Diarrhoea is the most common health problem among travellers from developed countries who visit developing countries and/or tropical and semi-tropical regions, and this diarrhoea is known for this reason as travellers’ diarrhoea (TD).1 More than 60% of cases of TD are caused by bacterial agents, of which diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) plays a leading role.2 Specifically, enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) are currently considered the most common causes of TD, and it is estimated that together both pathotypes cause about half of the cases of TD in Africa and Latin America and more than a third of the cases of TD in southeast Asia.1 While their relative importance as TD agents is less, other pathotypes such as verotoxigenic E. coli (VTEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), both typical (tEPEC) and atypical (aEPEC), and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) should also be considered as a diagnostic option in these types of infections.3–5

In November 2015, a stool sample from a two-year-old girl with a history of travel to Cuba was sent to the Microbiology Department of the Hospital Universitario Río Hortega [Río Hortega University Hospital]. Three days after returning from the trip, the girl had experienced a decrease in consistency and increase in frequency of her bowel movements, without any other associated symptoms. The physical examination was normal and no additional diagnostic tests were required, apart from the stool culture. The condition persisted for 15 days and resolved spontaneously, with administration of probiotics as the only therapeutic measure. In the stool culture the presence of norovirus, adenovirus, astrovirus and rotavirus was ruled out by immunochromatography (CerTest Biotec), and the most common bacterial enteropathogens—Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Hafnia, Aeromonas, Plesiomonas and Campylobacter—were ruled out by conventional microbiological methods. Taking into account the history of recent travel, the sample was sent to the Spanish National Microbiology Centre for the diagnosis of DEC infection. The different pathotypes were detected by PCR for the genes encoding the verotoxins of VTEC (vtx1, vtx2), the intimin of EPEC and VTEC (eae), the virulence plasmid of EAEC (aatA), the enterotoxins of ETEC (eltA, estA) and the invasion proteins of EIEC (ipaH), as well as the BFP adhesin (bfpA), that differentiates between tEPEC and aEPEC, from a stool culture of the sample in MacConkey agar (Becton-Dickinson), and the detected pathotypes were isolated.6 The isolates obtained were sequenced on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina). For the extraction of genomic DNA, the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) was used and “paired-end” libraries were generated using the Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina). From the readings obtained, the serotype, sequence type, virulence gene profile and resistance gene profile of each isolate were determined with the SerotypeFinder, MLST, VirulenceFinder and ResFinder tools, respectively, available on the Center for Genomic Epidemiology server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk//services). Additionally, the antibiotic sensitivity of the isolates was studied using the disc diffusion method, according to EUCAST and CLSI criteria. The antibiotic panel used included ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ertapenem, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, pefloxacin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, streptomycin, kanamycin and sulfamethoxazole.

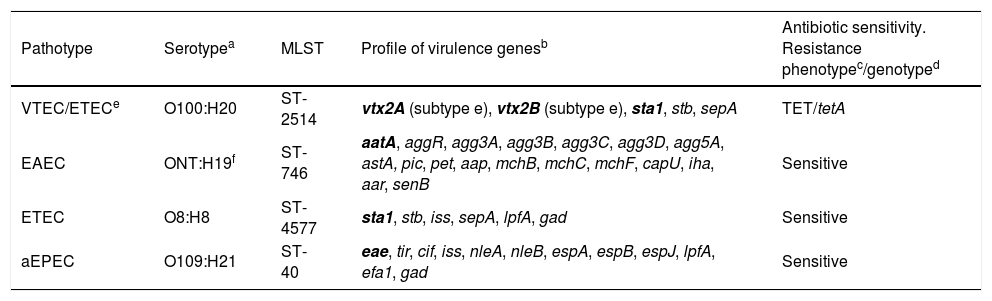

The sample was positive simultaneously for VTEC, EAEC, ETEC and aEPEC pathotypes, and the isolation of the four present DEC strains was obtained, the complete characterisation of which is shown in Table 1. Although mixed infections by DEC strains of different pathotypes, as well as coinfections of DEC strains with other bacterial as well as viral or parasitic enteropathogens, are not uncommon, especially in cases of TD,5,7,8 as far as we know, this is the first case of DEC infection in which the presence of four different pathotypes has been demonstrated. However, despite their frequent presence in children with diarrhoea, the clinical implication of some of these pathotypes, such as EAEC or aEPEC, is not clearly established, and has also been described in asymptomatic children. However, ETEC is a pathogenic group with a clear clinical implication, considered as a leading cause of TD in adults in developed countries and the most significant cause of childhood diarrhoea in developing countries.9 In this sense, the production of the ST-Ia heat-stable enterotoxin by the ETEC O8:H8 and VTEC/ETEC O100:H20 strains detected in this case would be primarily responsible for the clinical manifestations of the patient. The additional production of verotoxin 2e by the VTEC/ETEC O100:H20 hybrid pathotype strain would not imply a greater clinical implication of this strain, as it is a variant of low or no pathogenic verotoxin for humans.10

Characterisation of the four strains of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolated from the sample of a patient with travellers’ diarrhoea originating from Cuba.

| Pathotype | Serotypea | MLST | Profile of virulence genesb | Antibiotic sensitivity. Resistance phenotypec/genotyped |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTEC/ETECe | O100:H20 | ST-2514 | vtx2A (subtype e), vtx2B (subtype e), sta1, stb, sepA | TET/tetA |

| EAEC | ONT:H19f | ST-746 | aatA, aggR, agg3A, agg3B, agg3C, agg3D, agg5A, astA, pic, pet, aap, mchB, mchC, mchF, capU, iha, aar, senB | Sensitive |

| ETEC | O8:H8 | ST-4577 | sta1, stb, iss, sepA, lpfA, gad | Sensitive |

| aEPEC | O109:H21 | ST-40 | eae, tir, cif, iss, nleA, nleB, espA, espB, espJ, lpfA, efa1, gad | Sensitive |

Determined from the readings obtained from each isolate with SerotypeFinder (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk//services) selecting a minimum identity percentage of 90%.

Determined from the readings obtained from each isolate with VirulenceFinder (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk//services) selecting a minimum identity percentage of 90%. In bold, virulence genes that define the pathotype. sta1: gene that encodes the E. coli ST-Ia heat-stable enterotoxin.

The diffusion method with Mueller-Hinton agar discs (Becton-Dickinson) and the EUCAST and CLSI cut-off tables were used to interpret the diameter of the inhibition zones (version 7.0, 2017 and M100-S25, respectively). TET, tetracycline.

It should be noted that the complete characterisation of the four strains involved in this case, carried out by sequencing the entire genome, would not have been possible by conventional techniques, given the impossibility of maintaining a complete collection of antisera to determine the serotype or of using PCR to test the entire battery of virulence genes—and their respective variants—described so far, in addition to saving considerable time and effective work in the laboratory. On the other hand, the analysis of the sequences obtained was quick and simple, since they are bioinformatics tools with free access and are easy to handle for a non-expert user.

FundingThis study has been funded through the Health Research Fund (projects MPY-1042/14 and PI14CIII/00051).

Conflicts of interestNothing to declare.

We would like to thank Cristina García for her excellent work in the preparation of genomic libraries and the staff of the Genomics and Bioinformatics Units of the Spanish National Centre for Microbiology for their support in the sequencing of complete genomes and in the management of the sequences obtained. Sergio Sánchez would like to thank the Miguel Servet programme of the Health Research Fund for the funding of his contract (CP13/00237).

Please cite this article as: de Frutos M, Ramiro R, Pereña JI, Sánchez S. Infección mixta por cuatro patotipos diarreagénicos de Escherichia coli en un caso de diarrea del viajero: caracterización de los aislados obtenidos mediante secuenciación del genoma completo. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;2020:39–40.