With the aim of making informed decisions on resource allocation, there is a critical need for studies that provide accurate information on hospital costs for treating pediatric asthma exacerbations, mainly in middle-income countries (MICs). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the direct medical costs associated with pediatric asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance in Bogota, Colombia.

Patients and methodsWe reviewed the available electronic medical records (EMRs) for all pediatric patients who were admitted to the Fundacion Hospital de La Misericordia with a discharge principal diagnosis pediatric asthma exacerbation over a 24-month period from January 2016 to December 2017. Direct medical costs of pediatric asthma exacerbations were retrospectively collected by dividing the patients into four groups: those admitted to the emergency department (ED) only; those admitted to the pediatric ward (PW); those admitted to the pediatric intermediate care unit (PIMC); and those admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

ResultsA total of 252 patients with a median (IQR) age of 5.0 (3.0–7.0) years were analyzed, of whom 142 (56.3%) were males. Overall, the median (IQR) cost of patients treated in the ED, PW, PIMC, and PICU was US$38.8 (21.1–64.1) vs. US$260.5 (113.7–567.4) vs. 1212.4 (717.6–1609.6) vs. 2501.8 (1771.6–3405.0), respectively: this difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe present study helps to further our understanding of the economic burden of pediatric asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance among pediatric patients in a MIC.

Childhood asthma is the most common chronic disease among children and a major public health problem in the USA as well as in many other countries, such as Colombia.1,2 The disease has been associated with a significant clinical and economic burden, not only for healthcare systems but also for patients, their families, and society as a whole,3 mainly in middle-income countries (MICs).4

Despite significant advances in the treatment of asthma, particularly over the past 20 years, many patients continue to suffer sub-optimal control of symptoms, resulting in the disease being a leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions among children in various parts of the world.5 Among the total costs of the disease, ED visits and hospital admissions for asthma exacerbations account for almost three quarters of the direct cost of the disease.6 The substantial clinical and economic burden of pediatric asthma exacerbations justifies the continuing efforts that have been made to reduce this burden through prevention and treatment measures such as successful educational interventions and effective pharmacological therapies.7

Understanding the costs associated with the management of pediatric asthma exacerbations is essential in terms of public policy considerations for making informed decisions on resource allocation and setting priorities for child health, thereby helping to ensure the most efficient use of health resources, especially in MICs, where these resources are always scarce. This is because, among other reasons, although pharmacological therapies have the potential to decrease the burden and costs of asthma, in recent years more expensive medications for the treatment of asthma have become available, such as combination inhalers and biological treatments.8

However, despite their importance, a review of the literature reveals a scarcity of published data regarding pediatric asthma exacerbations in MICs. Although we acknowledge the publication of previous cost-of-illness studies on pediatric asthma in high-income countries,9–12 and these studies have provided valuable information regarding the economic burden of the disease, little knowledge of treatment costs in MICs exists. Due to the well-known variation in healthcare costs between countries with various types of health care systems, mainly due to differences in the prices of labor and goods, including pharmaceuticals, as well as administrative costs,13,14 it is inappropriate to extrapolate costs of pediatric asthma exacerbations from high-income countries to MICs.

Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the direct medical costs associated with asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance among pediatric patients resident in Bogota, Colombia, an MIC located in South America.

Material and methodsStudy siteBogota, the capital city of Colombia, a tropical MIC located in South America, contains one fifth of Colombia’s population and is located at an elevation of about 2650m (8660ft) above sea level. In Colombia, a recent population-based study reported an increase in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms compared to previous reports, with a current prevalence of asthma symptoms of 18.9% (95% CI, 15.2–22.8) in children aged between 1 and 4 years and 16.8% (95% CI, 11.3–22.3) in children aged between 5 and 17 years, with 43% (95% CI, 36.3–49.2) reporting having required an ED or hospitalization in the past 12 months.2 The Fundación Hospital La Misericordia is a tertiary care university-based children’s hospital located in the metropolitan area of Bogota that receives patients from the majority of, and the most representative, public and private medical insurance companies in the city and the country.

Study designWe reviewed the available electronic medical records (EMRs) for all pediatric patients who were admitted to the Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia with a principal discharge diagnosis of asthma exacerbation over a 24-month period from January 2016 to December 2017. After reviewing the EMRs, we collected the following demographic and clinical data: age, gender, month of hospitalization, and the hospital service to which the patients were admitted: patients requiring emergency department (ED) consultation only; those requiring admission to the pediatric ward (PW); those requiring admission to the pediatric intermediate care unit (PIMC); and those requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

In our institution, the admission criteria to the PIMC for asthma exacerbations include one or more of the following criteria: worsening hypoxemia or hypercapnia, worsening respiratory distress, continuing requirement for more than 50% oxygen, requirement for intense or continuous nebulization therapy, hemodynamic instability, altered mental state, or air leak syndrome. Additionally, patients with respiratory failure and need of invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation are transferred to the PICU.

We excluded all patients with a primary diagnosis of asthma exacerbation treated on an outpatient basis and not requiring ED treatment. Likewise, we excluded patients whose asthma exacerbation was judged to not be the primary cause of the patient’s hospital attendance. Eligible patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of asthma exacerbation were identified by means of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code J45.

Cost analysisDirect medical and non-medical cost data were collected from the healthcare provider’s perspective. The following clinical and resource utilization data, which in turn were grouped into four categories, were extracted from EMRs of included patients: medical and therapy services (including respiratory therapy), diagnostics tests and procedures (hemogram, C-reactive protein, and imagenologic studies), consumables (medications, fluids, supplies, nebulization, and oxygen treatment), and hotel services (hospital stay). Data on resource use at an individual patient level, including length of stay (LOS), the quantity of medications and supplies utilized, and the number of diagnostic tests and procedures were collected.

The unit costs of each of the components of the four above-mentioned categories, including the bed-cost per day, were primarily obtained from hospital accounting reports.

Thereafter, we calculated the cost per asthma episode exacerbation based on the unit cost of each component multiplied by the resource quantities utilized by each patient.

Costs were calculated and presented separately in four groups based on the hospital service to which the patient was admitted: 1) patients admitted to the ED only (ED group), 2) patients admitted to the PW only (PW group), 3) patients admitted to the PIMC, with or without admission to the PW, but without admission to the PICU (PIMC group), and 4) patients admitted to the PICU, with or without admission to the PIMC or to the PW (PICU group).

Costs were calculated in Colombian pesos (COPs) and converted to dollars (US$s)=based on the average exchange rate for 2018 (1US$ 2956.55 COP).15 All the costs were converted and adjusted to 2018 US dollars.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics board.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation (SD) or median interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality of the data distribution. Normality of the continuous variable distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentage). As was mentioned above, the results were calculated and presented separately for the following four groups: ED, PW, PIMC, and PICU.

Differences in direct costs between patients assigned to each one of the four groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance ANOVA (with the post-hoc Tukey test) or the non-parametric ANOVA Kruskall-Wallis test (with the post-hoc Dunn test), depending on the normality of the data distribution.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the significance level used was 0.05. The data were analyzed with the statistical package Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

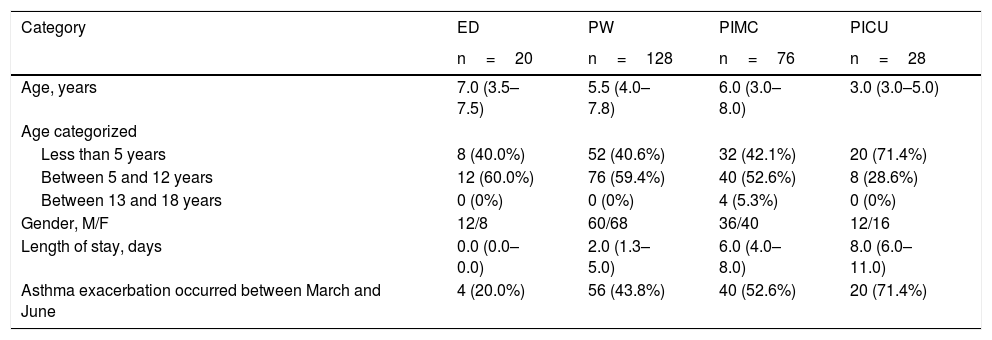

ResultsStudy populationDuring the study period, there were 252 patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of asthma exacerbations. Of the 252 patients included, 20 (7.9%) were admitted to the ED, 128 (50.8%) to the PW, 76 (30.2%) to the PIMC, and the remaining 28 (11.1%) to the PICU. Of the 252 patients included, 142 (56.3%) were males, and the median (IQR) age was 5.0 (3.0–7.0) years, with patients requiring admission to the PICU being younger when compared with the other three groups, although this difference was not statistically significant (7.0 (3.5–7.5) vs. 5.5 (4.0–7.8) vs. 6.0 (3.0–8.0) vs. 3.0 (3.0–5.0)) years, for ED, PW, PIMC, and PICU groups, respectively, p=0.30). The age group distribution was 112 (44.4%) less than five years, 136 (54.0%) between five and 12 years, and the remaining four (1.6%) between 13 and 18 years. Out of the total of 252 hospital events analyzed, 120 (47.6%) occurred between the months of March and June, the period of time that roughly coincides with the first rainy season in the city.16 Regarding LOS, the median (IQR) was 4.0 (2.0–7.0) days overall, this value being significantly different between patients admitted to PW, PIMC, and PICU (2.0 (1.3–5.0) vs. 6.0 (4.0–8.0) vs. 8.0 (6.0–11.0), respectively, p<0.001). The study population characteristics categorized by the hospital service to which the patient was admitted are presented in Table 1.

Study population characteristics categorized by the hospital service to which the patient was admitteda.

| Category | ED | PW | PIMC | PICU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=20 | n=128 | n=76 | n=28 | |

| Age, years | 7.0 (3.5–7.5) | 5.5 (4.0–7.8) | 6.0 (3.0–8.0) | 3.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Age categorized | ||||

| Less than 5 years | 8 (40.0%) | 52 (40.6%) | 32 (42.1%) | 20 (71.4%) |

| Between 5 and 12 years | 12 (60.0%) | 76 (59.4%) | 40 (52.6%) | 8 (28.6%) |

| Between 13 and 18 years | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gender, M/F | 12/8 | 60/68 | 36/40 | 12/16 |

| Length of stay, days | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.0 (1.3–5.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 8.0 (6.0–11.0) |

| Asthma exacerbation occurred between March and June | 4 (20.0%) | 56 (43.8%) | 40 (52.6%) | 20 (71.4%) |

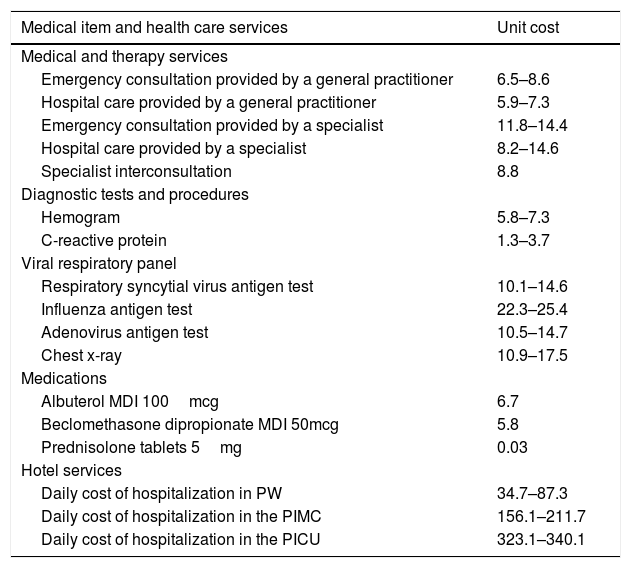

Unit costs of direct medical items and health care services are presented in Table 2.

Unit costs of direct medical items and health care servicesa.

| Medical item and health care services | Unit cost |

|---|---|

| Medical and therapy services | |

| Emergency consultation provided by a general practitioner | 6.5–8.6 |

| Hospital care provided by a general practitioner | 5.9–7.3 |

| Emergency consultation provided by a specialist | 11.8–14.4 |

| Hospital care provided by a specialist | 8.2–14.6 |

| Specialist interconsultation | 8.8 |

| Diagnostic tests and procedures | |

| Hemogram | 5.8–7.3 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.3–3.7 |

| Viral respiratory panel | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus antigen test | 10.1–14.6 |

| Influenza antigen test | 22.3–25.4 |

| Adenovirus antigen test | 10.5–14.7 |

| Chest x-ray | 10.9–17.5 |

| Medications | |

| Albuterol MDI 100mcg | 6.7 |

| Beclomethasone dipropionate MDI 50mcg | 5.8 |

| Prednisolone tablets 5mg | 0.03 |

| Hotel services | |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in PW | 34.7–87.3 |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in the PIMC | 156.1–211.7 |

| Daily cost of hospitalization in the PICU | 323.1–340.1 |

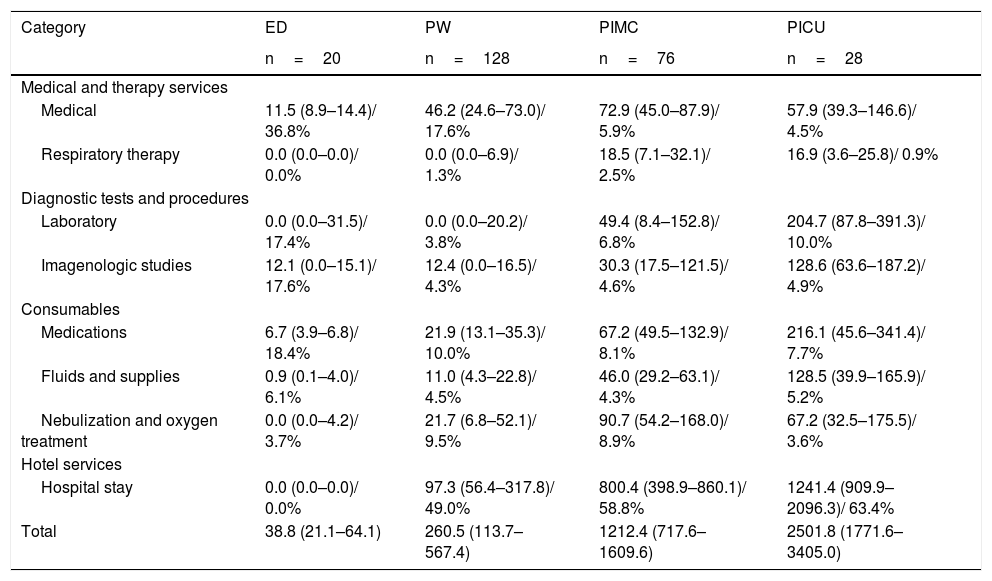

With respect to the hospital service to which the patient was admitted, overall, the median (IQR) cost of patients treated in the ED, PW, PIMC, and PICU was US$38.8 (21.1–64.1) vs. US$260.5 (113.7–567.4) vs. 1212.4 (717.6–1609.6) vs. 2501.8 (1771.6–3405.0), respectively, this difference being statistically significant (p<0.001). The in-patient care costs of patients treated in the PIMC or PICU were approximately 4.5–9.5 times greater than those for patients treated in the PW.

With regard to the proportion of resources and services billed according to the hospital setting to which the patients were admitted, in general, the more severely ill the patient was (patients requiring PIMC or PICU admission), the greater the percentage of the bill attributable to hotel services (hospital stay) was and the lower the percentage of the bill attributable to medical services and medications was (Table 3).

Total median costs associated with asthma exacerbations categorized by the hospital service to which the patient was admitteda.

| Category | ED | PW | PIMC | PICU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=20 | n=128 | n=76 | n=28 | |

| Medical and therapy services | ||||

| Medical | 11.5 (8.9–14.4)/ 36.8% | 46.2 (24.6–73.0)/ 17.6% | 72.9 (45.0–87.9)/ 5.9% | 57.9 (39.3–146.6)/ 4.5% |

| Respiratory therapy | 0.0 (0.0–0.0)/ 0.0% | 0.0 (0.0–6.9)/ 1.3% | 18.5 (7.1–32.1)/ 2.5% | 16.9 (3.6–25.8)/ 0.9% |

| Diagnostic tests and procedures | ||||

| Laboratory | 0.0 (0.0–31.5)/ 17.4% | 0.0 (0.0–20.2)/ 3.8% | 49.4 (8.4–152.8)/ 6.8% | 204.7 (87.8–391.3)/ 10.0% |

| Imagenologic studies | 12.1 (0.0–15.1)/ 17.6% | 12.4 (0.0–16.5)/ 4.3% | 30.3 (17.5–121.5)/ 4.6% | 128.6 (63.6–187.2)/ 4.9% |

| Consumables | ||||

| Medications | 6.7 (3.9–6.8)/ 18.4% | 21.9 (13.1–35.3)/ 10.0% | 67.2 (49.5–132.9)/ 8.1% | 216.1 (45.6–341.4)/ 7.7% |

| Fluids and supplies | 0.9 (0.1–4.0)/ 6.1% | 11.0 (4.3–22.8)/ 4.5% | 46.0 (29.2–63.1)/ 4.3% | 128.5 (39.9–165.9)/ 5.2% |

| Nebulization and oxygen treatment | 0.0 (0.0–4.2)/ 3.7% | 21.7 (6.8–52.1)/ 9.5% | 90.7 (54.2–168.0)/ 8.9% | 67.2 (32.5–175.5)/ 3.6% |

| Hotel services | ||||

| Hospital stay | 0.0 (0.0–0.0)/ 0.0% | 97.3 (56.4–317.8)/ 49.0% | 800.4 (398.9–860.1)/ 58.8% | 1241.4 (909.9–2096.3)/ 63.4% |

| Total | 38.8 (21.1–64.1) | 260.5 (113.7–567.4) | 1212.4 (717.6–1609.6) | 2501.8 (1771.6–3405.0) |

The present study shows that pediatric asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance among pediatric patients place a significant economic burden on the Colombian healthcare system, the burden being greater as the severity of the exacerbations increase. In this regard, although approximately only 10% of asthma exacerbations were severe enough to require PICU admission in our population, they consumed about 60% of the resources allocated to the disease, with approximately a 9.5-fold higher direct asthma-related cost than for children requiring only PW admission. Resource use and cost data were collected separately for four hospital services to which the patients were admitted, and in turn were grouped into four categories (medical, nursing and therapy services; diagnostics tests and procedures; consumables; and hotel services). The latter allowed establishing the proportion of resources and services billed according to the hospital setting to which the patients were admitted, showing that in general the more severely ill the patient, the greater the percentage of the bill attributable to hotel services (hospital stay) and the lower the percentage of the bill attributable to medical services and medications.

The most remarkable result to emerge from the data is that it further enhances understanding of the impact of pediatric asthma by estimating the economic burden of pediatric asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance in an MIC. This is essential in terms of public policy considerations for assisting with decisions on priorities and budgets for healthcare. Likewise, this is important for an accurate assessment of cost-effectiveness of public health policies targeting the achievement of better asthma control and for estimating the cost-effectiveness of costly pharmacological asthma therapies. Specifically, although not exclusively, our results could serve as an input for models for assessing the cost-effectiveness of both current and future combination inhalers and biological agents in severe asthma. Additionally, due to the fact that hospital LOS is one of the main drivers of costs, it is conceivable that interventions that have been demonstrated to be successful in lowering the pediatric asthma hospital LOS, such as standardized evidence-based clinical care pathways17–19 and checklists to expedite discharge,19 could be useful in lowering the costs to pediatric patients treated for asthma exacerbations.

Although data on asthma costs from different countries are not easily comparable, our results are in good agreement with those obtained in a recent study performed in Turkey, a country with an upper-middle-income economy in which the treatment cost was the predominant direct cost item, followed by healthcare resource utilization, diagnostic tests, and consultation costs.9 Likewise, the total direct cost per attack was significantly higher in patients with severe asthma attacks when compared to moderate and mild attacks.9 Our data concerning the proportion of resources and services billed are also in line with those reported in another Turkish study in which hospitalization was documented to be one of the main items responsible for the burden of asthma on health economics.20 There are also reports indicating that patients hospitalized for exacerbations contribute significantly to the total asthma-related healthcare costs, determining that exacerbations that were associated with a hospitalization accounted for 90% of the total costs of exacerbations.21 Furthermore, also supporting our findings, a systematic review of the economic burden of asthma that included sixty-eight studies concluded that hospitalization was one of the most important cost drivers of direct costs.3 In this systematic review, the largest amount of direct costs found was that allocated to in-patient hospitalization, accounting for 47 to 86% of the overall asthma-related costs.3 However, in contrast to our findings, many reports have established that medications are one of the key cost drivers among the direct asthma-related healthcare costs.3,22–25 In our study, medications represented only a minor proportion of the total asthma-related healthcare costs among the different severity grades of asthma exacerbations. Although the reasons for this discrepancy are not clearly understood, it is possible that the implementation of generic drug policies by the World Health Organization (WHO) to improve the availability of affordable and effective medicines in Latin America,26 pharmaceutical purchasing policies, drug pricing regulation policies, price negotiations, reference pricing, index pricing, and pricing policies based on volume are implicated.27,28

With regard to the reported direct cost of managing pediatric asthma exacerbations, our findings are in good agreement with previous institutional studies performed in other countries, showing that the direct mean costs of asthma exacerbations range between US$295.5 and US$2493.3 after conversion and adjusting into 2018 US dollars.3 However, we found much lower costs for asthma exacerbations with respect to those reported in countries with high-income economies, such as the United States, with direct mean costs of asthma exacerbations ranging between US$4449.6 and US$6540.6.29 The observed differences in costs of asthma exacerbations between countries likely result from many factors. It has been well described in the literature that variation in healthcare costs between countries with various types of health care systems may be due to several causes such as prices of labor, services and goods, including pharmaceuticals, volume of resources, administrative costs, use of high-tech interventions, access to and provision of specialized care instead of primary care, and payment schemes.14,30 Of these, prices of labor and goods, including pharmaceuticals and administrative costs, appeared to be the major drivers of the variation in costs between countries, especially between the United States and other countries.13,14 Our results corroborate the expected international cost differences in hospitalization costs from pediatric asthma exacerbations, and highlight the importance of their accurate estimation in different countries in order to be of help in allowing fair allocation of resources within the health care system of each of these countries.

We are aware that our research may have at least three limitations. The first is that the study focused only on the costs associated with asthma exacerbations and did not include other costs such as indirect and intangible costs. Although inpatient care accounts for a high proportion of the total costs of asthma exacerbations, the exclusion of indirect and intangible costs could have underestimated the actual costs associated with pediatric asthma exacerbations. The second is that our study was limited to patients hospitalized at a single tertiary-care pediatric hospital, and it is possible that our findings would not be generalizable to all asthmatic patients. However, the Fundación Hospital La Misericordia receives patients from the majority of and the most representative public and private medical insurance companies in the city and the country and therefore could be considered to be representative of the asthma costs of the entire country. The third is our inability to calculate marginal increased costs resulting from patients moving through hospital services of increasing complexity. These limitations warrant further research in other hospitals and other settings that also take into consideration indirect and intangible costs.

In conclusion, the present study helps to further our understanding of the economic burden of asthma exacerbations requiring hospital attendance among pediatric patients in a tropical MIC. This is essential for assessment of the cost-effectiveness of interventions in order to help ensure the most efficient use of health resources within the Colombian healthcare system and probably other similar MICs. Future studies should consider not only the direct medical costs associated with pediatric asthma exacerbations but also indirect and intangible costs.

Declarations of interestNone.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors thank Mr. Charlie Barret for his editorial assistance.