Involuntary admissions due to mental disorders occur with relative regularity in hospital admission units in our country. This work will study the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics found in relation to these type of patients, in order to have more information, both clinical and legal, with which to work and perform a better function, administration of resources, and development of necessary skills in these situations.

Material and methodsRetrospective descriptive observational study, in which different variables will be analyzed, previously selected, present in the population of psychiatric patients involuntarily admitted to the Doctor Negrín Hospital in a period of 2 years, 2019 and 2020, thus determining, the degree of prevalence of each of them.

ResultsAmong the variables most associated with involuntary admission are, being a man, in the fourth decade of life, single, without children, or employment, with a diagnosis of major psychotic or affective disorder who has most likely abandoned treatment.

DiscussionIt would be advisable to carry out a special follow-up of patients who meet the profile described above in order to minimize involuntary occurrence. It is necessary to develop educational, follow-up, and adherence programs within the reach of the population of psychiatric patients in order to minimize the need for involuntary admissions in our environment.

Los ingresos involuntarios por razón de trastorno psíquico se producen con relativa asiduidad en las unidades de internamiento hospitalarias de nuestro país. Este trabajo someterá a estudio las características socio-demográficas y clínicas que se encuentran en relación con este tipo de pacientes, para disponer de más información, tanto clínica como legal, con la que trabajar y desempeñar una mejor función, administración de recursos y desarrollo de habilidades necesarias ante estas situaciones.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo retrospectivo, en el cual se analizarán diferentes variables, seleccionadas previamente, presentes en la población de pacientes psiquiátricos ingresados involuntariamente en el Hospital Doctor Negrín en un período de tiempo de 2 años, 2019 y 2020, determinando así, el grado de prevalencia de cada una de ellas.

ResultadosEntre las variables más asociadas al ingreso involuntario se encuentran, ser varón, en la cuarta década de la vida, soltero, sin hijos, ni empleo, con un diagnóstico de trastorno psicótico o afectivo mayor que muy probablemente ha abandonado el tratamiento.

DiscusiónSería conveniente hacer un especial seguimiento a los pacientes que cumplan el perfil anteriormente descrito con el objetivo de minimizar la involuntariedad. Es necesario el desarrollo de programas educacionales, de seguimiento y adherencia al alcance de la población de pacientes psiquiátricos para así poder minimizar la necesidad de ingresos involuntarios en nuestro medio.

Involuntary admissions due to a psychiatric disorder occur relatively often in hospital internment units in our country. Depending on the population in question and the legal framework in each geographical region, certain clinical and sociodemographic patient profiles and characteristics are associated with poorer evolution and a higher rate of readmission.1–4

The criteria or indications for hospitalization are: the existence of a severe mental disorder, a risk for the moral or physical integrity of the patient or other people, and the urgent need for treatment. Nevertheless, Spain is an exception within the European legislative panorama, as the purpose of admission is exclusively therapeutic rather than preventive or punitive. Notwithstanding this, security measures involving a loss of freedom are sometimes used in cases where patients may commit crimes during an acute phase.3

Patients with a mental disorder are often erroneously considered to suffer a loss of cognitive capacity or sense of reality, so that they are thought to be incapable of intervening in decision-making. This (real or fictitious) attributed incapacity is at the root of intense debate in the fields of medicine and law, and involuntary admission is one of the most controversial aspects within this medical–legal context. As this conflict also involves the fundamental right to liberty (as expressed in article 17 of the Spanish Constitution), any decision must be subjected to a judicial guarantee, which is exclusively restricted to “authorizing” or “approving” the measure in question.6 On the other hand, although it is true that it violates the principle of patient autonomy, this is not the basis for the judicial intervention.5

Male individuals are closely associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, and patients of this type account for the majority of involuntary admissions.1,3–11 On the other hand, women are more likely to be interned6,12,13 due to emotional, personality, or behavioral disorders.1,2,14–16 This is probably because they tend to be better adjusted in social terms and make better use of healthcare services from earlier stages of any disease.14

The age group most likely to undergo involuntary admission is composed of subjects aged from 45 to 65 years old. This may be because individuals in these decades of life are obliged to face a series of events in life, such as responsibilities, stress, or family problems, which may trigger the disease which leads to admission.8

Other factors associated with a poor prognosis are a problematic economic situation, the lack of suitable community services or belonging to an ethnic minority.1,2,12,14,16,19

Involuntary hospitalization is often a traumatic experience for the patient and this may lead through extrapolation to a negative impression of all mental health services.1,4,17 This fact may cause a patient who has experienced admission to avoid all types of preventive community interventions, thereby creating a higher risk of re-admission.4,14,18

The legal frameworkTwo types of internment may occur:

Voluntary or agreed: non-judicial, established by direct contract between the patient and the medical institution, which both parties are able to rescind.

Involuntary, not agreed, or compulsory: in this form, it is also necessary to distinguish between penal and civil versions.

Involuntary internment is governed by art. 763 of the Civil Indictment Law:

“The internment, due to psychological disorder, of a person who is not able to decide on this for themselves, although they are subject to custody or guardianship, will require judicial authorization, which will be obtained from the court of the location where the individual affected by internment resides. The authorization will granted prior to the said internment, unless for reasons of urgency it were necessary to adopt the measure immediately. In this case, the person in charge of the centre in which the internment occurred will have to report this to the competent court as soon as possible and, in any case, within a period of twenty four hours, so that the said measure can be duly ratified, which must take place within a maximum period of seventy two hours from the moment court became aware of the internment […] (art. 763.1 LEC)”.

The criterion for involuntary internment is that “a person is not able to decide on this for themselves”, referring to the validity of consent or the capacity to issue valid consent. It may occur that a person is at risk of suffering a severe mental disorder requiring urgent treatment (indications for admission) and that they are able to decide on this themselves, that is, that they have the capacity to give their valid consent.

The precept will be applicable to adults as well as to minors or persons lacking legal capacity, without in the case of minors the consent of the parents being sufficient, nor the consent of the guardian in the case of persons lacking legal capacity. Nevertheless, the latter concept has disappeared with Law 8/2021, of 2 June, which reformed the civil and legal legislation for the support of persons unable to exercise their legal capacity, modifying art. 271 Código Civil in the following way: “any person of age or an emancipated minor, foreseeing the concurrence of circumstances that may hinder them in the exercise of their legal capacity in equality of conditions with others, may in public deed propose that one or several persons be named or excluded for the exercise of the function of guardian. They may also establish dispositions on the functioning and control of the guardianship and, especially, on the care of their person, rules for the administration and disposal of their goods, remuneration of the guardian, the obligation to make an inventory or dispensation of the same and measures for vigilance and control, as well proposing the persons who would have to undertake these measures”.

Depending on the moment when judicial authorization occurs, there are also 2 types of internment:

Ordinary: with the previous authorization of the Judge of First Instance of the place of residence of the person who requires internment.

Urgent: as decided by the medical professional and then ratified by the corresponding Judge of the location where the hospital is situated.

The steps to agree internment or ratify it are the same in both procedures: audience of the person affected by the decision, of the Fiscal Ministry and any other person whose appearance the judge deems convenient, or who is requested by the person affected by the measure, direct examination by the judge of the person whose internment is in question and audience of the ruling of a doctor designated by the judge. The decision of the jurist is of course liable to appeal. A period of 72 h is set to ratify an internment which has already occurred, given that the person interned has already been deprived of their freedom.

Art. 763 also stipulates the obligation of the medical personnel who attend the patient to regularly inform the court of the need to maintain the measure. A direct discharge is also possible followed by a report of the same to the judge. Art. 211 of the Civil Code (which governed involuntary internment prior to art. 763 of the LEC) did not refer to the possibility of direct discharge, and this modification is considered to be a major advance. The latter article makes it clear that the problem is obviously medical, so that the patient's health is the central concern. The end of internment should therefore occur at the very moment when the therapeutic utility of the same ceases.5,20

According to the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD), the prevalence of severe mental disorders (SMD) in the adult population of Europe stands at 27% (83 million people). The treatment of SMD in the European region has therefore become one of the main public health challenges in all and every one of the levels of medical care.2

This study has the objective of establishing an epidemiological profile based on the involuntarily hospitalized psychiatric population of Doctor Negrin University Hospital of Gran Canaria.

Material and methodsAn observational, descriptive, and retrospective study was undertaken of a sample of 380 patients admitted involuntarily to Doctor Negrín Hospital due to psychiatric disorder over a 2-year period (2019 and 2020), analyzing the following variables:

- •

Age

- •

Sex

- •

Marital status

- •

Work situation

- •

Fundamental diagnosis (according to the CIE classification system)

- •

Duration of admission

- •

Total number of previous admissions

- •

Drug use

- •

Acute agitation

- •

The need for mechanical restraint

- •

Abandonment of treatment prior to admission

- •

Acute self-harming behavior at the moment of admission

- •

The need for police intervention

An epidemiological study was carried out with descriptive analysis of the qualitative variables by calculating percentages, while quantitative variables were described in terms of their average and standard deviation. The association between 2 qualitative variables was determined by the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test when the former could not be applied. A result was considered to be statistically significant when P < .05.

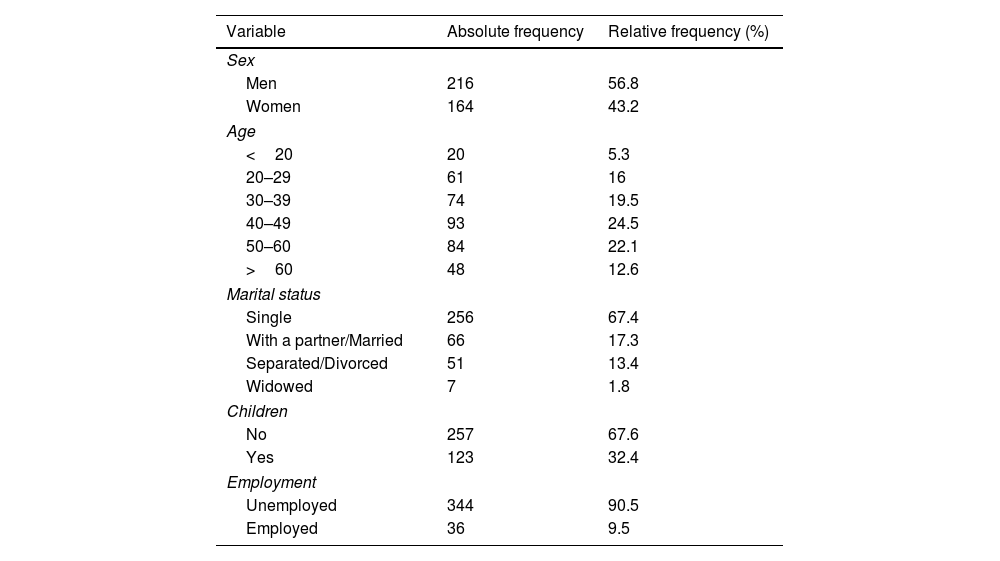

ResultsThe sociodemographic characteristics of the population studied are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the involuntarily admitted patients (n = 380).

| Variable | Absolute frequency | Relative frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 216 | 56.8 |

| Women | 164 | 43.2 |

| Age | ||

| <20 | 20 | 5.3 |

| 20–29 | 61 | 16 |

| 30–39 | 74 | 19.5 |

| 40–49 | 93 | 24.5 |

| 50–60 | 84 | 22.1 |

| >60 | 48 | 12.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 256 | 67.4 |

| With a partner/Married | 66 | 17.3 |

| Separated/Divorced | 51 | 13.4 |

| Widowed | 7 | 1.8 |

| Children | ||

| No | 257 | 67.6 |

| Yes | 123 | 32.4 |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 344 | 90.5 |

| Employed | 36 | 9.5 |

The majority are men (56.8%), with an average age of 43 years (15–80), and the subjects aged from 40 to 60 years are the most prevalent age groups in our sample, except for those subjects with an “organic disorder”, where patients aged over 60 years were the most prevalent. A statistically significant association was found (P < .001) between increasing age and this group of diseases. In terms of marital status, single patients predominated (67.4%), as did those without children (67.6%) and those who were unemployed (90.5%). No variations were found in the number of admissions depending on the months of the year.

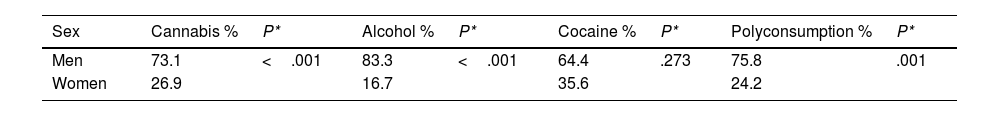

More than 50% of the patients in this study were categorized as non-consumers of drugs. Of the different substances consumed, cannabis was the most frequent (35%), followed by alcohol (13%) and cocaine (12%). 17% of the patients belonged to the “polyconsumption” phenotype which includes different combinations of substances. Men predominated as the consumers of all substances in a statistically significant way (P < .05) in all of the groups except for “cocaine consumers”. This is shown in Table 2.

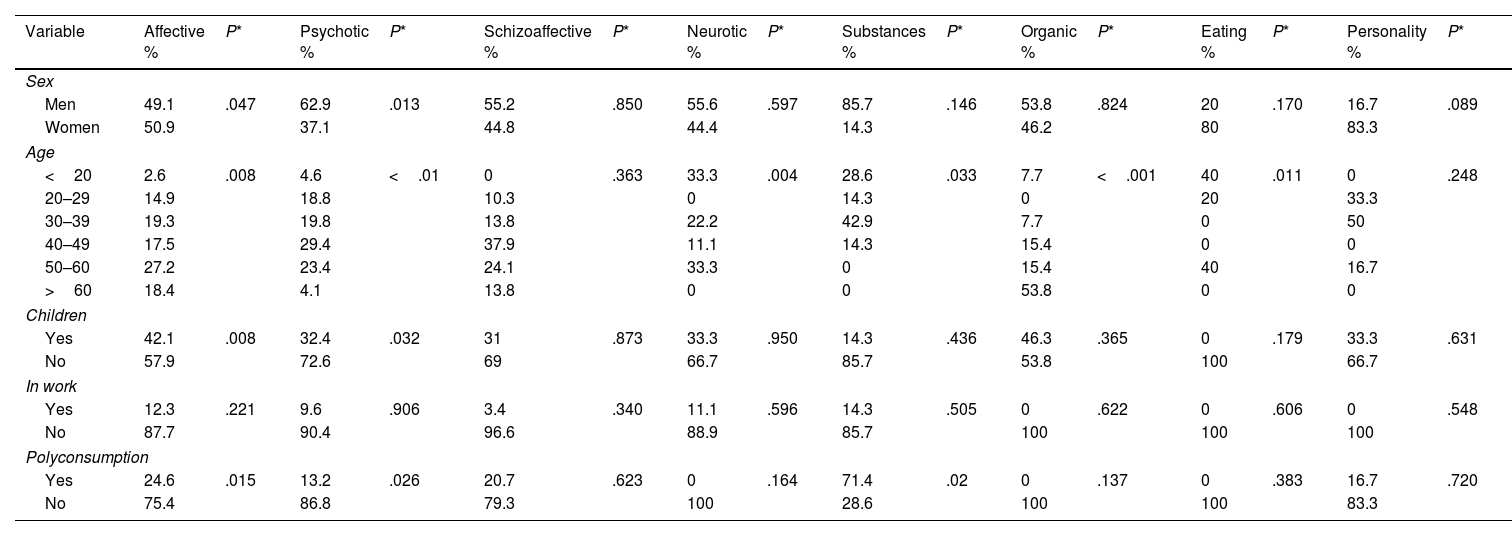

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the sample according to the type of disorder which led to admission. It should be pointed out that men form the majority in all of the diagnostic groups except for “eating disorders” and “personality disorders”, in which women account for the greater proportion of patients in the sample (80% and 83.3%, respectively).

Characteristics of the sample according to the type of disorder that led to admission.

| Variable | Affective % | P* | Psychotic % | P* | Schizoaffective % | P* | Neurotic % | P* | Substances % | P* | Organic % | P* | Eating % | P* | Personality % | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 49.1 | .047 | 62.9 | .013 | 55.2 | .850 | 55.6 | .597 | 85.7 | .146 | 53.8 | .824 | 20 | .170 | 16.7 | .089 |

| Women | 50.9 | 37.1 | 44.8 | 44.4 | 14.3 | 46.2 | 80 | 83.3 | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| <20 | 2.6 | .008 | 4.6 | <.01 | 0 | .363 | 33.3 | .004 | 28.6 | .033 | 7.7 | <.001 | 40 | .011 | 0 | .248 |

| 20–29 | 14.9 | 18.8 | 10.3 | 0 | 14.3 | 0 | 20 | 33.3 | ||||||||

| 30–39 | 19.3 | 19.8 | 13.8 | 22.2 | 42.9 | 7.7 | 0 | 50 | ||||||||

| 40–49 | 17.5 | 29.4 | 37.9 | 11.1 | 14.3 | 15.4 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| 50–60 | 27.2 | 23.4 | 24.1 | 33.3 | 0 | 15.4 | 40 | 16.7 | ||||||||

| >60 | 18.4 | 4.1 | 13.8 | 0 | 0 | 53.8 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Children | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 42.1 | .008 | 32.4 | .032 | 31 | .873 | 33.3 | .950 | 14.3 | .436 | 46.3 | .365 | 0 | .179 | 33.3 | .631 |

| No | 57.9 | 72.6 | 69 | 66.7 | 85.7 | 53.8 | 100 | 66.7 | ||||||||

| In work | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 12.3 | .221 | 9.6 | .906 | 3.4 | .340 | 11.1 | .596 | 14.3 | .505 | 0 | .622 | 0 | .606 | 0 | .548 |

| No | 87.7 | 90.4 | 96.6 | 88.9 | 85.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||

| Polyconsumption | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 24.6 | .015 | 13.2 | .026 | 20.7 | .623 | 0 | .164 | 71.4 | .02 | 0 | .137 | 0 | .383 | 16.7 | .720 |

| No | 75.4 | 86.8 | 79.3 | 100 | 28.6 | 100 | 100 | 83.3 | ||||||||

The tendency in all of the diagnostic groups was for the patients to be childless and unemployed. The “substance abuse disorder” group was the only one in which polyconsumption was evident, where it was present in 71.4% of cases. This result was statistically significant (P < .002).

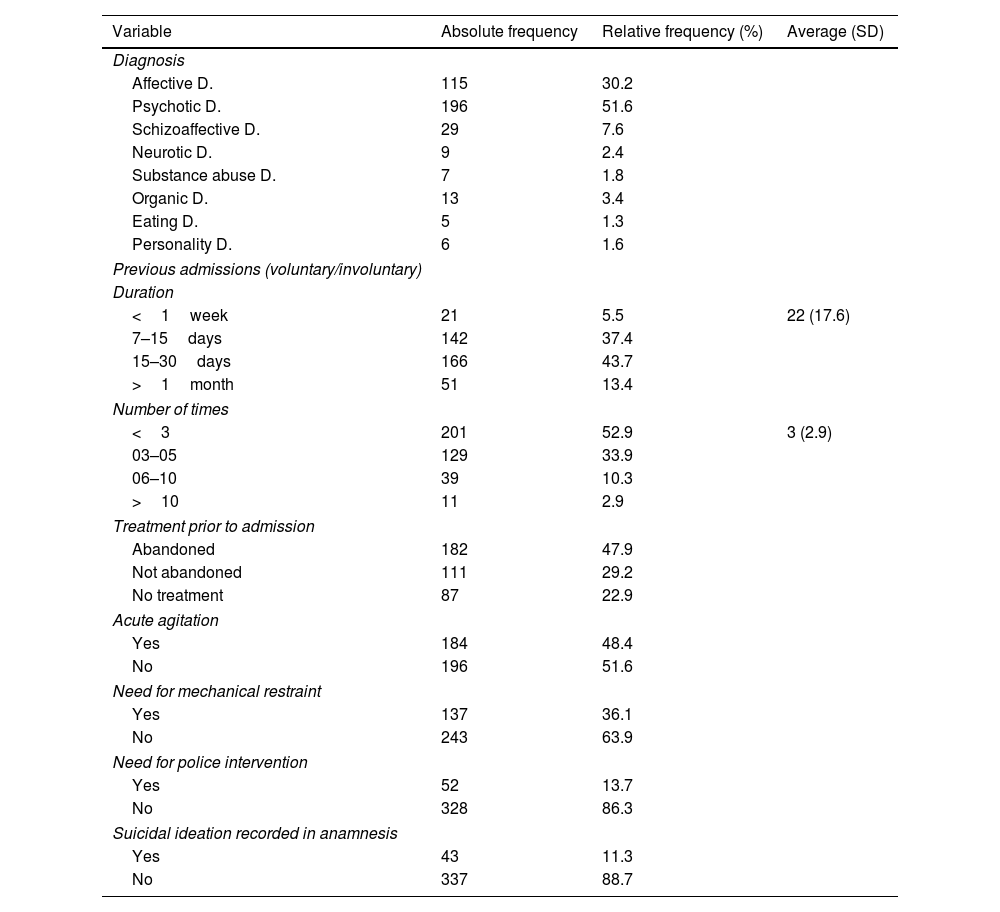

The clinical characteristics of the population studied are shown in Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of the patients admitted involuntarily (n=380).

| Variable | Absolute frequency | Relative frequency (%) | Average (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Affective D. | 115 | 30.2 | |

| Psychotic D. | 196 | 51.6 | |

| Schizoaffective D. | 29 | 7.6 | |

| Neurotic D. | 9 | 2.4 | |

| Substance abuse D. | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Organic D. | 13 | 3.4 | |

| Eating D. | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Personality D. | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Previous admissions (voluntary/involuntary) | |||

| Duration | |||

| <1week | 21 | 5.5 | 22 (17.6) |

| 7–15days | 142 | 37.4 | |

| 15–30days | 166 | 43.7 | |

| >1month | 51 | 13.4 | |

| Number of times | |||

| <3 | 201 | 52.9 | 3 (2.9) |

| 03–05 | 129 | 33.9 | |

| 06–10 | 39 | 10.3 | |

| >10 | 11 | 2.9 | |

| Treatment prior to admission | |||

| Abandoned | 182 | 47.9 | |

| Not abandoned | 111 | 29.2 | |

| No treatment | 87 | 22.9 | |

| Acute agitation | |||

| Yes | 184 | 48.4 | |

| No | 196 | 51.6 | |

| Need for mechanical restraint | |||

| Yes | 137 | 36.1 | |

| No | 243 | 63.9 | |

| Need for police intervention | |||

| Yes | 52 | 13.7 | |

| No | 328 | 86.3 | |

| Suicidal ideation recorded in anamnesis | |||

| Yes | 43 | 11.3 | |

| No | 337 | 88.7 | |

D: disorder.

The great majority of patients admitted involuntarily were in the psychotic disorders group (51.6%) or the affective disorders group (30.2%), while the patients who belonged to other groups were clearly in the minority.

The average length of involuntary admission was 22 days, and the largest group of patients were admitted for 15–30 days (43.7%). When the number of previous admissions was analyzed we found an average of 3 admissions before the one covered by our study. The majority of the patients had been admitted <3 times (52.9%).

Regarding treatment, approximately 50% of the patients had abandoned this before being hospitalized. Adding the patients without any prescribed treatment to this figure shows that 70% of the sample were not taking any type of medication, as opposed to 30% who were, according to the anamnesis with patients or their family.

48.4% of the patients had acute agitation at admission, while 51.6% did not. More than half of the patients, more specifically 64%, did not require mechanical restraint at the moment of admission, while 36% of the group did require this.

Only 11.3% of the patients had self-harming ideation, as opposed to 88.7% who did not. In 86% of cases, no police intervention was necessary at admission, as only 14% of the patients required this measure.

DiscussionThe findings are analyzed below:

Sex and ageBeing of male sex was found to be one of the factors involved in involuntary internment.1,4,7–11,15,16,19 The average age in our study was 43 years, and this datum is within the age range shown in the literature that was reviewed.8,21

Marital status and childrenThe great majority of the patients were single and had no children.1,4,7,8,14–17 This finding would express difficulties in relationships and a weak support system.1,18,21,22

Work situation90% of the patients were unemployed a the moment of admission.4,7–10,17,18,22 This result suggests severe mental disorder that was not properly treated as a major factor in their disability or early retirement.8 It also shows that many of them are victims of discrimination, as they are not allowed to take a job in society.21

DiagnosisThe main diagnosis was schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. This is in line with the research described in other papers,1,4,7–11,14–16,19 as disorders of this type benefit the most from acute treatment, as their clinical symptoms are more severe.15,18

Previous admissionsThis is a predictor of the need for a patient to be re-admitted in the future.1,2,4,7,14–18 The majority of the patients in our study had been admitted previously, which leads us to believe that involuntary admission occurs with patients who have a tendency to be admitted, so that they probably have more severe psychopathology.

Nevertheless, this study found that patients were admitted for an average of 22 days, which is longer than the corresponding figures in the literature that was reviewed. This may be because in some countries patients are discharged as soon as they cease to be dangerous, before their symptoms have resolved.4 This therefore suggests that a short hospitalization may not be sufficient to stabilize a patient.

Adherence to treatmentThis may be the risk factor that is the most closely associated with involuntary admission. More than 70% of the patients in this study were found to have abandoned treatment beforehand, or were not receiving medication of any kind. The figures relating to lack of adherence are extremely high in many studies, as well as in this one.1,4,8–11,14,17,19

Proper administration of treatment should be the priority to reduce the number of involuntary admissions per year.23 To achieve this, it is indispensable to have a comprehensive vision and understanding of the the patient's insight and their environment regarding the disease.24 Furthermore, it should be underlined that in previous studies depot formulations of antipsychotic drugs have been shown quite thoroughly to give rise to a lower rate of hospitalizations, so that this measure should also be taken into account.25

Drug abuseSubstance consumption has been associated with behavioral changes that may trigger involuntary admission.17,18,26 In our sample, more than 50% of the patients were categorized as “non-consumers”. This may be because this datum was obtained from clinical records. Additionally, a single patient may appear several times in the data if involuntary admissions occur during the study period; this is why we associate the low prevalence of consumption with the fact that the patients received detoxification/dishabituation therapy in previous admissions, so that no active consumption was recorded at the time of the current admission.

Acute agitation, the need for restraint, and police interventionThese 3 factors are all closely interlinked. Aggressive behavior often requires the intervention of the police during the internment process.21,26,28–30

However, in our sample, although half of the patients were notably agitated on arrival, there was far less need for mechanical restraints and police intervention was even less necessary, as it was required in only 13% of cases. The process used in this hospital stands out very positively in comparison with the existing literature, where a police presence is required in a significant number of cases.18

Self-harming behaviorPractically, 90% of patients showed no self-harming behavior at the moment of admission. In some studies, suicidal ideation is associated more with voluntary admissions than it is with involuntary ones.1,8,10 This may suggest that self-harming behavior is not a predictive factor for the need for the involuntary admission of a psychiatric patient.

ConclusionThe patient profile associated with involuntary admission in our department corresponds to that of a male in the fourth decade of life, single, without children, and unemployed, with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or a major affective disorder, who has very probably abandoned treatment.

In clinical practice, it is recommended that patients who fulfill the above profile should be especially monitored, to minimize involuntary admissions.

LimitationsThe chief limitation of this study arises from its design. Exclusively using information contained in clinical records and the quality of the same hinders the detection of certain variables such as “drug abuse” or “the need for mechanical restraint”, as well as the “period during which previous admissions occurred”; only the main ICD diagnosis shown was included, excluding comorbidity.

As it was not possible to compare groups in this study, it is solely epidemiological. We are therefore currently unable to specify whether the variables studied are predictive or not of involuntary admission. Although the discussion aims to propose measures that improve these variables, it is possible that they are associated with any type of internment in a psychiatric hospitalization unit and are not specific to involuntary admission. It would therefore be of interest to determine which factors are associated with involuntary admission, to explain why the capacity to give consent is reduced or to improve the suitability of the type of internment in each specific case.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Hernández N, Martínez Grimal M, Cabrera Velázquez C, Rodríguez Medina R, Sánchez Villegas A, Hernández Fleta JL. Epidemiological profile of involuntary admission in the Psychiatry Service of the University Hospital of Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2023.04.001.