Suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury behavior are serious public health problems among adolescents. A significant proportion of adolescents evaluated in clinical settings meet criteria for the dysregulation profile (DP). DP is characterized by restlessness, irritability, “affective storms‿, mood instability, and aggression in a disproportionate grade to the situation. This DP might be related to increased risk of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors.

MethodsTwo hundred and thirty-nine adolescents from the Child and Adolescent Outpatient Psychiatric Services of the Jimenez Diaz Foundation, Madrid, were assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire-Dysregulation Profile, the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview and socio-demographic questionnaires.

ResultsLogistic regression showed that DP adolescents were at increased risk for suicide plans, gestures, and suicide attempts. They also tended to present more self-injurious behaviors than adolescents without DP.

ConclusionsOur results point to the role of self-regulatory problems in the presence of suicide plans, suicide gestures, suicide attempts, and in non-suicidal self-injury behavior. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the relationship between the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire-Dysregulation Profile and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors.

La ideación suicida, la conducta suicida y las conductas autolesivas sin intención suicida (autolesiones) son un grave problema de salud pública en la adolescencia. Una proporción significativa de de adolescentes evaluados en contexto clínico muestran un perfil de disregulación (DP). El DP se caracteriza por inquietud, irritabilidad, «tormentas afectivas», inestabilidad emocional y agresiones que aparecen de forma desproporcionada ante determinadas situaciones, y parece estar relacionado con un mayor riesgo de pensamientos y conductas suicidas y autolesivas.

MétodosDoscientos treinta y nueve adolescentes del Centro de Salud Mental Infantojuvenil del Servicio de Psiquiatría de la Fundación Jiménez Díaz fueron evaluados con la Escala de Fortalezas y Dificultades para obtener el DP y con la entrevista estructurada sobre suicidio y autolesiones; se recogió también información sociodemográfica.

ResultadosEstudios de regresión logística mostraron que los adolescentes con elevación del DP tenían más riesgo de presentar planes de suicidio, gestos suicidas e intentos suicidas. Igualmente, mostraron más riesgo de autolesiones.

ConclusionesLos resultados apuntan a dificultades de autorregulación tras la presencia de planes de suicidio, gestos suicidas, intentos de suicidio y autolesiones. De cara al futuro, estudios longitudinales permitirían esclarecer la dirección de dicha relación.

Suicidal behavior among adolescents (including suicide, suicide attempts, suicide gestures, and suicidal ideation) is a public health problem with serious impact on health and well-being. In recent years, this type of behavior has become more frequent and important, with more social consequences.1,2

Suicide is one of the main causes of death among adolescents in Europe3 and around the world.4 In Spain, suicidal prevalence has been increasing in the last years.5,6 Although adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems are at heightened risk for premature death from different causes, suicide mortality rates are still not carefully studied in this age group.7 Discrepancies in the study of adolescent suicide may be due in part to difficulties concerning the way in which different suicide and self-injury behaviors are defined.8 It is important to establish clear definitions distinguishing between self-injurious behaviors with an intention to die (suicidal behaviors) and those without this intention, called here non-suicidal self-injury behaviors (NSSI).9 Furthermore, it is also important to differentiate between distinct suicidal behaviors, such as suicidal ideations (thoughts of killing oneself), suicide plans (plans about how to kill oneself), suicide gestures (behaviors committed to lead others to believe one wanted to kill oneself when there is no intention of doing so), and suicide attempts (an actual attempt to kill oneself).8 Clarifying those concepts will allow both researchers and clinicians to detect the presence, frequency, and characteristics of different suicide and self-injurious behaviors among adolescents. It will also improve the identification of patients at risk and, therefore, the prevention of such dangerous behaviors.

It is clearly known that mental health problems in adolescents are a risk factor for suicide.7 In addition, a significant proportion of adolescents attending mental health services suffer from severe affective and behavioral dysregulation witch interferes with the diagnosis and prognosis. These patients usually show restlessness, irritability, “affective storms‿, mood instability, and aggression in a disproportionate grade to the situation. However, this dysregulation do not correspond with any of the diagnoses proposed by current classification systems.10,11 In light of this problem in the clinical setting, a dysregulation pattern was defined and assessed by elevations using three of the Child Behavior Check-list (CBCL12) syndrome scales: Aggressive behavior, Anxious/Depressed, and Attention problems.13 Investigations have showed that the DP could be interpreted as an index of self-regulatory problems in multiple domains.14

Investigation regarding the DP assessed by means of the CBCL (CBCL-DP) has been developed for the last two decades.13 Recently, it has also been described as a DP assessed by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ11,15). The SDQ has shown similar psychometric characteristics to the CBCL and seems to be of easier application.16–19 Studies using the SDQ-DP have proven its psychometric validity11,20 and found similar prevalence and correlates of psychopathology in DP patients as those of studies using the CBCL-DP.10

The DP has also proven to be related to functional impairment and symptom severity.20 Its presence in childhood and adolescence seems to be related to the development of psychopathology, mood and substance disorders, as well as personality disorder traits in adulthood.20–24 The relationship between suicide and the DP is however, to our knowledge, a little-studied field.

Studies examining the relationship between the CBCL-DP and suicidal behavior have shown a higher risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in children and adolescents with higher CBCL-DP scores. Significantly higher reports of suicidal behavior were also shown in the CBCL-DP group, from a clinical and non-clinical national sample of American adolescents aged between 11 and 18.20 A longitudinal study on a German clinical sample showed that cases reporting suicide attempts or acute suicidal ideation at age of 19 were significantly more prevalent with increasing CBCL-DP scores at the age of 8 and 11.22 The presence of the dysregulation profile, assessed with the CBCL-DP, was implicated as an indicator of more frequent and severe suicidal ideations in a large clinical sample of children and adolescents from 6 to 18 years old.24 Finally, in a 23-year long study of youth at risk for major mood disorder, participants with the CBCL-Pediatric Bipolar Disorder phenotype (which has been proved to be equivalent to dysregulation profile) exhibited increased rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors across development.25 These studies however, do not clearly differentiate between suicidal ideation and suicide plans, or between suicide gestures, suicide attempts and NSSI. As data suggest, the presence of DP impacts suicidal ideation type and severity. As a result, it is important to be able to distinguish the types of these suicidal behaviors involved in these studies. In addition, we have not found any article on the association between suicide and the SDQ-DP. The aim of the present study was to study the prevalence of suicide thoughts and behaviors in a clinical sample of adolescents in order to determine the relationship between the SDQ-DP, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. We posited that adolescents with higher levels of DP would display these thoughts and behaviors at a greater rate than their counterparts with lower levels of DP.

MethodsSampleTwo hundred and sixty-seven subjects were recruited from the Child and Adolescent Outpatient Psychiatric Services, Jiménez Díaz Foundation (Madrid, Spain) from November 1st 2011 to October 31st 2012. Exclusion criteria were restricted to age of patients (subjects under 11 years old and subjects over 18 years old), and patients’ and parents’ inability to comprehend the questionnaires used. Patients who did not complete the SDQ were also excluded. The final sample consisted of 239 subjects. Comparative analyses between the excluded patients and the final sample were conducted and no differences were found in the main psychosocial characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, negative live events, functional impairment, socioeconomic level, family organization, diagnosis, personal and familiar suicide history, suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide gestures, suicide attempts, and non-suicidal self injury) apart from the subscale “Thoughts of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury‿ of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI)8 (X2=3.875, Df=1, p=0.049).

Written informed consent was obtained from patients and parents or legally authorized representatives. The Jiménez Díaz Foundation Ethics Committee approved the study.

InstrumentsAll subjects were administered the Spanish version of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview, SITBI8,26: a structured interview that assesses the presence, frequency, and characteristics of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide gestures, suicide attempts and NSSI.

Parents or legally authorized representatives were administered the Spanish version of the Parents-Rated Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ.15 The SDQ is composed of 25 Likert-type items, divided into five scales. The first four scales measure emotional symptoms, behavioral problems, hyperactivity, and peer relationship problems while the fifth scale measures pro-social behaviors. A total difficulties score was generated by adding up items from the first four scales. The SDQ-DP is calculated from the Parent-Rated SDQ.11 It is comprised of two items of the SDQ emotional symptoms subscale, two of the conduct problems subscale, and one of the hyperactivity subscale. Overall, the SDQ-DP score is composed of the un-weighted sum of these five items. The cutoff point recommended to define the Parent-Rated SDQ-DP is ≥5 points (Sensitivity=94.6%; Specificity=80%; Cronbach's alpha=0.52).11 We used these criteria as defined by Holtmann11 to discriminate between adolescents with higher and lower rates of dysregulation (called DP and NO_DP group, respectively for easier reading).

The Stressful Life Events Scale27 was administered to obtain information regarding life stressors. In this case, adolescents respond as to whether a given negative life event had occurred in their lives in the last three years.

Demographic data, developmental features, and medical, family, psychiatric and treatment history were obtained through a semi-structured interview. Experienced clinicians also completed the Children's Global Assessment Scale, C-GAS.28 This scale yields a measure of the severity of a given patient's symptomatology.

Data analysisChi square and Student's t-test were used to test SDQ-DP differences regarding gender, age, demographic data, negative life events, self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and C-GAS.

Once the variables of interest were identified, we conducted a multiple step data analysis similar to Holtmann et al.22 Thus, logistic regression models were utilized to examine the association between the SDQ-DP and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. To clarify the predictive power of SDQ-DP on the variables studied, we conducted a two model regression analysis. In the first model, gender and negative life events were introduced as covariates to estimate the effect of the SDQ-DP independently from these potential confounders. The second model was also adjusted for the C-GAS score in order to control for the effect of poor level of functioning in the relationships.

ResultsSample featuresTwo hundred and thirty-nine subjects (63.6% males, CI: 57.33–69.44; 36.4% females, CI: 30.56–42.67) aged between 11 and 17 years old (M=14.11, Sd=1.92) took part in the present study. Most subjects were Caucasian (92.9%, CI: 83.12–91.42), lived with their family of origin (88.6%, CI: 83.12–91.42), and lived in a family with more than 2000 Euros/month of income (57.5%, CI: 50.34–64.41). 7.2% of subjects (CI: 4.99–11.09; n=17) were adopted and 43.2% (CI: 36.57–49.02; n=102) had repeated at least one scholar grade.

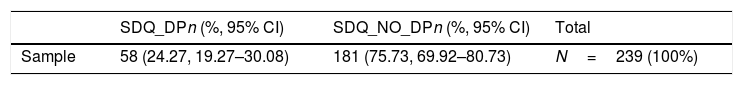

SDQ-DP comparison studies24.3% of the subjects (CI: 19.27–30.08; n=58) showed higher rates of DP (called the SDQ_DP group) and 75.7% of them (CI: 69.92–80.73; n=181) showed lower levels of DP (called the SDQ_NO_DP group). Socio-demographic results for both groups are reported in Table 1. Significant differences in gender (X2=6.473, df=1, p=0.011) were found. No other significant differences in the socio-demographic variables were found.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, categorized by SDQ-DP status.

| SDQ_DPn (%, 95% CI) | SDQ_NO_DPn (%, 95% CI) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 58 (24.27, 19.27–30.08) | 181 (75.73, 69.92–80.73) | N=239 (100%) |

| Mean (Sd) | Mean (Sd) | Mean (Sd) | t | Df | Student-t testp-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range: 11–17 years) | 14.23 (2.009) | 14.08 (1.899) | 14.11 (1.922) | −0.515 | 236 | 0.607 |

| n (%, 95% CI) | n (%, 95% CI) | n (%, 95% CI) | X2 | Df | Chi-squarep-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 6.473 | 1 | 0.011 | |||

| Male | 45 (77.6, 65.34–86.41) | 107 (59.1, 51.84–66.02) | 152 (63.6, 57.33–69.44) | |||

| Female | 13 (22.4, 13.59–34.66) | 74 (40.9, 33.98–48.16) | 87 (36.4, 30.56–42.67) | |||

| Obstetrical and new born complications | ||||||

| Prenatal (YES) | 31 (59.6, 40.8–65.67) | 79 (46.5, 36.63–50.93) | 110 (49.5, 39.82–52.36) | 2.752 | 1 | 0.097 |

| Peri-natal (YES) | 17 (32.1, 19.18–42.01) | 58 (33, 25.68–39.15) | 75 (32.8, 25.83–37.52) | 0.014 | 1 | 0.905 |

| Post natal (YES) | 2 (3.7, 0.95–11.73) | 13 (7.6, 3.82–11.23) | 15 (6.7, 3.84–10.1) | 1.003 | 1 | 0.317 |

| Ethnicity | 3.211 | 5 | 0.668 | |||

| Caucasian | 53 (96.4, 81.36–96.26) | 157 (91.8,81.03–90.93) | 210 (92.9, 83.12–91.42) | |||

| Latin American | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 1 (0.4, 0.07–2.33) | |||

| Asian | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 1 (0.4, 0.07–2.33) | |||

| Gipsy | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 2 (1.2, 0.3–3.94) | 2 (0.9, 0.23–3) | |||

| Black | 1 (1.8, 0.31–9.14) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 2 (0.9, 0.23–3) | |||

| Other | 1 (1.8, 0.31–9.14) | 9 (5.3, 2.64–9.18) | 10 (4.4, 2.29–7.53) | |||

| Academic performance | 1.795 | 1 | 0.180 | |||

| Repeated grades (YES) | 29 (50.9, 37.54–62.46) | 73 (40.8, 33.46–47.61) | 102 (43.2, 36.57–49.02) | |||

| Adopted | ||||||

| (YES) | 5 (8.8, 3.74–18.64) | 12 (6.7, 3.83–11.23) | 17 (7.2, 4.99–11.09) | 0.265 | 1 | 0.607 |

| Educational level (Mother) | 0.460 | 3 | 0.928 | |||

| No education | 3 (5.2, 1.77–14.14) | 6 (3.4, 1.53–7.04) | 9 (3.8, 1.99–7) | |||

| Primary | 11 (19, 10.93–30.85) | 32 (18, 12.81–23.89) | 43 (18, 13.64–23.36) | |||

| Secondary | 18 (31, 20.62–43.80) | 59 (33.1, 26.19–39.73) | 77 (32.6, 26.61–38.38) | |||

| University | 26 (44.8, 32.75–57.55) | 81 (45.5, 37.69–52.03) | 107 (45.3, 38.60–51.11) | |||

| Educational level (Father) | 4.369 | 2 | 0.113 | |||

| No education | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 6 (3.31, 1.53–7.04) | 6 (2.51, 1.16–5.37) | |||

| Primary | 13 (22.41, 13.59–34.66) | 26 (14.36, 10–20.22) | 39 (16.31, 12.17–21.53) | |||

| Secondary | 28 (48.27, 35.93–60.84) | 83 (45.85, 38.76–53.13) | 111 (46.44, 40.23–52.77) | |||

| University | 17 (29.31, 19.18–42.01) | 66 (36.46, 29.8–43.69) | 83 (34.72, 28.98–40.96) | |||

| Per capita income (euros per month) | 2.905 | 4 | 0.574 | |||

| More than 2500 | 14 (29.8, 14.96–36.53) | 48 (34.5, 20.62–33.39) | 62 (33.3, 20.8–31.85) | |||

| 2000–2500 | 12 (25.5, 12.25–32.77) | 33 (23.7, 13.29–24.5) | 45 (24.2, 14.38–24.26) | |||

| 1500–1999 | 8 (17, 7.16–24.93) | 22 (15.8, 8.17–17.72) | 30 (16.1, 8.94–17.35) | |||

| 500–1499 | 13 (27.7, 13.59–34.66) | 30 (21.6, 11.86–22.67) | 43 (23.1, 13.64–23.36) | |||

| Less than 500 | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 6 (4.3, 1.53–7.04) | 6 (3.2, 1.116–5.37) | |||

| Live with | 7.898 | 5 | 0.162 | |||

| Family of origin | 49 (84.5, 73.07–91.62) | 161 (89.9, 83.55–92.73) | 210 (88.6, 83.12–91.42) | |||

| Adoptive family | 5 (8.6, 3.74–18.64) | 12 (6.7, 3.83–11.23) | 17 (7.2, 4.49–11.09) | |||

| Relatives | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 3 (1.7, 0.57–4.76) | 3 (1.3, 0.43–3.62) | |||

| Institution | 3 (5.2, 1.77–14.14) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 4 (1.7, 0.65–4.22) | |||

| (Multiple) | 1 (1.8, 0.31–9.14) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 2 (0.9, 0.23–3) | |||

| Other | 0 (0.00, 0.0–0.62) | 1 (0.6, 0.1–3.06) | 1 (0.4, 0.07–2.33) | |||

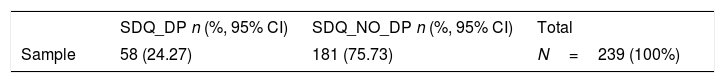

Prevalence rates of diagnosis are reported in Table 2, no significant differences in diagnosis distribution between groups were found (X2=6.169, df=5, p=0.290). Prevalence rates of the frequency of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors assessed with SITBI are reported in Table 2. DP group showed significantly higher prevalence in the subscales “Suicidal Ideation‿, “Suicidal Gestures‿, “Suicide Attempts‿, and “NSSI behavior‿.

Clinical characteristics of the sample, categorized by SDQ-DP status.

| SDQ_DP n (%, 95% CI) | SDQ_NO_DP n (%, 95% CI) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 58 (24.27) | 181 (75.73) | N=239 (100%) |

| n (%, 95% CI) | n (%, 95% CI) | n (%, 95% CI) | X2 | Df | Chi-squarep-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | 6.169 | 5 | 0.290 | |||

| Behavior Disorders | 41 (71.9, 59–81.9) | 123 (68.7, 61.5–75) | 164 (69.5, 63.3–75) | |||

| Emotional Disorders | 5 (8.8, 3.8–18.9) | 9 (5, 2.6–9.2) | 14 (5.9, 3.57–9.7) | |||

| Anxiety Disorders | 8 (14, 7.2–25.3) | 19 (10.6, 6.9–15.9) | 27 (11.4, 7.9–16.1) | |||

| Eating Disorders | 1 (1.8, 0.3–9.2) | 10 (5.6, 3.06–9.9) | 11 (4.7, 2.6–8.1) | |||

| Others | 2 (3.5, 0.9–11.9) | 8 (4.5, 2.2–8.5) | 10 (4.2, 2.3–7.6) | |||

| None | 0 (0, 0–6) | 10 (5.6, 3.06–9.9) | 10 (4.2, 2.3–7.6) | |||

| Total | 57 (24.2, 19.1–30) | 179 (75.8, 70–80) | 236 (100, 98–100) | |||

| Mean (Sd) | Mean (Sd) | Mean (Sd) | t | Df | Student-t testp-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-GAS | 61.91 (9.177) | 68.93 (10.929) | 67.23 (10.936) | 4.379 | 233 | <0.001*** |

| CDI | ||||||

| Dysphoria/Negative Mood | 70.03 (21.925) | 56.99 (26.115) | 60.17 (25.732) | −3.432 | 236 | 0.001** |

| Negative Self-esteem | 62.26 (27.149) | 42.08 (29.719) | 47.00 (30.326) | −4.550 | 232 | <0.001*** |

| Total | 64.66 (27.061) | 44.71 (31.476) | 49.57 (31.592) | −4.335 | 236 | <0.001*** |

| STAXI-NA | ||||||

| Trait Temper | 64.05 (29.611) | 53.56 (26.809) | 56.23 (27.859) | −2.440 | 214 | 0.016* |

| Trait Reaction | 55.71 (29.562) | 52.62 (30.264) | 53.41 (30.049) | −0.657 | 214 | 0.512 |

| Anger/Trait (Total) | 57.87 (31.341) | 49.11 (30.346) | 51.34 (30.768) | −1.833 | 214 | 0.068 |

| Externalization of anger | 56.22 (32.409) | 43.95 (31.296) | 47.07 (51.959) | −2.487 | 214 | 0.014* |

| Internalization of anger | 54.73 (33.865) | 43.17 (32.779) | 46.12 (33.364) | −2.238 | 214 | 0.026* |

| External control | 54.49 (38.529) | 63.67 (32.734) | 61.33 (34.443) | 1.714 | 214 | 0.088 |

| Internal control | 45.89 (33.617) | 61.50 (31.979) | 57.52 (33.036) | 3.084 | 214 | 0.002** |

| control total | 45.89 (34.712) | 61.28 (32.347) | 57.34 (33.568) | 2.987 | 213 | 0.003** |

| Stressful Life Events Scale | 7.50 (3.374) | 5.29 (3.728) | 5.84 (3.759) | −3.860 | 214 | <0.001*** |

Diagnosis (n=236); C-GAS: Children's Global Assessment Scale (n=235); CDI: Children's Depression Inventory (n=238); STAXI-NA: State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory for child and adolescent (n=216); Stressful Life Events Scale (n=216).

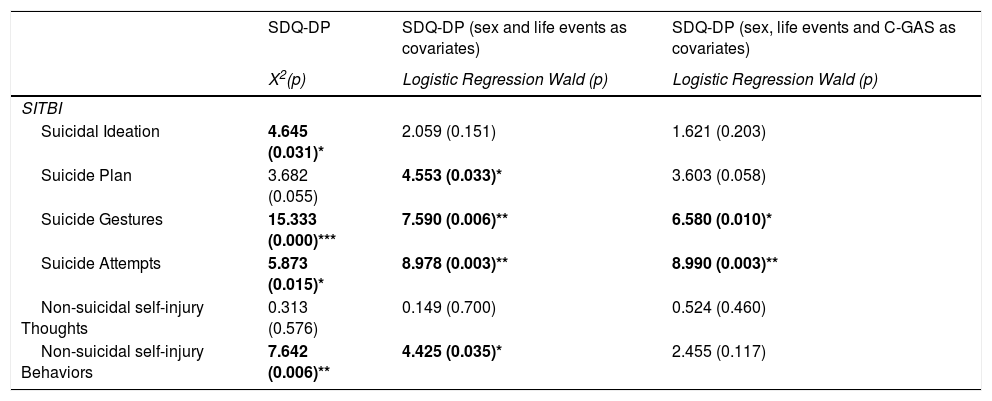

Results of logistic regression are summarized in Table 3. The logistic regression model, examining the relationship between the prevalence of SDQ-DP and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in the first model, was significant for the variables Suicide plan (t=4.553, df=1, p=0.033), Suicide gestures (t=7.590, df=1, p=0.006), Suicide attempts (t=8.978, df=1, p=0.003), and Self-Injury behaviors (t=4.425, df=1, p=0.035). Suicide gestures (t=6.580, df=1, p=0.010) and Suicide attempts (t=8.990, df=1, p=0.003) remained significant in the second model as well.

X2 and Logistic Regression between SDQ-DP and SITBI (sex and life events as covariates in the first model; C-GAS as covariate in the second model).

| SDQ-DP | SDQ-DP (sex and life events as covariates) | SDQ-DP (sex, life events and C-GAS as covariates) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| X2(p) | Logistic Regression Wald (p) | Logistic Regression Wald (p) | |

| SITBI | |||

| Suicidal Ideation | 4.645 (0.031)* | 2.059 (0.151) | 1.621 (0.203) |

| Suicide Plan | 3.682 (0.055) | 4.553 (0.033)* | 3.603 (0.058) |

| Suicide Gestures | 15.333 (0.000)*** | 7.590 (0.006)** | 6.580 (0.010)* |

| Suicide Attempts | 5.873 (0.015)* | 8.978 (0.003)** | 8.990 (0.003)** |

| Non-suicidal self-injury Thoughts | 0.313 (0.576) | 0.149 (0.700) | 0.524 (0.460) |

| Non-suicidal self-injury Behaviors | 7.642 (0.006)** | 4.425 (0.035)* | 2.455 (0.117) |

SDQ-DP: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Dysregulation Profile; SITBI: Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview.

We conducted a cross-sectional study in order to establish the prevalence of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in a clinical sample of adolescents with SDQ-DP, in comparison with adolescents without this profile.

The main findings were, firstly, that adolescents who met the DP exhibited significantly more suicide plans, suicide gestures, and suicide attempts than those who did not. These results are in line with previous literature20,22,24,25 that shows a relationship between the CBCL-DP and a higher risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. However, our findings are more specific in the kind of suicidal thoughts and behaviors related with DP. We distinguished between suicide plans, gestures and attempts. Furthermore, they highlight the role of self-regulatory problems in the presence of suicide plans, gestures, and attempts.14

Secondly, adolescents with higher levels of DP tended to present more NSSI behaviors than adolescents with lower levels of DP. This is a new finding, as previous studies about DP and self-injury did not differentiate between suicide behaviors, and NSSI behaviors and thoughts.13,20,22,24,25 To our knowledge, there are only two papers that have studied the relationship between NSSI behaviors and the SDQ, but not specifically with the SDQ-DP. These studies found a bidirectional relationship between psychopathology and NSSI only among girls29 and a relationship between psychological stress and NSSI among German adolescents.30 It is to be highlighted that the more hard and consistent association of DP group is with the suicide gesture and suicide attempts, while the association of DP group with suicide ideation, suicide plan and Non-suicidal self-injury behaviors is less consistent. That is to say that the DP group is associated hardly with impulsivity and behavior alterations (suicide attempts or gestures) but not so clearly with thoughts, plans or ideation.

Our results suggest that DP adolescents are at risk for more serious suicidal behaviors and thoughts, and NSSI behaviors. Adolescents with higher levels of DP are normally characterized by higher impulsivity and harm avoidance, as well as lower reward dependence and persistence.14 It may sound contradictory that people with higher harm avoidance are at risk for more serious self-injury behaviors. However, as DP adolescents seem to carry higher levels of mental suffering (in terms of psychopathological severity and psychosocial adversity), we posit that suicidal and NSSI behaviors are avoidance strategies of this mental suffering. Furthermore, high impulsivity, as a personality trait, is a well-known risk factor for many types of self-injurious behaviors. Low reward dependence and low persistence are probably hindering adolescents from learning more adaptive behavior and may also contribute to the development of future personality disorders.

The relationship between the DP and psychopathological severity, psychosocial adversity, difficulties in self regulation and functional impairment have been broadly studied with the CBCL-DP.14,20,22–25 Severe dysregulation has been linked to early temperament traits associated with future personality pathology features (namely, Cluster B personality disorders, hostility, impulsivity, and risk taking behaviors21,25,31).

Taking all the evidence together may take us thinking about new paths of interventions, related with development of behavioral and emotional regulation skills.

The findings of this study however, should be interpreted with caution. The instruments used are based on patients’ and parents’ reports, and no coefficient of agreement between interviewers’ diagnoses was computed. Incidentally, DP was assessed only with SDQ-DP and no CBCL-DP measure was taken. However, authors have pointed out the equivalence of both measures.16–19 Additionally, the clinical origin of the sample limits the generalizability of the findings. Finally, as these analyses are cross-sectional, it is difficult to establish the real direction of the relationship found however, the consistency of the results showed here with those of previous literature allows for interpreting the data.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study that has explored the relationship between the SDQ-DP and the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents. The fact that the SDQ-DP does have similar psychometric properties as the CBCL-DP and is shorter11,15,17,19,32 may make it preferable for use in clinical settings.17 It may be use as a screening tool due to its shortness, allowing clinicians identify risk cases where wider assessments were required. This study highlights the importance of early detection and intervention as to prevent type suicidal behaviors from occurring.

Roughly speaking, adolescents are a group that is at risk for suicidal behaviors.33 Those with mental health problems, especially emotional and behavioral problems, and those exposed to stressful life events and dysfunctional families4,7,34,35 are also at increased risk. Our findings are in line with those of previous studies, suggesting that severe dysregulation in adolescence is a risk factor for suicide plans, suicide gestures and suicide attempts, as well as for NSSI.

ConclusionDP assessed with the SDQ-DP is a useful tool to identify adolescents at risk for functional impairment, clinical severity, and suicide plans, gestures and/or attempts. It can be used as a brief questionnaire to assess overall severity in adolescents and can be completed with other specific tools (as the SITBI) in order to determine some risk behaviors.

It is of clinical interest to clearly differentiate those behaviors that exhibit intention to die from those that do not. It is also important to differentiate between suicidal ideation and suicide plans, since they are different risk factors for suicide.

Further investigation is needed in order to clarify the direction of the relationship between the SDQ-DP profile, and the answers to the SITBI in adolescents.

FundingThis study was partly supported by the Spanish Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AEPNYA).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Paloma Aroca and Lucia Albarracín for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Caro-Cañizares I, García-Nieto R, Díaz de Neira-Hernando M, Brandt SA, Baca-García E, Carballo JJ. El perfil de disregulación del SDQ y su relación con conductas y pensamientos de suicidio en adolescentes evaluados en contexto clínico. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019;12:242–250.