Psycho-COVID: Long-term effects of COVID19 pandemic on brain and mental health

Más datosThe COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health issues in healthcare workers which in turn impacts their quality of life.

ObjectiveThis review aimed to (i) analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of healthcare professionals and (ii) identify the associated factors with quality of life.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a systematic review using the PRISMA guidelines previously registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021253075). The searched in Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases included original articles published till May 2021.

ResultsWe found 19 articles and 14,352 professionals in total, the median age ranged from 29 to 42.5 years and 37% of the studies used the WHOQOL-BREF instrument to assess the outcome. The report was heterogeneous, 7 studies described global scores and 9 by domains. Depression, anxiety and stress were commonly reported factors affecting professional's quality of life and this was significantly lower among professionals working with COVID-19 patients compared to their counterparts.

ConclusionCOVID-19 frontline workers perceived lower quality of life, which was mainly associated with psychological states such as the aforementioned besides to working conditions like not being previously trained in COVID-19 cases. On the other hand, social support, resilience and active coping could improved their quality of life.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha agravado los problemas de salud del personal sanitario, lo que a su vez repercute en su calidad de vida.

ObjetivoEsta revisión tiene como objetivo: (a) Analizar el impacto de la pandemia COVID-19 en la calidad de vida de los profesionales sanitarios y (2) Identificar los factores asociados a su calidad de vida.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una revisión sistemática utilizando las pautas PRISMA previamente registradas en PROSPERO (CRD42021253075). La búsqueda en las bases de datos Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE y EMBASE incluyó artículos originales publicados hasta mayo de 2021.

ResultadosSe encontraron 19 artículos y 14.352 profesionales en total, la mediana de edad osciló entre 29 y 42,5 años y el 37% de los estudios utilizaron el instrumento WHOQOL-BREF para evaluar el resultado. El informe fue heterogéneo, 7 estudios describieron puntuaciones globales y 9 por dominios. La depresión, la ansiedad y el estrés fueron los factores comúnmente reportados que afectan a la calidad de vida del profesional, y esta fue significativamente menor entre los profesionales que trabajan con pacientes de COVID-19 en comparación con sus homólogos.

ConclusiónLos trabajadores de primera línea de COVID-19 percibieron una menor calidad de vida, que se asoció principalmente a estados psicológicos como los mencionados, además de a condiciones de trabajo como no haber recibido formación previa en casos de COVID-19. Por otro lado, el apoyo social, la resiliencia y el afrontamiento activo mejoraron su calidad de vida.

The global disease outbreak of COVID-19, caused by acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), has triggered an international health emergency.1 As of early August, 2022 more than 593 million cases have been identified worldwide, being the so-called most vulnerable groups, formed by collectives with the highest-risk of contracting illnesses, elderly people with comorbidities or without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation, the most affected by COVID-19 and its long-term sequelae.2–6

The healthcare workers (HCWs) as part of the frontline are considered a risk group due to in-hospital exposure to transmission, contagion by SARS-CoV-2 virus, and the difficult working conditions they face daily such as the inadequate distribution of personnel protective equipment (PPE), lack of medical equipment (mechanical ventilators) and the precarious infrastructure of hospitals.5,7–9 These characteristics, added to the isolation restrictions, have impacted in HCW’ lifestyles10 increasing anxiety, depression, occupational stress levels and sleep disorders.11,12 A systematic review showed moderate pooled-prevalence of 23.21% and 22.8% for anxiety and depression in HCW, respectively.13 Consequently, these adverse effects affects their health, the quality of healthcare services12 and leads to a decline in their quality of life (QOL).14

The QOL is considered as a multidimensional concept product of the individual's perception in the context of their culture and affected by great variety of factors.15 One of these factors is the state of health which refers to the consequences or repercussions of the disease in the life of the individual, being identified as health-related quality of life (HRQOL).16,17 In this sense, since health is a crucial factor and subset of QOL, in this review these terms are considered synonymous.

The health impact of COVID-19 can negatively influence the quality of life of HCWs and possible associated factors, so it is important to identify sequelae and prioritize mental health interventions.16 So that, this study aims to systematically (1) analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the QOL of healthcare professionals and (2) identified the associated factors with the QOL of HCWs in this context.

Material and methodsEligibility criteriaWe included all articles (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort study designs), that reported QOL in HCWs involved in care and assessment of patients, during the pandemic and published till May, 2021. Articles that individually reported mental or physical health outcomes among healthcare personnel on remote working, non-observational studies and proceedings articles were excluded.

Information sources and search strategyWe registered the protocol in PROSPERO under the registration code CRD42021253075. We comprehensively performed and developed search strategies in MEDLINE/EMBASE (through Ovid), Web of Science databases and Scopus using Medical Subheading terms (MeSH), emtree terms and free terms for other bases. Additionally, we included only studies conducted in English language, with publication dates between January 1, 2020 and May 24, 2021. The included studies were validated by D.V.Z. More details can be found in supplementary material 1.

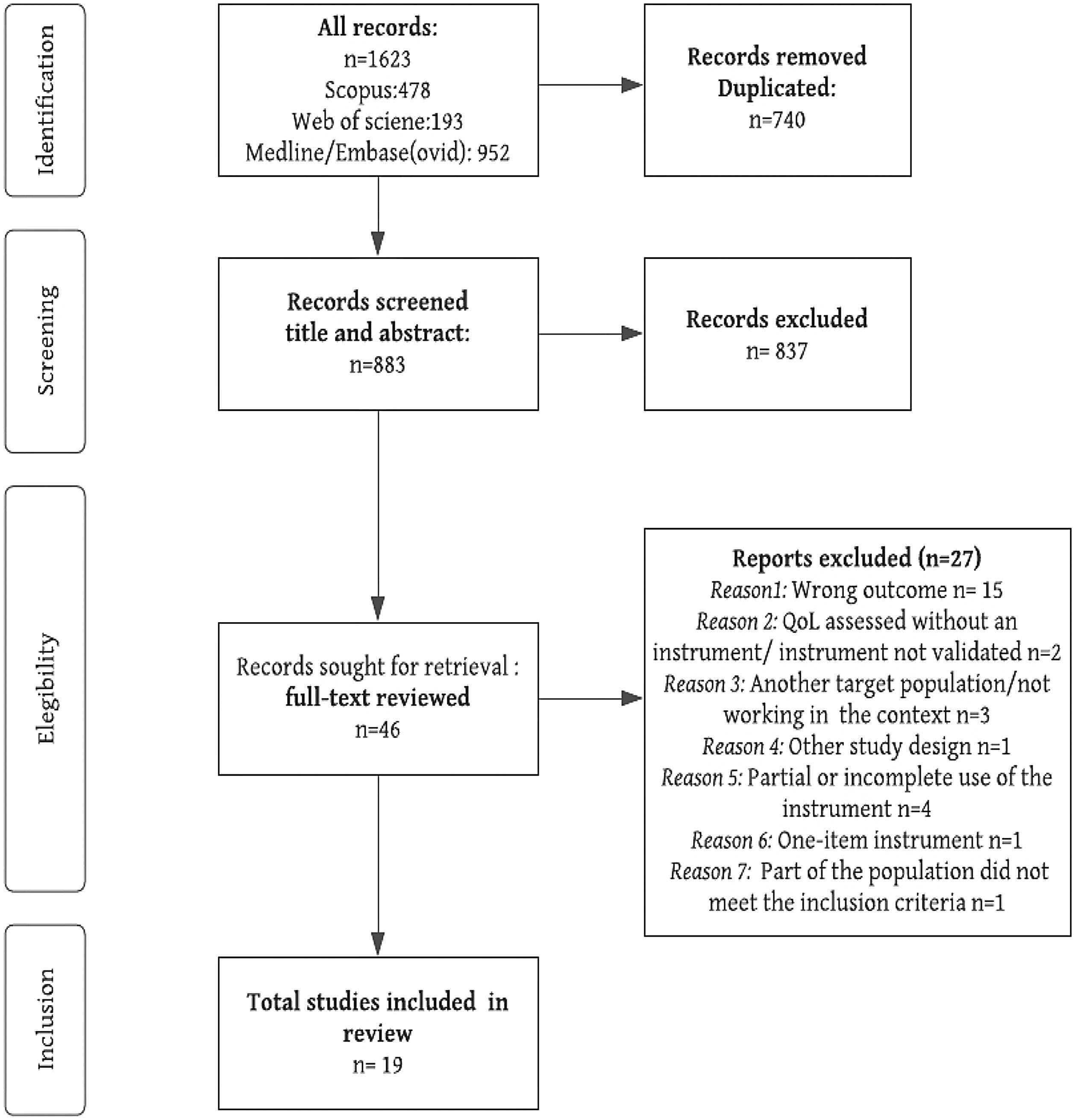

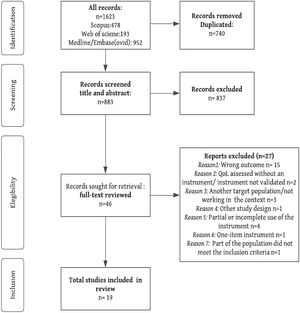

Selection processAfter the literature search, duplicate records were removed with Zotero (https://www.zotero.org/) and the studies were examined to identify relevant articles in Rayyan web application (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar Foundation, Qatar; see https://rayyan.qcri.org). Due to the large number of records, three pairs of independent reviewers (A.C./L.C.A., C.M.R.R./M.B., and G.C./A.L.V.E.) screened the titles and abstracts, after a pilot testing process to standardize inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by an independent reviewer (D.V.Z.). Thereafter, full texts of relevant studies were assessed for eligibility. The complete list of excluded articles at this stage is available in supplementary material 2.

Data analysisThree independent researchers (L.C.A., M.B., A.L.V.E.) extracted the following information from each of the included studies: first author, year of publication, study design, country, income-economy classification according to the World Bank18 and participant's characteristics (age, sex, profession). In addition, information regarding the outcome of interest was extracted: QOL instrument, scores, and associated factors. In case of disagreement, full-text articles were checked by the reviewers and discussed until a consensus was reached. The synthesis was carried out according with the “General Synthesis Framework” of the Cochrane Handbook.

Risk of biasThree independent researchers (L.C.A., A.C., C.M.R.R.) assessed the risk of bias (RoB), and any disagreement was resolved by an expert author (D.V.Z.). The RoB of cross-sectional studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist. The JBI checklist for cross-sectional studies included eight items that assess eligibility criteria, sample description, exposure measure, standard criteria for measurement of condition, identification and strategies to deal with confounding factors, outcome measurement and statistical analysis.19

ResultsA total of 1623 records were identified. After removing duplicate records, a total of 740 unique records were found. Following a further review by title and abstract, only 19 full-text cross-sectional studies were included in this review. The selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

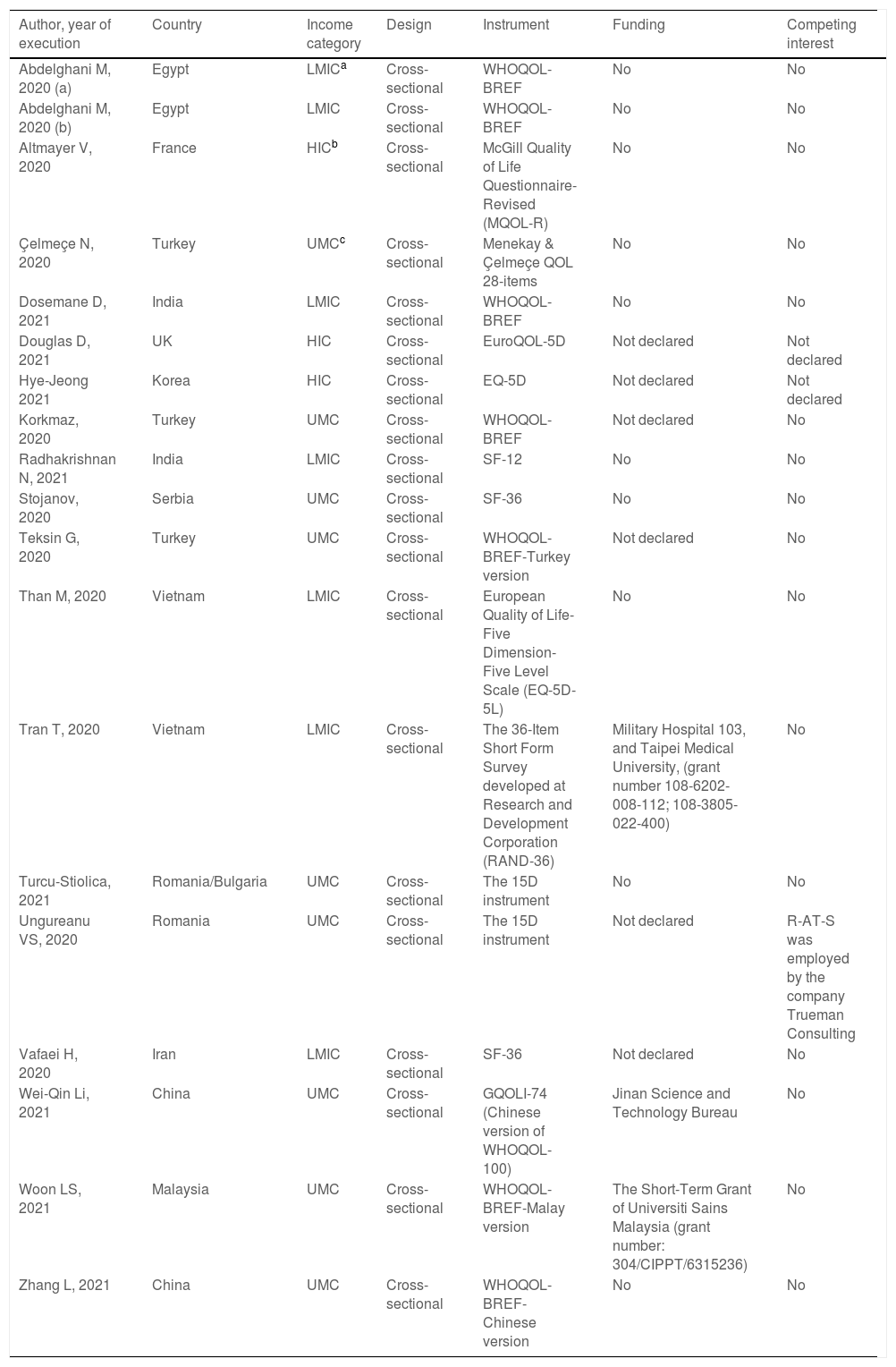

Study characteristicsTable 1 shows the characteristics of the 19 studies. Three of the studies20–22 were conducted in countries from the Middle East and North Africa, 811,23–29 in Europe and Central Asia, 630–35 in East Asia and Pacific, and only 236,37 in the South Asia region. Moreover, seven articles were from low-middle-income countries (LMIC), nine from upper-middle-income countries (UMC) and three from high-income countries (HIC). Turkey had the highest number of publication (n=3) followed by China (n=2). One study also included both countries: Romania and Bulgaria.28

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year of execution | Country | Income category | Design | Instrument | Funding | Competing interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelghani M, 2020 (a) | Egypt | LMICa | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF | No | No |

| Abdelghani M, 2020 (b) | Egypt | LMIC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF | No | No |

| Altmayer V, 2020 | France | HICb | Cross-sectional | McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire-Revised (MQOL-R) | No | No |

| Çelmeçe N, 2020 | Turkey | UMCc | Cross-sectional | Menekay & Çelmeçe QOL 28-items | No | No |

| Dosemane D, 2021 | India | LMIC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF | No | No |

| Douglas D, 2021 | UK | HIC | Cross-sectional | EuroQOL-5D | Not declared | Not declared |

| Hye-Jeong 2021 | Korea | HIC | Cross-sectional | EQ-5D | Not declared | Not declared |

| Korkmaz, 2020 | Turkey | UMC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF | Not declared | No |

| Radhakrishnan N, 2021 | India | LMIC | Cross-sectional | SF-12 | No | No |

| Stojanov, 2020 | Serbia | UMC | Cross-sectional | SF-36 | No | No |

| Teksin G, 2020 | Turkey | UMC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF-Turkey version | Not declared | No |

| Than M, 2020 | Vietnam | LMIC | Cross-sectional | European Quality of Life-Five Dimension-Five Level Scale (EQ-5D-5L) | No | No |

| Tran T, 2020 | Vietnam | LMIC | Cross-sectional | The 36-Item Short Form Survey developed at Research and Development Corporation (RAND-36) | Military Hospital 103, and Taipei Medical University, (grant number 108-6202-008-112; 108-3805-022-400) | No |

| Turcu-Stiolica, 2021 | Romania/Bulgaria | UMC | Cross-sectional | The 15D instrument | No | No |

| Ungureanu VS, 2020 | Romania | UMC | Cross-sectional | The 15D instrument | Not declared | R-AT-S was employed by the company Trueman Consulting |

| Vafaei H, 2020 | Iran | LMIC | Cross-sectional | SF-36 | Not declared | No |

| Wei-Qin Li, 2021 | China | UMC | Cross-sectional | GQOLI-74 (Chinese version of WHOQOL-100) | Jinan Science and Technology Bureau | No |

| Woon LS, 2021 | Malaysia | UMC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF-Malay version | The Short-Term Grant of Universiti Sains Malaysia (grant number: 304/CIPPT/6315236) | No |

| Zhang L, 2021 | China | UMC | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF-Chinese version | No | No |

Regarding QOL assessment, 7 of the studies used the WHOQOL-BREF instrument, 2 used the 15D instrument,28,29 3 used the EuroQoL-5D25,30,31 and another 3 used the SF-36/RAND.22,26,29 The remaining studies used the McGill QOL Questionnaire-Revised Menekay & Çelmeçe QOL 28 items,24 SF-1237 and the GQOLI-74.33 Two of the studies did not include a statement on competing interest,25,38 only one reported a potential conflict of interest and three studies reported on having funding.32–34

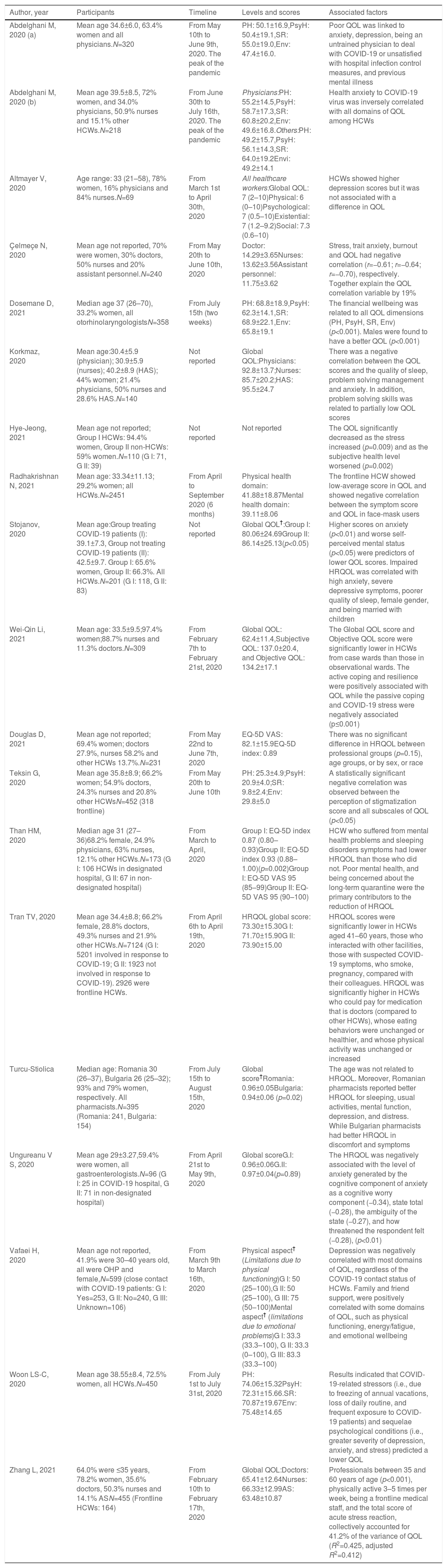

Population characteristicsThere were 14,352 HCWs and 39 non-HCWs in the 19 studies. The frontline HCWs were 8344 in total (see Table 2). The mean age or median of age was mentioned in 13 studies, and the participant's age ranged from 29.0 to 42.5 years. The percentage of women in these studies ranged from 29.2% to 97.4%. The HCWs were physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, laboratory technicians, dietitians, and obstetric personnel.

The main characteristics of participants and QOL associated factors in the included studies.

| Author, year | Participants | Timeline | Levels and scores | Associated factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelghani M, 2020 (a) | Mean age 34.6±6.0, 63.4% women and all physicians.N=320 | From May 10th to June 9th, 2020. The peak of the pandemic | PH: 50.1±16.9,PsyH: 50.4±19.1,SR: 55.0±19.0,Env: 47.4±16.0. | Poor QOL was linked to anxiety, depression, being an untrained physician to deal with COVID-19 or unsatisfied with hospital infection control measures, and previous mental illness |

| Abdelghani M, 2020 (b) | Mean age 39.5±8.5, 72% women, and 34.0% physicians, 50.9% nurses and 15.1% other HCWs.N=218 | From June 30th to July 16th, 2020. The peak of the pandemic | Physicians:PH: 55.2±14.5,PsyH: 58.7±17.3,SR: 60.8±20.2,Env: 49.6±16.8.Others:PH: 49.2±15.7,PsyH: 56.1±14.3,SR: 64.0±19.2Envi: 49.2±14.1 | Health anxiety to COVID-19 virus was inversely correlated with all domains of QOL among HCWs |

| Altmayer V, 2020 | Age range: 33 (21–58), 78% women, 16% physicians and 84% nurses.N=69 | From March 1st to April 30th, 2020 | All healthcare workers:Global QOL: 7 (2–10)Physical: 6 (0–10)Psychological: 7 (0.5–10)Existential: 7 (1.2–9.2)Social: 7.3 (0.6–10) | HCWs showed higher depression scores but it was not associated with a difference in QOL |

| Çelmeçe N, 2020 | Mean age not reported, 70% were women, 30% doctors, 50% nurses and 20% assistant personnel.N=240 | From May 20th to June 10th, 2020 | Doctor: 14.29±3.65Nurses: 13.62±3.56Assistant personnel: 11.75±3.62 | Stress, trait anxiety, burnout and QOL had negative correlation (r=−0.61; r=−0.64; r=−0.70), respectively. Together explain the QOL correlation variable by 19% |

| Dosemane D, 2021 | Median age 37 (26–70), 33.2% women, all otorhinolaryngologistsN=358 | From July 15th (two weeks) | PH: 68.8±18.9,PsyH: 62.3±14.1,SR: 68.9±22.1,Env: 65.8±19.1 | The financial wellbeing was related to all QOL dimensions (PH, PsyH, SR, Env) (p<0.001). Males were found to have a better QOL (p<0.001) |

| Korkmaz, 2020 | Mean age:30.4±5.9 (physician); 30.9±5.9 (nurses); 40.2±8.9 (HAS); 44% women; 21.4% physicians, 50% nurses and 28.6% HAS.N=140 | Not reported | Global QOL:Physicians: 92.8±13.7;Nurses: 85.7±20.2;HAS: 95.5±24.7 | There was a negative correlation between the QOL scores and the quality of sleep, problem solving management and anxiety. In addition, problem solving skills was related to partially low QOL scores |

| Hye-Jeong, 2021 | Mean age not reported; Group I HCWs: 94.4% women, Group II non-HCWs: 59% women.N=110 (G I: 71, G II: 39) | Not reported | Not reported | The QOL significantly decreased as the stress increased (p=0.009) and as the subjective health level worsened (p=0.002) |

| Radhakrishnan N, 2021 | Mean age: 33.34±11.13; 29.2% women; all HCWs.N=2451 | From April to September 2020 (6 months) | Physical health domain: 41.88±18.87Mental health domain: 39.11±8.06 | The frontline HCW showed low-average score in QOL and showed negative correlation between the symptom score and QOL in face-mask users |

| Stojanov, 2020 | Mean age:Group treating COVID-19 patients (I): 39.1±7.3, Group not treating COVID-19 patients (II): 42.5±9.7. Group I: 65.6% women, Group II: 66.3%. All HCWs.N=201 (G I: 118, G II: 83) | Not reported | Global QOL†:Group I: 80.06±24.69Group II: 86.14±25.13(p<0.05) | Higher scores on anxiety (p<0.01) and worse self-perceived mental status (p<0.05) were predictors of lower QOL scores. Impaired HRQOL was correlated with high anxiety, severe depressive symptoms, poorer quality of sleep, female gender, and being married with children |

| Wei-Qin Li, 2021 | Mean age: 33.5±9.5;97.4% women;88.7% nurses and 11.3% doctors.N=309 | From February 7th to February 21st, 2020 | Global QOL: 62.4±11.4,Subjective QOL: 137.0±20.4, and Objective QOL: 134.2±17.1 | The Global QOL score and Objective QOL score were significantly lower in HCWs from case wards than those in observational wards. The active coping and resilience were positively associated with QOL while the passive coping and COVID-19 stress were negatively associated (p≤0.001) |

| Douglas D, 2021 | Mean age not reported; 69.4% women; doctors 27.9%, nurses 58.2% and other HCWs 13.7%.N=231 | From May 22nd to June 7th, 2020 | EQ-5D VAS: 82.1±15.9EQ-5D index: 0.89 | There was no significant difference in HRQOL between professional groups (p=0.15), age groups, or by sex, or race |

| Teksin G, 2020 | Mean age 35.8±8.9; 66.2% women; 54.9% doctors, 24.3% nurses and 20.8% other HCWsN=452 (318 frontline) | From May 20th to June 10th | PH: 25.3±4.9;PsyH: 20.9±4.0;SR: 9.8±2.4;Env: 29.8±5.0 | A statistically significant negative correlation was observed between the perception of stigmatization score and all subscales of QOL (p<0.05) |

| Than HM, 2020 | Median age 31 (27–36)68.2% female, 24.9% physicians, 63% nurses, 12.1% other HCWs.N=173 (G I: 106 HCWs in designated hospital, G II: 67 in non-designated hospital) | From March to April, 2020 | Group I: EQ-5D index 0.87 (0.80–0.93)Group II: EQ-5D index 0.93 (0.88–1.00)(p=0.002)Group I: EQ-5D VAS 95 (85–99)Group II: EQ-5D VAS 95 (90–100) | HCW who suffered from mental health problems and sleeping disorders symptoms had lower HRQOL than those who did not. Poor mental health, and being concerned about the long-term quarantine were the primary contributors to the reduction of HRQOL |

| Tran TV, 2020 | Mean age 34.4±8.8; 66.2% female, 28.8% doctors, 49.3% nurses and 21.9% other HCWs.N=7124 (G I: 5201 involved in response to COVID-19; G II: 1923 not involved in response to COVID-19). 2926 were frontline HCWs. | From April 6th to April 19th, 2020 | HRQOL global score: 73.30±15.30G I: 71.70±15.90G II: 73.90±15.00 | HRQOL scores were significantly lower in HCWs aged 41–60 years, those who interacted with other facilities, those with suspected COVID-19 symptoms, who smoke, pregnancy, compared with their colleagues. HRQOL was significantly higher in HCWs who could pay for medication that is doctors (compared to other HCWs), whose eating behaviors were unchanged or healthier, and whose physical activity was unchanged or increased |

| Turcu-Stiolica | Median age: Romania 30 (26–37), Bulgaria 26 (25–32); 93% and 79% women, respectively. All pharmacists.N=395 (Romania: 241, Bulgaria: 154) | From July 15th to August 15th, 2020 | Global score†Romania: 0.96±0.05Bulgaria: 0.94±0.06 (p=0.02) | The age was not related to HRQOL. Moreover, Romanian pharmacists reported better HRQOL for sleeping, usual activities, mental function, depression, and distress. While Bulgarian pharmacists had better HRQOL in discomfort and symptoms |

| Ungureanu V S, 2020 | Mean age 29±3.27,59.4% were women, all gastroenterologists.N=96 (G I: 25 in COVID-19 hospital, G II: 71 in non-designated hospital) | From April 21st to May 9th, 2020 | Global scoreG.I: 0.96±0.06G.II: 0.97±0.04(p=0.89) | The HRQOL was negatively associated with the level of anxiety generated by the cognitive component of anxiety as a cognitive worry component (−0.34), state total (−0.28), the ambiguity of the state (−0.27), and how threatened the respondent felt (−0.28), (p<0.01) |

| Vafaei H, 2020 | Mean age not reported, 41.9% were 30–40 years old, all were OHP and female,N=599 (close contact with COVID-19 patients: G I: Yes=253, G II: No=240, G III: Unknown=106) | From March 9th to March 16th, 2020 | Physical aspect† (Limitations due to physical functioning)G I: 50 (25–100),G II: 50 (25–100), G III: 75 (50–100)Mental aspect† (limitations due to emotional problems)G I: 33.3 (33.3–100), G II: 33.3 (0–100), G III: 83.3 (33.3–100) | Depression was negatively correlated with most domains of QOL, regardless of the COVID-19 contact status of HCWs. Family and friend support, were positively correlated with some domains of QOL, such as physical functioning, energy/fatigue, and emotional wellbeing |

| Woon LS-C, 2020 | Mean age 38.55±8.4, 72.5% women, all HCWs.N=450 | From July 1st to July 31st, 2020 | PH: 74.06±15.32PsyH: 72.31±15.66.SR: 70.87±19.67Env: 75.48±14.65 | Results indicated that COVID-19-related stressors (i.e., due to freezing of annual vacations, loss of daily routine, and frequent exposure to COVID-19 patients) and sequelae psychological conditions (i.e., greater severity of depression, anxiety, and stress) predicted a lower QOL |

| Zhang L, 2021 | 64.0% were ≤35 years, 78.2% women, 35.6% doctors, 50.3% nurses and 14.1% ASN=455 (Frontline HCWs: 164) | From February 10th to February 17th, 2020 | Global QOL:Doctors: 65.41±12.64Nurses: 66.33±12.99AS: 63.48±10.87 | Professionals between 35 and 60 years of age (p<0.001), physically active 3–5 times per week, being a frontline medical staff, and the total score of acute stress reaction, collectively accounted for 41.2% of the variance of QOL (R2=0.425, adjusted R2=0.412) |

PH: physical health domain; PsyH: psychological health domain; SR: social relationship domain; Env: environmental domain; QOL: quality of life; HRQOL: health-related quality of life; HCWs: healthcare workers; EQ-5D VAS: EuroQoL-5D Visual analog scale; EQ-5D index: EuroQoL summary index; OHP: obstetric healthcare personnel; AS: auxiliary staff including technical executives; HAS: healthcare assistant staff.

The report of QOL using the mean or median was diverse. Two studies reported the global QOL mean for physicians, nurses, and healthcare assistants as 65.41–92.80, 66.33–85.60, and 63.48–95.50, respectively. For comparison by domains, 5 of the studies reported values ranging from 25.3 to 74.06, 20.9 to 72.31, 9.8 to 70.87, and 29.8 to 75.48 for physical, psychological, social and environmental health, respectively.20,21,27,34,36 One study had scores under each domain's mean27 and at least four studies scored over 50 points.20,21,34,36

The 15D instrumentThe HRQOL mean in the pharmacist population from Romania and Bulgaria were significantly different (0.956±0.051 vs 0.936±0.063, p=0.002), respectively.28 Some domains as sleeping, usual activities, mental function, depression, and distress domains were significantly better in Romanian pharmacists while discomfort and symptoms were worse.28 Moreover, the gastroenterologists from designated COVID-19 hospitals had lower mean than their counterparts, but this was not statistically significant (p=0.888).29

SF-36/RAND-36Main findings suggest that HCWs treating COVID-19 patients, present lower QOL compared to their colleagues (80.06 vs 86.14) (p<0.05). This difference was particularly noticeable for the vitality and mental health dimensions.26 Similar results showed limitations due to physical health and emotional problems among obstetric professionals compared to those working with unknown contact COVID-19 patients.22

EuroQOLThe overall HRQOL mean was 82.1, summary index was 0.89, and this was not different between professionals’ groups, age, sex, or race.25 The summary index was lower than general population under COVID-19 (0.95)39 but higher than patients suffering from diabetes (0.8)40 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (0.8)41 skin diseases (0.73),42 respiratory diseases (0.66),43 dengue fever (0.66),44 frail elderly (0.58)45 and elderly after fall injury (0.46)46 and fracture injuries (0.23).47 In addition, HCWs who suffered from mental health problems and sleeping disorders symptoms had a higher risk of having lower HRQOL scores than those who did not. Similarly, those who experienced higher level of stress and poorer level of perceived subjective health had a greater risk of having lower HRQOL scores than those who did not.30

Other instrumentsIn other studies, a median QOL of 7 was considered a good score in HCWs working regularly in the Intensive Care Unit compared to reinforcement HCW, assessed using the McGill Quality of Life-Revised.23 In addition, using the SF-12 questionnaire, Radhakrishnan et al.37 reported a below average QOL in frontline HCWs, 41.88±18.87 and 39.11±?8.06 for physical and mental composite, respectively. Besides, the comparison study between clinical symptoms scores and comorbidities showed a negative correlation, with lower scores among face-mask users.

Furthermore, Wei-Qin33 assessed QOL using GQOLI-74 and showed that HCWs from confirmed case wards had significantly lower QOL than those working in observational wards. The value was better in HCWs who were above 45 years, married with children and those who earned a high income. Using the Menekay & Çelmeçe QOL 28-items tool, Çelmeçe,24 this highlighted a moderate, negative correlation between stress, trait anxiety, burnout and QOL.

Factors associated with quality of life in the COVID-19 contextSeveral differences in associated factors were reported. There were positive elements related to the QoL of health workers that were grouped into individual factors: quality of sleep,11 resilience, active coping style,33 food habits and physical activity,32 psychosocial factors: perceived support from family or social and friends, years of experience36 and economic factors: income, access to medication,33 financial stability.36

On the other hand, most of the studies showed non-positive factors that led to a decrease in QOL. These factors included: (a) mental health factors: severity of anxiety,20,21,26,29,34,48 worse self-perception of mental health,26 depression,20,22,26,34 burnout syndrome,48 greater severity of stress,30,48 insomnia,31 pre-existing mental illness20; (b) psychosocial factors: stigmatization27 and stress because of annual leave being frozen,34 (c) physical factors: comorbidities,32 presence of COVID-19 related symptoms37; (d) COVID-19 related factors: anxiety, fear and stress because of COVID-19,21,33 being worried about quarantine,31 loss of daily routine,34 and (e) individual factor: smoking habits.32 Also, some working COVID-19 factors were laboring in COVID-19 departments,11 working with COVID-19 confirmed cases,33 designated hospitals, being in the frontline37 or having no training in managing COVID-19 cases.20 Finally, a relevant economic factor was lower financial wellbeing perception.36 Considering that the studies presented results by workplace, treating COVID-19 patients, or being involved in responses to the COVID-19 as studies that assess QOL in frontline HCW, frontline condition had significantly lower QOL compared to other work modalities.26,33,35,37,48

In addition, some factors were associated with QOL but others were not, for instance, being married and having children (p<0.05) or just having children,24 was associated with better QOL scores in workers in close contact with COVID-19 patients. However, another study showed that marital status was not (p=0.145).24 Additionally, better QOL was mainly reported in females24 and nurses.33 By contrast, other findings suggest that females had lower QOL36 or being a female was neither positively nor negatively associated with QOL. The differences in scores by profession were not also significantly associated with QOL (p=0.114). Finally, participants >45 or 60 years had better scores33,34,36 but other studies reported that being over 30 years,31 or being between 41 and 60 years32 could be a factor for less QOL. In contrast, two of the studies reported that younger HCWs (<30 years) had lower mean QOL compared to the elderly.28,36 More details in Table 2.

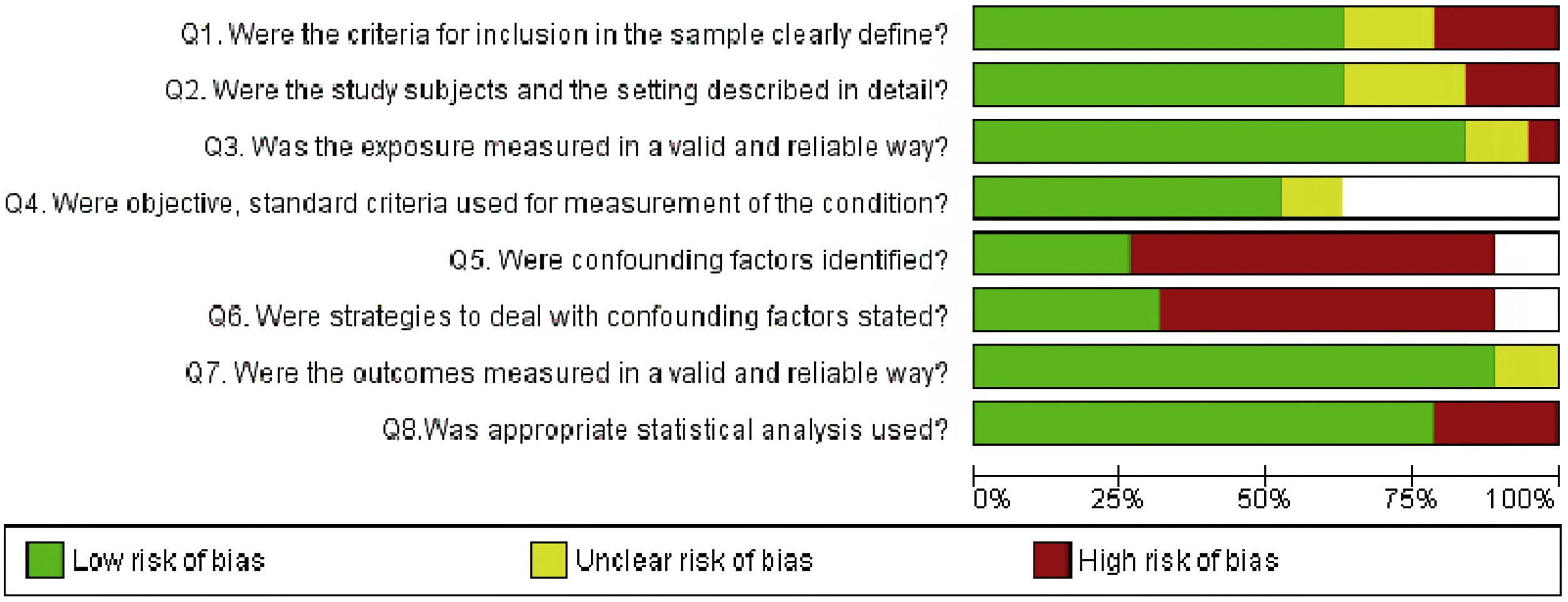

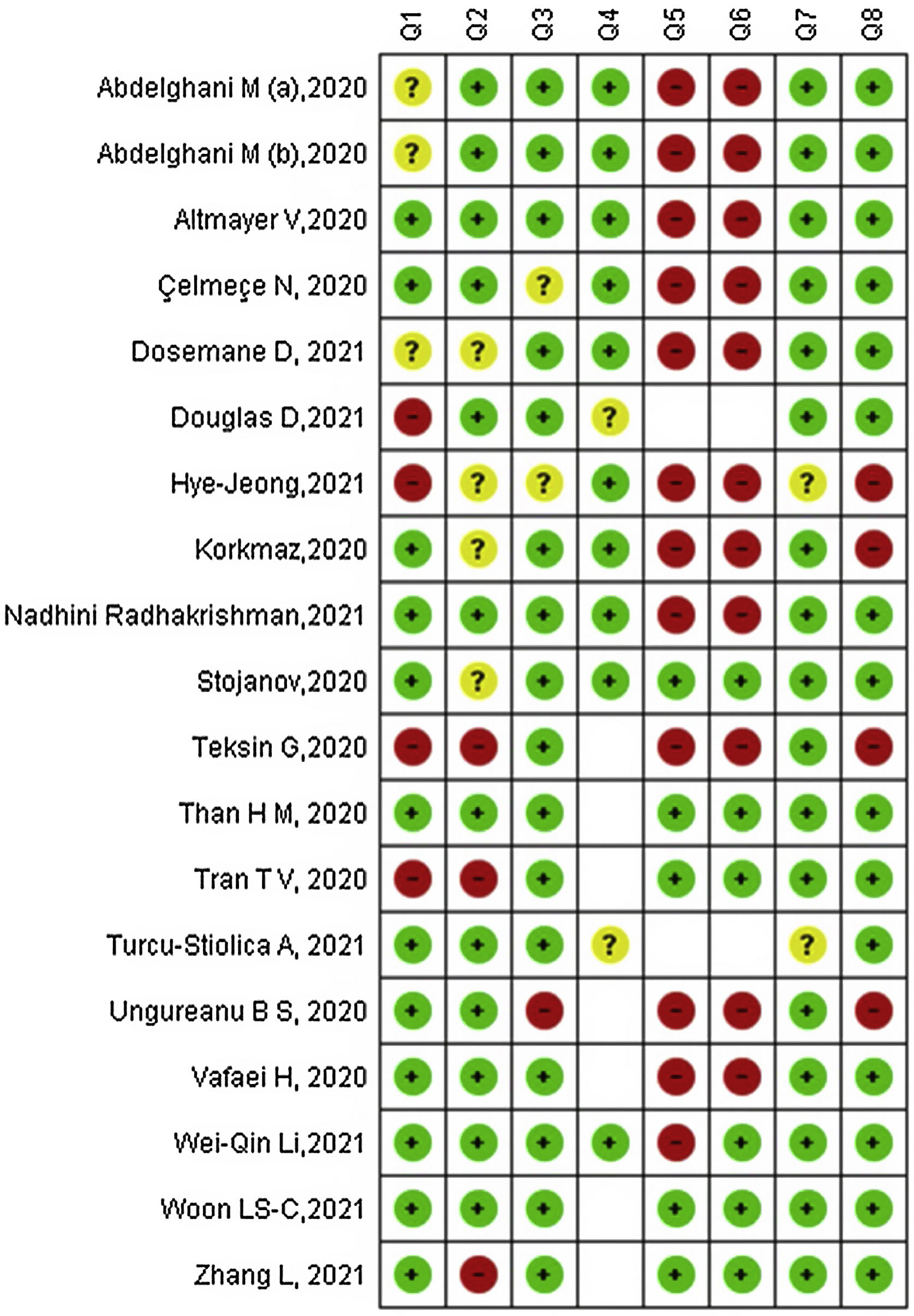

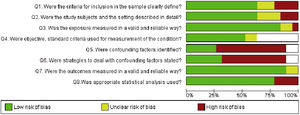

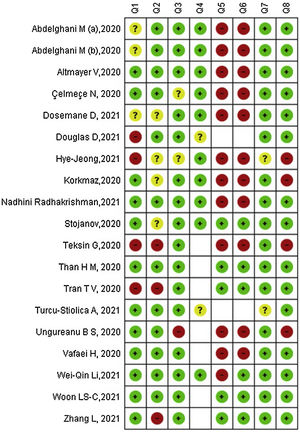

Risk of bias in studiesOur RoB assessment found that majority of the studies adequately met three criteria: the outcome was measured validly and reliably (94.7%; 18/19), the exposure was measured in a valid and reliable way (84.2%; 16/19) and the statistical analysis methods were adequate (78.9%; 15/19). However, several studies identified a high-risk of bias in confounders that were not adequately identified (57.9%; 11/19) and strategies not put in place to address these confounders (52.6%; 10/19). Details in Fig. 2.

The studies by Woon et al.34 and Than et al.31 had the lowest RoB, both for the seven low-RoB criteria and one criterion which was not applicable. The other two studies with a reasonable RoB were the study by Stojanov et al.26 with seven low-RoB criteria and one unclear RoB criterion; followed by Zhang et al.35 with six low-RoB criteria, one high-risk criterion, and one not applicable item. On the other hand, we identified three studies with the highest RoB: Teksin et al.27 with five high-RoB criteria; Hye-Jeong et al.30 with four high-RoB and three unclear RoB criteria; and Ungureanu et al.29 with four high-RoB criteria (see Fig. 3).

DiscussionCurrently, QOL is understood from various theories and perspectives, which incorporates three sciences: social, economic and medicine, each one of these develops a different point of view on how to conceptualize the QOL, generating a great dispersion and diversity of conceptions.49 Due to this heterogeneity, it is a challenge to unify findings and factors related to it.

We included nineteen cross-sectional studies that evaluated QOL and associated factors in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies were wide-ranging, used convenient sample and presented a low-RoB in terms of validity and reliability of exposure and outcome but high-risk identifying confounders. The evidence suggests a detrimental QOL of HCWs, mainly among frontline, independent of profession. This was associated with individual, psychosocial, mental health, physical health, COVID-19 related factors, working COVID-19 factors and economic issues, which had either positive or negative influence. What else sociodemographic features as age, sex and marital status might influence in both ways.

Our findings suggest that HCWs in close contact with COVID-19 patients experience high stress symptoms,33,36 depression25,29,34 and anxiety.20,29,34 This may be related to (a) the presence of physical and mental symptoms, where previous studies reported that when HCW's develop any symptoms such as throat pain, headache, cough, insomnia, etc. they face the fear of have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the stigma that comes with it and the fact of being able to infect their relatives, such worrisome thoughts would lead to their somatization increasing their psychological distress with adverse health consequences,50,51 followed by (b) the increase in demand of care and volume of patients, especially during the peaks of the first and second waves, and (c) the high demand and concentration that physically and mentally exhaust HCW, which exceed their autonomy and skills under high pressure situations breaking the balance between job demands and control level52 impairing their QOL.

If we take into account the WHO definition for QOL, this is a state of general wellbeing that includes objective descriptors and subjective evaluations of physical, material, social and emotional aspects, along with personal development and mediated by personal values. From this, QOL relies on the trade-off between subjective and objective conditions such as comorbidities, previous mental illnesses, stigmatization, working with COVID-19 cases, anxiety because of COVID-19, etc.53 So, it is not surprising that workers with poor perception of their individual, working25 and economic36 conditions perceived a poor QOL. For instance, findings related to working COVID-19 factors showed that being a frontline HCW32,37 not being satisfied with hospital measures or having no previous training on COVID-19 was associated with poor QOL. These are supported by previous reports in a similar context and the actual evidence suggests that untrained frontline HCWs in isolation wards perceive worse life and working conditions and high-risk of developing unfavorable mental health outcomes.54–57 This could prompt fall into a cycle of adverse feedback, leading to worse QOL.

Moreover, the increase in sleep disruptions as insomnia in HCWs could be related to large exposure to COVID-19 patients, who are subject of great emotional burden or even associated with parental stress in those having children.25 The last one could be related to the perceived inability to cover responsibilities and difficult access to family support,58 which could also be a factor for sleep disorders in parents affecting their wellbeing. These reinforce the need to provide special protection measures for frontline HCWs, with a consideration of family role in QOL. Regarding this, currently the digital cognitive-behavioral intervention aimed at insomnia (d-CBT I) has demonstrated its efficacy in reducing the number of insomnia symptoms as well as being cost-effective. Thus, this may be considered as an affordable strategy in order to mitigate the issues and related stressors that would trigger sleep problems in the context of COVID-19.59–61

However, this review found that HCWs are not only exposed to factors that negatively influence QOL. Elements such as resilience, active coping style and perceived social and relatives support increased QOL.62 This highlights the role of resilience as a coping strategy,63 which is crucial for QOL by ensuring less distress.64 Studies in this context recognize the importance of resilience as a determining factor in the mental health of HCWs.65,66 Thus, they encourage its reinforcement along with active coping strategies,65 good quality of sleep, positive affective state and life satisfaction as the mainstay to build resilient skills9,65–67 and the main source to deal with mental issues as well as having a positive impact on health. Consequently, those having better coping strategies, good quality of life and satisfaction will show better resilient skills and management of adverse events, and so have better QOL. Additionally, several factors could help reducing the likelihood that HCWs would experience a detrimental in QOL. First one through the improvement of the implementation of organizational prevention measures such as the practice of hand hygiene, wearing PPE, reduce gatherings in workplace, concern of health status of healthcare professionals and secondly, guaranteeing the access to vaccination and boosters on time.50,51 These measures might reduce the negative psychological states as anxiety, stress and improve trusting in health authorities.

Implications for future researchThese findings11,20,21,29,31,33–35 showed that mental health issue was one of the major contributors to the reduction in QOL, followed by working characteristics of frontline HCWs. In this context, implementing interventions in mental health and psychological support (SMAPS, in Spanish)68 as well as reducing work schedules, and maintaining security and safety standards at workplace will help to reduce working risk factors, thereby enabling protection of the health of the workers and improve their QOL.

Moreover, it is recommended for the different labor sectors, especially in the health sector through Occupational Medicine to implement surveillance and prevention programs for the mental and physical health of the worker in order to raise awareness, provide and intervene in the development of mental disorders that may affect the QOL of the staff.

Strengths and limitationsThe studies had some limitations. Some of the included studies used a small sample size and convenience sampling, which difficult the generalizability of the results. The data was mainly collected through online surveys, due to the pandemic context, which might have introduced a selection bias. Additionally, some studies selected HCWs from one hospital, or province and some studies did not have enough participants of both genders. Nine studies had HCWs in direct contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases, who are consequently under more stressful environment than others, conditioning their response when working in a more hostile space and being surrounded by adverse conditions. This review might also be limited because it included only studies in English language and excluded qualitative studies, so that relevant studies in other languages and based on other paradigms could have been omitted.

On the other hand, QOL assessment considered fulfilled conceptual dimensions suggested by the WHO (physical, mental, and social dimensions) but there was high heterogeneity regarding the type of instruments used. This is expected because of recommendations on assessing health outcomes through reliable instruments, and since there is no consensus in QOL assessment, there is no gold standard instrument. Also, these studies were peer-reviewed, done in different countries and represent the first attempt to describe QOL in HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, we included studies that used full instruments, in order to obtain a better proxy of QOL. Thus, we encourage researchers to develop a meta-analysis by including studies with the same measure.

ConclusionThis systematic review described the impact in HCWs QOL during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as identified the associated factors in COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers. We found nineteen studies, which presented mix findings in terms of RoB, and that evaluated QOL in HCWs where evidence suggests that frontline healthcare personnel had lower QOL than their counterparts and this is related to psychosocial, working COVID-19 factors, physical and mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, occupational stress, individual and previous mental illnesses. However, social support, resilience, and active coping boosted QOL, but no difference by profession.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, L.C.A., D.V.Z., H.C.; methodology, L.C.A., D.V.Z., C.M.R.R.; selection process and data curation, M.B., G.C., A.C.L., A.L.V.E.; risk of bias, L.C.A., C.M.R.R., A.C.L.; data interpretation, A.L.V.E., M.B., D.V.Z., G.C.; draft preparation, all authors; writing-review and editing, supervision and monitoring, A.C.L., L.C.A., all authors and main responsibility of D.V.Z., L.C.A., A.C.L., M.B. All authors have read and approved to the publish version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.