Since the spread of the first cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection much progress has been made in understanding the disease process. However, we are still facing the complications of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Multiple sequelae may appear as a consequence of acute infection. This set of entities called post-COVID-19 syndrome involves a wide variety of new, recurrent or persistent symptoms grouped together as a consequence of the acute disease process. One of those that has attracted the most attention is the liver and bile duct involvement called post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy. This is characterized by elevation of liver markers such as alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin and transaminases as well as alterations in the bile ducts in imaging studies. Thus, a narrative review of the cases reported until the end of 2021 was carried out. From the findings found, we concluded that patients who have had COVID-19 or during the process have required hospitalization should remain under follow-up for at least 6 months by a multidisciplinary team.

Desde la propagación de los primeros casos del síndrome respiratorio agudo severo por coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) se ha avanzado mucho en la comprensión del proceso de enfermedad. Sin embargo, todavía nos enfrentamos a las complicaciones del coronavirus 19 (COVID-19). Se han reportado múltiples secuelas como consecuencia de la infección aguda. Este conjunto, denominado síndrome post-COVID-19, involucra una amplia variedad de síntomas nuevos, recurrentes o persistentes agrupados como consecuencia del proceso agudo de la enfermedad. Una de las que más ha llamado la atención es la afectación hepática y de vías biliares denominada colangiopatía post-COVID-19. Esta se caracteriza por elevación de marcadores hepáticos tales como fosfatasa alcalina, bilirrubina y transaminasas, así como alteraciones en las vías biliares en los estudios de imagen. Así, se realizó una revisión narrativa de los casos reportados hasta finales de 2021. De los hallazgos encontrados concluimos que los pacientes que han tenido COVID-19 o que han requerido hospitalización deben permanecer en seguimiento durante al menos 6 meses por parte de un equipo multidisciplinario.

In late December 2019, some cases of severe atypical pneumonia began to be reported in the city of Wuhan, China1 which would later be denominated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This infection is caused by a new family member from coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).2 The spread throughout the countries occurred imminently and rapidly from the beginning of the first cases until it became a global pandemic with dangerous consequences for global health. Despite the measures taken by many countries to curb infections it has now produced more than 262 million infections and more than 5 million deaths worldwide.3 With scientific progress it has been possible to develop vaccines and drugs against the disease, however uncertainty and worry remains due to the appearance of new viral variants, reinfections, duration of vaccine protection and countries in which second, third and fourth waves. Currently, several countries have reported the increase in cases of spread and infection by COVID-19, so the health alert is still maintained worldwide.

Patients with COVID-19 can present as asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe and critical forms. Most of the patients are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms.4 The most common clinical findings are fever, cough, sore throat and fatigue, with some altered laboratory findings such as increased serum ferritin, D-dimer and C-reactive protein.5 A small proportion of patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized for moderate and severe stages mainly secondary to respiratory failure which can be fatal in vulnerable individuals despite getting mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit.

SARS-COV-2 virus binds through its spike protein located on its outer surface to the angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor 2 (ACE2), which is widely distributed in lung alveolar epithelial cells, small intestinal enterocytes, arterial and venous endothelial cells, and arterial smooth muscle cells.6 These findings provide evidence on the pathways of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and on the pathogenesis of the main manifestations of the disease. The liver and the bile duct, vital human organs, also expresses the ACE2 receptor. However, the number of receptors expressed is higher in the cholangiocytes than in hepatocytes. This may be the reason that explains the liver injury and why is clinically oriented more to a late complication of the acute infection than a side effect of the medication or another clinical explanation. A few cases have been reported in the world data in which this damage may extend beyond the acute infection time.7 This syndrome called post COVID-19 cholangiopathy, is characterized by abnormal liver tests mainly elevations of transaminases, serum alkaline phosphatase, bilirubins and accompanied by imaging findings of biliary tract injury.8,9 It appears in patients recovering from severe COVID-19 and constitutes a potential cause of long-term liver morbidity.

Understanding post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy may help clarify the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the liver in order to prevent some clinical events after discharging and take the actions to prevent to increase morbidity in recovering patients. This article reviews the definition, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy.

Definition of post-COVID cholangiopathyPost-COVID-19 cholangiopathy is defined as an extrapulmonary complication of COVID-19 disease, characterized by a marked elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase, accompanied by evidence of bile duct injury on imaging, i.e., the injury occurs at the level of the bile ducts; it has also been referred to as post-COVID-19 sclerosing cholangitis.10 It appears in patients recovering from severe COVID-19, in the convalescence period and currently configures a new entity that requires further studies.

PathophysiologyEntry of the SARS-CoV-2 virus into host cells of the body is initiated by the binding of the virus particle through the outer surface glycoprotein peaks to the host surface receptor. The RBD domain of the S1 region of the S protein interacts with the host ACE2 receptor.11 The ACE2 receptor is present on the cell membranes of multiple organs, including the lungs, arteries, kidney, heart and intestines.12 Cell types and organs at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection within the human body can be predicted based on cells expressing the ECA2 gene.

In relation to the liver, it has been reported that cholangiocytes have the highest expressivity compared to hepatocytes, and at this level there would be a cytopathic and immunological effect that would result in cholangiopathy.13 and at this level there would be a cytopathic and immunological effect that would result in cholangiopathy.

One of the pathophysiological theories of this disease is that there is a combination of bile duct ischemia (ischemic cholangiopathy) and toxic bile. In relation to ischemia the biliary epithelium is more susceptible because it is only irrigated through the hepatic arteries in comparison with the hepatocytes that have a double supply of oxygenated blood. Furthermore, the changes at the level of the composition of the bile (toxic bile) generates together the necrosis of the cholangiocytes and the formation of cylinders. Toxic bile causes an alteration in the protective mechanisms; consequently, the detergent properties of hydrophobic bile acids injure the lipid membrane of the cholangiocytes. It is known that one of the most important mechanisms is the secretion of phospholipids at hepatocellular level, which favors the formation of protective mixed micelles together with bile acids. Also, bicarbonate secretion at the biliary level results in the formation of a protective alkaline film on the apical membrane of the cholangiocytes, contributing as part of the defense strategy. There is a very marked balance between bile acids and protective mechanisms; this is of utmost importance to maintain the bile duct epithelium intact. Because of all of the above, an imbalance will result in severe damage to the biliary epithelium and the development of cholangiopathy.14

DiagnosisCholangiopathy is considered a late syndrome of COVID-19 disease. Although there is no clear clinical picture, there are clinical manifestations, laboratory and imaging findings that bring us closer to the diagnosis of this complication.

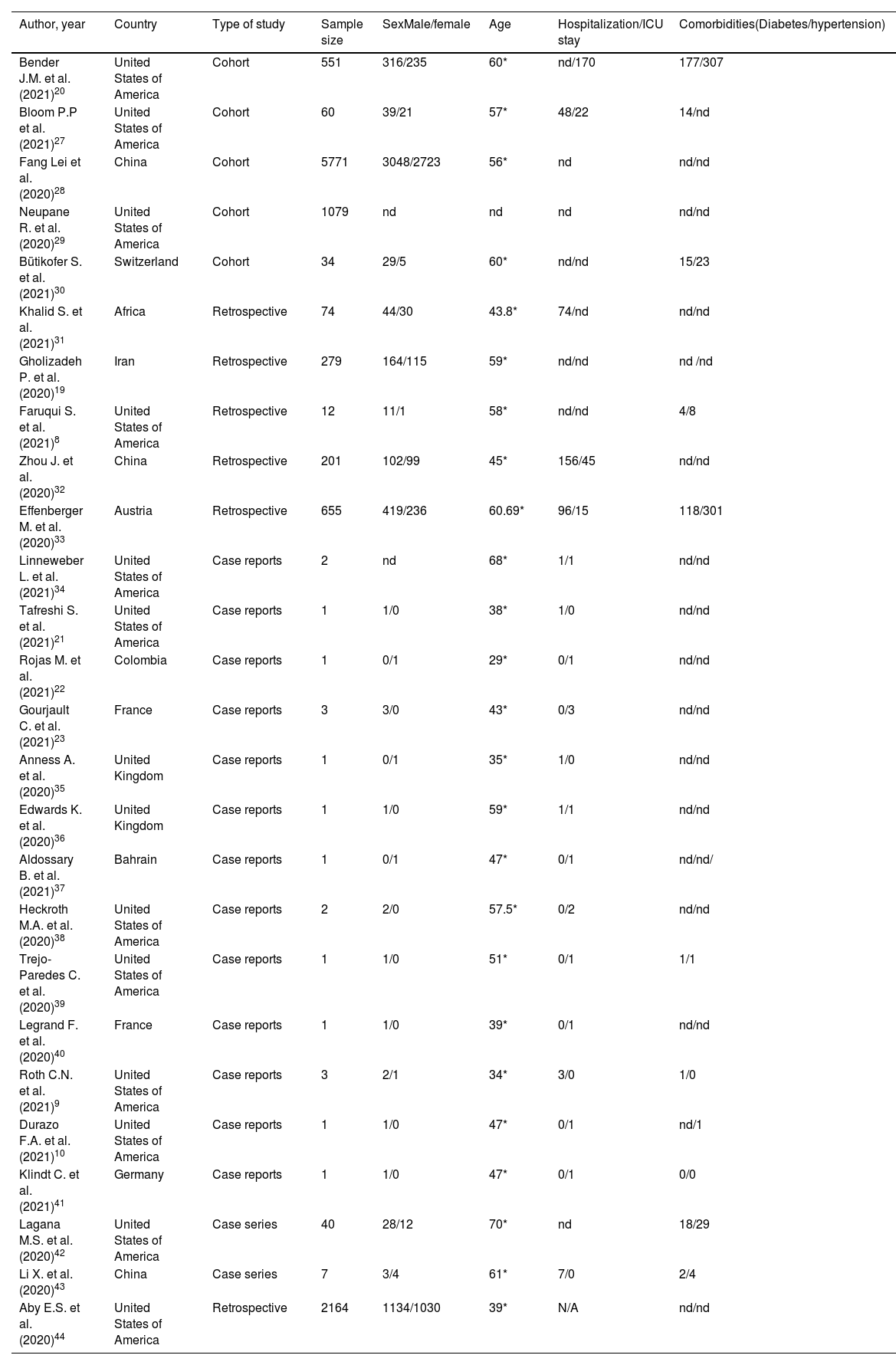

Clinical featuresFrom the clinical point of view, the incidence of liver injury is associated with severe cases of COVID-19 (Table 1).15 Despite the fact that the clinical impact at the hepatic level is not very noticeable16 in a study of 204 patients with COVID-19, it was concluded that those with digestive symptoms were more likely to have hepatocellular damage.17

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Country | Type of study | Sample size | SexMale/female | Age | Hospitalization/ICU stay | Comorbidities(Diabetes/hypertension) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bender J.M. et al. (2021)20 | United States of America | Cohort | 551 | 316/235 | 60* | nd/170 | 177/307 |

| Bloom P.P et al. (2021)27 | United States of America | Cohort | 60 | 39/21 | 57* | 48/22 | 14/nd |

| Fang Lei et al. (2020)28 | China | Cohort | 5771 | 3048/2723 | 56* | nd | nd/nd |

| Neupane R. et al. (2020)29 | United States of America | Cohort | 1079 | nd | nd | nd | nd/nd |

| Bütikofer S. et al. (2021)30 | Switzerland | Cohort | 34 | 29/5 | 60* | nd/nd | 15/23 |

| Khalid S. et al. (2021)31 | Africa | Retrospective | 74 | 44/30 | 43.8* | 74/nd | nd/nd |

| Gholizadeh P. et al. (2020)19 | Iran | Retrospective | 279 | 164/115 | 59* | nd/nd | nd /nd |

| Faruqui S. et al. (2021)8 | United States of America | Retrospective | 12 | 11/1 | 58* | nd/nd | 4/8 |

| Zhou J. et al. (2020)32 | China | Retrospective | 201 | 102/99 | 45* | 156/45 | nd/nd |

| Effenberger M. et al. (2020)33 | Austria | Retrospective | 655 | 419/236 | 60.69* | 96/15 | 118/301 |

| Linneweber L. et al. (2021)34 | United States of America | Case reports | 2 | nd | 68* | 1/1 | nd/nd |

| Tafreshi S. et al. (2021)21 | United States of America | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 38* | 1/0 | nd/nd |

| Rojas M. et al. (2021)22 | Colombia | Case reports | 1 | 0/1 | 29* | 0/1 | nd/nd |

| Gourjault C. et al. (2021)23 | France | Case reports | 3 | 3/0 | 43* | 0/3 | nd/nd |

| Anness A. et al. (2020)35 | United Kingdom | Case reports | 1 | 0/1 | 35* | 1/0 | nd/nd |

| Edwards K. et al. (2020)36 | United Kingdom | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 59* | 1/1 | nd/nd |

| Aldossary B. et al. (2021)37 | Bahrain | Case reports | 1 | 0/1 | 47* | 0/1 | nd/nd/ |

| Heckroth M.A. et al. (2020)38 | United States of America | Case reports | 2 | 2/0 | 57.5* | 0/2 | nd/nd |

| Trejo-Paredes C. et al. (2020)39 | United States of America | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 51* | 0/1 | 1/1 |

| Legrand F. et al. (2020)40 | France | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 39* | 0/1 | nd/nd |

| Roth C.N. et al. (2021)9 | United States of America | Case reports | 3 | 2/1 | 34* | 3/0 | 1/0 |

| Durazo F.A. et al. (2021)10 | United States of America | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 47* | 0/1 | nd/1 |

| Klindt C. et al. (2021)41 | Germany | Case reports | 1 | 1/0 | 47* | 0/1 | 0/0 |

| Lagana M.S. et al. (2020)42 | United States of America | Case series | 40 | 28/12 | 70* | nd | 18/29 |

| Li X. et al. (2020)43 | China | Case series | 7 | 3/4 | 61* | 7/0 | 2/4 |

| Aby E.S. et al. (2020)44 | United States of America | Retrospective | 2164 | 1134/1030 | 39* | N/A | nd/nd |

NA: no data.

The main manifestations found in a post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy is marked cholestasis and jaundice following recovery from pulmonary and renal manifestations.10 Although, in several patients cholangiopathy develops during the infection most of them occur during the convalescence period or after it, just in this period patients with biliary lesions and liver failure have been reported.18

A case series conducted by Faruqui et al.,8 in the USA reported that the average time from diagnosis of COVID-19 to diagnosis of cholangiopathy was 118 days, i.e., being considered a late complication of severe COVID-19 with the potential for progressive biliary injury and liver failure.

Other outstanding characteristics in the analysis of 26 studies shown in Table 1 are that it has been reported mainly in the male sex; in addition, it was found that the mean age at which it occurs is 50.5 years; of the 10,946 patients studied it was reported that at least 263 of them became hospitalized in the ICU. Of all patients at least 3% had diabetes mellitus and 6% had hypertension.

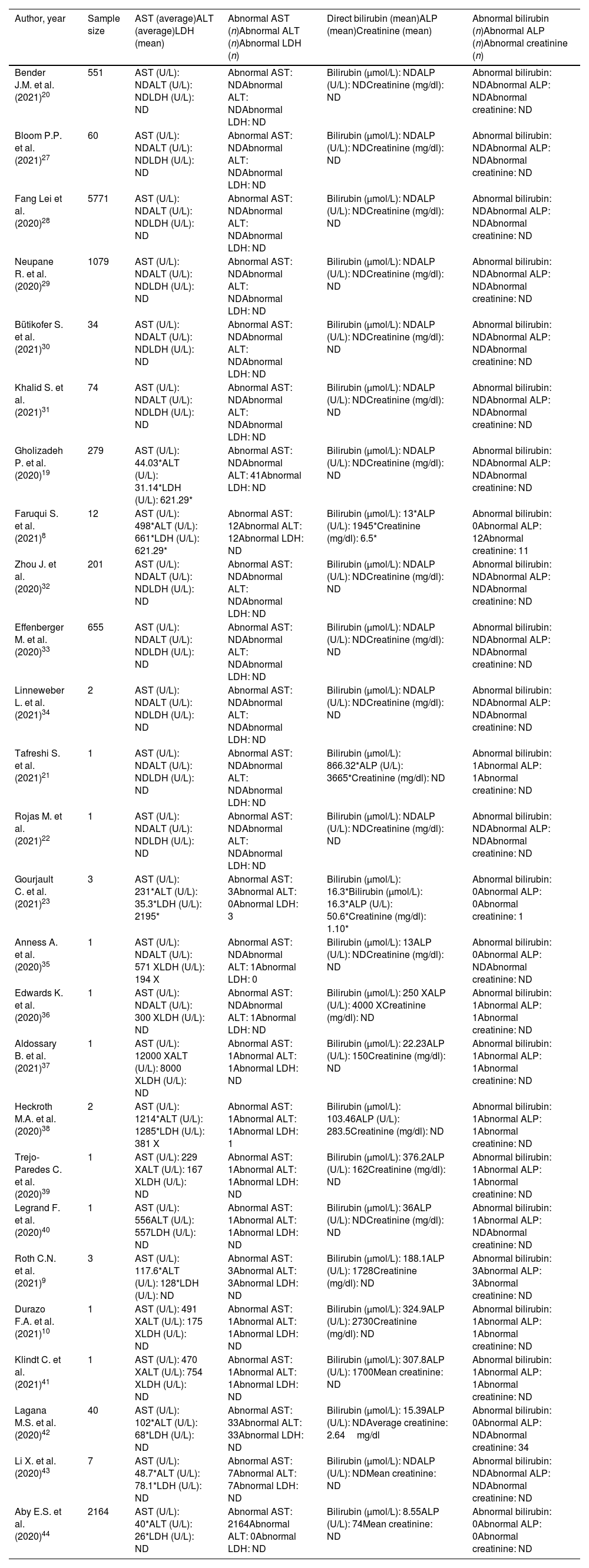

BiochemistryPost-COVID-19 cholangiopathy is often associated with altered liver tests, as shown in Table 2, where 26 studies were analyzed. The reviewed studies shown serum elevations of hepatic markers such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (n=13), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (n=12),8–10,21–27,29,30 aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (n=12),8–10,19–28 lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (n=5),8,19,20,22,29 direct bilirubin (DBIL) (n=9),9,10,21–25,30,31 alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (n=9),8–10,21–23,25,30,31 and serum creatinine (sCr) (n=3).8,20,26. A few studies analyzed shown minimal changes in hepatic values. Roth et al.,9 reported normal or slightly elevated liver biochemistry in 3 patients during admission at the hospital; ALP values of 81U/L, 80U/L and 163U/L; ALT values of 34U/L; 52U/L, U/L, 20U/L and AST values of 30U/L; 55U/L; 24U/L respectively. During subsequent evaluations, all the patients from this study developed a well-marked cholestasis associated with jaundice that persisted after recovery. ALP values increased to 1911U/L, 2018U/L,1256U/L. ALT values 172U/L, 132U/L, 80U/L and AST in 112U/L, 151U/L, 90U/L respectively (Table 2).

Alterations in hepatic biochemical markers in patients with post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy.

| Author, year | Sample size | AST (average)ALT (average)LDH (mean) | Abnormal AST (n)Abnormal ALT (n)Abnormal LDH (n) | Direct bilirubin (mean)ALP (mean)Creatinine (mean) | Abnormal bilirubin (n)Abnormal ALP (n)Abnormal creatinine (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bender J.M. et al. (2021)20 | 551 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Bloom P.P. et al. (2021)27 | 60 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Fang Lei et al. (2020)28 | 5771 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Neupane R. et al. (2020)29 | 1079 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Bütikofer S. et al. (2021)30 | 34 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Khalid S. et al. (2021)31 | 74 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Gholizadeh P. et al. (2020)19 | 279 | AST (U/L): 44.03*ALT (U/L): 31.14*LDH (U/L): 621.29* | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: 41Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Faruqui S. et al. (2021)8 | 12 | AST (U/L): 498*ALT (U/L): 661*LDH (U/L): 621.29* | Abnormal AST: 12Abnormal ALT: 12Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 13*ALP (U/L): 1945*Creatinine (mg/dl): 6.5* | Abnormal bilirubin: 0Abnormal ALP: 12Abnormal creatinine: 11 |

| Zhou J. et al. (2020)32 | 201 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Effenberger M. et al. (2020)33 | 655 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Linneweber L. et al. (2021)34 | 2 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Tafreshi S. et al. (2021)21 | 1 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 866.32*ALP (U/L): 3665*Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Rojas M. et al. (2021)22 | 1 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): NDLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: NDAbnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Gourjault C. et al. (2021)23 | 3 | AST (U/L): 231*ALT (U/L): 35.3*LDH (U/L): 2195* | Abnormal AST: 3Abnormal ALT: 0Abnormal LDH: 3 | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 16.3*Bilirubin (μmol/L): 16.3*ALP (U/L): 50.6*Creatinine (mg/dl): 1.10* | Abnormal bilirubin: 0Abnormal ALP: 0Abnormal creatinine: 1 |

| Anness A. et al. (2020)35 | 1 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): 571 XLDH (U/L): 194 X | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: 0 | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 13ALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 0Abnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Edwards K. et al. (2020)36 | 1 | AST (U/L): NDALT (U/L): 300 XLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: NDAbnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 250 XALP (U/L): 4000 XCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Aldossary B. et al. (2021)37 | 1 | AST (U/L): 12000 XALT (U/L): 8000 XLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 22.23ALP (U/L): 150Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Heckroth M.A. et al. (2020)38 | 2 | AST (U/L): 1214*ALT (U/L): 1285*LDH (U/L): 381 X | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: 1 | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 103.46ALP (U/L): 283.5Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Trejo-Paredes C. et al. (2020)39 | 1 | AST (U/L): 229 XALT (U/L): 167 XLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 376.2ALP (U/L): 162Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Legrand F. et al. (2020)40 | 1 | AST (U/L): 556ALT (U/L): 557LDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 36ALP (U/L): NDCreatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Roth C.N. et al. (2021)9 | 3 | AST (U/L): 117.6*ALT (U/L): 128*LDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 3Abnormal ALT: 3Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 188.1ALP (U/L): 1728Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 3Abnormal ALP: 3Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Durazo F.A. et al. (2021)10 | 1 | AST (U/L): 491 XALT (U/L): 175 XLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 324.9ALP (U/L): 2730Creatinine (mg/dl): ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Klindt C. et al. (2021)41 | 1 | AST (U/L): 470 XALT (U/L): 754 XLDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 1Abnormal ALT: 1Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 307.8ALP (U/L): 1700Mean creatinine: ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 1Abnormal ALP: 1Abnormal creatinine: ND |

| Lagana M.S. et al. (2020)42 | 40 | AST (U/L): 102*ALT (U/L): 68*LDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 33Abnormal ALT: 33Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 15.39ALP (U/L): NDAverage creatinine: 2.64mg/dl | Abnormal bilirubin: 0Abnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: 34 |

| Li X. et al. (2020)43 | 7 | AST (U/L): 48.7*ALT (U/L): 78.1*LDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 7Abnormal ALT: 7Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): NDALP (U/L): NDMean creatinine: ND | Abnormal bilirubin: NDAbnormal ALP: NDAbnormal creatinine: ND |

| Aby E.S. et al. (2020)44 | 2164 | AST (U/L): 40*ALT (U/L): 26*LDH (U/L): ND | Abnormal AST: 2164Abnormal ALT: 0Abnormal LDH: ND | Bilirubin (μmol/L): 8.55ALP (U/L): 74Mean creatinine: ND | Abnormal bilirubin: 0Abnormal ALP: 0Abnormal creatinine: ND |

X, highest measurement during the study; ND, not determined; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Once you have a patient with persistent and severe cholestasis, jaundice, high biochemical tests, will motivate the realization of a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast in which you can show in early stages a mild dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct, peri portal edema and a slightly dilated common bile duct with hyperenhancement.21

In the situation of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), it is usual to find in such patients a usual hepatic morphology with mild and diffuse intrahepatic biliary distension, marked rim and irregularity, as well as mild irregularity of the extrahepatic choledochus. In addition, diffuse22 peri ductal enhancement may be seen.

Ultrasound may demonstrate intrahepatic bile duct irregularity and a markedly thickened common bile duct. Then, if warranted, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed, which shows tortuous and attenuated intrahepatic bile ducts with extrahepatic ducts of normal caliber.23

TreatmentNot much is known about the implications of post-COVID cholangiopathy. Most of the reported cases used drugs whose main indication is other cholestatic diseases of different etiology. The indicated ones are ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and obeticholic acid (AOBTC). The aforementioned drugs do not have the purpose of resolving the disease. They can only stop the hepatic damage produced by the accumulation of bile acids that are not excreted. UDCA exerts its effect by inhibiting the absorption of bile acids at the intestinal level, as well as favoring the increase of bile secretion. In those patients whose response is unsuccessful with the use of UDCA, AOBTC can be used both drugs in combination in order to increase the potency and the efficacy of the medications.33

A certain number of patients due to their severe involvement may persist with an unfavorable prognosis even having already treated with the recommended medications. In them, it is suggested to use procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy25 as a measure to avoid obstructions due to biliary sedimentation that may be formed due to alterations in the biliary ducts.

Post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy and liver transplantationPatients have been reported to require liver transplantation because of the presenting complication of post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy leading to end-stage liver disease months after the initial diagnosis of COVID-19. A case series in the USA reported five patients who were referred for consideration of liver transplantation after experiencing persistent jaundice, liver failure and/or recurrent bacterial cholangitis.8 Another American case report describes sclerosing cholangitis after COVID-19 in a patient who seven months previously had COVID-19; this complication led to end-stage liver disease and deceased donor orthotopic transplantation.26 Another case report of a young adult who recovered from COVID-19 and subsequently developed end-stage liver disease from post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy, underwent liver transplantation and at 7-month follow-up treatment was successful.10

RecommendationsThe limited availability of prospective studies makes a more elaborate data synthesis difficult. Therefore, a synthesis of information was made from cases already reported in order to increase the available evidence. The objective is that in the future this research will allow more exhaustive prospective studies to be carried out on patients with post-COVID cholangiopathy and thus be able to improve the already known conclusions.

Ethical approvalThere is nothing to be declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.