Elbow replacement or arthroplasty is a good therapeutic option for a large percentage of patients with significant joint destruction. However, many orthopaedic surgeons are not familiar with the surgical approaches or techniques associated with elbow replacement implants. Furthermore, the incidence of complications is higher than in other joint replacements, the most important being infections, mechanical failure, cubital neuropathy, and problems with the triceps. For these reasons, the use of bone arthroplasty in Spain may be less than ideal. Although, inflammatory arthritic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are the most frequent indication for this operation, distal humerus fractures and post-traumatic disease are a growing indication. This work attempts to summarise the most important current concepts associated with elbow replacement.

La artroplastia de codo representa una buena alternativa terapéutica para un gran porcentaje de pacientes con importante destrucción articular. Sin embargo, muchos cirujanos ortopédicos no están familiarizados con los abordajes o técnicas quirúrgicas relacionados con la sustitución protésica del codo. Además, la incidencia de complicaciones es superior a la de la artroplastia de otras articulaciones, siendo las más importantes, la infección, el fracaso mecánico, la neuropatía cubital y las alteraciones del tríceps. Por estos motivos, la utilización de artroplastia de codo en el medio español puede que sea inferior a la ideal. Aunque las artropatías inflamatorias, como la artritis reumatoide, constituyen la indicación más frecuente para este tipo de intervención, las fracturas de húmero distal y la afección postraumática representan una indicación creciente. Este trabajo intenta resumir los conceptos actuales más importantes relacionados con la artroplastia de codo.

Joint replacement surgery represents a major advance in the field of Orthopaedic Surgery. The elbow joint has a number of characteristics which differentiate it from other joints such as the hip or knee, in terms of joint replacement surgery. It is a relatively smaller joint whose stability depends largely on ligamentous structures. Therefore, elbow arthroplasty presents greater risk of mechanical failure (especially due to polyethylene wear) and instability.

There are several additional factors which increase the complexity of elbow arthroplasty, such as the need to approach the elbow through the extensor apparatus, the existence of an increased incidence of infection, the as yet undefined role of radial head replacement and the possibility of developing ulnar neuropathy regardless of intraoperative management of the ulnar nerve. There are still many aspects to be developed in the field of elbow arthroplasty, such as the role of alternative friction surfaces to polyethylene, the development of effective uncemented components, the use of navigation for a more precise implantation of components, partial arthroplasties and development of improved review systems.1

DesignsTypes of implantAt present, most orthopaedic surgeons agree in classifying implants as linked (hinged) or unlinked (non-hinged) (Fig. 1). Linked implants are characterised by a physical connection mechanism between the ulnar and humeral components, which allows or prevents subluxation or dislocation, whilst unlinked implants do not have such a connection. In general, linked implants have a greater degree of constriction. However, some unlinked implants present more constriction than linked implants. Most currently existing linked implants are semiconstricted, which means that there is some degree of varus-valgus and rotational laxity. In theory, this degree of semiconstriction reduces tensions in the implant-cement–bone interface, thus decreasing the possibility of loosening of the components. At present, there are some designs that allow intraoperative selection of linked or unlinked implants, such as the Latitude® design.

Some characteristics related to the design of elbow joint implants have been shown to improve their survival. The majority of currently existing implants consist of rods which are inserted into the medullary canals of the humerus and ulna and are then fixed with acrylic cement, although certain components, such as the humeral Kudo-iBP component, seem to provide a good cementless fixation. Several of the humeral components currently used consist of an anterior flap, which seems to improve their anteroposterior and lateral intraosseous stability. The type of coating of the components is clearly related to their survival. In the case of Coonrad–Morrey arthroplasty, the generation of ulnar components with an acrylic cement pre-coating has been associated with an increased incidence of osteolysis and mechanical failure. Absence of a porous coating in other designs also appear to be associated with a higher incidence of mechanical failure.

Advantages and disadvantages of linked and unlinked componentsThe results and survival of each specific type of linked or unlinked component cannot be extrapolated to other types of implant in the same family. However, there are a series of general advantages and disadvantages which are inherent to linked and unlinked components.

Linked components ensure elbow stability, even in case of severe ligament failure or bone loss. These implants do not only eliminate the main complication of unlinked implants, instability, but also enable a wider release of soft tissues, in order to correct angular deformities and increase mobility. Their main disadvantage is the high transmission of tensions to the implant interface, which can lead to loosening. Semiconstricted components appear to be associated with a relatively low rate of loosening, but also present some risk of accelerated polyethylene wear, especially in the presence of angular deformities and soft tissue imbalance.

Some linked components enable prosthetic replacement in situations of severe bone loss, whereas most unlinked components require integrity of the humeral columns and the greater sigmoid cavity. Linked implants are also very useful in patients with high flexion contracture, which requires the non-anatomical implantation of the components in order to restore a functional range of motion.

The main advantages of unlinked implants are reduced invasion of the medullary canal through the use of shorter rods, the possibility of using the humeral component as hemiarthroplasty in some cases and increased theoretical survival of the components if an anatomical implantation with a perfect range of motion is achieved.

At present, the reports published seem to favour the use of linked implants. Little et al. published a systematic review of the literature published until 2003.2 Although the incidence of review surgery was similar (11% vs 13%), linked components presented a lower incidence of radiographic loosening and greater mobility in extension. In the only study comparing the survival of linked and unlinked implants, Levy et al. reported higher rates of review surgery with unlinked components.3

Indications and contraindicationsInflammatory arthropathies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, constitute a classical indication for elbow prosthesis (Fig. 2). Patients with advanced degrees of joint destruction (Mayo Clinic grades III to V)4,5 experience a clear improvement in pain, mobility and function. Furthermore, due to the polyarticular nature of these diseases, the level of activity of patients is limited, thus reducing the incidence of mechanical failure of the implant.

The high success rate of elbow arthroplasty in inflammatory arthropathies has led to the expansion of its indications to other conditions. Posttraumatic elbow osteoarthritis is one of the most difficult processes to treat. Although elbow arthroplasty provides good results in terms of pain and mobility in these cases, patients are usually younger and more active, thus leading to an increased risk of wear and loosening.

At present, elbow arthroplasty is considered an ideal alternative in certain patients with fractures and nonunions of the distal humerus.6–8 In elderly patients with prior joint disease or severe osteopenia it is difficult to obtain a stable osteosynthesis. Other indications for elbow arthroplasty include severe intrinsic rigidity, large bone defects after severe trauma or tumour resection, haemophilic arthropathy and, only rarely, primary elbow osteoarthritis, which usually responds well to joint debridement.

Surgical techniqueApproachDespite the relatively long history of elbow arthroplasty, there is still some disagreement concerning the surgical approach and management routes of the ulnar nerve. At our centre, the vast majority of elbow arthroplasties have been typically associated with ulnar nerve transposition. However, a relatively high percentage of patients develop ulnar neuropathy. There is some interest regarding the possibility of carrying out an in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve without transposition, in order to prevent nerve devascularisation. However, so far there is no firm scientific foundation supporting either option.

With respect to the management of the extensor apparatus, all approaches which carry out triceps detachment lead to weakness in extension in some percentage of patients. In some cases it is possible to conduct the intervention by working on both sides of the triceps.9,10 This approach is especially indicated in patients with distal humerus bone defects (severe trauma, tumours, review surgery), as well as fractures and nonunions of the distal humerus, a situation in which the distal fragments are resected.

In many cases it is extremely difficult to perform the procedure with an intact extensor mechanism. Currently, the most popular procedures are the approach described by Bryan and Morrey,11 division of the triceps at the medial line, and the modifications in the approach of Van Gorden, with detachment of the extensor apparatus at the myotendinous junction.12 At present, there is not enough evidence in the published literature which clearly favours any of these approaches, compared with the others (Fig. 3).

Repair techniques and postoperative protection of the triceps represent 2 fundamental aspects related to the approach procedure. The repair must be performed meticulously and, more specifically, transosseous sutures must be used in the Bryan–Morrey and tricipital division approaches. Avoiding extension against resistance during the first 6 postoperative weeks is generally recommended.

Bone preparation and insertion of componentsNaturally, bone preparation for implantation of an elbow arthroplasty is specific for each type of implant. As a general rule, implants require careful preparation of the medullary canals, as well as creating bone cuts to accommodate the morphology of the articular portion of the implant. Preparation of the ulnar canal can be particularly difficult in patients with small skeletons.

Most currently used implants are fixed with acrylic cement. Given the high incidence of infection in elbow arthroplasties compared with other joints, we recommend the routine use of antibiotic cement. It is important to use cement restrictors, not only to improve cementing quality, but also to avoid the need to extract large quantities of cement in case of infection, as well as to leave space for a shoulder prosthesis in case this is required in the future. It is also important to achieve good apposition of the anterior flap of the humeral component with respect to the anterior humeral cortex or interposed graft, depending on the design employed and local bone morphology.

In cases of marked preoperative loss of mobility, soft tissue release may be insufficient to reestablish a suitable arc. In such cases, it may be necessary to insert the components in a non-anatomical position (a deeper insertion of components in both the humeral side and the ulnar side), thus eliminating any source of bone conflict.

Postoperative managementThe objectives of the first phase of postoperative treatment are to reduce oedema and facilitate full healing of the surgical wound. The operated elbow should be kept extended and elevated for a couple of days before starting active assisted mobility. When using linked prostheses, it may be necessary to keep the elbow immobilised for longer in order to protect the ligamentous structures. In elbows in which the extensor apparatus has been disinserted, it is important that the patient avoids active extension against resistance during the first 6 weeks.

Polyethylene wear seems to be the main factor limiting the longevity of current elbow prosthesis designs. In general, heavy lifting with the operated limb should be avoided. Empirically, it is best not to lift more than 5kg, especially in a repeated manner.

ResultsChronic inflammatory arthropathiesThere are several studies on the results of elbow arthroplasty in cases of chronic inflammatory arthritis, using both linked and unlinked implants. Gill and Morrey published the results obtained in 78 rheumatoid elbows operated consecutively using Coonrad–Morrey arthroplasty.4 At the end of the follow-up period, 97% of patients reported no pain or mild pain and the mean range of motion was 28° extension and 131° flexion. The main complications reported were deep infection (2 elbows), loosening (2 elbows), triceps avulsion (3 cases), periprosthetic fractures (2 cases) and fracture of the ulnar component (1 case). Review-free survival was 92.4% at 10 years. Gschwend et al. published the results obtained with GSB III prostheses in 65 elbows, of which 31 were rheumatoid,13 with a mean follow-up period of 10 years. They obtained good clinical results in most cases and the main complications were infection (6%), loosening (4.6%) and failure of the link mechanism (13.6%).

Other authors have published the results obtained with linked prostheses. van der Lugt et al. published the results of 204 rheumatoid elbows using a Souter-Stratchlyde design14 and with a mean follow-up period of 6.4 years. In this series, only 6 patients reported pain at rest and the main complications were infection (10 elbows), humeral loosening (22 elbows) and dislocation (4 elbows). Kudo et al. published the results in 43 elbows followed for 3 years, with good or excellent results in 86% of cases.15

The overall experience at the Mayo Clinic with the Coonrad–Morrey prosthesis has recently been reviewed. The series includes a total of 461 arthroplasties with a mean follow-up period of 8 years (range: 2–25 years). Approximately 90% (418) of the implants did not require review, 2.2% were reviewed and resected due to infection, 5.4% due to loosening and 1.7% due to polyethylene wear. Three patients required osteosynthesis of periprosthetic fractures and 17 required debridement due to deep infection, with the overall rate of infection being 5.8% (Fig. 4).

TraumaPosttraumatic osteoarthritisThis is one of the most common disorders of the elbow joint, as well as one of the most difficult to solve. In patients with symptoms which are clearly related to the articular surface, elbow arthroplasty provides more predictable results in terms of both pain and mobility. However, it is also associated with a relatively high rate of mechanical failure, especially in young patients.

Schneeberger et al. published their results with 41 elbows using the Coonrad–Morrey prosthesis for the treatment of posttraumatic osteoarthritis.16 The mean age of patients at the time of surgery was 57 years (range: 32–82 years) and the mean follow-up period was 5 years. In total, 73% of patients experienced improvement in pain and the overall results were considered satisfactory in 83% of cases. Nevertheless, the incidence of complications was 27%.

Current experience at the Mayo Clinic was recently updated by Throckmorton et al.17 This work collected 84 arthroplasties, of which 69 were followed for a mean period of 9 years. Approximately 20% of implants failed due to polyethylene wear (8 elbows), infection (4 elbows), fracture of components (3 elbows) and loosening (2 elbows). Out of these failures, 75% occurred in patients younger than 60 years at the time of surgery. The results were considered good or excellent in 68% of elbows and 15-year survival was 70%.

The relatively high incidence of mechanical failure in elbow arthroplasties in patients with posttraumatic osteoarthritis has represented the main reason for the development of new implants, which in theory should reduce the incidence of mechanical failure (Fig. 5). However, there are no published studies on the outcome of the new generations of implants.

Distal humerus fracturesOsteosynthesis is the treatment of choice for most distal humerus fractures. However, in elderly patients with previous joint disease, arthroplasty may be a better alternative, especially in the presence of osteopenia and/or severe articular comminution.

There are different philosophies regarding the surgical technique for performing elbow arthroplasty in patients with acute fracture of the distal humerus. The most widely accepted option is to approach the fracture zone on both sides of the triceps, resect the fractured fragments and implant the components. Resection of the fractured fragments involves detachment of the medial and lateral ligamentous complexes, thus making it necessary to use linked components. Interestingly, resection of the condyles does not seem to affect hand gripping strength or elbow strength in any plane.18

The results of total elbow prosthesis in selected patients with distal humerus fractures are satisfactory. Kamineni et al. published the results of a consecutive series of 43 elbows7 with a mean follow-up period of 7 years. In this series, the majority of patients achieved satisfactory results, with a mean flexion-extension range of 24°–131°. However, 9 patients required reoperation, including 5 reviews of components. McKee et al. published the only prospective randomised trial comparing arthroplasty and osteosynthesis.8 Patients treated with arthroplasties experienced a more rapid functional improvement and a lower incidence of reoperation (12% vs 27%).

Distal humerus pseudoarthrosisSelected cases suffering lack of distal humerus consolidation also represent a good indication for elbow arthroplasty. As in the case of acute fractures, arthroplasty is particularly indicated in elderly patients with osteopenia, previous joint disease or severe bone loss. Morrey and Adams published their initial experience obtained in 36 patients with a mean age of 68 years and followed for a mean period of 4 years.19 Satisfactory results were achieved in 86% of cases and complications included infection in 2 elbows and polyethylene wear in 3 elbows. The experience at the Mayo Clinic has recently been published by Cil et al.6 A total of 92 elbows were followed for a mean period of 6.7 years. Of these, 79% of patients reported no pain or mild pain, with a mean mobility range of 22°–135°. Observed complications included loosening (16 elbows), fracture of components (5 elbows), deep infection (5 elbows) and polyethylene wear (1 elbow).

Other indicationsThere are some selected publications on the results of elbow arthroplasty in patients with severe rigidity or ankylosis,20 dysfunctional instability secondary to severe bone defects,21 haemophilic arthropathy22 and reconstruction after tumour resection.23

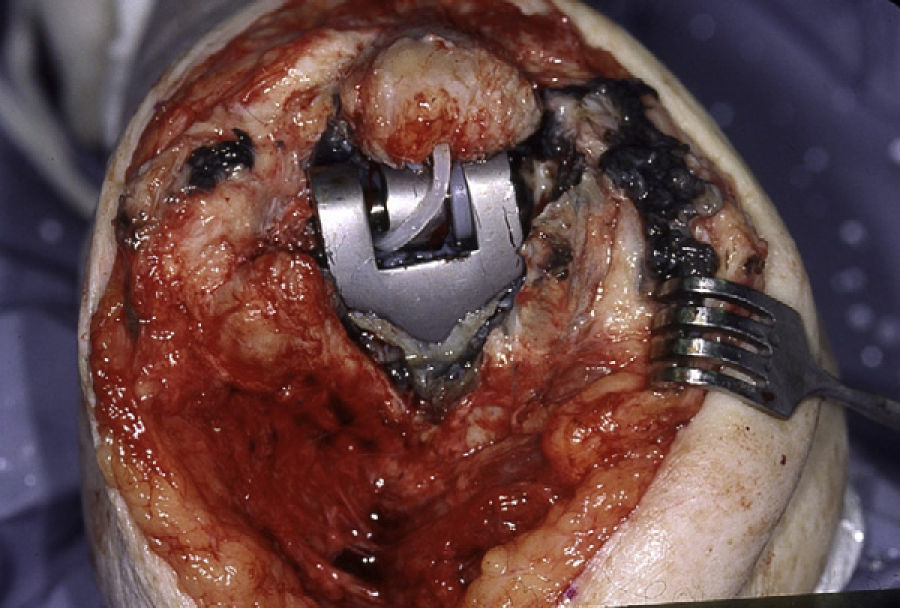

ComplicationsInfectionThe incidence of periprosthetic infection is more common in the elbow than in other joints. This is due to a combination of factors, including fragility of the soft tissues around the elbow joint, the presence of some degree of immunosuppression in patients with inflammatory arthropathy and the possibility of contamination during prior surgeries in the case of traumatic conditions. The current incidence of infection is estimated at between 3% and 4%.24 As mentioned previously, it is advisable to use cement with antibiotics routinely in order to reduce the incidence of infection. Acute infections can be treated by debridement, polyethylene replacement and retention of the components.24 In chronic infections, in many cases it is preferable to carry out reimplantation in 2 times or resection (Fig. 6), depending on the nature of the infection, the needs of the patient and the condition of the remaining bone and soft tissues.25,26

Ulnar neuropathyThe true incidence of ulnar neuropathy is difficult to know, since very probably many of the published studies do not accurately reflect the incidence of purely sensory symptoms. The incidence of severe ulnar neuropathy is probably around 5%.2 Although subcutaneous transposition at the time of elbow arthroplasty is classically recommended, additional studies are required in order to better understand the optimal management of the ulnar nerve during surgery.1

Dysfunction of the extensor apparatusThe true incidence of extensor apparatus dysfunction is also difficult to analyse in the published literature. In the systematic review published by Little et al., the incidence of triceps dysfunction was 3%.2 In the study by Celli et al., approximately 2% of elbow arthroplasties required reoperation due to triceps dysfunction.27 Patients with symptomatic dysfunction of the extensor apparatus may improve through direct repair techniques, anconeus rotational flaps or reconstruction with Achilles allografts.27,28

InstabilityUnlinked elbow arthroplasties may suffer subluxation or dislocation. The incidence of dislocation is about 5%, whilst that of combined subluxation and dislocation is approximately 15%.2 Although there have been reports of attempts at closed reduction and immobilisation, in most cases it is necessary to resort to review surgery and implantation of linked components.

Mechanical failureThe overall incidence of loosening in elbow arthroplasties probably varies between 5% and 10%, and is different depending on the type of implant. According to the systematic review conducted by Little et al., the reported incidence of aseptic loosening is 2% in the case of the Coonrad–Morrey prosthesis, 8% in the case of the Souter prosthesis and 18% in the case of the Kudo prosthesis.2 There are other forms of mechanical failure, including polyethylene wear, osteolysis, component fracture and disassembly of components, whose real incidence is difficult to estimate. Polyethylene wear is probably the mechanism responsible for failure, in the medium and long term, of elbow arthroplasties in young and active patients.17

Periprosthetic fracturesPeriprosthetic fractures are classified according to the location of the fracture, the condition of component fixation and the need to use special techniques for bone reconstruction.29,30 In general, humeral condylar fractures can be treated conservatively, as long as they do not affect the stability of unlinked prostheses. By contrast, most other fractures require osteosynthesis and/or review surgery.

Future outlookNecessary improvements in the field of elbow arthroplasty in the near future are likely to offer more options for implants, a more accurate placement of the components, better stability of unlinked components, improved friction surfaces to reduce wear, better preservation of extensor apparatus integrity and reduction of the incidence of infection.1

There is considerable interest in the development and use of partial prostheses. Most current experience has focused on distal humerus partial arthroplasties and capitellum arthroplasties. Perhaps, coronoid prostheses and proximal ulnar prostheses will also be developed in the future. There have been some laboratory tests with navigation for component implantation. However, for the moment, the limiting factor appears to be the variability of the joint segment with respect to the medullary channels.31

ConclusionsThe field of elbow arthroplasty continues to experience significant progress. At present, elbow arthroplasty represents a good therapeutic alternative for patients with inflammatory processes, as well as for certain patients with posttraumatic osteoarthritis, elderly patients with distal humeral fractures, distal humeral nonunion, certain cases of ankylosis, haemophilic arthropathy and reconstruction following tumour resection. Some linked arthroplasty designs appear to be associated with better results and enable the management of a greater variety of pathologies. There is great interest in developing improved designs which reduce polyethylene wear and mechanical failure in young and active patients.

Success in elbow arthroplasties depends largely on the knowledge by the surgeon of elbow anatomy and surgical approaches, as well as the proper selection and implantation of components and adequate postoperative management. Although, in some cases, elbow arthroplasty is the only viable treatment option, it is important to understand that this procedure is associated with a relatively high rate of complications which can sometimes be extremely difficult to resolve.

In a relatively near future there will probably be cementless implants which can be implanted accurately, perhaps through computer-assisted surgery and navigation. Moreover, we need to have a better understanding of the management of the ulnar nerve and the extensor apparatus, as well as of the role which alternative friction surfaces can play in the field of elbow arthroplasty.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this study does not reflect any patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this study does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mora Navarro N, Sánchez-Sotelo J. Artroplastia de codo. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2012;56:413–20.