The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic was declared in March 2020. This disease affects the respiratory system, and shown high rates of morbidity and mortality during 2020 and 2021. Neurological compromise and increased rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and substance abuse have also been described. Public health policies to prevent COVID-19 infection, decrease in control and monitoring of mental illness, and social and economic impact may have contributed to the increase in suicidal ideation and suicides. It is not yet clear if there have been changes in suicide mortality rates in Colombia before and during the pandemic.

ObjectiveTo describe and analyze the changes in the temporal trends of suicide mortality rates in Colombia between 2008 and 2020.

MethodsBased on national records, suicide mortality rates observed in Colombia during the COVID-19 pandemic were calculated and compared with those reported in previous years (2008–2019). Mortality rates were analyzed by age, sex, educational level, type of affiliation to health system, region, and etiology of death by suicide. Using the joint point regression software 3.4.4, changes in time trends in suicide mortality rates were estimated for each mentioned variable. Annual percentage changes (APC) were estimated, and their statistical significance was calculated.

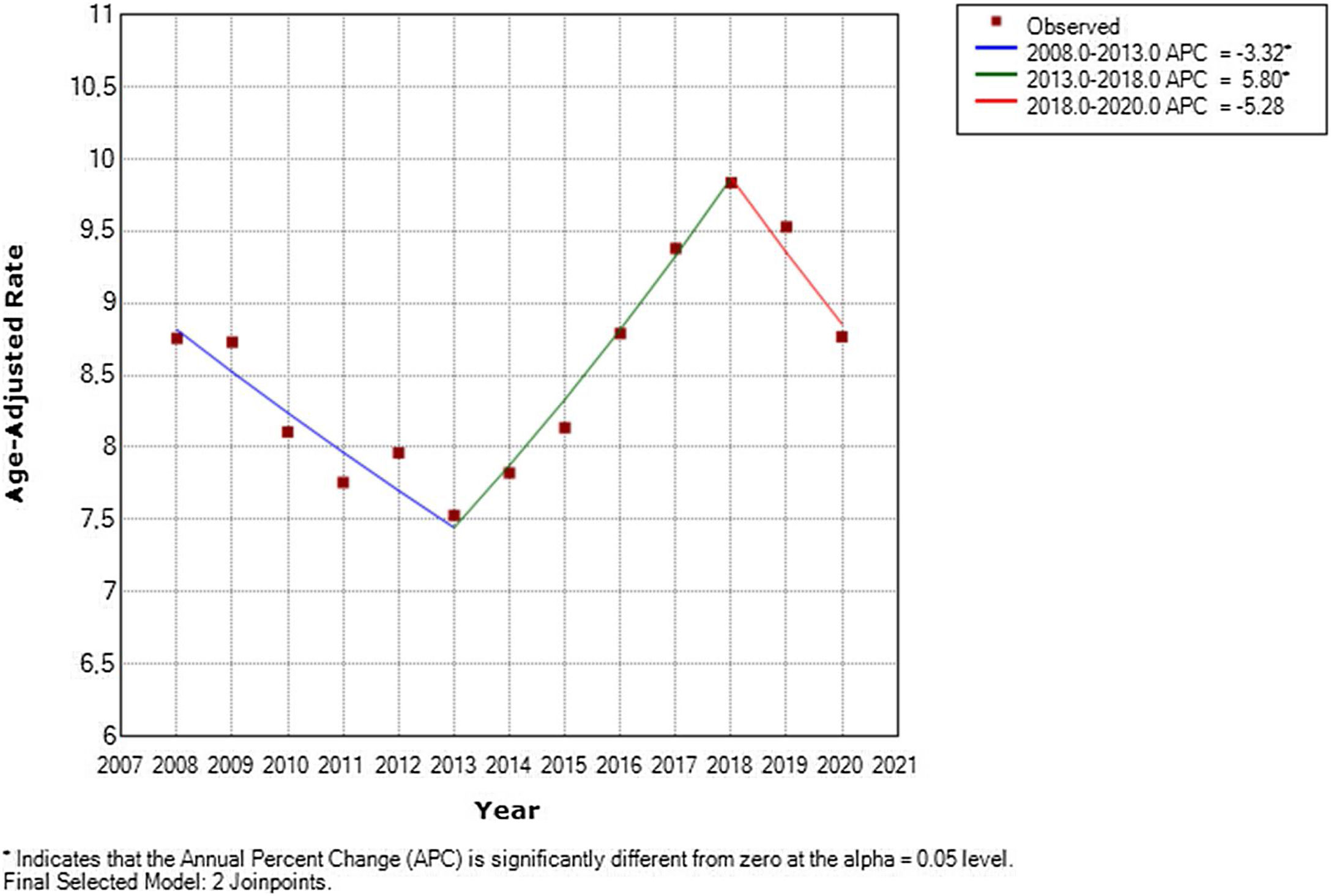

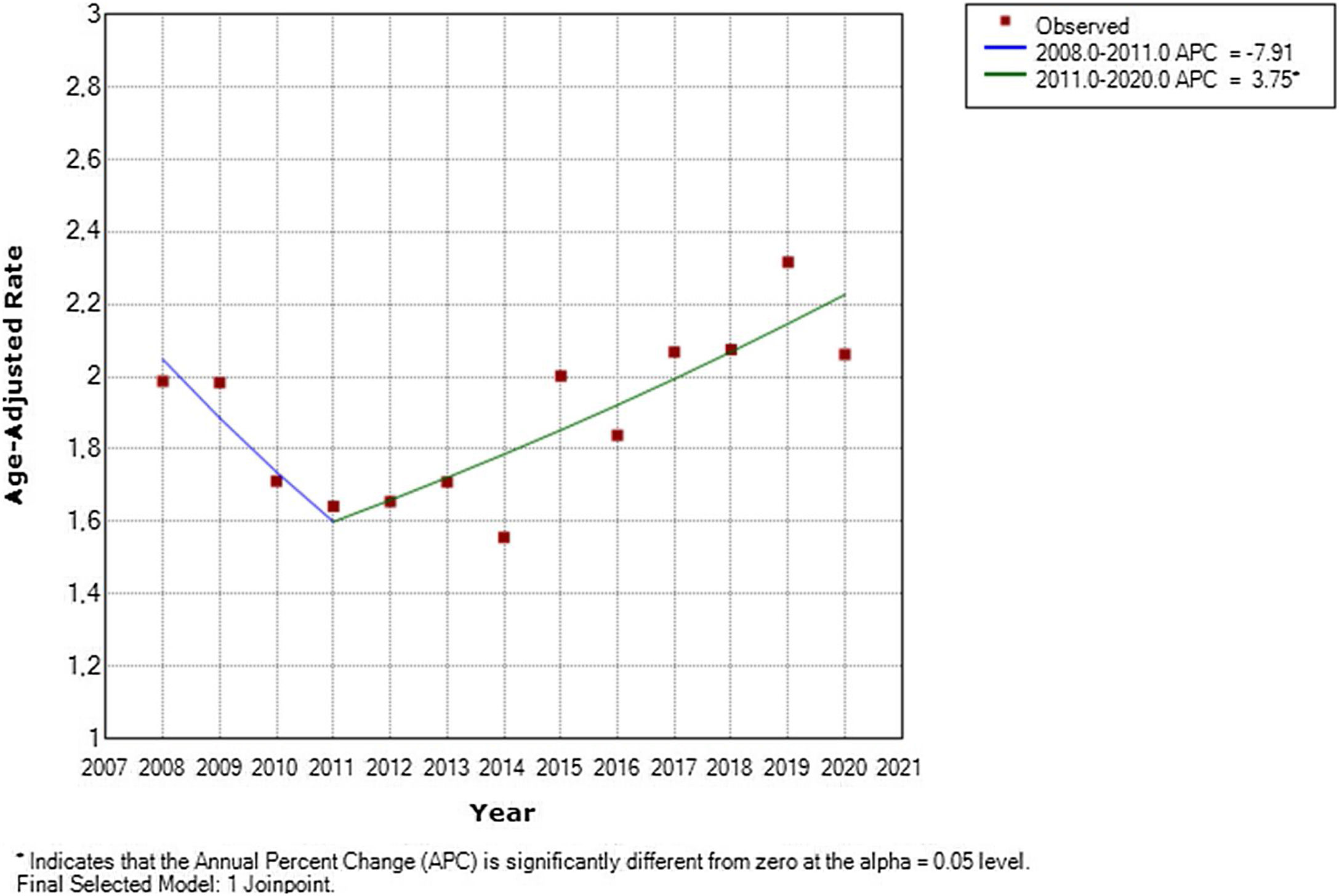

ResultsThe crude suicide mortality rate in Colombia in 2020 (5.4 per 100000 inhabitants) decreased compared to those reported in the previous 3 years. Estimates of changes in time trends in suicide mortality rates between 2008 and 2020 showed a decrease in men of −5.28 (APC) (p<0.05) between 2018 and 2020, and an increase in women of 3.75 (APC) (p<0.05) between 2011 and 2020. Regarding age (by five-year periods), an increase of 3.87 (APC) (p<0.05) was determined in people between 15 and 19 years old between 2012 and 2020. According to health system affiliation regimen, decreases were estimated between 2016 and 2020 (−58.45 CPA; p<0.05) for people affiliated to especial and exceptional health regimes; and between 2015 and 2020 (−53.49 CPA; p<0.05) for the uninsured.

ConclusionsThe crude suicide mortality rate during the COVID-19 pandemic in Colombia decreased compared to what was reported in the previous years. Although significant changes were found in the temporal trends of suicide mortality rates in different periods for all variables, no significant increases were identified between 2019 and 2020.

La pandemia por coronavirus (COVID-19) se declaró en marzo de 2020. Esta enfermedad afecta el sistema respiratorio, y mostró altas tasas de morbimortalidad durante los años 2020 y 2021. También se ha descrito compromiso neurológico e incremento en las tasas de depresión, ansiedad, insomnio y abuso de sustancias. Las políticas de salud pública para prevenir la infección por COVID-19, la disminución del control y del seguimiento de patologías mentales, así como el impacto social y económico, pueden haber contribuido al incremento en ideación suicida y suicidios consumados. Aún no está claro si se han presentado cambios en las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio en Colombia antes y durante la pandemia.

ObjetivoDescribir y analizar los cambios en las tendencias temporales de las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio en Colombia entre 2008 y 2020.

MétodosCon base en registros nacionales, se calcularon y compararon las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio observadas en Colombia durante la pandemia por COVID-19 con las reportadas en años anteriores (2008-2019). Las tasas de mortalidad se analizaron con respecto a edad, sexo, nivel educativo, tipo de afiliación al sistema de salud, región y método empleado en la muerte por suicidio. Mediante el software del programa de regresión joint point 3.4.4 se estimaron los cambios en las tendencias temporales de las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio para cada variable. Se estimaron los cambios porcentuales anuales (CPA) y se calculó su significancia estadística.

ResultadosLa tasa cruda de mortalidad por suicidio en Colombia en el año 2020 (5,4×100.000 habitantes) disminuyó con respecto a las tasas reportadas en los 3 años anteriores. Las estimaciones de los cambios en las tendencias temporales de las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio entre 2008 y 2020 mostraron una disminución en los hombres de −5,28 (CPA) (p<0,05) entre 2018 y 2020, y un aumento en las mujeres de 3,75 (CPA) (p<0,05) entre 2011 y 2020. Con respecto a la edad por quinquenios, se determinó un aumento de 3,87 (CPA) (p<0,05) en personas entre 15 y 19 años entre 2012 y 2020. También se estimaron disminuciones en las tendencias temporales por suicidios entre 2016 y 2020 de −58,45 (CPA) (p<0,05) para las personas afiliadas a regímenes especiales y excepcionales de salud, y de −53,49 (CPA) (p<0,05) entre 2015 y 2020 para los no asegurados.

ConclusionesLa tasa cruda de mortalidad por suicidio durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Colombia disminuyó con respecto a lo reportado en años anteriores. Aunque se encontraron cambios significativos en las tendencias temporales de las tasas de mortalidad por suicidio en diferentes períodos para todas las variables, no se identificaron incrementos significativos entre 2019 y 2020.

Suicidal behaviors are complex phenomena that threaten life and can negatively affect people's health and the emotional state of families and the community. They comprise various degrees and types such as suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and actual suicide occurrence.1 Being a global public health concern, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a worldwide mental health goal to reduce by 10% the mortality rate from suicide by 2020.2

During the last century, there have been viral infectious outbreaks that have increased the overall mortality rates and the incidence of mental illness.3 In March 2020, the WHO declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic; this infection mainly affects the respiratory system, and displayed high mortality rates.4 Furthermore, extrapulmonary manifestations of the COVID-19 infection have been described, including neurological conditions caused by the overexpression of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in the brain endothelium (which allows viral entry), and the invasion of peripheral nerves that can cause disorientation, confusion, delirium, hallucinations, and suicidal behaviors.5–9

Clinical symptoms such as fear and anxiety associated with COVID-19 (including the possibility of dying from it), led to prolonged states of anxiety that increased the risk of major psychiatric disorders.10 In addition, public policies implemented by governments such as social isolation, the use of face masks, frequent hand washing, and cleaning of contact surfaces,11–13 increased rates of distress manifested as dysphoria, anxiety, insomnia, traumatic stress disorders, and suicidal ideation.14 The economic crisis, temporary and overall unemployment due to quarantines, decrease in wages, and rising debts could be associated to increased anxiety and depression, that in turn would increase suicide ideation and suicidal behaviors.15–17

Suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, impaired family functioning, history of mental health disease, alcohol abuse, COVID-19-related stress symptoms, marital status, financial pressure, unemployment, among others.18–23 However, the existing evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide attempts is scant. Thus, there is an evidence gap – with important public health implications – regarding the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and no estimates on how rates might change when pandemic-related social restrictions are reduced or removed.24

Worldwide, cases of people who died by suicide have linked to fear of COVID-19, of transmitting the virus to others, of isolation, anxiety about COVID-19, and lack of knowledge. Other triggers that have been identified for pandemic-related suicides include xenophobia, stigma, social boycott related to the virus, financial insecurities, and uncertainty about the future.25,26 Few observational studies have analyzed the effect of the pandemic on suicidal behavior. Existing studies are restricted to the early phases of the pandemic, and thus may not capture the impact of massive and prolonged social trauma.24

In Colombia, Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) indicated that in the first quarter of 2021, 709 cases of suicide were registered – an increase of 161 cases compared to the same period in 2020. Likewise, an increase was reported between 2019 and 2020.27 However, there are few studies that compare the suicide situation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the objective of this research was to describe and analyze the changes in temporal trends of suicide mortality rates between 2008 and 2020 in Colombia.

MethodsThe main data source for this study was the DANE registry of vital statistics of births and deaths (deaths due to intentional self-inflicted injuries by year, sex, department of occurrence, and educational level 2008–2020). To obtain mortality rates by type of affiliation to health system (2008–2020), we used the national annual series of affiliation in the period 1995–2020 published by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, whose sources correspond to the subsidized regime affiliation history, compensated affiliation history, insurance bulletin (2016), and the Single Affiliate Database – Solidarity and Guarantee Fund. Records of active affiliates to the contributory, subsidized, and exception health regime by department prepared by the Administrator of the Resources of the General System of Social Security in Health in Colombia (2008–2020), were also included.

Mortality rates by educational level were retrieved from the statistical information on the number of students enrolled in basic secondary and middle school by grades and sector (2008–2019), the reports published by the Integrated System of Enrollment of the Ministry of Education of Colombia, and the data in the Technical Document ISP/DT No. 033-19 of the Institute of Public Health of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana on the demand for higher education in Colombia, projections 2019–2040 published in December 2019. Finally, to analyze mortality rates against each variable included in the study, the 2005–2017 and 2018–2050 departmental population projections reported by DANE were used.

All the information retrieved was sorted in a single database under the following variables: sex, age, type of affiliation to health system (contributory, subsidized, especial/exception, uninsured, or without information), educational level (preschool, primary school, secondary school, technical education, high school, technological education, postgraduate, university), region (by department), and suicide method. Using the R Studio statistical program, we performed the 2008–2020 descriptive statistical analysis for each variable, and calculated the disaggregated crude annual mortality rate per variable, the age-adjusted mortality rate (according to the five-year standard WHO reference), and the crude average suicide mortality rates by region between 2008 and 2020.

The joint point regression program 3.4.4 software developed by the National Cancer Institute of the United States was used to estimate changes in temporal trends of suicide mortality rates in Colombia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic by age (five-year groups), sex, region, educational level, and type of affiliation to the health system. Annual percentage changes (APC) were estimated at a significance level of 0.05. Finally, using the statistical program QGIS, a choropleth map of Colombia was made, illustrating the crude average mortality rates due to suicide by departments in Colombia between 2008 and 2020.

Ethical considerationsIn accordance with the scientific and technical standards of resolution No. 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, this study is considered a risk-free investigation. Data was stored securely and in compliance with the principles stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding data access, management, confidentiality, anonymity, integrity, and documentation. Statistical analysis was impartial and responsible.

ResultsThe crude mortality rate due to suicide in Colombia in 2020 was 5.4 per 100000 inhabitants. This was lower than that reported in the previous three years, where rates of 5.7 (2017), 5.9 (2018), and 5.9 per 100000 inhabitants (2019) were reported. The average mortality rate estimated due to suicide in Colombia (2008–2020) ranged between 1.9 and 33.6 per 100000 inhabitants (Fig. 1).

Between 2008 and 2020, the region with the highest average suicide mortality rate was Vaupés (33.6 per 100000 inhabitants), followed by Amazonas and Arauca (Fig. 1). The regions with the lowest rates were Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina, and Chocó. It was estimated that 81% of the cases were males. The age groups in which more cases of suicide were registered were the groups from 20 to 24, 15 to 19, and 25 to 29 years old.

The educational levels with the highest number of events were primary and secondary school. The most common suicide methods were intentionally self-inflicted injury by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (55.12%), followed by intentional self-inflicted poisoning, and intentional self-inflicted injury by gunshot.

Estimates of change in temporal trends of suicide mortality rates in Colombia between 2008 and 2020 by sex showed two statistically significant decreases of −3.32 annual percentage change (APC) (2008–2013) and −5.28 APC (2018 and 2020) for men (Fig. 2). In women, between 2011 and 2020, there was a statistically significant increase in the temporal trend of 3.75 APC (Fig. 3).

When estimating changes in temporal trends based on age by five-year groups, a statistically significant APC increase was determined between 2012 and 2020 in people in the 15–19 age group. A decrease in the trend between 2008 and 2015 in people in the 20–24 age group was also found. In the 35–39 age group, there was a statistically significant decrease in the trend between 2008 and 2013, and there was an increase in the trend between 2013 and 2018. In the 40–44 age group, a positive and statistically significant trend was found (without a change in the temporal trend throughout the period of time analyzed). Between 2012 and 2018, there was a statistically significant positive change in the 45–49 age group. There were statistically significant increasing trends in suicide mortality rates between 2008 and 2020 in the 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, and 65–69 age groups. Finally, between 2011 and 2020 there was a statistically significant increase in the trend in the 75–79 age group (Table 1).

Suicide mortality temporal trends by age (five-year groups) in Colombia (2008–2020). Joint point analysis.

| Period | APC | Statistical significance(p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5–9 | 2008–2011 | 51.69 | NS |

| 2011–2015 | −35.71 | NS | |

| 2015–2020 | 45.27 | NS | |

| 10–14 | 2008–2011 | −3.56 | NS |

| 2011–2015 | 19.86 | NS | |

| 2015–2020 | 4.56 | NS | |

| 15–19 | 2008–2012 | −5.13 | NS |

| 2012–2020 | 3.87 | <0.05 | |

| 20–24 | 2008–2015 | −2.75 | <0.05 |

| 2015–2018 | 7.98 | NS | |

| 2018–2020 | −3.65 | NS | |

| 25–29 | 2008–2020 | −0.02 | NS |

| 30–34 | 2008–2014 | −3.78 | NS |

| 2014–2018 | 7.63 | NS | |

| 2018–2020 | −10.8 | NS | |

| 35–39 | 2008–2013 | −5.17 | <0.05 |

| 2013–2018 | 8.06 | <0.05 | |

| 2018–2020 | −9.62 | NS | |

| 40–44 | 2008–2020 | 1.93 | <0.05 |

| 45–49 | 2008–2012 | −4.35 | NS |

| 2012–2018 | 5.94 | <0.05 | |

| 2018–2020 | −10.12 | NS | |

| 50–54 | 2008–2020 | 2.34 | <0.05 |

| 55–59 | 2008–2020 | 2.38 | <0.05 |

| 60–64 | 2008–2020 | 2.39 | <0.05 |

| 65–69 | 2008–2020 | 3.77 | <0.05 |

| 70–74 | 2008–2020 | −0.1 | NS |

| 75–79 | 2008–2011 | −17.23 | NS |

| 2011–2020 | 5.93 | <0.05 | |

| >80 | 2008–2020 | 1.82 | NS |

APC: annual percentage change; NS: no statistical significance.

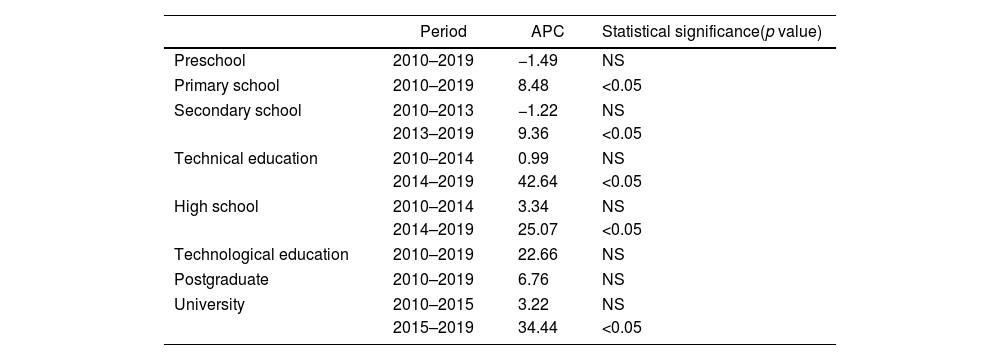

Regarding the educational level, a statistically significant APC increase in the temporal trend between 2013 and 2019 was estimated in people who were enrolled in basic secondary school. An increase in the trend of the suicide rate in people enrolled at the technical level was also estimated for the period 2014–2019, with a reported APC of 42.64. In this same period, people in the high school group had a statistically significant increase in the suicide trend. Finally, between 2015 and 2019, there was a statistically significant APC increase in people enrolled at the university level (Table 2).

Suicide mortality temporal trends by educational level in Colombia (2008–2020). Joint point analysis.

| Period | APC | Statistical significance(p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool | 2010–2019 | −1.49 | NS |

| Primary school | 2010–2019 | 8.48 | <0.05 |

| Secondary school | 2010–2013 | −1.22 | NS |

| 2013–2019 | 9.36 | <0.05 | |

| Technical education | 2010–2014 | 0.99 | NS |

| 2014–2019 | 42.64 | <0.05 | |

| High school | 2010–2014 | 3.34 | NS |

| 2014–2019 | 25.07 | <0.05 | |

| Technological education | 2010–2019 | 22.66 | NS |

| Postgraduate | 2010–2019 | 6.76 | NS |

| University | 2010–2015 | 3.22 | NS |

| 2015–2019 | 34.44 | <0.05 | |

APC: annual percentage change; NS: no statistical significance.

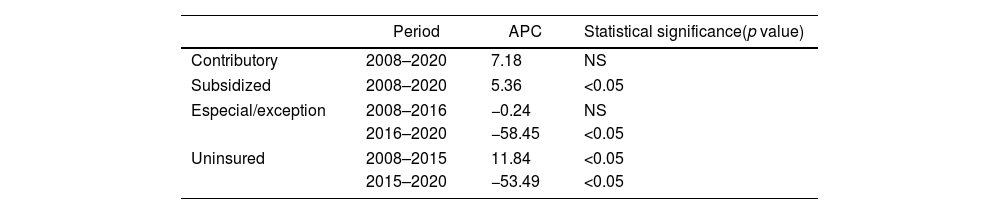

According to the affiliation type to the health system, statistically significant decreases in suicide trends were estimated between 2016 and 2020 for those affiliated to especial and exception health regimens (−58.45 APC), and between 2015 and 2020 for those uninsured (−53.49 APC) (Table 3).

Suicide mortality temporal trends by type of affiliation to the health system in Colombia (2008–2020). Joint point analysis.

| Period | APC | Statistical significance(p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contributory | 2008–2020 | 7.18 | NS |

| Subsidized | 2008–2020 | 5.36 | <0.05 |

| Especial/exception | 2008–2016 | −0.24 | NS |

| 2016–2020 | −58.45 | <0.05 | |

| Uninsured | 2008–2015 | 11.84 | <0.05 |

| 2015–2020 | −53.49 | <0.05 | |

APC: annual percentage change; NS: no statistical significance.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Colombia that evaluates changes in temporal trends of suicide mortality between 2008 and 2020. Social, psychological, clinical, and economic risk factors are associated with anxiety and depression of communities.28 Suicides and suicidal behaviors are major public health concerns worldwide,28 and the COVID-19 pandemic is being associated with an increase in their morbidity and mortality.29 Despite the above, pathways which correlate COVID-19 and suicide remain unclear.29 In our study, sex, age, educational level, and health insurance affiliation were collected in different periods between 2008 and 2020. However, we did not find significant differences between the suicide rates between 2019 and 2020 (pandemic start). This could be attributed, among other reasons, to the scarce in data collected which may have led to underestimate the effect of the pandemic, also impacting our results due to residual confounding.30 Factors related to stigma, economic status, social isolation, healthcare access, and social and geographical conditions should be further studied to estimate the effect of the pandemic in countries like Colombia.30

It has been published that at early stages of the pandemic the prevalence of suicides remained stable or fell, especially in vulnerable populations such as women, ethnic minorities, younger age groups, and low and middle income countries.8,31,32 This could be explained by the success of health policies, lockdowns, vaccine development and vaccination access, suicide prevention strategies, new ways to interact with each other, reduction of conflicts, and a survival collective feeling.8,31 Our results contribute to expanding the evidence on changes in suicide trends over time by comparing the period before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic with the first year of the pandemic in Colombia. These results are consistent with those of other recently published studies,31,33–35 which also indicate that there was no increase in the annual rate or a growing trend in suicide mortality in times of pandemic. This would suggest that the start of the pandemic did not significantly affect overall suicide trends, meaning that the interaction between COVID-19 and the time of monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the pandemic is not significant, but changes could occur in the medium and long term. Further investigation, specific analyses, and predictive models are needed to estimate the effect of the pandemic in latter stages of the disease.29,36

On the other hand, most of the studies that have evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on suicide rates have analyzed general rates – not by age strata or subgroups like ours. In the study published by Chen et al.,34 through an interrupted time series analysis, trends stratified by age (<25, 25–44, 45–64, ≥65) were modeled in the rates of suicide before (January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2019) and after (January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020) in Taiwan. They found a slight decrease in the overall suicide rates after the outbreak; and in the analysis by age, suicide rates increased in the youngest (<25 years) and decreased in the middle-aged group (25–64 years).34 Similarly, our estimation showed a suicide rate increase in people between 15 and 19 years old. The increase in the suicide rate before and after the pandemic in young population reflects the global concern regarding deterioration of mental health in this group, which may be caused by internet addiction, substance abuse, and the lack of family support.37

Joint point regression analyses have been used to estimate changes in mortality rates from cancer and traffic accidents in different time series. One of its strengths is being able to identify the moment in which the rate trend changes. The use of this method has increased in recent years (especially in ecological studies) to understand population dynamics and epidemiological changes. This statistical analysis model was identified in the study carried out by Pérez et al.,35 in which suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and tendencies were examined in 2020 in relation to 2019, as an approach to the impact of the pandemic on the suicidal behavior and death in the general population of Catalonia, Spain. Results showed a substantial decrease in rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors with a monthly percentage change (MPC) of −22.1 (95% CI: −41.1 to 2.9) from January to April 2020, followed by a similar increase from April to July 2020 (MPC=24.7; 95% CI: −5.9 to 65.2).35 Likewise, the number of suicide-related events registered in the Catalan Suicide Risk Code (CSRC) was 5% lower than it was in 2019; similar to that presented in our study (6.90%). Suicidal behavior and mortality should continue to be monitored to better understand the medium and long-term impact of COVID-19 on suicide trends.35

Finally, another strength of our study (unlike other studies with similar objectives) is the evaluation of suicide trends over a broader period of time and not just the comparison between 2020 and the year before the pandemic. Only one study has compared the risk of suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic against data from other years (2010–2019) using an interrupted time series analysis.38 The period of time evaluated in our study is longer (12 years). This work provides a starting point for future research that can establish the causal effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of mortality from suicide in Colombia.

ConclusionsThis is the first epidemiological study to evaluate temporal trend changes in suicide mortality rates in Colombia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The crude suicide mortality rate in 2020 decreased compared to the rates reported in the previous 3 years. Although changes were found in the temporal trends of suicide mortality rates in different periods for all variables, no significant increases were identified between 2019 and 2020. Multiple clinical, epidemiological, and socioeconomic risk factors have been associated with COVID-19 infection; therefore, further investigation is required to determine the effect of the pandemic on suicide mortality in Colombia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have declared that no conflicting interests exist.

Article based on an academic thesis to opt for the title of M.Sc. in Health Economics at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, 2022.