Depression is a major mental system disorder, and previous studies have found an association between herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection and depression. However, recently researches report that depression can be divided into two categories, cognitive symptoms and somatic symptoms, but the relationship between the subtypes of depression is still unknown.

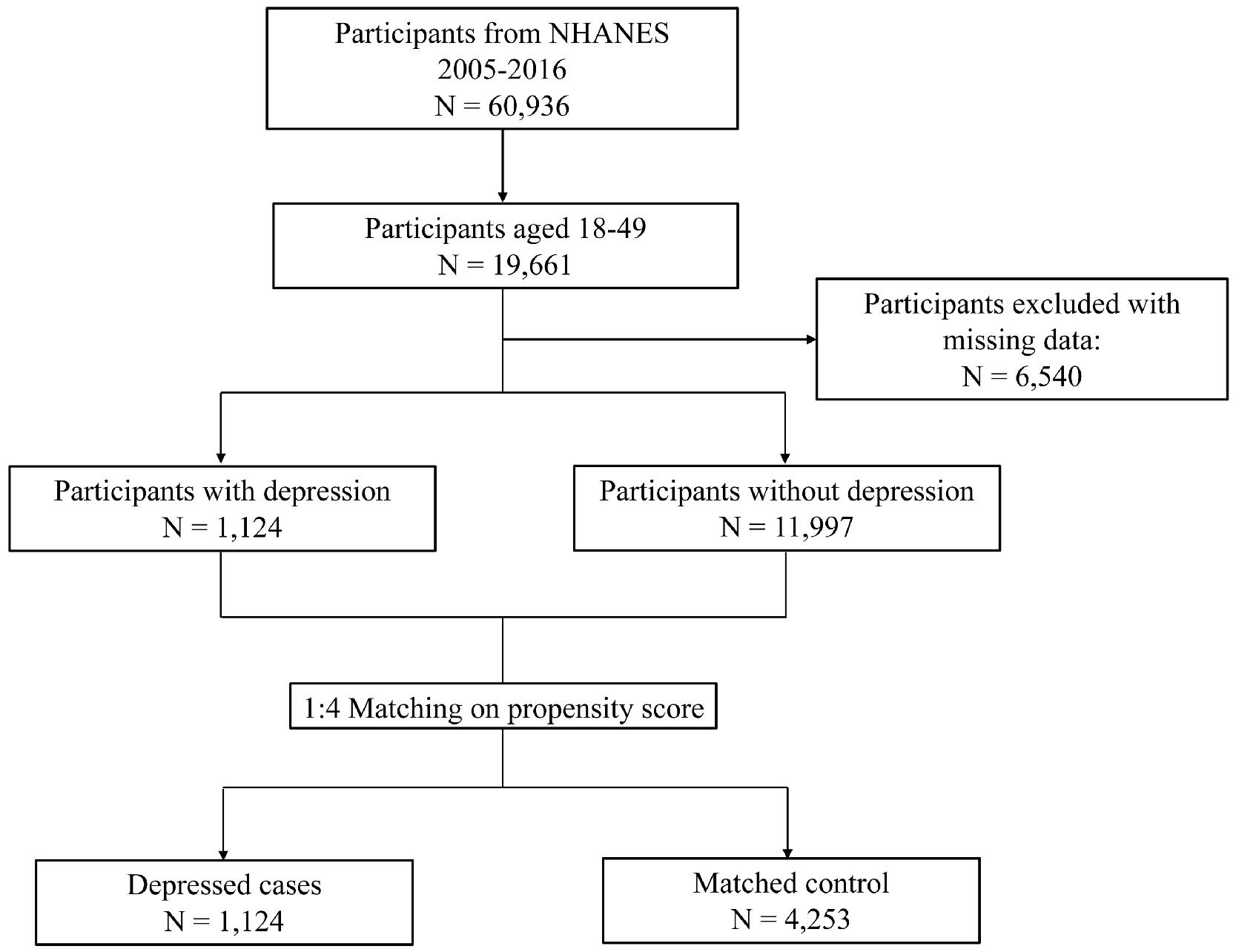

MethodsWe obtained NHANES data from cycles 2005–2016, and a total of 1124 depressed cases and 4253 matched controls were selected achieving a 1:4 matching ratio. Logistic regression was used to explore the association of HSV-2 infection with depression status and severity. Zero-inflated negative binomial regression was employed to assess associations between HSV-2 infection and specific cognitive/somatic symptoms of depression.

ResultsHSV2 infection was positively associated with depression status (OR=1.33, 1.11∼1.59) and severity (OR=1.24, 1.05∼1.45), but these associations were only observed in female, not in male. Furtherly, result of Zero-inflated negative binomial regression suggested that HSV2 infection increased total score of somatic symptoms (RR=1.15, 1.16∼1.25) rather than cognitive symptoms in female. Moreover, HSV2 infection was related to increasing somatic symptoms, including sleeping difficulties, fatigue and appetite problems, but not any cognitive symptoms.

ConclusionHSV-2 infection is positively associated with depression status only in females, but not in males. HSV-2 infection appears to be primarily related to somatic symptoms rather than cognitive symptoms in the female population.

In recent years, the global landscape of depression presents a complex and evolving mental health challenge, affecting approximately 298 million people worldwide, which represents about 4–5 % of the global population.1,2 Year's epidemiological data reveals a nuanced picture of mental health, with significant variations across different regions and demographic groups. Gender disparities persist, with women experiencing a depression rate of 5.1 % compared to 3.6 % for men, underscoring the ongoing need for gender-specific mental health approaches.3 Global statistical data shows that young adults aged 18–25 are identified as the most vulnerable demographic, facing the highest risk of depressive symptoms.4 Numerous interconnected factors drive these trends in depression, including economic uncertainties, the pervasive influence of social media, growing digital isolation, and emerging psychological responses to global challenges such as climate change. These complex social dynamics have created a multifaceted environment that significantly influences mental health outcomes.5 As global challenges become increasingly intricate and interconnected, addressing depression necessitates a multifaceted approach that considers psychological, social, economic, and viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV) .6,7

HSV infection poses significant public health challenges worldwide, affecting millions of individuals and carrying substantial implications for both physical and mental health. HSV is primarily categorized into two types: HSV-1, responsible for oral herpes, and HSV-2, which is most commonly associated with genital herpes. The global prevalence of HSV-1 is estimated to be around 67 % among individuals under 50, indicating its widespread nature, while HSV-2 affects approximately 11 % of the population.8,9 Many individuals infected with HSV remain asymptomatic, meaning they may be unaware of their status, which complicates efforts to control transmission and can lead to potential outbreaks during periods of stress, illness, or other triggers. Recent epidemiological studies observed a correlation between HSV-2 infection, but not HSV-1, and increased rates of depressive symptoms.10 A study published in 2018 reported that HSV-2 seropositivity was associated with higher rates of depressive disorders after controlling for potential confounders such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status.11 This reinforces the notion that HSV-2 may directly or indirectly impact mental health. Moreover, the bidirectional relationship between HSV-2 and depression is significant; individuals with preexisting depressive disorders may also be at increased risk for contracting HSV-2 due to factors such as reduced engagement in safe sexual practices or diminished immune function.12,13 Thus, this cycle of infection and depression emphasizes the importance of considering depression as an integral component of the management strategy for individuals diagnosed with HSV-2.

Depression can be broadly categorized into cognitive and somatic (or physical) symptoms.14 Cognitive symptoms involve alterations in thought processes, affecting how individuals perceive themselves and their environment. Common cognitive symptoms include persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and worthlessness, alongside difficulties in concentration, decision-making, and memory. Individuals may experience an overwhelming sense of failure or pessimism about the future, which can exacerbate their depressive state. These cognitive distortions can manifest as negative self-talk, rumination, and a skewed perception of reality, sometimes leading to suicidal ideation. The cognitive dimension of depression is particularly important, as it influences emotional regulation and can directly impact behavioral responses, contributing to a cycle that perpetuates the disorder.14,15 In contrast, somatic symptoms focus on the physical manifestations of depression, which are often overlooked in clinical settings. These symptoms can range from fatigue, insomnia, and changes in appetite to more specific complaints such as gastrointestinal issues, headaches, and generalized pain. Somatic symptoms may sometimes be mistaken for other medical conditions, leading to potential misdiagnosis or inadequate treatment. The presence of physical symptoms can significantly affect an individual's quality of life, resulting in functional impairment in daily activities and an increased risk of comorbid medical conditions.16

The distinction between cognitive and somatic symptoms has important implications for treatment approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is often effective in addressing the cognitive aspects of depression by helping individuals identify and restructure negative thought patterns.17 In contrast, treatments focusing on somatic symptoms may involve pharmacotherapy, lifestyle changes, and interventions aimed at physical well-being, such as exercise and nutrition.18 Antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), can alleviate both cognitive and somatic symptoms, but their efficacy may vary among individuals based on symptom profiles. For instance, some individuals may present predominantly with somatic symptoms and require a more tailored approach that addresses physical health concerns alongside mental health treatment.19 This highlights the necessity to treat cognitive and somatic symptoms in patients differently, as cognitive and somatic symptoms of depression have different origin, clinical significance and treatment. However, previous studies have primarily focused on the correlation between diagnosed depression and HSV-2 infection without investigating these associations of subtypes and infection. Understanding the distinctions between these two symptoms are crucial for accurate diagnosis, treatment, and management of depression.

Therefore, in the current study, we aim to explore the association between depression and HSV-2 infection, further investigating the correlation of cognitive and somatic (or physical) symptoms with infection to clarify the mechanisms by which HSV-2 infection may contribute to depression.

MethodsStudy design and populationThe study data was derived from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive, nationwide investigation conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NCHS is headquartered in Hyattsville, Maryland, USA, and monitors population health trends in the United States. The NHANES obtained ethical approval from NCHS Ethics Review Board. Written consents were obtained from all participants during enrollment. This study is a secondary analysis of publicly available dataset, hence additional institutional review board approval is not required.

This study obtained NHANES data from cycles 2005–2016. Participants aged between 18 and 49 years were included, as the depression questionnaire was administered exclusively to this population. Participants with missing data on covariates were then excluded. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to match depressed individuals (cases) with non-depressed individuals (controls), balancing characteristics between two groups. Confounding factors including age (±5 years), sex, race, educational level, poverty-income ratio and marriage status were put into logistic regression models to estimate propensity score. A nearest neighbor approach with a caliper value of 0.2 was employed to achieve a 1:4 matching ratio (1 case to 4 controls). Finally, a total of 1124 depressed cases and 4253 matched controls were selected and included in final analyses (Fig. 1).

Data collectionThe participants attended scheduled Mobile Examination Clinic (MEC) for standardized interviews, physical examinations and biospecimen collection during the same visit. NHANES interviews were conducted by trained interviewers, where questionnaires were administered to collect information on demographics, lifestyle factors and medical conditions. Demographic factors include age (continuous), sex (male or female), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black or others), education level (below high school, high school or equivalent, or above high school), PIR (≤1.0, 1.0–3.0 or >3.0) and marriage status (no or yes). Body mass index (BMI) were measured at the MEC and was classified into 3 levels: <25 kg/m2 (normal/underweight), 25–30 kg/m2 (overweight) or ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese). Lifestyle factors was collected by questionnaire. Smoking status was categorized as never (<100 cigarettes in a lifetime), former (≥100 cigarettes in a lifetime but quit smoking at the time of the survey), or current smokers (≥100 cigarettes in a lifetime and still smoked at the time of the survey). Drinking status was categorized as never (<12 drinks in a lifetime), former (had drunk ≥12 drinks in a lifetime but none in the past year), or current drinkers (≥12 drinks in a lifetime and at least one in the past year). For comorbidities, the criteria for hypertension diagnosis included: 1) self-reported physician diagnosis, or 2) current use of prescribed antihypertensive medications, or 3) physical examination measurements demonstrating elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥90 mmHg). The criteria for diabetes diagnosis include: 1) self-reported physician diagnosis, or 2) current use of prescribed glucose-lowering medications, or 3) biochemical confirmation of fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or glycohemoglobin ≥6.5 %.

Blood specimens were obtained from MEC. Type-specific glycoprotein gG-2 was utilized as antigens in the serological assays to identify HSV-2 antibody seropositivity. The glycoprotein was purified using monoclonal antibodies and affinity chromatography, and then was detected by solid-phase enzymatic immunodot assays. The HSV-2 seropositivity status was reported as binary variable (positive and negative).

Assessment of depressionDuring the MEC visit, participants underwent interviews of depression screening tools, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) by trained interviewers. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item instrument evaluating severity of depressive symptoms. Participants aged 18 to 49 years were interviewed by trained interviewers. Each item in the PHQ-9 was rated on a 4-point scale, with response options scoring from 0 to 3: "not at all," "several days," "more than half the days" and "nearly every day". The total PHQ-9 score was derived by summing the individual item scores, ranging from 0 to 27. The definition of depression was determined at a cut-point of 10, with scoring≥10 defined as depressed individual. Depression severity was further categorized into 4 levels: no depression (<10), moderate depression (10–14), moderately severe depression (15–19) and severe depression (20–27) .20 According to previous studies, two dimensions of depressive symptoms were identified within the PHQ-9: cognitive and somatic dimensions.21–23 The cognitive dimension included 5 items: lack of interest, depressed mood, low self-esteem, concentration difficulties and suicidality. The somatic dimension comprises the remaining 4 items: sleeping difficulties, fatigue, appetite problems and psychomotor. For both dimensions, scores were calculated by summing the corresponding item scores to discriminate the specific areas of depressive symptom associated to HSV-2 infection.

Statistical analysisWeighted multivariate logistic regression and ordinal logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations of HSV-2 infection with depressive status and depression severity. The sex difference in association between HSV 2 infection and depression was examined. Hence subgroups of male and female was constructed according to this binary classification. For depressive symptom scores, which exhibited a high proportion of zero values, zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were fitted. The zero-inflated negative binomial regression model consists of two components: the zero-inflated logistic part assessing likelihood of observing non-zero values; and the negative binomial part assessing the severity of depressive symptoms as indicated by the increments in scores.23 The negative binomial portion was clinically interpretable as depressive symptom severity,24 reported by rate ratio (RR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI). Full model adjustments included covariates: age, sex, race, education level, PIR, marriage status, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, history of hypertension and diabetes. Statistical significance is defined at P < 0.05. All data analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationIn the current study, we conducted a case-control analysis with a 1:4 matching ratio based on the criteria outlined in the methods section. No significant differences were observed between the case and control groups regarding age, sex, race, education level, poverty-income ratio, or marital status. However, there were notable differences in body mass index (BMI) and HSV-2 antibody seropositivity between the groups. Specifically, the BMI of the case group was lower than that of the control group, and the positive rate of HSV-2 antibody seropositivity, indicating HSV-2 infection, was higher in the case group (32.47 %) compared to the control group (26.45 %) (Table 1). This finding suggests that the infection rate of HSV-2 is higher in the population with depression.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Depressed cases(N = 1124) | Matched controls(N = 4253) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 35.28 (8.69) | 34.84 (8.69) | 0.127a |

| Sex | 0.219b | ||

| Male | 368 (32.74) | 1478 (34.75) | |

| Female | 756 (67.26) | 2775 (65.25) | |

| Race | 0.226b | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 487 (43.33) | 1735 (40.79) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 262 (23.31) | 992 (23.32) | |

| Others | 375 (33.36) | 1526 (35.88) | |

| Education level | 0.396b | ||

| Below high school | 348 (30.96) | 1231 (28.94) | |

| High school or equivalent | 278 (24.73) | 1102 (25.91) | |

| Above high school | 498 (44.31) | 1920 (45.14) | |

| Poverty-income ratio | 0.112b | ||

| ≤1.0 | 466 (41.46) | 1618 (38.04) | |

| 1.0–3.0 | 465 (41.37) | 1866 (43.87) | |

| >3.0 | 193 (17.17) | 769 (18.08) | |

| Marriage status | 0.796b | ||

| No | 765 (68.06) | 2875 (67.60) | |

| Yes | 359 (31.94) | 1378 (32.40) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001b | ||

| <25 | 316 (28.11) | 1365 (32.09) | |

| 25–30 | 284 (25.27) | 1268 (29.81) | |

| ≥ 30 | 524 (46.62) | 1620 (38.09) | |

| HSV-2 antibody seropositivity | <0.001b | ||

| No | 759 (67.53) | 3128 (73.55) | |

| Yes | 365 (32.47) | 1125 (26.45) |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; HSV-2: herpes simplex virus type 2; SD: standard deviation.

We employed logistic regression models to investigate the association between HSV-2 infection and depression. Our analysis revealed that HSV-2 infection was associated with an increased rate of depression in the overall population (OR=1.33, 95 % CI: 1.11–1.59). However, this association was significant only in females (OR=1.46, 95 % CI: 1.16–1.84) and not in males (Table 2). We incorporated the interaction term of sex and HSV-2, and found it marginally significant (P for interaction=0.051). Furthermore, we categorized depression status into four levels based on the PHQ-9 score to examine the relationship between HSV-2 infection and depression severity. Consistent with our previous analysis, ordinal logistic regression models indicated that HSV-2 infection was positively associated with depression severity in the overall population (OR=1.24, 95 % CI: 1.05–1.45). This association was again observed only in females (OR=1.28, 95 % CI: 1.06–1.54) and not in the male population (Table 2).

Association between HSV-2 infection and depression status and severity.

| Depressed statusa | Depression severityb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | P | OR (95 % CI) | P | |

| All | 1.33 (1.11, 1.59) | 0.003 | 1.24 (1.05, 1.45) | 0.009 |

| Male | 0.99 (0.67, 1.46) | 0.954 | 1.10 (0.81, 1.49) | 0.539 |

| Female | 1.46 (1.16, 1.84) | 0.002 | 1.28 (1.06, 1.54) | 0.011 |

Models were adjusted for age, race, education level, poverty-income ratio, marriage status, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, history of hypertension and diabetes. Abbreviations: CI: confidence intervals; OR: odds ratio.

Considerable heterogeneity has been observed in the expression of symptoms among individuals diagnosed with depression.25 These symptoms can be categorized into two types: somatic symptoms (negative mood or affect) and cognitive symptoms (fatigue, bodily discomfort). We aimed to explore the relationship between HSV-2 infection and these two symptom types. A zero-inflated negative binomial regression, which is suitable for analyzing this type of scoring data, was employed to assess these associations. Our findings indicated that HSV-2 infection was associated with somatic scores (RR=1.14, 95 % CI: 1.06–1.22), but not with cognitive scores (RR=1.08, 95 % CI: 0.99–1.18) across the entire population. However, these associations were not present in males. In females, the RRs were 1.10 (95 % CI: 0.99–1.22) for total cognitive scores and 1.15 (95 % CI: 1.06–1.25) for somatic scores, respectively (Table 3).

Zero-inflated negative binomial regression assessing association of HSV-2 infection with depressive symptom dimension score.

| Cognitive scorea | Somatic scorea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95 % CI) | P | RR (95 % CI) | P | |

| All | 1.08 (0.99, 1.18) | 0.100 | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.01 (0.85, 1.21) | 0.895 | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) | 0.243 |

| Female | 1.10 (0.99, 1.22) | 0.080 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.25) | 0.001 |

Models were adjusted for age, race, education level, poverty-income ratio, marriage status, body mass index, smoking status, drinking status, history of hypertension and diabetes.

Abbreviations: CI: confidence intervals; RR: rate ratio.

In Fig. 2, we further analyzed specific indicators of cognitive and somatic symptoms. Surprisingly, HSV-2 infection did not appear to affect cognitive symptoms, including lack of interest, depressed mood, low self-esteem, concentration difficulties, and suicidality, as no statistical differences were observed in either the male or female groups. In contrast, in the somatic dimension, HSV-2 infection was associated with symptoms in females, including sleep difficulties (RR=1.22, 95 % CI: 1.09–1.36), fatigue (RR=1.15, 95 % CI: 1.06–1.24), and appetite problems (RR=1.16, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.32). The association between HSV-2 infection and psychomotor symptoms was borderline insignificant (p = 0.055). Interestingly, fatigue (RR=1.34, 95 % CI: 1.03–1.76) was associated with HSV-2 infection in males, which is inconsistent with the results for the total somatic score in males. Collectively, these results suggest that HSV-2 infection may primarily exacerbate the somatic symptoms of depression rather than cognitive symptoms in the female population.

Associations of HSV-2 infection with depressive symptom severity among males (A) and females (B) estimated by the zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. The filled circles represent rate ratios, and the horizontal lines represent 95 % confidence intervals. Zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were adjusted for age, race, education level, poverty-income ratio, marriage status and body mass index. Abbreviations: CI: confidence intervals; RR: rate ratio.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between HSV-2 infection and depression and found that HSV-2 infection was positively associated with both depression status and severity, but this association was only observed in females, not in males. Furthermore, HSV-2 infection appeared to associate with the somatic symptoms of depression rather than cognitive symptoms in the female population.

HSV-2 infection has been identified as a significant risk factor for mental illnesses, including depression. Gale et al. (2018) found that HSV-2 was associated with an increased risk of depression in a sample of adults in the United States, whereas HSV-1, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B were not associated.11 Due to the high prevalence of HSV-2, its infection has garnered increasing attention in recent years, revealing crucial insights into how HSV-2 viral infections influence mental health.26 One key factor is that HSV-2 can cause genital herpes, and the stress and stigma associated with an HSV-2 diagnosis can exacerbate feelings of shame, anxiety, and isolation, contributing to the development of depressive symptoms.27 Individuals living with HSV-2 often face social stigma, leading to compromised relationships and reduced social support—both of which are significant risk factors for depression.28 Moreover, the biological effects of HSV-2 on the central nervous system may also play a role. Research indicates that HSV-2 can elicit neuroinflammatory responses that disrupt normal brain function.29,30 This neuroinflammation is thought to contribute to the dysregulation of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, which are critical for mood regulation.31 Chronic activation of the immune system can lead to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which have been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.32 Thus, the immune response triggered by HSV-2 may not only result in physical symptoms but also contribute to psychological distress. Additionally, the reactivation of HSV-2 from a dormant state is often triggered by physiological and psychological stressors, further exacerbating both immune dysregulation and mental health concerns in affected individuals.33 Collectively, these factors may jointly contribute to depression. Actually, depression could also potentially contribute to an increased risk of HSV-2 infection. Depression is often associated with impulsive behaviors, poor decision-making, and social withdrawal. Individuals with depression may be more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex or having multiple sexual partners, which increases the likelihood of acquiring HSV-2.34 Additionally, depression has also been linked to dysregulation of the immune system, and chronic stress and depression can suppress cellular immunity, including natural killer cell activity and T-cell function, which are critical for defending against viral infections like HSV-2.35 Thus, this bidirectional association of depression and HSV-2 infection make it difficult to conclude the causal relationship in our study.

Our sex-stratified analysis revealed interesting sex differences. Female populations consistently showed higher correlation rates between HSV-2 infection and depression, whereas no such association was observed in males. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in 2023, which indicated that females (OR: 1.43, 95 % CI: 1.03–1.97, P = 0.032) with HSV-2 infection had greater odds of experiencing depressive symptoms compared to males (OR: 1.20, 95 % CI: 0.69–2.08, p = 0.509) .12 The observed sex difference may relate to hormonal influences, immunological variations, and potential comorbidities. Women's immune responses differ from those of men, females generally exhibit stronger immune responses, which can be protective but may also lead to their increased susceptibility to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Therefore, females with HSV-2 might experience more pronounced chronic inflammatory and have higher levels of cytokines associated with stress and inflammation after HSV infection, potentially increasing the risk of developing depression.36,37 This may due to the different effects of sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone, which play a significant role in modulating immune responses. Estrogen is known to enhance both innate and adaptive immune responses via activating ER signaling in immune cells, which enable protein–protein interactions between ERs and ERE-independent transcription factors, including NF-κB, specific protein 1 (SP1) and activator protein 1 (AP-1), resulting in enhanced production of IFNγ and overall cytotoxicity.38 Conversely, higher levels of testosterone could reduce the synthesis of TNF, iNOS and NO and increase IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) synthesis, causing increased anti-inflammatory responses via androgen receptor signaling.39 Hormonal fluctuations, especially during menstruation and menopause, can influence mood and immune function.40 Additionally, women may face more significant stigma associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), leading to feelings of shame, anxiety, and low self-esteem.41 This stigma may be compounded by societal expectations regarding women's sexual health and behavior.42 When considering coping strategies and social support systems for managing STIs, women may often find themselves lacking necessary resources, resulting in higher rates of depression. Another important factor is the impact of comorbidities. Anxiety disorders and other STIs, which commonly occur alongside HSV, may present higher predisposing factors in women.43 The interplay between these conditions can confound the relationship between HSV and depression, making it challenging to determine causation versus correlation. Our results indicate that HSV-2 infection is associated with depression in females.

The clinical features of depression can be divided into cognitive and somatic symptoms. Individuals with pronounced somatic symptoms of depression demonstrate reduced awareness of behavioral errors.14 Another study observed that somatic symptoms, rather than cognitive symptoms, are associated with mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction or chronic heart failure.44,45 Our results also found an association between somatic depression symptoms and HSV-2 infection in females. Somatic symptoms of depression, which manifest as physical ailments or discomfort, can profoundly impact an individual's overall health and potentially contribute to the promotion of various diseases.46 Chronic depression and its somatic manifestations can lead to prolonged activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in sustained secretion of cortisol, the body's primary stress hormone.47 Elevated cortisol levels can have multiple adverse effects on the body, including immune system suppression, increased inflammation, and higher risks of metabolic syndrome.48 Persistent inflammation has been linked to various chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders. Moreover, individuals with somatic depression often report sleep disturbances, which can further exacerbate the risk of chronic health problems. Poor sleep quality and sleep disorders, such as insomnia or hypersomnia, not only intensify depressive symptoms but are also significant risk factors for obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.49 Early intervention and integrative care models that combine medical and psychological therapies are vital in preventing the progression from depression to disabling chronic illnesses.

While somatic symptoms received significant attention, we cannot conclude that they are more crucial than cognitive symptoms in depression. Two studies demonstrated that cognitive symptoms, but not somatic symptoms, were associated with mortality in hemodialysis patients.50,51 It is essential to recognize that these two symptom types are interrelated, despite their distinct nature. The presence of somatic symptoms can lead to increased cognitive distress, while cognitive distortions may exacerbate physical discomfort. Our results emphasized the need for individuals with HSV-2 infection to pay closer attention to somatic depression symptoms, which may contribute to increased mortality and the development of diseases.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causality between HSV-2 infection and depression. Secondly, the assessment of depression in this study relied on self-reported depressive symptoms in PHQ-9 instrument. While the PHQ-9 demonstrated a validated screening tool for depression, it may still introduce recall bias and lead to underestimation of depression prevalence. Future studies should incorporate clinician-administered scales, for example the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, to improve diagnostic precision. Another limitation is that the binary classification of biological sex in NHANES prevents exploration of gender-diverse populations. Future studies should collect gender identity data to better understand how social constructs of gender and biological sex interact in health outcomes among HSV-2 patients. Additionally, while our categorization of somatic symptoms and cognitive symptoms provided a useful framework for analysis, it should be interpreted with caution due to the arbitrary nature of the division. further researches are needed for better understanding the interplay between somatic and cognitive symptoms of depression and developing more refined tools for symptom assessment. Moreover, while the current analysis adjusted for major confounders including socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors and comorbidities, residual confounding from unmeasured variables may still exist. For example, other laboratory-confirmed STI status, indicators for childhood trauma/adversity or hormonal contraceptive data were unavailable in NHANES 2005–2016 cycles. Future studies incorporating these data would enhance precision in estimating associations between HSV-2 and depression. The NHANES data is representative of the US population, its generalizability to other populations may be limited due to differences in HSV-2 prevalence, cultural factors, and healthcare access. Our findings should be validated in diverse populations to better understand the relationship of HSV2 and depression. Finally, while we found an association between HSV-2 infection and depression in females but not in males, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Investigating sex hormones and their influences on this relationship could be beneficial.

ConclusionIn the present study, we explored the relationship between HSV-2 infection and depression using data from the NHANES. Our findings indicate that HSV-2 infection is positively associated with depression status only in females, but not in males. Additionally, HSV-2 infection appears to be primarily related to somatic symptoms rather than cognitive symptoms in the female population. These results provide valuable insights into identifying the relationship between HSV-2 infection in females and depression, especially concerning somatic symptoms, which may contribute to increased mortality and disease risk.

Ethical considerationsThe study data was derived from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive, nationwide investigation conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A wide range of investigations including in-home interview, physical measurement and laboratory tests were conducted on study population. Written consents were obtained from all participants during enrollment.

FundingThis work is supported by Clinical Research Special Project for Health Industry of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20224Y0335); Pudong New Area Science and Technology Development Innovation Fund (PKJ2022-Y94); Shanghai Traditional Chinese Medicine Characteristic Disease Specialty (Community) Capacity Building (SOZBZK-23–34); Pudong New Area Science and Technology Development Innovation Fund (PKJ2023-Y71).

The authors declare no competing interests.

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx).