We analyse the gender-based violence against women considering the Aymara ethnic ascendance as a casual factor.

Materials and methodsWe applied the Spanish version of the Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA) Scales and Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) on 400 women, who currently live in the region of Arica and Parinacota, Chile.

ResultsThe individuals show that non-physical violence is the predominant behaviour in couples and higher rate of violence is present in women with Aymara ancestry than others.

ConclusionsWe conclude that social constructions of gender may be a risk factor in violence against women because of its influence in social inequalities and abuses of power against women.

Se describe la presencia de violencia de género en mujeres con ascendencia étnica aymara, analizando la presencia de diferencias con mujeres de ascendencia no originaria.

Material y métodosParticiparon 400 mujeres residentes en la región de Arica y Parinacota-Chile. Se utilizó la versión en español de las escalas Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA) y Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).

ResultadosLos resultados evidencian un predominio de violencia no física hacia la mujer en la relación de pareja, hallando diferencias significativas entre las participantes en función de la ascendencia étnica, siendo mayores los índices de violencia en las mujeres con ascendencia aymara.

ConclusionesSe concluye que las construcciones sociales respecto al género presentes en la cultura aymara constituyen un factor de riesgo para la violencia de género, debido a su influencia en la emergencia de asimetrías sociales y condiciones de abuso de poder hacia la mujer.

Gender violence is defined as all abusive actions against women that can bring about physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm, including threats of such actions and coercion or deprivation of liberty.1–4 It is framed in an abusive relationship dynamic, in which the partner exercises power and control; an interaction pattern emerges that produces harm and affects the woman's autonomy and liberty, functioning as means to achieve discipline.2,5,6

Studies by the World Health Organisation (WHO) indicate that between 10% and 69% of women have been physically attacked by their partners at some moment in their lives.7 In Chile, studies at a national level indicated that the police reports of violence within the family have been growing in the last few years, reaching 108,538 reports in 2007; 90.5% of these corresponded to abuse against women.8

The emphasis in the approach to gender violence has been put on the consequences derived from the abuse actions, with the goal of repairing the traumatic experiences.2,3,6,9–15 However, current advances in the matter point out the importance of considering the influence of cultural aspects in the presence of aggression against women, which are barely dealt with in the intervention strategies used by the health services and public policies in Chile.16–18

From a psychosocial viewpoint, gender violence would be inserted in a form of social organisation and in a system of beliefs and cultural values that determine practices, behaviours and styles of relationships between the genders. Consequently, the way that people build social reality is studied, emphasising the setting out of roles and expectations for men and women. These form a catalogue of socially constructed roles, which define the ways of being, feeling and acting.19–23 Within this scenario, the family—as an institution that reproduces culture and transmits values, beliefs, behaviour guidelines and styles of relationships—would be the primary spot where unequal relationships between the genders are expressed, favouring the emergence of abuse in intimate partner relationships.24,25

From this viewpoint, it is interesting to examine the particularities of the Aymara ethnic group. The Aymara are an indigenous people settled in the highland areas in the extreme north of Chile, principally dedicated to activities related to agriculture and livestock. This ethnic group is characterised by a special worldview that limits the relationship between man and woman as a system of complementarity, with the family being the key organisational unit of their culture.26–28

With respect to the family unit, in the Aymara worldview men and women should consolidate as a duality by means of the matrimonial bond called Chacha-Warmi, along with establishing their family unit (represented by the spouses and their descendents), promoting social, cultural and economic reproduction. In this sense, the man and the woman acquire a social position through the prestige that consolidation as a numerous, stable family implies.28,29

Both spouses are considered responsible for the family unit in the family dynamics, assuming the fulfilment of various domestic, commercial and social activities. However, there is a distribution of work based on gender, in which women takes on principally childcare and household chores, lacking participation in the economic and social spheres. In contrast, men dedicate themselves to productive, economic and social activities (due to their condition as head of the household), becoming active agents in the social organisation of their people.26–30 Although asymmetries are evident in the social roles with respect to gender, in the Aymara worldview, women constitute an essential complement that makes the consolidation and permanence of the family unit possible; in turn, this favours reproduction of their culture.30 It is, however, worth considering that this rigidity in schematising sexual roles and functions can generate episodes of abuse against women by promoting situation of abuse and power and of vulnerability.26–29

The characteristics themselves of the Aymara ethnic group and the differences associated with gender roles are part of this people's worldview. They make it necessary to investigate the transmission of cultural patterns and behavioural guidelines that favour the emergence of forms of violence against women, based on the social constructs characteristic of their culture.26–30

Considering that culture and social environment can establish significant differences in the presence of gender violence, our objective was to diagnose the presence of gender violence in women of Aymara ascendancy in the regions of Arica and Parinacota, Chile.

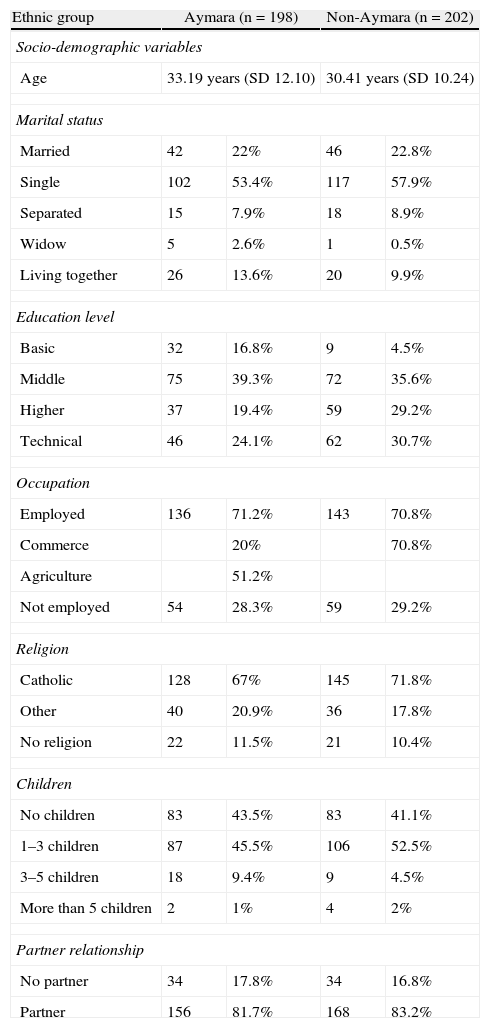

MethodSubjectsThe study included the participation of 400 adult women divided into 2 groups: Aymara ethnic group (n=198) and non-indigenous ethnic group (n=202). We considered the women who described themselves as being Aymara as having Aymara ethnic ascendancy; they constituted 48% of the total sample. The socio-demographic characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of Aymara and non-Aymara women.

| Ethnic group | Aymara (n=198) | Non-Aymara (n=202) | ||

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Age | 33.19 years (SD 12.10) | 30.41 years (SD 10.24) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 42 | 22% | 46 | 22.8% |

| Single | 102 | 53.4% | 117 | 57.9% |

| Separated | 15 | 7.9% | 18 | 8.9% |

| Widow | 5 | 2.6% | 1 | 0.5% |

| Living together | 26 | 13.6% | 20 | 9.9% |

| Education level | ||||

| Basic | 32 | 16.8% | 9 | 4.5% |

| Middle | 75 | 39.3% | 72 | 35.6% |

| Higher | 37 | 19.4% | 59 | 29.2% |

| Technical | 46 | 24.1% | 62 | 30.7% |

| Occupation | ||||

| Employed | 136 | 71.2% | 143 | 70.8% |

| Commerce | 20% | 70.8% | ||

| Agriculture | 51.2% | |||

| Not employed | 54 | 28.3% | 59 | 29.2% |

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 128 | 67% | 145 | 71.8% |

| Other | 40 | 20.9% | 36 | 17.8% |

| No religion | 22 | 11.5% | 21 | 10.4% |

| Children | ||||

| No children | 83 | 43.5% | 83 | 41.1% |

| 1–3 children | 87 | 45.5% | 106 | 52.5% |

| 3–5 children | 18 | 9.4% | 9 | 4.5% |

| More than 5 children | 2 | 1% | 4 | 2% |

| Partner relationship | ||||

| No partner | 34 | 17.8% | 34 | 16.8% |

| Partner | 156 | 81.7% | 168 | 83.2% |

The usefulness of this instrument lies in evaluating the presence of violence against women within the intimate partner relationship. It is composed of 30 items, being divided into 2 subscales: physical violence subscale (8 items that evaluate the presence of physical violence) and the non-physical violence subscale (22 items that evaluate the presence of non-physical violence). The response scale for each subscale corresponds to a 5-point Likert-type scale, which goes from “never” to “very frequently”.

This instrument possesses appropriate psychometric properties, with Cronbach's alpha values of 0.85 and 0.94 for the physical violence and the non-physical violence subscales, respectively.

Short version in Spanish of the “WAST”.32

The usefulness of this instrument stems from the identification of women abused by their intimate partners. It consists of 2 items that ask about the degree of tension and of difficulties existing in the intimate partner relationship. Its response scale corresponds to an agreement scale that goes from: 1=“strongly disagree” to 2=“strongly agree”.

This instrument possesses appropriate psychometric properties, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91.

ProcedureThe criteria for inclusion in the study specified that the participants were adult women of ethnic ascendancy and without ethnic ascendancy, residents of the city of Arica. The following were criteria for exclusion: not being an adult and the presence of any type of sensorial or cognitive disorder.

Before the instruments were administered, the women evaluated received a document indicating the study goals, the fact that participation was voluntary, the confidentiality of their data and the criteria for inclusion. If the woman wished to participate, an informed consent was requested, fulfilling the ethical standards for social science research. After that, we recorded the socio-demographic data and administered the questionnaires in the following order: ISA scale and then WAST questionnaire. The mean time of assessment was approximately 30min. Collaborators administered both instruments in the workplace of the women evaluated.

ResultsThe mean result of the Aymara women in the WAST scale was 1.4 (SD=1.2; range=0–2). The mean result for the women who did not have indigenous ascendancy was 0.84 (SD=0.89; range=0–2). The total score for the scale indicated that 43.5% of Aymara women presented intimate partner violence, 32.7% of non-Aymara women presented intimate partner abuse.

With respect to the forms of violence measured with the ISA, the results corresponding to the Aymara women showed a mean of 5.63 (SD=12.80; range=0–88) in the physical violence subscale and an average of 11.95 (SD=17.04; range=0–107) for the non-physical violence subscale. In contrast, the ISA results for the women lacking indigenous ascendancy showed an average of 2.17 (SD=9.8; range=0–94) in the physical violence subscale and a mean of 6.6 (SD=12.7; range=0–97) in the non-physical subscale.

There were significant differences in the forms of violence measured by the ISA in function of the ethnical ascendancy of the participants. These differences between the Aymara and non-Aymara women appeared in both physical violence (F=0.000) and in non-physical violence (F=0.003). Differences were also found in the Presence of abuse measured by the WAST, based on ethnic group ascendancy (F=0.02).

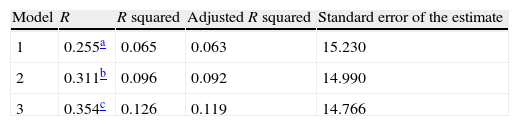

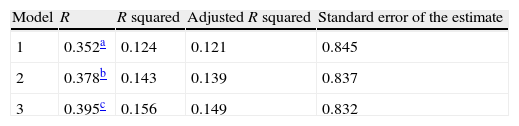

To analyse the relationship between the socio-demographic variables and the dimensions of physical and non-physical violence on the ISA scale, we applied a regression analysis with the successive steps method. Physical violence was related to the variables children, ethnic group, level of education and current partner relationship status. Non-physical violence showed a relationship to the variables children, ethnic group and current partner relationship status. In turn, Presence of abuse using the WAST instrument was related to the variables current partner relationship status, level of education and marital status (Tables 2–4).

Regression coefficients for the presence of physical violence as measured on the ISA scale.

| Model | R | R squared | Adjusted R squared | Standard error of the estimate |

| 1 | 0.230a | 0.053 | 0.051 | 11.130 |

| 2 | 0.274b | 0.075 | 0.070 | 11.014 |

| 3 | 0.299c | 0.089 | 0.082 | 10.942 |

| 4 | 0.319d | 0.102 | 0.093 | 10.879 |

Dependent variable: presence of physical violence (ISA scale).

Regression coefficients for the presence of non-physical violence as measured on the ISA scale.

| Model | R | R squared | Adjusted R squared | Standard error of the estimate |

| 1 | 0.255a | 0.065 | 0.063 | 15.230 |

| 2 | 0.311b | 0.096 | 0.092 | 14.990 |

| 3 | 0.354c | 0.126 | 0.119 | 14.766 |

Dependent variable: presence of non-physical violence (ISA scale).

The subjects constituting the sample analysed in this study presented a predominance of non-physical violence, principally in reference to psychological abuse, measured as control and threats from the partner. This is associated with significant sequelae in the victims’ physical, emotional and sexual health, affecting their subjective well-being.25,33

Likewise, the participants presented high rates of physical violence, in reference to the presence of blows and sexual aggressions, both also associated with deterioration in health and well-being. Although types of violence against women were found, these tended to coexist in the intimate partner relationship, linked to the repetition of a behavioural pattern called cycle of violence. This behaviour is characterised by the fact that the victim continues to live with the abuser, in an alternating succession of violent episodes followed by reconciliation, which progress in a spiral of ever greater violence.2,9,11,33,35

With respect to the existence of significant differences in the presence of violence between Aymara and non-Aymara women, higher rates of both physical and non-physical abuse were found in the former. It would be good to consider whether these differences are related to the rigidity of the gender-role sexual differentiation present in the Aymara worldview that attributes authority to the man in the social and family spheres, placing the women in conditions of vulnerability.26–30

As to the influence of psychosocial factors in the presence of violence against women, the results make it clear that the abuse episodes are strongly related to the level of education, child care, the status of the current intimate partner relationship and ethnic ascendancy.33–35 With respect to the level of education, there is evidence that a higher educational level is associated with greater opportunities for work, support networks and spaces for interaction outside the family dynamics. All of these favour the woman's independence and personal autonomy, as they operated as media that facilitate the rupture of the circles of violence.2,33,35 Turning to the upbringing of children, this is associated with the presence of abusive actions; this is due to the fact that the woman continues to live with the intimate partner based on the absence of the economic means needed to take on the care of the home, so the episodes of abuse perdure.33,36,37

It can be seen that the ethnic group variable shows significant associations with both physical and non-physical violence. This is explained by the influence played by the cultural patterns and the forms of social and family organisation characterising the Aymara ethnic group in the emergency of asymmetrical interactions between the genders, which make the acts of abuse against women possible.36–38 There is evidence that the greater the rigidity in the demarcation of the sexual roles and functions, the greater the risk of episodes violence against women in intimate partner relationships.30,36,37

Our results highlight the importance of considering the influence of cultural aspects and social constructs in the presence of abusive actions against women.39–41 Specifically, in the case of the Aymara ethnic group, few studies have been carried out on the situation raised; multidisciplinary studies are needed, which will make it possible to conceptualise the phenomenon of gender violence from the worldview of this ethnic group itself.30,37

Despite the interest of the data supplied, this study has certain limitations: (1) the difficulty in contacting women of Aymara ascendancy; (2) some of the women (10%) did not agree to take part in the study during our data collection (the sensitivity of the subject to be treated probably influenced their willingness to participate); and (3) the limited number of measurement instruments for collecting data validated in the local context.

Future studies should centre their research on the construction of gender identity characteristic of the Aymara culture and its influence in the assimilation of abusive practices within the relationship dynamics in function of the gender-assigned social roles, designing new modalities of prevention and intervention.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or animals were carried out for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis study was funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID): Project A/027816/09.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

This study was carried out in the Interdisciplinary Unit of Legal and Psychosocial Research at the Department of Philosophy and Psychology, with the support of the Universidad de Tarapacá-Mineduc Performance Agreement.

Please cite this article as: Zapata-Sepúlveda P, et al. Violencia de género en mujeres con ascendencia étnica aymara en el extremo norte de Chile. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2012;5:167–72.