 2015; Giones & Brem, 2017; K.-J. Lee, 2012). Quantitative methodologies, employed less frequently, involved methods such as agent-based models (Dijk et al., 2013), panel cointegration analysis (Castellacci & Natera, 2013), evolutionary game method with replicated dynamic equations (Yi et al., 2024), evolutionary stable analysis, game theory models, numerical simulations (B. Liu et al., 2022), parametric hazard models (Talay et al., 2014), fixed-effects regressions (Hu & Zhang, 2023), and linear proportional methods integrated with spatial and temporal analysis (Liang et al., 2020).

In most articles, the research followed qualitative empirical methods, with various types of case studies being the most commonly applied method (Chen et al., 2022; Fang & Wu, 2006; Galbrun & Kijima, 2009; Gong & Hansen, 2023; Holgersson et al., 2018; Leszczyńska & Khachlouf, 2018; J. Liu et al., 2022; Mikheeva, 2019; Morgan et al., 2018; Pilloni et al., 2020; Rycroft & Kash, 2002; Zhu & Pickles, 2016). Those case studies were frequently supported by primary data collection including semistructured or in-depth interviews (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018; Engelberts et al., 2021; Jin & McKelvey, 2019; Lindfors & Jakobsen, 2022; G. Liu & Rong, 2015; van der Loos et al., 2021), focus groups and other participatory methods (Kilelu et al., 2013; K.-J. Lee, 2012; Taylor et al., 2013), and observations (Innis et al., 2024; Leszczyńska & Khachlouf, 2018). The diachronic case study was another approach used in that context (Yongsheng et al., 2021). Longitudinal methods were also commonly used in case studies, often combined with historical overviews or time-sequence data (Dantas & Bell, 2011; Hendricks et al., 2025; Hoppmann, 2021; Jiang et al., 2023; Nuutinen et al., 2024; Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018; Sarkki et al., 2022; Scupola & Zanfei, 2016; Yongsheng et al., 2021), which explains the importance of comparing changes over time when analyzing co-evolutionary processes (Hu & Zhang, 2023). Only a few studies applied mixed methods, which generally integrate both qualitative and quantitative data (Blankenberg & Buenstorf, 2016; Leitner, 2015; Metcalfe et al., 2005). A variety of theoretical frameworks were employed as the conceptual foundations for describing co-evolutionary processes within innovation systems (Table 1).

Theoretical and conceptual backgrounds across the reviewed articles.

| Theories applied | Articles |

|---|---|

| 1 Evolutionary perspectives | |

| Evolutionary economic geography | Lindfors and Jakobsen (2022), Paniccia and Leoni (2019), Plechero et al. (2021), Zhu and Pickles (2016) |

| Evolutionary economics | Geels (2014), Jin and McKelvey (2019), Tsai et al. (2009) |

| Evolutionary game theory | Hao et al. (2022), Holgersson et al. (2018)(Hao et al., 2022; Holgersson et al., 2018) |

| 2 Systems thinking frameworks | |

| Complex adaptive systems | Leitner (2015) |

| Bertalanffy’s general system theory | Liang et al. (2020) |

| Transformation toward sustainability theory | Ma et al. (2018) |

| Sociotechnical transitions | Kemp & van Lente (2024) |

| 3 Institutional and Organizational Foundations | |

| Institutional taxonomy (e.g., North’s taxonomy of institutions and Hartley’s model) | Chlebna and Simmie (2018), Scupola and Zanfei (2016) |

| Organizational ecology | Liu and Rong (2015), Miyao (2021) |

| Institutional economics | Sæther et al. (2011) |

| 4 Complementary theoretical lenses | |

| Ground theory | Fang and Wu (2006) |

| Resource dependence theory | Hoppmann (2021) |

| Actor–network theory | Geels (2006) |

| Business ecosystem innovation theory | Ma et al. (2018) |

| Value chain theory | Lema et al. (2018), Yin et al. (2021) |

| Zucker’s theory of trust | Kaniadakis and Foster (2024) |

A common conceptual basis was the multilevel perspective framework (Geels, 2005; Pilloni et al., 2020; Sæther et al., 2011), along with paradigms and approaches related to the theory of technology, including sociotechnical systems (Dijk et al., 2013; Epicoco, 2021; Lundvall & Rikap, 2022; Quitzow, 2015; Taylor et al., 2013; van der Loos et al., 2021). Some studies applied conceptual frameworks for describing interactive processes within systems, including evolutionary processes such as growth, replication, and mergers (Schaltegger et al., 2016) and competitive processes such as the Red Queen competition (Talay et al., 2014) and the Lotka–Volterra principle (Watanabe et al., 2004).

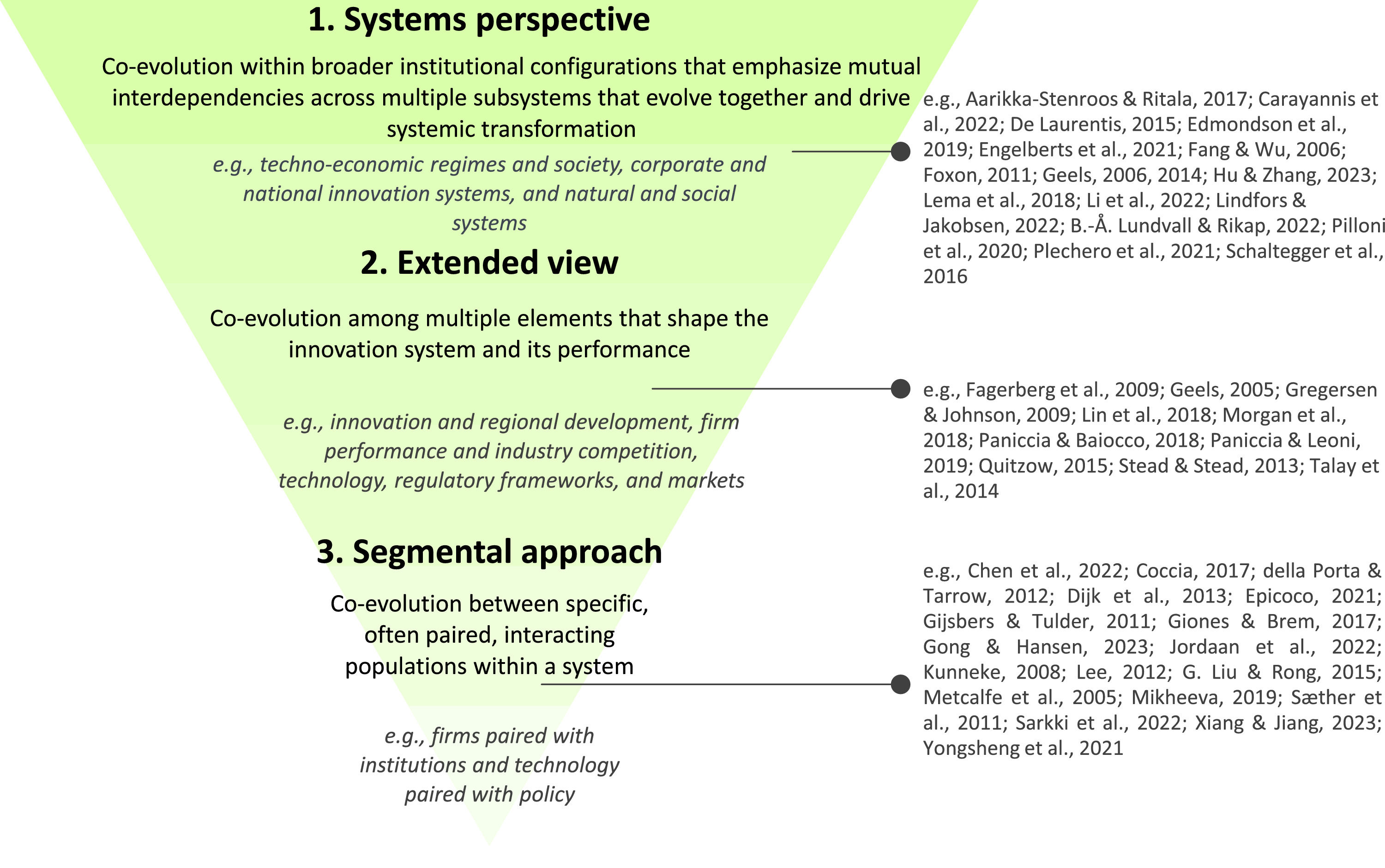

Co-evolution of innovation systemsThe systematic literature review allowed us to identify three major approaches through which authors analyze co-evolutionary dynamics within innovation systems (Fig. 7).

The qualitative synthesis, meanwhile, allowed us to identify a broad range of categories, processes, and patterns that are frequently investigated within the defined perspectives. We structured those elements into three overarching thematic clusters: (1) the co-evolutionary landscape, (2) co-evolutionary dynamics and capacities, and (3) knowledge and learning processes. A consolidated overview of the findings from the systematic literature review appears in Table 2.

Thematic clusters and key nodes in the co-evolution of innovation systems.

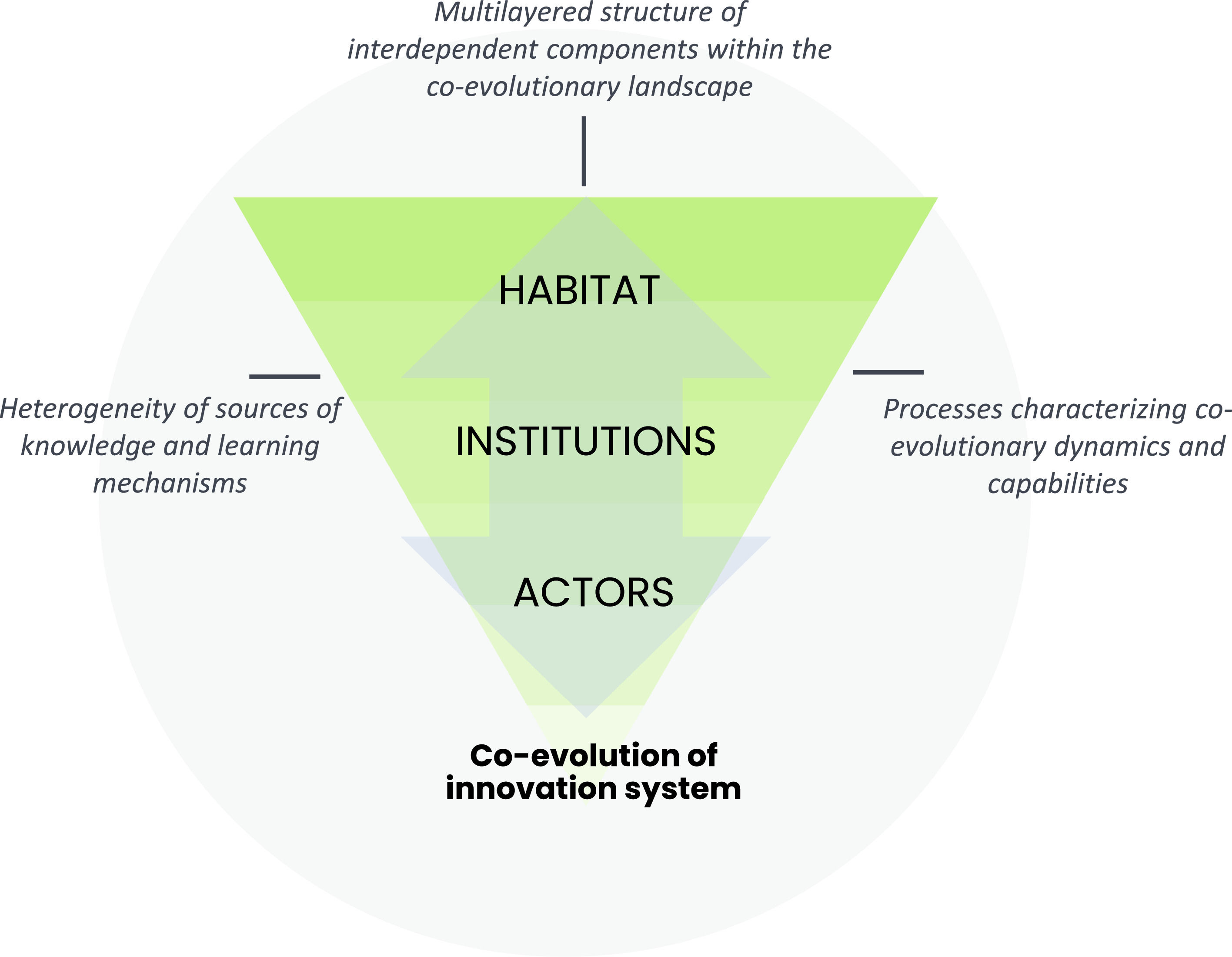

The first thematic cluster highlights the complex, dynamic character of innovation systems, emphasizing their multilayered structure composed of interdependent components. The second thematic cluster concentrates on the core processes characterizing co-evolutionary dynamics within those structural configurations. The third cluster highlights the heterogeneity of sources of knowledge and learning mechanisms that both support and emerge from the co-evolution of innovation systems. Together, those clusters operate simultaneously, driving the co-evolution of complex innovation systems over time. A closer analysis of the thematic clusters (Table 2) reveals three foundational pillars that characterize the complex adaptive structures of innovation systems: institutions, actors, and habitats (Fig. 8). Actors operate within institutional frameworks that shape their behaviors and guide their interactions (Carayannis et al., 2022; Gong & Hansen, 2023; Holgersson et al., 2018; Sarkki et al., 2022). Those frameworks construct institutional “habitats” that not only determine access to resources but also structure learning processes and opportunities (Tsai et al., 2009). The interactions within those habitats play a pivotal role in the creation, transfer, diffusion, and adoption of knowledge across different levels of the innovation system (Galbrun & Kijima, 2009; Lema et al., 2018). Those knowledge dynamics, in turn, reinforce the continuous co-evolution of the system (Fang & Wu, 2006; Leitner, 2015; Lundvall & Rikap, 2022; Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018). Similar to biological systems, innovation systems operate through contradictory, mutualistic, or reinforcing interactions. Those processes shape innovation trajectories and contribute to the emergence or transformation of innovation systems themselves (Geels, 2005). Crucially, co-evolutionary dynamics are foundational to how innovation systems adapt, learn, and transform over time, resulting in both resilient innovation pathways and potential lock-ins. The coexistence of diverse system concepts reflects the dual nature of innovation systems, in which processes of development are inherently intertwined with those of obsolescence (E. D. Lee et al., 2024; Storz, 2008).

Innovation-oriented trajectories develop within underlying innovation systems that are deeply embedded within unique institutional contexts, which themselves are shaped by historical legacies, cultural frameworks, and regional capabilities (Epicoco, 2021; Gong & Hansen, 2023; van der Loos et al., 2021). Those contexts, inherently temporal and spatial, influence how innovation systems adapt and evolve over time (Aarikka-Stenroos & Ritala, 2017). The interaction between innovation systems and their institutional contexts is fundamentally co-evolutionary, with each shaping the dynamics of the other (Scupola & Zanfei, 2016; Su et al., 2020). Among the principal drivers of co-evolutionary dynamics are policy interventions and political ties (Edmondson et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2023; Yin et al., 2021), technological advances (Giones & Brem, 2017), and evolving research agendas (Blankenberg & Buenstorf, 2016; Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018). Policies and different forms of governance are important structural components within innovation systems that affect their overall performance by influencing actors’ interests and capabilities, restructuring networks, and adjusting institutional structures (Gong & Hansen, 2023; Innis et al., 2024). Co-evolution emphasizes the complex, multilayered structure of innovation systems that enables reciprocal influences between co-evolving subsystems across different spatial configurations, including global innovation systems and various national subsystems interconnected through transnational linkages (Quitzow, 2015). Put differently, the institutional context in which innovation systems operate is multilayered and encompasses co-evolutionary connections between, for instance, a region’s industrial structure (e.g., its dominant specializations and knowledge domains) and its organizational configuration, involving government, business, and knowledge-providing organizations (Plechero et al., 2021; Wickramaarachchige et al., 2024). Innovation systems are also characterized by multidimensional causality, such that changes within one subsystem (e.g., an organization or network) emerge from complex nonlinear co-evolution with other subsystems and surrounding environmental conditions (Cristofaro et al., 2024; Yi et al., 2024). As those coevolutionary relationships evolve, the innovation system can be viewed as a complex adaptive system with boundaries that remain open and continuously shift (Breslin et al., 2021).

The multilayered institutional context provides social structures and introduces ever-increasing social complexity and the potential for conflict (Nuutinen et al., 2024; Xiang & Jiang, 2023). Such complexity brings a human dimension into focus, in which social needs, behavioral patterns, and degrees of acceptance either facilitate or hinder the diffusion of innovation (Dijk et al., 2013). Beliefs and perceptions about what is considered to be normal, desirable, acceptable, and sustainable play an important role in co-evolutionary processes (Kemp & van Lente, 2024). For instance, the acts of adopting and diffusing innovation incorporate learning processes that serve both as drivers and as outcomes of the co-evolution between technological and social practices, which may lead to the emergence of new social roles (Pilloni et al., 2020). At the same time, conflicting interactions among different actors may serve as catalysts for innovation via processes of reciprocal adaptation (della Porta & Tarrow, 2012; Sarkki et al., 2022). In that context, the diversity of actors and their social linkages enhance the circulation of knowledge and information, which are critical for innovation processes (Su et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2021). Co-evolutionary interactions among actors are both reciprocal and simultaneous, such that changes in the resources and/or capabilities of one actor provoke adaptive responses in others (Breslin et al., 2021). Actors operate within a landscape shaped by diverse normative frameworks, cultural logics, and institutionally defined identities that influence and guide their behavior (Nuutinen et al., 2024). Furthermore, historical and cultural heritage, often reinforced by cultural traits and spatial proximity, create interdependence among actors and facilitate networking, interaction, trust, and collective learning (Leszczyńska & Khachlouf, 2018; Paniccia & Leoni, 2019; van der Loos et al., 2021; Yongsheng et al., 2021). Cultural context is a crucial factor that influences innovation via social learning and that, within co-evolutionary dynamics, can either facilitate or hinder the diffusion of innovation (Kostis et al., 2018). With a vital role in transmitting knowledge and values, culture impacts not only a community’s cohesion but also its potential engagement in the innovation process (Sica et al., 2025). As detailed by Yongsheng et al. (2021), cultural embeddedness operates within a continuous co-evolutionary feedback loop that also encompasses innovation performance. As a result, positive and negative feedback on innovation performance, influenced by cultural embeddedness, can respectively strengthen or weaken cultural embeddedness itself. That dynamic may generate couplings, in which interactions mutually reinforce development, or lock-ins, in which both sides become resistant to change.

Last, resource dependence is a critical aspect of co-evolutionary dynamics within innovation systems (Hoppmann, 2021). An innovation system’s ability to access and allocate resources prompts its adaptation to a specific development pathway, which influences how knowledge flows are configured within the system. In turn, the evolving innovation system influences the availability of resources, which reinforces the dynamic feedback loop (Hao et al., 2022).

Co-evolutionary dynamics and capabilitiesInnovation typically emerges from the confluence of multiple, simultaneously active forces (K.-J. Lee, 2012; Leitner, 2015; Su et al., 2020). Those complex co-evolutionary processes link various actors through mutual relationships that create interdependencies within a multilayered, multidimensional institutional context that cultivates the emergence and development of innovation systems (Blankenberg & Buenstorf, 2016; Paniccia & Leoni, 2019). Such systems may emerge, for instance, through the co-evolution of market niches and industrial priorities with policy interventions that foster new technological and market opportunities (Jin & McKelvey, 2019). The institutional context also positions innovation systems within a dynamic, interconnected structure in which co-evolutionary interactions continuously generate, shape, and redefine innovation trajectories and ultimately drive transformation, development, and/or emergence of new innovation systems (G. Liu & Rong, 2015; Miyao, 2021; Taylor et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2009; Zhu & Pickles, 2016). Another example is the emergence of new, related industries—for example, cell-based seafood production—that can evolve latently within the existing industrial environment. In such cases, technology, competencies, resources, and practices spill over from established sectors, which showcases the co-evolutionary interconnectivity between established and emerging industries (Lindfors & Jakobsen, 2022).

Co-evolutionary processes often induce various forms of path dependency, wherein systems such as industries and regional economies, are marked by inertia (Sæther et al., 2011). The interactions between agents and institutions is central to shaping trajectories of innovation as well as in forming path dependencies (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018). For example, national innovation systems may act as environments for entrepreneurial ventures where path dependency influences which ventures are supported. As a result, ventures that diverge from dominant economic sectors may find the system poorly adapted to their needs, for policies and institutions often provide limited support to new, knowledge-intensive sectors (Fagerberg et al., 2009). However, path dependencies also extend beyond economic structures and include sociocultural, infrastructural, and regulatory dimensions, among others, that are deeply embedded in institutional contexts and can shape the conditions for innovation (Geels, 2005). Path dependencies can produce lock-ins across multiple dimensions of an innovation system, which hinders its adaptability and constrains the adoption and diffusion of innovations (Hoppmann, 2021; Sæther et al., 2011; Yongsheng et al., 2021). As a result, co-evolution within innovation systems is frequently marked by tensions and, at times, conflicting dynamics (Kilelu et al., 2013). Such volatility underscores the value of a historical, systemic perspective in analyzing innovation systems (Sæther et al., 2011).

Co-evolution within innovation systems is driven by a complex interplay of competitive and cooperative interactions among diverse actors that shape the overall dynamics of the system (Holgersson et al., 2018; Sarkki et al., 2022; Watanabe et al., 2004). Those actors engage in various symbiotic relationships through networks of interaction in which multilateral collaboration and mutual influence are essential (B. Liu et al., 2022). Similar to the symbiotic relationship between bees and flowers, mutualistic co-evolution involves interactions that generate mutual benefits—for example, when suppliers and manufacturers co-develop value propositions, enhance each other’s innovation processes, and, as a result, strengthen their competitive advantages (Cristofaro et al., 2024). Although innovation systems are often viewed as collaborative structures, they also involve strategic competition among actors (B. Liu et al., 2022). For example, industries function as communities of coevolving firms united by a shared vision for innovation, and similar to traditional predator–prey interactions, they develop strategies to compete and to cooperate—in other words, strategies “to eat” and strategies “to avoid being eaten” (Stead & Stead, 2013, p. 166). Collaborative efforts play a vital role in activating co-evolution within the innovation system while creating value and laying the groundwork for subsequent innovations (G. Liu & Rong, 2015; Watanabe et al., 2004). At the same time, different forms of competition serve as powerful co-evolutionary forces within innovation systems. Just as a struggle for survival in ecological systems, co-evolutionary relationships in innovation systems reveal the interdependence among actors who collectively deliver value (Breslin et al., 2021). Competition is often associated with so-called creative destruction, in which emerging organizational forms disrupt existing industrial competencies (Fang & Wu, 2006). Drawing from evolutionary biology, the Red Queen hypothesis is used to illustrate such competitive dynamics. Per the hypothesis, when a firm introduces a radical or incremental innovation, it gains a competitive advantage, which urges rivals to innovate in turn, thereby initiating a continuous feedback loop of escalating rounds of innovation that gradually weed out weaker players from the market (Talay et al., 2014). A similar form of antagonistic co-evolution can occur between indirectly competing actors—for example, a mainstream market incumbent and a niche market startup—in which the incumbent seeks the startup’s elimination through acquisition, while the startup counters with innovative technology, strategic alliances, and/or legal safeguards to protect itself from takeover (Cristofaro et al., 2024). To preserve dominant market positions, some players also engage in anti-competitive or even predatory actions that weaken competitors but ultimately harm consumer welfare (Lin et al., 2018; Mikheeva, 2019).

Organizational adaptation is another essential co-evolutionary process within innovation systems (Fang & Wu, 2006), one that involves mechanisms of mutual adaptation that reflect dynamic interactions across multiple levels that vary in their intensity, causality, and influence (Jiang et al., 2023). Organizational adaptation is largely shaped by interdependencies and interactions between an organization’s competitive power and environmental pressures that shift over time (Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018). For instance, institutions operating at different levels may co-evolve in response to external shocks, which enhances the adaptive capacity of the system as a whole (Zhu & Pickles, 2016).

Co-evolutionary dynamics are fundamental to shaping transformation capacities both within and across different levels of innovation systems, including between companies and national innovation systems (Foxon, 2011; Geels, 2006; Hu & Zhang, 2023; Ma et al., 2018; Schaltegger et al., 2016). Innovation acts as a catalyst for structural change (Epicoco, 2021), while transition pathways help to identify the drivers of and barriers to the adoption and diffusion of those changes that are deeply embedded within the institutional context (De Laurentis, 2015; Pilloni et al., 2020).

Knowledge and learning processesAn innovation system’s competitiveness largely depends on continuous co-evolution between diverse forms of knowledge and innovative activities (Carayannis et al., 2022; Lundvall & Rikap, 2022; Sæther et al., 2011). Institutions play a vital role in nurturing those processes by establishing the conditions that support various modes of learning and forms of collaboration within the system (Dantas & Bell, 2011; Galbrun & Kijima, 2009; Gregersen & Johnson, 2009; Kilelu et al., 2013). Developing knowledge is an evolutionary as well as adaptive process rooted in historically shaped institutional relationships that co-evolve alongside the creation and application of knowledge, which ultimately forms distinct trajectories of innovation (Chlebna & Simmie, 2018; Metcalfe et al., 2005).

Innovation draws on diverse forms of knowledge, including scientific, experiential, and indigenous knowledge (Fang & Wu, 2006; Galbrun & Kijima, 2009; Kilelu et al., 2013). Equally important is individual knowledge and its diffusion within relevant communities, which fosters a shared understanding of problems. Through co-evolutionary processes, informal communities cultivate new forms of collaboration that give rise to emerging collectives and evolving formal and informal rules that reshape patterns of inclusion and exclusion as well as participation and representation and ultimately influence the future development of underlying systems (Innis et al., 2024). Scholars have underscored the importance of social and cognitive proximity, which co-evolve along with innovation outcomes through interactive learning dynamics that often define patterns of sectoral specialization (Leszczyńska & Khachlouf, 2018). Knowledge emerges through network relationships, including between firms, universities, research institutions, and other actors across the value chain (Lema et al., 2018; Yongsheng et al., 2021). Co-evolution processes within knowledge networks enhance the collective generation, acquisition, and integration of diverse forms of knowledge and capabilities essential for innovation. In that context, discourse is an important force in co-evolution that shapes new community-based practices and challenges established norms within participating communities, thereby facilitating the integration of knowledge and, in turn, strengthening innovation systems (Nuutinen et al., 2024). Co-evolutionary interactions between science and industry, for instance, facilitate the transfer of knowledge that shapes innovation dynamics as well as financial resource dependencies (Hoppmann, 2021). Within those networks, trust plays a critical role by shaping the willingness to share knowledge, which enhances collaboration and improves access to strategically valuable knowledge-intensive resources (Kaniadakis & Foster, 2024; Yongsheng et al., 2021). Those collective learning processes, shaped by interactions between actors, strengthen collective engagement and value co-creation, which enables innovation systems to adapt dynamically in response to broader transformational goals (Hendricks et al., 2025; Nuutinen et al., 2024).

The long-term development of innovation systems is closely linked to the co-evolution of innovative and absorptive capacities (Castellacci & Natera, 2013). Absorptive capacity, or the ability to identify and apply acquired knowledge, is particularly crucial in supporting co-evolutionary processes (Castellacci & Natera, 2013; Fagerberg et al., 2009; Lema et al., 2018). For example, firms with greater absorptive capacity benefit from internal bases of knowledge and greater cognitive proximity to external sources, which facilitates effective engagement with both local and global knowledge networks (Xiang & Jiang, 2023). Furthermore, policy interventions play a vital role by providing new channels for knowledge diffusion that aid in identifying the opportunities and limitations of national innovation systems when seeking to integrate into international knowledge sharing (Castellacci & Natera, 2013; Lema et al., 2018; Plechero et al., 2021).

DiscussionFrom complex adaptive systems to collaborative learning environments and systems interventionsAn important contribution of our systematic literature review lies in the interconnectedness of the guiding hypotheses of our research. On that count, instead of treating each hypothesis in isolation, the literature demonstrates how they collectively articulate a vision of innovation systems as complex adaptive structures that function as a collaborative learning environment in which interactions form a system of relations that shape distinct dynamics of innovation. In that regard, the collaborative learning environment extends the conceptual lens of a complex adaptive system into an analytical framework, one that allows the assessment of conditions that influence processes of innovation, informs strategic decisions, and evaluates potential impacts. For instance, the effectiveness and long-term viability of innovative interventions cannot be understood from the vantage point of a single actor or institution. Interventions, as goal-oriented processes tied to specific objectives and/or interests, are embedded within the innovation system, wherein knowledge and learning processes each play a dual role as analytical instruments for managing the heterogeneity of knowledge and tools for enabling collaboration, dialogue, and capacity building among the agents involved. By fostering shared understanding and mutual learning, those processes transform the collaborative learning environment into an applied mechanism that generates meaningful social impact by supporting the co-creation and implementation of innovation strategies and systems interventions. As such, innovation systems operate simultaneously across conceptual, analytical, and applied dimensions (Fig. 9), which reinforces their identity as learning-oriented structures. Similar to the principles of second-order cybernetics (von Foerster, 2003), they maintain a continuous feedback loop between systems interventions, societal impacts, system dynamics, and learning processes.

Innovation systems across scales: Structure, hierarchy, and transformationThe hierarchical organization of innovation systems is particularly significant because it determines how knowledge is generated, disseminated, and used to develop the capacity for innovation at different scales. Those systems encompass various nested levels, from individuals and groups to organizations and national, regional, continental, and global systems (Satalkina & Steiner, 2020; Steiner, 2017). The findings of our systematic literature review highlight that innovation systems can be conceptualized and analyzed across multiple levels, ranging from the regional and sectoral to the organizational (Geels, 2005; Metcalfe et al., 2005; Rycroft & Kash, 2002). That multilayered configuration mirrors the typical structure of human systems found in socioecological models (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) and nested hierarchical levels (Miller, 1978). By differentiating the hierarchical levels in innovation systems, it becomes possible to systematically analyze how macro-level dynamics (e.g., economic growth), meso-level transformations (e.g., institutional or sectoral restructuring), and micro-level behaviors (e.g., decision-making of individual actors) interact and co-evolve (Dopfer et al., 2004; Fritsch et al., 2019; Gong & Hassink, 2019). The hierarchical dimensions of innovation systems are essential in defining functional boundaries and mapping potential trajectories for up- or downscaling the effects of targeted interventions. Those trajectories are further influenced by various supportive conditions, including historical legacies, economic structures, and sociocultural values (Binz & Truffer, 2017; Coenen et al., 2012). Therefore, beyond hierarchy, the structural dimensions of innovation systems also encompass the broader systemic environment, including sociocultural contexts, economic and financial conditions, technological developments, ecological factors, built infrastructures, and political, legal, and institutional arrangements (Satalkina & Steiner, 2020).

Innovation is shaped by the nature of interactions not only between actors and other actors but also between actors and the broader institutional environment (Duarte & Carvalho, 2024). Within those co-evolutionary dynamics, innovation systems often undergo reconfiguration as a result of shifts that transcend established spatial and/or sectoral boundaries (Coenen et al., 2012; Schot & Geels, 2010). Therefore, some scholars have extended the analytical lens of innovation processes to encompass interactions between humans and animals (Driessen & Heutinck, 2015) and even broader sociotechnical systems (Cooke, 2012; Geels, 2006; Pilloni et al., 2020; Y. Zhang, 2020). Given the central role of knowledge within innovation systems (Lundvall, 1985; Lundvall et al., 2002) and the understanding that learning is a predominantly “socially embedded process” (Lundvall, 1992, p. 1), innovation systems are inherently intertwined with broader social systems in their co-evolution (Espinosa-Gracia & Sánchez-Chóliz, 2023) and all the attendant social and cognitive complexities (Young, 2022). Those processes, in engaging diverse agents across hierarchical levels, create a fluid co-evolutionary structure within and between different layers of the system (Fang & Wu, 2006; Leitner, 2015; Lema et al., 2018; Lundvall & Rikap, 2022; Paniccia & Baiocco, 2018). They evolve through continuous dynamic interactions among social institutions (Lenski, 1984, 2005; Nolan & Lenski, 2011; Weber, 1947) and agents who co-create and exchange knowledge across various levels of the system (Geels et al., 2018).

Hierarchy within innovation systems is not merely a structural feature but also delineates responsibilities, competences, and the potential for impact. At the same time, it reveals the risk of tensions and conflicts between different levels, particularly when individual and collective rationalities diverge (Scholz, 2011). The risk becomes especially relevant regarding innovation strategies aimed at systemic transformation. In that context, systems innovations are seen as interventions shaped by networks of actors operating across various spatial and institutional scales and promoting cross-boundary collaboration to address complex societal and systemic challenges (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2015). The consolidated view on systems innovation has been extensively outlined by Midgley and Lindhult (2021), who highlight its complementarity with other forms of innovation and its potential to drive collaboration. Systems innovation creates value, especially when accompanied by complementary innovations (Takey & Carvalho, 2016). In that process, social innovation plays a pivotal role as a driver for transforming social systems and redefining human–environment interactions and, as such, can be understood as an intervention aimed at structural change within the social dimension that, across various contexts (e.g., technological, business, and organizational), targets systemic improvement in society (Satalkina & Steiner, 2022). When addressing the impact of innovation on transitions to more sustainable, resilient societies, researchers have stressed the importance of value creation (DiVito et al., 2021; Lüdeke‐Freund, 2020). However, defining societal needs remains complex, for different stakeholder groups—individuals, communities, businesses, and policymakers—often perceive them differently. Therefore, systems innovations require collaboration and knowledge exchange across multiple domains, including science, markets, policy, and public engagement (Felt, 2020; Jasanoff, 2003; Jasanoff & Kim, 2015; Pfotenhauer & Jasanoff, 2017). In that sense, systems innovation not only enhances processes of collaborative innovation but can also act as a catalyst for establishing or strengthening innovation systems themselves (Midgley & Lindhult, 2021). However, for such innovations to be effective, they require methodological approaches that not only support an understanding of stakeholder dynamics but also promote systems thinking and coordinated action. In that light, systems innovation is increasingly understood as a phenomenon that can be enhanced by systems modeling and hosting dialogues between stakeholders, both of which facilitate social learning and support the development of a shared perspective on the opportunities and consequences of innovation (Colvin et al., 2014; Midgley & Lindhult, 2021; Satalkina et al., 2022).

Bridging perspectives in innovation systems: Knowledge integration, system dynamics, and transdisciplinary learningWithin innovation systems, interactions among actors continuously produce knowledge, which consequently shapes future interactions and fosters ongoing cycles of learning (Breslin et al., 2021; Moallemi et al., 2023). Knowledge thus emerges through bottom-up processes grounded in individual learning and experience, which collectively influence and reshape institutional structures and establish a continuous, iterative feedback loop (Rammel et al., 2007). Within that dynamic, the integration of knowledge becomes a pivotal mechanism; it connects diverse forms and sources of knowledge, as well as perspectives on knowledge, and fosters collaborative learning, bridges disciplinary and sectoral boundaries, and strengthens the adaptive and problem-solving capacities of innovation systems, all of which contribute to societal resilience and competitiveness in the long run (Huang et al., 2025). Designing systems interventions therefore requires a holistic understanding of both the social structures that shape and are shaped by processes of innovation as well as of the transformative effects that those interventions may have on the system. In that way, integrating knowledge bridges analytical frameworks and applied mechanisms of collaborative learning environments, which are structured around shared challenges, targeted interventions, and the co-creation of knowledge.

Individual and social learning depend on the ability of diverse actors to embrace knowledge pluralism—that is, the capacity to engage with multiple forms of knowledge that fosters dialogue, promotes collaboration, and supports a learning-oriented approach to informing and improving interventions (Caniglia et al., 2020; Freeth & Caniglia, 2020). A comprehensive systems perspective involves analyzing its agents and their roles, boundaries, competences, values, and interests. Those factors shape interactions, guide decision-making, and drive system dynamics as both enablers of change and potential barriers to intervention. That approach is essential for understanding what types of innovation-oriented development are needed, appropriate, or feasible within the existing structure of the learning environment, as well as what sort of creative destruction can be possible, necessary, or undesirable. Integrating knowledge from diverse agents fosters a holistic understanding of the system as a whole instead of focusing on its isolated components, as exemplified by the dialectical systems approach described by Mulej and Potocan (2006). When supported by mutual learning, the integration of knowledge becomes a functional mechanism for identifying opportunities for discourse, leveraging synergies, and addressing trade-offs. It facilitates collaboration, helps with navigating conflicts of interest (e.g., corporate priorities versus open innovation and radical versus incremental innovation), and nurtures trust and commitment among key institutions and decision-makers. Put differently, mutual learning serves as a tool for mediation, conflict resolution, and, when possible, the preventive management of conflicts and crises (Steiner, 2025; Steiner et al., 2023). Such alignment with diverse perspectives enhances the viability, societal relevance, and impact of strategies for innovation. In essence, a collaborative learning environment, enabled by the effective integration of knowledge, facilitates consensus building, fosters shifts in social relations and interactions, and supports the co-evolution of societal challenges and strategies for innovation aimed at generating systemic impact.

Strengthening the integration of knowledge requires a robust methodological foundation that embraces diverse perspectives through inclusive communication, dynamic knowledge exchange, and stakeholder engagement. The approach should facilitate meaningful discourse and the co-creation of a shared knowledge base. System dynamics and related modeling approaches (e.g., simulation models, computer-based models, and big data analytics) offer powerful tools for analyzing the behavior of different complex systems and informing evidence-based interventions (Furtado et al., 2015; Prasinos et al., 2022; Süsser et al., 2021). Those tools allow researchers and practitioners to explore nonlinear interactions, feedback loops, and emergent properties that characterize co-evolutionary dynamics of innovation systems. When integrated with genuine stakeholder engagement, modeling becomes a participatory process for collaboratively defining challenges and designing pathways for systems interventions (Moallemi et al., 2021). Such participatory modeling is particularly valuable in cases in which a system’s components and/or interdependencies are poorly defined and when the representation of the situation or problem is unstructured (Moumivand et al., 2022; Novani & Mayangsari, 2017; Tako & Kotiadis, 2015). Although different forms of stakeholder engagement and participation may exist in a modeling process (Voinov et al., 2016, 2018; Voinov & Bousquet, 2010), the challenge is always to ensure the consistent, comprehensive integration of knowledge across different levels and dimensions of the system(s) analyzed. The effective integration of knowledge should occur across disciplinary, sectoral, and institutional boundaries. In particular, transdisciplinary collaboration allows the incorporation of stakeholders’ heterogeneous forms of knowledge and experience from science and practice across different levels of a complex system through extensive discourse. The approach extends beyond conventional participatory methods because it enables continuous collaboration and mutual learning among diverse stakeholders (Norström et al., 2020; Pohl et al., 2021; Scholz & Steiner, 2015). Transdisciplinary modeling incorporates stakeholders’ knowledge directly into the modeling of system dynamics to aid in mapping co-evolutionary interdependencies, explore the behavior of systems, and identify leverage points for potential interventions (Satalkina et al., 2022, 2025). The results of such modeling, in turn, serve as a basis for qualitative conclusions and the development of scenarios. An important advantage of the approach is that the insights derived from such analysis may not be inherently apparent, which makes the approach helpful in analyzing situations with insufficient data for comprehensive modeling assumptions. The results of such modeling have the potential to inform computational models (e.g., agent-based model) and to be applied for their calibration (Moumivand et al., 2022; Novani & Mayangsari, 2017). For instance, emerging science that integrates a soft systems methodology and computational simulation (e.g., system dynamics, discrete-event simulation, and agent-based models and simulations) has been widely used to study complex social phenomena addressing human-driven, coupled systems in fields such as sociology, anthropology, economics, cognitive science, and psychology (Moumivand et al., 2022).

Implications and outlook for future researchThis article’s chief theoretical contribution lies in applying a co-evolutionary lens not only to analyze specific processes within innovation systems but also to conceptualize innovation systems themselves in their complex adaptive nature. Our systematic literature review has provided in-depth insights into the composition and functional processes of the interconnected, dynamic, continuously evolving structure that shapes trajectories of innovation. Building on those foundations, this article has introduced a novel conceptualization of innovation systems as collaborative learning environments: a dynamic, multilevel environment where diverse forms of knowledge are continuously integrated and mobilized. That new framing, in deepening the understanding of innovation systems as learning systems, provides a coherent conceptualization of learning as a mechanism for driving systemic transitions through innovation, in interactive processes that make learning inherently responsive to changing social, institutional, and systemic contexts. That perspective expands the theoretical understanding of innovation systems while offering a bridge to practical applications. Innovation systems are understood as functional mechanisms that support system dynamics through continuous mutual learning, dialogue, and the integration of diverse perspectives. Central to our contribution is the articulation of the triple role of innovation systems (Fig. 9), which illustrates how innovation systems can evolve from theoretical constructs to guiding frameworks for action. That shift emphasizes the need to operationalize innovation systems as tools for enabling systems interventions that generate social impact and ultimately enhance societal resilience and competitiveness. To navigate that transformation, the article has advanced system dynamics and transdisciplinarity as concrete methodological approaches that allow integrating heterogeneous forms of knowledge across scientific, institutional, and sectoral boundaries and that provide structured processes for engaging stakeholders, participating in modeling, and co-creating knowledge. Within that framework, the integration of knowledge becomes a pivotal principle for analyzing complex systems, supporting evidence-informed decision-making, and designing pathways for strategic interventions. By embedding the integration of knowledge into a dynamic learning process, the article has outlined a trajectory from systems analysis to systems intervention that supports the co-creation of innovative solutions through joint value creation. In that light, innovation is viewed not only as an outcome of a learning process but also as a catalyst for reconfiguring institutional and social structures.

Building on the theoretical and practical implications of our research, several key directions for future inquiry emerge, as described below.

Innovation systems as functional frameworks. Future research should deepen the conceptual and empirical understanding of innovation systems as practical mechanisms, not just theoretical constructs. Our systematic literature review has highlighted innovation systems as complex adaptive systems that are embedded in and co-evolve with societal structures. By extension, a critical avenue for further inquiry lies in advancing the conceptual role of collaborative learning environments in shaping sustainable transitions, which includes understanding how such environments can be navigated, managed, and modulated to address societal challenges. To that end, the co-evolutionary lens needs to evolve from a conceptual metaphor to a concrete analytical and regulatory tool, as suggested by Kemp and van Lente (2024), for identifying and steering dynamic processes. Particular emphasis should also be placed on systems innovation to explore how that category can be reframed to understand and enhance cross-boundary collaboration geared toward tackling complex systemic problems (OECD, 2015).

Collaboration and governance structures. The literature highlights diverse models of networks that facilitate the integration of knowledge (Rycroft & Kash, 2002) by enhancing proximity, trust, and a sense of community (Lindfors & Jakobsen, 2022; Paniccia & Leoni, 2019; Zhu & Pickles, 2016). To sustain the effectiveness and contribution of collaborative learning environments, it is essential to develop strategies that ensure their continuous operationalization. For instance, challenges persist in identifying the most effective forms and operational strategies of collaboration and network governance to promote the inclusion of stakeholders, establish efficient channels for information exchange, and develop a shared language within innovation networks.

Education and empowerment. Initiating, engaging in, and facilitating collaborative innovation processes requires specific competences among all stakeholders. Within numerous collaborative frameworks, including open innovation and innovation networks (Petraite et al., 2022) and the triple, quintuple, and multiple helix models (Etzkowitz & Zhou, 2018; Lopes et al., 2020; López-Rubio et al., 2022), universities are often viewed as key actors, with science serving as a mediator in processes of innovation. Although universities are frequently recognized for their contributions to research and knowledge creation, their role in education is equally significant as a driver of disseminating and integrating knowledge. The current education and policy agenda highlights the need to move beyond conventional linear approaches by adopting more complex, nonlinear strategies that equip individuals to navigate uncertainty and complexity in today’s interconnected world as it increasingly experiences rapid technological, cultural, economic, and demographic change (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, n.d.; European Commission, 2023). Although some recent studies have explored how shifts in educational practices align with societal transformations (Cain et al., 2024), they rarely confront the core challenge—that is, preparing future decision-makers to understand innovation as a real-life social phenomenon. Much of the research also remains fragmented and focuses separately on learning experiences (Ellis, 2022), the development of innovation-oriented skills (Kresta, 2021), or the adoption of technology (X. Zhang et al., 2023). Education in innovation, however, should empower individuals with a holistic systems perspective that considers the dynamic environments in which they act and encourages critical reflection on their roles, the opportunities and constraints they face, and the broader impacts and ethical implications of their actions. Future research should explore how innovation systems can be translated into applied pedagogical frameworks that promote solution- and problem-based learning, which enables learners to engage in discourse and act as co-creators within real-world processes of innovation. Integrating the innovation system into education goes beyond embedding it as a teaching concept. Indeed, the innovation system should be framed as a dynamic mechanism whose foundational principles and practical methodologies enable learners to recognize themselves as part of a broader setting in which cross-boundary communication that integrates systems, components, and coupled systems, for example, and cross-border communication across national and organizational borders are essential for anticipating and initiating innovations as solution-oriented approaches that are viable within individual and collective strategies for innovation.