Giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign, locally aggressive bone tumor that usually affects the metaphysis and the epiphysis of long tubular bones. It is most frequently located around the knee. It is commonly diagnosed in patients between the ages of 20 and 45 years.1 GCT metastasizes merely to the lungs in 2% of cases with unpredictable behavior.

The sternum is infrequently affected by bone tumors. Although uncommon, malignant neoplasms, such as chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, myeloma, and lymphoma, are most likely to occur in this location.2 GCT of the sternum is an even rarer condition,3,4 and only seven cases are well documented in the literature.5–11 The present article describes the clinical and cytogenetic aspects of an additional case of GCT of the sternum occurring in a young male and includes a discussion of the surgical treatment.

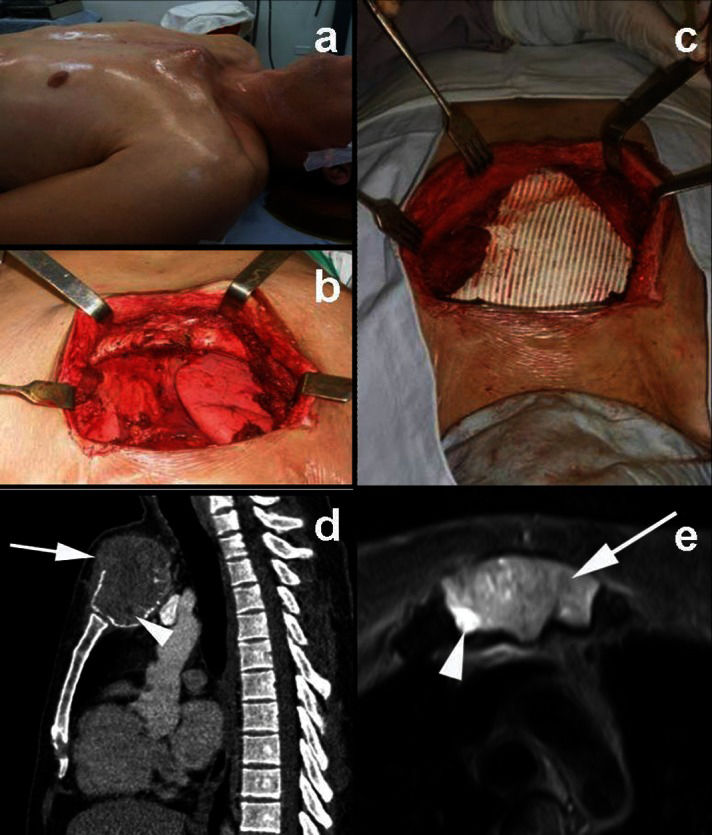

Case ReportA 32-year-old man presented with a sternal mass that had shown progressive growth toward the suprasternal notch over the previous ten months. He complained of local pain that radiated to the cervical region and shoulders. Physical examination showed a bony, tender, six cm large mass of the manubrium (Figure 1A). The patient's pain was increased by palpation and elevation of his arms.

A) Clinical aspect before and after surgery; B) intraoperative aspect after sternum resection; C) intraoperative aspect after reconstruction; and D) CT sagittal reconstruction showing anterior focal cortical bone destruction and soft tissue extension (arrow). In the post-contrast image, it is also possible to identify a small region without contrast enhancement (arrowhead). E) Axial T2-weighted MRI revealed intermediate signal intensity predominance in the sternum giant cell tumor (arrow), although regions of high signal intensity were also present (arrowhead).

Plain radiographs showed an expansile osteolytic lesion of the sternum. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated focal cortical bone destruction, soft tissue extension and subchondral extension in relation to the sternoclavicular joints. CT images confirmed the osteolytic nature of the tumor and the absence of internal mineralization. Post-contrast CT and MRI demonstrated small foci that lacked the enhancement consistent with cystic or hemorrhagic areas. MRI showed that the lesion was of intermediate signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images and included additional areas of high signal intensity on the T2-weighted images (Figure 1D-E).

Histology from a prior biopsy performed at an outside institution revealed a benign tumor composed of multinucleated giant cells compatible with a GCT or a brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism. Laboratory evaluation revealed normal levels of calcium (1.25 MMol/l) and parathyroid hormone (21 PG/ml), making the diagnosis of a brown tumor highly unlikely.

The patient underwent resection of the manubrium with wide margins and post-resection reconstruction with GORE® DUALMESH® PLUS Biomaterial (W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, USA) mesh fixed with polyester separated stitches. Both the clavicles and the first ribs were fixed to the mesh. Thoracic inspection showed no mediastinal or lung nodules. Disarticulation of the body-manubrium joint was uneventful. A bilateral pectoralis major flap covered the mesh and allowed skin closure (Figure 1B-C).

Histological analysis of the resected specimen revealed the presence of multinucleated giant cells, mononucleated small cells and spindle cells with elongated nuclei without atypias. Occasionally, more than 100 nuclei could be perceived in the giant cells, a typical characteristic of GCT (Figure 2A).

A-D) Histological aspect of the lesion showing a triphasic aspect with giant, mononuclear and fusiform cells (B), bone (C) and soft tissue (D) invasion of the tumor, and cystic formations (H&E, A - 400×, B - 200×, C - 100×, D - 100×); E) Cytogenetic analysis of a GCT sample showing a 51, XY, −7, +9, del(10)(q23), add(11)(p15)×2, −15, add(18)(q23), +mar1, +mar2×2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5 karyotype.

The tumor growth had induced extensive bone erosion and focally infiltrated adjacent soft tissues (Figure 2B-C). Blood-filled dilated spaces were seen, suggesting an association with an aneurysmal bone cyst (Figure 2D). Less than one typical mitotic figure was seen per ten high power fields. Atypical mitosis, vascular invasion, and tumor necrosis were not detected.

To allow for cytogenetic studies, a fresh GCT sample (adjacent to areas of the tumor verified by frozen section) was aseptically collected in the operating room and processed as previously described.12 Cytogenetic analysis was performed on 30 metaphases and showed a complex complement characterized by the presence of numerous marker chromosomes. The karyotype was denoted as 51, XY, -7, +9, del(10)(q23), add(11)(p15)x2, -15, add(18)(q23), +mar1, +mar2×2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5 (Figure 2E).

DISCUSSIONIn the seven previously presented cases and this additional case, the median age of diagnosis is 48 years (range: 28 to 74 years); this age is slightly higher than that of GCT patients in general (Table 1).

Reported cases of giant cell tumor (GCT) of the sternum.

| Reference | Gender | Age (years) | Symptom | Location | Size (cm) | Surgery | Reconstruction | Follow-up (months) | Cytogenetic study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sundaram et al., 1982 | m | 55 | painless | manubrium | NA | subtotal sternectomy | none | NA | No |

| Bay et al., 1999 | f | 49 | pain | manubrium | 3.9×3.2 | subtotal sternectomy | prosthesis | 60 | Yes |

| Segawa et al., 2004 | m | 55 | pain | body | 3.5×3.0 | curretage | PMMA | 12 | No |

| Imai et al., 2006 | m | 45 | pain | body | 8.5×4.5×2.5 | subtotal sternectomy | prosthesis | 12 | No |

| Futani et al., 2008 | f | 53 | pain | body | 8×4×2.5 | curretage | PMMA | 84 | No |

| Abate et al., 2009 | m | 28 | painful mass | body | 6.4×4.3×4.4 | subtotal sternectomy | prosthesis | 5 | No |

| Faria et al., 2010 | f | 74 | painful mass | body | 12×7.5×4.5 | subtotal sternectomy | fascia lata | 5 | No |

| Current case | m | 32 | painful mass | manubrium | 7,6×5,1×4,7 | subtotal sternectomy | Gore Dualmesh Plus® | 10 | Yes |

Abbreviations: NA, data not available; PMMA, bone cement filling.

Although imaging can strongly indicate GCT, a biopsy is necessary for diagnosis. Biopsy is of particular importance when the neoplasm affects an unusual location. The variety of giant cell-containing bone tumors (including osteosarcoma, chondroblastoma, and aneurysmal bone cysts) can cause biopsies with small sampling or fine-needle aspirations to be misleading.10 Even with larger tumor samples, it may be difficult to distinguish between GCT and parathyroid brown tumor, and it is necessary to examine specific hormone, calcium, and phosphate serum levels.

There is no consensus regarding the optimal surgical treatment of sternal GCT; interventions ranging from simple curettage to wide resection have been proposed.9 Futani et al. suggest that the initial treatment should involve extended curettage followed by filling with bone cement (Polimetilmetacrilate - PMMA). Because local recurrence rates reach approximately 50% due to the locally aggressive behavior of GCTs, more aggressive forms of surgery, such as marginal or wide resection, should be considered.8,9

Futani et al. suggest that a prosthetic replacement is needed after a subtotal sternectomy to protect the lungs, heart, and main vessels as well as to restore functional thoracic movement to prevent paradoxical respiration.9 As described by Gonfiotti et al., we did not use a rigid prosthetic replacement after the partial sternectomy. No respiratory distress was observed in our patient.13

Three of the eight described cases affected the manubrium and were treated by subtotal sternectomy. Reconstructions were performed with prosthetics in one case, with nothing in one case and with a mesh in our case. In the five cases that affected the body of the sternum, two were treated with curettage and PMMA filling and three with subtotal sternectomy and reconstruction (with a prosthesis in two cases and fascia lata in one) (Table 1).

There are only limited data in the literature on chromosomal aberrations in GCT of the bone. Typically, this tumor is characterized by a high frequency of telomeric fusion, which has been implicated in the initiation of chromosomal instability and tumorigenesis.14 Correspondingly, GTG-banding analysis has demonstrated a more frequent involvement of chromosomes 11p, 13p, 15p, 18p, 19p, and 21p in this process.15

Cytogenetic analysis of our sample showed a complex karyotype characterized by the presence of clonal rearrangements and numerous marker chromosomes. In the literature, some clonal aberrations have been described.15–17 Most notably, Bridge et al. demonstrated clonal structural translocations involving 11p15 in more than one patient; this region was also affected in our tumor sample.15 Sawyer et al. described abnormal karyotypes with clonal telomeric fusions involving the short arm of chromosome 11.18 In three of the five cases studied, telomeric fusions of 11pter were apparently the precursor lesions to the progression of sub-clones of 11p with structural chromosomal aberrations.

Sternal GCT is a very rare disease and should be treated with partial sternectomy. Reconstruction may be done with rigid or flexible materials depending on the stability of the chest wall. Biopsy is indispensable, and the ability to differentiate between GCT and hyperparathyroidism depends on blood sampling. Although no association has been established between unfavorable outcomes and chromosomal changes other than telomeric associations, the frequent involvement of 11p15 in clonal rearrangements suggests that chromosomal changes play an important role in GCT initiation and progression. Whether this alteration is associated with this particular tumor location requires further investigation.