A ventilated facade can be understood as a cladding system fixed to the external wall of the building using mechanical anchor points. The ventilated facade, in addition to its aesthetic effect, improves the thermal (thermal comfort), acoustic and energy efficiency performance of the building. The ventilated facade (or facade) system (VFS) is a construction alternative using non-adhered industrialised elements. Its use has increased substantially in recent years and it has been chosen by architects as a suitable solution for retrofitting existing buildings and for buildings to be built. It is an envelope solution that is suitable for a variety of building types, climates and design configurations. The influence of VFS on the thermal, energy and acoustic performance of buildings is a current topic of research and can be characterised as a sustainable solution in the construction industry. The aim of this article is to present the state of the art of current literature on the application of VFS technologies, in terms of thermal, energy and acoustic analysis, the performance of different coatings applied, fixing systems and the advantages and disadvantages of the system, in order to provide guidelines for future studies and projects.

Una fachada ventilada puede entenderse como un sistema de revestimiento fijado a la pared exterior del edificio mediante puntos de anclaje mecánicos. La fachada ventilada, además de su efecto estético, mejora las prestaciones térmicas (comodidad térmica), acústicas y de eficiencia energética del edificio. El sistema de fachada ventilada (o fachada) (SFV) es una alternativa constructiva que utiliza elementos industrializados no adheridos. Su uso se ha incrementado sustancialmente en los últimos años, y ha sido elegido por los arquitectos como una solución adecuada para la rehabilitación de edificios existentes, y para edificios por construir. Es una solución de envolvente adecuada para una gran variedad de tipos de edificios, climas y configuraciones de diseño. La influencia del SFV en el rendimiento térmico, energético y acústico de los edificios es un tema actual de investigación, y puede caracterizarse como una solución sostenible en el sector de la construcción. El objetivo de este artículo es presentar el estado actual de la literatura sobre la aplicación de las tecnologías del SFV, en términos de análisis térmico, energético y acústico, el rendimiento de los diferentes revestimientos aplicados, los sistemas de fijación y las ventajas e inconvenientes del sistema, con el fin de proporcionar directrices para futuros estudios y proyectos.

Architecture is constantly evolving, adapting to the cultural and technological trends experienced over time. As a result, there is a need to develop new solutions for building systems and overcome challenges in design, construction and operations, especially in the case of facades and especially in relation to performance. The facade is one of the building's basic elements. For architecture, the facade of a building, in addition to its aesthetic effect, is also important due to its impact on energy efficiency [1] and represents the link between external environmental factors and the internal demands of users [2]. Facade cladding systems have a significant effect on the performance and durability of buildings, contributing to watertightness, property valuation and aesthetic finish [3]. In addition, it determines user satisfaction in relation to perceived serviceability and safety under operational conditions, offering basic requirements related to water non-permeability, fire resistance and overall structural performance [4].

Conventional facades with adhered coatings have a high incidence of pathologies [5] and delays in completion. Weathering processes, deterioration of materials, problems with humidity, resulting in wear and tear of joints and seals, corrosion of metal parts, degradation of insulation and conditions of use reduce the facade's performance over time [6]. The conventional building skin facades are also known for presenting numerous problems, such as glare, especially in buildings with a high glazing layer located in hot climate regions, and reduced thermal comfort, resulting in increased energy consumption through the use of air conditioning units [7].

The facade has evolved in complexity over time, encompassing functionality and high performance [6]. In addition, it usually avoids the presence of moisture in the walls of buildings that causes deterioration of materials and impacts on human health [8]. Design and application of new facade concepts are fundamental and must be able to provide security, mitigation of air and water infiltration, thermal and acoustic insulation, solar control, natural lighting, glare control, pleasing aesthetics and, at the same time, minimise energy demand [6,9].

Buildings represent the main energy demand in many countries. Thus, the generation and use of green energy, sustainable energy solutions, responsible building systems and reducing carbon emissions have become important issues that have been debated frequently in recent years by government and non-government leaders [10], and can be associated with new elements of construction, especially VFS.

Sustainable development requires the creation of innovative facades that can harmonise the relationship between people and the natural environment [1], with a focus on smart facades in the architectural sector [11]. These facades combine resources, materials and technologies that alter their properties with changes in climate and/or occupancy, with the aim of maintaining the occupant's internal comfort while being subject to minimal energy demand [12]. These factors (resources, materials and technology) have fostered the evolution of complex multi-layer facade constructions with components designed to fulfil specific functions. Intelligent facades facilitate dynamic adaptation to changing environmental conditions. The result of this evolution in facade technology is the availability of high-performance products and materials [6]. An example of an innovative facade is the double-skin facade. According to Pomponi et al. [13], a double-skin facade is a hybrid system made up of the building's own facade, which constitutes the inner skin, and a glazed outer skin. The two layers are separated by an air cavity with fixed or controllable inlets and outlets. Unlike sealed buildings, the double-skin facades do not create a definitive barrier between the internal conditions of the building and the external environment. In order to reduce the energy demand of buildings and improve the aesthetic appearance, different types of double-skin facade have now been specified as a building envelope, as a change in the priorities by which modern buildings are constructed has taken place over the years. Nowadays, the creation of a sustainable working environment, with human comfort and energy efficiency, has been considered a high priority in construction and has gained emphasis and prominence [14] (Fig. 1).

A ventilated wall is a double-skin envelope, but differs in its construction and operating mode [14]. The main purpose of the double-skin facade is to utilise solar radiation during the season when the building needs heating [15]. The outer layer of the double-skin facade is generally made up of transparent elements and there are ventilation openings in the outer layer and inner wall; in this way, external air is circulated by opening air into the interior of the building [14]. In the case of ventilated facades, the main objective is to dissipate the heat generated by solar heating by means of the stack effect in the cavity [15]. They are opaque; only the outer layer has openings. Therefore, external air circulation is achieved through the air space between the outer layer and the inner wall [14]. Fig. 2 shows a picture of a building containing a ventilated facade with porcelain tiles.

Shopping JK Iguatemi, São Paulo, SP – Brazil. Building characterized by the use of a ventilated facade with porcelain tiles.

Source: Eliane [16].

Architecture, as well as the construction sector, has shown a special interest in ventilated facades in recent years [2,5,17]. The use of the ventilated facade system (VFS) offers a variety of external claddings and the possibility of selecting a wide range of materials, colours and cladding sizes [2]. They are based on a special type of envelope, where a second layer (or skin) is placed in front of a normal building façade [17]. Improvements to building envelope layers have a high potential to increase the energy performance of the building, especially in summer [17,18] and can improve the acoustic characteristics and day lighting inside the building [17]. The performance of the building envelope must guarantee thermal comfort in internal environments, as well as limiting energy consumption and waste, satisfying environmental and technological requirements [15].

Currently, it is possible to identify a notable number of studies and articles related to “ventilated envelopes”, mainly centred on investigating the main characteristics that affect the building's energy performance [2,19]. There are several studies related to the double-skin facade, photovoltaic integrated building, solar chimney and facade solar collectors [2,5,20–24]. In some cases, VFS is combined with building-integrated photovoltaic panels or thermal collectors [25].

Studies on VFS are limited [2,5], including reviews on the subject. For example, the review by Ibañez-Puy et al. [2] included information from different studies carried out that address the thermal and energy performance of VFS in recent years, while the review by De Gracia et al. [17] covered an overview of different types of numerical modelling to describe the thermal response of VFS. However, VFS has evolved greatly in recent years.

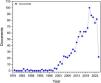

Therefore, this review, carried out from 2002 to 2024, aims to provide a comprehensive set of information on VFS for architects, engineers and researchers, bringing together the various definitions of the system over time, addressing historical aspects related to the evolution of the system, the various existing typologies, the classification and description of the system, the efficiencies and deficiencies and the architectural aspects, emphasising the thermal performance and innovations of the system.

DefinitionsThe use of ventilated structures in buildings has been a widely used solution in contemporary architecture.

According to Herzog, “it is meaningful to speak of the building envelope as a ‘skin’ and not just a ‘protection’, something that ‘breathes’, that reacts to the climate and environmental conditions between inside and outside, similar to humans” [26].

There are many definitions of the ventilated facade system. It came about with the aim of having an enveloping layer that combined the aesthetic point of view with an application of value [26].

The ventilated facade concept is derived from the curtain wall system, with an air chamber, which can have open or watertight joints [5]. Both systems are characterised by being a non-adhered system installed using metal inserts or a metal substructure with an air chamber [10,27]. What differentiates them is that, in the case of VFS, the air in this chamber is constantly renewed by an upward flow of air. Therefore, every ventilated facade is considered a curtain wall, but not the other way round.

Huang et al. [28] reported that a curtain wall is characterised by any building wall in any type of material that does not support superimposed vertical loads, i.e., an unsupported wall. The curtain wall provides aesthetic, environmental and structural functions in order to achieve the closure of the structure necessary for the safety, comfort and functionality of users. Due to technological developments in manufacturing and construction, over the years glass and steel panels have been produced at reduced cost for the construction of lightweight and aesthetically popular facades in modern buildings, especially tall and historic ones. Today, glass has become the most popular type of facade.

According to Boafo et al. [10], a curtain wall is a prefabricated facade, made up of glass and panels of various materials, which completely or partially surrounds a metal building structure, forming a barrier against the weather. The curtain walls are anchored to the slabs of the building, hanging like a curtain, are non-load-bearing and are designed to span several floors. The curtain wall system is a set of glass units, opaque panel units and connecting metal structures or joints. The curtain wall can have different appearances, but are characterised by being closely spaced vertical and horizontal uprights, i.e., metal structure overlaid with glass, metal or composite panels.

The ventilated facade is a double-skin facade, which is industrialised in the concept of a multi-layer composed of two opaque layers and a ventilation channel between them [5].

The new ventilation concepts of VFS are characterized as the so-called double-skin facades [29], which have appropriate openings on the external facade and regular windows on the facade bounded by the building. The installation of a second transparent facade at the front of the building with horizontal ventilation grilles makes it possible to reduce the effects of pressure fluctuations and facilitate natural ventilation.

According to Safer et al. [30], the double-skin facade is a special type of envelope in which a second skin, usually made of transparent glass, is placed in front of a regular building facade. The empty space in the middle is called a channel. This is ventilated naturally, mechanically or using a hybrid system, which is intended to reduce overheating problems in summer and contribute to energy savings in winter.

Ding et al. [31] stated that the double-skin facade is made up of an external facade, which is usually made of glass and offers weather protection and improved acoustic insulation against external noise, an intermediate space and an internal facade. The air in the intermediate space is heated by solar radiation. With openings in the facades, the air flow through the intermediate space is activated by the chimney effect.

There are many synonyms for ventilated facade, for example active facade, double envelope, rainscreen or double-skin facade (DSF) [25], also called smart facades due to their energy-saving potential [32].

The conventional double facade is effective at reducing heat demand, but has limitations when it comes to reducing cooling demand. Therefore, in order to improve overall energy performance, the double facade can be modified [33].

The VFS, which is a double-skin facade, can be combined with photovoltaic panels integrated into the construction and over the last 15 years has become a growing and important architectural element in buildings [9]. Vertical installation takes the form of a double-skin facade with photovoltaic panels facing south or west [34]. Combining photovoltaic systems with a double facade can reduce energy demand and can be called an integrated photovoltaic building. The possibility of adding a water system to the cavity of the double facade can absorb a potential amount of heat, achieving the goal of reducing cooling demand and maintaining thermal comfort [33].

The possibility of varying different types of glass in the composition of the double facade, such as low-emissivity (low-E), electrochromic (EC) and thermochromic (TC) glass, can be altered in order to improve the energy and thermal performance of double facades [33].

Ventilated facades can be called opaque ventilated facade (OVF). This is a type of facade that absorbs solar energy and transfers it to the ventilation system [35].

The term open joint ventilated facades (OJVF) can also be used [25]. The open joint ventilated facades are a special type of ventilated facade, double envelope, double skin, advanced integrated facade or lightweight facade. There is no general agreement on a proper name for these facade typologies [36]. The OJVF is a building system that is widely used as an element to protect against solar radiation, so it is important to characterise the natural phenomena of convection [37].

These facades are marked by localised discontinuities at the joints, which makes the flow much more complex, inhomogeneous and asymmetrical [38]. The outer layer is usually specified with ceramic material [39] or metal [40].

There are various definitions of the ventilated facade system available in the literature. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of each existing definition.

Main characteristics present in each definition of the ventilated facade system available in the literature.

| Work | Main characteristics |

|---|---|

| Agathokleous and Kalogirou [9] | Two parallel slabs separated by a gap with an upward air flow between them as double skin ventilated facades (DSVF). |

| De Masi et al. [41] | Typically made up of an external wall, on which a layer of insulation material is fixed, and a cladding system; between these an open-air chamber is created.The chimney effect determines the thermo-hygrometric behaviour of a ventilated facade. |

| For Sánchez et al. [25] | Ventilated facades with opaque cladding (OVF) can be represented by the use of a continuous insulation layer adjacent to the internal wall and a protective external layer, formed by a cladding mechanically fixed to the wall, creating a naturally ventilated duct.The term “ventilated facade” is more appropriate for opaque building elements. |

| Müller and Alarcon [27] | Characterised by the existence of ventilation in an air chamber, which causes the air to flow upwards due to its heating inside the chamber.Pressure differences inside the air chamber caused by the action of the wind also contribute to ventilation. |

| Suárez et al. [36] | The open-joint ventilated facade (OJVF) is a way of making the external closure; a metal structure is fixed to the masonry wall, which acts as a support.The external tiles (ceramic, metal, stone, etc.) are mounted on this structure, creating an air chamber between this layer and the main wall.The small gaps left between the tiles are called “open joints” that allow the facade to be ventilated effectively. |

| Giancola et al. [38] | Ventilated facades use a system generally made up of a continuous insulating layer applied to the wall of the building, while another layer is fixed to the building using mechanical fixing systems.There is a naturally ventilated chamber between the two layers. |

| Balocco [42] | Multifunctional thermodynamic system used to associate the external characteristics of the facade with the passive behaviour of the building.The air duct can be independent or integrated with other systems.These systems can be heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC). |

| Gratia and de Herde [43] | There is a pressure difference in double facades.The air chamber is in contact with the outside air through openings at the top and bottom, so that pressure equalisation takes place.The colder and denser outside air forces its way into the air chamber, raising the pressure at the bottom and causing the air to rise through the chamber and be expelled at the top. |

| Patania et al. [44] | Consists of an external cladding with a structure attached to the wall of the building, an insulating material and a metal structure that supports the cladding and the insulating material.The air flow, due to the pressure difference inside the ventilated duct, transfers heat by natural convection. |

| Gonçalves and Lopes [45] | Characterised by the existence of an aluminium or stainless-steel structure, fixed to the building's sealing wall at an average distance of between 10 and 15cm.The facade's finishing material (ceramic tiles or glass) is applied over this structure, forming a complete second skin on the building.This structural design creates an air chamber between the building wall and the facade cladding. |

| Stazi et al. [46] | External cladding system fixed to the building using mechanical fixing points.There are four functional layers: the external cladding, the ventilation chamber, the continuous insulating layer and the internal wall. |

| Rahiminejad and Khovalyg [47] | Three main layers that make up the ventilated wall: a wall close to the inside of the building, a cladding exposed to the open air and an air chamber formed between the two walls.The ventilated air chamber has two openings, an inlet and an outlet, to allow air to flow from the bottom to the top. |

Thus, considering the different point of view showed in Table 1, a ventilated facade system may be considered to be an aesthetical double parallel wall enclosing a chamber that, due to a pressure difference between the exterior and interior of the chamber, promotes an upward air flow to promote thermal and acoustic insulation of the building.

Brief historyVFS is a multi-layer cladding system originally developed in northern European countries [2,26]. As mentioned before, VFS is a system derived from the curtain wall. The curtain wall facades have been adopted all over the world as a characteristic sign of modern architecture [10]. The first fully glazed curtain wall structure dates from 1851. The Crystal Palace in London was designed by Sir Joseph Paxton. The building was an enormous glass and iron exhibition hall [10]. It consisted of a complex network of iron bars supporting transparent glass walls. The main body of the building was 563m long and 124m wide; the height of the central transept was 33m, with a total area of around 92,000m2[48]. The introduction of this architectural typology was prompted by the need to reduce the wall's footprint, construction time and the weight of the structure; this results in material and transport savings, structural flexibility, improved natural lighting, architectural layout flexibility and structural economy and independence [10].

However, curtain wall facades are examples of unventilated double-skin constructions. In 1849, Jean-Baptiste Jobard, director of the Brussels Industrial Museum, described the earliest citation of a mechanically ventilated multi-skin facade. He stated that the winter warm air should circulate between two panes of glass, while in summer the air should be cool [49].

Another early example of a double-skin facade was made by the American botanist Edward Morse. He developed what could be the first working multiple walls. His observations of the heating process of dark curtains led him to build a solar wall in 1882 [50].

The first double-skin facade installed in a real building was seen in Giengen, Germany in 1903 [51,52]. Richard Steiff designed a toy factory for his father [50], with an architectural typology that allows external ventilation of the cavity, thus being considered one of the first examples of a naturally ventilated multi-skin façade [49]. The double skin was installed taking into account the strong winds and cold climate of the region and the intention to maximise natural daylight [51]. The architectural typology adopted proved to be efficient and two extensions were built in 1904 and 1908 using the same double-skin system [50]; however, for both extensions, there was a change in material. For the first building, steel was used for the structure and for the extensions, wood was used for budgetary reasons. All the buildings are still in use [53].

In 1904, the Post Office Savings Bank was built in Vienna, Austria [50]. The building was designed by Otto Wagner, winner of the Post Office Savings Bank competition. The building was constructed in two phases from 1904 to 1912 (the year of completion) and has a double-skinned skylight in the bank's main hall [53], which is still in use by the same owner [50].

The great modernist architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Le Corbusier, put a lot of effort into projects of this type [50]. At the beginning of the 20th century, Le Corbusier used projects with double facades, such as Centrosoyus (1928) in Moscow, La Cité de Refuge (1929) and Immeuble Clarté (1930) in Paris [53]. The architect pointed to the ability of ventilated double facades to mediate in a controlled manner the variation of the external climate as the main benefit, calling it the Mur neutralizant concept [54], in which Le Corbusier claimed that heat transmission losses and gains would disappear through the circulation of air in the envelope cavity. The architect did not realise that the circulating air required energy to be heated or cooled. The idea was abandoned due to inefficiency and high costs. Le Corbusier carried out some experiments at the Saint Gobain glass company [49].

The double-skin facade was introduced in the early 1900s, but little progress was made until the 1990s [55].

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, mechanically ventilated facades began to be implemented in buildings, mainly in Europe, as a reflection of the energy crises of 1973 and 1979. The main objective was to reduce losses in winter and minimise solar gains in summer. Energy efficiency and thermal comfort ceased to be a problem exclusive to Nordic countries with cold climates [49].

Giancola et al. [38] stated that natural ventilated walls have become an established technology, resulting from spontaneous architectural construction techniques, which involve the use of natural materials attached to wooden supports, which in turn are mechanically fixed to the building. The aim of this technique was mainly to use it to protect the external surface of the wall from rain.

In the 1990s, growing environmental concerns, both from a technical and political point of view, began to influence architectural design, making green buildings seen as a good image for corporate architecture [53].

In recent years, double-skin facades have become a growing architectural element [9]. This system is currently used in several countries, where companies exploit this market and have the technology to implement the system.

In Brazil, this system is still not widespread; the first works using this system were carried out in 2000 [56], but the country has the technology to develop an appropriate VFS system for use in the country [27].

Thus, since the nineteen centuries in the northern European countries, VFS has been used as an aesthetic and thermal insulation solution for modern buildings around the world. However, its function has been meeting another application, as will be discussed in the following.

Typologies of the ventilated facade systemThe use of intelligent facades is a crucial criterion for the development of environmentally benign built environments [57].

The thermal, energy and acoustic performance of VFS depends on a number of specific external parameters [2]. Implications of external environmental conditions and design decisions, i.e. the properties of facade components and the building itself, directly influence facade performance [2,36]. It is important to customise facade design according to specific local climatic conditions. The facade should be designed to cope with situations with the lowest possible energy consumption. Commonly, the facade configuration should be designed considering the most unfavourable season [2].

Various types of VFS have been studied, according to different criteria in terms of:

- (i)

type and size of the channels;

- (ii)

factors linked to the site, such as solar radiation, wind direction, exposure and speed, temperature [2] and exposure [40], which determine the site's microclimate;

- (iii)

type of external cladding, such as the characteristics of the materials next to the channel and of the inner layer [25], the material of the external panel, the distribution and position of the openings, the radiating properties of the external panel; and

- (iv)

the size and shape of the space between the wall and the external panel [32]. In the case of low wind speeds (<0.5m/s), the greater the temperature gradient, the more cooling by the buoyancy-driven effect is achieved [2].

Climatic conditions do not change constantly. Therefore, an important simplification can be assumed. For summer, consider sunny days and high temperatures, and for winter, cloudy days and low temperatures [2].

In regions with high levels of solar radiation, VFS keeps the temperature of the internal layer of buildings at a temperature close to ambient, due to the significant reduction in the impact of incident radiation on the internal environment. When ventilated walls, facades and roofs are well designed, they can help to considerably reduce summer thermal loads due to direct solar radiation [58].

With regard to the design decision, consideration should be given to the material of the outer layer, the joints, the specific design (geometry), the materials [2], the width and height of the ventilation channel, the type of external cladding, the characteristics of the materials that are placed adjacent to the channel and the material of the inner layer [40], in addition to the geometry and thermal characteristics [36]. These parameters can be chosen according to each project [2].

Many parameters have an impact on the system's behaviour and the building's energy budget and can be divided into two main categories [46]:

- (a)

external boundary conditions. A ventilated facade is a type of facade that absorbs solar energy and transfers it to the ventilation system. Therefore, the ventilation load of the heating system can be reduced in winter [35]. The energy savings of this system depend heavily on climatic variables, such as the geographical location of the building and especially the solar radiation on the facade, the ambient temperature and the wind speed [35,46];

- (b)

design choices related to the dimensions (width and height of the ventilation gap), external cladding material and configuration of the joints, which can be open or closed [46]. In the case of a continuous external panel or with closed joints between the panels, ventilation is possible due to the openings at the bottom and top of the air chamber. When the joints are open, they allow outside air to enter and exit the cavity along the wall. In these cases, the joints deal with various expansions caused by temperature changes [5].

Regarding the external panel, facades can be divided into three groups: sealed cavity facade, facade with closed joints and with open grilles (at the top and bottom) and facade with open joints and open grilles [32]. Sealed cavity facades are those in which the air cavity and the outside air are not connected. Closed-joint facades with open grilles are those in which the cavity is in contact with the outside air and there is air flow through the cavity. Facades with open joints and open grilles represent the most common construction. The model with closed joints and open grilles is simpler than the model with open joints and grilles and can therefore be used to describe both situations [58].

There are two types of external cladding on ventilated facades: continuous, with closed joints, or discontinuous, with open joints [38]. In continuous or closed-joint ventilated facades, the upward flow is continuous, homogeneous and symmetrical along the wall [2,38,44]. In open-joint ventilated facades, the flow is discontinuous and is marked by discontinuities located at the joints, making the flow complex, inhomogeneous and asymmetrical [2,21,38]. This type of facade allows external air to enter and leave the cavity along the wall. Apart from aesthetic and constructive reasons, the main interest in open-joint ventilated facades is their ability to reduce thermal cooling loads. This occurs through the buoyancy effect induced by solar radiation inside the ventilated cavity, where air enters and exits freely through the joints [21].

The outer panels are separated by horizontal and vertical joints in order to resolve expansions caused by temperature changes. This effect is the result of solar radiation and the resulting convection inside the cavity. The flow of rising air creates a ventilation effect that helps to remove heat from the facade (Giancola et al. [38]). Open joints influence air velocity. The higher the air velocity in the ventilated facade, the greater the cooling effect [2]. Therefore, to minimise heat loss during the winter, smaller openings should be chosen. If the aim is to increase the ventilation rate to prevent overheating, it is advisable to use larger openings. The cooling effect also increases with height [41].

The configuration of the joints (geometric factors) in the external skin of the ventilated facade, with the presence of ventilation joints, which can be open or closed, influences the performance of the VFS [41,59]. There is a consensus that larger and larger joint openings help to reduce heat loss in winter and prevent overheating in summer [60].

The internal wall, with basic thermal insulation and watertightness properties, is mostly made of solid materials, such as concrete or masonry, and covered with insulating materials [60].

Among the types of double-skin facade, there is a simple and interesting alternative for utilising solar radiation in a building. Both solid layers are opaque. The outer layer is used to absorb solar energy and transfer some of it to the air in the gap. The inner layer acts as an insulation layer, avoiding the risk of overheating in the summer, while some of the solar energy can be used to heat the ventilation air in the winter. These are the opaque ventilated facades (OVF) [35].

Sánchez et al. [25] analysed the influence of the characteristics of the materials adjacent to the channel and the material of the inner layer.

So, the several different existing types of VFS are a resulting of the external parameters (temperature, air velocity, among many others), climate conditions (solar radiation level, unexpected climatic events, for example), design characteristics (aesthetic, kind of materials, geometric factors, for example), among others, that cause a direct impact in the thermal and acoustic performance of the building.

Classifications of ventilated facadesWhen it comes to ventilated facades, there is no agreement on their proper name. This type of building facade solution can be categorised according to different criteria. According to Suárez et al. [36], the International Energy Agency classifies advanced integrated facades according to the type of ventilation, the air path and the configuration of the facade, mainly related to the materials used. Some of the characteristics analysed are the properties of the facade components and the building itself, such as geometric, physical, thermal and optical properties, energy performance and control optimisation.

It is common knowledge that the main benefit of VFS is heat dissipation. This feature arises from the outer cladding absorbing the incident solar radiation and the ventilation conducted by natural convection in the ventilated cavity. The inner layer of the system acts as an insulator for the building. There is also a conducted buoyancy effect in the ventilated cavity, which pushes hot air out of the system, allowing cold air to enter the interior [61]. Fig. 3 shows the entry of cold air and the exit of hot air through the ventilated air chamber, the so-called chimney effect.

The differences between the densities of the outside and inside air, caused by different temperatures and humidity levels, cause thrust forces to occur. The removal of hot air from the facade also occurs due to the forces exerted by the wind [61,62].

According to Pujadas-Gispert et al. [61], the characteristics reported among the functions of ventilated facades are: the external facade will absorb the incident solar radiation, the heat will be distributed by convection in the ventilated cavities and air fluctuations will be generated between the slabs and the external cladding due to the temperature difference, which will push the hot air out and allow cooler air to enter, providing a natural upward air current through the ventilated layer.

There is a high level of congruence between the characteristics of building envelope layers and the visual, acoustic and thermal comfort of interior spaces [57].

Thus, the classification of VFS includes the type of ventilation, the air path and the configuration of the facade, aimed to heat dissipation. The type of the used materials assumes an important role in this classification beyond the properties of the building itself (thermal property and energy performance, for example).

Descriptions of the ventilated facade systemWhen it comes to the compositional elements, the VFS generally consists of a rear wall, also called the inner panel, on which a layer of insulating material is placed, and a cladding system that creates an open-air gap, also called a ventilated air chamber between the insulated wall and the outside environment [41,44], as shown in Fig. 4.

The interior panel, also called the supporting wall, is a confined masonry wall supported by the building's load-bearing structure. It serves as the base for the system's metal substructure. The inner panel is generally made up of solid materials such as bricks and concrete and covered with insulating materials [63]. The inner layer acts as building insulation [2].

The thermal insulation is a continuous layer over the entire height of the support. Closed pore insulation such as polyurethane foam is usually used, but open pore insulation such as mineral wool, expanded polystyrene (EPS) and extruded polystyrene (XPS) can be used [63].

The ventilated air chamber acts as a thermal buffer. It reduces heat loss during cold days, unwanted heat gain during hot days and thermal discomfort caused by asymmetrical thermal radiation [64]. Its main function is to remove excess heat and humidity accumulated in the chamber by convection and to prevent rainwater from passing into the building, draining off what can infiltrate. The behaviour of the ventilation channel can vary depending on the reciprocal positions of the thermal insulation and the inertial mass [40]. The purpose of this cavity, which is created between the internal and external environments, is to positively exploit natural ventilation, solar radiation and thermal insulation [15].

The “chimney effect” that occurs in the air chamber is excellent during the summer, saving energy and solving durability problems due to atmospheric agents and aggressive solar radiation [39,65]. This effect is also effective in winter [39,66]. The ventilated air cavity increases the transfer of heat and humidity between the internal and external parts, and helps to make the building envelope more efficient [63].

In the air chamber there is continuous ventilation in the vertical direction. The intensity of the chimney effect depends on the temperature difference between the internal and external air and the height of the internal air column [43]. The cavity must be designed in such a way as to reduce pressure losses along the channel [41]. It is possible to achieve a sensible heat cooling effect due to solar radiation when the width of the chimney air cavity is greater than 7cm [42], but the average thickness is typically 10–15cm [2]. Energy savings tend to increase as the width of the air duct increases up to a maximum of 15cm [66], although acceptable performances can be achieved with air cavity widths between 10 and 24cm [59]. It is important to emphasise that an increase in the width of the ventilated air chamber leads to an increase in construction complexity, resulting in high costs related to the execution of the work [2]. The work of Lin, Song and Chu [60] showed that the width of the chamber is a characteristic that significantly affects performance in winter, but this is not the case in summer. The 20cm wide chamber provided the most robust airflow rate for the open-joint ventilated facade in summer, leading to a considerable reduction in thermal load, especially with intensive solar radiation. In winter, the chamber offered the best and most reliable insulation performance for a closed-joint facade without air vents.

The height of the chamber is an important parameter for convective thermal performance [8]. The cooling effect increases with the height of the chamber in relation to ground level [39]. Higher chamber heights are recommended in order to increase the drive pressure difference for ventilation [8]. Air temperature differences in ventilated air chambers of greater heights are considerably greater, favouring air flow [39]. Facades at lower heights receive a greater share of the radiation reflected from the ground and are less influenced by the action of the wind [40,41]. According to Zöllner, Winter and Viskanta [29], in built-up buildings, the gap distance between the transparent facade varies from 0.3 to 1.5m and considering a typical storey height of around 4m, this results in a box window height/internal facade distance ratio, H/S, of between around 3 and 15.

The fixing system consists of vertical aluminium profiles and stainless-steel metal inserts. The external cladding or outer panel is made up of large-format modular panels in various types of material. It defines the external image of the building while configuring the ventilated air chamber. The joints in these plates can remain open and allow outside air to enter and leave the cavity along the entire wall, as well as combating expansions caused by temperature changes [2]. In some applications, the joints between the plates are closed or the outer skin is continuous. For these cases, ventilation occurs due to openings at the bottom and top of the cladding [2]. According to Lin, Song and Chu [60], the factor that most interferes with performance in summer and winter is the opening rate of the surface joint. This is due to the way in which the joint opening ratio of the outer skin affects the ventilation mechanism of the air chamber and the solar irradiation reaching the inner wall surface. In terms of thermal performance, these factors have opposite impacts. In summer, the increase in joint openings will allow outside air to enter and leave the chamber along the entire wall in order to dissipate the accumulated heat; however, the increase in unwanted solar heat also reaches the inner wall through the openings. In winter, the ventilation/irradiation relationship is also present, but it behaves in the opposite way. The intensity of solar heat reaches the surface of the wall through the openings, but is eliminated due to the chamber's improved ventilation.

When it comes to the external panel material, low thermal conductivity (k), high density (ρ) and high specific heat values (cp) are recommended [41,44].

The (external) finish colour has a significant impact on the heat transfer rates of a VFS in summer. The adoption of materials with low solar radiation absorption coefficients is recommended [60]. According to Lin, Song and Chu [60], in summer, the impact of the colour of the external cladding is the second most significant factor, second only to the rate of joint opening. Light colours applied to external cladding can reduce daytime heat gain while increasing the night-time cooling effect in summer, lowering daily heat transfer rates compared to dark colours.

In summary, it is clear that the chimney effect is the main phenomena related to the air flow that causes the thermal insulation in the VFS. The temperature difference between the internal and external air and the height of the internal air assumes a critical role. Moreover, the drive pressure difference for ventilation is improved at higher chamber heights, favouring air flow and the maintenance of higher air temperature differences. Although there is no consensus among authors regarding the ideal dimensions of the cavity to obtain the best chimney effect, the width of the chimney air cavity can be considered to be typically between 10 and 15cm to guarantee the best energy savings.

Materials used as coveringsVFS has seen an expansion in use due to the possibility of hosting different types of cladding, allowing architects to explore a wide variety of facade combinations [19]. The materials used in building envelopes play an important role in terms of sustainability, taking into account the energy performance of the facade. Materials influence indoor thermal comfort; insulation is used for heating as well as cooling in order to save energy [67].

There are various types of materials used to make up the cladding of the ventilated facade system (Figs. 5–7). This classification will determine the system's fixing system.

Copa Star Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, RJ – Brazil. Ventilated facade composed of porcelain tiles.

Source: Eliane [16].

Ripagaina Park residential building, Pamplona, Navarra – Spain. Ventilated facade made of aluminum composite material.

Source: Alu-Stock Lontana Group [68].

Alquería Market in Dos Hermanas – Seville. Ventilated facade made of polymer concrete.

Source: Ulma [69].

The behaviour of the facade is different depending on the external cladding material used [32]. The outer layer acts mainly as a radiation filter [2]. The materials currently used in the construction industry consist of modular panels with a variety of cladding options, available in metal, ceramic or composite materials [2,5], precast concrete, glass or aluminium [58] and even stone, aluminium composite panels, phenolic boards, cementitious boards, extruded ceramics and wood [25]. Translucent glass, ceramic/porcelain materials, opaque metal or photovoltaic modules are the most common to be used [32]. The cladding can be made of a thin metal, such as zinc-titanium [40].

Facades with outer cladding in reflective materials, such as special steels and titanium alloys, greatly reduce the influence of solar radiation and should be considered as an alternative to ventilated facades [66].

The application of a thicker solid material is also present in VFS, such as brick, ceramics and cement, and can be permeable or watertight [40].

Ceramic materials are reinforced with a composite consisting of a fibreglass mesh and polymer resin adhered to the ceramic plate. The combination of these components aims to guarantee the safety of the material after installation, preventing the release of fragments of the ceramic material in the event of a fracture of the ceramic coating [56].

The selection of materials to be applied in VFS can significantly reduce the environmental impact of buildings (Pujadas-Gispert et al. [61]). Considering the concept of sustainability and versatility, bio-based materials are being considered as promising resources for 21st century buildings and are highly valued [70]. Bio-based materials have a smaller environmental footprint than steel, glass and concrete. Bio-based materials can be produced on site in an environmentally friendly way and have low transport costs. They are renewable and reusable [61]. An example of this type of material is wood, which is a suitable material for the facade interface of the enveloping layer, such as the floors, walls and roof between the interior and exterior of the building, due to its low thermal conductivity [71]. However, these materials have some disadvantages, such as dimensional and thermal instability, low mechanical strength over time, low resistance to biotic and abiotic degradation processes and low fire resistance [61,70].

So, a large number of different types of cladding has allowing architects to design a wide variety of facade combinations, involving metallic materials as steel and aluminium, ceramic materials as precast concrete, glass, stone, porcelain, cementitious boards, extruded ceramics, polymeric materials, natural (as wood) or synthetic (phenolic boards), composite materials and, more recently, photovoltaic modules.

Fastening systemsThe VFS fixing system is made up of a metal substructure that allows the installation of cladding plates that are mechanically fixed.

The substructure can be made from aluminium [16]. The cladding is fixed with stainless steel screws. Four concealed fixing systems are used: metal inserts, stick, shackerley and clamp:

- •

Metal inserts: this system consists of vertical profiles and point metal inserts. The vertical profiles are installed using anchors, which are fixed to the base of the building with anchor bolts. The metal inserts have fixing pins, which are inserted into the cladding, as shown in Fig. 8;

Fig. 8.Detail of the fixing system with metal inserts – ELIANETEC.

Source: Eliane [16].

- •

Stick: this system consists of an auxiliary substructure made up of profiles, anchors and anchor bolts. The cladding is glued with structural sealant to a frame made up of aluminium profiles. The frame has clips that help it to be fixed to the structure, which is made up of profiles called columns and rafters, previously installed on the facade, as shown in Fig. 9;

Fig. 9.Detail of the Stick fixing system – ELIANETEC.

Source: Eliane [16].

- •

Shackerley: this system consists of anchors, horizontal and vertical profiles, and expansion bolts, which are inserted into the back of the cladding and anchor bolts, fixed to the base of the building, as shown in Fig. 10;

Fig. 10.Detail of the shackerley – ELIANETEC fixing system.

Source: Eliane [16].

- •

Clamp: the cladding is fixed using metal clamps, fitted into slots that are fixed into the cladding. The fasteners are not exposed on the surface of the cladding. The system consists of a substructure with vertical profiles, fixed by means of anchors at the base of the building, as shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.Detail of the ELIANETEC clamp fixing system. Fonte: Eliane [16].

As a visible system, staples are used. The fasteners remain exposed on the surface of the cladding. The cladding is fixed by means of metal clips without the need to make slots or holes in the cladding. The system consists of a substructure with vertical profiles, fixed by means of anchors to the base of the building.

Hilti [72] specifies aluminium framing systems. The solutions are quick and adaptable. The systems adapt to all types of panels. The systems include the anchoring system for fixing to concrete, the anchoring system for fixing to masonry and the screw fixing to concrete:

- •

Anchoring system for fixing in concrete: HRD plastic dowels are used in this application. However, whenever conditions are favourable, HUS3 screw anchors are used, which offer greater productivity and can withstand greater loads than traditional dowels;

- •

Anchoring system for fixing to masonry: this system is used for solid and perforated brickwork. HRD plastic dowels are the appropriate solution when the forces to be withstood are low. To withstand greater forces, the preference is for HIT-HY 270 and HIT-HY 170 injection chemicals, which are used with HIT-V threaded rods and HIT-SC modular perforated sleeves;

- •

Screw anchoring in concrete: screw anchoring is used to fix discontinuous coatings only in cases where the mechanical characteristics of the concrete are known.

Portobello [73] uses an aluminium composite structure, weighing approximately 3.5kg/m2, with screws coated with microceramic and polymer adhesive. The Lungo, Magna and Pendeo systems are used:

- •

Lungo system: this is the main system and is designed for standard-sized porcelain tiles. The porcelain tiles are suspended on horizontal profiles and fixed as if they were frames, allowing easy removal for access or maintenance, as shown in Fig. 12;

Fig. 12.Lungo system fixing detail.

Source: Portobello [73].

- •

Magna system: designed to fix thin porcelain tiles to an aluminium structure, withstanding wind pressure and allowing for expansion and movement. The adhesive used has a resistance of 21kg/cm2, as shown in Fig. 13;

Fig. 13.Detail of the Magna system fixing.

Source: Portobello [73].

- •

Pendeo system: designed for products in a specific line, the Lamina Line, which are 300cm×100cm slabs and 3.5mm thick. The porcelain tile is adhered to a support and reinforcement substructure and then installed on the aluminium structure. It was developed for large slabs, as shown in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.Fixing detail of the Pendeo system.

Source: Portobello [73].

Although different fixing systems can be found, a metal structure is typically the main support element of the VFS. Stainless steel screws are used to fix the cladding on this structure. The fixing system still uses metal inserts, stick, shackerley and clamp.

ETAG 034 [74] is a European standard that provides guidelines for the European technical assessment of ventilated facade building systems. This guideline covers kits for vertical external wall claddings consisting of an external cladding, mechanically attached to a structure, which is fixed to the external wall of buildings. These claddings are non-structural elements and do not contribute to the stability of the wall on which they are installed. These elements contribute to the durability of the works. The cladding kit consists of an external cladding and defined fixing devices. The cladding is mechanically fixed to the wall using a substructure. Walls are made of masonry (clay, concrete or stone), concrete (cast on site or as prefabricated panels), wood or metal structure. There is an air space between the cladding elements and the external wall. According to the regulations, the air ventilation space must be at least 20mm, which can be reduced locally to 5–10mm depending on the cladding and substructure, as long as it is checked that it does not affect the ventilation function.

The cladding elements are fixed to the external wall by means of a substructure, with wood or metal material (steel, stainless steel or aluminium). Cladding elements are made of wood panels, plastic, fibre-reinforced cement, concrete, metal, laminated panels, stone, ceramics, among other types. These cladding elements are usually assembled according to a detailed technical design, in accordance with the product's technical descriptions.

Through the mechanical design, the cladding is differentiated according to the fastening methods. The standard provides examples of possible materials to be used as cladding elements and fixings, which are referred to as families. The standard presents eight families (A to H) of cladding kits. Other cladding kits can be evaluated based on a similar analysis of these families. Figs. 15–22 were taken from the ETAG 034 standard and illustrate the fixing method for the main families of cladding elements and fixings.

Cladding kit mechanically fixed to the substructure using nails, screws, rivets, among others.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding kit mechanically fastened to the substructure, whereby the fastening is made by means of an undercut hole and anchored by mechanical interlocking.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding kit with cladding elements fixed to a horizontal grid of metal rails, bolted to a vertical substructure.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding kit with cladding elements, integrated into the adjacent elements by means of interlocking at the top and bottom, fixed to the substructure by mechanical fixings positioned on the upper edge and masked by the edge of the upper elements.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding kit with cladding elements fixed to the substructure by means of mechanical fixings positioned on the upper edge and masked by the upper edge.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding kit with cladding elements mechanically fixed to the substructure by 4 clips (minimum) or metal rails.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Cladding made up of elements suspended from the substructure.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

Suspended cladding kit.

Source: ETAG 034 [74].

The word facade is derived from French and literally means “front” or “face” [1].

Building facades are classified into two categories: glazed facades and opaque facades. Glazed facades are made of transparent or translucent materials, such as glass. Opaque facades are made of solid layers, such as masonry, concrete and stone [67].

The facade of a building is the most visible element and defines the aesthetic appearance, the identity of the building and its architectural expressions. It serves as a physical barrier and an interface between inside and outside and is constantly exposed to meteorological variations, which directly and indirectly affect users’ indoor comfort conditions, such as solar radiation, wind action and large temperature differences [75].

The facade has the ability to function as a protective element or regulator against the strong fluctuations of the external climate [76].

The facade, which is the main component of the building's envelope and which limits the external and internal environments, has an impact on the environmental conditions of internal spaces, on the thermal performance of buildings and, subsequently, on user satisfaction [57]. According to Mirrahimi et al. [77], when drawing up a facade project, a series of parameters must be taken into account, such as the location (orientation and climatic conditions), the shape (width, length and height), the material of the external walls, roofs, glazed areas, natural ventilation, the thermal comfort required by the occupants and external shading. The facade is where some of the most significant heat exchanges between the building and the environment take place, which is why it is an important aspect of a good project aimed at improving a building's thermal performance [37].

Zero-energy building design has become a priority for architects and researchers related to architectural engineering and building physics [78]. In this way, architects and engineers must make important decisions at an early stage of building design, with a view to the final impacts of the construction on the overall energy performance and internal comfort conditions of the buildings [67].

For architecture and engineering, the facade of a building is divided into two parts. The solid part refers to the stable and opaque structural elements, such as solid walls, while the void part refers to the light and transparent structural elements, such as glass, windows and doors. The harmony of these parts can give different appearances to a building [1], as well as being associated with the comfort and well-being of users inside the building. Solid and empty parts need different treatments for sound penetration, lighting, sunlight, air flow and visual penetration for users [1].

Some parameters should be associated with the process of developing a building's facade design [75]:

- •

Control of solar utilisation: the comfort level of users is associated with the solar radiation allowed into the building, which directly influences the internal temperature of the building;

- •

Natural ventilation: the building skin can control the natural exchange and circulation of air in order to minimise the use of heating and air-conditioning systems;

- •

Natural vs artificial lighting: a suitable combination of natural and artificial light is the main objective for minimising energy consumption. The entry of natural light into the space, through the opening of windows and doors in the walls of a building, and shading systems are the main components of any envelope, as they influence internal lighting and the well-being of the user. The challenge is to let daylight in as deeply as possible, reducing overall energy consumption and keeping the individual visual sensation comfortable;

- •

View to the outside: through openings in the walls, there is a psychological visual connection between users and the outside;

- •

Heat control: a building's thermal performance is directly associated with controlling the flow of heat between the interior and exterior;

- •

Moisture control: the building's skin deals with two types of moisture, rainwater and condensation. Rain exposes the facade to external humidity and condensation is formed on cold surfaces inside the room when there is a sudden temperature oscillation between the inside and outside of the building room due to insufficient envelope insulation;

- •

Noise: acoustic insulation is a fundamental factor in the performance of a facade, as it is subject to external noise.

Facades are fundamental elements for internal lighting, internal thermal environments and the utilisation and control of solar energy [1]. Contemporary architecture is not limited to the use of materials or surface finishes, but results in a wide variety of materials and their articulations [4].

Today, bioclimatic architecture has become one of the most promising alternatives for reducing energy consumption in buildings and, consequently, reducing the environmental damage that fossil fuels are causing worldwide [79]. Sustainable development requires the creation of innovative facades. The sun provides abundant energy to the earth and it is essential to consider the impact of sunlight on facades and whether it should be reflected, absorbed or reused [1].

Smart facades, as an innovative integrated component of the building envelope, have been developed to correct all the disadvantages of current facades [57]. They are seen as a multiple functional element to reconcile conflicting needs such as heating, cooling, ventilation and lighting [80]. Among the types of intelligent facades are double facades, double-glazed facades, ventilated facades, kinetic facades and solar facades [57]. Curtain walls have also become a popular type of facade. In countries such as China, for example, the curtain facade is architecturally designed by the architect who is not normally involved in the structural design [28].

The design of ventilated facades is not a new topic; however, in recent years, the implementation of ventilated facades in buildings has been the subject of widespread application, especially when low energy consumption has become a priority in building design. VFS attracts architects and engineers for aesthetic reasons, its performance in sound insulation and also for improving the indoor environment [58].

Solar heating and cooling technologies can be driven by solar thermal energy. Solar thermal heating technologies use passive or active solar energy to collect solar radiation and transform the energy into usable heat. Passive refers to the design of the building envelope [20].

The need for energy conservation and sustainable design in buildings is causing new interest in passive solar systems [55,81]. A passive building is one in which the internal environment is regulated not by the operation of mechanical heating and cooling systems, but by the structure and architectural design of the building and its components [55].

According to Marinosci et al. [59], the architect and/or engineer must optimise the natural contribution of heat transfer within the cavity in order to achieve favourable performances from the ventilated walls; the temperature difference between the air and the walls induced by solar radiation and the forced convection component is associated with the wind that pushes external air into the cavity via the grilles at the bottom of the cavity. In order to increase air flow through the cavity, pressure losses along the cavity must be reduced. This can be achieved by eliminating the ventilation grilles at the ends of the cavity and avoiding the low thickness of the cavity. The radiative contribution of long waves (e.g., infrared radiation) inside the cavity must be minimised.

Among the passive solutions, the double-skin facade is attractive and promising [55,81]. The ventilated facade is a double-skin facade and its main architectural feature is its transparency, allowing contact with the building's surroundings and the fact that it lets in a lot of light during the day. The attractive aesthetic value is much sought after by architects, builders and owners [7].

Thus, the design of a VFS currently involves engineering and architectural elements to attempt much more than thermal comfort, such as control of the solar radiation, natural ventilation, a suitable combination of natural and artificial light, view to the outside and acoustic insulation. Such elements promote technical, economic and aesthetic gains.

Technical standardsThe purpose of technical standards is to experimentally evaluate facades, as well as to conceptualise and define guidelines for designing the system, among other relevant aspects. Table 2 summarizes the description of the main technical standards.

Description of the main technical standards applied to the ventilated facade systems.

| Standard | Description |

|---|---|

| ASTM E 631-93a [83] | It defines the curtain facade as a “non-adhered exterior wall that is securely supported by structural members of the building”. |

| ASTM E 283 standard [84] | It describes the test method applicable to external windows, curtain walls and doors to measure only the leakage associated with the assembly and not the installation.During the tests, temperature and humidity throughout the specimen must be kept constant; the rate of air leakage through external windows, curtain walls and doors should be under specified pressure differences in the specimen. |

| ASTM E 330 [85] | It determines the standard test method for structural performance of external windows, doors, skylights and curtain walls by uniformly distributed static air pressure difference using a test chamber.This test method is applicable to curtain wall assemblies including, but not limited to, metal, glass, masonry and stone components. |

| ASTM E 331 [86] | It deals with the assessment of water pressure resistance.This standard determines the standard test method for water penetration of exterior windows, skylights, doors and curtain walls by uniform static air pressure difference.Water is applied to the outer face and exposed edges simultaneously with a uniform static air pressure on the outer face greater than the pressure on the inner face. |

| EN 13830:2015 [87] | It specifies the requirements of curtain wall kit intended for use as a building envelope to provide weather resistance, safety in use and energy saving and heat retention and provides test methods, assessment, calculation and conformity criteria of the related performances.It specifies procedures for a facade performance classification by means of experimental tests. The main test procedure includes air permeability, airtightness, serviceability/wind load resistance, air permeability, water vapour permeability, thermal transmittance and airborne sound insulation. |

| ETAG 034 [74] | ETAG documents are issued and applied when standards do not cover specific areas.ETAG 034 puts in place performance requirements and test and assessment methods for cladding systems, corresponding to the areas of mechanical strength and stability, fire safety, hygiene, health and the environment, safety in use, noise protection, energy saving and heat retention, durability aspects and ease of service.It is divided into two parts [88]:(1) Part 1: Ventilated cladding kits comprising cladding components and associated fixings; and(2) Part 2: Cladding kits comprising cladding components, associated fixings, substructure and possible insulation layer. |

| UNI 11018:2003 [89] | It defines that the ventilated facade is a type of advanced barrier facade (“Facciate a Schermo Avanzato”). It is an opaque facade wall in which the external cladding is made up of various materials or shapes and dry-mounted.The ventilated facade is designed so that the air present in the chamber can flow out via a chimney effect, either naturally or artificially.However, this standard does not address the issue of mechanical degradation over time [90]. |

| DIN 18516-1 [91] | It applies to ventilated external wall cladding with and without substructure, including fasteners, connections and anchors. It defines planning, design and execution principles for permanent constructions.It establishes considerations in relation to design, acting loads, volumetric variations, the execution of the ventilated facade system and the carrying out of tests.The requirements for the design and execution of a ventilated facade system with natural stone slabs or concrete slabs are laid down in DIN 18516-3 [92] and DIN 18516-5 [93]. |

| DIN 18516-3 [92] | It stablishes the requirements and design of external wall cladding and ventilated for natural stone.In conjunction with DIN 18516-1, it regulates the use of natural stone slabs with nominal thicknesses ≥30mm for ventilated external wall cladding. |

| DIN 18516-5 [93] | It specifies the requirements and design for concrete block slabs, their fixing and anchoring, as well as calculation and design. In addition, specifications are made for joint formation. |

| ISO/TS 17870-3:2023 [94] | It provides guidelines for the installation of large-format porcelain tiles and panels by means of mechanical fixings to support structures, especially on ventilated facades. |

In Brazil, there are no specific standards or regulatory documents that specify the elements that make up the ventilated facade system, which define guidelines for designing, building and maintaining cladding systems; there is no performance assessment regarding safety, habitability, durability and maintenance [82].

Existing standardised approaches include the Brazilian standard ABNT NBR 10821-1 – Frames for buildings – Part 1: External and internal frames – Floor terminology [95], in which the curtain wall facade system is defined as being interconnected and structured frames, with a sealing function, that form a continuous system, developing in the direction of the height and/or width of the building facade, without interruption, for at least two floors. ABNT NBR 10821-2 – Frames for buildings – Part 2: External frames – Requirements and classification [96] specifies the performance requirements for frames for buildings, regardless of the type of material. This standard provides some requirements and assessment methods for structural performance (wind loads) and durability that can be adopted for ventilated cladding systems [27].

Thus, considering the complexity of the ventilated facade systems, for example the used materials and the configurations, the technical standards cannot cover all the relevant aspects related to the performance of the facades as acoustic insulation.

Advantages and disadvantagesCurrently, the civil construction sector is concerned about energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [97]. It is, directly or indirectly, the first pillar for the application of technologies aimed at reducing energy waste [15]. VFS is a type of facade system that offers sustainability benefits, the main reason for its popularity being the ease and speed of installation, the rehabilitation of buildings, making it a highly competitive system [98].

According to the literature, VFS present the following advantages compared to conventional facades:

- •

ability to reduce heat transfer through the building envelope in summer conditions, as well as preventing the risk of condensation and infiltration in winter caused by wind and rain, thus increasing the durability of the façade [19];

- •

building's energy performance, as well as internal comfort and the quality of the internal environment [5,18,36,57,60,63,99]. Besides, poor performance of building materials as an insulation layer can be corrected by the use of VFS [63];

- •

aesthetic purposes, guiding the envelope design process [19,60]. This system has become popular with architects because almost any colour and shape can be adopted [21,57];

- •

easier maintenance. The incidence of pathologies on conventional cladding facades often necessitates industrialised element alternatives such as VFSs, which feature a dry construction method that is simple, fast and easy to build; this makes them competitive [5,21], due to their simplicity in implementation (Diallo et al. [100]);

- •

flexibility and adaptability can be cited as significant attributes for this type of facade, which can be customised to any preferred shape and colour (Ghaffarianhoseini [57]);

- •

retrofitting of old buildings. This system offers aesthetic improvements to buildings, both new and refurbished [21,36], and is widely used in the renovation of buildings, in the absence of rules relating to historical-architectural preservation [21,66];

- •

reduction of moisture problems within the building envelope by ventilation: rain penetration, frost damage, decay, corrosion, mould growth and discolouration of building materials [5,21,57,60,63,97,99], particularly with regard to the modernization of old buildings [47];

- •

minimisation of construction-related problems due to its industrialised components and better assembly control [2];

- •

acoustic performance can be improved by VFS [43,63], since the air cavity acts as additional acoustic insulation;

- •

ventilated structures can also be extremely useful for installing photovoltaic panels in order to increase their cooling and, consequently, their thermal efficiency [58].

Among the difficulties in implementing the ventilated facade system, the high price and investment cost are considerably higher than those of a traditional simple façade [7]. Besides, VFS need [45,101]:

- •

qualified and trained labour;

- •

specifications for installation, i.e., the need for a specific detailed project;

- •

specific accessories;

- •

changes in management and production processes.

Moreover, assessing the performance of ventilated facades is difficult due to the lack of software tools capable of fully evaluating the thermal performance of opaque ventilated facades [101]. There is typically a lack of data on the thermal and energy behaviour of the ventilated facade, specifically a lack of data on the envelope temperature. However, for existing buildings, the performance of a ventilated facade can be assessed using on-site measurements [61].

Thus, as can be seen in the literature, there are many advantages to using ventilated facade systems; however, there are also a series of challenges to be overcome, such as the high installation cost.

Thermal performanceClimate comfort is the most important biological requirement of human beings. Conditions are defined as those in which more than 80% of users feel satisfied. Thus, in order to guarantee the continued health and productivity of users, climatic comfort conditions must be provided in a building [102]. Nowadays, people spend most of their time indoors, such as homes, offices, schools, factories and shopping centres. Numerous studies have been carried out by researchers and architects in order to establish design guidelines with the aim of idealising indoor environments that meet indoor environmental quality requirements [57].

It is well known that energy consumption is a concern all over the world and the civil construction sector is one of the biggest contributors to this consumption [18] and the emission of greenhouse gases [103]. The main elements with the highest energy consumption in buildings are heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems, as they are the internal climate controls that regulate humidity and temperature in order to provide thermal comfort and indoor air quality [20].

The International Energy Agency indicates that residential and commercial buildings are responsible for around 32% of global energy consumption and almost 10% of CO2 emissions related to energy consumption [5]. The building sector is responsible for almost 40% of total CO2 energy-related emissions and 36% of final energy use worldwide [61].

In line with global policies, buildings have significant potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions [57]. Indoor heating is the main energy demand of buildings in cold countries and air conditioning is one of the main contributors to peak electricity demand in countries where the climate is hot [20]. In Brazil, buildings consume 50% of the electricity used in the country [104].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in sustainable building envelopes in order to reduce the impact of building development on the environment [52]. Interest in the use of sustainability systems is therefore widespread. The building envelope directly influences the annual energy consumption and, consequently, the operating costs for heating, cooling and humidity control of internal spaces [62]. Thus, these systems cover energy consumption factors, life cycle analysis and overall building performance [57].

The building envelope separates the internal space from the external environment, changing the amount of heat flow through itself [102]. In the case of the ventilated facade system with open joints, solar radiation on the outer cladding heats it up and activates convection inside the air chamber, generating ventilation as an upward air current that enters and leaves the cavity through the open joints. When this current leaves the chamber through the upper openings, it removes thermal energy. In this way, the temperature of the masonry wall and the flow of heat into the building are reduced, reducing the energy needed for air conditioning [36]. Thus, the envelope is the basic determining factor of the internal climate and the demand for supplementary mechanical energy [102].

When it comes to thermal comfort inside buildings, heating systems must provide or collect and store solar heat and retain heat inside the building [62]. Conversely, cooling systems must provide cool air or protect the building from direct solar radiation and improve air ventilation [20]. Thus, they can help to reduce energy requirements for heating, ventilation and cooling, while maintaining adequate indoor temperature and humidity comfort [36].

The envelope has the greatest impact on the overall energy consumption of the building [2,102]. Advanced facades, involving double facade technologies, have attracted increasing attention due to their thermal insulation performance [105].

There are various types of envelopes designed to improve the thermal and energy performance of buildings [58]. Exterior building elements, such as facades, can function as passive solar energy systems and act as barriers between external and internal conditions.