Tolloid like protein 1 (TLL1) rs17047200 has been reported to be associated with HCC development and liver fibrosis. However, to our knowledge, no studies have been performed on Latin Americans and comparative differences between TLL1 rs17047200 in HCC patients from Latin America and Europe are undefined.

Materials and MethodsCross-sectional analysis was performed on Latin American and European individuals. We analyzed TLL1 rs17047200 on DNA from 1194 individuals, including 420 patients with HCC (86.0 % cirrhotics) and 774 without HCC (65.9 % cirrhotics).

ResultsTLL1 rs17047200 genotype AT/TT was not associated with HCC development in Latin Americans (OR: 0.699, 95 %CI 0.456-1.072, p = 0.101) or Europeans (OR: 0.736, 95 %CI 0.447-1.211, p = 0.228). TLL1 AT/TT was not correlated with fibrosis stages among metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) patients from Latin America (OR: 0.975, 95 %CI 0.496-1.918, p = 0.941). Among Europeans, alcohol-related HCC had lower TLL1 AT/TT frequencies than cirrhosis (18.3 % versus 42.3 %, OR: 0.273, 95 %CI 0.096-0.773, p = 0.015).

ConclusionsWe found no evidence that the TLL1 rs17047200 AT/TT genotype is a risk factor for HCC development in Latin Americans or Europeans. A larger study integrating ethnic and etiology backgrounds is needed to determine the importance of the TLL1 SNP in HCC development.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the primary malignancy of the liver and occurs predominantly in individuals with underlying liver disease or cirrhosis [1]. HCC accounts for approximately 800,000 deaths annually, making it one of the most lethal cancers in adults [2,3]. Host genetics play an important role in predisposing individuals to the risk of fibrosis progression and HCC. In this regard, several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been reported to be associated with HCC development [4]. One SNP, rs17047200, is located in the Tolloid like 1 (TLL1) gene on chromosome 4 [5–7] and encodes for a metalloprotease.

Genome-wide association studies from Japan showed a strong association between the TLL1 variant and HCV patients who later developed HCC after antiviral treatment [5,6]. However, studies performed in European [7] and Egyptian populations [8] did not show any association between TLL1 polymorphisms and cirrhotic HCV patients who later developed HCC after viral treatment. In addition, a study from Japan showed advanced fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) associated with TLL1 genotype AT/TT compared to AA [9]. However, these results were not confirmed in a cohort of Caucasian patients with MASLD [10]. These studies suggest a differential association of TLL1 in HCC depending on the population.

To our knowledge, no studies have been performed to assess TLL1 polymorphisms and the risk of HCC in Latin Americans, a population with a high incidence of both MASLD and HCV-related HCC [11,12]. In this study, we evaluated the risk association of the TLL1 SNP in a well-defined Latin American cohort with HCC and compared it to a European cohort.

2Materials and Methods2.1Selection criteria for patient inclusionA cross-sectional study analysis was conducted using data from the ESCALON network [13,14], which is a European-Latin American network that evaluates clinical and genetic factors for discovering biomarkers in early diagnosis and treatment of hepatobiliary tumors (www.escalon.eu). HCC patients were diagnosed through radiological evidence in accordance with European and American [15,16]. Patients with sufficient information on liver disease etiology, tumor size, and fibrosis status were included. The exclusion of patients includes HCC recurrence, non-HCC liver metastases, mixed-type HCC, age < 18 years, and co-existing non-HCC malignancies.

2.2Patient cohortsThis cohort included patients from Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) and Europe (The Netherlands) since 2019. Medical records and confirmatory imaging, pathology, and laboratory tests were used to identify the etiology, tumor stage, and fibrosis stage. Details on etiology, tumor stage, and other information can be found in Table 1.

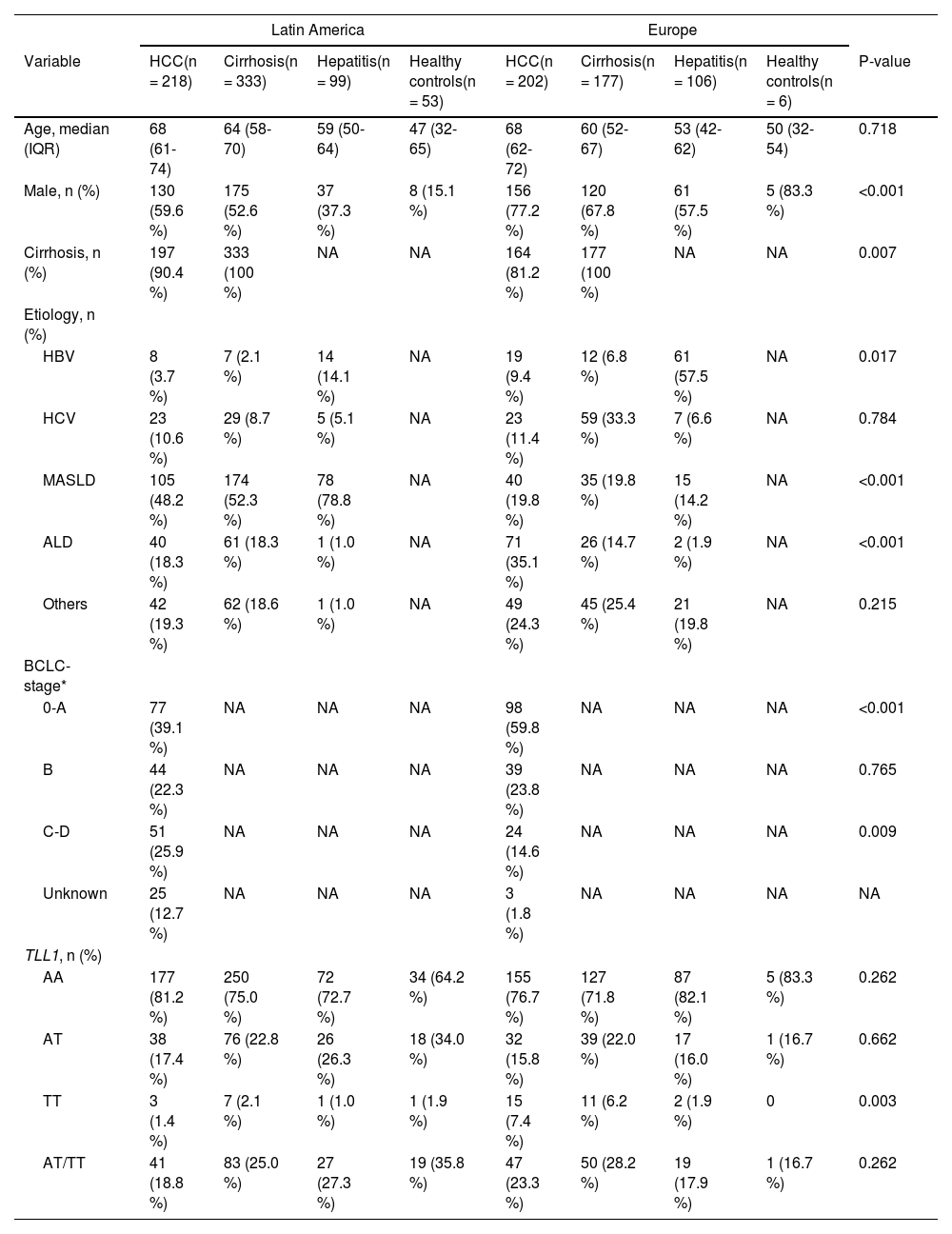

Patient's information of the Latin American and European cohort

ALD, alcoholic liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; TLL1, Tolloid like 1; P-value, the comparison of variables among HCC patients from Latin America and Europe; NA, not available; *, only cirrhotic HCC patients have BCLC stage.

Etiology assessment: Patients with HBV or HCV infection were diagnosed serologically. Patients with MASLD had either a diagnosis assigned by the managing hepatologists or evidence of hepatic steatosis by histopathology or ultrasound, without other liver damage triggers. Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) had persistent steatohepatitis following an estimated daily ethanol intake of more than 40 g/day for men and more than 30 g/day for women for over 10 years, in the absence of other liver diseases. Other etiologies included alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, acquired immune deficiencies, autoimmune liver disease, hemochromatosis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson's disease, a documented clinical history of immunomodulatory drugs, pathology-proven Metavir F2-F3 fibrosis without risk factors, and monogenic syndromes. Patients with HBV or HCV infection were assigned to the viral group, and patients with MASLD or ALD were assigned to the non-viral group.

Tumor stage and fibrosis evaluation: For patients with cirrhotic HCC, the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system was used [17]. The presence of severe fibrosis or cirrhosis was established by the managing hepatologists through pathology (Metavir ≥F3-F4) or liver transient elastography studies (> 12.0 kPa).

2.3Serum collectionSerum was collected prospectively starting from 2019 and onwards specifically for HCC biomarker discovery and validation studies. A data monitor regularly checks all data. The control group was required to have a minimum follow-up of 24 months after biomarker assessment to confirm the absence of HCC. Serum samples from patients diagnosed with HCC were collected at the time of diagnosis. DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood of 1194 patients from Argentina, Peru, Chile, Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and the Netherlands (as a European control cohort).

2.4TLL1 SNPWe analyzed the proportion of the rs17047200 variant located within the TLL1 gene for individuals with and without HCC within the Latin American and European populations. The TLL1 rs17047200 SNP was genotyped using TaqMan probe: TTTTGCCCACTTATGTCCATTTCAC [A/T] GTTCATTGACATCTATTTCTGAAGG (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 4351376). Genotyping was performed using StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher) and a Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems).

2.5StatisticsStatistical analyses were performed by SPSS 28.0.1.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as medians, and categorical variables as percentages. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to test continuous variables, and chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used to test dichotomous variables. Logistic regression was used to examine the association between HCC and the TLL1 variant. A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6Ethical statementsWritten informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the local and/or regional Ethics Committees of all centers.

3ResultsThe study included 1,194 individuals, including 420 HCC (86 % cirrhotic) and 774 controls (65.9 % cirrhotic). As presented in Table 1, the Latin American cohort consisted of 218 individuals with HCC (90.4 % cirrhotic), 333 with cirrhosis without HCC, 99 with chronic viral hepatitis, and 53 healthy controls. The European cohort consisted of 202 individuals with HCC (81.2 % cirrhotic), 177 with cirrhosis without HCC, 106 with chronic viral hepatitis, and 6 healthy controls. The median age of HCC individuals was 68 years (IQR: 61 to 74) among Latin Americans and 68 years (IQR: 62 to 72) among Europeans. 59 % and 77 % of Latin American and European with HCC were males, respectively. The most common cause of HCC in the Latin American cohort was MASLD (48 %), while in the European cohort it was ALD (35 %). Detailed characteristics of the study populations by HCC status with statistical analyses are summarized in Table 1.

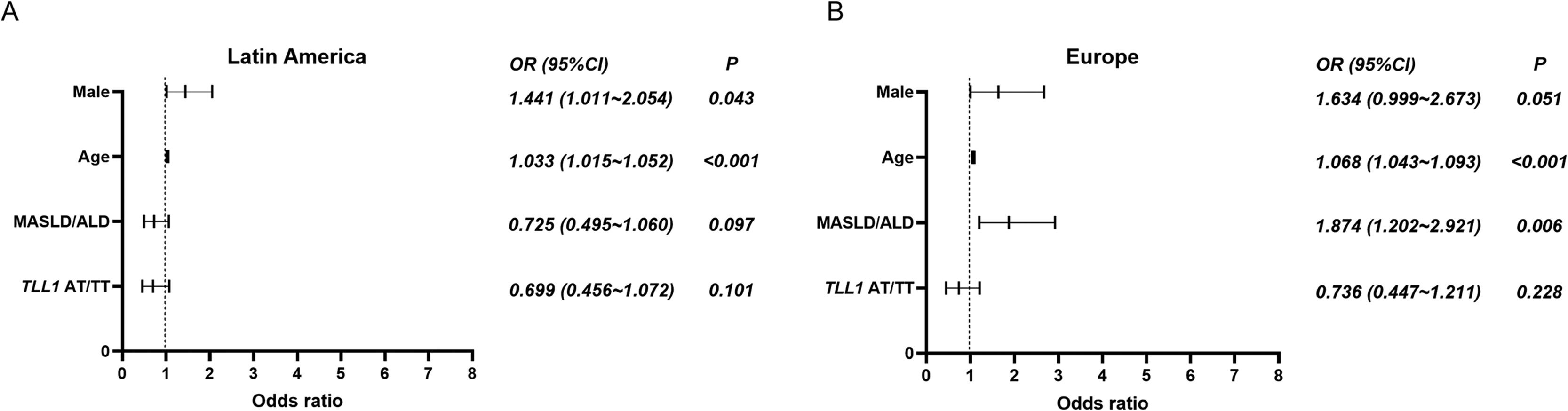

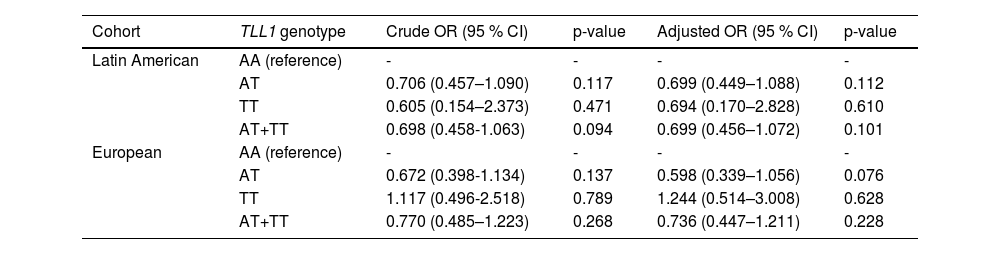

In the Latin American cohort, the proportion of the TLL1 pathogenic variant AT/TT among HCC patients was lower than among patients with cirrhosis (18.8 % versus 25.0 %), but no statistical difference was found (p = 0.093, Table 1). Similarly, European patients with HCC had a lower proportion of TLL1 AT/TT than those with cirrhosis without HCC (23.3 % versus 28.2 %, p = 0.268, Table 1). In addition, no significant differences were observed in the comparison of HCC patients from Latin America and Europe (18.8 % versus 23.3 %, p = 0.262). When adjusted for gender, age, and etiology (MASLD or ALD), TLL1 AT/TT was found not to be a risk factor for the development of HCC in Latin Americans when compared to patients with cirrhosis (OR: 0.699, 95 %CI 0.456-1.072, p = 0.101, Fig. 1, Table 2). A similar finding was observed when comparing HCC versus cirrhosis in the European cohort (OR: 0.736, 95 %CI 0.447-1.211, p = 0.228) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Next, we analyzed the association of TLL1 AT/TT in a Latin American cohort with self-reported Latin American ancestry (n = 185) and found that the SNP did not represent a risk factor for HCC (OR: 0.643, 95 %CI 0.285-1.451, p = 0.288; adjusted OR: 0.551, 95 %CI 0.224-1.353, p = 0.193) compared to cirrhosis.

Logistic regression analysis was performed on HCC patients and cirrhotic non-HCC patients from Latin America and Europe. (A) In Latin America, age and male are risk factors for HCC development. (B) In Europe, age and etiology (MASLD and ALD) are risk factors for HCC. TLL1 AT/TT is not a risk factor for HCC development in either population. References for TLL1 AT/TT, etiology (MASLD and ALD), and male are TLL1 genotype AA, other etiologies, and female, respectively. Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; TLL1, Tolloid like 1; OR, odds ratio.

TLL1 rs17047200 in the development of HCC compared to cirrhosis in Latin American and European cohort

Note: adjusted by age, gender, and etiology (MASLD/ALD). ALD, alcoholic liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; TLL1, Tolloid like 1.

The minor allele frequency (MAF) of TLL1 rs17047200 A>T in the public database (dbSNP, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/) was 11.3 % (sample size 610) and 13.1 % (sample size 16,444) for Latin Americans and Europeans, respectively. In our study cohort, the minor allele frequencies were similar for patients with HCC (Latin America 10.0 %, Europe 15.4 %) or cirrhosis (Latin America 13.5 %, Europe 17.2 %) compared to the dbSNP database.

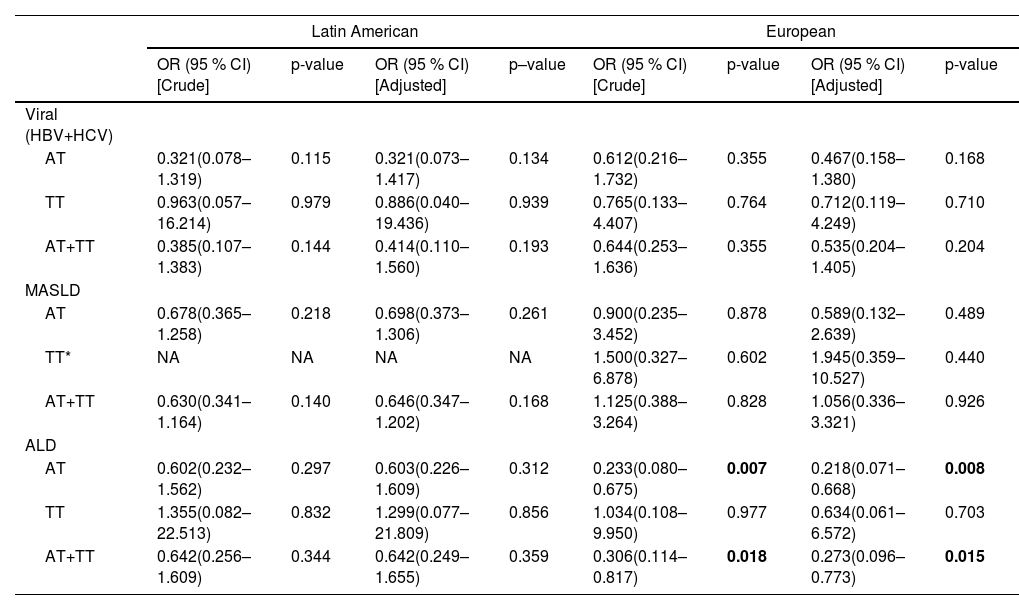

Next, we performed sub-group analysis on underlying liver disease (MASLD, ALD, viral hepatitis). We found that the TLL1 genotype AT/TT is not associated with viral- or MASLD-related HCC compared to cirrhosis in both the Latin American or the European cohort (p > 0.05) (Table 3). Interestingly, in the European cohort, patients with ALD-related HCC (13 out of 71) exhibited a lower frequency of TLL1 AT/TT genotypes (18.3 % versus 42.3 %, p = 0.015) than those with cirrhosis (11 out of 26, OR: 0.273, 95 %CI 0.096-0.773, p = 0.015, Table 3), which was predominantly due to a lower frequency of the AT genotype. In contrast to Europeans, no difference was found among Latin American ALD-related HCC patients (22.5 %, 9 out of 40) compared to cirrhosis (31.1 %, 19 out of 61, p = 0.342) as assessed by chi-square test.

TLL1 rs17047200 in the development of HCC compared to cirrhosis with respective etiology in Latin American and European cohort

Note: adjusted by gender and age. Reference allele of TLL1 is AA. *, In Latin American cohort, none of MASLD patients with HCC had TLL1 genotype TT. ALD, alcoholic liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; TLL1, Tolloid like 1.

Studies have reported that the TLL1 genotype AT/TT is associated with fibrosis stages in MASLD patients from Japan [9]. To examine this, we assessed the proportion of the TLL1 pathogenic variant (AT/TT) among MASLD individuals without cirrhosis (n = 78) and with cirrhosis (n = 174) in Latin Americans. No statistical difference was observed for the proportion of the TLL1 genotype AT/TT between MASLD-hepatitis (21.8 %, 17 out of 78) and MASLD-cirrhosis (24.7 %, 43 out of 174, p = 0.615), suggesting that in Latin America the TLL1 genotype AT/TT was not associated with fibrosis stages in MASLD patients (adjusted OR: 0.975, 95 %CI 0.496–1.918, p = 0.941).

4DiscussionThis is the first report on the association between the genetic variant TLL1 rs17047200 and HCC in a cohort of Latin American patients compared to Europeans. We found that a TLL1 polymorphism is not associated with HCC development in either population. Also, the TLL1 AT/TT genotype does not appear to be associated with MASLD- or viral-related HCC development as well as the fibrosis stages of MASLD. Although two studies from Japan found an association between TLL1 rs17047200 and HCC development after eradication of HCV infection [5,6], two longitudinal studies from Europe [7] and Egypt [8] suggested that the TLL1 variant is not a predictive biomarker for HCV patients who later developed HCC after antiviral treatment. In our cohorts, we were unable to analyze this due to a limited group size of HCV-infected patients. Also, different from the longitudinal Japanese studies, we conducted a cross-sectional study since we collected serum from HCC patients at the first time of diagnosis. It should be noted that cirrhotic controls were followed for a minimum of 24 months. However, in the analysis of HCC linked to the viral infection group we did not observe an association, that may relate to different population characteristics. Ethnic background may be important, but no difference was found in the Latin American cohort when we divided patients according to self-reported ancestry. Our study did not count with enough individuals of reported Asian ancestry to perform a sub-group analysis in this group. It should be noted that self-reported ethnicity is not as accurate as patient's genetic information. Although one Japanese study found that the combination of PNPLA3 and TLL1 polymorphisms can predict the advanced fibrosis stage in MASLD patients [9], no association between the TLL1 genotype itself and fibrosis stages of MASLD patients was observed in our Latin American cohort. In contrast, in the European cohort, ALD-related HCC patients had a lower frequency of TLL1 AT/TT genotype than cirrhosis patients, which was not observed for the Latin American cohort.

5ConclusionsFor the first time, this study revealed a negative association between TLL1 rs17047200 and the occurrence of HCC in patients from Latin America. Our study highlights the importance of addressing specific ethnic cohorts and etiology when assessing the genetic risk of HCC. A larger study confirming these findings and integrating specific ethnic and etiology backgrounds within groups is warranted.

FundingThis study was supported by the European-Latin American ESCALON consortium, funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program, project number 825510, sponsored by the Foundation for Liver and Gastrointestinal Research (SLO), China Scholarship Council for funding PhD fellowship to S.F. (no. 202108500043), and NIH-R21TW012390-01A1. M.A. acknowledges partial support from Chilean government through the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT grant 1191145).

S.F. was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis and writing. A.B. and J.D. were involved in conceptualization, supervision, writing and funding acquisition. D.K., J.P., D.B., J.F., A.M., M.A., E.C, J.O. were involved in data curation, methodology and reviewing and editing the manuscript.