Alcohol metabolism is a complex process with large individual variations related to absorption, distribution and elimination. Among the multiple factors which influence these variations, genetic factors especially those related to the different alleles of ADH2 and ALDH2, are the most well known and are related to the development of alcohol dependence, particularly in some populations such as those of Asian origin. The importance of new polymorphisms such as those in the ALDH promotor region requires further study. Furthermore, the importance of other factors such as nutrition and gastric metabolism should be taken into account to explain the variations in ethanol metabolism. The metabolic alterations produced by alcohol in the liver are responsible for liver damage. The individual variations in the metabolism of alcohol are responsible for the different toxicity of alcohol in both the liver and other organs.

In most countries chronic alcohol consumption is a medical problem of great magnitude with important socio-economic repercussions.1 Liver cirrhosis is one of the first causes of death among middle-aged subjects, especially males, and, in several populations studied, the evolution of the rate of mortality by cirrhosis is parallel to the rate of alcohol intake.2 Apart from the liver involvement, alcohol often causes neurologic, cardiac, muscular and pancreatic disease as well as a greater incidence of neoplasms in the digestive and respiratory tracts.

The toxic effects of alcohol are directly related to the plasma levels achieved after alcohol intake. Three aspects should be taken into account on studying the pharmacokinetics of alcohol: its absorption in the stomach and the small intestine, its distribution throughout the organism and its elimination or metabolism. Practically all the alcohol absorbed is metabolized in the liver where it undergoes two oxidative processes during which it is first converted into acetaldehyde, its toxic metabolite, and afterwards, into acetate.3,4 As a consequence of the hepatic metabolism of alcohol a series of metabolic alterations take place which are responsible for liver damage.3 In addition, there are many factors which may influence alcohol metabolism and, consequently, modulate its toxic effect.5,6

The present review analyses the hepatic metabolism of alcohol, the metabolic changes produced in the liver during alcohol metabolism and their relationship with the pathogenesis of the disease and, finally, the different factors which may influence alcohol metabolism.

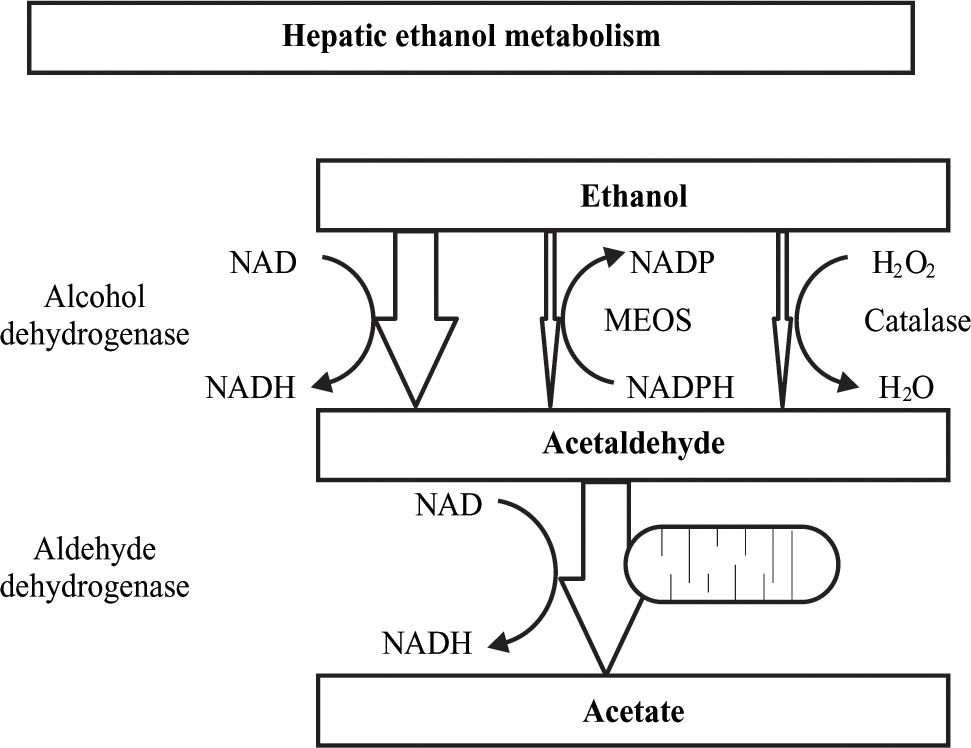

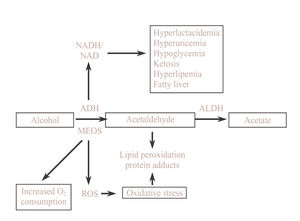

Alcohol metabolismIn the hepatocyte there are three systems which are able to metabolize ethanol and these are located in three different cellular compartments: alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) located in the cytosol, the microsomal ethanol oxidazing system (MEOS) situated in the endoplasmic reticulum and catalase located in the peroxisomes. Each of these systems causes specific metabolic and toxic alterations which all lead to acetaldehyde production, being acetaldehyde the toxic metabolite of ethanol. In the second oxidative step, acetaldehyde is quickly metabolized to acetate by mitochondrial acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) action. Finally, the acetate produced in the liver is released into the blood and is oxidized by peripheral tissues to carbon dioxide, fatty acids and water4(Figure 1).

Alcohol dehydrogenase systemGenetic polymorphism of ADHHuman ADH is a dimeric zinc dependent methaloenzyme for which five different classes, encoded in seven genes, from ADH1 to ADH7, have been described.7 However, the isoenzymes, which are important for the alcohol metabolism are of the classes I, II and IV. Class I isoenzymes have a low Km for ethanol, are found in the liver and consist of homo or heterodimeric forms of three subunits: α, β, and γ, ADH1, ADH2 and ADH3, respectively. Class II ADH is a homodimeric π π form, ADH4, with a relatively high Km for ethanol (34 mM) and is found in the liver. The class IV isoenzyme, ADH7, is a homodimeric oo found in the stomach and has a very high Km for ethanol. The class III isoenzyme (χADH), ADH5, has a very low affinity for ethanol and therefore, does not participate in its oxidation in the liver. Finally, the recently described class V isoenzyme, ADH6, is found in both the stomach and the liver.

There are genetic variations for ADH2 and ADH3 encoded by different alleles. Alleles ADH2*1, ADH2*2 and ADH2*3 have subunits β1, β2 and β3 respectively. Alleles ADH3*1 and ADH3*2 have subunits Y1 and Y2, respectively. The frequency of the different ADH alleles has ethnic variations. Thus, the ADH2*1 allele predominates in black and white races, the ADH2*2 allele in oriental subjects and the distribution of ADH2*3 is found in about of 25% of black subjects. With regard to the ADH3 polymorphism, ADH3*1 and ADH3*2 appear with about equal frequency among Caucasian subjects while the ADH3*1 allele predominates among black and oriental races. The affinity for alcohol and the metabolic rate among the different isoenzymes differ, and, as will be shown later, these genetic differences have been implicated in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease.

Influence of the genetic ADH polymorphism in alcohol metabolism8,9Several studies have attempted to relate the genetic polymorphism of ADH to alcohol dependence. In Asian population alcoholics were found to present a lower prevalence of the ADH2*2 and ADH3*1 isoenzymes which have the subunits β2 β2 and γ1 γ1 which oxidize alcohol the most rapidly, producing a greater concentration of acetaldehyde which in turn, produces an uncomfortable sensation with facial flushing and tachycardia.10 Other studies did not find any differences in relation to ADH3 in Asian subjects.11 On the other and, the same population of individuals with these isoenzymes would have a greater risk of developing organic lesions, especially hepatic,12 The relationship between the ADH isoenzymes, alcohol metabolism and liver damage in the European population is not as clear, possibly due to the low prevalence of the ADH2*2 isoenzyme in Caucasians.13 Only a recently published multicenter study showed a lower frequency of ADH2*2 in alcoholics than in non alcoholic individuals including healthy controls and patients with cirrhosis of viral etiology. In this study an association was also found between the ADH2*2 and ADH3*1 alleles reflecting a linkage disequilibrium between both genes.14 In this study the distribution of ADH3 alleles was also homogeneous among the different European populations, with no differences among controls, alcoholics with normal liver and alcoholics with cirrhosis, suggesting that ADH3 does not play a causative role in the development of alcohol-induced cirrhosis as previously reported.15 Moreover, the influence of ADH3 polymorphism on predisposition to alcohol abuse was small in agreement with other European studies.16 In a study carried out by our Unit including a population of 327 chronic alcoholics, no differences were observed in regard to the prevalence of the ADH2 and ADH3 isoenzymes between alcoholics and controls or between alcoholics in relation to the presence and severity of the liver lesions.17

Contrary to what was expected, no differences were found in relation to the alcohol elimination rate among the individuals with the ADH2*1 allele and with the ADH2*2 allele.18 And thus, the mechanism of the protector effect of the ADH2*2 allele remains unclear. Since the gene of the ADH2 is expressed in many tissues, including the blood vessels,19 it has been suggested that the greater extraheptic metabolism of alcohol in individuals with the ADH2*2 allele, although small in relation to hepatic metabolism, may explain the uncomfortable cutaneous effects, and thus, the protector effect on alcohol dependence.

Gastric ADHIn the human stomach the presence of class I, III and IV ADH isoenzymes of both low and high Km for ethanol has been demonstrated.20-22 The serum levels of alcohol are significantly lower when alcohol is administered orally than when the same amount is given intravenously. This difference is known as first pass metabolism (FPM) of alcohol. It was initially believed that similar to what happens with other substances, the FPM was of hepatic origin. Posterior studies in experimental animals and in man have shown that the stomach plays a fundamental role in FPM.23 To this effect, the gastric mucosa has been shown to have ADH isoenzymes such as σ ADH which are able to metabolize alcohol at the high concentrations observed at this level after ingestion and that FPM completely disappears in patient undergoing gastrectomy, when the gastric emptying is accelerated or when alcohol is administered directly to the duodenum.24

Gastric ADH is responsible for some of the ethnic and gender variations observed in alcohol metabolism which may favor its toxicity. The o ADH is present in most Caucasian subjects while in most Asians its activity is very low or undetectable, making the FPM very reduced in this population group.25

Marked differences have also been reported in relation to gender. To this effect, when the same dose of alcohol is administered intravenously, the serum concentrations are similar in both males and females. To the contrary, when the same dose is administered orally, the serum alcohol levels are significantly greater in women than in men, although these differences disappear after the age of 50 years.26 This lower FPM in women is related to their lower gastric ADH activity, especially of the class III isoenzyme.27 In addition, the differences in FPM between women and men are exacerbated in chronic alcoholism and, in alcoholic women, for the same dose of alcohol blood levels were the same, whether given intravenously or orally. Thus, alcoholic women have a total loss of the gastric protective barrier provided by the FPM.28 This fact may be one of the factors which contributes to the greater susceptibility of women to the toxic effects of alcohol.

The importance of the gastric metabolism of alcohol is also supported by the fact that commonly used drugs such a aspirin and some H2 receptor antagonists of histamine reduce the activity of gastric ADH and/or accelerate gastric emptying and, consequently, decrease FPM increasing the serum concentrations of alcohol and favoring its toxic effects.29-31 These effects are more evident after the consumption of moderate doses of alcohol.

Role of bacterial and colonic ADH in alcohol metabolismADH can be detected both in human and rat colon mucosa.32 Moreover, many colonic bacteria representing the normal human flora may possess high ADH activity and produce acetaldehyde from ethanol.33 Thus, it has been suggested that there is a bacteriocolonic pathway for ethanol oxidation. In this pathway ethanol is oxidized by bacterial ADH to acetaldehyde. Then acetaldehyde is oxidized by colonic mucosa or bacterial ALDH to acetate.34 Part of the intracolonic acetaldehyde is absorbed to the portal vein and oxidized in the liver. The ALDH activity of colonic mucosa is low and during ethanol oxidation acetaldehyde accumulates in the colon, being one of the factors related to the pathogenesis of alcohol-related gastrointestinal symptoms and diseases.34 However, the contribution of the bacteriocolonic pathways to extrahepatic ethanol metabolism remains to be established.

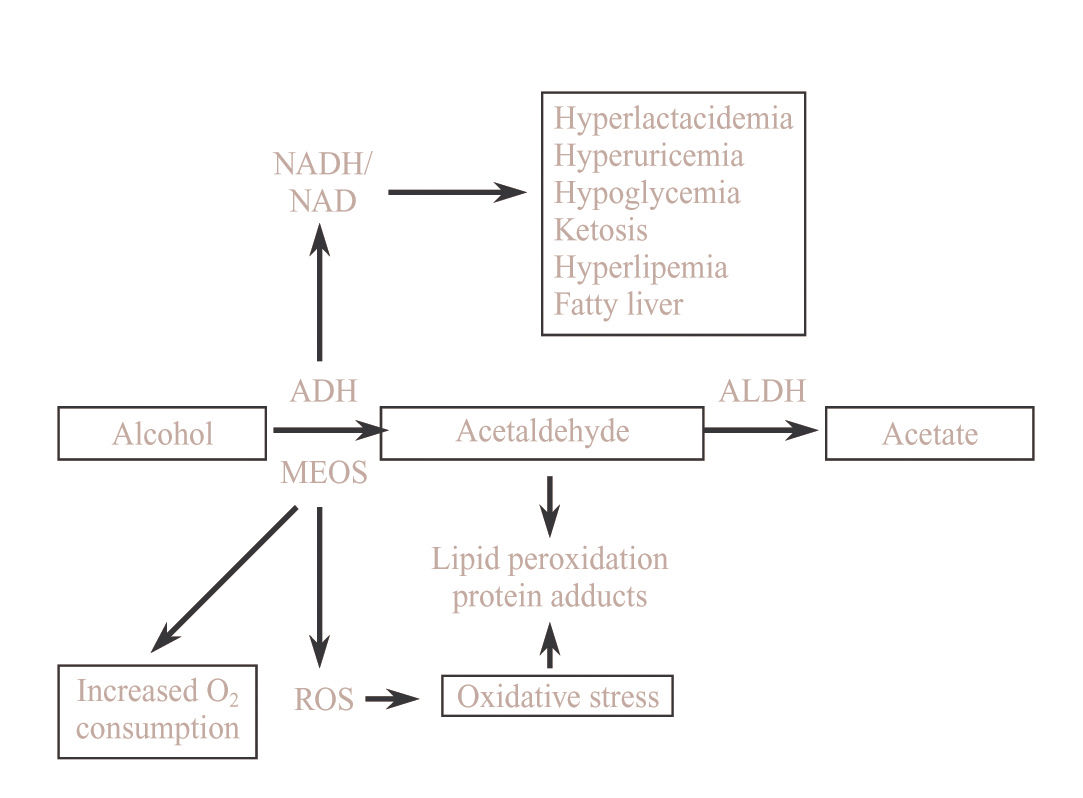

Metabolic changes related to ethanol oxidation by ADHDuring ethanol oxidation mediated by ADH, hydrogen is transferred from the substrate to the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), converting it to its reduced form (NADH). The excess of reduced equivalents, mainly NADH, produces a change in the redox system of the cytosol which is demonstrated by a change in the lactate pyruvate ratio. This redox imbalance is responsible for a series of metabolic alterations which favor liver damage. Hyperlact-acidemia contributes to acidosis and reduces the capacity of the kidney to excrete uric acid leading to hyperuricemia.

The increase in the NADH/NAD ratio raises the a-glycerophosphate concentrations which favor the deposits of triglycerides in the liver. Moreover, the excess of NADH favors the synthesis of fatty acids. There is also a reduction in the activity of the citric acid cycle. The mechanism by which fatty acids are accumulated in the liver in the form of triglycerides is complex and is related to different metabolic alterations such as increase in hepatic synthesis, a decrease in hepatic lipoprotein secretion, a greater mobilization of fatty acids from adipose tissue favoring their hepatic uptake and a decrease in fatty acid oxidation.35

In subjects with a depletion in glycogen deposits or who have pre-existing abnormalities in carbohydrate metabolism, alcohol intoxication may be cause of severe hypoglycemia due, at least in part, to a blockade of neo-glucogenesis by the increase in the NADH/NAD ratio. On other situations alcohol may favor rather than inhibit neoglucogenesis and alcoholism may, therefore, be cause of hyperglycemia35(Figure 2).

Microsomal ethanol oxidazing system (MEOS)The microsomal ethanol oxidazing system (MEOS) constitutes a second mechanism that is able to oxidize alcohol. The MEOS shares many properties with other microsomal drug metabolizing enzymes such as utilization the cytochrome P-450, NADPH and oxygen.36 In addition, an increase in MEOS activity is produced as a consequence of chronic alcohol consumption and this affects the CYP2E1 which is the ethanol inducible fraction of the cytochrome P-450 and is also capable of activating other hepatotoxic agents.37 The Km of MEOS is relatively high in relation to that of ADH making ADH the most important mechanism in the presence of low concentrations of alcohol. To the contrary, at high concentrations of alcohol and in chronic alcoholism, the importance of MEOS is increased, especially in reference to its capacity to be induced, contrasting with ADH which is not inducible.

Different polymorphisms of the humans CYP2E1 gene have been reported, particularly in the 5’-flanking38 region and some authors have attempted to related these polymorphisms to a greater susceptibility to develop liver lesions. However, to date the results of the different studies have been negative or inconclusive.40,41 Neither did we find any relationship between the c1/c1 polymorphism of the CYP2E1 and chronic alcoholism or liver damage.17

Consequences of alcohol oxidation by MEOS and its inductionThe CYP2E1 has a relatively high redox potential which, on using NADP as a cofactor, leads to the formation of free oxygen radical, oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation42(Figure 2). Oxidative stress induces the activation of Kupffer cells, increasing the expression of several cytokines such as transforming growth factor beta, tumoral necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1. All of this mechanisms contributes to the activation of stellate cells with the consequent increase in collagen synthesis favoring the progression of alcoholic liver disease.43

Interaction between alcohol and the metabolism of other drugsAcute alcohol inhibits the metabolism of other drugs. The main mechanism is a competitive inhibition for the binding of both substances with cytochrome P-450. Other mechanisms may be the release of steroid hormones which may inhibit some microsomal enzymes and an inhibition of the activity of the citric acid cycle due to the excess production of NADH. This competitive inhibition may occur with high or low levels of ethanol, depending on the drug.44

In addition to tolerance to alcohol, chronic alcoholics develop tolerance to different drugs. This fact that was initially attributed to an adaptation of the central nervous system is due, at least in part, to metabolic adaptation. To this effect, an increase in the plasma clearance of many drugs of up to 50% has been observed.45 This increase in plasma drug clearance may be due to the induction of the microsomal enzymes, which metabolize the drugs, and a greater content of cytochrome P-450. These effects of chronic alcohol intake may be partially modulated by diet and the influence of carbohydrate,46 lipid47 and protein48 content has been demonstrated in animal models. This metabolic tolerance may persist for days or even weeks after cessation of alcohol intake and this should be taken into account when establishing the dosage of some drugs.

The induction of cytochrome P-4502E1 does not only influence the oxidation of ethanol but is also capable of converting many xenobiotics into their toxic metabolites, increasing the vulnerability of chronic alcoholics.44 Among other substances, some industrial solvents such as bromobenze or vinyl chloride, anesthetics, cocaine, medications of common use such as isoniazid, phenylbutazone and analgesics such as paracetamol are substrates for cytochrome P4502E1 and, thus, affected by alcohol consumption.49 Usual doses of paracetamol (2 to 4 g/day) may cause severe hepatitis in alcoholics, especially in the first days of abstinence when the microsomal system remains induced and the competitive effect of alcohol is lacking.50

There appears to be an association between chronic alcohol consumption and the incidence of neoplasms, especially of the digestive and respiratory tract.51 One of the mechanisms may be the effect of alcohol on enzymatic systems depending on cytochrome P-450 which are capable of activating carciogens.49,51 Another mechanism may be a synergistic effect between alcohol and smoking since most alcoholics are smokers.52 Another factor which may contribute may be a deficit in vitamin A.53 Alcoholics have a greater microsomal degradation of vitamin A which is necessary to maintain mucosal integrity and avoid the activation of carciogens. However, the administration of supplements of vitamin A or beta carotenes should be carefully undertaken since alcohol potentiates their hepatoxicity.

CatalaseCatalase is capable of oxidizing ethanol in vitro in the presence of a generating system of hydrogen peroxide. However, in physiological conditions, catalase plays a very small role in alcohol metabolism.4

These effect of catalase could be greater if an important amount of hydrogen peroxide were produced from Oxidation of the fatty acids in the peroxisomes.54 However, the rate of alcohol metabolism is reduced by adding fatty acids and the β-oxidation of fatty acids is inhibited by the NADH generated during alcohol metabolism by ADH. Likewise, the reduced equivalents generated during alcohol oxidation by ADH inhibit the production of hydrogen peroxide leading to significantly diminished rates of peroxidation of alcohols via catalase.55 Other studies have confirmed that oxidation of the fatty acids in the peroxisomes is of little importance in alcohol metabolism. Finally, the scarce role of catalase in alcohol metabolism has been demonstrated by the practically lack of effect of the administration of the catalase inhibitor aminotriazol on alcohol metabolism.56 In chronic alcoholics catalase may contribute to the oxidation of fatty acids compensating, in part, the lower oxidation due to mitochondrial damage.

Non oxidative metabolism of alcoholLaposata and Lange described a non oxidative metabolism of alcohol which is capable of forming ethyl esters from the fatty acids.57 On comparing subjects with acute alcohol intoxication with control subjects, these authors found a significantly high concentration of fatty acid ethyl esters in different organs such as the pancreas, liver, heart and adipose tissue which are organs in which alcohol induced lesions are often present and some of which also lack an oxidative system to metabolize alcohol. Thus, fatty acid ethyl esters may play a role in the pathogenesis of the lesions induced by alcohol consumption, although studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Acetaldehyde metabolismAldehyde dehydrogenaseAcetaldehyde is rapidly metabolized to acetate by the action of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). There are two classes of ALDH, ALDH1 located in the cytosol with a high Km for acetaldehyde and ALDH2 or mitochondrial ALDH with a low Km for acetaldehyde which is the class of the greatest importance in the metabolism of acetaldehyde. ALDH2 also presents a genetic polymorphism with two alleles, ALDH2*1 and ALDH2*2, with there also being homo and heteroxygotes for each. ALDH2*2 is a physiologically inactive form.56 A recent study has shown that the administration o a dose of ethanol produces an area under the curve (AUC) for plasma concentrations of alcohol 2-3-fold greater in the ALDH2*2 homozygotes than in the ALDH2*1 homozygotes while the AUC for acetaldehyde in the ALDH2*2 homozygotes was 220-fold and 5-fold greater than in the ALDH2*1 homozygotes and heterozygotes, respectively.58 The slower elimination of alcohol in subjects with the ALDH2*2 genotype is due to the inhibition of ADH activity by the accumulated acetaldehyde. These data suggest that in ALDH2*1 homozygotic subject, mitochondrial ALDH is sufficient to oxidate all the acetaldehyde produced by ADH, and that there is possibly enough mitochondrial ALDH in the heterozygotes to metabolize the acetaldehyde,59 although more slowly, while the cytosolic ADLH1 is responsible for the oxidation of acetaldehyde in the ALDH2 homozygotes in which practically no mitochondrial ALDH activity is detected.60

The prevalence of the different ALDH genotypes varies according to the populations studied so that in Caucasian subjects the ALDH2*2 genotype is not detected while its prevalence is high among Asians, ranging from 10% to 44% of the population.59,61

The elevated levels of acetaldehyde achieved in ALDH2*2 homozygotic subjects, even after the ingestion of a small or moderate amount of alcohol, produce circulatory changes which may be translated into a reaction of discomfort with tachycardia and facial flushing. All of this leads to aversion to alcohol and has a protector effect versus alcohol dependence in Orientals in which the prevalence of the ALDH2*2 genotype is much lower in alcoholics than in the general population.62 In recent years a trend towards an increase in the prevalence of ALDH2*2 heterozygotes has been observed among oriental alcoholic subject. This indicates that the protection versus alcohol dependence in heterozygotes is not complete and environmental and sociocultural factors also influence in these subjects.5

A new polymorphism has recently been described in the promotor region of the ALDH2. This polymorphism is an A/G mutation which is less active in the A than in the G allele and it has been detected with variable frequency in different population groups, including Caucasians.63 In a study carried out in a Japanese group, no significant differences were found between the A/G allelic frequency among chronic alcoholics and the control population.64

In our group of chronic alcoholics we have also investigated the ALDH2 polymorphism as well as the mutation in the promotor region. Similar to other Caucasian population studied we did not detect the ALDH2*2 genotype. In regard to the promotor polymorphism, the A allele frequency was similar in chronic alcoholics (15%) and controls (23%). Neither did we detect significant differences between alcoholics with or without liver lesions, or between those with initial lesions or cirrhosis.17 Nevertheless, further studies are required to elucidate the possible influence of the A/G polymorphism of the promotor as well as other possible polymorphisms in this region in the metabolism of alcohol and, thus, in alcohol dependence.

Metabolic alterations produced by acetaldehyde and acetateThe metabolites of ethanol, acetaldehyde and, to a lesser extent, acetate, are responsible for most of the metabolic effects of ethanol, not only in the liver but also in other organs such as the heart and blood vessels, adipose tissue and the brain.65

In the liver, acetaldehyde produces an increase in lipid peroxidation thereby causing oxidative stress.66,67 Acetaldehyde binds to proteins of the different cellular membranes, particularly in chronic alcoholics, leading to the formation of acetaldehyde-protein complexes which are responsible for the appearance of antibodies versus these complexes (Figure 2). The appearance of circulating antibodies is related to the degree of liver lesion and is also observed in liver diseases of non alcoholic etiology, with the imunocomplexes which are formed being one of the immunologic mechanisms which may contribute to the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease.68

As previously mentioned, the ALDH responsible for the metabolism of acetaldehyde is mitochondrial and, moreover, the reoxidation of the NADH cofactor to NAD also depends on mitochondrial integrity. Acetaldehyde diminishes the capacity of the mitochondria to oxidize fatty acid as well as other functions. This mitochondrial dysfunction leads to higher levels of acetaldehyde in the plasma causing a vicious circle which thereby contributes to the progression of liver damage.69

Factors influencing alcohol and acetaldehyde metabolismThe plasma concentration of ethanol, and thus, its toxicity, depends on the absorption of alcohol in the upper gastrointestinal tract, its distribution throughout the organism and its hepatic metabolism. All these steps may be influenced by genetic and environmental factors.

Gastric emptying and ethanol absorption depend on the concentration of alcohol in the drinking beverage, the speed with which it is drunk and whether the alcohol is taken while fasting or with a meal.70 Some studies have demonstrated that food increases the ethanol elimination rate by around 50% and this effect is similar in men and women and it is independent of the composition of the meal.6 Apart from the effect on first pass metabolism, the effect of food may be related to an increase in hepatic blood flow, the activation of enzymes or the capacity of the reoxidation of NADH. Likewise, as indicated, first pass metabolism is due to the action of gastric ADH which is adequate to oxidate alcohol at the high concentrations achieved in the stomach. First pass metabolism is reduced in Asian subjects, in women and in cirrhotic alcoholics. In all these situations there is lesser activity, whether genetic or acquired of ADH, especially with regard to the isoenzymes of high Km for ethanol such as σ and χ ADH. Gastric ADH activity and thus, first pass metabolism are also affected by other drugs.

Alcohol is homogeneously distributed throughout body water. The plasma concentration of alcohol depends on weight and the amount of body water.71 Thus, the volume of distribution of alcohol is, in general, lower in women than in men and this factor, together with the lower first pass metabolism contributes to the greater susceptibility of women to the toxic effect of alcohol.

Different factors influence the hepatic metabolism of alcohol and acetaldehyde. Among these, environmental and genetic factors, chronic alcohol intake and the liver disease itself should be considered.

Genetic and environmental factorsAs indicated in the corresponding section, the genetic variations of the main enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism, cytosolic ADH and mitochondrial ALDH, greatly influence alcohol metabolism and the different prevalence of the different isoenzymes explains the greater or lesser susceptibility of developing an alcohol dependence syndrome according to the population studied. To the contrary, the genetic polymorphism of the CYP2E1 does not appear to be of great importance in the greater or lesser susceptibility of liver damage produced by alcohol.

Alcohol metabolism may be influenced by the nutritional state since malnutrition diminishes ADH activity, similar to what occurs with high concentrations of alcohol.72 Changes have been described in the metabolism of alcohol related to hepatic flow73 and circadian rhythm.74 The effect of different drugs on alcohol metabolism is of little importance and only fructose has been found to significantly increase alcohol metabolism.75

Influence of chronic alcohol consumptionChronic alcoholics show greater tolerance to alcohol. This is due to an adaptation of the central nervous system, but also to an increase in the ethanol elimination rate or metabolic tolerance.76 The mechanisms for the increased ethanol metabolic rate observed in chronic alcoholics are not completely known and this phenomenon has been attributed to increased ADH activity, to increased mitochondrial reoxidation of NADH, to a hypermetabolic state in the liver, to increased microsomal oxidation and to catalase.3

Most studies have shown that chronic alcohol intake does not increase ADH activity but rather, may be diminished even in the absence of liver involvement.77 Ethanol induces an increase of Na, K, ATPase, followed by enhanced ATP consumption, increased oxygen consumption, and increased mitochondrial NADH reoxidation providing the basis for the hypermetabolic state of the liver, which has been suggested as responsible for the adaptative increase in ethanol elimination.78 However, this findings have not been confirmed by other studies.79

In both experimental models and in humans, MEOS activity has been found to be increased in chronic alcoholism, with this probably being the mechanism of the increase in the ethanol elimination rate. Moreover, in human studies it has been found that alcohol consumption produces an increase in the ethanol elimination rate, specially at high concentrations, which is when the action of MEOS take place.37 This is important since it leads to a greater plasma concentration of acetaldehyde as well as an increase in toxic metabolites which may cause liver damage.

The increase in the ethanol oxidation rate in chronic alcoholics results in increases of both blood and tissue acetaldehyde concentrations. In this regard, we have reported that in chronic alcoholics blood acetaldehyde level correlated with the rates of ethanol elimination.77 Chronic alcohol consumption also produces a significant reduction in the mitochondrial capacity to oxidize acetaldehyde.69 This is due to a lower capacity of the mitochondria to reoxidize NADH and possibly to a lower mitochondrial ALDH activity.80

During ethanol oxidation blood acetate levels are also higher in alcoholics than in controls, and there is a high significant positive correlation between blood acetate concentration and the rate of ethanol elimination in chronic alcoholics. Thus, increased blood levels of acetate in the presence of ethanol indicate metabolic tolerance to alcohol and has been proposed as a laboratory marker of alcoholism.81

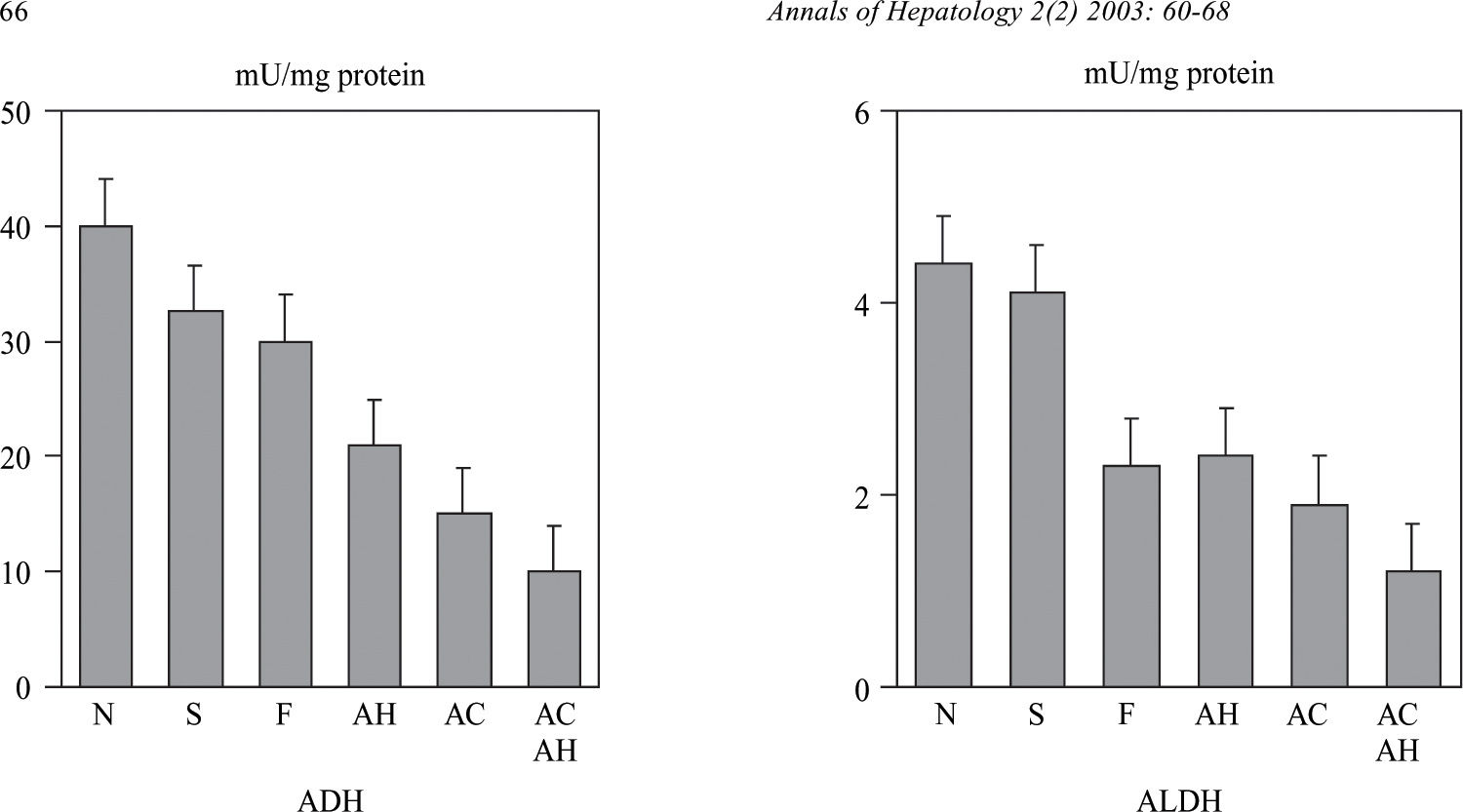

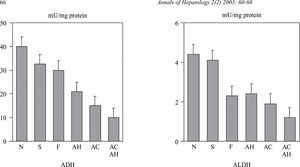

Influence of liver lesionsLiver involvement is one of the factors which may influence in alcohol metabolism. To this effect, the adaptative increase in alcohol metabolism observed in chronic alcoholics disappears in patients with advanced liver disease. In a study carried out in our Liver Unit we determined the hepatic activity of a low and high Km ADH and ALDH in a series of chronic alcoholics with different degree of liver involvement, from normal liver to cirrhosis. In this study, a decrease was observed in both ADH and mitochondrial ALDH activity which was proportional to the severity of the liver lesions82(Figure 3). The activity of these two enzymes also correlated with the values of serum bilirubin, albumin and prothrombin index. These results have been confirmed by other authors and indicate that the decrease in ADH and ALDH activity in chronic alcoholics is not a primary defect in these patients, but rather, is secondary to liver lesion. A decrease in the hepatic activity of mitochondrial ALDH was also observed in this study in patients with liver damage of non alcoholic etiology.82 This fact may explain the increase in the levels of acetaldehyde of endogenous origin83 as well as the presence of antibodies versus the acetaldehyde-protein complexes described in patients with non alcoholic liver disease.84 This difficulty in metabolizing acetaldehyde may justify the recommendation of avoiding alcohol intake in patients with non alcoholic liver disease.

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and low Km acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in alcoholic patients with different degree of liver damage: N: normal liver; S: steatosis; F: fibrosis; AH: alcoholic hepatitis; AC: alcoholic cirrhosis; ACAH: alcoholic cirrhosis with associated alcoholic hepatitis. (from Panés et al, ref. 82).

The research work of the authors was supported in part by a grant from Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (FIS 98/1082).