The posterior retroperitoneoscopic approach (PRA) is seldom used in our country to perform adrenalectomies, although it offers possible advantages over laparoscopic anterior or lateral access, according to some authors. The aim of this study was to identify those features that determine the most suitable cases to start the implementation of this technique.

MethodsA prospective observational study was performed with a 50-patient cohort. All the cases were operated using the PRA. Sex, age, body mass index (BMI), operative time, left or right side, size and anatomopathological characteristics of the lesion, conversion rates, complications and hospital stay were analyzed.

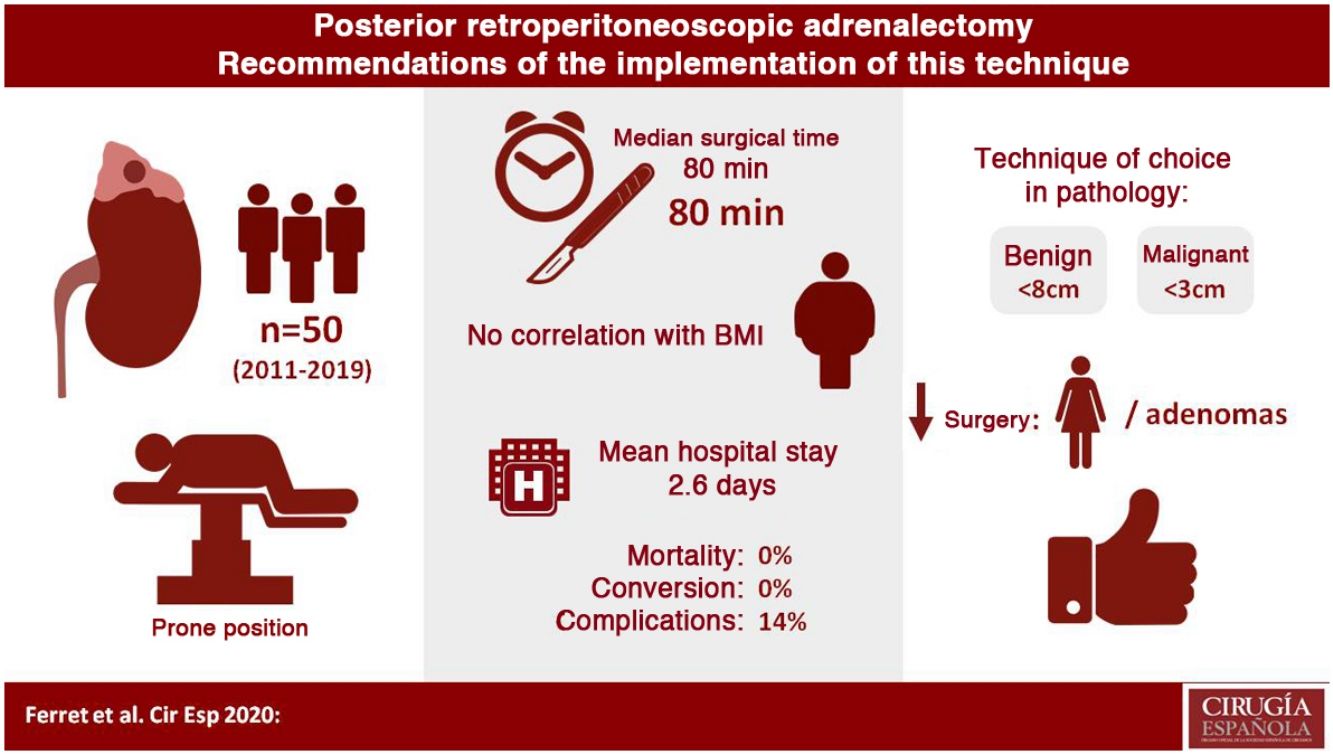

Results25 (50%) women and 25 (50%) men underwent surgery, with a median operative time of 80min (45–180). A significantly shorter operative time (P=.002) was observed in women and in adenomas (P=.002). However, no correlation was observed between surgical time and BMI, lesion side or lesion size. There were no conversions. The complication rate was 14%, and most of the complications were grade I on Clavien–Dindo's scale. Median hospital stay was two days.

ConclusionsRetroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy by posterior approach is a safe and reproducible procedure, with very good outcomes. The most suitable cases to implement this technique would be female patients with adrenal adenomas.

El abordaje retroperitoneoscópico posterior es una técnica poco extendida en España para la suprarrenalectomía a pesar de que, según algunos autores, ofrece ventajas respecto al acceso laparoscópico anterior o lateral. El objetivo del estudio fue identificar aquellas características que permitieran seleccionar los casos más favorables para iniciarse en esta técnica.

MétodosEstudio observacional de una cohorte de 50 pacientes intervenidos mediante suprarrenalectomía retroperitoneoscópica posterior (SRP) en un único centro. Se evaluó: sexo, edad e índice de masa corporal (IMC), tiempo operatorio, lateralidad, tamaño y características anatomopatológicas de las lesiones, tasa de conversión, complicaciones y estancia hospitalaria.

ResultadosSe intervinieron 25 (50%) mujeres y 25 (50%) hombres con un tiempo operatorio mediano de 80 minutos (45-180). Se observó un tiempo operatorio significativamente menor en mujeres (p=0,002) y en adenomas (p=0,002). En cambio, no se observó correlación entre el tiempo quirúrgico e IMC, lateralidad o tamaño de la lesión. No hubo ningún caso de conversión. Las complicaciones fueron del 14% y la mayoría fueron leves, según la Escala de Clavien Dindo (i). La estancia hospitalaria mediana fue de dos días.

ConclusionesLa suprarrenalectomía retroperitoneoscópica por vía posterior es una técnica segura, reproducible y con muy buenos resultados. Los casos más favorables para iniciar la implantación de este abordaje son mujeres con adenomas suprarrenales.

In 1992, Gagner et al.1 described the first laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Since then, numerous articles have been published demonstrating the advantages of this technique over an open approach, including less pain and postoperative ileus, shorter hospital stay and early return to normal daily activity. Initially, it was only indicated for small and benign tumors, but over the years and with improvements made in skills and surgical instruments, it has become the technique of choice.

Several different endoscopic approaches have been described: transperitoneal, lateral retroperitoneal, posterior retroperitoneal, and transthoracic.2–6 The transperitoneal route is one of the most frequently used because it offers a known anatomy and a wide workspace. On the other hand, the posterior retroperitoneal route allows direct and rapid access to the gland without having to enter the peritoneal cavity, thereby avoiding the manipulation of organs such as the liver, pancreas or spleen, reducing surgical time and possible associated complications.7–13

The first posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy (PRA) was published in 1994,14 but it was the Walz et al.15 study in 2006 analyzing a series of 560 procedures that demonstrated important advantages over the laparoscopic approach: 0% mortality, 1.7% conversions to open surgery, and few major complications. For this reason, it is proposed as the approach of choice in adrenal surgery. A meta-analysis published in 2014 by Chai et al.16 compared the transperitoneal route with the posterior retroperitoneal route, concluding that the latter was a faster technique, with less blood loss, less postoperative pain, and earlier discharge from hospital. In 2017, this same group17 carried out a randomized clinical trial with 83 patients, comparing the two approaches and finding no statistically significant differences in operative time between the two groups, although the duration of surgery was longer in male patients or those with pheochromocytomas. In 2014, Barczyński et al.18 published another randomized clinical trial with a total of 65 patients comparing the two approaches, observing a shorter operative time, less blood loss, less postoperative pain and faster recovery in PRA. Kozłowski et al.19 carried out another randomized study in 2019 with 77 patients comparing the two previously mentioned techniques and found no statistically significant differences in terms of operative time, although they did find less postoperative pain and shorter hospital stay in the posterior retroperitoneal route. This group concluded that both routes were effective and safe.

Despite all these studies, this technique is not widely used in Spain. In 2011, the Endocrine Surgery Division of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) published a prospective multicenter study derived from a national survey that analyzed the state of adrenal surgery in Spain at that time.20 None of the 31 hospitals that responded to the survey used the posterior approach, and 84% of the reported procedures were done laparoscopically through a lateral transperitoneal approach, while the remainder were performed by laparotomy.

The objective of this study was to identify the characteristics that allow surgeons to select the most favorable cases to start using this technique.

MethodsWe conducted an observational study of a cohort of 50 patients who underwent PRA in a single tertiary hospital between October 2011 and June 2019. All patients were operated on by the same surgical team, made up of three surgeons from the General and Digestive Surgery Service who underwent training in this technique with Dr. Walz at Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany. From the moment this procedure began, all patients (7–9patients/year) were operated on using this approach, and the three surgeons were gradually incorporated.

Inclusion/Exclusion CriteriaThe surgical indication for adrenal lesions was established after evaluation by the multidisciplinary unit, consisting mainly of endocrinologists, radiologists, and surgeons. Initially, this approach was indicated in patients with small (<4cm)21 and benign lesions, excluding confirmed malignant or highly suspicious lesions. The criteria for suspected malignancy were size, growth, irregular shape, lack of homogeneity, presence of necrosis and calcification, and evidence of invasion. Subsequently, we included medium- and large-sized (>8cm)21 benign lesions and those with malignancy criteria but smaller than 3cm15 that were totally intra-adrenal. The absolute exclusion criteria were patients with large malignant lesions, a history of ischemic heart disease, or cerebrovascular disease. Relative exclusion criteria were pregnancy, extreme obesity (BMI>45), or need for complementary abdominal surgery. No patient presented to the unit met any of the previously mentioned exclusion requirements. Patients with bilateral adrenal adenomas underwent retroperitoneoscopic surgery but were excluded from the analysis of this study.

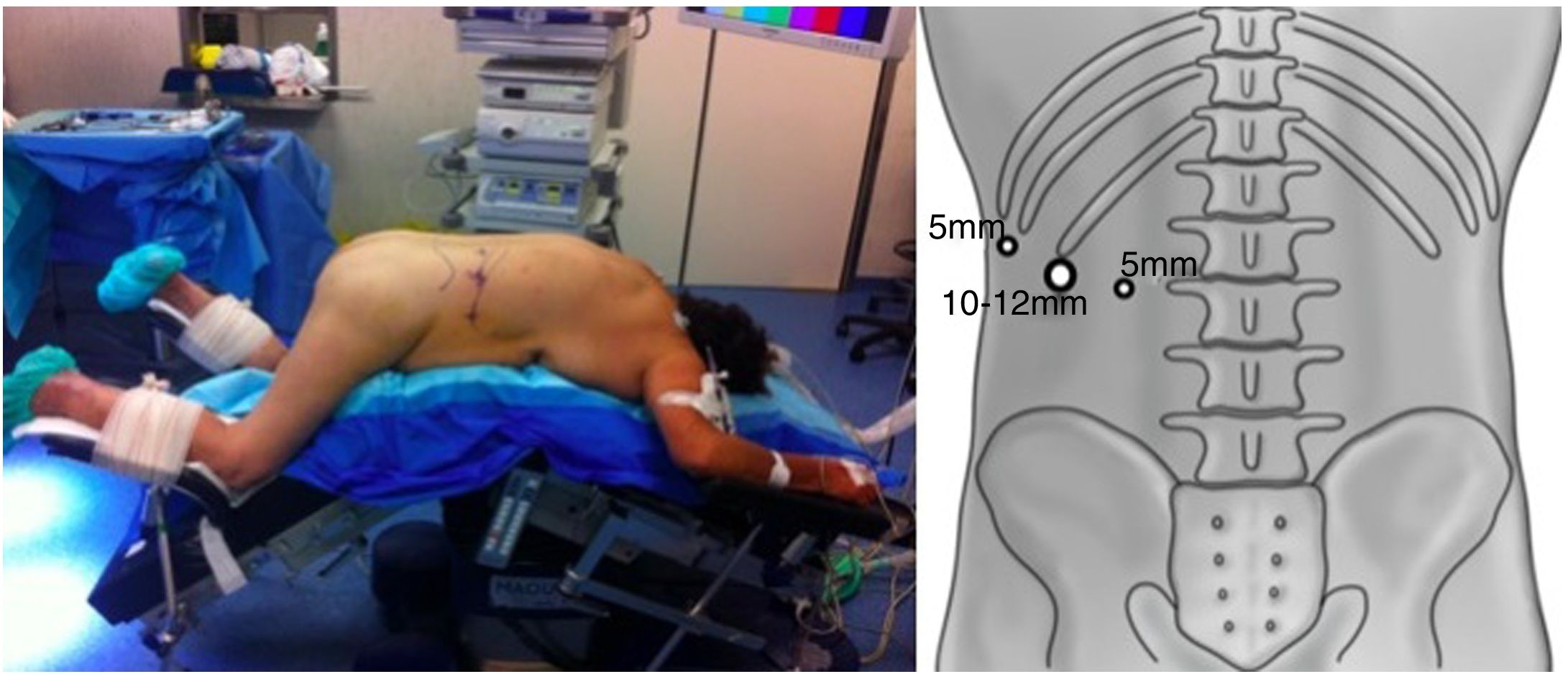

Surgical TechniqueThe patient was placed in the prone position with the hips and knees flexed to correct lumbar lordosis. A 1.5–2cm incision was made just below the tip of the 12th rib. By means of digital dissection, it was possible to separate the muscle fibers and create space to place a lateral 5mm trocar below the 11th rib. A 10–12-mm blunt-tip balloon trocar was placed in the initial incision. Retropneumoperitoneum was created with CO2 at pressures of 20mmHg or higher, if necessary. A third 5- or 10-mm trocar was placed a few centimeters caudal and medial to the initial one (Fig. 1).

After opening Gerota's fascia, we used blunt dissection to identify the kidney, paravertebral musculature, lateral peritoneum, and inferior vena cava in right-side approaches or renal vein in left-side approaches. By displacing the fatty tissue of the upper renal pole caudally, the adrenal gland was usually visualized. Afterwards, the medial arterial vessels were sealed and divided using Ligasure Maryland®, allowing the gland to be displaced laterally and the adrenal vein to be uncovered rather consistently. After sealing and dividing, the dissection of the entire gland was completed en bloc with the surrounding fatty tissue. The piece was extracted in a retrieval pouch through the initial incision, which was able to be expanded when necessary. At the beginning of this series, drain tubes were placed according to the criteria of the main surgeon. In the last 45 cases treated, it was not necessary to place a drain tube in the surgical bed.

Variables StudiedThe variables evaluated included: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), posterior adiposity index (PAI),22–24 surgical time, side of the lesion, size and pathological anatomy, conversion rate, postoperative complications (according to Clavien–Dindo25), and hospital stay. To identify the most favorable patients, the relationship between skin-to-skin surgical times, sex, BMI, PAI, lesion size and pathology results were analyzed. The lesions were classified into three subgroups of adenomas (functioning and non-functioning), pheochromocytomas and other less frequent lesions).

The characteristics of patients with surgical times longer and shorter than the median were also evaluated.

Statistical AnalysisA P<.05 was considered a criterion of statistical significance. The results have been analyzed using the BSD Pandas Open Source® statistical package for Python 3.6 (pandas.pydata.org).

ResultsA total of 50 patients were operated, 25 women (50%) and 25 men (50%), with a median age of 55 years (21–81 years). The median BMI was 28.5kg/m2 (17.7–42.6kg/m2).

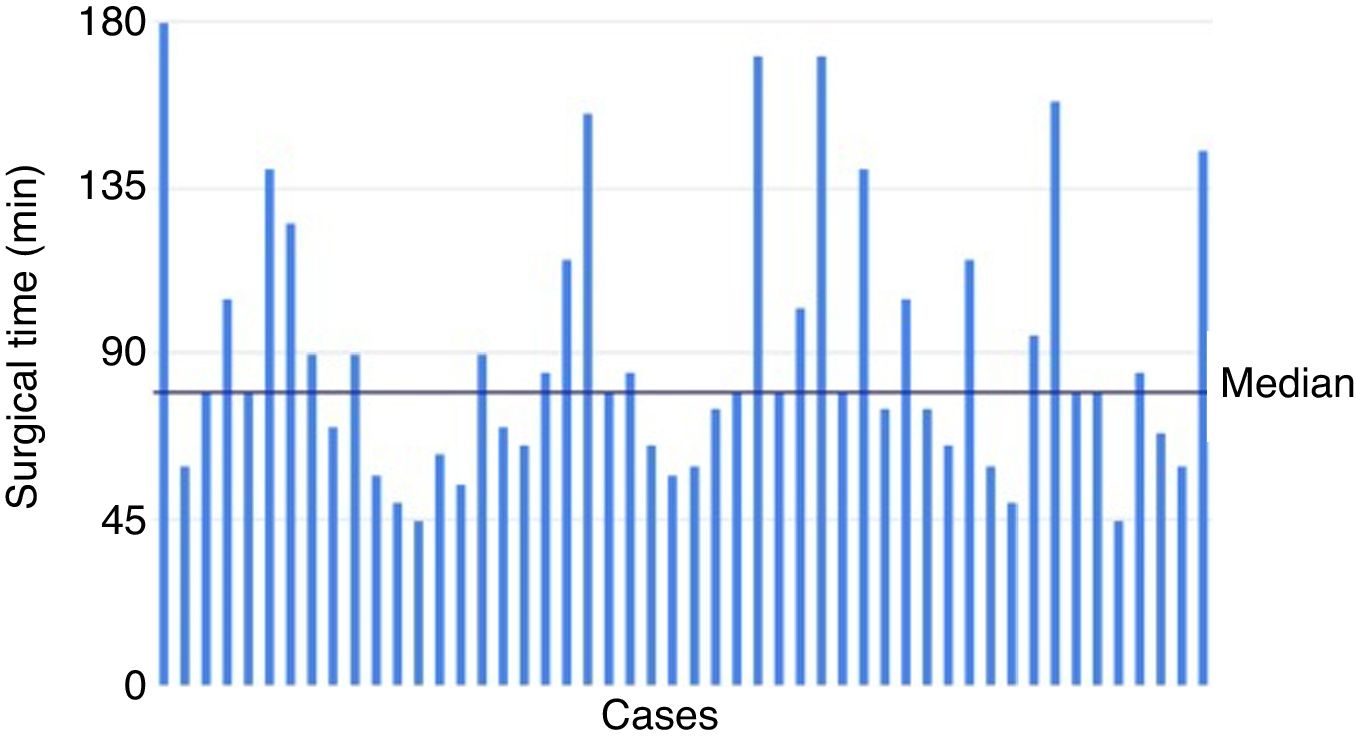

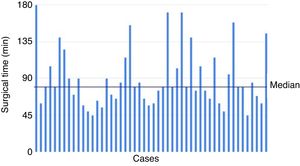

The surgical time of the series ranged between 45 and 180min, with a median of 80min. The evolution of surgical time and its trend can be seen in Fig. 2.

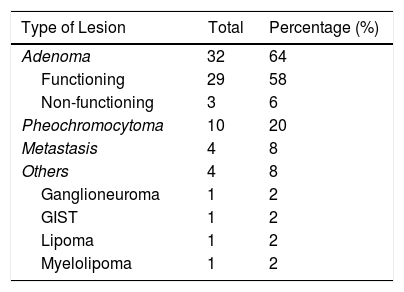

Regarding the side of the lesion, there were 24 right cases (48%) and 26 left cases (52%). The size of the lesions ranged from 0.9cm to 8.8cm, with a median of 2.8cm. The data for the anatomic pathology characteristics of the excised lesions are shown in Table 1. Adenomas were the most frequent lesions, distributed as: 29 (91%) functioning and 3 (9%) non-functioning. Among the functioning adenomas, 16 (55%) were associated with Cushing's syndrome and 13 (45%) primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's syndrome).

In neither case was there a need for conversion. There was no mortality associated with this procedure. In seven cases (14%), there were complications, six of which did not exceed grade I on the Clavien–Dindo scale17: lumbar pain in two patients, incidental opening of the peritoneum in two patients, hypokalemia in one case, and slight hematoma in the surgical wound in another patient. In one patient with accidental opening of the diaphragm, a chest drain tube was required for 48h (Clavien–Dindo IIIa). In the cases with incidental opening of the peritoneum, neither the difficulty of the procedure nor the surgical time appeared to increase; there were also no hemodynamic or ventilatory alterations.

Hospital stay was between one and seven days, with a median of 2 days. Adenomas, with a median stay of 2 days (1–7), had a significantly shorter stay than pheochromocytomas at 3 days (2–5) (P=.017). Within the adenomas, there were no differences (P=.248) in terms of hospital stay according to whether they were functioning (2 days; 1–7) or non-functioning (3 days; 2–4).

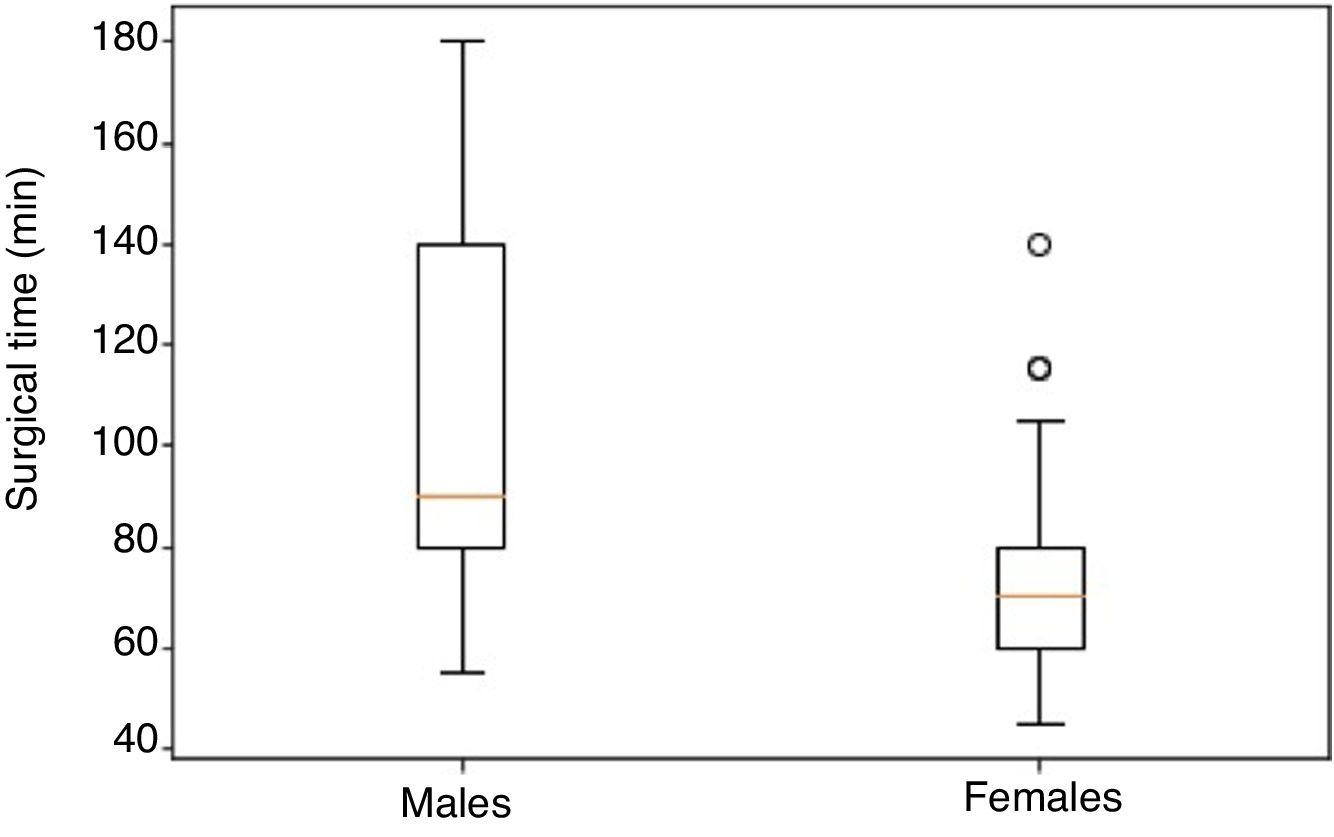

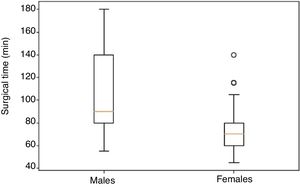

The median surgical time was 70min (45–140) in women and 90min (55–180) in men, which was a statistically significant finding (P=.002) (Fig. 3).

No correlation was observed between surgical time and BMI (Pearson index 0.071) or between surgical time and PAI (Pearson index 0.199). Neither was there a correlation between surgical time and the size of the piece (Pearson index −0.501), nor were significant differences found according to the side of the lesion (P=.340).

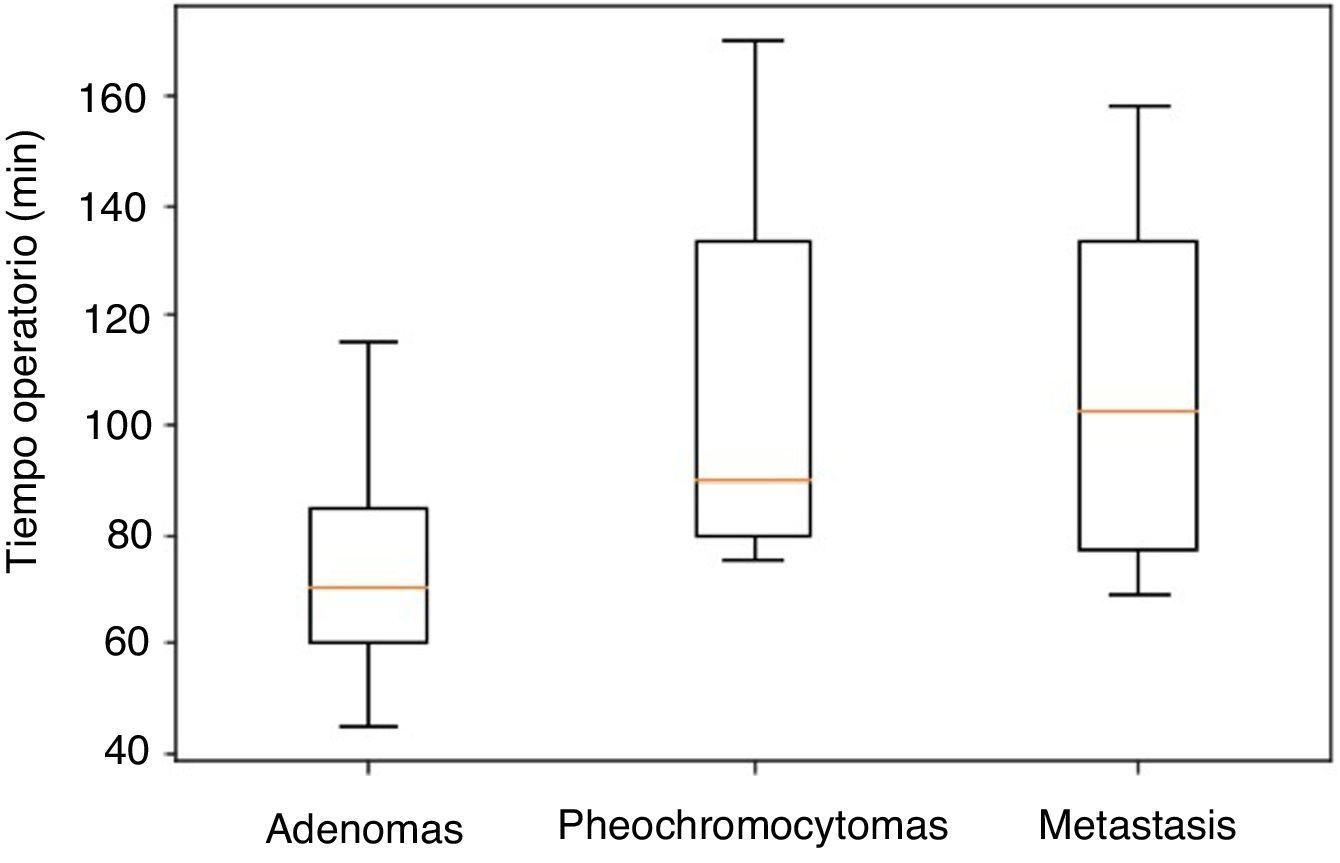

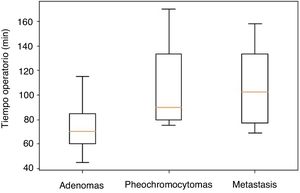

Significant differences were observed in the distribution of operative time according to the pathology results, which was shorter in adenomas vs pheochromocytomas (P=.002), and in adenomas vs metastases (P=.038) (Fig. 4). Specifically, the median operative time for adenomas was 70min (40–170), 90min (80–155) for pheochromocytomas, and 102min (69–158) for metastases. Within the adenomas, the non-functioning lesions had a median operative time of 60min (60–145) and the functioning lesions 75min (45–140); this finding was not statistically significant (P=.500).

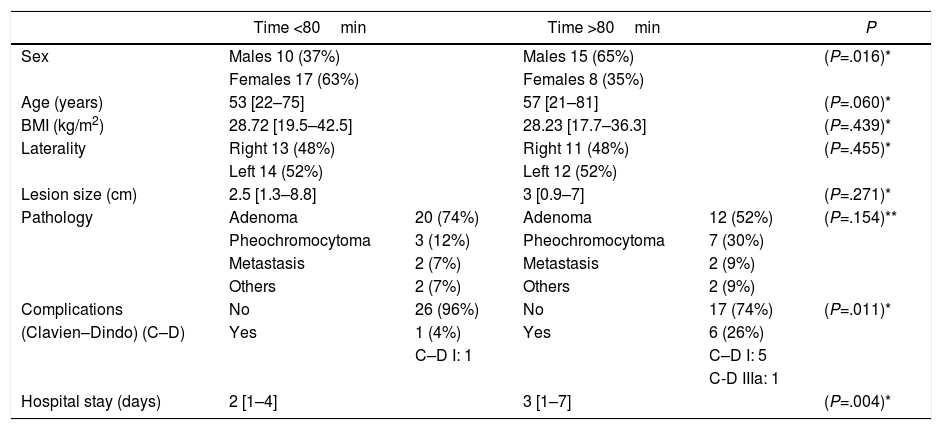

Using the median of 80min as a reference, we compared each of the variables based on said cut-off point. Table 2 presents the results, with a higher proportion of men as well as a higher complication rate and a longer hospital stay in the >80min group.

Results According to Surgical Time Being Longer or Shorter Than the Median (80min); Data Expressed as Absolute Values, Percentage (in Parentheses) and Median [in Brackets].

| Time <80min | Time >80min | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Males 10 (37%) | Males 15 (65%) | (P=.016)* | ||

| Females 17 (63%) | Females 8 (35%) | ||||

| Age (years) | 53 [22–75] | 57 [21–81] | (P=.060)* | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.72 [19.5–42.5] | 28.23 [17.7–36.3] | (P=.439)* | ||

| Laterality | Right 13 (48%) | Right 11 (48%) | (P=.455)* | ||

| Left 14 (52%) | Left 12 (52%) | ||||

| Lesion size (cm) | 2.5 [1.3–8.8] | 3 [0.9–7] | (P=.271)* | ||

| Pathology | Adenoma | 20 (74%) | Adenoma | 12 (52%) | (P=.154)** |

| Pheochromocytoma | 3 (12%) | Pheochromocytoma | 7 (30%) | ||

| Metastasis | 2 (7%) | Metastasis | 2 (9%) | ||

| Others | 2 (7%) | Others | 2 (9%) | ||

| Complications | No | 26 (96%) | No | 17 (74%) | (P=.011)* |

| (Clavien–Dindo) (C–D) | Yes | 1 (4%) | Yes | 6 (26%) | |

| C–D I: 1 | C–D I: 5 | ||||

| C-D IIIa: 1 | |||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 2 [1–4] | 3 [1–7] | (P=.004)* |

One of the limitations of this study is its observational design and no comparison with a control group. Since PRA was started at this hospital in 2011, all patients have undergone posterior surgery, so it has not been possible to carry out a comparative study. Furthermore, due to historical and organizational factors within the hospital, the prior cohort of patients operated on by other approaches is relatively scarce and heterogeneous, so we do not have an adequate historical cohort either.

Regarding the duration of surgery, the mean of this series is around 90min and is similar to times reported by other groups, such as Walz et al.15 (100min for the first 112 cases), Vrielink et al.21 (102min on average) or Lee et al.26 (87min). It was not possible to demonstrate a progressive decrease in surgical time corresponding to the learning curve, as can be seen in Fig. 2. This is probably due to the size of the sample and because the inclusion criteria were modified throughout the process (patients with larger benign and malignant tumors were incorporated as surgeons became more familiar with the technique).

The significantly longer surgical time in male patients is striking, which was also observed by Chai et al.17 This may be explained by anatomical issues, mainly musculoskeletal (lower pelvis in women; often more prominent lumbar muscles in men).

Although some studies describe the influence of BMI on posterior surgical time,15,27 in this series no correlation was found between surgical time and BMI. Regarding PAI, an index established by Lindeman et al.,22 posterior access is discouraged in patients with a PAI above nine. In the series of this article, only two patients presented a PAI greater than nine, and the median was 6.3. The relationship between surgical time and PAI was analyzed, and no increased operative time was found in patients with greater adiposity in the anatomical working area (Pearson's r 0.199). This fact is of great importance since obesity, present in patients with Cushing's syndrome or in the general population, could negatively affect the use of other approaches, such as transabdominal.

There was also no correlation found between the surgical time and the side of the lesion or its size, but there were statistically significant findings regarding the nature of the tumor excised, as adenomas required less surgical time.

The mean stay of 2.6 days was lower than that of the aforementioned study by the Endocrine Surgery Division of the AEC (4.9 days), although this fact could be related to the time lapse between the two studies.

Given the results obtained in this series of 50 cases, the advantages that PRA could offer would be a short surgical time due to direct retroperitoneal access, a low rate of complications by avoiding entry into the abdominal cavity (with no risk of damage of other viscera), and absence of added difficulty in obese patients or with those with previous abdominal surgeries. Specifically, the profile of the most suitable candidate would be a female patient with a lesion compatible with adenoma. Treatment of bilateral adrenal involvement would be facilitated by PRA by not having to mobilize the patient, but these results were not included in the design of this study.

Possible drawbacks in implementing this technique would be the scarce familiarity of surgeons with the retroperitoneal access and the difficulty of training in it, as well as the possible reluctance of anesthesiologists who are not used to working with the patient prone position, large tumors, or malignant pathologies in which there is a risk of not achieving correct oncological results.

To the extent of our knowledge, this study presents the longest series of consecutive patients treated with a posterior approach at a single hospital in Spain. However, it has some limitations, such as the sample size and the extension of the inclusion criteria over time, which entails statistical limitations.

ConclusionsPosterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy is a relatively simple, reproducible, safe procedure with very good results, provided that the cases are appropriately selected, so its implementation in a surgery service is feasible.

Authorship/CollaborationsGeorgina Ferret: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, composition of the article, and review and final approval.

Clara Gené: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, composition of the article, and review and final approval.

Jordi Tarascó: study design, data collection and review and final approval.

Ana Torres: data collection and review and final approval.

Albert Caballero: analysis and interpretation of the results and review and final approval.

Pau Moreno: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, composition of the article, and review and final approval.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr. David Parés and Dr. Joan Francesc Julián for their help and collaboration in reviewing of the article.

Please cite this article as: Ferret Granés G, Gené Skrabec C, Tarascó Palomares J, Torres Marí A, Caballero Boza A, Moreno Santabárbara P. Suprarrenalectomía retroperitoneoscópica por vía posterior. Recomendaciones para la implementación de esta técnica. Cir Esp. 2021;99:289–295.