Introduction. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in hemodialysis (HD) patients is a major concern, but limited information exists on the HBV genotyping in patients on maintenance HD in Turkey.

Aim. To investigate the genotype and subgenotype distribution of HBV in Turkish HD patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Material and methods. A total of 248 HBsAg positive patients undergoing long-term HD from all regions of Turkey were included in this study. HBV genotypes were determined by phylogenetic analysis and by genotyping tools.

Results. HBV DNA was detected in 94/248 (38%) of the patients. Among the study patients, genotype D of HBV was predominant (99%) and one patient (1%) was infected with genotype G. The majority (82%) of HBV genotype D branched into subgenotype D1, and also in ayw2 HBsAg subtype clusters in the phylogenetic tree. However, 10% and 8% of the strains branched into subgenotype D2 (also in ayw3 HBsAg subtype cluster) and subgenotype D3 clusters, respectively.

Conclusion. In conclusion, HBV genotyping should be routinely applied to HD patients to establish a baseline. Determination of genotypes/subgenotypes of HBV may provide robust epidemiological data related to their circulation as well as their transmissibility.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) demonstrates significant genetic and geographical divergence. Genetic diversity of HBV is generated by lacking proofreading mechanism of reverse transcriptase enzyme. Eight genotypes (designed A to H) and about 25 subgenotypes have been currently described by divergence in the entire HBV genomic sequences. For genotypes, inter-group divergence is > 7.5% and for sub genotypes, inter-genotypic divergence is > 4% on the complete genome sequence, using phylogenetic analysis.1-3 However, based on the antigenic determinants of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HBV can be classified into nine serological types; adw2, adw4, adr, adrq-, ayw1, ayw2, ayw3, ayw4 and ayr.4 Different HBV genotypes show a distinct geographic distribution: genotype A is divided into A1, found in sub-Saharan Africa, A2, in Northern Europe, and A3 in Western Africa. Genotype B and C are predominant in Asia (B1 is found in Japan, B2-B5 are found in East Asia, B6 is found in the Arctic; C1, C2 and C3 are found in China, Korea, Southeast Asia, and in several South Pacific Island countries). Genotypes D1, D2, D3, D4, D5 and D7 are spread worldwide and associated particularly with Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean basin, North Africa, Russia, the Middle East, India, and across the Arctic. Genotype E is uniquely found in West Africa. Genotype F, divided into F1, F2, F3 and F4 subgenotypes, and genotype H are together found in the same geograpichal area; Alaska, Central and South America as well as in Polynesia.1,5,6 HBV genotypes have an original geographic distribution that is relatively well established. However, the origin of genotype G is unknwon.7 The existence of genotype G was first noted in 2000 and to date localized in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, France, Germany, Vietnam, Thailand, and Japan.8-15

Turkey is a country of intermediate/high HBV endemicity, with HBsAg prevalence in the general population ranging from 2.5% to 9.1% (higher in southeastern and eastern parts).16 The HBsAg positivity rate is 4.4% among chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients in Turkey.17 However, recently published reports indicate that Turkish HD patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection showed a very high HBsAg positivity rate (13.3%).18 Previous studies have demonstrated the dominance of genotype D in general patients with HBV infection as chronicled in Turkey.19-21 However, limited information exists on the HBV genotyping in patients on maintenance HD in Turkey. Genotypic variations in HBV are critical in the pathogenesis of liver disease and there are considered that the different genotypes may significantly differ in their responses to therapeutic intervention in CHB.22

AIMThe aim of the this study is to described the molecular epidemiology by phylogenetic analysis of HBV isolated from HD patients with CHB.

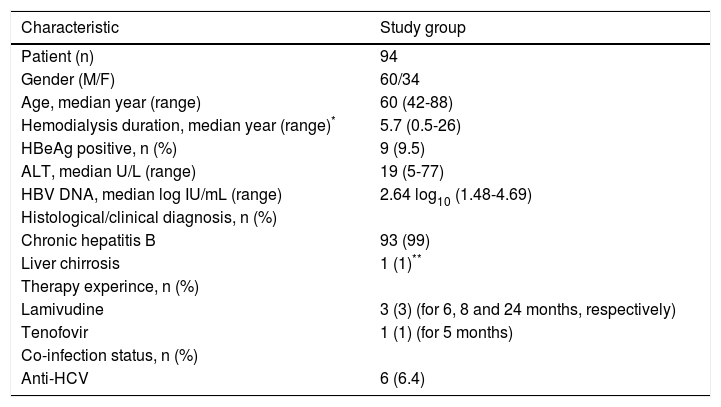

Material and MethodsPatientsThe number of chronic HD patients (including pediatric cases) according to general prevalence, at the end of 2009 is 48,433 in Turkey.20 A total of 248 HBsAg positive patients with end-stage renal diseases on long-term HD from all regions of Turkey were included in this study. Gender, age, hemodialysis duration, HBsAg positivity, alanine aminotransferase level, anti-HCV status and viral hepatitis risk factors of the patients were decision as to inclusion criteria of the study. The patients sera samples were obtained from Central Anatolia (n = 18), Aegean (n = 55), Marmara (n = 88), Blacksea (n = 9), Eastern Anatolia (n = 16), South-Eastern Anatolia (n = 25), and Mediterranean (n = 37) regions of Turkey, respectively. The patients were not intravenous drug users as previously and not renal transplantation history. The demographic, laboratory and clinical information statuses were provided by the clinical staff of the HD clinic. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. All of the patients were undergoing HD and categorized as HBV chronic carriers according to The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) clinical practice guidelines.23 Most of them were acquired of hepatitis B after initiation of hemodialysis. However, demographic and clinical features of the HD patients with HBV DNA positive shown in table 1. According to country legislation dedicated monitors must be used for HBsAg and anti-HCV “positive” patients. HBsAg positive patients must also be dialyzed in separate room. HD clinics which were included in the study, have to used the guideline (The Fresenius Medical Care Hygiene and Infection Control Guideline, NephroCare® C-CG-29-02 Rev. 01) for hygiene and infection control which provides state-of-the-art scientific knowlodge, technical information on infection control and hygiene issues and aims at supporting decision-making at the clinic level. However, the different protocol for use and decontamination, disinfection and sterilization of patient care items and instruments are available in HD clinics.

Demographic and clinical features of the hemodialysis patients with HBV DNA positive.

| Characteristic | Study group |

|---|---|

| Patient (n) | 94 |

| Gender (M/F) | 60/34 |

| Age, median year (range) | 60 (42-88) |

| Hemodialysis duration, median year (range)* | 5.7 (0.5-26) |

| HBeAg positive, n (%) | 9 (9.5) |

| ALT, median U/L (range) | 19 (5-77) |

| HBV DNA, median log IU/mL (range) | 2.64 log10 (1.48-4.69) |

| Histological/clinical diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Chronic hepatitis B | 93 (99) |

| Liver chirrosis | 1 (1)** |

| Therapy experince, n (%) | |

| Lamivudine | 3 (3) (for 6, 8 and 24 months, respectively) |

| Tenofovir | 1 (1) (for 5 months) |

| Co-infection status, n (%) | |

| Anti-HCV | 6 (6.4) |

HBV DNA was detected and quantified by a commercial PCR assay (artus HBV QS-RGQ test, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) on the real-time PCR platform (Rotor-Gene Q, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

HBV sequencingA pair of primers was designed:

- •

Forward:5’-TCGTGGTGGACTTCTCTCAATT-3’ and

- •

Reverse: 5’-CGTTGACAGACTTTCCAATCAAT-3’.

For amplification of the HBV pol gene region (in our clinical laboratory using pol gene sequencing for routine diagnosis of genotyping and drug resistance analysis to nucleos(t)ide analogue in HBV infection). The PCR conditions were applied as described previously.21

HBV genotypingGenotype and subgenotype of HBV was determined by phylogenetic analysis. The phlyogenetic analysis based to reverse transcriptase (codon; 43-344) and S gene (codon; 34-277) regions of HBV sequencing (768 bp). The nucleotide sequence was compared to those from the GenBank. Phylogenetic comparison was performed by Neighbor-Joining algoritm using the CLC Sequence Viewer 6.0.2 (CLC bio A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) software. However, HBV genotype and subgenotype was determined also by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTN program 2.2.25, blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)24 and by The Genafor/Arevir-Geno2pheno Drug Resistance Tool (www.coreceptor.bioinf.mpi-inf.mpg.de).

ResultsHBV DNA was detected in 94/248 (38%) of the patients. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the HBV DNA positive HD patients is shown in table 1.

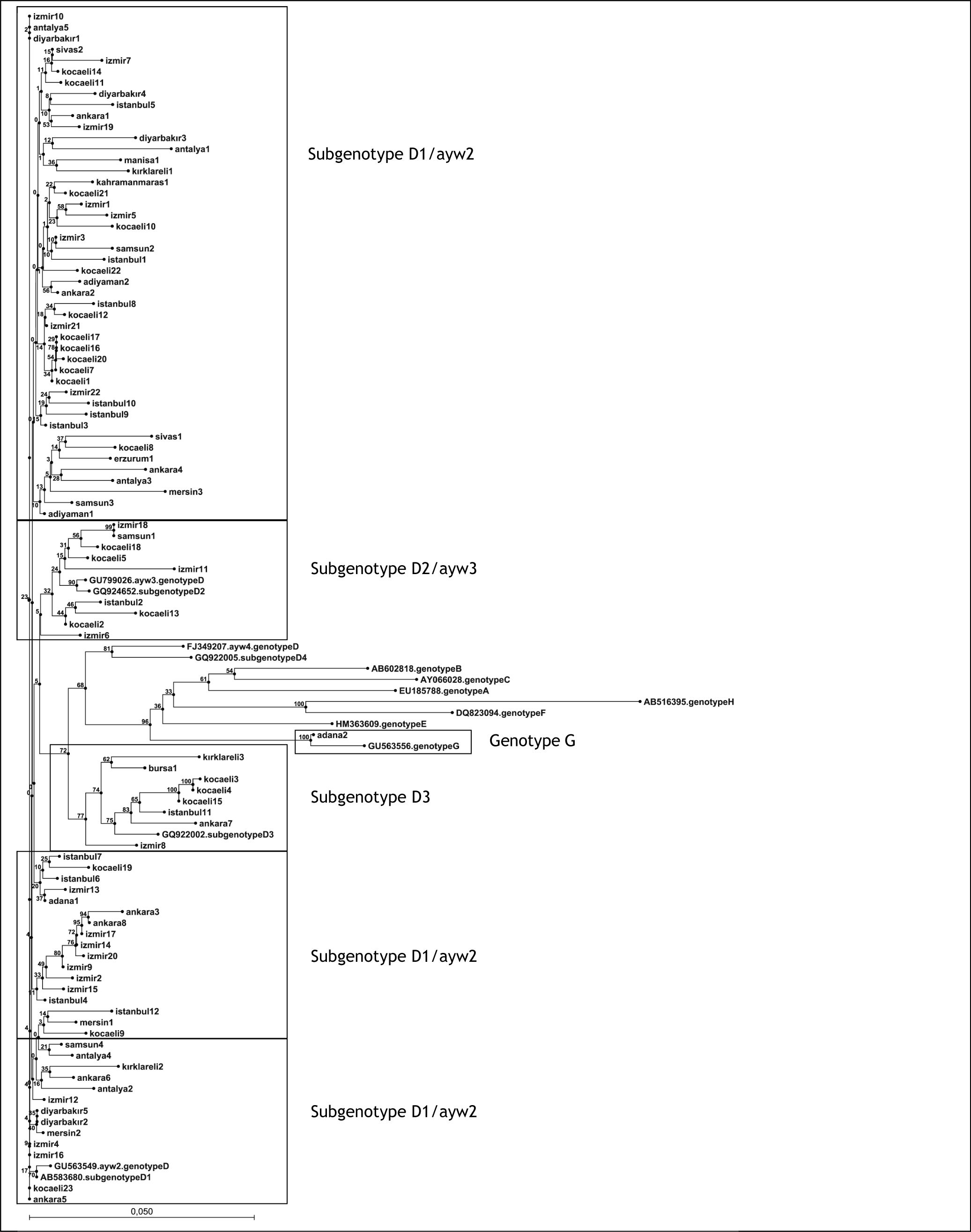

HBV genotype D (99%, 93/94) and genotype G (1%, 1/94) were detected in the phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1). The majority (82%, 76/93) of the HBV strains branched in subgenotype D1/ayw2 clusters in the phylogenetic tree. However, 10% (9/93) and 8% (8/93) of strains branched in subgenotype D2/ayw3 clusters and subgenotype D3 clusters, respectively (Figure 1).

Phylogenetic tree of hepatitis B virus (HBV) isolates obtained from hemodialysis patients. The phlyogenetic analysis based to reverse transcriptase (codon; 43-344) and S gene (codon; 34-277) regions of HBV sequences (768 bp). Neigbor-Joining analysis was carried out with other sequences from all HBV genotypes from GenBank using CLC Sequence Viewer 6.0 (CLC bio A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) software. Bootstrap support value (100 replicates) are shown at the respective branchers.

One patient infected with genotype G of HBV had been treated with HD three times per week for 4 years due to idiopathic end stage renal disease. Twelve years earlier, he had been diagnosed with brucellosis. During his brucellosis diagnosis, HBsAg positivity was detected. He was not an intravenous drug user as previously, and not any blood transfusion history. He had never traveled abroad. None of the people in his family had shown hepatitis B infection during examination. Notable however, the patient was not monogamous, and had multiple sexual partners.

DiscussionTo date, there is insufficient data on the molecular epidemiology of HBV in HD patients in Turkey. In the present study, phylogenetic analysis of HBV pol gene sequences isolated from Turkish HD patients revealed subgenotype D1/ayw2 constitutes the majority of the genotype D circulating in Turkey. Afterwards, strains of the other genotype D branched in subgenotype D2/ayw3 and subgenotype D3 clusters, respectively. In our recently published report, also based on the pol gene sequencing, HBV subgenotype D1 was predominant (84%) and subgenotypes D2, D3, and D4 were found in 10%, 5% and 0.2% of Turkish patients with CHB (n = 442) with normal renal function, respectively.25 According to the unique whole genome HBV sequence study, the chronic HBV carriers among the general population of Turkey had ayw2 (frequently) and ayw3 (rarely) HBsAg subtypes, respectively.19 These studies suggest the patients undergoing maintenance HD with normal renal function show approximately the same HBV subgenotypes and HBsAg subtypes distributed in Turkey. But, in limited studies D2 has been shown as the predominant subgenotype of HBV in Turkish patients.26-28 The similarity between these studies is the use of Pre-S gene amplification + restriction fragment length polymorphism techniques. However, in a study from the Southeastern part of Turkey with 132 CHB patients including HD patients, genotype D/ayw3 has been found in all serum samples by sequencing of the amplified S gene region after seminested PCR protocol.29 This discrepancy is probably due to the methodology. Interestingly, HBV genotyping studies in HD patients are limited throughout the world. In a study from Indonesia, including patients on HD, it has been reported that all HBV isolates belonged to genotype B, with more than 90% of them being classified into HBsAg subtype adw.30 In another study, during nosocomial infections in two Brazilian HD centers including 27 HD patients, HBV strains were genotyped. In an HD unit in Rio de Janeiro, 14 HBV isolates were classified into two different genotyped and five different subgenotyped: D3, D4, A1, A2, and A3. In another HD unit in the state of Sao Paulo, where an outbreak of HBV infection occurred in 1996-1997, genotyping analysis showed that all 13 patients were infected with HBV isolates of genotype D. Co-infection with strain A1 was detected in seven of them.31

This study revealed an exotic HBV genotype; genotype G. Genotype G of HBV has not been reported to date in Turkey. This genotype is the most uncommon of all HBV genotypes. It is essentially identical to the other HBV genotypes, but has some uniqe features including a 36-bp insertion downstream of the core gene start codon.8 However, epidemiological and clinical information on genotype G infection is limited, likely due to the low prevalence throughout the world.32 HBV genotype G co-infection with HIV has been described and reported from Brazil, Mexico, Germany, France, Japan and the USA.9-11,13,15 Probably the genotype G of HBV strains could be acquired via sexual transmission. The unique patient infected with genotype G of this study is an adult and his promiscuous sexual behaviour may be defined as a risk factor for transmission of this genotype. But, there is insufficient information related to sexual transmission of HBV genotype G and an association with HIV.

Genotyping and HBsAg subtyping of HBV isolates are useful tools to understand the epidemiology of HBV infection.3,6 However, their clinical significance is yet to be fully defined. Studies have demonstrated associations between genotype and subgenotypes and disease severity and treatment outcomes of HBV infection.22 But, the distribution of HBV genotypes/subgenotypes in dialysis patients is not adequately revealed.33 The revealing of HBV genotypes/subgenotypes may help in determining disease burden in HD patients or within dialysis units. Newly recognized HBV infection post renal transplantation can reflect de novo infection or reactivation of prior resolved infection.34 Therefore, baseline HBV genotyping may be required in renal transplant recipients such as HD patients on discrimination of HBV infection status. According to the recently published review, determination of HBV genotype should form part of the management protocol in treating CHB.35 However, the major guidelines for the management of CHB published by EASL, the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)25,36,37 suggest that genotyping of HBV is not recommended as part of the management of CHB.

In conclusion, our study suggests that genotype D of HBV is dominant (D1 is more frequent) and genotype G also present and HBsAg subtype ayw is dominant (ayw2 is more frequent) but ayw3 HBsAg subtype is also present in HD patients in Turkey. However, the determination of genotypes/ subgenotypes of HBV may provide robust epidemiological data related to their circulation and transmissibility.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FundingThe authors declare no funding

Ethical ApprovalThe ethical approval is required; Kocaeli University, Clinical Research Ethics Committee: Project number; KKAEK 2009/24. Date; 24.11.2009, Approving number; 5/16.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Prof. Dr. Tevfik Ecder from Diaverium Turkey for helping us in providing patient samples.