To determine the incidence of incisional hernia in patients subjected to colorectal cancer surgery. To analyse the individual risk factors and to determine which patients would benefit more from the use of prophylactic measures.

Patients and methodsA retrospective study was performed on the demographic and surgical data, as well as the complications, risk factors and outcomes of all patients subjected to colorectal cancer surgery in the period between January 2006 and September 2008. The diagnosis of incisional hernia was made by means of physical examination or by a review of the follow up CT scan.

ResultsA total of 338 patients were reviewed (249 laparotomy and 89 laparoscopy). After a median follow-up of 19.7 months, 87 patients (25.7%) were diagnosed with incisional hernia by a physical examination. The CT scan enabled 48 hernias (14.2%) not detected clinically. The incisional hernia rate was 39.9% (135 patients). There were no significant differences between patients subjected to laparotomy (40.9%) or laparoscopy (37.1%). The incisional hernia rate in overweight patients (BMI≥25kg/m2) was 51.3% compared to 31.1% in patients with normal weight (P=.02). Post-surgical complications (P=.007), surgical wound infections (P=.04), and further surgery during the post-operative period (P<.0001), were also associated with a higher incidence of incisional hernia.

ConclusionThe prevalence of incisional hernia after colorectal cancer resection is higher than expected (41%). Patients with a BMI greater than 25kg/m2, and those who require further surgery are candidates to receive a prophylactic mesh.

Determinar la tasa de hernia incisional en pacientes intervenidos por neoplasia de colon y recto. Analizar los factores de riesgo individuales y determinar aquellos pacientes en los que pudiera ser adecuado el uso de medidas profilácticas.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de los datos demográficos, quirúrgicos, complicaciones, factores de riesgo y evolución de todos los pacientes intervenidos por cáncer colorrectal en el período entre enero de 2006 y septiembre de 2008. El diagnóstico de hernia incisional se hizo mediante exploración física o mediante revisión de la TAC de seguimiento.

ResultadosSe revisaron un total de 338 pacientes (249 laparotomía y 89 laparoscopia). Tras una mediana de seguimiento de 19,7 meses; 87 pacientes (25,7%) fueron diagnosticados por exploración física de hernia incisional. La TAC permitió diagnosticar 48 hernias (14,2%) no detectadas clínicamente. La tasa de hernia incisional fue del 39,9% (135 pacientes). No hubieron diferencias significativas entre los pacientes intervenidos por laparotomía (40,9%) y laparoscopia (37,1%). En pacientes con sobrepeso (IMC ≥ 25 kg/m2), la tasa de hernia incisional fue del 51,3% frente a un 31,1% en los pacientes con peso normal (p = 0,02). La aparición de complicaciones postoperatorias (p = 0,007); infección de herida quirúrgica (p = 0,04); y reintervención durante el periodo postoperatorio (p < 0,0001) también se asoció a mayor tasa de hernia incisional.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de hernia incisional tras resección por cáncer colorrectal es superior a la esperada (41%). Los pacientes con un IMC superior a 25 kg/m2 y los que precisan reintervención son candidatos a recibir una malla profiláctica.

In spite of the existence of a series of patient groups who are at high risk of developing complications related to abdominal wall closure, such as eviscerations1–2 and incisional hernia,3–5 there is no consensus with regard to the measures for prevention, except in very specific cases such as morbid obesity,6 aortic aneurysm7 and colostomies.8–10

For patients at high risk, some authors advocate the use of prophylactic mesh, and prospective studies have shown an improvement in the rates of incisional hernias,11–13 although in some situations the use of mesh is controversial because of the potential increase in the frequency of complications.14

The incidence of incisional hernia is variable after laparotomy, between 2% and 20%.15–17 This variability is probably because the studies include, all types of laparotomies, diseases, approaches and follow-up methods, which contribute to a lack of homogeneity when the results are compared. As such, the true incidence of incisional hernias is probably underestimated.18

Incisional hernias have important consequences on morbidity, quality of life and healthcare costs,19 and therefore developing preventive measures for high risk patient groups and surgery is fully justified.13,14

Patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer form a subgroup of patients in whom the development of incisional hernias in the long term is very probable.20 Specific studies analysing incisional hernia incidence after midline laparotomy in these patients are scarce and report figures between 9% and 33%.20–24

The aims of this study were to determine the frequency of incisional hernia in a cohort of consecutive patients undergoing surgery for to colorectal cancer who survived for at least one year after surgery; and to analyse the associated risk factors in an attempt to determine patients who could be candidates for the use of prophylactic measures in the primary surgical procedure.

Patients and MethodsThe medical records of patients undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer between January 2006 and September 2008 were retrospectively reviewed. All the surgeries were performed by the same team of surgeons. The decision regarding the approach was based on the experience of the surgeon in minimally invasive techniques, the size of the tumour, the underlying comorbidities and the existence of previous abdominal surgery.

All patients received bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol, thromboembolism prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin and antimicrobial prophylaxis with gentamicin and metronidazole. For laparoscopic surgery, all trocar sites greater than 5mm were closed with interrupted Vicryl no 1 sutures (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA), and incisions for assistance were closed with a continuous polydioxanone no 1 suture (PDS) (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The open resections were performed by midline laparotomy, closing the wall with a continuous polydioxanone no 1 suture (PDS) (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA).

The following information was recorded: demographic data, patient risk factors, surgical data, postoperative complications and subsequent treatment of the oncologic disease. The data was compiled from the patients’ computerised medical record in which events were recorded at the time of their occurrence, and from our Department's colorectal surgery prospective database:

The criteria for diagnosis of incisional hernia were:

- 1)

Clinical diagnosis during postoperative follow-up.

- 2)

A defect in the abdominal wall visible in the control CT scan, located in the area of the surgical scar, accompanied by a protrusion through the defect.

The CT scans were analysed by an independent observer. The cases classified as doubtful were revised by a second observer and only those in which the 2 observers concurred were considered positive.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 15.0 software (IBM Inc., Rochester, MN, USA). The quantitative variables are presented as mean±standard deviation and the qualitative variables as proportions. The association between qualitative variables was analysed using contingency tables (χ2 test and Fisher's exact test when necessary), and between quantitative variables by Student's t-test for unpaired data, or Mann–Whitney test when necessary. The normality of the quantitative variable distribution was verified with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Statistical significance was established at P<.05.

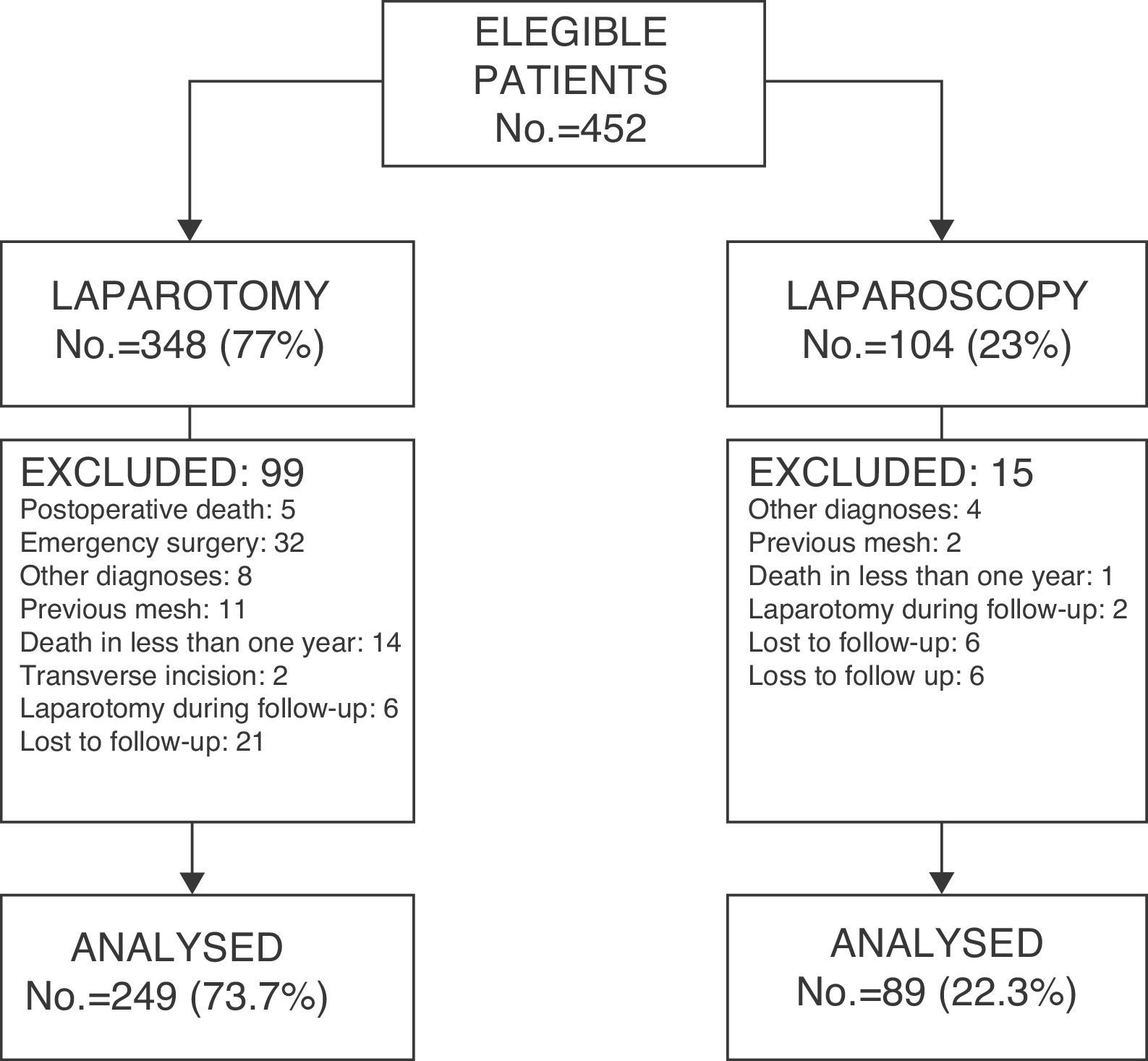

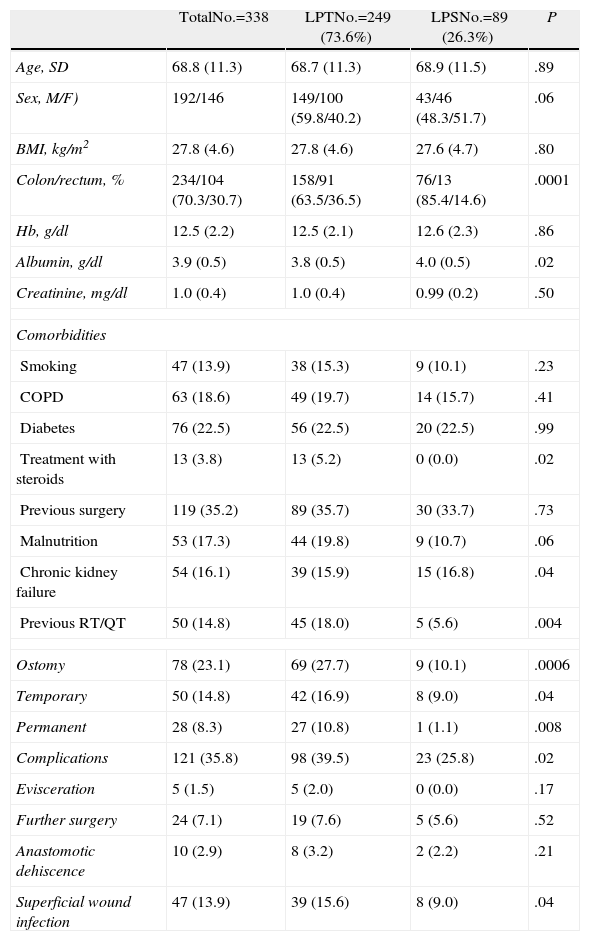

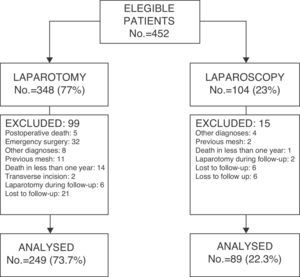

ResultsThe medical records of 452 patients who underwent surgery (348 by laparotomy and 104 by laparoscopy) were analysed and 114 of them were excluded (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the patients and the comparison between groups operated on by laparotomy (LPT) and those operated on by laparoscopy (LPS). The conversion rate was 10.1% (9 of 89).

Characteristics of the Patients.

| TotalNo.=338 | LPTNo.=249 (73.6%) | LPSNo.=89 (26.3%) | P | |

| Age, SD | 68.8 (11.3) | 68.7 (11.3) | 68.9 (11.5) | .89 |

| Sex, M/F) | 192/146 | 149/100 (59.8/40.2) | 43/46 (48.3/51.7) | .06 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8 (4.6) | 27.8 (4.6) | 27.6 (4.7) | .80 |

| Colon/rectum, % | 234/104 (70.3/30.7) | 158/91 (63.5/36.5) | 76/13 (85.4/14.6) | .0001 |

| Hb, g/dl | 12.5 (2.2) | 12.5 (2.1) | 12.6 (2.3) | .86 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.9 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.5) | .02 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.99 (0.2) | .50 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Smoking | 47 (13.9) | 38 (15.3) | 9 (10.1) | .23 |

| COPD | 63 (18.6) | 49 (19.7) | 14 (15.7) | .41 |

| Diabetes | 76 (22.5) | 56 (22.5) | 20 (22.5) | .99 |

| Treatment with steroids | 13 (3.8) | 13 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | .02 |

| Previous surgery | 119 (35.2) | 89 (35.7) | 30 (33.7) | .73 |

| Malnutrition | 53 (17.3) | 44 (19.8) | 9 (10.7) | .06 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 54 (16.1) | 39 (15.9) | 15 (16.8) | .04 |

| Previous RT/QT | 50 (14.8) | 45 (18.0) | 5 (5.6) | .004 |

| Ostomy | 78 (23.1) | 69 (27.7) | 9 (10.1) | .0006 |

| Temporary | 50 (14.8) | 42 (16.9) | 8 (9.0) | .04 |

| Permanent | 28 (8.3) | 27 (10.8) | 1 (1.1) | .008 |

| Complications | 121 (35.8) | 98 (39.5) | 23 (25.8) | .02 |

| Evisceration | 5 (1.5) | 5 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | .17 |

| Further surgery | 24 (7.1) | 19 (7.6) | 5 (5.6) | .52 |

| Anastomotic dehiscence | 10 (2.9) | 8 (3.2) | 2 (2.2) | .21 |

| Superficial wound infection | 47 (13.9) | 39 (15.6) | 8 (9.0) | .04 |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

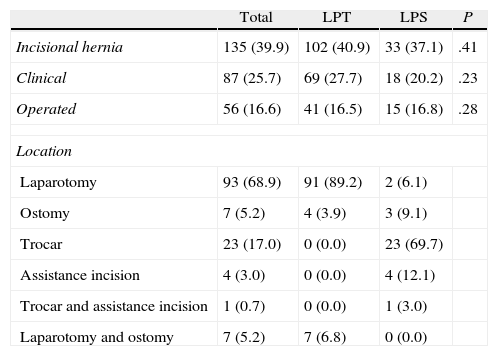

In the 338 patients considered valid, after a median follow-up of 19.7 months (min. 12m; max. 47.1m), a total of 87 (25.7%) were clinically diagnosed with incisional hernia; 56 patients (41 LPT and 15 LPS) underwent surgical repair and the rest did not have further surgery for various reasons (Table 2).

Incisional Hernias.

| Total | LPT | LPS | P | |

| Incisional hernia | 135 (39.9) | 102 (40.9) | 33 (37.1) | .41 |

| Clinical | 87 (25.7) | 69 (27.7) | 18 (20.2) | .23 |

| Operated | 56 (16.6) | 41 (16.5) | 15 (16.8) | .28 |

| Location | ||||

| Laparotomy | 93 (68.9) | 91 (89.2) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Ostomy | 7 (5.2) | 4 (3.9) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Trocar | 23 (17.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Assistance incision | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Trocar and assistance incision | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Laparotomy and ostomy | 7 (5.2) | 7 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

LPS: laparoscopy; LPT: laparotomy.

The study of the follow-up CT scans resulted in the diagnosis of 14.2% additional hernias (33 LPT and 15 LPS) not detected clinically, which increased the rate of the series to 39.9% (135 patients). This means that a third of the hernias were not detected during the clinical follow-up, and were only detected on examination of the imaging scans.

When the approaches were compared (Table 2), no significant differences in the incidence of incisional hernias were detected. Clinical detection was higher in patients who underwent laparotomy but without significant differences (67.6% vs 56.2%; P=.28).

With regard to location (Table 2), 96.0% of the incisional hernias of the LPT group patients were midline abdominal hernias (39.3% of the total). Eleven patients (10.7% of the hernias) of this group presented an incisional hernia in the area of an stoma (4 isolated and 7 combined with hernia in the laparotomy). This means a hernia rate of 15.9% at the ostomy site (11/69 patients). 72.7% (24 patients) of incisional hernias of the LPS group were located at the trocar sites, whether in isolation (23 patients) or combined (one patient). Five patients (15.1% of the total hernias) presented incisional hernias in the area of the assistance incision (4 isolated and one combined) and 3 patients at the ostomy site, which is 33.3% of the ostomised patients in this group.

The total rate of incisional hernias in patients who underwent a stoma (both temporary and permanent) was 17.9%. Six (21.4%) of the 28 patients who underwent a permanent stoma in the initial surgery, developed a parastomal hernia. Patients who had a temporary stoma presented an incisional hernia rate of 16% (8/50) at the previous ostomy wound, after restoration of bowel continuity,.

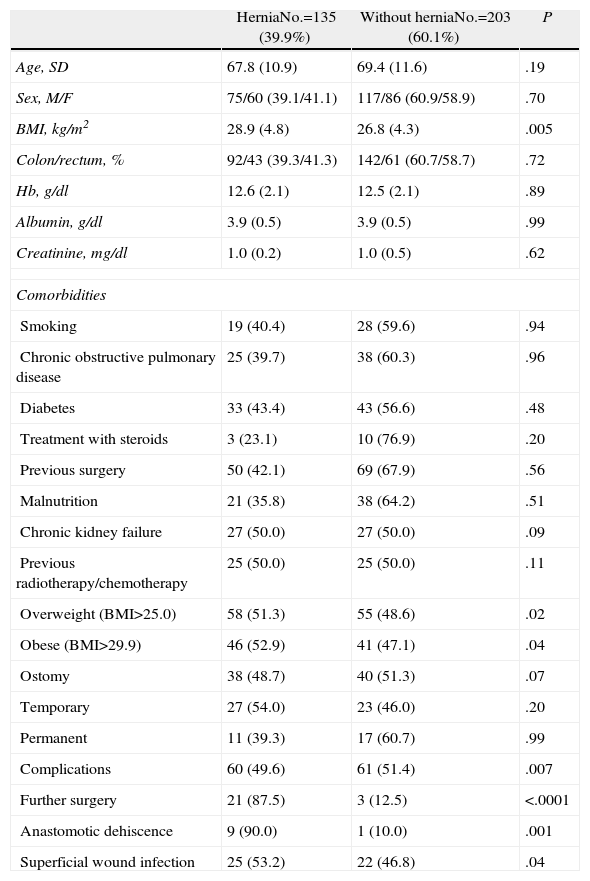

The comparison of the risk factors potentially associated with the development of incisional hernias (Table 3) demonstrated statistically significant differences in the body mass index (BMI) (P=.005). When a comparison was made between overweight patients (BMI>25) and those of normal or below normal weight, significant differences were also found (overweight 51.3% vs normal weight 31.1%; P=.02).

Comparison of Risk Factors.

| HerniaNo.=135 (39.9%) | Without herniaNo.=203 (60.1%) | P | |

| Age, SD | 67.8 (10.9) | 69.4 (11.6) | .19 |

| Sex, M/F | 75/60 (39.1/41.1) | 117/86 (60.9/58.9) | .70 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.9 (4.8) | 26.8 (4.3) | .005 |

| Colon/rectum, % | 92/43 (39.3/41.3) | 142/61 (60.7/58.7) | .72 |

| Hb, g/dl | 12.6 (2.1) | 12.5 (2.1) | .89 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.9 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.5) | .99 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.5) | .62 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Smoking | 19 (40.4) | 28 (59.6) | .94 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25 (39.7) | 38 (60.3) | .96 |

| Diabetes | 33 (43.4) | 43 (56.6) | .48 |

| Treatment with steroids | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | .20 |

| Previous surgery | 50 (42.1) | 69 (67.9) | .56 |

| Malnutrition | 21 (35.8) | 38 (64.2) | .51 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 27 (50.0) | 27 (50.0) | .09 |

| Previous radiotherapy/chemotherapy | 25 (50.0) | 25 (50.0) | .11 |

| Overweight (BMI>25.0) | 58 (51.3) | 55 (48.6) | .02 |

| Obese (BMI>29.9) | 46 (52.9) | 41 (47.1) | .04 |

| Ostomy | 38 (48.7) | 40 (51.3) | .07 |

| Temporary | 27 (54.0) | 23 (46.0) | .20 |

| Permanent | 11 (39.3) | 17 (60.7) | .99 |

| Complications | 60 (49.6) | 61 (51.4) | .007 |

| Further surgery | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | <.0001 |

| Anastomotic dehiscence | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | .001 |

| Superficial wound infection | 25 (53.2) | 22 (46.8) | .04 |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

Likewise the occurrence of postoperative complications (P=.007), the superficial infection of the surgical wound (P=.04), further postoperative surgery (P<.0001) and anastomotic dehiscence (P=.001) showed significant correlation with the development of an incisional hernia.

The presence of multiple comorbidities was associated with a higher frequency of incisional hernia but without achieving statistical significance. Patients with more than 3 comorbidities presented 45.3% of incisional hernias (39/86) and the group with less than 3 comorbidities had an incidence of 38.1% (96/252).

DiscussionOur results show a high rate of incisional hernias after colorectal resection for cancer (39.9%). Other studies on incisional hernias offer variable data in terms of incidence, with a range between 2% and 20% in elective laparotomy, including all types of patients, approaches, diseases and diverse follow-up systems.15,18,25,26

In the analysis of our series, the only individual factor associated with a higher rate of incisional hernia was obesity. A BMI greater than 25kg/m2 has been revealed as a predisposing factor in the development of incisional hernia. This has been previously demonstrated4 and, as such, prospective studies should be carried out to determine if the use of prophylactic mesh is able to prevent incisional hernias in these patients.

Other comorbidities such as smoking, COPD, diabetes, malnutrition, immunosuppression or chronic kidney failure, associated in literature6 with a greater risk of suffering an incisional hernia, did not demonstrate a significant association in the present study (Table 3). This coincides with other prospective studies.4 In patients who showed a high number of associated comorbidities, no significant differences were noted in the incidence of incisional hernias (fewer than 3 comorbidities 38.1% vs more than 3 comorbidities 45.3%; P=.2), but this trend and the greater frequency of complications that take place in these patients suggest that for this group, it would be advisable to study the use of prophylactic measures at the initial surgery.

It has also been previously shown that there is a significant link between postoperative complications in general and the presence of certain complications such as surgical wound infection, anastomotic dehiscence and reoperative surgery. The 2 latter factors are almost unavoidably associated with incisional hernias that appeared in practically 90% of the cases; we cannot compare our results with those of other authors because there are no specific previous studies on the link between incisional hernia, anastomotic dehiscence and further surgery. From our data, the use of preventive measures should be assessed in these patients when performing reoperative surgery, although since it is a frequently contaminated area it would not be advisable to systematically use a prophylactic mesh. In the future, safe devices should be developed for use in this type of situation: as such, biological mesh or mesh impregnated with antiseptic and/or antibiotic substances could be useful and should be assessed in prospective studies.

Surgical wound infection has been described in several previous studies4 as a predisposing factor in percentages that fluctuate between 21.7% for a superficial infection and 50% for a deep infection. In our study, 53.2% of patients wound infection developed incisional hernias. Introducing improvement measures to prevent the infection of the surgical site will produce a significant decrease in incisional hernias. Topical antibiotic treatment after surgery has been assessed recently for the prevention of wound infection without any significant improvement.27

The main question deriving from our study is if the results demonstrated could be the product of errors in the closure technique. In all cases the same technique and the same materials were used. Obviously, given that it is a retrospective study, we cannot, with certainty, provide data regarding whether the 4:1 relationship was strictly maintained as is stated in the literature, but all participating surgeons know this rule and routinely use 2 sutures of 75cm, each of which should be sufficient to maintain this relationship. This highlights the need to invest in the design and research of closure or closure assistance systems that go beyond needles and sutures.

The high prevalence of incisional hernias in our study is certainly influenced by the use of CT scans. Its use allowed the identification of 35.1% of hernias that had not been noticed during the follow-up. This would have resulted in an incidence of 25.7%, which is not very far off the incidence described in the literature. This was also observed in other studies,10 which certifies that in order to know the real frequency of incisional hernias, clinical examination is not sufficient. Future studies on incisional hernias must base their data on the confirmation of the hernia using imaging techniques.

The use of laparoscopy for colonic resection has been associated, according to some authors, with a decrease in the prevalence of incisional hernias.22,24 The lack of differences in our study confirms the data of other recent studies.20,23,24 The significant differences between groups should favour the LPS group which should present a lower rate of incisional hernias (Table 1). It is likely that the low incidence reported initially21,22 has increased as the indications for LPS have increased and operations have been performed on more difficult patients with a higher number of risk factors. Because of this patients operated on laparoscopically should undergo the same preventive measures as patients who undergo surgery by laparotomy, both for trocar sites and assistance incisions.

The main defect of our study is its retrospective nature. However, the data has been obtained from the patients’ clinical records, which offers high reliability, since they were recorded in the moment they occurred and has allowed practically all the data of the patients to be recovered.

The high number of patients studied, the follow-up of at least a year in all of them and the analysis based on image tests are strong points of the study, although the use of CT may produce a bias in overdiagnosing incisional hernias that may not be noticed clinically and may not require treatment.

In conclusion, the high rate of incisional hernias found makes it advisable to consider the use of prophylactic measures, such as the use of a mesh in patients with a BMI>25. Patients who require reoperative surgery should receive a prophylactic mesh whenever possible. A randomised prospective study seems essential in view of the data provided.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please, cite this article as: Pereira JA, et al. Elevada incidencia de hernia incisional tras resección abierta y laparoscópica por cáncer colorrectal. Cir Esp. 2013;91:44–9.