To determine the relationship between enteral nutrition discontinuation and outcome in general critically ill patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:All patients admitted to a mixed intensive care unit in a tertiary care hospital from May-August 2009 were screened for an indication for enteral nutrition. Patients were followed up until leaving the intensive care unit or a maximum of 28 days. The gastrointestinal failure score was calculated daily by adding values of 0 if the enteral nutrition received was identical to the nutrition prescribed, 1 if the enteral nutrition received was at least 75% of that prescribed, 2 if the enteral nutrition received was between 50-75% of that prescribed, 3 if the enteral nutrition received was between 50-25% of that prescribed, and 4 if the enteral nutrition received was less than 25% of that prescribed.

RESULTS:The mean, worst, and categorical gastrointestinal failure scores were associated with lower survival in these patients. Age, categorical gastrointestinal failure score, type of admission, need for mechanical ventilation, sequential organ failure assessment, and Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores were selected for analysis with binary regression. In both models, the categorical gastrointestinal failure score was related to mortality.

CONCLUSION:The determination of the difference between prescribed and received enteral nutrition seemed to be a useful prognostic marker and is feasible to be incorporated into a gastrointestinal failure score.

Intensive care unit (ICU) patients suffering from under-nutrition have a poor outcome (1,2). The consequences of malnutrition are considerable and include an increase in the length of mechanical ventilation, septic complications, length of ICU stay and health care costs (3-6).

Gastrointestinal problems occur regularly in critically ill patients and are related to worse outcomes (7). However, there is no consensus method for obtaining an accurate assessment of gastrointestinal function (7). In general, enteral nutrition (EN) is the recommended method of artificial feeding in intensive care units, but a major concern with EN is the discrepancy between the prescribed and delivered amounts of nutrients (8-10). EN reverses the loss of gastrointestinal mucosal integrity (11,12), maintains intestinal blood flow (13), and preserves IgA-dependent immunity (14-16). In addition, survival during intensive care is improved with the earlier introduction of EN (17), but generally, the relationship between the prescribed and delivered amounts of nutrients is not used as a sign of gastrointestinal dysfunction. A gastrointestinal failure (GIF) score based on food intolerance and intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) predicts mortality in critically ill patients (18), but because intra-abdominal pressure monitoring is not routinely used in ICUs (19), we hypothesized that it would be possible to predict mortality in critically ill patients by using a marker of food intolerance.

Thus, the present study determined the relationship between EN discontinuation and outcome in general critically ill patients to use this information to determine a gastrointestinal failure (GIF) score in critically ill patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThe Ethics Committee of the Universidade do Extremo Sul Catarinense approved the study. Because EN is the standard feeding route in the ICU, informed consent was waived.

All patients admitted to a mixed ICU in a tertiary care hospital from May-August 2009 were prospectively screened for study inclusion. All patients older than 18 years with an indication for EN were included. EN was considered in patients unable to resume oral feeding within 4–5 days. Early EN (<48 h after ICU admission) was started according to the patient’s clinical condition. The ICU protocol defined a stepwise daily increase in nutrient delivery with the aim of providing the maximum feeding volume between four and seven days, with a caloric goal of 20-25 kcal/kg/day. Both gastric and postpyloric feeding could be used.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected. The Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was estimated using data collected at ICU admission (±1 h) and during the first 24 h of ICU stay. The sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score was calculated on the first day of ICU admission. Patients were followed up until discharge from the ICU or a maximum of 28 days.

Because short periods of feeding could not precisely demonstrate the problems associated with EN, only patients with a minimum feeding period of five days were included in this analysis. The GIF score was calculated from day three until EN was discontinued because EN was prescribed to the vast majority of patients between 36-48 h after ICU admission. The GIF score was calculated daily by adding values of 0 if the EN received was identical to the EN prescribed, 1 if the EN received was at least 75% of prescribed, 2 if the EN received was 50-75% of prescribed, 3 if the EN received was 50-25% of prescribed, and 4 if the EN received was less than 25% of prescribed. From these values, the mean GIF score (obtained by the sum of each GIF score divided by the amount of days that EN was given), the worst GIF score (defined as the lowest score during the time that EN was given), and the categorical GIF score (separately grouping patients with the worst GIF score of 0 or 1 and patients with GIF score > = 2) were calculated.

Clinical data were analyzed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 15.0). Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population. Continuous variables were reported as the mean±standard deviation or the median (25-75% interquartile range), depending on the variable distribution, as determined by analysis with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To identify factors associated with outcomes, a univariate analysis was performed on all collected variables using a chi-squared test for categorical variables or Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate, for continuous variables. Variables yielding p<0.25 in the univariate analysis or considered clinically relevant were entered into a binary logistic regression model. Thus, age, categorical GIF score, type of admission, and the need for mechanical ventilation were selected for a binary regression analysis. Two models were fitted considering either the SOFA score or the APACHE II score. The need for vasopressors was not included in the models concerning colinearity with SOFA and APACHE II scores. The relationship between mortality and gastrointestinal function was also analyzed by Kaplan-Meier curves followed by the log-rank test. A two-tailed test was used to determine statistical significance (p<0.05).

RESULTSA total of 266 patients admitted to the ICU were screened, and 111 of these patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: 104 patients remained on EN for less than five days, and seven patients were less than 18 years of age. Thus, 155 patients were included in the study.

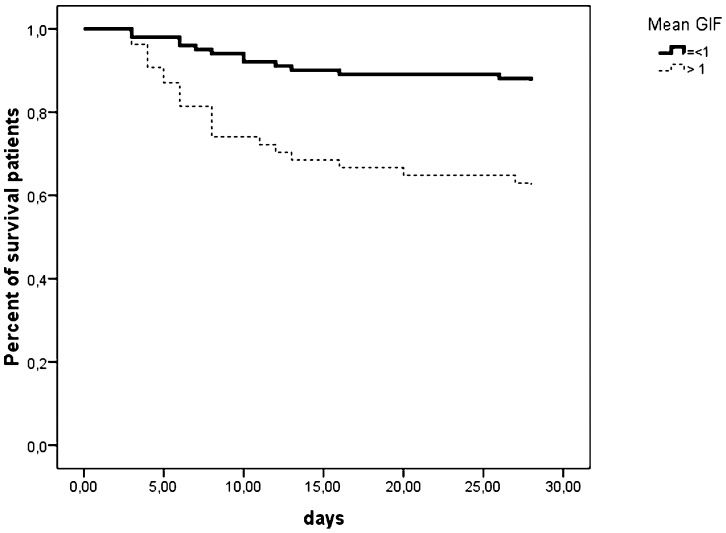

The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients who did not survive presented higher APACHE II and SOFA scores, and more frequently required mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor drugs (Table 1). The mean, worst and categorical GIF scores were associated with lower survival in these patients (Table 1). The results of the regression analyses are presented in Table 2, and in both generated models, the categorical GIF score was independently related to mortality.

Univariate analyses of the characteristics associated with 28-day mortality.

| Non-survivor (n = 67) | Survivor (n = 88) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs (means±SD) | 60 ± 15 | 57 ± 16 | 0.26 | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 38 (57) | 52 (59) | 0.76 | |

| Type of admission, n (%) | ||||

| Medical | 40 (60) | 43 (49) | 0.22 | |

| Surgical | 27 (40) | 45 (51) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation during ICU stay, n (%) | 54 (80) | 54 (61) | 0.01 | |

| Vasopressor use during ICU stay, n (%) | 42 (63) | 35 (40) | 0.005 | |

| APACHE II, points (means±SD) | 19±7 | 16±8 | 0.004 | |

| SOFA D1, points (means±SD) | 6.9±4 | 4.4±3 | 0.0001 | |

| Mean GIF score, points (means±SD) | 1.3±0.8 | 0.5±0.5 | 0.0001 | |

| Worst GIF score, points (means±SD) | 1.9±1.2 | 1.1±1.0 | 0.0001 | |

| Worst GIF score, n (%) | 25 (37) | 76 (86) | <0.0001 | |

| 0 or 1 | 42 (63) | 12 (14) | ||

| >1 | ||||

yrs = years; APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Disease classification system II; SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment; GIF = gastrointestinal failure; SD = standard deviation.

Binary logistic regression of factors associated with mortality.

| Variables | Model containing APACHE II | Model containing SOFA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.60 | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | 0.26 |

| Type of admission | ||||

| Medical | 1.00 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.51 |

| Surgical | 0.47 (0.20–1.10) | 0.51 (0.22-1.19) | ||

| GIF score | ||||

| 0-1 | 1.00 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.001 |

| >1 | 14.2 (5.8-34.3) | 12.0 (4.9–29.1) | ||

| MV | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 0.046 | 1.00 | 0.026 |

| Yes | 2.61 (1.01–6.72) | 3.01 (1.14–7.98) | ||

| APACHE II, points | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 0.002 | X | X |

| SOFA score, points | X | X | 1.21 (1.08-1.36) | 0.001 |

Model containing the APACHE II score Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit (chi-square = 5.5; p = 0.701); model containing the SOFA score Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit (chi-square = 11.7; p = 0.16). APACHE II, Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; MV, mechanical ventilation; GIF, gastrointestinal failure.

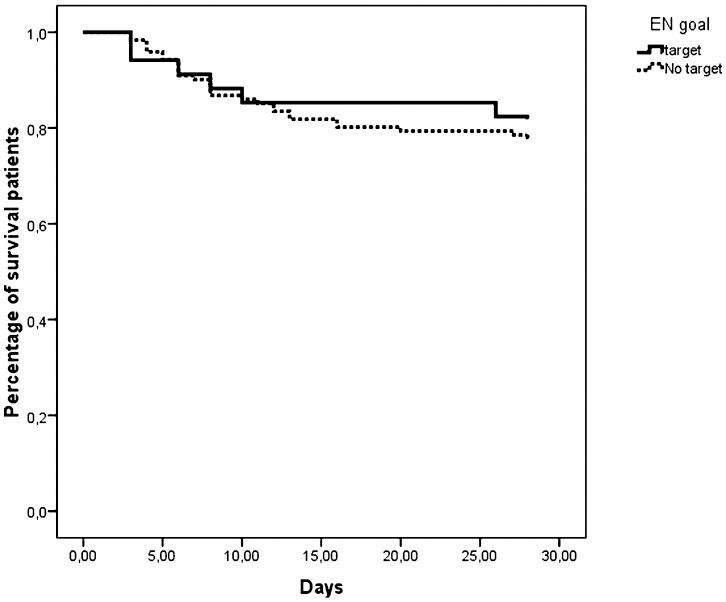

Based on these results, we determined whether patients who had a GIF score of 0 during the entire period of EN support presented lower mortality. As shown in Figure 1, patients who always reached the EN target (n = 34, 22%) did not present lower mortality (p = 0.056). When patients were stratified using the categorical GIF score, lower mortality was observed in patients within the lower strata (Figure 2).

The present study demonstrated that the difference between prescribed and received EN, without the need for intra-abdominal pressure measurement, is a useful marker of prognosis and can be related to GIF in ICU patients.

GIF is a relevant clinical predictor of mortality in general critically ill patients receiving EN and can be quantified using readily available information. Intestinal function is an important determinant of outcomes in critically ill patients, and GIF occurs commonly and is related to worse outcomes (7). One of the major problems in EN strategies is insufficient caloric intake. In the present study, the nutrition target was achieved during the entire period of EN support in only 22% of the patients. Villet et al verified that persistent hypocaloric feeding and negative energy balances were associated with poor outcome in critically ill patients (20). In addition, hypocaloric feeding is associated with the increased incidence of bloodstream infections (21,22). In contrast, some reports did not support the relationship between meeting caloric requirements and mortality (23,24). In fact, a single-center randomized trial suggested that permissive underfeeding is associated with lower mortality rates compared with target feeding (25).

Despite the suggested importance of GIF, there is no consensus method for obtaining a precise assessment of gastrointestinal function. Furthermore, gastrointestinal function is not included in any of the scoring systems used to assess organ failure in ICU patients. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies from one research group have applied a clear definition of GIF and developed a scaled system score. In a retrospective study, Reintam and colleagues demonstrated that a GIF score based on food intolerance, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and/or ileus was able to predict mortality and was associated with longer ICU stays and mechanical ventilation (26). This group also performed a prospective study and demonstrated that a GIF score based on food intolerance and intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) predicts mortality in critically ill patients (18). Thus, we suggest that the difference between prescribed and received EN can be a reliable indicator for evaluating intestinal dysfunction in critically ill patients receiving EN, and even in the absence of IAH, measures could be associated with patient prognosis.

Some limitations of our study must be noted. First, this is a single-center study including a relatively small number of critically ill patients; thus, these results must be confirmed in larger samples from several different centers. Second, the GIF score was determined only in patients whose EN was greater than five days. Thus, our results may not be applicable to patients receiving shorter periods of EN, limiting its clinical application. In addition, in contrast to the APACHE II and SOFA scores, which were recorded at ICU admission, we used the mean or the worst GIF score recorded during the entire ICU stay in our analyses. Thus, the magnitude of the impact of the GIF score on mortality could be overestimated by our results. Third, when computing the score, we did not differentiate whether EN was discontinued due to GI intolerance or the necessity of EN interruption for some general circumstances that can occur during ICU stays (such as surgical procedures and exams). Thus, the discontinuation of EN in our study may not necessarily reflect GIF but still impacts patient prognosis. Our results must be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

The determination of the difference between prescribed and received EN is a useful marker of prognosis in ICU patients and is feasible for incorporation into a prognostic score.

Work supported by INCT-TM – CNPq

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Silva MA, Santos SG, Paula MM, Dal Pizzol F, Ritter C, and Tomasi CD conceived the study, participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. Luz G was involved in drafting the manuscript and critically revising it for important intellectual content. Dal Pizzol F had full access to all of the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of all of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.