Self-efficacy for coping with cancer is a significant factor for cancer survivors’ quality of life, but it has not been examined among individuals with preexisting severe mental health conditions (SMHC). This study compared perceptions of self-efficacy for coping with cancer among cancer survivors with and without precancer SMHC; quality of communication with the oncology team and depressive symptoms as antecedents of self-efficacy; and the mediating role of self-regulation (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) between antecedents and perceived self-efficacy for coping with cancer.

MethodsParticipants were 170 adult cancer survivors with preexisting SMHC and 80 with no SMHC, aged 20–71, and 1–5 years since diagnosis. They filled out questionnaires in a face-to-face meeting. Multigroup path analysis was conducted using structural equation modeling.

ResultsIndividuals with SMHC reported lower self-efficacy for coping with cancer and higher levels of depressive symptoms. In the SMHC group, cognitive reappraisal mediated the association between perceived communication quality and self-efficacy, and expressive suppression mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and self-efficacy.

ConclusionsThe results highlight the deficiency in self-efficacy for coping with cancer in individuals with SMHC, a prominent factor for treatment adherence and quality of life among cancer survivors. Findings suggest self-efficacy may be strengthened via more emphatic and attentive communication with the oncology team and fostering effective emotion regulation strategies.

The prognosis and quality of life for individuals who have survived cancer have advanced substantially in the 21st century.1 Nonetheless, disadvantaged populations frequently have considerably lower quality of life and lower survival rates.2 Individuals with severe mental health conditions (SMHC), including schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and personality disorders,3 constitute such a group. Research has indicated that they are often diagnosed with cancer at more advanced stages and have worse cancer-related outcomes, impaired quality of life, and elevated mortality rates.3,4

Cancer and its treatments cause substantial negative psychological and physical effects for survivors during treatment and for long periods after its completion.5,6 Cancer survivors with preexisting SMHC also deal with psychiatric symptoms that may be exacerbated by stressors7 such as cancer.8 Moreover, individuals with SMHC may be less equipped to cope with cancer, considering reduced personal, interpersonal, and tangible resources due to high unemployment, social stigma, and lack of family support or social connections.7-10 Little is known about reactions to cancer diagnosis and treatment in this cohort, and most evidence has been derived from professional accounts and case studies, not direct accounts from survivors.11

A key predictor of cancer patients’ ability to adapt to the extensive effects of a cancer diagnosis, comply with treatment, and preserve their quality of life is self-efficacy for coping with cancer.12 Bandura defined the construct of self-efficacy as the belief in one’s capacity to practice particular domain-specific skills.13 Accordingly, self-efficacy for coping with cancer pertains to the behaviors and acts of dealing with a cancer diagnosis, treatment, and the transition into survivorship.12 A meta-analysis of 47 studies reported that cancer survivors with a high sense of cancer self-efficacy had confidence in their ability to manage symptoms and emotions related to cancer successfully, lower their depressive symptoms, and achieve better quality of life.12 Although self-efficacy for coping with cancer has not been studied among individuals with SMHC, people with SMHC and type 2 diabetes reported lower diabetes self-efficacy and worse self-care management compared to those with type 2 diabetes only.14

The perception of self-efficacy is shaped by information processing, including information from the environment and self-belief.13 Therefore, communication with the oncology team—including the extent to which empathy, understanding, and trust in the individual’s abilities are conveyed—can influence the perception of efficacy for coping with cancer. Notably, studies have indicated a high prevalence of mental health stigma among healthcare professionals, which may affect the quality of communication, especially by minimizing contact with patients, using patronizing and stigmatizing language, or not attending to patients’ unique needs.15 The few studies that examined oncology professionals’ attitudes toward individuals with SMHC revealed stigmatizing attitudes and communication difficulties.8,11,16 In a study involving interviews with cancer survivors with preexisting SMHC, only a few participants described positive attitudes and communication from their oncology team; most experiences were negative, characterized by a lack of empathy and distant, impersonal, and stigmatizing communication.17

Another factor that affects self-efficacy perceptions is mental health,13 especially depression, which is the most common comorbid psychiatric disorder among patients with SMHC.18 People with depressive symptoms often underestimate their capabilities, distorting perceptions regarding self-efficacy and their sense of control and success in coping with previous events.13 A cohort study with 389,870 cancer patients, including 13,824 with a preexisting SMHC diagnosis, found they experienced elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to patients with no prior SMHC.19 Another retrospective cohort study found increased suicidality among cancer patients who reported a previous SMHC.20

To understand better how these two factors—perceived communication with the oncology team and depressive symptoms—may contribute to cancer self-efficacy, the present study examined the mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. Emotion regulation strategies, as conceptualized by Gross and John,21 refer to processes that individuals employ to influence how they experience and express their emotions. Two main emotion regulation processes are cognitive reappraisal, in which people reinterpret an emotion-eliciting situation to alter its emotional meaning, and expressive suppression, a response modulation that involves inhibiting ongoing emotionally expressive behavior.21 Cognitive reappraisal is often associated with better psychological and behavioral outcomes, including decreased negative emotions and symptoms, whereas expressive suppression is typically associated with worse emotional outcomes and increased physiological arousal among cancer survivors.22

Successful emotion regulation involves not only counteracting negative emotional experiences but also gaining control over both positive and negative emotions, thus increasing confidence in handling stressors and improving self-efficacy beliefs. However, only a handful of studies have assessed the relationship between emotion regulation and self-efficacy in the context of coping with health conditions,23 and none has involved cancer survivors. A study among individuals with chronic diseases reported improved self-care management subsequent to improved emotion regulation.23

Learning about self-efficacy for coping with cancer and related factors among cancer survivors with preexisting SMHC may provide valuable information to inform interventions that promote quality of life. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to: (a) identify perceptions of self-efficacy for coping with cancer among cancer survivors with precancer SMHC compared to cancer survivors with no prior SMHC; (b) examine the relationships of perceived quality of communication with the oncology team with depressive symptoms and perceived self-efficacy for coping with cancer; and (c) identify patterns of self-regulation (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) in the two groups and their mediating role in the associations of quality of communication with the oncology team with depressive symptoms and cancer self-efficacy.

Materials and methodsParticipants and procedureThe ethics committee of the Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa (No. 320/22) approved this study. Participants were cancer survivors with precancer diagnoses of SMHC. In addition, 80 cancer survivors without SMHC, matched for age and sex, participated as a control group. The inclusion criteria were age 18 or older, 1–5 years since cancer diagnosis, and currently not undergoing active cancer treatment. Those lacking proficiency in Hebrew were excluded. A pretest was conducted to examine the study measures for clarity and initial reliability.

Participants were recruited through a survey institute whose database includes 51,000 individuals diagnosed with cancer and 12,000 individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. These diagnoses were corroborated using official medical documentation provided by the participants. Among them, 3600 individuals met the criteria for both cancer and a psychiatric diagnosis, of them 815 individuals met the inclusion criteria. These individuals were invited to participate in the study. Those who responded were contacted by phone and received a detailed explanation of the study. During the call, their psychiatric diagnosis was verified, and they were asked to sign an informed consent form. The psychiatric diagnoses included schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. Of these individuals, 160 with a dual diagnosis were successfully recruited and interviewed. An additional 10 participants were recruited using a snowball sampling method among those already participating. Participants responded to the questionnaires in a face-to-face meeting with a research assistant.

For the control group, an invitation to participate was sent to 800 cancer survivors who met the inclusion criteria and were randomly selected from the database. Those who responded were contacted by phone and provided with a detailed explanation of the study. Once 80 participants completed the questionnaires, recruitment was concluded.

Sample size was determined using power calculations.24 To detect differences between groups, a minimum of 64 participants per group is needed; for regression analysis involving eight variables (including three or four confounding variables to be controlled), a minimum of 107 participants is needed; and for path analysis employing structural equation modeling, the recommended sample size is 200.25 Missing data was minimal and included one response missing for two variables and nine responses missing for the income item. All missing variables were replaced by the sample mean.

MeasuresSociodemographic details were age, gender, years of education, and income (very low, low, average, or high compared to the monthly average salary in Israel). SMHC-related details were type of diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and use of psychiatric medications. Cancer-related details were type of cancer, time since diagnosis, disease recurrence, and type of cancer therapy.

Cancer-related physical symptoms were examined with four of five items from the EuroQoL Group’s 5-dimension (EQ-5D) measure26—namely, mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, and discomfort. The item probing anxiety and depressive symptoms was not included due to overlap with other items. Item scores ranged from 1 (no problem) to 3 (extreme problem). The measure was validated in previous studies with cancer survivors,27 and the Hebrew version has shown good validity and reliability.28 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the present study was 0.58 in the SMHC group and 0.61 in the control group. Because the tool assesses a range of symptoms, some experienced by some individuals and not others, the total reflects a sum of symptoms rather than a cohesive construct. Thus, high internal consistency is not expected.

Perceived quality of communication with the oncology team was examined with CollaboRATE,29 a 3-item questionnaire measuring the quality of physician communication and shared decision making, including providing information about health issues and integrating patient preferences in clinical decisions. Item scores ranged from 0 (no effort was made) to 4 (every effort was made). A mean score was calculated. Good validity indicators and interrater variability were previously reported.29 The scale was translated into Hebrew using the back-translation method. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the present study was 0.90 in the SMHC group and 0.84 in the control group.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)30 was used to assess depressive symptoms. Item scores ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day); overall scores ranged from 0 to 27. The total score serves as a marker of severity and distress: 1–9 = minimal, 10–14 = mild, 15–19 = moderate, and 20–27 = severe depressive symptoms.30 The tool was translated into Hebrew and other languages and linguistically validated by the MAPI research institute.31 This Hebrew version had been widely used with various populations, and the studies demonstrated good internal consistency and good specificity.32 It was recently revalidated with good psychometric properties.33 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the present study was 0.83 in the SMHC group and 0.80 in the control group.

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire21 is a 10-item scale used to assess emotion regulation. Four items evaluate the degree of use of expressive suppression and six items evaluate cognitive reappraisal. Responses were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Mean scores were calculated for each factor, with higher scores indicating higher levels of expressive suppression and reappraisal. Acceptable internal reliability has been reported,21 along with good reliability for the Hebrew version with cancer survivors.34 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the present study for expressive suppression was 0.62 in the SMHC group and 0.76 in the control group; for cognitive reappraisal, it was 0.82 and 0.81, respectively.

To measure self-efficacy for coping with cancer, this study used the Cancer Behavior Inventory-Brief Version,35 a 12-item version of the original 51-item inventory.36 Respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability to perform behaviors during and after cancer treatment (e.g., maintaining independence, performing self-care activities). Item scores ranged from 0 (not at all confident) to 4 (totally confident). A mean score was calculated, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. Reliability and validity were confirmed.35 The scale was translated into Hebrew using the back-translation method and assessed for clarity, cultural adaptation, and internal consistency. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the present study was 0.73 in the SMHC group and 0.83 in the control group.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics were calculated, followed by Pearson correlation and regression analyses. Next, a multigroup path analysis was conducted with AMOS 27. The model was examined for fit: chi-square and normed chi-square tests to assess the model’s overall fit and parsimony (normed chi-square values equal to or <2.0 indicate good fit); comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and normed fit index (NFI), which are incremental fit indexes; and root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its confidence interval (CI), which measures the discrepancy per degree of freedom and indicates the model’s absolute fit. The direct and indirect paths for each group were assessed. Using bias-corrected bootstrap analysis (5000 bootstraps, 95 % CI) in AMOS, the size and significance of the direct, indirect, and total effects of each path were examined. Finally, the size and significance of differences between groups in structural weights were assessed. Because interviews were face-to-face, there were no missing data.

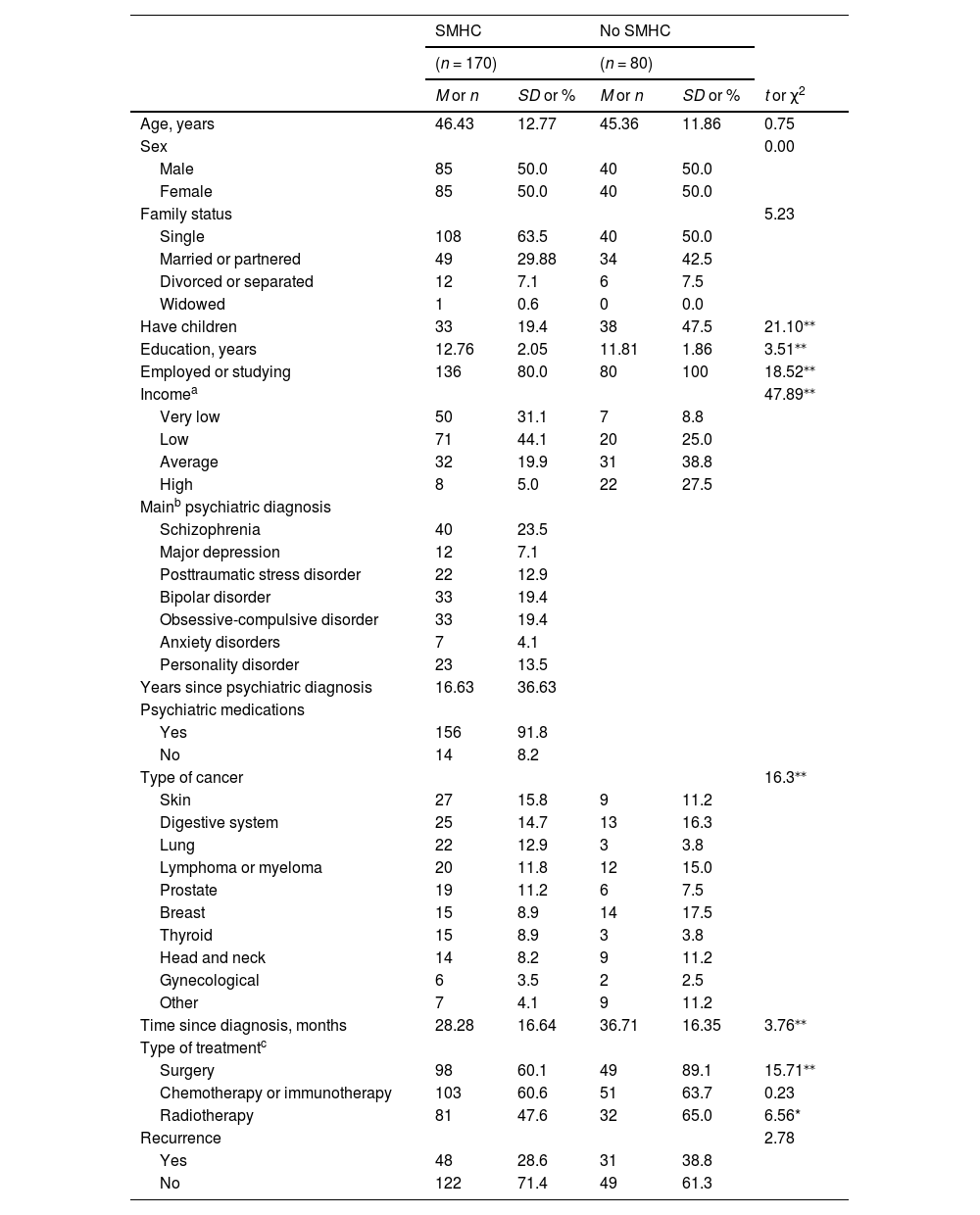

ResultsThe sociodemographic and medical details of the participants are delineated in Table 1. The age range in both groups was 20–71 years, with mean ages comparable between groups. The sampling process was tailored to ensure equal distribution by sex. Although a lower proportion of the SMHC group was married or in a partnership, the difference was not statistically significant. However, a significantly lower proportion of the SMHC group had children, the mean years of education was greater in the SMHC group, and a lower percentage of participants with SMHC were employed. They also reported significantly lower income levels.

Sociodemographic and medical characteristics by group.

| SMHC | No SMHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 170) | (n = 80) | ||||

| M or n | SD or % | M or n | SD or % | t or χ2 | |

| Age, years | 46.43 | 12.77 | 45.36 | 11.86 | 0.75 |

| Sex | 0.00 | ||||

| Male | 85 | 50.0 | 40 | 50.0 | |

| Female | 85 | 50.0 | 40 | 50.0 | |

| Family status | 5.23 | ||||

| Single | 108 | 63.5 | 40 | 50.0 | |

| Married or partnered | 49 | 29.88 | 34 | 42.5 | |

| Divorced or separated | 12 | 7.1 | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Have children | 33 | 19.4 | 38 | 47.5 | 21.10⁎⁎ |

| Education, years | 12.76 | 2.05 | 11.81 | 1.86 | 3.51⁎⁎ |

| Employed or studying | 136 | 80.0 | 80 | 100 | 18.52⁎⁎ |

| Incomea | 47.89⁎⁎ | ||||

| Very low | 50 | 31.1 | 7 | 8.8 | |

| Low | 71 | 44.1 | 20 | 25.0 | |

| Average | 32 | 19.9 | 31 | 38.8 | |

| High | 8 | 5.0 | 22 | 27.5 | |

| Mainb psychiatric diagnosis | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 40 | 23.5 | |||

| Major depression | 12 | 7.1 | |||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 22 | 12.9 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 33 | 19.4 | |||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 33 | 19.4 | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 7 | 4.1 | |||

| Personality disorder | 23 | 13.5 | |||

| Years since psychiatric diagnosis | 16.63 | 36.63 | |||

| Psychiatric medications | |||||

| Yes | 156 | 91.8 | |||

| No | 14 | 8.2 | |||

| Type of cancer | 16.3⁎⁎ | ||||

| Skin | 27 | 15.8 | 9 | 11.2 | |

| Digestive system | 25 | 14.7 | 13 | 16.3 | |

| Lung | 22 | 12.9 | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Lymphoma or myeloma | 20 | 11.8 | 12 | 15.0 | |

| Prostate | 19 | 11.2 | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Breast | 15 | 8.9 | 14 | 17.5 | |

| Thyroid | 15 | 8.9 | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Head and neck | 14 | 8.2 | 9 | 11.2 | |

| Gynecological | 6 | 3.5 | 2 | 2.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 4.1 | 9 | 11.2 | |

| Time since diagnosis, months | 28.28 | 16.64 | 36.71 | 16.35 | 3.76⁎⁎ |

| Type of treatmentc | |||||

| Surgery | 98 | 60.1 | 49 | 89.1 | 15.71⁎⁎ |

| Chemotherapy or immunotherapy | 103 | 60.6 | 51 | 63.7 | 0.23 |

| Radiotherapy | 81 | 47.6 | 32 | 65.0 | 6.56* |

| Recurrence | 2.78 | ||||

| Yes | 48 | 28.6 | 31 | 38.8 | |

| No | 122 | 71.4 | 49 | 61.3 | |

In terms of psychiatric characteristics in the SMHC group, diagnoses were distributed among schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and personality disorders, with a comparatively lower incidence of affective disorders, including anxiety disorders and major depressive symptoms. The duration since diagnosis varied from 4 to 44 months, with an average of 16.63 years; many participants were on regular psychiatric medication.

Regarding cancer-related characteristics, time since diagnosis ranged between 12 and 60 months prior to study participation and was slightly shorter in the SMHC group. Fewer participants in the SMHC group had undergone surgery and radiotherapy. Rates of recurrence were similar between groups. Although significant differences occurred by cancer type, the principal distinction was the higher prevalence of lung cancer and lower prevalence of breast cancer in the SMHC group.

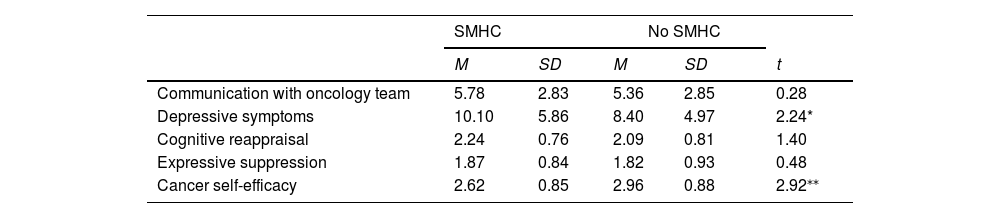

As presented in Table 2, participants in both groups scored the quality of communication with the oncology team as low to moderate on average, with no differences between groups. Depressive symptoms scores were relatively low, albeit higher in the SMHC group. Participants in both groups similarly reported moderate use of cognitive reappraisal and low use of expressive suppression. Cancer self-efficacy scores were moderate, but the mean score was significantly lower among participants with SMHC.

Means and standard deviations of study variables and differences between groups.

Correlations between the study variables in each group are shown in Supplementary Table 1. In the SMHC group only, cancer self-efficacy was significantly associated with perceived communication with the oncology team, whereas in both groups, it was associated with cognitive reappraisal.

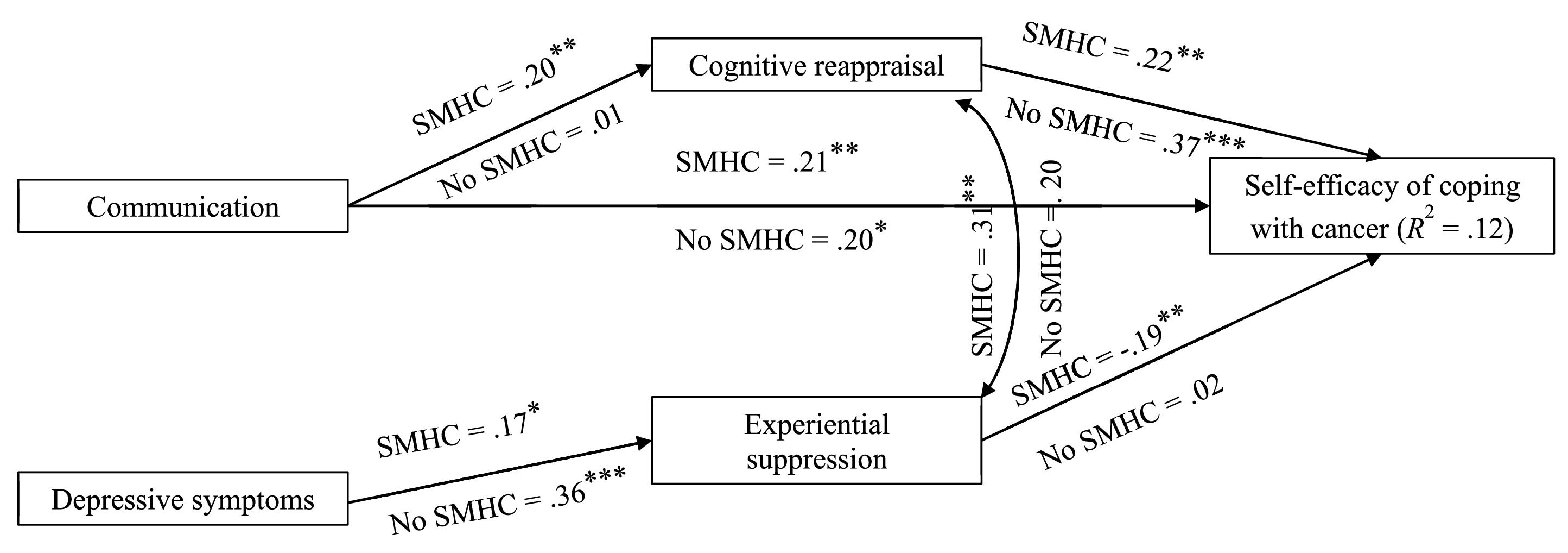

Multigroup path analysisThe path analysis model included perceived quality of communication with the oncology team and depressive symptoms as independent factors, both emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) as mediators, and self-efficacy for coping with cancer as the dependent variable. First, associations between the outcome variable—self-efficacy for coping with cancer—and background variables were tested to identify control variables. Gender, age, time since cancer diagnosis, and physical symptoms were significantly associated with cancer self-efficacy and thus, included in the path analysis model. However, age, time since diagnosis, and physical symptoms were excluded due to lack of associations in the model. The overall model (Fig. 1) had good fit indexes: χ2 = 20.01, df = 14, p = 0.13; χ2/df = 1.45; NFI = 0.82; TLI = 0.84; CFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.04, 95 % CI (0.00, 0.08). The differences between paths in the groups did not reach significance (χ2 = 11.25, p = 0.08).

The size and significance of the direct and indirect associations are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. In both groups, the direct association between communication with the oncology team and cancer self-efficacy was significant and positive. Specifically, the better the communication with the team, the higher the sense of perceived self-efficacy in managing cancer care. Depressive symptoms were not directly associated with self-efficacy. Additionally, in both groups, depressive symptoms were significantly and positively associated with the use of expressive suppression; thus, the higher the depressive symptoms, the more frequent the use of expressive suppression. However, communication with the oncology team was significantly and positively associated with cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression was significantly and negatively associated with self-efficacy only in the SMHC group. Therefore, the higher the cognitive reappraisal and the lower the use of expressive suppression, the higher the perceived self-efficacy.

Direct, indirect, and total bootstrap effects (standardized) by group.

| Pathways | SMHC | No SMHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | |

| Communication → cancer self-efficacy | 21⁎⁎ (0.05, 0.31) | 0.04⁎⁎ (0.01, 0.10) | 0.22⁎⁎ (0.08, 0.36) | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.40) | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.11) | 0.22⁎⁎ (0.08, 0.35) |

| Depressive symptoms → cancer self-efficacy | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | −0.03* (−0.08, −0.01) | −0.04⁎⁎ (−0.07, −0.01) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | −0.00 (−0.06, 0.10) | 0.00 (−0.06, −0.01) |

| Communication → cognitive reappraisal | 0.21* (0.01,0.28) | 0.01 (−27, 0.28) | ||||

| Depressive symptoms → expressive suppression | 0.17⁎⁎ (0.20, 0.42) | 0.36⁎⁎ (0.15, 0.54) | ||||

| Cognitive reappraisal → cancer self-efficacy | 0.26⁎⁎⁎ (0.15, 0.38) | 0.37⁎⁎⁎ (−0.20, 0.22) | ||||

| Expressive suppression → cancer self-efficacy | −0.19* (−0.27, −0.03) | −0.15* (−0.27, −0.03) | 0.02 (−0.21, 0.24) | −0.16* (−0.28, −0.04) | ||

Note. Communication = percieved quality of communication with oncology team.

Bias-corrected bootstrap analysis with 5000 rotations indicated that two mediations were significant in the SMHC group, indicating the role of emotion regulation as a mediator in that group. Specifically, cognitive reappraisal significantly mediated the association between perceived communication with the oncology team and self-efficacy for coping with cancer. The higher the quality of perceived communication, the higher the cognitive reappraisal and perceived self-efficacy. Also, expressive suppression significantly mediated the association between depressive symptoms and cancer efficacy: more severe depressive symptoms were associated with more use of expressive suppression and negatively associated with perceived cancer self-efficacy. The bias-corrected bootstrap analysis indicated that indirect associations in the control group were not significant (Table 3).

DiscussionThe current finding that individuals with SMHC reported diminished self-efficacy for coping compared to cancer survivors with no prior SMHC is of considerable significance, especially due to the previously reported link between low cancer self-efficacy and functioning and quality of life.12 Self-efficacy for coping with cancer had not been previously studied among individuals with SMHC. However, among those with both SMHC and type 2 diabetes, self-efficacy for diabetes management was substantially lower compared to individuals with diabetes alone and associated with poorer self-care behaviors.14 Our results are in line with the cognitive theory of self-efficacy13 and highlight the importance of strengthening self-efficacy among individuals with SMHC, cancer, and chronic illnesses.

The lower self-efficacy for coping with cancer observed among individuals with SMHC may be attributed to a multitude of factors, including their mental health symptoms, limited financial resources, reduced familial support, and smaller social networks.7,9,10 The current study focused on two factors, based on the cognitive theory of self-efficacy,13 that may exert a direct or indirect influence on self-efficacy for coping with cancer: environmental factors (i.e., perceived communication with the oncology team) and personal factors (i.e., depressive symptoms).

The findings indicating that self-efficacy was directly and positively related to the quality of communication in both groups are supported by prior research underscoring the pivotal role of effective communication with multidisciplinary oncology teams in facilitating patient support, alleviating anxiety, and enhancing patient well-being.37 Furthermore, advancements in personalized medicine and the emergence of novel biological and immunotherapeutic interventions necessitate particular attention to the provision of complex information in a manner tailored to the individual’s information processing ability.38 Although participants from both cohorts perceived the quality of communication as low to moderate, given the heightened sensitivity of individuals with SMHC to stigmatizing attitudes from healthcare providers, they might interpret inadequate communication as indicative of negative biases associated with their mental health diagnoses, which may have a devastating effect.17 No previous studies could be located assessing associations between these two factors in relation to cancer or other chronic diseases.

Although studies previously reported that depressive symptoms are associated with lower cancer self-efficacy12 and self-efficacy for coping with chronic illnesses,39 the path analysis model revealed no direct associations. Our current results here are counterintuitive and may suggest that the emotional load is not central. Instead, the emotional regulation process that mediates the association in the SMHC group might be a central mechanism that enhances feelings of confidence and capability, factors central to recovery. However, measurement issues (such as difference between face to face responding and versus online assessments), variability in time since diagnosis or cultural contexts may have affected the present results.40

The association between quality of communication and reappraisal in the SMHC group indicates the significant impact of perceived positive communication on the capacity to engage and implement effective emotion regulation strategies, especially among cancer survivors with SMHC. This role of communication may be intensified by diminished personal and interpersonal resources, restricted social networks, and frequently inadequate familial support.7,9,10,17 Thus, individuals with SMHC could be more vulnerable to the negative attitudes exhibited by professionals15 and might be aided by additional support and reassurance. However, perceived quality of communication was not associated with expressive suppression, potentially indicating that positive communication may foster effective strategies but fail to mitigate ineffective emotion regulation strategies. Conversely, depressive symptoms, typically manifesting as a lack of energy and motivation, may exacerbate the generally ineffective strategy of expressive suppression. This relationship reached statistical significance in both groups, emphasizing the negative and substantial influence of depressive symptoms. Also, no previous studies on cancer or chronic illnesses have explored these associations among individuals with SMHC.

Coping theories emphasize the critical mediating role of emotion regulation strategies, particularly in the interplay between environmental and personal resources and emotional and behavioral outcomes,41 such as self-efficacy. However, in our study, the mediation effect was evident only in the SMHC group. It may be that the resources often unavailable for coping in this population (such as family and friend support) can be compensated by good communication with the oncology team or alternatively, affected by high depressive symptoms. Loss of resources theory, as posited by Hobfoll,42 underscores the necessity of possessing various types of resources to counterbalance deficiencies in other resources. With such resource scarcity, the lack of effective communication with the oncology team may exert a disproportionately stronger impact on the use of effective coping strategies and sense of self-efficacy. Thus, the current mediation results highlight the unique mediational processes linking fragile environmental and personal resources and self-efficacy via emotion regulation strategies among people with SMHC. Conversely, self-efficacy among individuals with no SMHC may be a more robust construct primarily grounded in personal resilience and familial support, with less influence from particular emotion regulation strategies.

ImplicationsThe results have several implications for both practice and health policy. Primarily, the results corroborate prior recommendations advocating enhanced attention and time to the dissemination and discussion of information pertinent to cancer patients with SMHC.43 Furthermore, they illuminate the fragility of self-efficacy in coping with cancer among individuals with SMHC, emphasizing the imperative to foster this self-efficacy to promote improved quality of life. This may be achieved by training healthcare providers to use the teach-back method during patient interactions.44 This structured communication technique helps ensure that patients understand the information being shared while acknowledging their emotional responses. Research has shown that the teach-back method improves treatment adherence and self-care.44

The results thereby also advocate the enhancement of psycho-oncology screening for distress and the provision of intensive psycho-oncology support, necessitating an increase in psycho-oncology personnel and the delivery of specialized education focused on care for individuals with both SMHC and cancer. Another implication pertains to the major role of emotion regulation strategies in self-efficacy. Psycho-oncology professionals should consider incorporating two-pronged interventions for cancer survivors with SMHC that address expressive suppression, build more adaptive emotion regulation skills strategies, and enhance well-being using evidence-based interventions such as mindfulness,45 DBT46 or ACT.47

LimitationsThis study has several limitations, particularly regarding the recruitment process, which may have introduced a bias toward individuals with SMHC exhibiting relatively higher levels of functioning and thus, excluding those with more profound mental health challenges and diminished personal functioning. Moreover, the research employed a cross-sectional design rather than collecting longitudinal data. An additional limitation is the low internal consistency of the experiential suppression subscale of the emotion regulation measure, especially in the SMHC group; thus, results should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, this investigation is one of the few studies addressing coping with cancer among individuals with preexisting SMHC. Its strengths include the use of a comparison group, which allowed for the identification of differences and similarities in the examined factors and processes. Research employing longitudinal methodologies is essential to developing a more nuanced understanding of the coping characteristics associated with cancer among individuals with SMHC.

ConclusionsThis study aimed to improve our limited understanding regarding individuals with SMHC who are dealing with cancer, with a focus on their firsthand accounts in contrast to the scant literature consisting primarily of accounts by healthcare practitioners.11 The findings highlight the need for psychosocial interventions that strengthen the sense of self-efficacy among cancer survivors with preexisting SMHC. The results also suggest a focus on strengthening effective emotion regulation strategies to achieve this end. Although direct interventions and provision of ongoing support from psycho-oncologists is important, the results also stress the central role of communication with the oncology team in strengthening both effective emotion regulation and cancer self-efficacy. Thus, oncology professionals should receive tools to communicate effectively with individuals with SMHC to improve their quality of life.

FundingThis work was supported by the Israel Scientific Foundation (no 524/22).

Ethics approvalThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Haifa (No. 320/22). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional or national research committee.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMiri Cohen: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Marc Gelkopf: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.