The study aimed to analyze the role of depression and impulsivity in the psychopathology of bulimia nervosa (BN).

Materials and methodsSeventy female patients with DSM-IV BN, purging subtype, were assessed for eating-related symptoms, body dissatisfaction, affective symptoms, impulsivity, and personality traits. Factor analysis and structural equation modeling methods were used for statistical analysis.

ResultsBN appeared as a condition which incorporated 5 general dimensions: (a) binge eating and compensatory behaviors; (b) restrictive eating; (c) body dissatisfaction; (d) dissocial personality traits; and (e) a cluster of features which was called “emotional instability”. The 5 obtained dimensions can be grouped into 2 basic factors: body dissatisfaction/eating behavior and personality traits/psychopathology. The first one contains the clinical items used for the definition of BN as a clinical condition in the DSM-V and the International Classification of Diseases 10, and reflects the morphology and the severity of the eating-related symptoms. The second dimension includes a cluster of symptoms (depressive symptoms, impulsivity, and borderline, self-defeating and dissocial personality traits) which could be regarded as the “psychopathological core” of BN and may be able to condition the course and the prognosis of BN.

El presente estudio trató de analizar el papel de la depresión y la impulsividad en la psicopatología de la bulimia nerviosa (BN).

Materiales y métodosSe examinó a 70 mujeres con un diagnóstico de bulimia nerviosa basado en la cuarta revisión del Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-IV), subtipo purgativo, para los síntomas relacionados con el trastorno de la conducta alimentaria, insatisfacción corporal, síntomas afectivos, impulsividad y rasgos de personalidad. Para el análisis estadístico se utilizaron métodos de análisis factorial y de modelos de ecuaciones estructurales.

ResultadosLa BN se presentó como un proceso que incorporaba 5 dimensiones generales: a) episodios recurrentes de gran voracidad o «atracones» y conductas compensadoras; b) conducta alimentaria restrictiva; c) insatisfacción corporal; d) rasgos de personalidad disocial; y e) una agrupación (cluster) de características que se denominó «inestabilidad emocional». Las 5 dimensiones obtenidas pueden agruparse en 2 factores básicos: insatisfacción corporal/conducta alimentaria y rasgos de personalidad/psicopatología. El primero contiene los ítems clínicos utilizados para la definición de la BN como proceso clínico en el DSM-V y la Clasificación Internacional de las Enfermedades, y refleja la morfología y la gravedad de los síntomas relacionados con la conducta alimentaria. La segunda dimensión incluye una agrupación de síntomas (síntomas depresivos, impulsividad y rasgos límite de personalidad [borderline]), conducta autodestructiva y disocial) que podrían considerarse como la «base psicopatológica de la bulimia nerviosa» y pueden condicionar su curso y su pronóstico.

It has been proposed that impulsivity is a core feature in bulimia nervosa (BN), as well as a clinical dimension strongly associated to depression. Several studies have aimed to analyze this association in BN patients, but the results are inconclusive, since some of the studies support the association between impulsivity and depression,1–4 but others defend its independence from mood disorders.5–7

Several models of BN have been proposed in recent years. They suggest that BN should be conceived as a complex condition which integrates eating dysfunction, psychopathological symptoms, personality traits and other clinical features, usually from a multidimensional perspective. This conception of BN goes beyond the definitions proposed by the DSM-5 and the ICD-10, which are focused on body dissatisfaction and eating disturbances.

Based on the premise that subjects with restrained eating and patients with BN represented the edges of a continuum, Laessle and associates8 proposed a model of BN with two dimensions: dietary and weight concerns (with continuity between normal eaters and patients with BN) and general psychopathology (with a clear discontinuity between normal eaters and patients). A few years later, Tobin and associates9 defended the identity of BN as a specific condition with three core dimensions: (a) restrictive eating behaviors; (b) bulimic behaviors; and (c) mood and personality disorders. In 1993, Gleaves and associates proposed a four-dimensional model, adding a new factor: body dissatisfaction.10 They subsequently validated their results and proposed a final model based on five dimensions: (a) restricting behaviors; (b) bulimic behaviors; (c) body dissatisfaction; (d) mood and personality disorder; and (e) self-injurious behaviours.11 Using the reported studies as a starting point, our group proposed a five-dimensional model of BN which included borderline personality traits.12 The dimensions incorporated into our model were: (a) restricting behaviors; (b) bulimic behaviors; (c) body dissatisfaction; (d) dissocial personality traits; and (e) a cluster of clinical items we called psychological instability, which included depressive symptoms, self-defeating personality traits and borderline personality traits.

In this context, the present study aimed to analyze the relationship between impulsivity and depression in the psychopathology of BN, as well as their potential association with personality traits and personality disorders. To perform this analysis, we turned back to our model of BN, incorporating impulsivity to the variables. We used a new larger clinical sample, more specific assessment tools and more complex statistical procedures. Our hypothesis was that impulsivity would appear associated with depressive symptoms and dysfunctional personality traits in the resulting model.

Materials and methodsThe research was designed as a cross-sectional study on patients with normal weight fulfilling DSM-IV-TR criteria for BN, purging subtype. Seventy female outpatients seeking treatment for BN at a university Eating Disorder Unit (University Hospital Network of Badajoz, Spain) were recruited for the study. All patients were Caucasian. Selection criteria for patients were: (1) that they met at the time of assessment the diagnostic criteria for BN, purging subtype, according to the DSM-IV-TR; (2) that they had a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 18.5kg/m2 and below 35.0kg/m2; and (3) that they consented to enter the study. The study was approved by the University of Extremadura Institutional Review Board and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. After receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures, all participants signed written informed consent.

The mean age of the selected patients was 21.5 (SD 1.8; range 19–24). The mean BMI was 22.9kg/m2 (SD 3.4; range 19.0–34.0). The mean of binging at the time of the assessment was 1 per day (ranging from 2 to 35 per week), and the mean of vomiting was 1 per day (ranging from 2 to 21 per week).

For the assessment of the psychopathological variables, the following specific tools were used. Severity of the bulimic behaviors was assessed using the Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh (BITE), as well as the Bulimia subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2). Severity of the restrictive eating behaviors was assessed using the 40 items version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40), and the Drive for Thinness subscale of the EDI-2. We used the Body Image Assessment (BIA) and the Body Dissatisfaction subscale of the EDI-2 to assess body dissatisfaction. The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). For the assessment of impulsivity, the Impulsive Behaviour Scale-Revised (IBS-R) was used. Self-defeating personality traits were investigated using the Self-defeating personality subscale of the Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory (MCMI-2). Finally, borderline personality traits were assessed using a semi-structured interview, the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients-Revised (DIB-R). All scales had validated Spanish versions.

Factor analysis techniques were used to confirm the reciprocal relationship of the isolated clinical variables. As the initial model had five factors, we adjusted the number of factors to this value. We applied the principal components method and normalization with Varimax rotation with Kaiser. At a later moment, the influence of the dimension we called emotional instability on bulimic symptoms was tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) methods.

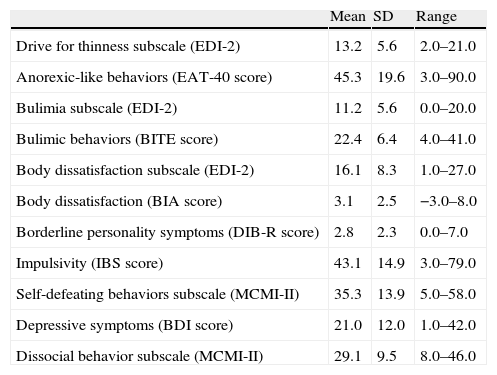

ResultsTable 1 shows the mean values and the standard deviation for each of the isolated items, as well as the range for each item.

Mean values, standard deviation, and range for each of the isolated items.

| Mean | SD | Range | |

| Drive for thinness subscale (EDI-2) | 13.2 | 5.6 | 2.0–21.0 |

| Anorexic-like behaviors (EAT-40 score) | 45.3 | 19.6 | 3.0–90.0 |

| Bulimia subscale (EDI-2) | 11.2 | 5.6 | 0.0–20.0 |

| Bulimic behaviors (BITE score) | 22.4 | 6.4 | 4.0–41.0 |

| Body dissatisfaction subscale (EDI-2) | 16.1 | 8.3 | 1.0–27.0 |

| Body dissatisfaction (BIA score) | 3.1 | 2.5 | −3.0–8.0 |

| Borderline personality symptoms (DIB-R score) | 2.8 | 2.3 | 0.0–7.0 |

| Impulsivity (IBS score) | 43.1 | 14.9 | 3.0–79.0 |

| Self-defeating behaviors subscale (MCMI-II) | 35.3 | 13.9 | 5.0–58.0 |

| Depressive symptoms (BDI score) | 21.0 | 12.0 | 1.0–42.0 |

| Dissocial behavior subscale (MCMI-II) | 29.1 | 9.5 | 8.0–46.0 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BIA: Body Image Assessment; BITE: Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh; SD: standard deviation; DIB-R: Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients-Revised; EAT-40: Eating Attitudes Test; EDI-2: Eating Disorder Inventory-2; IBS: Impulsive Behaviour Scale; MCMI-II: Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory.

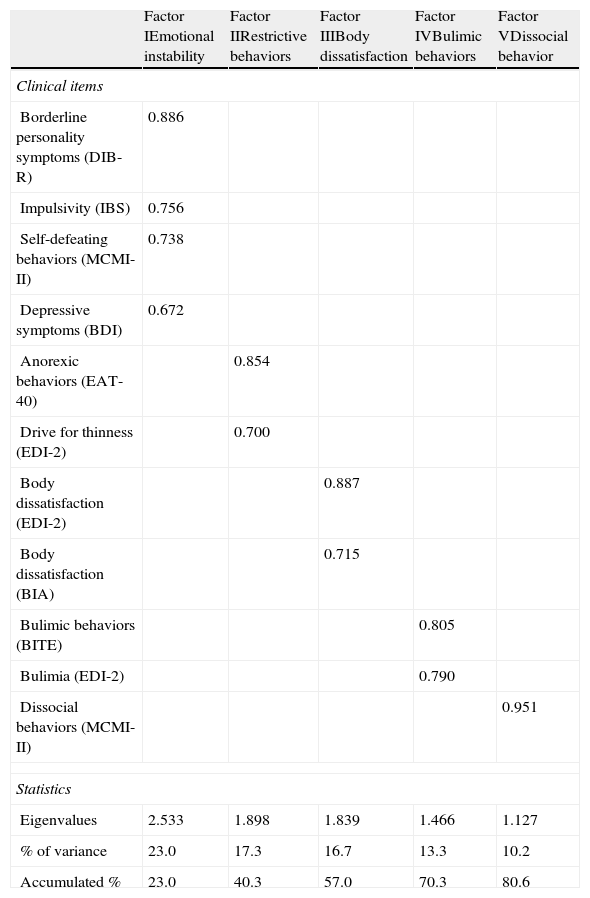

Table 2 shows the results from the factor analysis. As can be seen, the obtained model explained 80.6% of the variance, with five factors which explained 10.2–23.0% of the variance. To simplify the interpretation of the data, only the scores over 0.5 were considered in order to define the model, as reported in the table. As hypothesized, impulsivity was associated with depressive symptoms, appearing both items included in a group of symptoms that we decided to call emotional instability.

Results from the factor analysis.

| Factor IEmotional instability | Factor IIRestrictive behaviors | Factor IIIBody dissatisfaction | Factor IVBulimic behaviors | Factor VDissocial behavior | |

| Clinical items | |||||

| Borderline personality symptoms (DIB-R) | 0.886 | ||||

| Impulsivity (IBS) | 0.756 | ||||

| Self-defeating behaviors (MCMI-II) | 0.738 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms (BDI) | 0.672 | ||||

| Anorexic behaviors (EAT-40) | 0.854 | ||||

| Drive for thinness (EDI-2) | 0.700 | ||||

| Body dissatisfaction (EDI-2) | 0.887 | ||||

| Body dissatisfaction (BIA) | 0.715 | ||||

| Bulimic behaviors (BITE) | 0.805 | ||||

| Bulimia (EDI-2) | 0.790 | ||||

| Dissocial behaviors (MCMI-II) | 0.951 | ||||

| Statistics | |||||

| Eigenvalues | 2.533 | 1.898 | 1.839 | 1.466 | 1.127 |

| % of variance | 23.0 | 17.3 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 10.2 |

| Accumulated % | 23.0 | 40.3 | 57.0 | 70.3 | 80.6 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BIA: Body Image Assessment; BITE: Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh; DIB-R: Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients-Revised; EAT-40: Eating Attitudes Test; EDI-2: Eating Disorder Inventory-2; IBS: Impulsive Behaviour Scale; MCMI-II: Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory.

Fig. 1 aims to represent graphically the results, showing the five dimensions of the new model: (a) restrictive eating; (b) compulsive eating; (c) body dissatisfaction; (d) dissocial behaviors; and (e) the cluster of symptoms that we called emotional instability (depressive symptoms, self-defeating personality traits and borderline personality traits).

Fig. 2 shows the results from the SEM study applied to this last dimension. As can be observed, when the influence of emotional instability (unobserved variable) on bulimic symptoms (observed variable represented by the BITE total score) was analyzed, an appropriate goodness-to-fit was obtained [Chi-square=4.418; DF=5; p=0.491; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI)=1.010; and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)<0.001; CI for RMSEA=0.000–0.157], confirming the suitability of the model.

DiscussionOur study aimed to analyze the association of impulsivity and depression in the psychopathology of BN. We used the variables from a previous complex model of BN which included restricting behaviors (fasting and exercise), purging behaviors (vomiting and laxatives), body dissatisfaction (negative self-evaluation based on physical aspect), dissocial behaviors (dissocial personality traits), and psychological instability (depressive symptoms, borderline personality features and self-defeating personality features), adding impulsivity to the items to be analyzed. We hypothesized that impulsivity will tend to associate with the items included in the psychological instability dimension, and specially with depression.

As we wanted to study a homogeneous group of patients, DSM-IV-TR non-purging BN patients were excluded. In addition to the fact that non-purging patients are scarcely represented in clinical samples, the clinical identity of the non-purging subtype of BN as a form of bulimia is nowadays strongly questioned. In fact, the DSM-5 considers the purging subtype as the only clinical form of BN, staying that the non-purging subtype is a form of binge eating disorder, rather than a form of BN. In any case, a diagnosis of purging BN does not imply that the patient does not use fasting and exercise for weight control.

Our results support the initial hypotheses, since impulsivity appeared associated in our sample to depressive symptoms, self-defeating personality traits and borderline personality traits. The obtained model was based on five dimensions which were fully coincident with the dimensions of the initial one. In order to simplify the discussion of the results, we grouped the clinical items into two main categories, which we called eating behavior and personality/psychopathology. The first has to do with eating dysfunction and body dissatisfaction, and incorporates the symptoms which are currently used as diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 and the ICD-10. As in the models proposed by Gleaves and associates,10,11 as well as in our former model,12 body dissatisfaction appears as a core element, being related to restrictive eating behaviors, on the one hand, and with compulsive eating, on the other.

The second category contains non-eating related psychopathological symptoms and personality traits. It includes dissocial personality traits and another component, which can be referred as emotional instability. This is, in our opinion, the main component of the model, and in fact is the factor which explains a greater percentage of the variance. Emotional instability integrates depressive symptoms, impulsivity, borderline personality traits, and self-defeating personality traits, a cluster of symptoms and personality traits which are usually detected in patients with BN. According to some studies from our group, the cluster of items which composed this dimension seems to be capable of differentiating between BN patients and normal controls, from a psychopathological as well as a neurobiological perspective.3,4

Although several studies suggest that depression and BN are independent psychopathological conditions,13 mood disorder has been traditionally associated to BN, in the light of the high prevalence found not only in patients, but also in their first degree relatives.14 In addition, bulimia and affective disorders seem to share some clinical traits.15–17 Mood disorder can either precede or follow the diagnosis of BN, being present in many cases after the remission of the eating disorder. It is difficult therefore to determine whether mood disorder is a risk factor, a co-morbid condition or a consequence of BN.18 One way or the other, the existence of depressive symptoms seem to condition a greater severity of the bulimic symptoms, which improve when antidepressant drugs are used for treatment,19 as well as worse outcome.20

Our results regarding the role of impulsivity are in agreement with numerous studies which stress the relevance of this clinical item in the psychopathology of BN, as well as in other conditions characterized by the lack of control of the individual over his/her behavior. Several studies support the idea that the lower behavioral inhibition found in impulsive subjects can lead to an increase in the severity of eating symptoms when they suffer from BN.7–21 In fact, impulsivity and borderline features have been identified as risk factors for the development of BN.22 As with borderline personality traits, impulsivity has been associated to increased risk for substance abuse and worse outcome.23–25 The association between the diagnoses of BN and borderline personality disorder has also been defended repeatedly in the literature.26–29 Patients with both diagnoses tend to display a pattern of behavior characterized by high impulsivity,26,30,31 and high affective instability,32 impulsivity and borderline symptoms being frequently associated to depressive symptoms26,33 and disturbed interpersonal relationships.27,33 Borderline personality traits seem also to increase the severity of bulimic symptoms and can be seen as factors associated to worse outcome, as they can prolong the duration of the illness and contribute to the persistence of residual symptoms.28,34

We have shown in our study how self-defeating behaviors tended to be associated to depressive symptoms, impulsivity and borderline personality traits. Self-defeating and self-aggressive behaviors have been associated to higher symptom severity and worse outcome in many studies.11,34–37 They can also increase the risk for substance use and misuse38,39 and are frequently associated to higher impulsivity35,40 and distorted interpersonal relationships.

We are aware that our study has some methodological limitations. First, the sample was not too large, but we consider that it consisted of people suffering from severe BN and was very homogeneous from a clinical point of view. Second, our model did not include some clinical elements which have appeared associated to BN and impulsivity in other studies, as for example, harm avoidance, novelty seeking or decision-making processes.40–44 The fact that we started from a previous model conditioned the selection of the variables at the time of designing the study. Finally, it is true that other assessment tools could have been used in the study, but we tried to maintain some continuity between the first and the second model and this fact conditioned the selection of the clinical scales.

In conclusion, although more research is needed,45 the results from our study support the conceptualization of BN as a multidimensional disorder. We can consider that two basic components exist. The first one is related to body dissatisfaction, which can move the subject either to restrict food intake or to purge. The second component, emotional instability, is related to psychopathological items and personality traits that are frequently detected in patients with BN. As has been discussed, there are numerous studies in the literature which support the relevance of the items that make up this component, which in our opinion could be regarded as the “psychopathological core” of BN, so that it is constituted in such a way that it seems to be able to condition the severity and the morphology of the eating-related symptoms, as well as the emergence of other symptoms, as for example substance use. In addition, given that the clinical items of which it is made up have been considered in many studies as prognostic indicators,25 this component may also be able to determine the course and the prognosis of BN.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

FundingThe study has been supported by grant PI060974 (Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica [I+D+I]; Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria. Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Spain), and European Social Fund/Gobierno de Extremadura.

Conflict of interestAuthors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We are grateful to Prof. James McCue for assistance in language editing.

Please cite this article as: Vaz-Leal FJ, et al. Papel de la depresión y la impulsividad en la psicopatología de la bulimia nerviosa. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2014;7:25–31.