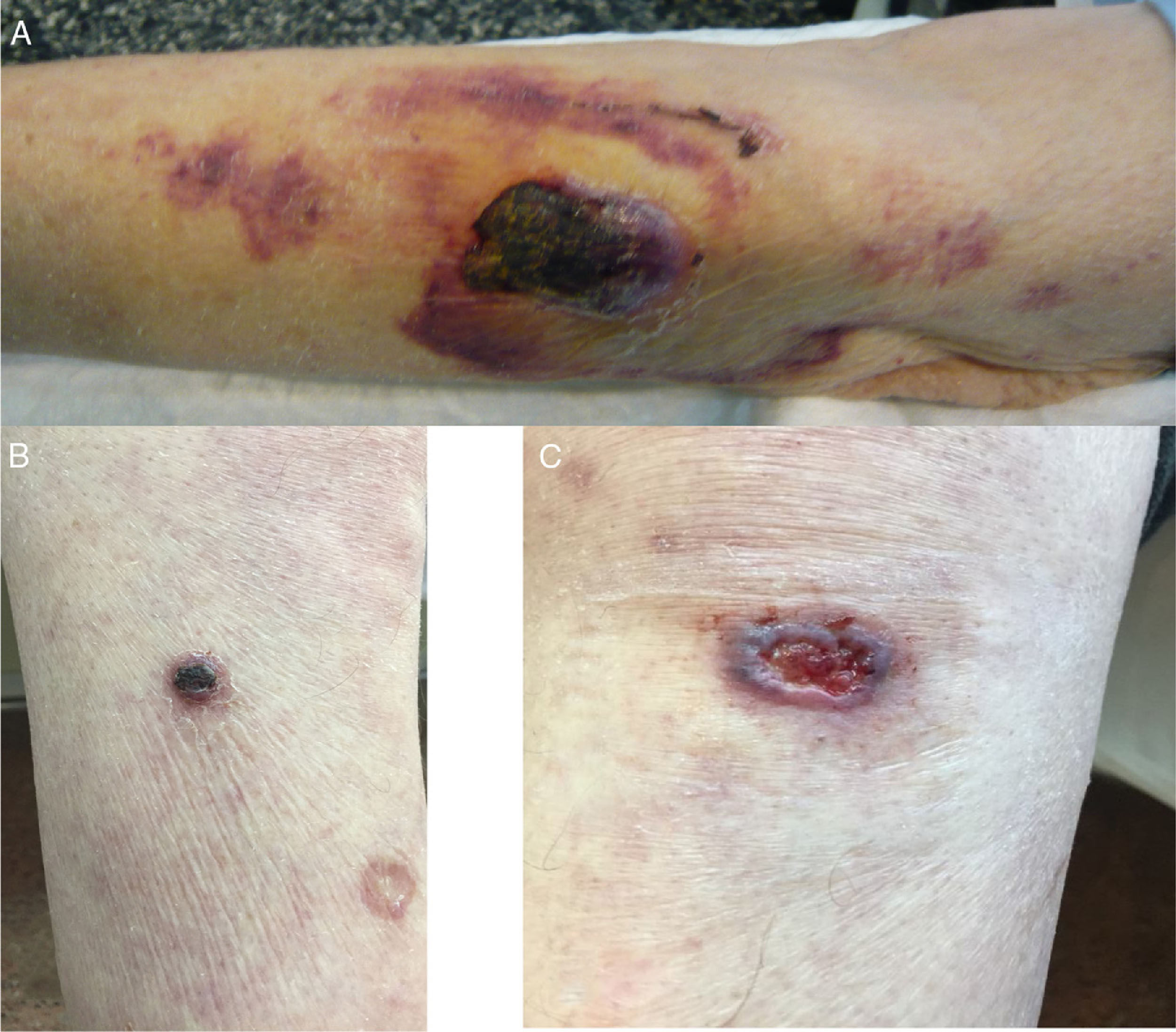

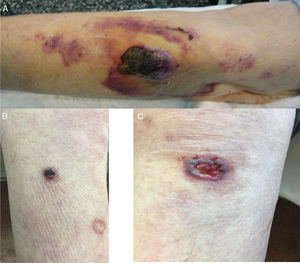

We present the case of a 78-year-old man with no known drug allergies, with a history of hypertension and prostate cancer with stage IVB bone metastases on symptomatic treatment with dexamethasone. He consulted for a skin lesion on his left arm which had appeared one month previously and progressively grown, with spontaneous bleeding, and another three on his lower limbs which had appeared in the previous two weeks; he stated that four months earlier he had a superficial graze on his left arm after scraping it on the branch of a cherry tree. He had no fever or other systemic symptoms. Physical examination (Fig. 1A–C) revealed an erosive/bleeding violaceous tumour on the back of the patient's left forearm measuring 3.5cm×2cm in diameter, with a superficial blackish scab, but no specific dermoscopic criteria for a primary skin tumour. He also had three similar but smaller lesions on his lower limbs.

Polymorphic skin lesions. (A) Back of left forearm: a poorly defined, stony tumour plaque with a blackish crusty surface, 3.5cm×2cm in diameter, with peri-lesional ecchymotic plaques. (B) Front of the right leg with two rounded plaques 1.5cm in diameter. (C) The left knee has a plaque with a diameter of 2.5cm with irregular, raised borders and a friable, bleeding centre.

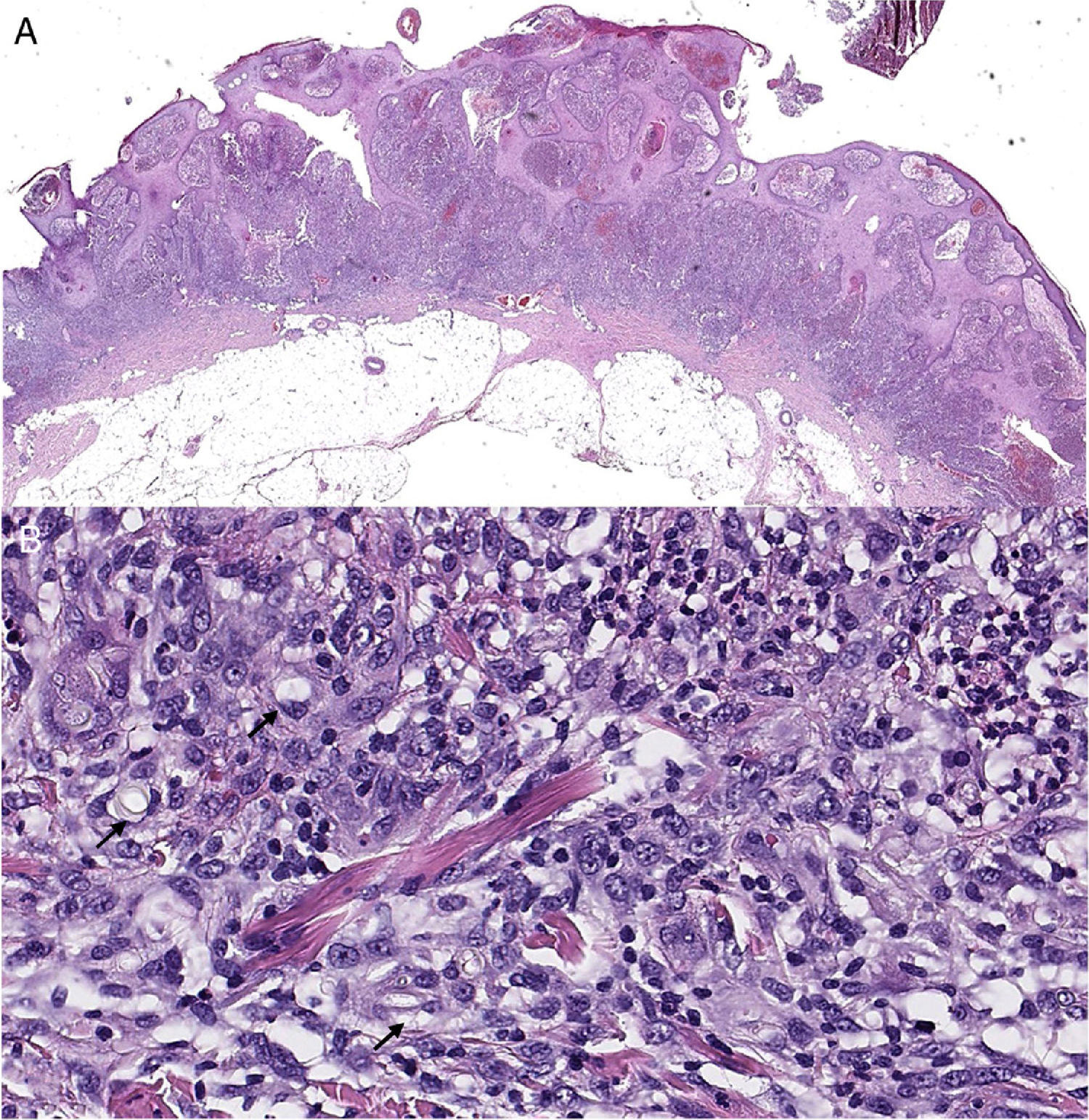

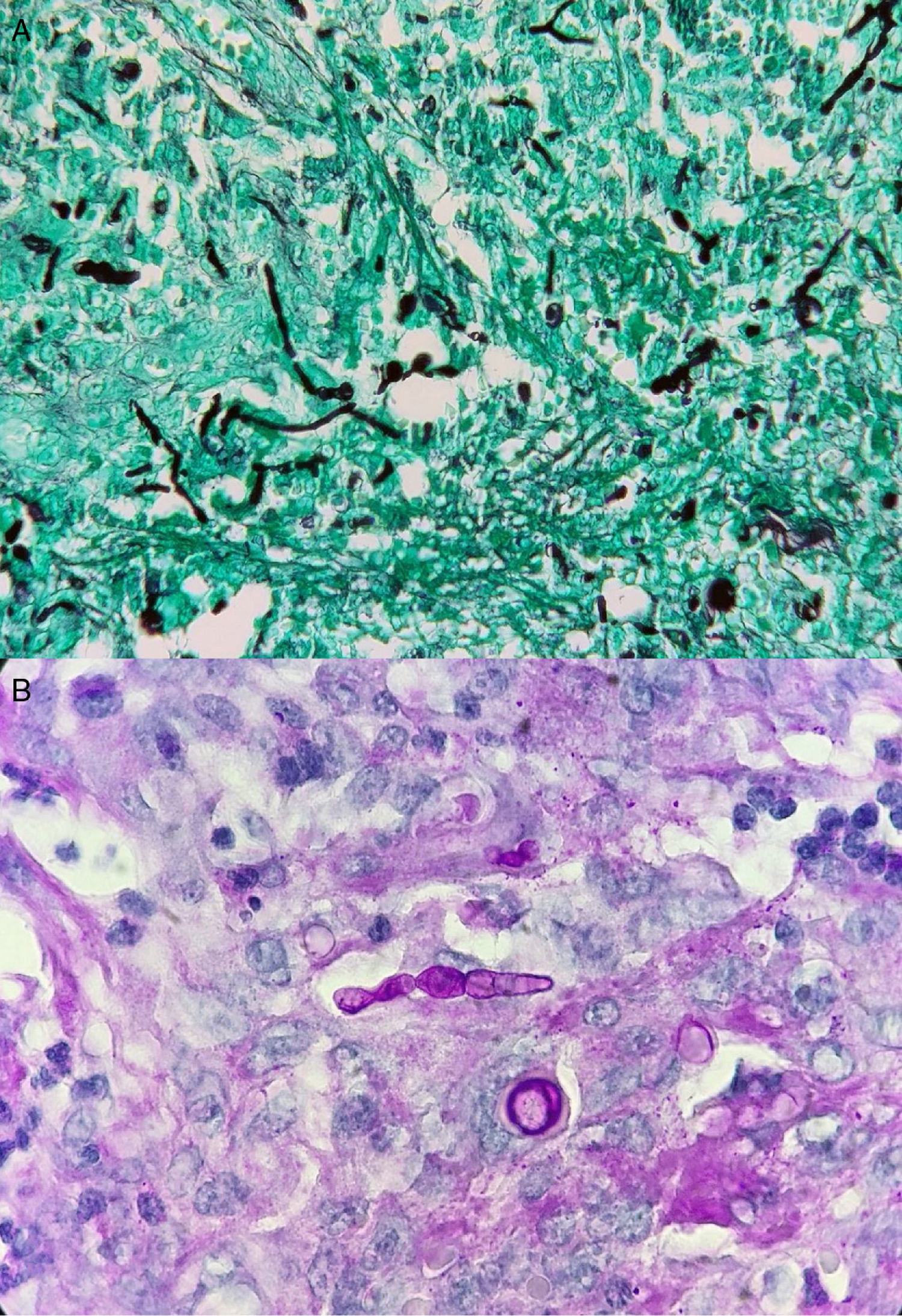

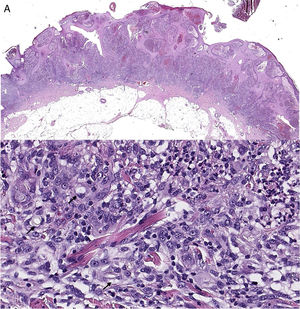

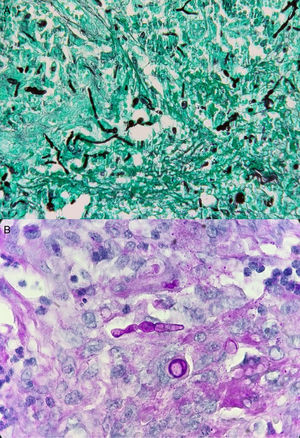

After complete surgical removal of the forearm skin lesion, subsequent histological study (Fig. 2A and B) revealed an inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary and reticular dermis composed of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with abscessing foci. Grocott and PAS stains (Fig. 3A and B) revealed abundant septate hyphae and chains of conidia.

Skin biopsy of left elbow lesion, haematoxylin-eosin (H&E). (A) Panoramic view: pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia with abundant inflammatory infiltrate. (B) At higher magnification, the inflammatory component is heterogeneous with abundant histiocytes/macrophages, and in a minor proportion a mixture of lymphocytes and neutrophils, in addition to proliferation of vessels. Refringent and laminar structures identified in macrophage cytoplasm (arrows).

The definitive diagnosis was arrived at by culture of a new biopsy. Colonies of a brownish-green filamentous fungus grew in Sabouraud agar after 2–3 days. Lactophenol blue staining showed the chains of muriform conidia characteristic of the genus Alternaria. The strain was sent to the reference laboratory and, by sequencing the 18S rRNA small ribosomal subunit, the species was identified as Alternaria alternata.

As the patient was terminally ill and refused further tests such as chest CT and long-standing intravenous or oral antifungal treatment, local cryotherapy was carried out, with subsequent application of a topical antifungal to the smaller lesions on his legs, which controlled progression of the lesions and reduced their size. The patient died a few weeks later of his underlying disease.

CommentsCutaneous alternariosis is a rare opportunistic fungal infection that comes under the grouping of phaeohyphomycosis (filamentous fungi capable of synthesising melanin). Alternaria spp. are frequently isolated on the ground, in vegetation or in the air. It rarely causes dermatological infection, as it requires a break in the skin barrier on exposed body surfaces, combined with severe immunosuppression, to cause skin disease in the middle and deep dermis.1,2 Although cases have also been described in healthy individuals, most occur in the context of transplants (especially solid organ), blood cancers and/or pharmacological immunosuppression. Only three cases have been reported to date in which solid tumours acted as a predisposing or contributing factor to the state of immunosuppression.3–6 The clinical presentation varies, from erythematous macules to violaceous papules, to nodules with a tendency to ulceration.7 They can simulate other conditions such as primary skin tumours or, as in our case, metastasis. However, the typical biopsy finding of granulomatous inflammation and septate hyphae refocused the case; the culture finally confirmed the diagnosis. As there have been no randomised clinical trials, there is no standardised treatment.

The most effective therapy consists of reversing the state of immunosuppression, and if they are resectable, surgical excision is recommended. To avoid recurrence, antifungal treatment with itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole or amphotericin B is usually added, all of which have shown susceptibility in vitro, although there is no consensus on duration or dose. Alternative and/or adjuvant treatments have been described, such as photodynamic therapy, cryotherapy or local hyperthermia, but in each case results are mixed and poorly contrasted.8

FundingThis work has been funded by the Autonomous Government of Aragon (Grupo de Investigación Agua y Salud Ambiental [Water and Environmental Health Research Group], B43_20R), Feder 2014–2020 “Building Europe from Aragon” and Universidad de Zaragoza (UZ2018-BIO-01).

Please cite this article as: Lapeña Casado A, Beltrán Rosel A, Lezcano Biosca V, Ara Martín M. Tumoración sangrante de rápida aparición en paciente inmunodeprimido. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:201–203.