Low-energy osteoporotic pelvic fractures in the elderly are a very common problem. They are usually stable fractures, non-life threatening and only require conservative treatment.

The pelvic bone structure is closely related to important vascular structures. The Corona Mortis, located in the retropubis, has an important anastomotic value as it serves as communication between the internal and external iliac vessels.

The case is presented of an 87-year-old woman, who, after a casual fall, was diagnosed with an osteoporotic fracture of the left pubic rami associated to a lesion of the Corona Mortis, which led to a severe picture of hemodynamic instability.

After angiography with supra-selective embolization of the lesioned vessel, and the transfusion of several haemoderivatives, the patient progressed satisfactorily, and was discharged after a few days.

La fractura osteoporótica de pelvis del anciano por baja energía es un proceso muy frecuente. Habitualmente son fracturas estables, no suelen suponer un riesgo vital y, únicamente precisan de tratamiento conservador.

La estructura ósea pélvica tiene relación de proximidad con importantes estructuras vasculares. La Corona Mortis, de localización en el retropubis, posee un importante valor anastomótico ya que constituye una comunicación entre el sistema de los vasos ilíacos internos y externos.

Presentamos a una mujer de 87 años, que tras una caída casual fue diagnosticada de fractura osteoporótica de las ramas pubianas izquierdas asociada a la lesión de la Corona Mortis, lo que provocó un grave cuadro de inestabilidad hemodinámica.

Tras una angiografía con embolización supraselectiva del vaso lesionado y a la transfusión de varios hemoderivados la paciente evolucionó satisfactoriamente siendo dada de alta a los pocos días.

Osteoporotic pelvic fractures in elderly patients are frequent processes in Orthopedic Surgery Services, since about 80 cases per 100,000 elderly occur every year, with superior (iliopubic) ramus fractures being by far the most common (26 cases per 100,000 elderly per year).1 These fractures without disruption of the posterior ring are stable and do not normally pose a threat to the life of patients, thus being treated conservatively with analgesia, thromboprophylaxis and early mobilization.2

The pelvic bone structure is closely related to major vascular structures whose injury, although rare, is possible in these fractures and may cause severe hemorrhages which endanger the life of the patient.

We present the case of an elderly patient in whom a low-energy trauma caused a stable fracture of the pelvic rami, associated with severe intrapelvic hemorrhage by vascular lesion which threatened her life.

Case reportThe patient was an 87-year-old female who attended our Emergency Department following an accidental fall at her home. She was allergic to penicillin and derivatives, presented a medical history of chronic venous insufficiency, peptic ulcer, hiatal hernia, arterial hypertension, positive hepatitis C virus and gallstones.

The patient reported pain and functional deficit at the level of the left hemipelvis and lower limb, with normal abdominal clinical examination and vital constants within normal limits.

An osteoporotic fracture of the left ilium and pubic branches, without displacement, was diagnosed by simple anteroposterior pelvic radiography (Fig. 1). The patient was admitted at our department for follow-up, and conservative treatment was indicated. Blood tests performed upon admission showed a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 13.9g/dl and a hematocrit (Hct) level of 42.1%.

At 12h of admission, the patient presented a respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute, tachycardia of 110 beats per minute, hypotension (80/47mmHg), mucocutaneous pallor, signs of dehydration and drowsiness. Her abdomen was distended, spontaneously painful on palpation and with decreased peristalsis. We obtained an abdominal radiograph which showed air distension, as well as a new analytical study which reported Hb values of 8.3g/dl and Hct of 25%. Due to the sharp decline of these values, the hemodynamic impact and the existing abdominal symptoms, we started treatment through absolute diet, two transfused packed red blood cells and observation. The vital signs returned to normal values, with post-transfusion blood test values reflecting Hb 10.4g/dl and Hct 30.9%.

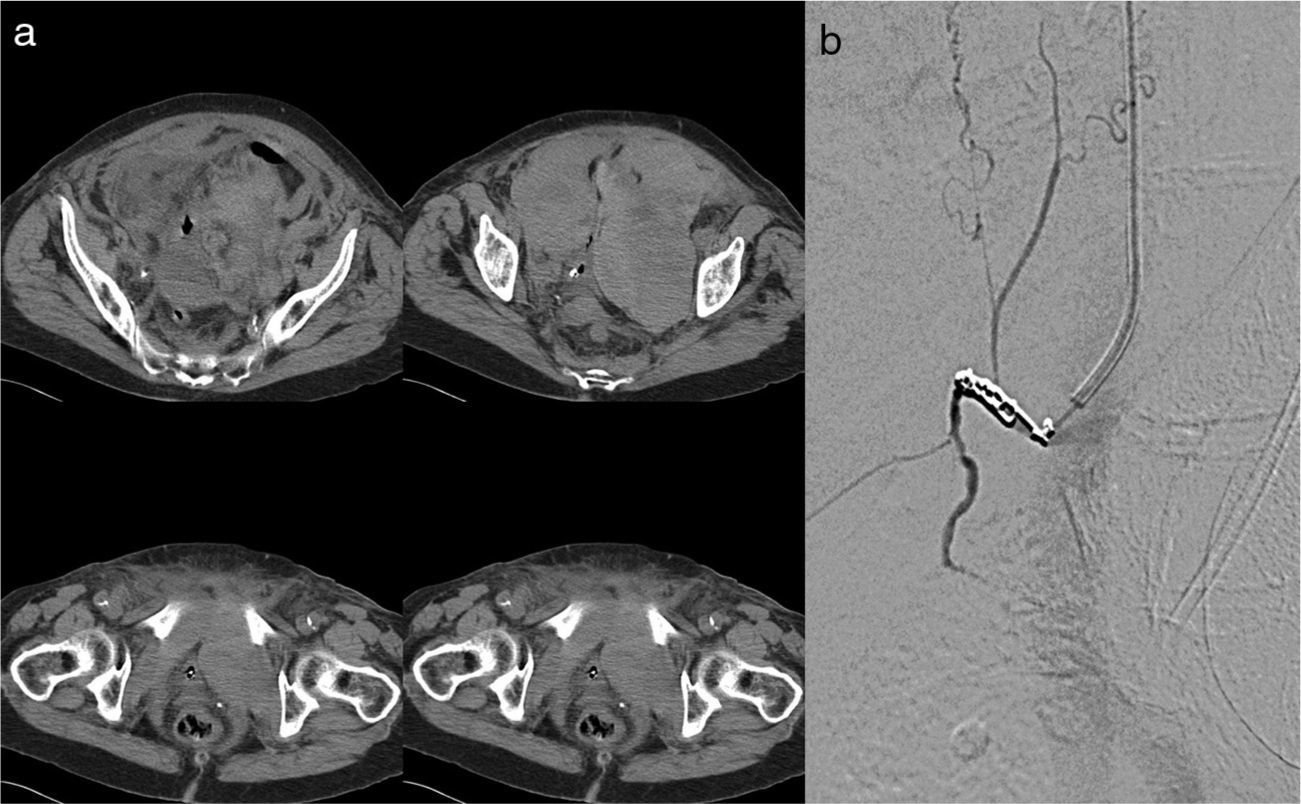

Within 24h the patient presented renewed and progressive hemodynamic instability, with Hb values of 5g/dl and Hct of 17%. We performed an abdominopelvic ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scan without intravenous contrast which confirmed the presence of a 15cm×10cm retroperitoneal hematoma compressing adjacent structures, including the bladder, and affecting the anterior and posterior pararenal fascia, as well as the posterolateral abdominal muscles. The posterior arch of the pelvis was intact and without fracture (Fig. 2a).

(a) Images from an abdominopelvic CT scan showing the different axial sections of a bilateral retroperitoneal hematoma measuring 10cm×15cm. (b) Supraselective angiography of the external iliac artery and the left and right hypogastric arteries with embolization through three microcoils.

This hematoma presented no criteria for immediate surgical indication, so we proceeded to transfuse a further two packed red blood cells. We also obtained a selective angiography of the external iliac artery and the left and right hypogastric arteries which highlighted bleeding of the pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery, which was embolized using three microcoils (Fig. 2b). In the immediate postoperative period we conducted a new transfusion of three packed red blood cells.

During the rest of her admission, the patient presented symptoms of metabolic acidosis with decompensated heart failure secondary to a complete arrhythmia by atrial fibrillation, hypertension and volumetric overload with scarce bilateral pleural effusion. She recovered from these processes progressively within 10 days, after which she tolerated a sitting position and was discharged from hospital. Blood analysis values during the days following therapeutic embolization remained normal and stable.

The patient has attended outpatient reviews regularly, being permanently discharged within 3 months of the fracture.

DiscussionWhen orthopedic surgeons consider studying pelvic fractures, they refer to those caused by high energy trauma, due to the severity involved and the technical difficulty of their treatment. Osteoporotic pelvic fractures are scarcely studied and are given little importance, as they are usually stable fractures which do not require surgical treatment, with good prognosis in terms of fracture healing, and where the therapeutic goal is pain control and early mobilization of patients. For these reasons, the literature on this topic is scarce, almost always referring to the epidemiology and frequency, without assigning more importance to specific treatment. However, the mortality figures which have been published are similar to those occurring in hip fractures among elderly patients. These figures are surprising given the characteristics of the fracture and the conservative treatment applied. Such high mortality figures reflect possible complications, usually vascular, which could go unnoticed and which would endanger the lives of patients, mainly due to the deteriorated clinical characteristics that these patients already present in many cases,3,4 or else the frequent association of a fracture of the posterior arch in up to 90% of the cases, which would go unnoticed in most patients.5,6 This was not the case with our patient.

Performing an immediate CT scan is recommended7 after a pelvic fracture associated with anemia or hemodynamic instability. In our case, this test was performed without contrast, so it could not detect the presence of active bleeding.

Once the hematoma was diagnosed, we established that urgent surgery was not indicated,8 since it did not present associated intraabdominal hemorrhage, perineal wound, gastrointestinal perforation, pulsating or rapidly expanding hematoma, there was no loss of inguinal pulses and no injuries to the bladder or urethra.

However, given the situation of two repeated episodes of anemia, we decided to perform an angiography,7 which enabled us to identify the site of active bleeding and perform the corresponding therapeutic embolization.

Following a pelvic fracture, in cases presenting severe and/or potentially lethal arterial bleeding, the most commonly affected arteries are usually the internal iliac and/or its branches. In order of increasing importance, we find the inferior gluteal, inferior vesical, obturator, iliolumbar and the sacral arteries.9 Performing an angiography followed by supraselective embolization of the affected branches has been established as the treatment of choice in these cases, given their minimally invasive characteristics.1,3,10

Corona Mortis is an anatomical variation consisting of a vascular anastomosis which may be arterial, venous or arteriovenous. Its name, which literally means “crown of death”, is derived from the fact that the injury is frequently associated with severe hemorrhage. This anastomosis generally occurs between the obturator vessels and the inferior epigastric artery. There is considerable variability in the origin of the obturator. In most cases it is a branch of the internal iliac artery, whereas the inferior epigastric artery leaves the external iliac on the inguinal ligament.1,3,11–13 According to Pick et al.,14 in 70% of cases, the obturator artery originates directly from the internal iliac, in 28% of cases it originates from the external iliac as a branch of the inferior epigastric and only in 2% does it originate directly from the external iliac. Rusu et al.15 elaborated a classification based on the vessels which participated in Corona Mortis to facilitate the knowledge of its morphology and topographic possibilities for surgeons, given its potentially harmful characteristics. It is usually located in the retropubis at the level of the superior pubic ramus and at a variable distance from the symphysis (40–96mm).3,11,12,16 Its existence ranges between 30% and 43% of the general population according to different authors,3,12,16,17 with the incidence of purely arterial anastomosis being 10–43% and that of venous anastomosis of approximately 60%.16,17

Its involvement during endopelvic or inguinal surgery or surgery due to fractures of the acetabulum or the pelvis, as in the present case, can cause dangerous hemorrhaging. Clinically, the signs which may lead to suspicion of the injury are hematomas, edema and abdominal pain in the groin and perineum.

In the case of surgeries, its location and subsequent preventive ligation of vessels are vital, because once it appears it is difficult to control due to its retraction through the obturator orifice of the pelvis.13 This severe risk has led some authors to suggest preventive embolization in patients with major pelvic trauma.18

ConclusionsAs an anatomical variant, Corona Mortis is an important communication between the system of internal and external iliac vessels, and may be bilateral or not.

In osteoporotic pelvic fractures, this rare but possible injury will produce hemodynamic instability and, if not adequately controlled, could even cause death. Therefore, it should be taken into account as a potential risk factor in these fractures.

It is especially important to conduct a careful hemodynamic monitoring of elderly patients with stable pelvic fractures during the first 24h due to the risk of hemorrhage. If there is a rapid deterioration of the vital constants, it is necessary to perform a CT scan and, if necessary, an angiography of the iliac arterial trunks, seeking a vascular injury and performing a selective embolization of the damaged artery. This vascular complication, although rare, may appear with stable fractures of the anterior arch of the pelvis in elderly patients, and may even endanger their lives.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FinancingThe authors declare that they have not received any kind of financing for the elaboration of this work.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Palacio J, Albareda J. Hemorragia severa secundaria a fractura osteoporótica de la pelvis: a propósito de un caso. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:192–195.