Serious adverse events during hospital care are a worldwide reality and threaten the safety of the hospitalised patient.

ObjectiveTo identify serious adverse events related to healthcare and direct hospital costs in a Teaching Hospital in México.

Materials and methodsA study was conducted in a 250-bed Teaching Hospital in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Data were obtained from the Quality and Patient Safety Department based on 2012 incidents report. Every event was reviewed and analysed by an expert team using the “fish bone” tool. The costs were calculated since the event took place until discharge or death of the patient.

ResultsA total of 34 serious adverse events were identified. The average cost was $117,440.89 Mexican pesos (approx. €7000). The great majority (82.35%) were largely preventable and related to the process of care. Undergraduate medical staff were involved in 58.82%, and 14.7% of patients had suffered adverse events in other hospitals.

ConclusionsSerious adverse events in a Teaching Hospital setting need to be analysed to learn and deploy interventions to prevent and improve patient safety. The direct costs of these events are similar to those reported in developed countries.

Los eventos adversos graves durante la atención hospitalaria son una realidad a nivel mundial y ponen en riesgo la seguridad del paciente hospitalizado.

ObjetivoIdentificar los eventos adversos graves relacionados con el proceso de atención y los costos directos en un hospital de enseñanza en México.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio en un hospital de enseñanza de 250 camas censables en San Luis Potosí, México. Los datos fueron proporcionados por el departamento de Calidad y Seguridad del Paciente, con base en los incidentes reportados en 2012. Cada evento fue revisado y analizado por un grupo de expertos, utilizando la herramienta «espina de pescado». Los costos hospitalarios directos fueron calculados desde que el evento adverso ocurrió hasta el alta o la muerte del paciente.

ResultadosSe identificaron 34 eventos adversos graves. El costo promedio fue de 117,440.89 pesos mexicanos. El 82.35% fue dictaminado como prevenible. El personal médico en formación estuvo involucrado en el 58.82%, y el 14.7% del total de los eventos ocurrió en otro hospital.

ConclusionesEs necesario analizar los eventos adversos graves en un hospital de enseñanza para aprender e implementar intervenciones para prevenir y mejorar la seguridad de los pacientes. Los costos directos derivados de un evento adverso grave en México son similares a lo reportado en países desarrollados.

Patients who go to hospitals in search of curative services may have to face one or more adverse events, which can be of a mild, moderate or severe magnitude according to the international classification of the World Health Organisation.1 This can lead to a longer hospital stay, increased morbidity and mortality, as well as increased total cost of hospitalisation, which in most cases result in costs to the public healthcare system, the patient or both.

In 1999 with the publication of “To err is human: Building a safer health system”, an important step towards the occurrence of adverse events arising from medical care was taken, when it was reported that the United States of America reached figures of up to 98,000 annual deaths.2 In 2004, the World Health Organisation promoted the World Alliance for Patient Safety in order to co-ordinate and direct strategies focused on safer health care.3 In 2005, Spain conducted the national study on adverse events related to hospitalisation and helped to document the reality of that country.4 Finally, in 2011, the iberoamerican study of adverse events was published, with the participation of Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, Peru and Argentina, and a prevalence of 10% was observed in adverse events resulting from medical care.5

In a fragmented health system like that of Mexico, made up of private and the public sectors and in which, in the latter sector, at least 7 different institutions provide medical care,6 the absence of guidelines for systematic care means there is a predisposition to errors and adverse events of varying magnitude. In 2008, the National Centre for Health Technology Excellence implemented the creation of clinical practice guidelines, so that health care service providers could adapt and adopt them, with the aim of reducing the variability currently observed.7

This study was conducted over a period of one year at a second level general hospital with specialisms in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. The hospital has 250 hospital beds and 139 transient beds, and, in 2012, made 17,420 hospital discharges. It is considered the hospital with the highest resolution rate in the central-north region of the country. In addition, it serves as a place for clinical training for 19 medical specialisms and sub-specialisms, as well as for five degrees in the area of health with more than 400 students.

The goal of this study was to identify the total number of severe adverse events, as well as the direct costs to the hospital. Prior to conducting this study, no published studies documenting the costs of severe adverse events were found in Mexico.

Materials and methodsA systematic review of severe adverse events was conducted during the period 1 January to 31 December, 2012. The events were identified by the Departamento de Calidad y Seguridad del Paciente of the hospital. To support what was published in other countries, it was decided to classify events according to the five areas of hospitalisation: General Medicine, Paediatrics, Surgery, Traumatology, and Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The Departamento de Calidad y Seguridad del Paciente collected information according to internal hospital protocol. The reporting procedure includes a form to be completed, which is delivered by means of two methods: (1) post box for reporting events and (2) the reports delivered directly to the department; in both cases, the report could be made anonymously.

The report included the following information: name of the person reporting or anonymous, work area, date of the event, time of event occurrence, hospital shift in which it occurred, location of the hospital where the event occurred, the patient's name, patient identification, age, gender, hospitalisation area, number of beds, admission diagnosis and whether he or she was accompanied by a relative at the time of the adverse event. Also, it requested that a brief description of the event be included.

The information was reviewed, confirmed and analysed by the staff of the Departamento de Calidad y Seguridad del Paciente, which consists of the Deputy Director of Quality and Patient Safety, a doctor with over 30 years of clinical and administrative experience, a doctor's assistant with 5 years of medical-administrative experience, 3 registered nurses with more than 15 years of clinical and administrative practice, an individual with an administrative degree with 4 years in the department and an intern from the social medical service.

All cases, according to hospital internal protocol, were analysed using the Ishikawa or “fishbone” tools and, after a systematic and thorough investigation, it was determined whether they were an error or an adverse event, as well as their classification according to the Classification of the World Health Organisation.1 A severe adverse event was defined as “an event that results in death or loss of a body part, or disability, or loss of a bodily function that lasts more than 7 days, or is still present at the time of discharge from the medical care centre for hospitalised patients, or when referred to as severe”.1

For the purpose of this study, only severe adverse events were included. The direct hospital costs were determined from the time of occurrence of the adverse event until discharge or death. The individual costs for each event were provided by the Division of Financial Resources of the hospital, according to the 2012 tab. The costs included inputs and services as follows: hospitalisation, medication, diagnostic tests, human resources and all elements used as a result of the adverse event. In addition, it was decided to show the costs in local currency and in Dollars. The annual average exchange rate was used to estimate the exchange rate during the year 2012, which was 1 American Dollar=13.16 Mexican Pesos, for this period of time.8

Information analysisTo integrate and analyse the information, a database with the information collected was created. The data analysis was reviewed to identify possible inconsistencies and aberrant errors, using the statistical package STATA v.11. Quantitative variables were described using measurements of central tendency and dispersion. The proportions were used to describe the qualitative variables. The Student's t-test was used to calculate the mean difference of the quantitative variables.

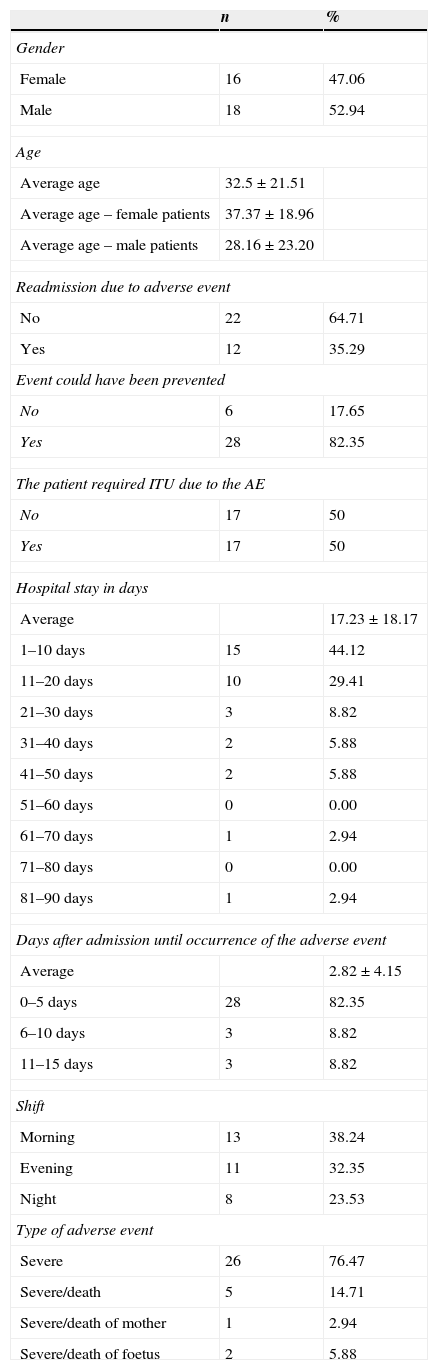

ResultsIn the period between 1 January and 31 December, 2012, information related to 34 severe adverse events in a community teaching hospital in San Luis Potosi, Mexico was obtained. The main characteristics of the events analysed are shown in Table 1.

Main characteristics of severe adverse events.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 16 | 47.06 |

| Male | 18 | 52.94 |

| Age | ||

| Average age | 32.5±21.51 | |

| Average age – female patients | 37.37±18.96 | |

| Average age – male patients | 28.16±23.20 | |

| Readmission due to adverse event | ||

| No | 22 | 64.71 |

| Yes | 12 | 35.29 |

| Event could have been prevented | ||

| No | 6 | 17.65 |

| Yes | 28 | 82.35 |

| The patient required ITU due to the AE | ||

| No | 17 | 50 |

| Yes | 17 | 50 |

| Hospital stay in days | ||

| Average | 17.23±18.17 | |

| 1–10 days | 15 | 44.12 |

| 11–20 days | 10 | 29.41 |

| 21–30 days | 3 | 8.82 |

| 31–40 days | 2 | 5.88 |

| 41–50 days | 2 | 5.88 |

| 51–60 days | 0 | 0.00 |

| 61–70 days | 1 | 2.94 |

| 71–80 days | 0 | 0.00 |

| 81–90 days | 1 | 2.94 |

| Days after admission until occurrence of the adverse event | ||

| Average | 2.82±4.15 | |

| 0–5 days | 28 | 82.35 |

| 6–10 days | 3 | 8.82 |

| 11–15 days | 3 | 8.82 |

| Shift | ||

| Morning | 13 | 38.24 |

| Evening | 11 | 32.35 |

| Night | 8 | 23.53 |

| Type of adverse event | ||

| Severe | 26 | 76.47 |

| Severe/death | 5 | 14.71 |

| Severe/death of mother | 1 | 2.94 |

| Severe/death of foetus | 2 | 5.88 |

ITU: intensive therapy unit; AE: adverse event.

Severe adverse events accounted for 0.19% of all hospital discharges in 2012. In the study, there was no significant difference due to patients’ gender. About 52.94% of the subjects (18 severe adverse events) were male patients and 47.06% (16 severe adverse events) were female patients.

The overall average age (±standard deviation) was 32.5 years (±21.51). For female patients, it was 37.37 years (±18.96) and for male patients, it was 28.16 years (±23.20) (p=0.1090).

The average number of days between admission and the time of occurrence of the severe adverse event was 2.82 days (±4.15). About 82.35% (28 severe adverse events) occurred during the first 5 days after admission.

Readmission as a consequence of severe adverse events amounted to 35.29% (12 events).

Of the 34 cases reported, 38.24% (13 severe adverse events) occurred in the morning shift, 32.35% (11 severe adverse events) in the evening shift and 23.53% (8) in the night shift.

The hospital direct cost of 34 severe adverse events analysed was 3,992,988.51 Mexican pesos (303,418.58 US dollars). The average per event was 117,440.89 Mexican pesos (8924.08 US dollars), with a minimum of 2864.66 Mexican pesos (217.68 US dollars) and a maximum of 479,722.93 Mexican pesos (36,453.11 US dollars). These are shown in Fig. 1.

Since this is a reference hospital, it was established that 14.7% (5 severe adverse events) of the events occurred in other hospital centres and were taken to this hospital.

About 82.35% (28 severe adverse events) were identified as preventable. Undergraduate and graduate medical staff took part in 58.82% of severe adverse events (20 events).

Also, in 50% of the cases (17 events), the Intensive Care Unit was required as a result of the severe adverse events. The mean length of stay was 17.23 days (range 0–83 days).

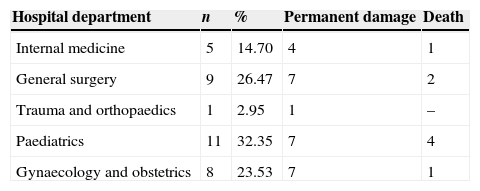

In 76.47% of the cases (26 events), permanent impairment occurred, and in 23.53% of the cases (8) the severe adverse event contributed to the death of the patient. The hospitalisation service and the consequences of the events are presented in Table 2.

DiscussionIn a health system in its early stages of change in the quality of culture and patients’ safety, severe adverse events are identified as a priority over mild and moderate events. Therefore, events of smaller magnitudes can be set aside. This study showed that the hospitalised population that suffered from a severe adverse event was in the economically productive age group (mean 32.5±21.51 years), but with no significant difference due to gender (p=0.1090).

Furthermore, 82.35% of severe adverse events occurred during the first 5 days of hospitalisation, which indicates that prolonged hospitalisation does not necessarily lead to damage as a result of the health care process.

The study results show that there was a readmission percentage of 35% due to severe adverse events, which almost doubles what was reported in the iberoamerican study of adverse events, in which the percentage amounted to 18%.5 The difference between studies may be explained because, in this study, only severe adverse events were included, over a period of one year.

The extension of the hospital stay following a severe adverse event may range from a short period of time which could be minutes, hours, or weeks to several months.9,10 In the American region, the average length of stay in patients who suffered some kind of adverse event was 16 days,5 unlike the length recorded in our study, which was 17.23 days, as shown by the results. However, during the study, there was one case of an 83-day hospitalisation. Although 44% of the cases (15 cases) showed a hospital stay between 1 and 10 days, it is should be noted that 33.3% of the cases (5 cases) were due to death.

In contrast to what was reported in another study in which most adverse events occurred during the night shift,11 in this study severe events reported during the morning shift were 38%, while those reported during the night shift amounted to 23%. It should be stated that adverse events of the same magnitude occurred in other shifts, but were not reported.

It is imperative to mention that 50% of the patients who experienced a severe adverse event required admission to the Intensive Care Unit. This represented an increase in direct hospital costs and a reduction in space for other critical patients.

The average cost per severe adverse event was 117,440.89 Mexican pesos (8924.08 US dollars), ranging from 2864.66 to 479,722.93 Mexican pesos (217.68 to 36,453.11 US dollars) and is similar to that reported in other studies.12–14 Nevertheless, in a developing country like Mexico, the direct hospital cost is higher than in developed countries.

Although it was not the purpose of the study, an emerging category was identified which made it possible to identify that a percentage of 60.5% of the total budget spent on the 34 cases was covered by the System of Social Protection of Health, and 39.5% became social expenditure. In Mexico, this means a non-refundable expense that results in a budget deficit for the hospital.

In this study, it was possible to identify 5 severe adverse events that occurred in other hospitals and which, at the request of patients or relatives, were taken to the community teaching hospital. Two cases originated in public hospitals and 3 cases in private hospitals. This accounted for 14.7% of the cases and 1,045,068.9 Mexican pesos (79,412.53 US dollars) which corresponded to 26% of the direct cost for the hospital. Similarly, a portion of this budget was undertaken by the Social Protection System in Health and by social expenditure.

This study showed that 82.35% of severe adverse events could have been prevented, unlike the iberoamerican study of adverse events, in which only 64% of the events could have been prevented.5 This can be explained by the context in which this study took place. Nevertheless, in 2008, Ruelas Barajas et al. reported that up to 87% of the cases were preventable.15

In health-care training institutions, undergraduate and graduate medical personnel perform procedures supervised by senior medical consultants. Nevertheless, in the present study using the “fishbone” tool, it was determined that, even with supervision in 58.82% of the cases, trainees conducting some type of procedure caused the patient to suffer a severe adverse event, and the existing hospital barriers could not prevent the damage. This may be a weakness in most health-care training institutions in Mexico, and further research on mentoring and effective medical supervision is required.

Finally, it is important to state that, in all hospitals, particularly in teaching hospitals, the quality of culture and patients’ safety should be strengthened to minimise the damage that could result from medical inattention rather than from the underlying disease itself.

ConclusionsThis study highlights the importance of analysing severe adverse events as a systematic part of teaching in hospitals, and the urgent need to eliminate the “blaming and shaming” culture. The public health care system in Mexico is still vulnerable to the occurrence of severe adverse events and their high costs. It is important to strengthen an effective tutorial teaching in all areas of the hospital. Currently, the World Health Organisation has recommended a curricular guideline for the inclusion of patient safety in teaching.16 These results may also guide hospital planners and managers who face economic and developmental circumstances similar to those faced in Mexico.

LimitationsNo estimations have been made for the cost of the damage and suffering caused to patients, their families and the health care personnel involved, or for its impact on corporate image. It is very likely that other similar severe adverse events occurred in the five hospital departments and were not reported.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

We thank Dr. Brian Schwartz, associate professor in Dalla Lana School of Public Health of Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Dr. Veronika Wirtz, professor in the Department of International Health of the University of Boston; medical students: Gamaliel Aguilera Barragán Pickens, María Isabel Jasso Ávila, Ricardo Álvarez Villanueva, Viviana Juárez Cruz and an anonymous collaborator from the United Kingdom.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez-Mendoza LM, Torres-Montes A, Soria-Orozco M, Padrón-Salas A, Ramírez-Hernández ME. Costos de eventos adversos graves en un Hospital Comunitario de Enseñanza en México. Cir Cir. 2015;83:211–6.