Self-reported psychological variables related to pain have been posited as the major contributors to the quality of life of fibromyalgia (FM) women and should be considered when implementing therapeutic strategies among this population. The aim of this study was to explore the effect of low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) on psychological constructs related to pain (i.e., pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain inflexibility, mental defeat) and quality of life in women with FM.

MethodsThis was a randomized controlled trial. Thirty-three women with FM were randomly allocated to a low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy group (HBOTG) (n=17), who received an 8-week intervention (5 sessions per week), and a control group (CG) (n=16). All women were assessed at baseline (T0) and upon completion of the study (T1) for self-perceived pain intensity, pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain inflexibility, mental defeat and quality of life.

ResultsAt T1, the HBOTG improved across all variables related to pain (i.e. self-perceived pain intensity, pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain flexibility, mental defeat) (p<0.05) and quality of life (p<0.05). In contrast, the CG showed no improvements in any variable. Furthermore, significant differences between the groups were found in quality of life (p<0.05) after the intervention.

ConclusionsHBOT is effective at improving the psychological constructs related to pain (i.e. pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain flexibility, mental defeat) and quality of life among women with FM.

Clinical Trial Link Clinical Trials gov identifier (NCT03801109).

Las variables psicológicas autoinformadas relacionadas con el dolor han sido postuladas como las principales contribuyentes a la calidad de vida de las mujeres con fibromialgia (FM) y deben ser consideradas al momento de implementar estrategias terapéuticas en esta población. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar el efecto de la oxigenoterapia hiperbárica de baja presión (HBOT) sobre los constructos psicológicos relacionados con el dolor (catastrofismo del dolor, aceptación del dolor, inflexibilidad del dolor, derrota mental) y la calidad de vida en las mujeres con FM.

MétodosSe realizó un ensayo clínico controlado aleatorizado. Treinta y tres mujeres con FM fueron asignadas aleatoriamente a un grupo de oxigenoterapia hiperbárica de baja presión (HBOTG) (n=17), que recibió una intervención de 8 semanas (5 sesiones por semana) y un grupo control (GC) (n=16). Las mujeres fueron evaluadas al inicio (T0) y al finalizar el estudio (T1) para determinar la intensidad del dolor autopercibido, el catastrofismo del dolor, la aceptación del dolor, la inflexibilidad del dolor, la derrota mental y la calidad de vida.

ResultadosEn T1, el HBOTG mejoró en todas las variables relacionadas con el dolor (intensidad del dolor autopercibido, catastrofismo del dolor, aceptación del dolor, flexibilidad del dolor, derrota mental) (p<0,05) y calidad de vida (p<0,05). Por el contrario, el GC no mostró mejorías en ninguna variable. Además, se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los grupos en la calidad de vida (p<0,05) después de la intervención.

ConclusionesLa HBOT es eficaz para mejorar los constructos psicológicos relacionados con el dolor (es decir, catastrofismo del dolor, aceptación del dolor, flexibilidad del dolor, derrota mental) y la calidad de vida en las mujeres con FM.

Clinical Trial Link Clinical Trials gov identifier (NCT03801109).

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common chronic syndrome mainly characterized by chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain and other disabling symptoms at both the physical and psychological levels.1 These symptoms influence daily life considerably, affecting the individual's work capacity, as well as both familiar and social commitments, and ultimately quality of life.2

In recent years, the therapeutic target for chronic pain in general, and FM in particular, has changed from designing a merely symptom-focused treatment to considering all components comprising the experience of chronic pain. In this regard, the biopsychosocial model posits that the way that an individual copes with pain plays a crucial role in the pain experience, supporting the idea that the individual's ability to manage pain is a key factor to consider when evaluating the condition or implementing therapeutic strategies in FM patients.3 Consistent with this idea, psychological constructs like pain catastrophizing, pain acceptance, psychological flexibility, and mental defeat have gained attention in FM research in recent decades.

Pain catastrophism refers to a negative cognitive-affective response to actual or anticipated pain characterized by the tendency to magnify the threat value of pain.4 In the context of chronic pain, a particular type of self-catastrophism, so called mental defeat focused on the negative effects of the pain experience on the person's autonomy and identity, has been studied.5 These constructs have been directly associated with pain interference, sleep disruption, depression, anxiety, functional impairment, and psychosocial disability in people with chronic pain.4

In contrast, pain acceptance describes the willingness to experience painful sensations without attempting to reduce or avoid them by the means of psychological flexibility. Higher pain catastrophizing and lower pain acceptance have been associated with pain severity and worse emotional and physical functioning in people with chronic pain.6 Furthermore, psychological flexibility, as the ability to adapt and reconfigure mental resources, has been proposed as a relevant variable that predicts better treatment outcomes.7

Interestingly, the self-reported variables related to pain, and not pain intensity, have been posited as major contributors to the quality of life reported by FM patients.8 Self-perceived quality of life, in turn, constitutes an important factor to be considered when planning and evaluating treatment strategies among patients coping with a chronic illness.8

However, beyond psychological therapeutic approaches like the cognitive behavioral treatment, little is known about the possibility of improving important variables by other common therapies in people with FM. We previously reported that a low-intense physical exercise program was able to improve pain catastrophism in people with FM.9 However, due to the high levels of fatigue experienced by people with FM, exercise engagement is not always possible and the search for other non-fatiguing therapies is a paramount challenge in the FM therapeutic approach. In this regard, low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) has emerged as an effective strategy to improve fatigue in the general population.10 We reported that HBOT, but not physical exercise, was able to improve perceived pain intensity and fatigue in FM patients.11 However, to the best of our knowledge, the effect of this kind of therapy on the self-reported variables related to pain in people with FM remains to be elucidated.

Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of low pressure HBOT on psychological constructs related to pain (pain intensity, pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain flexibility and mental defeat) in people with FM. Furthermore, we aimed to assess the effect of the proposed intervention on the self-reported quality of life of the patients.

MethodsParticipantsThirty-three women diagnosed with FM according to the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria were recruited from several Fibromyalgia associations from September 2017 to January 2018 to participate in this randomized controlled trial. The inclusion criteria were as follows: aged between 30 and 70 years old; undergoing a pharmacological treatment for more than three months with no improvement; and had the ability to sign the written informed consent form.

The exclusion criteria included: taking epilepsy or drugs that lower the convulsive threshold; pregnant or breastfeeding; a history of intense headaches; tympanic perforations; endocranial and hearing implants; any further pathology affecting the nervous system, either central or peripheral; uncontrolled arterial hypertension; cardiac pacemaker; heart and/or respiratory failure; pneumothorax; psychiatric pathologies, claustrophobia; neoplasia; recent surgical interventions (less than 4 months ago), and previous hyperbaric treatment. Furthermore, patients with drugs or alcohol addiction were excluded.

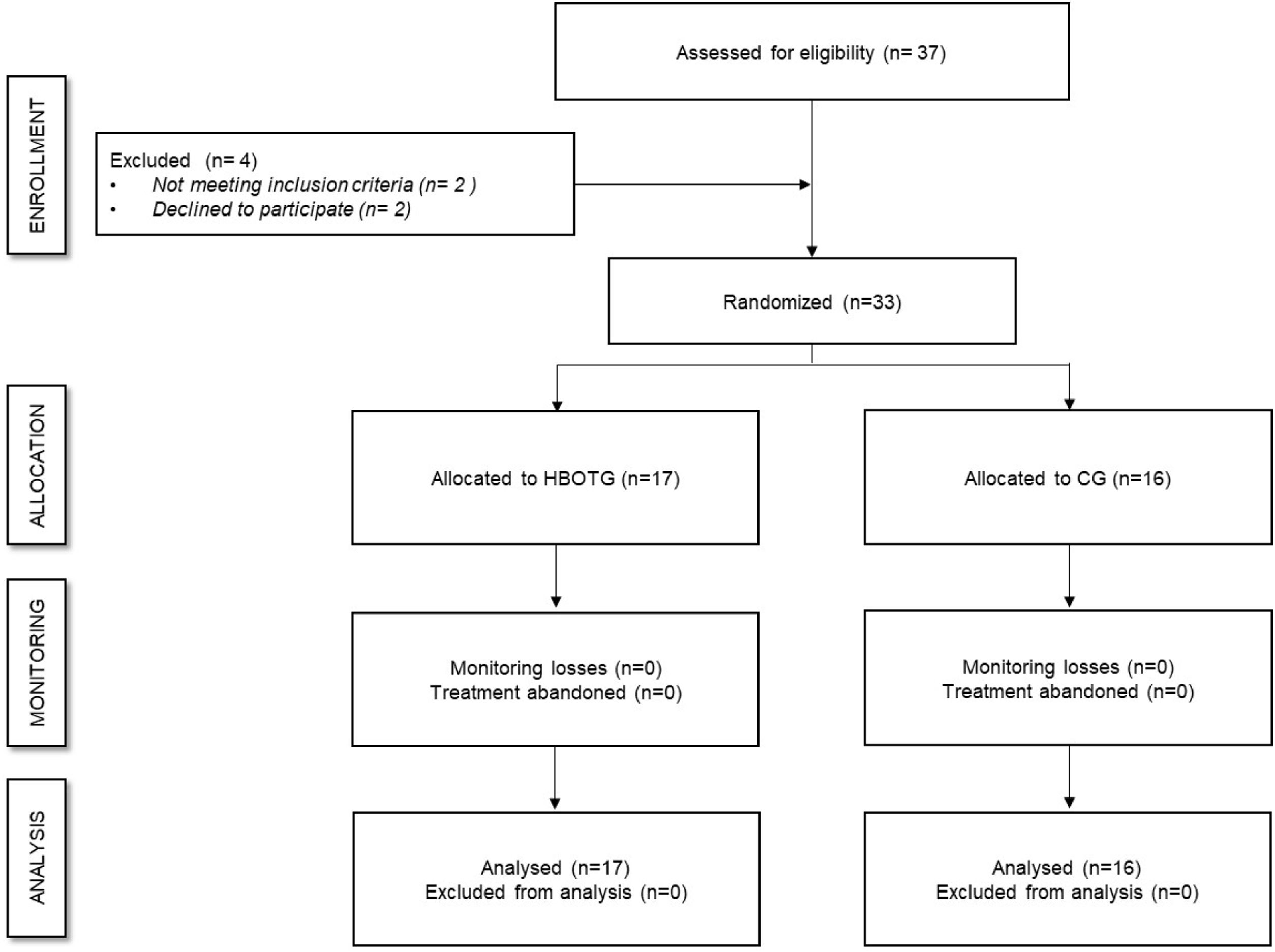

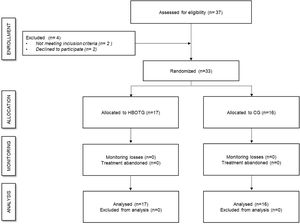

Study designA randomized controlled trial (within a broader project [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03801109]) was carried out. An external blinded assistant was asked to randomly assign participants to one of the following groups, either the hyperbaric oxygen therapy group (HBOTG) (n=17) or the Control group (CG) (n=16). The participants were assessed at baseline (T0) and upon completion of the study (T1). To reduce bias, both the statistician and physical therapist who performed the assessments were unaware of the group allocation.

All participants were asked to provide written informed consent to enter the study which was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat de València (H1548771544856).

Sample sizeSample size was calculated based on the inclusion of two study groups measured twice and with reference to a previous study in which pain catastrophizing was measured. Accordingly, an effect size of d=0.72 was expected. Furthermore, a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 20% were set. This calculation rendered 14 volunteers per group. However, in order to prevent loss of power derived from potential dropouts, 33 women were finally included. G-Power® version 3.1 was used for sample size estimation (Institute for Experimental Psychology, University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Intervention proceduresThe hyperbaric oxygen treatment was applied by an experienced physiotherapist. The participants were not receiving any other pain treatment intervention or rehabilitation program. During each session, any possible pain or discomfort experienced by the patient was recorded, such as earache.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapyThe participants in this group underwent a hyperbaric oxygen treatment as previously described.11 Briefly, the participants received a total of 40 low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen treatment sessions, each lasting 90min, with five sessions per week. Pressurized oxygen (1.45 ATA) at 100% concentration was applied individually through a face mask while the participants were inside the hyperbaric chamber (Revitalair® 430 (Biobarica, Buenos Aires, Argentina)). Pain levels were recorded every day before and after each session according to a visual analog scale.

Control groupThe participants assigned to this group did not receive any therapy during the 8-week intervention period.

AssessmentsAll assessments were conducted twice, once before the intervention and the other after the intervention (in the following week). In order to guarantee the maximum homogeneity between groups, all assessments were carried out on the same day and on the same timeframe (i.e. morning). All participants were instructed not to eat or drink anything stimulant the morning of the experiment (i.e. caffeine). Furthermore, they were encouraged to take a break whenever they feel any sign of fatigue.

Pain intensityPain intensity was assessed using a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS), whereby patients rated their level of pain intensity (0=“no pain” to 10=“worst pain imaginable”). It is considered to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing chronic pain.12

Pain catastrophizing (PCS)The validated Spanish version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) for patients with FM was used to determine pain catastrophizing.13 This is a 13-item-scale evaluating 3 dimensions of pain: Rumination, Magnification, and Helplessness. Each item is scored on a 0 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“All the time”) range. The total score (sum of individual scores) ranges from 0 to 52, whereby higher scores indicate greater pain catastrophizing. The test–retest reliability of the scale is excellent (ICC=0.94).13

Pain acceptance (CPAQ)Pain acceptance was assessed using the 15-item Spanish validated version of the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire for people with FM (CPAQ-FM).14 The items on the CPAQ-FM are rated on a 7-point scale from 0 (never true) to 6 (always true). Higher scores indicate higher levels of acceptance. This tool has shown good test–retest reliability (ICC=0.83) and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's α: 0.83).14

Psychological flexibility (PIPS)Psychological flexibility was assessed using the Spanish validated version of the Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale (PIPS). The questionnaire consists of 12 items related to chronic pain, psychological inflexibility, suffering, and disability. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true), being the total score the sum of the 12 responses. The lower the score, the higher the psychological flexibility. This test has shown a high internal consistency (Cronbach's α: 0.90).15

Mental defeat (PSPS)Mental defeat was evaluated using the Spanish validated version of the Pain Self-Perception Scale (PSPS), a questionnaire used to assess mental defeat in individuals with chronic pain. It consists of 24 statements related to the individual's “recent episode of intense pain”. The statements are rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (Not at all/Never) to 4 (Very strongly). The total score (0–96) results from the sum of the individual items with higher scores representing a greater level of mental defeat. It has been shown to have a high internal consistency (Cronbach's α: 0.90) and good test–retest reliability (ICC=0.97).16

Quality of life (SF-12)Physical, mental, and overall QoL was evaluated using the Spanish version of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), a shortened validated version of its predecessor questionnaire, the SF-36,17 since these two versions have been widely used to evaluate quality of life and have shown good correlation with comparable domains in the FIQR. The SF-12 evaluates the same characteristics of health status as the SF-36 does, specifically physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, and general health perceptions. There was also a mental component that evaluates vitality, social role functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. It has been demonstrated that the three FIQR domain scores predict the 8 SF-36 subscale scores (3), hence, all three questionnaires (SF 12, SF-36 and FIQR) can be used indistinctly, with comparable results. The SF-12 score ranges from 0 to 100, with scores below or above 50 indicating worse or better health status, respectively, than the mean of the reference.17

StatisticsThe data analysis was performed using the SPSS v26 (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For the inferential analysis, a split-plot multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with the between-subject factor “treatment group” having two categories (HBOTG and CG) and the within-subject factor “time assessments” having two categories (T0 and T1). Post hoc analysis was performed using Bonferroni tests. The Shapiro–Wilk t-test and Levene's test were used to analyze data normality and homoscedasticity. The normality assumptions were met in all cases, except for the variables general health, bodily pain, vitality and social functioning. Nevertheless, considering the robustness of the ANOVA test, the analyses were continued. The effect size of the comparisons was computed using Cohen's d where >0.80 means large, 0.50–0.80 medium, and 0.20–0.50 small effect size). Type I error was established as <5% (p<0.05).

ResultsParticipantsIn total, 37 participants were assessed for eligibility and 33 met the inclusion criteria and were randomly divided into two groups (17 in the HBOTG and 16 in the CG) (Fig. 1). The mean (SD) age of the participants was 52.76 (8.18) years old, and the average weight and height were 70.47 (15.17) kg and 161.51 (6.27) cm, respectively. Both groups were well-balanced in terms of physical condition, as assessed by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) (9.39 (2.62) points in the HBOTG and 10.26 (2.68) points in the CG), time since diagnosis (7.38 (5.64) years for the HBOTG and 7.87 (5.86) years for the CG) and previous treatments (all participants underwent a similar pharmacological treatment for more than three months with no improvement, but they should not have received previous HBOT treatment for at least 2 months before participating in the study). There were no significant differences in these variables between the groups at baseline (p>0.05). No incidents were reported during the intervention.

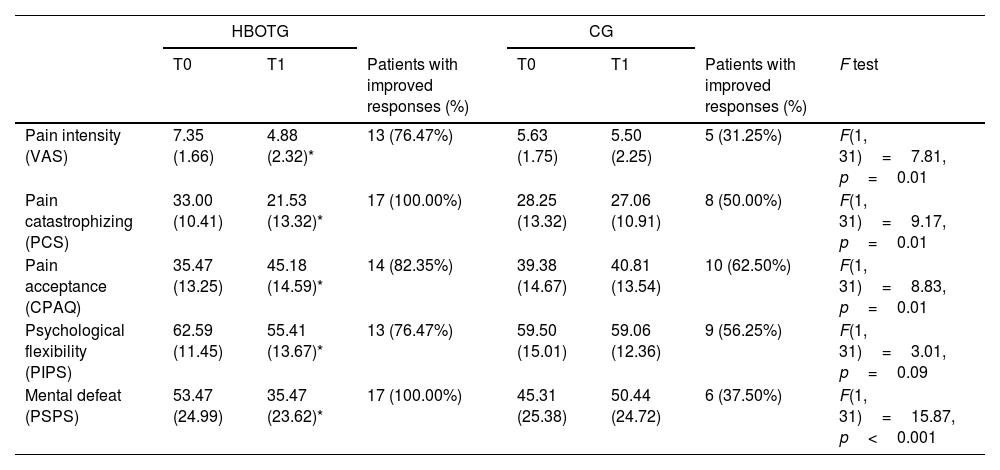

Effects of the interventions on the psychological constructs related to pain (pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, pain acceptance, psychological flexibility, and mental defeat)As shown in Table 1, the HBOTG significantly reduced pain self-perceived intensity (p<0.001; d=1.24), pain catastrophizing (p<0.001; d=0.97), and mental defeat (p<0.001; d=0.74) after the intervention. The participants significantly improved in terms of pain acceptance (p<0.001; d=0.70) and psychological flexibility (p=0.01; d=0.57). However, no significant improvements when compared to baseline were found in the CG (p>0.05).

Effect of the treatments on pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, pain acceptance, psychological flexibility, and mental defeat.

| HBOTG | CG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | Patients with improved responses (%) | T0 | T1 | Patients with improved responses (%) | F test | |

| Pain intensity (VAS) | 7.35 (1.66) | 4.88 (2.32)* | 13 (76.47%) | 5.63 (1.75) | 5.50 (2.25) | 5 (31.25%) | F(1, 31)=7.81, p=0.01 |

| Pain catastrophizing (PCS) | 33.00 (10.41) | 21.53 (13.32)* | 17 (100.00%) | 28.25 (13.32) | 27.06 (10.91) | 8 (50.00%) | F(1, 31)=9.17, p=0.01 |

| Pain acceptance (CPAQ) | 35.47 (13.25) | 45.18 (14.59)* | 14 (82.35%) | 39.38 (14.67) | 40.81 (13.54) | 10 (62.50%) | F(1, 31)=8.83, p=0.01 |

| Psychological flexibility (PIPS) | 62.59 (11.45) | 55.41 (13.67)* | 13 (76.47%) | 59.50 (15.01) | 59.06 (12.36) | 9 (56.25%) | F(1, 31)=3.01, p=0.09 |

| Mental defeat (PSPS) | 53.47 (24.99) | 35.47 (23.62)* | 17 (100.00%) | 45.31 (25.38) | 50.44 (24.72) | 6 (37.50%) | F(1, 31)=15.87, p<0.001 |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation). HBOTG: hyperbaric oxygen therapy group; CG: control group; T0: pre-treatment assessment; T1: post-treatment assessment; VAS: visual analog scale; PCS: Pain Catastrophizing Scale; CPAQ: Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire; PIPS: Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale; PSPS: pain perception scale.

There were no significant differences between groups in any of the studied variables at baseline (p>0.05).

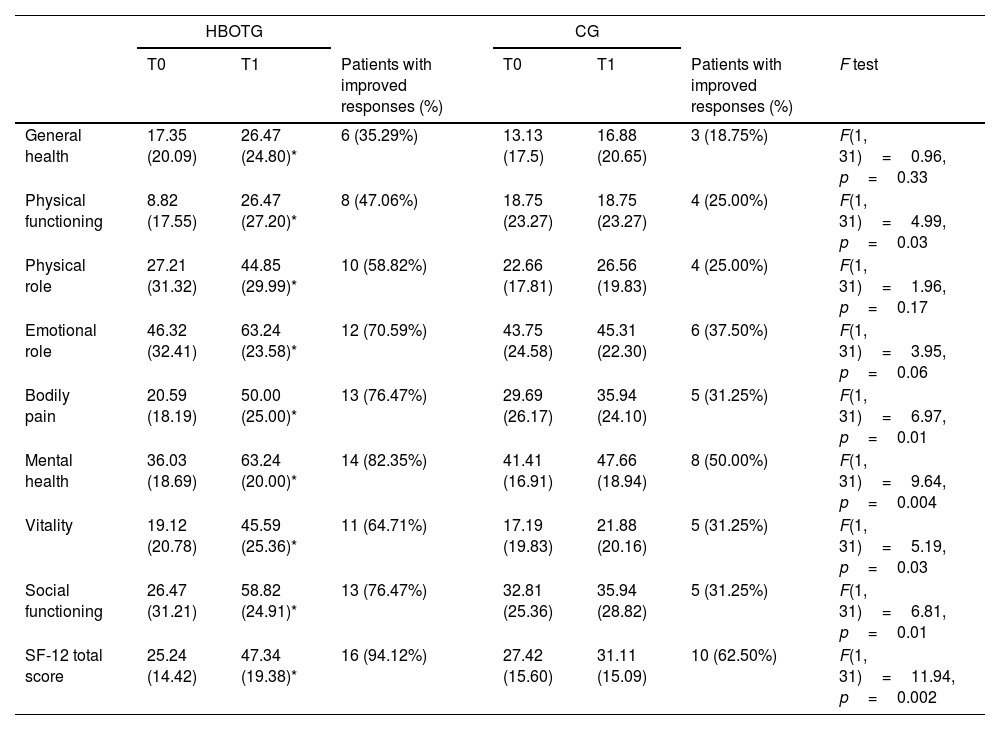

Effects of the interventions on quality of lifeWith regard to quality of life, as measured by the SF-12 (Table 2), significant differences were found for the HBOTG after the intervention. There were improvements in general health (p=0.02; d=0.41), physical functioning (p=0.003; d=0.79), physical role (p=0.02; d=0.58), emotional role (p=0.004; d=0.60), bodily pain (p<0.001; d=1.36), mental health (p<0.001; d=1.41), vitality (p<0.001; d=1.15), social functioning (p<0.001; d=1.15), as well as in the SF-12 total score (p<0.001; d=1.31) after the intervention. The CG did not register any significant improvements in any of the aforementioned items after the intervention (p>0.05).

Effect of the treatments on quality of life.

| HBOTG | CG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | Patients with improved responses (%) | T0 | T1 | Patients with improved responses (%) | F test | |

| General health | 17.35 (20.09) | 26.47 (24.80)* | 6 (35.29%) | 13.13 (17.5) | 16.88 (20.65) | 3 (18.75%) | F(1, 31)=0.96, p=0.33 |

| Physical functioning | 8.82 (17.55) | 26.47 (27.20)* | 8 (47.06%) | 18.75 (23.27) | 18.75 (23.27) | 4 (25.00%) | F(1, 31)=4.99, p=0.03 |

| Physical role | 27.21 (31.32) | 44.85 (29.99)* | 10 (58.82%) | 22.66 (17.81) | 26.56 (19.83) | 4 (25.00%) | F(1, 31)=1.96, p=0.17 |

| Emotional role | 46.32 (32.41) | 63.24 (23.58)* | 12 (70.59%) | 43.75 (24.58) | 45.31 (22.30) | 6 (37.50%) | F(1, 31)=3.95, p=0.06 |

| Bodily pain | 20.59 (18.19) | 50.00 (25.00)* | 13 (76.47%) | 29.69 (26.17) | 35.94 (24.10) | 5 (31.25%) | F(1, 31)=6.97, p=0.01 |

| Mental health | 36.03 (18.69) | 63.24 (20.00)* | 14 (82.35%) | 41.41 (16.91) | 47.66 (18.94) | 8 (50.00%) | F(1, 31)=9.64, p=0.004 |

| Vitality | 19.12 (20.78) | 45.59 (25.36)* | 11 (64.71%) | 17.19 (19.83) | 21.88 (20.16) | 5 (31.25%) | F(1, 31)=5.19, p=0.03 |

| Social functioning | 26.47 (31.21) | 58.82 (24.91)* | 13 (76.47%) | 32.81 (25.36) | 35.94 (28.82) | 5 (31.25%) | F(1, 31)=6.81, p=0.01 |

| SF-12 total score | 25.24 (14.42) | 47.34 (19.38)* | 16 (94.12%) | 27.42 (15.60) | 31.11 (15.09) | 10 (62.50%) | F(1, 31)=11.94, p=0.002 |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation). HBOTG: hyperbaric oxygen therapy group; CG: control group; T0: pre-treatment assessment; T1: post-treatment assessment; SF-12: health-related quality of life short-form.

In this study, we investigated the effect of low pressure HBOT on the psychological constructs related to pain (self-perceived pain intensity, pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain flexibility, mental defeat) and quality of life among women with FM. The results indicate that HBOT significantly improves all studied psychological constructs and quality of life when compared to the control group. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates the effect of a non-psychological intervention, such as HBOT, on psychological constructs that have been proposed as major contributors to quality of life among FM patients.8

HBOT significantly decreased self-perceived pain intensity by 2.47 points and pain catastrophism by 11.47 points after the intervention, both of which exceed the minimum clinically relevant change of 9mm and 3.2–4.5 points, respectively.18 A recent review concluded that HBOT is an effective therapeutic strategy for pain relief19 but there were calls for concern regarding the possible side effects of HBOT, thus advising the use of low-pressure HBOT as used in the current study. This beneficial effect of HBOT on pain perception may be related to the increased oxygen supply to the bloodstream which may have physiological consequences on the whole body (increased metabolic activity, improved mitochondrial function, stem cells proliferation, up-regulation of anti-inflammatory, angiogenic and neurogenic factors)20 and even changes in brain activity. In this regard, it has been suggested that HBOT may improve the abnormal pain processing pathway presumed in individuals with FM, mainly by inducing changes in the brain metabolism/function characteristic. In particular, HBOT may exert such a beneficial effect by decreasing the activity of the posterior hyperactive regions and increasing the activity of the prefrontal hypoactive regions.21 Since these altered brain activity patterns have been shown to play an important role in emotion regulation, HBOT may have modulated the noxious stimulus perception, improving the affective-cognitive attitude toward the pain experience.22

Furthermore, pain catastrophism has been positively correlated to depression where the same altered brain activity has been observed.23 In addition, HBOT stimulates nitric oxide synthesis which helps to alleviate hyperalgesia and the release of endogenous opioids which have been proposed to be the primary HBOT mechanism of analgesia.24

This positive finding on self-perceived pain intensity and pain catastrophism was further reinforced by a significantly increased pain acceptance and flexibility after the HBOT treatment. These two constructs have gained attention in pain research in recent years since they have been proposed as indicators of resilience. Indeed, while pain catastrophism may be considered a vulnerability factor of chronic pain, pain acceptance and flexibility may be considered resilience factors since they promote adaptation to chronic pain.25 Interestingly, higher pain catastrophizing and lower pain acceptance levels have been associated with an impaired physical functioning at both performance-based and self-reported levels.6 We observed that both the physical functioning and physical role components of the SF-12 improved only in the HBOTG and not in the CG. Interestingly, physical deconditioning may not only have a negative impact on the individual's quality of life but also his/her professional performance, which leads to work absenteeism.2

Unfortunately, the results on the aforementioned psychological variables observed in this study cannot be compared with the previous studies since this is the first study to determine the effect of HBOT on such constructs. Other therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy26 pain neuroscience education27 and physical exercise9 have been shown to improve pain catastrophism in individuals with FM. With regard to physical exercise, we previously reported that a physical therapy program (i.e. a low-intensity exercise program) was able to improve pain catastrophism and acceptance in people with FM.9 These results are of great importance since they reveal that a passive intervention such as HBOT yields similar results to other interventions that require an active role of the individual which is not always possible due to the special characteristics of this population.

Another construct related to pain that has gained attention in chronic pain research in recent years is mental defeat, which has been proposed as a type of catastrophism that considers chronic pain to be an attack on the individual's life and sense of identity, even being considered a risk factor for suicidal intent in individuals with chronic pain.28 Our results indicating that HBOT significantly reduces mental defeat are therefore of great importance since mental defeat has been proposed to be a key cognitive marker of the collapse of pain self-management.29

Finally, we report that the group receiving HBOT significantly improved in terms of their self-perceived quality of life, as assessed by the SF-12 scale. This is in agreement with the other studies showing that HBOT effectively improves the quality of life among FM patients.21 A plausible reason for this improvement may be the fact that HBOT restores, in part, the abnormal microstructure and activity of the brain by inducing neural plasticity.30 Improvements in quality of life after HBOT have been correlated with a better brain structure and activity, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging and single-photon emission computed tomography respectively among FM patients.21

The present study has some limitations, the major one being the small sample size. Although the a priori power analysis performed prior to the study indicated that the sample size was sufficient to obtain significant results, further studies could confirm the results reported here in a larger population. Furthermore, since the FM female-to-male incidence ratio is 9:1, only women were included in the study, so the role of gender in these findings may have been overlooked. Finally, it might have been interesting to analyze the biological mechanisms underlying the observed findings.

ConclusionsWithout waiving the limitations mentioned above, low-pressure HBOT is effective at improving the psychological constructs related to pain (self-perceived pain intensity, pain catastrophism, pain acceptance, pain flexibility, mental defeat) and quality of life among women with FM. Therefore, HBOT may be considered a valid therapeutic approach to improving pain management among FM patients.

Ethical considerationsAll women were asked to provide written informed consent to enter the study which was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat de València (H1548771544856).

FundingThis work was supported by Grants from Generalitat Valenciana, Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat (CIAICO/2021/215); and from Universitat de València (INV19-01-13-07).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. The authors declare they do not have any potential conflict of interest with regard to the investigation, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We thank all participants that participated in the study and AVAFI association.