To determine whether there is a seasonal relationship in the incidence and in-hospital mortality of patients with hip fracture.

Patients and methodsLongitudinal descriptive study of cases that included 1104 patients older than 64 years admitted for fracture of the proximal extremity of the femur in the Hospital HCU Virgen de la Victoria during a period of 30 months The epidemiological characteristics of the patients were recorded and the monthly incidence of fractures was related with the month of the year in which it occurred, as well as with the meteorological conditions, temperature and rainfall.

ResultsThe study population comprised a total of 1104 patients, with a greater proportion of women (75.1%). The average age was 82.3 years. A tendency towards an increased incidence of these fractures was found. The in-hospital annual mortality rate was 2.97%, higher for men and in the age group over 84 years. Seasonality was found in terms of the incidence of fractures above the average in the month of October and below this in the month of February. On the other hand, mortality was lower than the average in the month of March and higher in August. In both, a low correlation with temperature and rainfall was found.

ConclusionsThe seasonal distribution of hip fractures presented an increase over the average in the month of October and a decrease in February. Mortality increased over the average in the month of August and decreased in March.

Determinar si existe relación estacional en la incidencia y en la mortalidad intrahospitalaria de los pacientes con fractura de cadera.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio descriptivo longitudinal de casos que incluye 1.104 pacientes mayores de 64 años ingresados por fractura de la extremidad proximal del fémur en el Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria de Málaga durante un periodo de 30 meses. Se registraron las características epidemiológicas de los pacientes y se relacionó la incidencia mensual de fracturas con el mes del año en que ocurre, y con las condiciones meteorológicas: temperatura y pluviometría.

ResultadosLa población estudiada la componen un total de 1.104 pacientes, con mayor proporción de mujeres (75,1%). La edad media fue de 82,3 años. Se ha hallado una tendencia al aumento de la incidencia de estas fracturas. La tasa anual de mortalidad durante la estancia hospitalaria fue del 2,97%, siendo mayor entre hombres y en el grupo de edad de más de 84 años. Se ha encontrado una estacionalidad en cuanto a la aparición de fracturas por encima de la media en el mes de octubre y por debajo de esta en el mes de febrero. Por su parte, la mortalidad es inferior a la media en el mes de marzo y superior en el mes de agosto. En ambas se ha encontrado una correlación baja con temperatura y pluviometría.

ConclusionesLa distribución estacional de las fracturas de cadera presenta aumento sobre la media en octubre y disminución en febrero La mortalidad se eleva sobre la media en agosto y disminuye en marzo.

Proximal femoral fractures include those of the cervical and trochanteric regions. This type of fracture is related to bone fragility and occurs to a greater extent in ages over 65, with the average age being 82 years and the female sex being predominant at a ratio of 3:1. It has been calculated that incidence rates are 517 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year.1 Furthermore, this is a pathology which is expected to progressively increase with the ageing of the population. However it has been predicted that there will be a fall in rates for women under 80 years of age, and an increase in that of both sexes over 85 years of age.2

Hospital mortality for these patients is 5% and it is higher for males, at a ratio of 2:1. This mortality is linked to complications which are essentially respiratory, ischaemic cardiopathy and heart failure.3 Mortality is also linked to a more advanced age and the cold winter months. Additionally, these patients usually present with a longer hospital stay, of between 16 and 19 days. The risk of mortality in patients diagnosed with these injuries during the first year is 24%,4 with this risk being three times as high as that of other people in the same age group.5

Seasonal distribution of these fractures is not uniform. A higher incidence has been reported in winter (26.8%) and lower in summer (23.4%). For the Community of Andalusia, this distribution is 27.6% and 23.4%, respectively. However, this is not always so: in Cantabria and Aragón the highest incidence occurs in spring. In Navarre, on the contrary, there is no seasonal variability. The same occurs with mortality, with in-hospital mortality being recorded as 4.6% in summer and 5.6% in winter.1

Study objectives- •

Study the seasonal distribution of hip fractures in patients over 64 years of age in the HCU Virgen de la Victoria (HCUVV) dependent area for 30 months, during the period between July 2013 and December 2015.

- •

Find out the in-hospital mortality of these patients.

Longitudinal descriptive study of case series.

Sample selectionThe target sample were people over 64 years of age with proximal femoral fractures attended by the traumatology and orthopaedics department of the HCUVV during the period between June 2013 and December 2015. An exclusion criterion was established for pathological fractures, which are those occurring as a result of tumour or pseudotumour lesion.

Cases were taken from the hospital database of those fractures included in the international classification of CIE-9-MC diseases and injuries as femoral fracture. Trochanteric fractures included those classified as closed intertrochanteric line fractures, greater and lesser trochanteric fractures and non specified (CIE-9-MC 820.20 and 820.21) fractures. Cervical femoral fractures included those classified as closed intracapsular line fractures, femoral neck base fractures or cervical trochanteric section, subcapital section and the non specified part of the neck of the closed femur fractures (CIE-9-MC 820.00, 820.03, 820.09 and 820.89).

A total of 1104 patients met with these criteria. 45.2% were classified as intracapsular fractures and 54.8% as extracapsular.

In the selected sample the following were recorded: medical file number, age, sex, date of admittance, hospital stay and cases of death during stay. Monthly mean temperature and monthly mean rainfall data were collected for studying seasonability.

Variable age was stratified into groups aged 65–74, 75–84 and >84 years.

In-hospital mortality was considered as that which occurred during hospital stay and prior to patient discharge.

The monthly mean temperature was collected in Celsius and the level of mean rainfall in cc/m3. These data were obtained from the monthly summary of the State Agency of Meteorology (AEMET).6

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis, quantitative variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation and qualitative data as absolute frequency and percentages.

For dichotomic variable contrast the exact Fisher test was used and for continuous variables the Student's t-test was used.

To compare the variation of the incidence of both types of fracture with age the sample was stratified into intervals of 65–74, 75–84 and >84 years of age and the χ2 test was used.

For comparability of mortality between the groups analysed, contingency tables were used to calculate the relative risk expressed as a value and confidence interval.

To establish the strength of association between qualitative variables lineal regression analysis with expression of R2 was used.

Differences with a p value of .5 were considered to be statistically significant.

The variability of area was calculated using the additive analytical study for mobile means with calculation of seasonality and tendency.

Tables for population characteristics and dispersion and line graphs were created to establish the evolution of data throughout the series.

Data were analysed using the statistical package SPSS 23.0 and the GraphPad QuickCalcs software.7

ResultsPatient distributionA total of 30 months were submitted for analysis, between July 2013 and December 2015, inclusive of both. The population studied comprised 1104 patients of whom 275 were men (24.9%) and 829 were women (75.1%), with an incidence rate of 441.6patients/per year. The mean global age was 82.3 years (SD 7.37). For men the mean age was 81.54 years (SD 7.75) and for women 82.5 years (SD 7.23).

Regarding age groups, the most numerous was that of patients aged between 75 and 84 years: 476 (43.1%); 447 (40.5%) were aged 85 or above and 181 (16.4%) were aged between 65 and 74.

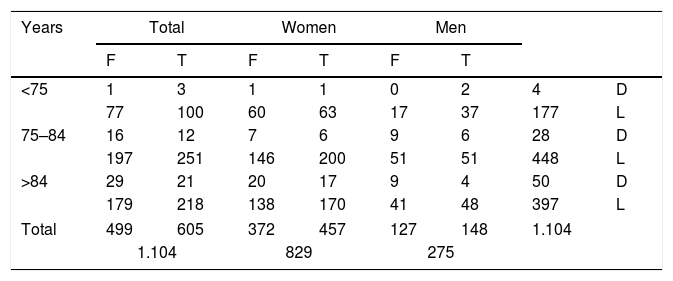

Of the 1104 patients included in the study admitted to hospital due to PFF, 605 (54.8%) presented with a trochanteric fracture and 499 patients (45.2%) presented with a femoral neck fracture. The stratified frequency distribution by gender, fracture type, age group and whether the patient had died or not is reflected in Table 1.

Sample distribution.

| Years | Total | Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | T | F | T | F | T | |||

| <75 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | D |

| 77 | 100 | 60 | 63 | 17 | 37 | 177 | L | |

| 75–84 | 16 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 28 | D |

| 197 | 251 | 146 | 200 | 51 | 51 | 448 | L | |

| >84 | 29 | 21 | 20 | 17 | 9 | 4 | 50 | D |

| 179 | 218 | 138 | 170 | 41 | 48 | 397 | L | |

| Total | 499 | 605 | 372 | 457 | 127 | 148 | 1.104 | |

| 1.104 | 829 | 275 | ||||||

F: femoral neck fracture; D: deceased; T: trochanteric fracture; L: living.

Mean hospital stay was 11.4 days (range 1–88): 11.3 for men and 12.3 for women.

In-hospital mortalityThe absolute frequencies referring to mortality are contained in Table 1.

During hospital stay a total of 82 deaths occurred, which is equivalent to an annual recorded mortality rate of 2.97%, being an annual 5% of men and 2.5% of women. This difference was found to be statistically significant between the sexes for mortality: 30 among the men and 52 among the women (RR: 1.74, CI: 1.13–2.67). According to the diagnosis, there was no difference in mortality: the fractures of the cervical region made up a total of 46 affected in the neck area and 36 in the trochanteric area (RR: 1.05; CI: 0.69–1.60). By gender, when stratifying by fracture type no significant difference was to be found in mortality when those found in males were compared (RR: 0.57; CI: 0.28–1.14) to those found in women (RR: 0.70; CI: 0.41–1.18).

Comparison between groups found a statistically significant mortality when they compared patients aged between 65 and 74 with those over 84 (RR: 0.20; CI: 0.08–.54) and the group aged between 75 and 84 with those patients aged 85 or over (RR: 0.53; IC: 0.34–0.82), but not when comparing the younger groups (RR: 0.38; CI: 0.13–1.05).

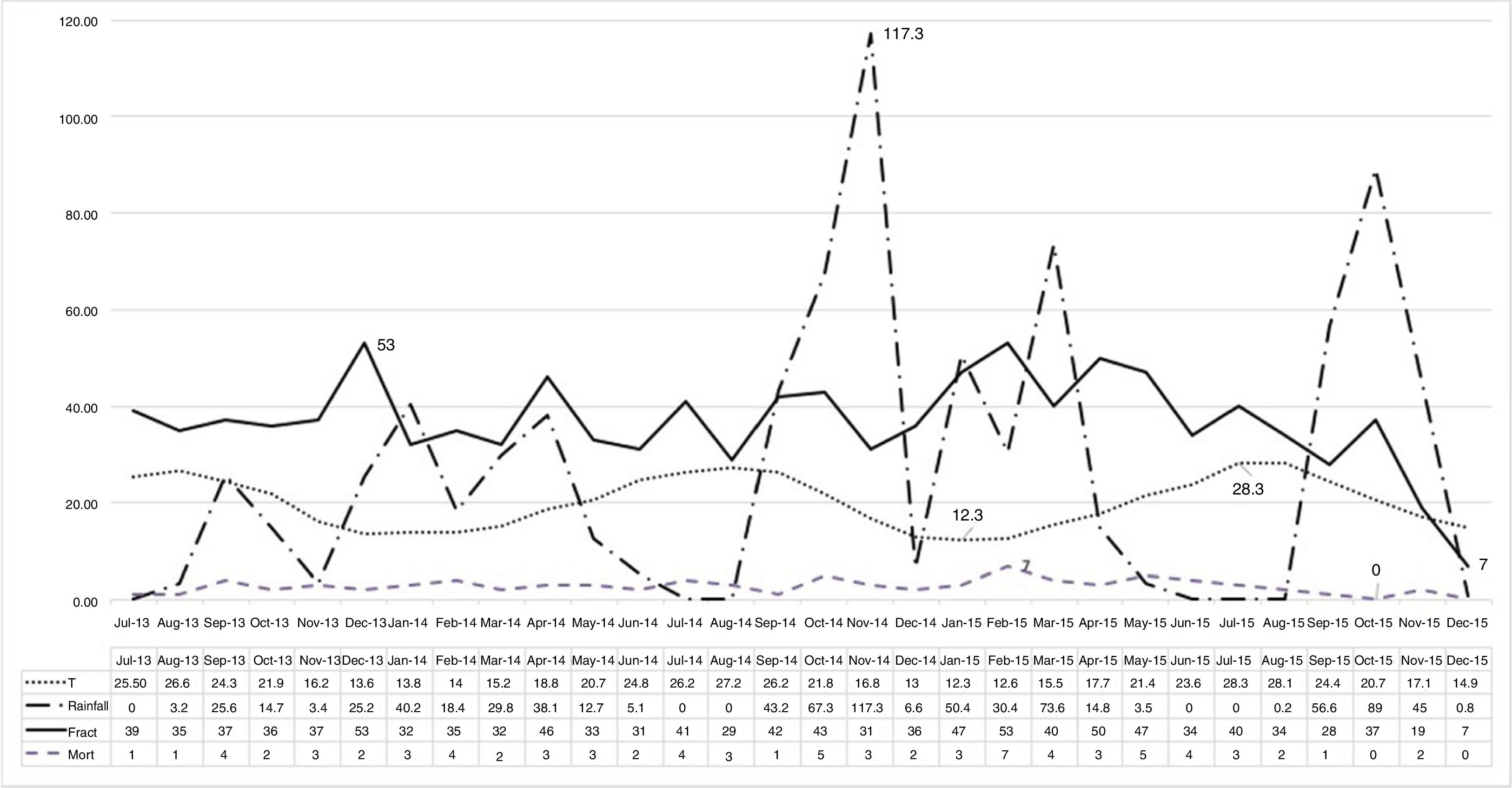

SeasonalityFig. 1 contains the data corresponding to the months studied with expression of fracture frequency, occurrence of mortality and figures reaching both mean monthly temperatures and rainfall.

We may appreciate seasonality in the data analysed for the incidence of hip fractures, according to which over the annual mean, the sharpest drop occurs in February with 7.1 cases and the highest rise occurs in October with 9.8 cases.

When the influence of seasonality in death is studied, we may observe that March is the month where there is the most significant drop, with −2.17 cases, whilst August has the highest increase over the mean at 2.16.

However, in contrasting statistics between the incidence of fracture and recorded temperature or rainfall, a low correlation is found (R2=.006 for temperature and R2=.002 for rainfall).

TendencyIn the collected data a tendency may be observed (centred moving tendencies calculated for the additive method in time) on the increase in hip fractures rates (R2=.67).

DiscussionOur study includes a total of 1104 patients over 64 who were cared for in HCUVV for 30 months, with an average admittance of 441.6 patients per year. There was a higher rate of females (75.1%)1,8 and an average age of 82.3 years, similar to that found in other series.9,10 In our sample the most common age group was between 75 and 84 years.

A tendency for the annual rate of these fractures to increase was found, which has been extensively reported in the literature, albeit irregularly, with the age group over 85 years of age being the one with the highest rate of increase.11 In our study the age group between 75 and 84 is the one with the highest number of patients, but with little difference to those over 84.

The in-hospital mortality rate of our patients was situated at an annual 2.97%, with different figures for men (5%) and women (2.5%), which situates it below the figures found in the literature, that oscillate between 3.6% and 6.2%.10,12 Mortality showed a statistically significant difference with a higher risk for men compared to women, and this coincides with other publications.10 With regards to the mortality by age group, similar contrasts have also been found to those published, with the highest risk group being that over 84 compared to patients who were younger.13

Previous studies reported seasonality analysed according to meteorological seasons with focus on higher observation in the Winter months (26.8%) and lower in summer (23.4%).1 Our study was made by analysing fracture rates monthly, although during a lower observation period (30 months). We do not coincide with them, finding an inverse seasonality, with greater rates in an autumn month (October), with a mean increase of 9.8 cases, and a lower observation in a winter month (February), with a drop below the mean of 7.1. This same study coincides with all autonomous communities in presenting a higher fracture rate during winter. In contrast, in other publications on the Spanish population no seasonality was found at all.14 In other populations with different meteorological conditions reference to this seasonality was also made, and was related to situations of vitamin D deficiency.15 Despite the conviction that a sufficient amount of sunshine seems to immunise against vitamin D deficiency, it has been proven that in our environment this is not borne out by reality and this deficiency has a high prevalence which may affect almost the whole population, depending on the age group.16

Another factor which has been linked to seasonality is the presence of slippery surfaces due to ice or rain.17 In our population, although the recorded rainfall and temperature are not usually high volumes or extreme changes, none of the levels reached explain the rate of fractures (R2=.002 and R2=.006, respectively). These same values serve to contrast the explanations that high temperatures in the summer months could lead to episodes of overheating and dehydration,18 as the greatest deviation from the mean occurs in the month of October, when temperatures are more moderate.

Study limitationsDespite a high number of patients analysed, the main limitation of this study was the relatively short period of analysis, of 30 months. It was however possible to establish seasonality and tendency, which should be confirmed by longer periods of time.

Conclusions- •

Seasonal distribution of hip fracture in the Hospital HCUVV shows a high raise over the mean during the month of October and a greater fall in the months of February.

- •

Mortality during hospital stay is lower than those communicated previously and was not influenced by seasonality.

Level of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Zamora-Navas P, Esteban-Peña M. Estacionalidad en incidencia y mortalidad en las fracturas de cadera. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:132–137.