Surface-functionalized magnetic iron oxide (F-Fe3O4) nanoparticles have attracted close attention from researchers in various fields due to their stable chemical properties, good magnetic responsiveness, and biocompatibility. At present, F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles are widely used in many fields, including interfacial separation, catalysis, biosensing, and medical nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. However, there are still cognitive blind spots regarding the application of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in different fields. Herein, first of all, the basic theories of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles were systematically discussed, including structural characteristics, magnetic behavior, preparation methods, and characterization techniques. Then, based on the fundamental theories, the applications of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in important fields (such as oil–water interface separation, photocatalysis, thermal catalysis and electrocatalysis, biosensing and medical magnetic resonance imaging) were systematically reviewed. Finally, the paper delves into the scientific challenges faced by F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in various application fields, thereby providing potential insights and directions for the further development of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. This review is helpful to deepen the understanding of the scientific issues faced by F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles and provides theoretical guidance for the development and application of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Additionally, this review provides the necessary engineering theoretical guidance to accelerate the large-scale commercial application of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles, which possess significant scientific value and profound social significance.

Las nanopartículas magnéticas de óxido de hierro funcionalizadas en superficie (F-Fe3O4) han atraído gran atención por parte de investigadores de diversos campos debido a sus propiedades químicas estables, buena respuesta magnética y biocompatibilidad. Actualmente, las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4 se utilizan ampliamente en múltiples áreas, incluyendo la separación en interfaces, catálisis, biosensores y resonancia magnética médica. Sin embargo, aún existen vacíos en el conocimiento sobre la aplicación de las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4 en diferentes campos. En este trabajo, en primer lugar, se discuten sistemáticamente las teorías básicas de las nanopartículas magnéticas de Fe3O4, incluyendo sus características estructurales, comportamiento magnético, métodos de preparación y técnicas de caracterización. Luego, con base en estas teorías fundamentales, se revisan sistemáticamente las aplicaciones de las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4 en campos importantes (como la separación en la interfaz aceite-agua, fotocatálisis, catálisis térmica y electrocatalítica, biosensores y resonancia magnética médica). Finalmente, el artículo profundiza en los desafíos científicos que enfrentan las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4 en sus diversas áreas de aplicación, proporcionando así perspectivas y direcciones potenciales para su desarrollo futuro. Esta revisión contribuye a profundizar el entendimiento de los retos científicos asociados a las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4 y ofrece una guía teórica para su desarrollo y aplicación. Además, proporciona la orientación teórica de ingeniería necesaria para acelerar la aplicación comercial a gran escala de las nanopartículas F-Fe3O4, las cuales poseen un valor científico significativo y una profunda relevancia social.

Magnetic nanoparticles exhibit surface effect of magnetic response under the influence of an external magnetic field. Common magnetic nanoparticles mainly include some elemental metals, such as chromium dioxide (CrO2), ferrite (CoFe2O4), iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni), as well as iron nitride (Fe4N) and iron oxide [1–3]. Thereinto, magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles not only exhibit the common advantages of magnetic nanoparticles, but also have characteristics such as small volume, large specific surface area, stable chemical properties, high catalytic activity, good magnetic responsiveness, good biocompatibility, and low biological toxicity [4]. In addition, the special surface effect and superparamagnetism of Fe3O4 enable it to have specific functions through appropriate surface modification, thereby achieving more thorough adsorption and separation under the action of an external magnetic field [5]. Therefore, surface functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (F-MNPs) have received widespread attention from researchers.

At present, functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles are widely used in engineering (interface separation and catalysis) and biomedical fields. For example, Zhou et al. [6] designed and successfully synthesized a novel kind of amphiphilic magnetic interface separation material (M-ANP) by grafting aliphatic alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether onto the surface of epoxy-functionalized magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. It performs well in breaking the stable water-in-asphaltene emulsions, achieving the demulsification efficiency of 90.0% within 2min without heating. Guo et al. [7] prepared Fe3O4/BiOCl by a simple hydrothermal method combining with hydrolysis precipitation process. It shows excellent photocatalytic properties for organic pollutants in aqueous systems. The photodegradation rate of rhodamine B (RhB) reaches 100% when the exposure time to visible light is 40min. Molaei et al. [8] synthesized Fe3O4@SiO2 superparamagnetic nanoparticles through the co-precipitation method. The synthesized nanohybrid exhibited 81% drug loading, and a 25% and 38% drug release within 48h at a pH of 7.4 and 5.5, respectively.

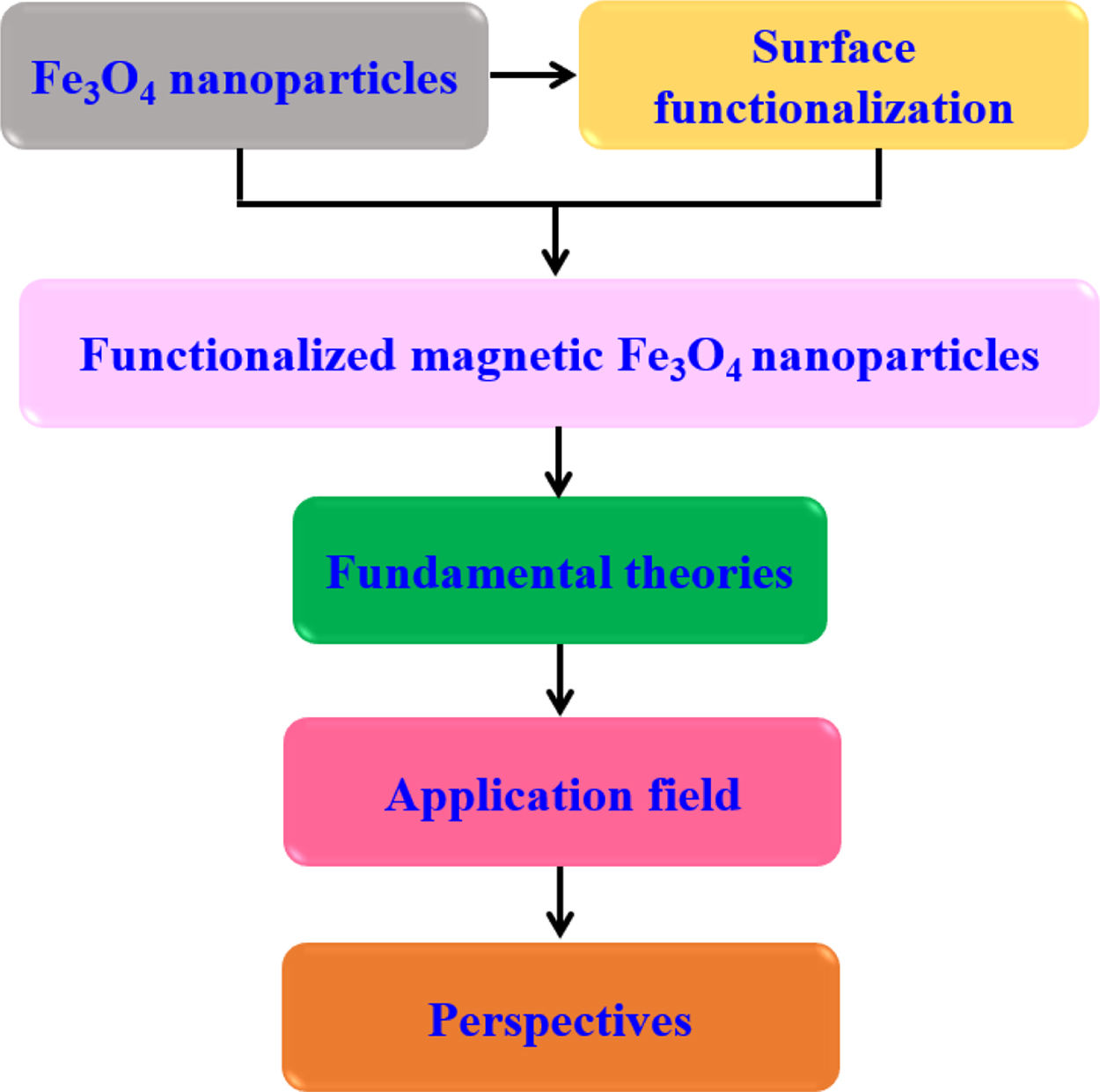

In summary, as shown in Fig. 1, firstly, the fundamental theories (the structural characteristics, preparation methods and surface functionalization of Fe3O4 nanoparticles) of F-MNPs are systematically discussed in this paper. Then, the application of F-MNPs in typical fields such as interface separation, catalysis, biosensors, and functional magnetic resonance imaging were systematically reviewed. Finally, the important opinions were expressed on the future development of F-MNPs. The important review will provide the necessary theoretical basis for further expanding the application scope of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, which possesses important scientific research value in the field of functional magnetic materials field.

Fundamental theoriesClarifying the fundamental theories of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles is a prerequisite for an in-depth understanding of its applications. Therefore, this section systematically elaborates on the basic theories of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and its surface functionalization.

Structural characteristics of Fe3O4 nanoparticlesMagnetic Fe3O4 is a spin-polarized mixed-valence metal with an inverse spinel crystal structure, the space group of Fe3O4 is FD3m, and it has a lattice parameter of α=8.397Å [9]. The anions (O2−) in the lattice unit are closely packed in a cubic arrangement. There are two distinct cation sites within the unit: the A site is occupied by Fe(III), surrounded by oxygen ions to form a tetrahedral structure, and the B site is occupied by an equal amount of Fe(III) and Fe(II), surrounded by oxygen ions to form an octahedral structure. The cations at different positions have a significant impact on the electrical and magnetic properties of Fe3O4. Firstly, due to the electron transition between Fe2+ and Fe3+ at the B site, Fe3O4 has a good electrical conductivity compared to other iron oxides (such as Fe2O3, FeO) [10]. Secondly, the spins of Fe3+ at the A site are antiparallel coupled with the spins of Fe2+ and Fe3+ at the B site through a superexchange effect, which can make Fe3O4 a ferromagnetic material [11]. In addition to its internal structural characteristics, Fe3O4 also exhibits a high Curie temperature (∼860K), high spin polarization (close to 100%), and the Verwey transition at 120K [12].

Preparation method of Fe3O4 nanoparticlesCurrently, the primary methods for preparing magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles include precipitation, thermal decomposition, microemulsion, sol–gel, hydrothermal, and solvent-thermal methods [13–17]. The precipitation method is the most commonly used, and according to the precipitation principle, it can be classified as co-precipitation, oxidative precipitation, and reductive precipitation (Fig. 2). The co-precipitation method typically involves adding precipitating agents (such as sodium hydroxide or ammonia) to a solution containing Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions, causing the ions to precipitate as hydroxides. Subsequently, Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) are obtained through water loss and other treatments. During the preparation process, particles may agglomerate, so polymeric surfactant are often added to the solution to avoid this. The oxidation precipitation method generally uses an oxidant to oxidize Fe2+ to produce Fe3O4 NPs. The reduction precipitation method generally uses reducing agents (I−, SOA) to reduce Fe3+and prepare Fe3O4 NPs. Oxidation precipitation can be divided into compound oxidation precipitation and air oxidation precipitation. The precipitation method for preparing Fe3O4 NPs has the advantages of low cost, low reaction temperature, small particle size, narrow particle size distribution, and high product purity. However, the particles are prone to agglomeration during the reaction process. Particle agglomeration can be reduced by improving the stirring method and selecting suitable surfactants. Thermal decomposition method is a method of obtaining Fe3O4 NPs by mixing iron organic precursors like ferric pentacarbonyl [Fe(CO)5], ferric acetylacetonate [Fe(acac)3], ferrocene [Fe(C5H5)2], and iron oleate with surfactants in organic solvents with high boiling points, and heating them to reflux temperature. To obtain monodisperse particles, some polymers (such as oleic acid, oleamine, octadecene, tetradecene, etc.) are used as stabilizers to participate in the reaction. The thermal decomposition method has been widely used to synthesize Fe3O4 NPs, and the obtained Fe3O4 has high dispersion, high crystallinity, better monodispersity, and a narrow particle size distribution. However, the thermal decomposition method has problems such as high cost, low yield, safety hazards, and difficult industrialization. In the continuous oil phase medium, monodisperse aqueous droplets diffuse, collide, coalesce and break with each other constantly, and substance exchange is carried out in the droplets continuously, so as to prepare Fe3O4 NPs, which is called micro lotion method. The particle size distribution prepared by the micro lotion method is narrow, and it is easy to control the morphology. However, the general product output is low, and the amount of raw materials is large, so the cost is high, and the cycle is long, and it is not easy to deal with later. The sol–gel method utilizes Fe3O4 precursors to undergo polymerization and condensation reactions to form a sol. Then, the sol undergoes a crucial transformation into a gel through gelation. Finally, Fe3O4 NPs are acquired via heat treatment and other techniques. The Fe3O4 NPs obtained via the sol–gel method exhibit high mechanical strength, thermal and chemical stability, a larger specific surface area, and improved performance, and their phase state varies with different reaction temperatures and atmospheres. Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods involve preparing Fe3O4 NPs through chemical reactions in aqueous or non-aqueous solutions at high temperatures (usually 130–250°C) in closed containers under high pressure (typically 0.34MPa). The hydrothermal and solvothermal methods can prepare Fe3O4 particles with good crystal morphology, high purity, and good dispersibility. The raw materials are easy to obtain and the cost is low, but the requirements for reaction equipment are high.

Surface functionalization of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticlesSince the prepared Fe3O4 NPs are prone to aggregation and oxidation, their surfaces need to be functionalized by purposefully altering the physicochemical properties of the particle surfaces, such as surface chemical structure, surface hydrophobicity, chemical adsorption and reaction properties [18–20]. As shown in Fig. 3, the commonly used surface modification methods of Fe3O4 nanoparticles mainly include surface chemical methods [21], precipitation reaction methods [22], sol–gel methods and electrostatic self-assembly methods [23,24]. Surface chemistry method is the main method for surface modification of Fe3O4 particles, which utilizes the adsorption or chemical reaction of functional groups in organic molecules on the surface of Fe3O4 particles to locally coat the particle surface and make it organic. The surface modifiers utilized in surface chemical modification are mostly anionic surfactants [25], non-ionic surfactants [26], and organic polymers with functional groups [27], such as oleic acid, lauric acid, sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate, and other anionic surfactants. Precipitation reaction modification refers to forming a coating layer by the precipitation reaction of inorganic compounds on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs, which improves its oxidation resistance and dispersion. In addition, the Fe3O4 NPs obtained by co-precipitation can be acidified in a sodium silicate solution to obtain core–shell magnetic particles coated with a SiO2 layer on the surface [28]. The steric effect of SiO2 limits the agglomeration and continuous growth of Fe3O4 crystallites [29–31], resulting in the dispersion of the Fe3O4 core in the product and maintaining a smaller grain size, and the coated product exhibits superparamagnetism while also improving the weathering resistance of the magnetic component. Sol–gel process refers to the formation of three-dimensional network structure by various reactions of inorganic precursors [32]. SiO2 is the most widely used surface modifier to adjust the surface and interface properties of Fe3O4 modified by sol–gel method [33]. The method usually uses tetraethyl orthosilicate as the raw material to improve the stability of Fe3O4 NPs by optimizing the hydrolysis conditions to coat a layer of SiO2 on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs. Electrostatic self-assembly, also known as layer-by-layer self-assembly [34], is a novel method for the self-assembly of Fe3O4 NPs in recent years. It provides a new option for synthesizing novel, stable, and functionalized Fe3O4 core–shell microspheres. It is technically simple and easy to perform without requiring any particular device and uses water as a solvent.

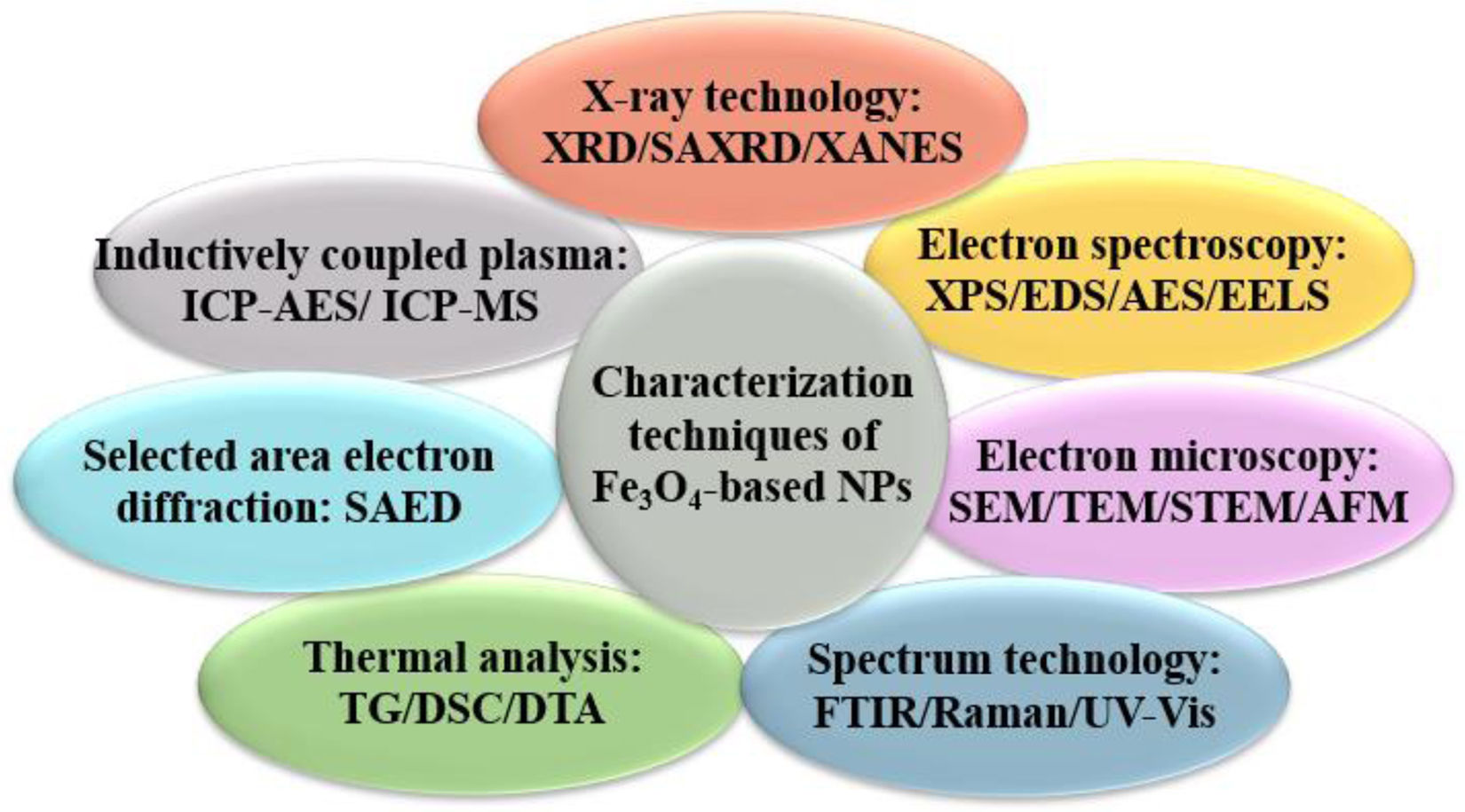

Characterization technologiesThe preformance of Fe3O4 and functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanomaterials are intrinsically linked to their structures [35]. Investigating its structures is crucial for comprehending magnetic nanomaterials’ properties and potential applications. Therefore, the characterization of magnetic nanomaterials is an important research topic in nanotechnology. The primary purpose of characterizing magnetic nanomaterials is to determine their physical and chemical properties, such as morphology [36], particle size [37], chemical composition [38], crystal structure, atomic structure, electronic structure, and band gap structure [39]. As shown in Fig. 4, currently, the characterization techniques of Fe3O4-based magnetic nanomaterials mainly include X-ray technology [40], electron spectroscopy technology [41], electron microscopy technology [42], spectrum technology [43], thermal analysis technology [44], selected area electron diffraction (SAED) technology [45], and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) technology [46].

As shown in Fig. 5, generally, in the XRD characterization, we can obtain the following information from the XRD diffraction peak: (1) The material composition and crystal phase can be determined by diffraction peaks at specific positions (the 2θ peak position of the substance) [47]. (2) The crystallinity of the crystal (or the relative proportion of each component in the composite material) can be preliminarily determined by the height and width of the diffraction peaks. (3) The change of diffraction peak position determines the change of lattice parameters (such as interplanar spacing and alloying degree) [48]. (4) The average crystal size of nanomaterials was calculated by the Scherrer formula (D=Kγ/bcostθ) [49]. In SEM and TEM characterization, the following information can be obtained from SEM and TEM images [50–54]: (1) The overall morphology of the sample can be observed through low magnification SEM, while the surface nanostructure of the sample can be observed through high magnification SEM. (2) Low magnification TEM can observe the internal structure of the sample (such as hollow structure), while high magnification TEM can observe the nanocrystalline structure of the sample (such as crystal plane spacing). (3) By comparing SEM and TEM images, the surface and internal structure of nanomaterials can be comprehensively and scientifically demonstrated. In HR-TEM and STEM characterization, the following information can be obtained [55–58]: (1) By using HR-TEM images and their Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) images, the distance between light and dark fringes on different crystal planes can be accurately measured. (2) HR-TEM images can also measure the high refractive index Facet, entangled crystals and crystal boundaries of nanomaterials. (3) HAADF-STEM images can characterize the atomic arrangement structure (atomic column and atomic structure) of nanocrystals. Generally speaking, the main functions of an energy spectrometer test include [59–61]: (1) The SEM-based spectrometer can analyze the elemental composition and distribution of materials with micron structures (or micron regions of materials). (2) TEM-based energy spectrum analysis can analyze the elemental composition and distribution of nanostructured materials (or nanoregions of materials). (3) The spectrometer based on STEM can analyze the elemental composition and distribution of atomic structural materials (or atomic regions of materials). Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) and superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) are commonly used characterization methods for analyzing the magnetic behavior of magnetic materials [62,63]. Static magnetic parameters such as magnetization strength, coercivity, Curie temperature, and magnetic energy product of magnetic materials can be obtained by VSM and SQUID, as well as dynamic magnetic properties such as their dynamic magnetization response [64]. However, there is a significant difference in the application conditions between VSM and SQUID. On the one hand, SQUID has higher measurement accuracy, up to 10−6emu, making it suitable for various magnetic samples, including weak magnetic samples. On the other hand, VSM is mainly used for block or powder materials with strong magnetism. BET is the acronym of three scientists (Brunauer, Emmett and Teller) [65]. The multi molecular layer adsorption formula derived by three scientists from classical statistical theory, also known as the famous BET equation, it has become the theoretical basis of magnetic nanoparticle surface adsorption science and is widely used in the study of magnetic nanoparticle surface adsorption performance and data processing of related detection instruments. Based on the PDOS analysis, the position of the d-band center (relative to the Fermi level) is closely related to the adsorption properties (adsorption free energy and desorption capacity) of the catalyst intermediates or products [66]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations show that the appropriate d-band center position can obtain the best intermediate adsorption and product desorption, which helps achieve an efficient electrocatalytic process [67]. The decrease in d-band energy, i.e. the decrease in d-band center, also reduces the antibonding energy band generated by coupling. The antibonding energy band has more parts below the Fermi level, which are filled with electrons and reduce the stability of the bond, resulting in a decrease in adsorption energy [68]. On the contrary, an increase in the center of the metal d-band can enhance the adsorption energy of the catalytic site toward the substrate.

Application of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticlesFunctionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (F-MNPs) are widely used in industrial, biological, and medical fields. This section systematically reviews the research status of the application of F-MNPs in the fields of interface separation, catalysis, biosensing, and medical magnetic resonance imaging.

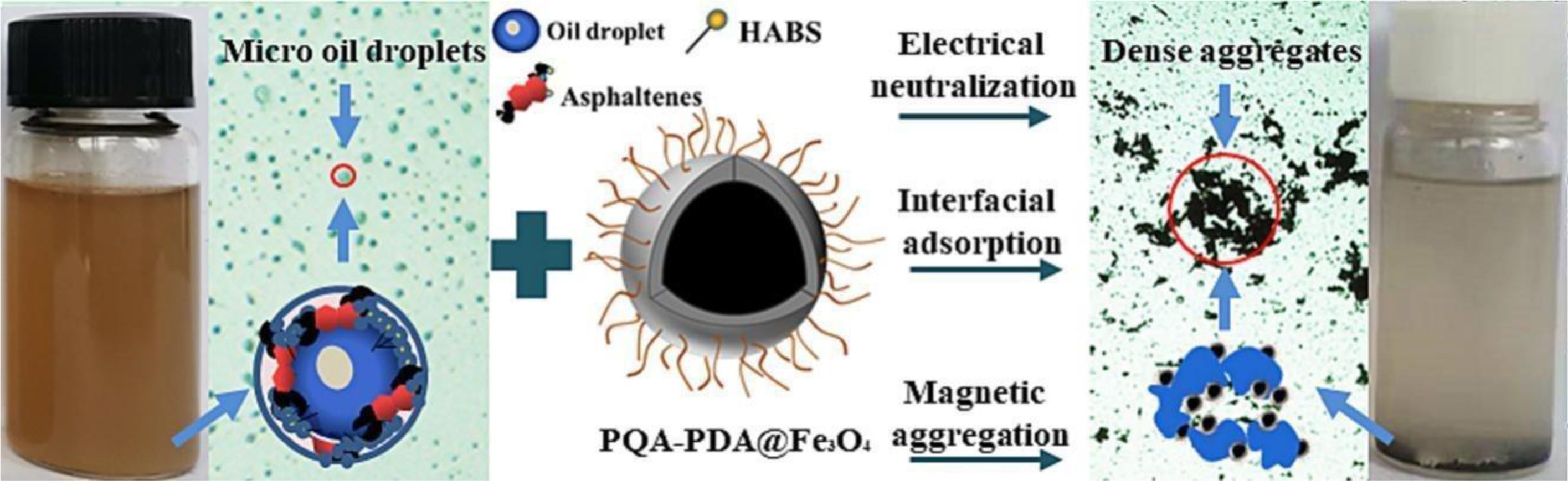

Interface separationIn the field of interface separation, F-MNPs is mainly applied to the separation between gas, liquid, and solid phases. For example, Khoshnevisan et al. [69] used magnetic field-induced mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) to separate O2 and N2 gas. The double-layered MMMs were made of polyethersulfone (PES) and Pebax-1657 and super-paramagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) by simultaneous co-casting method. The separation results indicated a substantial improvement up to 3.59 at room temperature for the sample containing 24wt% Fe3O4 NPs under the gas feeding of 10bar, whereas the selectivity for non-magnetic MMMs was ∼1.87. The results showed that the external magnetic field could facilitate the formation of magnetic channels by loosen hydrogen bonds of the carbonyl groups in the polymer and also alignment of the super-paramagnetic NPs. Li et al. [70] prepared a novel polydopamine–polyquaternium modified Fe3O4 (PQA-PDA@Fe3O4) nanoparticle integrates the electrical neutralization, interfacial adsorption and magnetic aggregation functionalities. It was used to treat the produced water that contained 500mg/L emulsified oil, which indicates the PQA-PDA@Fe3O4 nanoparticles could coalesce the fine oil droplets into large and dense aggregates, as demonstrated by the raised fractal dimension values (Fig. 6), and a demulsification efficiency of 90.5% was achieved at 200mg/L dosage. Hamedi et al. [71] coated the Fe3O4 by using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) with surfactant-to-Fe3O4 (MNPs) mass ratios of 0.4 and 0.8. Based on the oil–water separation analysis (Fig. 7), The oil–water separation results reveal that the smaller Fe3O4 coated with CTAB (Fe3O4-S@CTAB) using the lower surfactant to Fe3O4 mass ratio of 0.4 lead to the highest oil SE (around 99.8%). Xu et al. [72] synthesized an amphiphilic and magnetically recyclable graphene oxide (MR-GO) demulsifier by graft of magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SiO2-APTES) and ethylenediamine on the GO surface. In the demulsification tests, MR-GO displayed favorable demulsification performance for crude oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion under pH of 2.0–10.0, thusly greatly improving the application scope of common demulsifier. The optimal dosage of MR-GO was 200mg/L and the demulsification efficiency attained a maximum value of 99.7% for crude O/W emulsion with pH of 6.0. Besides, owing to its magnetic response performance, the MR-GO can be reused and the demulsification efficiency remained above 91.0% after six cycles. In addition, He et al. [73] grafted the PEG600–KH560 (PK) onto Fe3O4 surfaces, obtaining a kind of hydrophilically-modified recyclable nanoparticles. The nanoparticles have been further used for the enhancement of heavy oil recovery from oil sands. The floatation results show that the nanoparticles could improve oil recovery by at least 12% compared with the traditional hot water extraction process (HWEP). After the extraction, up to 70% of the nanoparticles could be directly recycled from the solution for further use. The rest of the nanoparticles are left in the oil phase and attached on the residual solid surface. The efficiency of the nanoparticles is found to be decreased when the recycling times exceed 5 due to the adsorption of oil components. However, the above research reports lack research on separation mechanisms. Based on this, our group has previously studied relevant separation mechanisms, especially the oil–water interface separation mechanism. For example, we designed and successfully synthesized a novel kind of amphiphilic magnetic demulsifier by grafting aliphatic alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether onto the surface of epoxy-functionalized magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles [6]. The bottle tests show that the F-MNPs performs well in fast (less than 5min) and relatively complete demulsifying (up to 95.5%) both water-in-oil emulsions (water-in-crude oil, water-in-bitumen) and oil-in-water emulsions (diesel-in-water, crude oil-in-water, etc.) under room temperature. It also works well in breaking the stable water-in-asphaltene emulsions, achieving the demulsification efficiency of 90.0% within 2min without heating (at 2000ppm of M-ANP) (Fig. 8). Mechanism research shows that due to the synergy of functional compound and magnetic nanoparticles, the F-MNPs can efficiently adhere to the oil–water interface, accelerate flocculation and coalescence of water droplets, and promote oil–water emulsions separation by Hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces under the external magnetic field (Fig. 9). In a word, the above research reports indicate that functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles mainly focus on improving separation performance of F-MNPs in the field of interface separation.

Schematic diagram of polydopamine-polyquaternium modified Fe3O4 (PQA-PDA@Fe3O4) nanoparticles used for treating oily wastewater.

Reproduced from Ref. [70] with permission of Elsevier.

Fe3O4 coated CTAB and SDS for oil-in-water nanoemulsions separation.

Reproduced from Ref. [71] with permission of Elsevier.

Application in the demulsification of oil–water emulsions of alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier.

Schematic demulsification mechanism of (a) water-in-oil, (b) oil-in-water emulsions by alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier.

Functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles are mainly used in the field of catalysis for thermal, photocatalytic, and electrocatalytic applications. For example, Wu et al. [74] reported a dramatically improved POWS system for a Au-supported Fe3O4/N-TiO2 superparamagnetic photocatalyst promoted by local magnetic field effects (Fig. 10). By controllable manipulation of both features using local magnetic field, an unprecedented solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency of 11.9±0.5% and an overall energy efficiency of 1.16±0.05% were achieved in a particulate POWS system under AM 1.5G simulated solar illumination. Huang et al. [75] synthesized the recyclable flower-like MoS2@Fe3O4@Cu2O like-Z-scheme heterojunction (MFC) by using magnetic assembly method (Fig. 11). This heterojunction was used for photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. The results indicated that the photocatalytic efficiency of MFC was 3.5, 1.75 and 2.5 times that of MoS2 (M), MoS2@Fe3O4 (MF) and MoS2@Cu2O (MC), respectively. Li et al. [76] Successfully designed a non-noble bimetallic catalyst of CoFe/Fe3O4 nanoparticles with a core–shell structure that is well dispersed on the defect-rich carbon substrate for the hydrogenation of CO2 under mild conditions. Based on the catalytic activity reversible regeneration mechanism (Fig. 12), the catalysts exhibit a high CO2 conversion activity with the rate of 30% and CO selectivity of 99%, and extremely robust stability without performance decay over 90h in the reverse water gas shift reaction process. Zhang et al. [77] reported a liquid-phase laser irradiation method to fabricate symbiotic graphitic carbon encapsulated amorphous iron and iron oxide nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes (Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs) (Fig. 13). Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs exhibits superior electrocatalytic activity toward urea synthesis using NO3− and CO2, affording a urea yield of 1341.3±112.6μgh−1mgcat−1 and a faradic efficiency of 16.5±6.1% at ambient conditions.

Proposed mechanism and QE tests of the POWS system. (a) Schematic illustration of the magnetic field promoted POWS system, in which the charge separation process is facilitated by the induced local magnetic field; Internal QE of N-TiO2 (b) and Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 (c) photocatalysts with and without external magnetic field. (NIR=near infrared (800–1200nm); NMF=no magnetic field; MF=magnetic field of 180mT) Error bars indicate the standard deviations; (d) repeatable tests of Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 photocatalyst at 270°C and 180mT under simulated solar irradiation. The head space of the batch reactor was purged with Ar gas at the end of each cycle. (e) Time-dependent free energy and STH conversion efficiency of the POWS reaction at 270°C under our operating conditions.

Reproduced from Ref. [74] with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry.

SEM and TEM images of M (a, d), MF (b, d) and MFC (c, f), and EDX elemental mapping images of Mo, S, Fe, O, and Cu (g–l), respectively, and HRTEM image of MFC (m).

Reproduced from Ref. [75] with permission of Elsevier.

Catalytic reaction mechanism. (a) Slab model of CoFe/Fe3O4 core/shell structure, and the charge density difference: ΔρCoFe/oxide=ρCoFe/oxide−ρCoFe−ρoxide. The amount of transfer electron at the interface are indicated. (b) Side view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface. (c) Top view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface unit cell. The numbers at the top of the atoms indicate the different adsorption sites. (d) Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism.

Reproduced from Ref. [76] with permission of WILEY-VCH.

(a) LSV curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in Ar- and CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 electrolytes. (b) The chronoamperometry curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 with different potentials. (c) The dependence of urea yield and FE of Fe@C-Fe3O4/CNTs on potential. (d) The stability test of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs for urea synthesis.

Reproduced from Ref. [77] with permission of John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

To sum up, The future research priorities for functionalized magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in the fields of photocatalysis, therm catalysis, and electrocatalysis may focus on the following areas: (1) Optimization of photocatalytic performance: Research on how to enhance the photocatalytic efficiency of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles through surface modification and structural regulation, including leveraging their unique magnetic properties to improve the separation and transfer of photogenerated charges, and exploring their application potential in the degradation of organic pollutants and water splitting. (2) Expansion of thermal catalysis applications: Studies on thermal catalysis using magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles may focus on how to regulate catalytic activity and selectivity by altering their surface chemical properties, as well as how to utilize their magnetism for catalyst recovery and reuse. (3) Enhancement of electrocatalytic performance: Future research may concentrate on how to enhance the performance of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in electrocatalytic processes such as oxygen reduction reaction and hydrogen evolution reaction through nanostructure design and the fabrication of composite materials, and how to optimize their catalytic activity through electric field regulation. (4) Exploration of multimodal catalysis mechanisms: Combining various stimulation methods like light, heat, and electricity, research may explore the synergistic effects of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in multimodal catalysis and how multimodal stimulation can achieve more efficient catalytic reactions. (5) Environmental and biocompatibility studies: Considering the safety and sustainability of practical applications, future studies may pay more attention to the environmental and biocompatibility of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, including their stability, toxicity assessment, and biodegradability in biological systems. (6) Scalable preparation and application: Research on how to achieve scalable production of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and how to integrate them into actual catalytic systems for industrial-level applications. (7) Theoretical calculations and simulations: Utilizing computational chemistry and materials science methods to simulate and predict the catalytic behavior of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, and how theoretical guidance can optimize their catalytic performance through experimental design. These research priorities will help advance the application of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in the field of catalysis and provide new strategies and materials for solving energy and environmental issues.

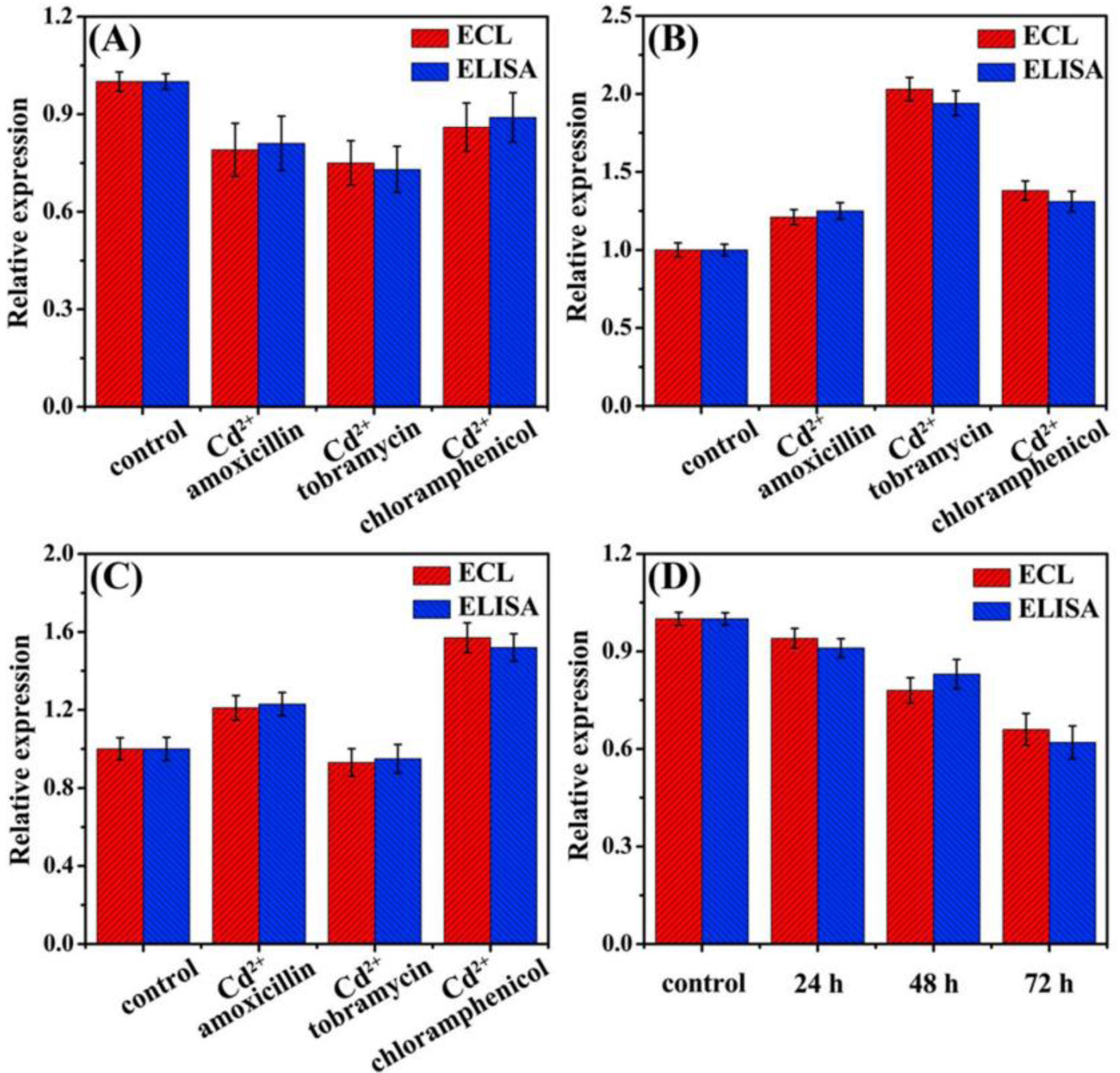

BiosensingF-Fe3O4 nanoparticles are highly applicable in the field of biosensing, primarily due to their unique physicochemical properties. Firstly, these nanoparticles possess superparamagnetism, allowing them to respond rapidly to an external magnetic field, the characteristic that enables them to serve as signal amplifiers or markers in biosensing, thereby enhancing detection sensitivity and speed. Secondly, the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles is easily functionalized, allowing for the modification with various functional groups or biomolecules such as antibodies, enzymes, or nucleic acids, achieving specific recognition of particular biomarkers. Moreover, the large surface area of magnetic nanoparticles provides more active sites for molecular immobilization and biomolecule loading, enhancing their potential in biosensing applications. For instance, as shown in Fig. 14, Shi et al. [78] developed and validated a new type of reliable wireless, battery-free, and implantable sensing system (RWBS) for the real-time monitoring of physiological bending of spines and joints. The RWBS exploits the unique movement-sensing capabilities of an implantable flexible magnetic strip, the signals from which are detected with an external receiver. We implanted this magnetic strip beneath the skins of Sprague Dawley rats and human cadavers and demonstrated that in combination with the receiver, the magnetic strip enabled real-time in vivo and wireless monitoring of motions in both rats (anesthetized/awake) and human cadavers. Karaca et al. [79] prepared (Fe3O4/Pt and Fe3O4-OH/Pt) micromotors by Pt coating of one side of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-OH nanoparticles using by RF magnetron sputtering method. These Janus micromotors were used in miRNA-21 biosensing. The changes in the fluorescence intensity and in the speed of micromotors were examined after hybridization. Performances of these two novel micromotors were compared to present their potential use in early cancer diagnosis. Promising results with the functionalized Fe3O4-OH/Pt micromotors were obtained. Kim et al. [80] developed A nanostructured multicatalyst system consisting of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) as peroxidase mimetics and an oxidative enzyme entrapped in large-pore-sized mesoporous silica for convenient colorimetric detection of biologically important target molecules. Tu et al. [81] designed a facile and signal-on photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensing strategy based on hypotoxic Cu2ZnSnS4 NPs nanoparticles (NPs) and biofunctionalized Fe3O4 NPs that integrated recognition units with signal elements, without the need for immobilization of probes on the electrode (Fig. 15). The developed PEC biosensing platform exhibited satisfactory stability, excellent specificity, and favorable accuracy for miRNA-155, which would have a promising prospect for monitoring miRNA expression in tumor cells. Yue et al. [82] developed a label-free electrochemical biosensing system for the sensitive detection of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which was frequently overexpressed in lung cancer, breast cancer, and glioblastoma. The biosensing system has the potential to be developed as a valuable tool in clinical EGFR detection, offering a promising candidate for point-of-care (POC) testing. As shown in Fig. 16, Sui et al. [83] constructed an electrochemiluminescence sensor for 5hmC detection based on thiol functional Fe3O4 magnetic beads and covalent chemical reaction of CH2OH in 5hmC. In order to testify the accuracy of the biosensor, the detection results were also compared with that by MethylFlash Global DNA Hydroxymethylation (5hmC) ELISA Easy Kit (Epigentek, USA). As illustrated in Fig. 17, there is almost no difference in the results of the two methods, indicating the superior practicability of the biosensor. Liu et al. [84] utilized the unique electrical and optical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) as substrates for SPR sensing, significantly improving sensitivity. In addition, sp2 hybrid SWCNTs possess the ability to load specific recognition elements. In addition, through the coordination interaction between titanium and phosphate groups and the ferromagnetism of Fe3O4, with the help of an external magnetic field, exosomes can be efficiently separated and enriched in complex samples. Because the Fe3O4@TiO2 of the high quality and high RI of the SPR biosensor amplify the response signal, thereby further improving its performance. The linear range of the SPR biosensor constructed by this method was 1.0×103–1.0×107particles/mL, with a detection limit of 31.9particles/mL. In clinical serum sample analysis, the area under the curve is 0.9835, which can distinguish tumor patients from healthy individuals. Besides, Hu et al. [85] fabricated a fluorescent biosensor for ochratoxin A on the basis of a new nanocomposite (Fe3O4/g-C3N4/HKUST-1 composites). Fe3O4/g-C3N4/HKUST-1 composites have strong adsorption capacity for dye-labeled aptamer and are able to completely quench the fluorescence of the dye through the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism. In the presence of ochratoxin A (OTA), it can bind with the aptamer with high affinity, causing the releasing of the dye-labeled aptamer from the Fe3O4/g-C3N4/HKUST-1 and therefore results in the recovery of fluorescence.

Wireless, battery free, implantable bending sensing system based on flexible magnetic strips.

Reproduced from Ref. [78] with permission of Elsevier.

Schematic illustration of (A) the preparation of biofunctionalized porous Fe3O4 NPs and (B) the construction of a PEC biosensing platform for miRNA.

Reproduced from Ref. [81] with permission of Elsevier.

Schematic illustration of the ECL biosensor construction process and 5hmC detection.

Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier.

Effect of different antibiotics and Cd2þ complex pollutants on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of rice seedling roots (A), stems (B) and leaves (C). Effect of ALV-J on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of chicken embryo fibroblast cell for 24, 48, 72h (D).

Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier.

In summary, the application prospects of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in biosensing are broad, and future research priorities may focus on the following key areas. (1) Enhancing sensitivity and selectivity: By optimizing the surface functionalization of nanoparticles to enhance their recognition capabilities for specific biomolecules, the sensitivity and selectivity of biosensors can be improved. This may involve the design and synthesis of new functional groups and precise control of the surface properties of nanoparticles. (2) Biocompatibility and biodegradability studies: To ensure the safety of nanoparticles within the body, future research will focus more on their biocompatibility and biodegradability. This includes studying the degradation pathways of nanoparticles, potential toxicity, and immune responses. (3) Development of multimodal sensing platforms: Combining the magnetic properties of magnetic nanoparticles with other physicochemical characteristics to develop multimodal sensing platforms that can respond to multiple biomarkers simultaneously. This may involve integrating nanoparticles with other signal transduction mechanisms (such as optical, electrochemical, and thermal). (4) Real-time monitoring and imaging technologies: Utilizing the responsiveness of magnetic nanoparticles to magnetic fields to develop new technologies for real-time monitoring of biological processes and disease progression. This may include the development of new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents and magnetic particle imaging techniques. (5) Intelligentization and remote control: Research on how to achieve remote control of nanoparticle behavior through external magnetic fields to precisely regulate biosensing processes. (6) Large-scale production and cost-effectiveness analysis: To promote the widespread application of functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in biosensors, future research will focus on large-scale production technologies and how to reduce costs and improve production efficiency. (7) Environmental and clinical application studies: Exploring the application of nanoparticles in environmental monitoring and clinical diagnostics, including high-sensitivity detection of environmental pollutants and disease markers. (8) Interdisciplinary research: Encouraging collaboration between experts in materials science, biology, medicine, chemistry, and engineering to address key scientific issues in biosensing. These research priorities will help advance innovation and application of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the field of biosensing, providing more efficient and reliable technological means for early disease diagnosis, therapeutic monitoring, and environmental testing.

Medical magnetic resonance imagingThe development of a multifunctional integrated diagnosis and treatment nano platform plays a crucial role in the development of precision medicine. In recent years, many diagnostic and therapeutic nanoplatforms have been synthesized for efficient imaging guided treatment of different diseases [86,87]. In most cases, composite systems loaded with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (size greater than 5nm) have been developed for Medical magnetic resonance imaging. For example, traditional T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents have defects inherent to negative contrast agents, while chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents can quantify substances at trace concentrations. After reaching a certain concentration, iron-based contrast agents can “shut down” CEST signals. The application range of T2 contrast agents can be widened through a combination of CEST and T2 contrast agents, which has promising application prospects. Based on this, Hu et al. [88] developed a T2 MRI negative contrast agent with a controllable size and to explore the feasibility of dual contrast enhancement by combining T2 with CEST contrast agents. It founds that Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) with a mean particle size of 82.6±22.4nm modified with −OH active functional groups. They exhibited self-aggregation in an acidic environment. The CEST effect was enhanced as the B1 field increased, and an in vitro pH map was successfully plotted using the ratio method. Fe3O4 NPs could stably serve as reference agents at different pH values. Zhao et al. [89] reported the fabrication of magnetite hybrid nanostructures employing Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) to form multifunctional magnetite nanoclusters (NCs) by combining an oil-in-water microemulsion assembly and a layer-by-layer (LBL) method. The Fe3O4 NCs were firstly prepared via a microemulsion self-assembly technique. Then, polyelectrolyte layers composed of poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) and doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) were capped on Fe3O4 NCs to construct the Fe3O4 NC/PAH/PSS/DOX hybrid nanostructures via LBL method (Fig. 18). The as-prepared hybrid nanostructures loaded with DOX demonstrated the pH-responsive drug release and higher cytotoxicity toward human lung cancer (A549) cells in vitro and can serve as T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents, which can significantly improve T2 relaxivity and lead to a better cellular MRI contrast effect. The loaded DOX emitting red signals under excitation with 490nm are suitable for bioimaging applications. Li et al. [90] fabricated chiral iron oxide supraparticles (Fe3O4 SPs) modified by chiral penicillamine (Pen) molecules with g-factor of ≈2×10−3 at 415nm. These SPs act as high-quality magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents. Therein, the transverse relaxation efficiency and T2-MRI results demonstrated chiral Fe3O4 SPs have a r2 relaxivity of 157.39±2.34mM−1S−1 for D-Fe3O4 SPs and 136.21±1.26mM−1S−1 for L-Fe3O4 SPs due to enhanced electronic transition dipole moment for D-Fe3O4 SPs compared with L-Fe3O4 SPs. These results certainly confirm that the chiral Fe3O4 SPs showed good sensitivity and versatility in in vivo T2-MRI for tumor imaging, with the D-Fe3O4 SPs exhibiting a more outstanding imaging performance as a potential MRI contrast agent (Fig. 19). As shown in Fig. 20, Yu et al. [91] have reported an ROS nanoreactor based on core–shell-structured iron carbide (Fe5C2@Fe3O4) nanoparticles (NPs) through the catalysis of the Fenton reaction. These NPs are able to release ferrous ions in acidic environments to disproportionate H2O2 into ·OH radicals, which effectively inhibits the proliferation of tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. The high magnetization of Fe5C2@Fe3O4 NPs is favorable for both magnetic targeting and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Mistral et al. [92] proposed to use chitosan (CS) coatings as a means to tune the biocompatibility and magnetic properties of the SPIONs. For this purpose, magnetite (Fe3O4) SPIONs with various CS coatings were synthesized. CS with identical degree of polymerization (DPw=450) but different degrees of acetylation (DA of 1, 14, and 34%) were employed to tune the hydrophilic properties of the SPIONs’ coatings. In addition, the multimodal features of the SPIONs were evidenced by performing magnetic hyperthermia and MRI measurements. Despite significant differences, for all the CS-coated SPIONs, the magnetic properties remained strong enough to envision their use in various biomedical applications such as magnetic hyperthermia, MRI contrast agents, magnetic field-assisted drug delivery, and as platforms for further biological functionalization.

Schematic illustration of synthesis of Fe3O4 NC/PAH/PSS/DOX hybrid nanostructures as theranostic agents for MRI and drug delivery.

Reproduced from Ref. [89] with permission of Springer Nature.

In vivo MRI performance and tumor-targeting diagnosis ability of chiral Fe3O4 SPs. (A) T2WI images for the liver site of BALB/c mice before and after 30min tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, D-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1. (B) The statistical results of the contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the liver site of BALB/c mice, compared with the pre-injection group, after tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, DL-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1 for 30min. Tumor diagnosis resolution of chiral Fe3O4 SPs compared to Ferumoxytol in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice at the injection dose of 10mgkg−1, with (C) the T2WI images and (D) the statistic results of contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the 4T1 tumor site at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Broad tumor diagnosis by D-Fe3O4 SPs in (a) RM-1 tumor and (b) B16F10 tumor model mice, with (E) T2WI images and (F) the statistic contrast ratio at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Error bars are obtained from three parallel samples. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA.

Reproduced from Ref. [90] with permission of John Wiley and Sons.

Schematic illustration of Fe5C2@Fe3O4 NPs for pH-responsive Fe2+ release, ROS, and T2/T1 signal conversion.

Reproduced from Ref. [91] with permission of American Chemical Society.

In addition, as is known to all, MRI is often combined with hyperthermia techniques to identify tumor cells [93,94]. MRI can monitor the temperature changes of tumor tissues in real time during the hyperthermia process. Through Magnetic Resonance Temperature Imaging (MRTI) technology, it is possible to accurately measure the temperature distribution within the tumor, thereby ensuring that the temperature of hyperthermia is controlled within an effective range. This real-time monitoring and feedback control helps to improve the precision and safety of hyperthermia, and can also indirectly reflect the response of tumor cells through temperature changes. During this monitoring process, F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles can be used as the medium for hyperthermia. These nanoparticles can generate heat under the influence of an alternating magnetic field, and these nanoparticles can also serve as a contrast agent for MRI, enhancing the imaging contrast of tumor tissues [95]. In this way, MRI can not only monitor the hyperthermia process, but also more clearly identify tumor cells, thereby improving the accuracy of cancer diagnosis [96]. For example, according to the Magnetic particle hyperthermia (MPH) enables the direct heating of solid tumors with alternating magnetic fields (AMFs), and Magnetic particle imaging (MPI) can measure the nanoparticle content and distribution in tissue after delivery. Hayden Carlton et al. [97] conducted MPH experiments in tumor-bearing mouse cadavers and finite element calculations. It founds that the utility of MPI to guide predictive thermal calculations for MPH treatment planning. Jules Mistral et al. [92] Synthesized magnetite (Fe3O4) superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) with various chitosan coatings, the multimodal features of the SPIONs were evidenced by performing magnetic hyperthermia and MRI measurements. The results suggested that the magnetic properties remained strong enough to envision their use in biomedical application of magnetic hyperthermia. K. Rekha et al. [98] synthesized a set of citric acid functionalized Fe3O4 nanoclusters by a solvothermal technique with the aim of enhancing their suitability for cancer therapy utilizing variable solvothermal temperatures. The efficiency of the induction heating for the synthesized NCs under an alternating magnetic field using specific absorption rate (SAR) measurements were investigated, and it is possible to generate thermal energy, and the calculation of the specific absorption rate (SAR) values indicated that the samples were a viable option for hyperthermia treatment. However, F-Fe3O4 still have some potential drawbacks when used in MRI and high-temperature hyperthermia. Firstly, biocompatibility and toxicity are key challenges. Although functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles themselves have good biocompatibility, long-term accumulation in the body may trigger potential toxic reactions and increase the burden on organs such as the liver and spleen. Moreover, cellular uptake of nanoparticles can restrict their Brownian motion, leading to particle aggregation, reduced specific absorption rate (SAR), and decreased heat generation. Secondly, the preparation process of functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles is complex and requires precise control over size, shape, and surface modification. Ultrasmall nanoparticles have better T1 contrast effects, but they are difficult to prepare and prone to aggregation. Surface modification can enhance stability, but improper modification may lead to aggregation or degradation, affecting performance. Lastly, there are limitations in imaging and therapeutic effects. When used as T2 contrast agents, functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles may cause the “blooming effect,” resulting in blurred images and difficulty in distinguishing tumors from other low-signal areas. When used as T1 contrast agents, their effectiveness is limited by their high magnetic moment. In high-temperature hyperthermia, heating efficiency is significantly affected by particle size, shape, and alternating magnetic field parameters. Although superparamagnetic F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles have good dispersibility, their heating power is low, and a high dose is required to achieve therapeutic effects.

To sum up, F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles hold significant potential in the field of functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) due to their unique properties. The future research priorities in this area may include the following content. (1) Enhancing contrast and sensitivity: Developing nanoparticles with improved magnetic properties to enhance the contrast and sensitivity of MRI scans [99]. This could involve engineering nanoparticles with higher relaxivity values, allowing for clearer imaging of soft tissues and better detection of pathological changes. (2) Targeted drug delivery systems: Researching the use of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles as targeted drug delivery systems [100]. By attaching specific ligands or antibodies to the nanoparticle surface, these nanoparticles could be directed to specific cells or tissues, improving the efficacy of treatments and reducing side effects. (3) Multimodal imaging: Exploring the potential of these nanoparticles for multimodal imaging, combining MRI with other imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography (PET) or computed tomography (CT) [101–103]. This could provide a more comprehensive view of biological processes and disease states. (4) Therapeutic applications: Investigating the therapeutic applications of magnetic nanoparticles [104], such as hyperthermia treatments for cancer, where the heat generated by the nanoparticles under an alternating magnetic field can destroy tumor cells [105–107]. (5) Biodegradability and biocompatibility: Ensuring that the F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles used are biodegradable and biocompatible is crucial for clinical applications. Future research will focus on the development of nanoparticles that can be safely metabolized and excreted by the body, reducing the risk of long-term toxicity. (6) Real-time imaging and monitoring: Developing methods for real-time imaging and monitoring of nanoparticle distribution and behavior within the body [108–110], which could be used for tracking the progress of treatments and adjusting therapies accordingly. (7) Nanotoxicity and safety studies: Conducting thorough nanotoxicity studies to understand the potential risks associated with the use of magnetic nanoparticles in the body, ensuring their safe use in clinical settings [111]. (8) Clinical trials and translational research: Advancing from preclinical studies to clinical trials, focusing on the translation of laboratory research into practical clinical applications [112–114]. These research priorities aim to harness the full potential of functionalized magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in MRI and related medical applications, providing more effective diagnostic and therapeutic options [115–117]. The progress in these areas will rely on interdisciplinary collaboration and the integration of new technologies, such as nanotechnology, bioengineering, and advanced imaging techniques.

PerspectivesFunctionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, due to their unique physical and chemical properties, have shown extensive application potential in fields such as biomedical, environmental governance, energy storage, and catalysis [118]. Future research on functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles should focus on the following aspects. (1) Develop new synthetic methods to enhance the magnetic properties of F-MNPs, such as magnetization and coercivity. Optimize the size, shape, and crystal structure of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles to accurately prepare highly dispersed functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles to meet specific application requirements. (2) Study different surface modifiers, such as polymers, biomolecules, inorganic materials, etc., to improve the stability, biocompatibility, and targeting of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Further evaluating and improving the biocompatibility of magnetic nanoparticles to reduce potential toxicity to living organisms. In addition, further research is needed on its metabolic pathways and biodegradability in living organisms. (3) Develop functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles with active targeting capability to improve the accuracy and efficiency of drug delivery. Further research on stimulus responsive drug release systems, such as pH sensitive, temperature sensitive, or light sensitive release mechanisms. (4) In the field of functional magnetic resonance imaging, based on functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, it is necessary to further improve the performance of magnetic resonance contrast agents, enhance the clarity and contrast of functional magnetic resonance imaging, and ultimately study multifunctional MRI contrast agents that integrate diagnosis and treatment. In addition, F-Fe3O4 are ideal candidates for imaging-guided cancer therapy because they can not only visualize tumors that are invisible in non-contrast scans but also provide magnetic fluid hyperthermia (MFH) treatment [119]. Currently, ultrasound, CT, and MRI are commonly used to guide radiofrequency ablation probes during hyperthermia and to assess the outcomes of such treatments. In the evolving field of medical imaging, hyperthermia guidance can be provided in many other ways, although some options have not yet demonstrated sufficient translational potential. For example, the introduction of magnetomotive optical coherence tomography (MM-OCT) into clinical practice may help guide hyperthermia [120,121]. MM-OCT is a high-resolution technique that can image the microstructure of tumors and reveal tissue response to hyperthermia in real time. Incorporating MM-OCT functionality into handheld or catheter-based device platforms could enable in situ assessment of thermal dose, which would complement existing imaging techniques by providing immediate feedback on the physiological effects of high temperatures, thereby enhancing the precision and efficiency of MFH treatment. (5) Evaluating the long-term safety of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, including environmental safety and human health risks. Developing relevant industry standards and norms to ensure the safety of its application. Researching the large-scale production technology of magnetic nanoparticles, reducing costs, and improving market competitiveness. Carrying out a cost-benefit analysis to evaluate its economic feasibility in different application fields. (6) Promoting communication and cooperation between different disciplines such as physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, and engineering. Facilitating the application of F-MNPs in new materials, equipment, and processes.

In summary, functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, as a multidisciplinary fusion product, have broad application prospects in fields such as interface separation, catalysis, biosensing, and medical magnetic resonance imaging. With the continuous advancement and innovation of technology, the performance of these functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles will be further improved, and their application fields will also be further expanded. Future research needs to focus on improving its stability, biocompatibility, and environmental friendliness, while addressing cost and scale issues in the industrialization process. In a word, F-MNPs are expected to play a critical role in future scientific research and industrial applications through interdisciplinary cooperation.

ConclusionsSurface functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles are widely used in industrial, biological, and medical fields due to its significant characteristics such as nanoparticle effect, surface effect, and magnetic responsiveness. This work reviewed the basic theories of functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, including structural characteristics, magnetic behavior, preparation methods, and characterization techniques. Then, based on the fundamental theories, the applications of F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in important fields (such as oil–water interface separation, photocatalysis, thermal catalysis and electrocatalysis, biosensing and medical magnetic resonance imaging) were systematically reviewed. Finally, the paper delves into the scientific challenges faced by F-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in various application fields, thereby providing potential insights and directions for the further development of F-MNPs nanoparticles. In summary, the preparation and application of functionalized magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles is a field full of challenges and opportunities. Future research needs to focus on the integration of basic science and applied technology, while considering social ethics and environmental sustainability. Through interdisciplinary collaboration and technological innovation, functionalized magnetic nanoparticles are expected to make breakthrough progress in various fields. Moreover, with continuous technological innovation and interdisciplinary cooperation, future research will be able to overcome the limitations of existing technologies, achieving large-scale production and widespread application of high-performance Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Associated contentSupplementary material.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work was supported by Clinical Project of Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (Grant No. 2021-GMHCT-024), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22208071), Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (Grant No. QKHJC-ZK[2022]YB088).

![Schematic diagram of polydopamine-polyquaternium modified Fe3O4 (PQA-PDA@Fe3O4) nanoparticles used for treating oily wastewater. Reproduced from Ref. [70] with permission of Elsevier. Schematic diagram of polydopamine-polyquaternium modified Fe3O4 (PQA-PDA@Fe3O4) nanoparticles used for treating oily wastewater. Reproduced from Ref. [70] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr6.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Fe3O4 coated CTAB and SDS for oil-in-water nanoemulsions separation. Reproduced from Ref. [71] with permission of Elsevier. Fe3O4 coated CTAB and SDS for oil-in-water nanoemulsions separation. Reproduced from Ref. [71] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr7.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Application in the demulsification of oil–water emulsions of alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier. Application in the demulsification of oil–water emulsions of alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr8.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Schematic demulsification mechanism of (a) water-in-oil, (b) oil-in-water emulsions by alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier. Schematic demulsification mechanism of (a) water-in-oil, (b) oil-in-water emulsions by alcohol nonionic propylene oxide-ethylene oxide block polyether modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Reproduced from Ref. [6] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr9.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Proposed mechanism and QE tests of the POWS system. (a) Schematic illustration of the magnetic field promoted POWS system, in which the charge separation process is facilitated by the induced local magnetic field; Internal QE of N-TiO2 (b) and Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 (c) photocatalysts with and without external magnetic field. (NIR=near infrared (800–1200nm); NMF=no magnetic field; MF=magnetic field of 180mT) Error bars indicate the standard deviations; (d) repeatable tests of Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 photocatalyst at 270°C and 180mT under simulated solar irradiation. The head space of the batch reactor was purged with Ar gas at the end of each cycle. (e) Time-dependent free energy and STH conversion efficiency of the POWS reaction at 270°C under our operating conditions. Reproduced from Ref. [74] with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry. Proposed mechanism and QE tests of the POWS system. (a) Schematic illustration of the magnetic field promoted POWS system, in which the charge separation process is facilitated by the induced local magnetic field; Internal QE of N-TiO2 (b) and Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 (c) photocatalysts with and without external magnetic field. (NIR=near infrared (800–1200nm); NMF=no magnetic field; MF=magnetic field of 180mT) Error bars indicate the standard deviations; (d) repeatable tests of Fe3O4/N-TiO2-4 photocatalyst at 270°C and 180mT under simulated solar irradiation. The head space of the batch reactor was purged with Ar gas at the end of each cycle. (e) Time-dependent free energy and STH conversion efficiency of the POWS reaction at 270°C under our operating conditions. Reproduced from Ref. [74] with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr10.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![SEM and TEM images of M (a, d), MF (b, d) and MFC (c, f), and EDX elemental mapping images of Mo, S, Fe, O, and Cu (g–l), respectively, and HRTEM image of MFC (m). Reproduced from Ref. [75] with permission of Elsevier. SEM and TEM images of M (a, d), MF (b, d) and MFC (c, f), and EDX elemental mapping images of Mo, S, Fe, O, and Cu (g–l), respectively, and HRTEM image of MFC (m). Reproduced from Ref. [75] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr11.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Catalytic reaction mechanism. (a) Slab model of CoFe/Fe3O4 core/shell structure, and the charge density difference: ΔρCoFe/oxide=ρCoFe/oxide−ρCoFe−ρoxide. The amount of transfer electron at the interface are indicated. (b) Side view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface. (c) Top view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface unit cell. The numbers at the top of the atoms indicate the different adsorption sites. (d) Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism. Reproduced from Ref. [76] with permission of WILEY-VCH. Catalytic reaction mechanism. (a) Slab model of CoFe/Fe3O4 core/shell structure, and the charge density difference: ΔρCoFe/oxide=ρCoFe/oxide−ρCoFe−ρoxide. The amount of transfer electron at the interface are indicated. (b) Side view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface. (c) Top view of the Fe3O4 (100) surface unit cell. The numbers at the top of the atoms indicate the different adsorption sites. (d) Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism. Reproduced from Ref. [76] with permission of WILEY-VCH.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr12.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![(a) LSV curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in Ar- and CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 electrolytes. (b) The chronoamperometry curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 with different potentials. (c) The dependence of urea yield and FE of Fe@C-Fe3O4/CNTs on potential. (d) The stability test of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs for urea synthesis. Reproduced from Ref. [77] with permission of John Wiley and Sons Ltd. (a) LSV curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in Ar- and CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 electrolytes. (b) The chronoamperometry curves of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs measured in CO2-saturated 0.1M KNO3 with different potentials. (c) The dependence of urea yield and FE of Fe@C-Fe3O4/CNTs on potential. (d) The stability test of Fe(a)@C-Fe3O4/CNTs for urea synthesis. Reproduced from Ref. [77] with permission of John Wiley and Sons Ltd.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr13.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Wireless, battery free, implantable bending sensing system based on flexible magnetic strips. Reproduced from Ref. [78] with permission of Elsevier. Wireless, battery free, implantable bending sensing system based on flexible magnetic strips. Reproduced from Ref. [78] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr14.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Schematic illustration of (A) the preparation of biofunctionalized porous Fe3O4 NPs and (B) the construction of a PEC biosensing platform for miRNA. Reproduced from Ref. [81] with permission of Elsevier. Schematic illustration of (A) the preparation of biofunctionalized porous Fe3O4 NPs and (B) the construction of a PEC biosensing platform for miRNA. Reproduced from Ref. [81] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr15.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Schematic illustration of the ECL biosensor construction process and 5hmC detection. Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier. Schematic illustration of the ECL biosensor construction process and 5hmC detection. Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr16.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Effect of different antibiotics and Cd2þ complex pollutants on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of rice seedling roots (A), stems (B) and leaves (C). Effect of ALV-J on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of chicken embryo fibroblast cell for 24, 48, 72h (D). Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier. Effect of different antibiotics and Cd2þ complex pollutants on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of rice seedling roots (A), stems (B) and leaves (C). Effect of ALV-J on 5hmC expression in the genomic DNA of chicken embryo fibroblast cell for 24, 48, 72h (D). Reproduced from Ref. [83] with permission of Elsevier.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr17.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Schematic illustration of synthesis of Fe3O4 NC/PAH/PSS/DOX hybrid nanostructures as theranostic agents for MRI and drug delivery. Reproduced from Ref. [89] with permission of Springer Nature. Schematic illustration of synthesis of Fe3O4 NC/PAH/PSS/DOX hybrid nanostructures as theranostic agents for MRI and drug delivery. Reproduced from Ref. [89] with permission of Springer Nature.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr18.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![In vivo MRI performance and tumor-targeting diagnosis ability of chiral Fe3O4 SPs. (A) T2WI images for the liver site of BALB/c mice before and after 30min tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, D-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1. (B) The statistical results of the contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the liver site of BALB/c mice, compared with the pre-injection group, after tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, DL-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1 for 30min. Tumor diagnosis resolution of chiral Fe3O4 SPs compared to Ferumoxytol in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice at the injection dose of 10mgkg−1, with (C) the T2WI images and (D) the statistic results of contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the 4T1 tumor site at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Broad tumor diagnosis by D-Fe3O4 SPs in (a) RM-1 tumor and (b) B16F10 tumor model mice, with (E) T2WI images and (F) the statistic contrast ratio at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Error bars are obtained from three parallel samples. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA. Reproduced from Ref. [90] with permission of John Wiley and Sons. In vivo MRI performance and tumor-targeting diagnosis ability of chiral Fe3O4 SPs. (A) T2WI images for the liver site of BALB/c mice before and after 30min tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, D-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1. (B) The statistical results of the contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the liver site of BALB/c mice, compared with the pre-injection group, after tail vein injection of D-Fe3O4 SPs, DL-Fe3O4 SPs, and L-Fe3O4 SPs at the dose of 1mgkg−1 for 30min. Tumor diagnosis resolution of chiral Fe3O4 SPs compared to Ferumoxytol in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice at the injection dose of 10mgkg−1, with (C) the T2WI images and (D) the statistic results of contrast ratio of the dotted circled region in the 4T1 tumor site at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Broad tumor diagnosis by D-Fe3O4 SPs in (a) RM-1 tumor and (b) B16F10 tumor model mice, with (E) T2WI images and (F) the statistic contrast ratio at 1h, 2h and 4h injection time. Error bars are obtained from three parallel samples. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA. Reproduced from Ref. [90] with permission of John Wiley and Sons.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr19.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Schematic illustration of Fe5C2@Fe3O4 NPs for pH-responsive Fe2+ release, ROS, and T2/T1 signal conversion. Reproduced from Ref. [91] with permission of American Chemical Society. Schematic illustration of Fe5C2@Fe3O4 NPs for pH-responsive Fe2+ release, ROS, and T2/T1 signal conversion. Reproduced from Ref. [91] with permission of American Chemical Society.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000004/v1_202508200524/S0366317525000342/v1_202508200524/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr20.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)