Fibroids are common benign gynecological tumors but a rare finding in adolescents. Although infrequent, some symptomatic cases have been described in literature.

Main symptoms and/or clinical findingsA 16-year-old Caucasian patient came to our attention for abdominal pain and dysmenorrhea appeared two months before. Her gynecological history was characterized by regular menstrual cycles, normal in quantity, with dysmenorrhea. Bimanual pelvic examination revealed an anteverted mobile uterus, no adnexal tenderness or masses. Speculum examination showed a normal cervix. No vaginal bleeding or discharge was observed during the visit.

Main diagnosesTransabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound demonstrated an anteverted uterus of 71mm×44×48mm, with a heterogeneous myometrial structure and a hypoechoic subserosal-intramural mass (FIGO leiomyoma subclassification system: O-4) localized in the posterior uterine wall, measuring 26mm×19mm×16mm, slightly vascularized at the Color-Doppler (Color Score 2). Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the ultrasound diagnosis.

Therapeutic interventions and outcomesConsidering pelvic mass dimension and the patient age, a “wait and see” approach was chosen and the patient was re-evaluated a month and three months after the first ultrasound. The second and the third transvaginal ultrasound exam showed an unchanged picture.

ConclusionThe management of leiomyoma in young patients should be targeted to dimension and symptoms of the mass. When facing myomas of small dimension, paucisymptomatic or asymptomatic, with no signs of malignity, we suggest an expectant management.

Los fibromas son tumores ginecológicos benignos comunes, pero son un hallazgo raro en los adolescentes. Aunque son poco frecuentes, en la literatura se han descrito algunos casos sintomáticos.

Principales síntomas y/o hallazgos clínicosPaciente caucásica de 16 años que acudió a nuestra consulta por dolor abdominal y dismenorrea de aparición 2 meses antes. Sus antecedentes ginecológicos se caracterizaron por ciclos menstruales regulares, normales en cantidad, con dismenorrea. El examen pélvico bimanual reveló un útero móvil en anteversión, sin dolor a la palpación ni masas anexiales. El examen con espéculo mostró un cuello uterino normal. Durante la visita no se observó sangrado ni secreción vaginal.

Diagnósticos principalesLa ecografía transabdominal/transvaginal demostró un útero antevertido de 71×44×48mm, con una estructura miometrial heterogénea y una masa subseroso-intramural hipoecoica (sistema de subclasificación de leiomiomas FIGO: O-4) localizada en la pared posterior del útero, de 26×19×16mm, ligeramente vascularizado en el Doppler color (Color Score 2). La resonancia magnética confirmó el diagnóstico ecográfico.

Intervenciones terapéuticas y resultadosTeniendo en cuenta la dimensión de la masa pélvica y la edad de la paciente, se optó por un enfoque de «esperar y ver» y la paciente fue reevaluada un mes y 3 meses después de la primera ecografía. El último examen de ultrasonido transvaginal mostró una imagen sin cambios.

ConclusiónEl tratamiento del leiomioma en los pacientes jóvenes debe centrarse en el tamaño y los síntomas de la masa. Ante miomas de pequeño tamaño, paucisintomáticos o asintomáticos, sin signos de malignidad, sugerimos un manejo expectante.

Uterine leiomyomas, also known as fibroids, are neoformations originating from smooth muscle cells of the myometrium. Fibroids are extremely heterogeneous in their location, dimension and clinical presentation. When symptomatic, myomas can present themselves, depending on their size and location in the uterus, with heavy bleeding or abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, bulk symptoms (pelvic pressure, back or abdominal pain), urinary or gastrointestinal symptoms (pollakiuria or constipation).1 Fibroids can also be associated with infertility and other poor obstetrical outcomes (increased risk of preterm labor, cesarean delivery, fetal malpresentation and growth restriction).2,3

Myomas are the most common form of benign tumors of the uterus but notable differences are found in their prevalence and presentation. Fibroids are more frequent, tend to present at a younger age, are greater in number and larger in size in women of African ancestry.4 Other risk factors identified include: nulliparity, hypertension, obesity, late menopause and early menarche, familiarity.5

Considering that fibroid development and growth is strongly influenced by female hormones, leiomyomas mainly interest women during reproductive years and typically regress following menopause.6 Therefore, fibroids are a common finding in women between the ages of 30 and 50 but are extremely rare in adolescents. At 25–30 years the incidence of fibroids is only 0.31 per 1000 women years, but by ages 45–50 the incidence has increased 20-fold to 6.20 per 1000 women years.7 From 1969, only 35 cases in young women have been reported.

In this work we present the case of a 16-year-old patient addressed to the gynecologist for abdominal pain and dysmenorrhea, who was diagnosed with a uterine leiomyoma. In addition, we provide an updated review of the literature, including the management of myomas in adolescent patients.

Case reportInformation of the patientA 16-year-old Caucasian patient came to our attention for abdominal pain and dysmenorrhea appeared two months before. She had an unremarkable medical, surgical and family history. Her gynecological history was also mute and was characterized by regular menstrual cycles, normal in quantity, with a dysmenorrhea 8 out of 10 on the Visual Analogue Scale.

Clinical findingsPatient vital signs were normal. On examination, Tanner staging was appropriate for age. Her body mass index was 26. Bimanual pelvic examination revealed an anteverted mobile uterus, no adnexal tenderness or masses. Speculum examination showed a normal cervix. No vaginal bleeding or discharge was observed during the visit.

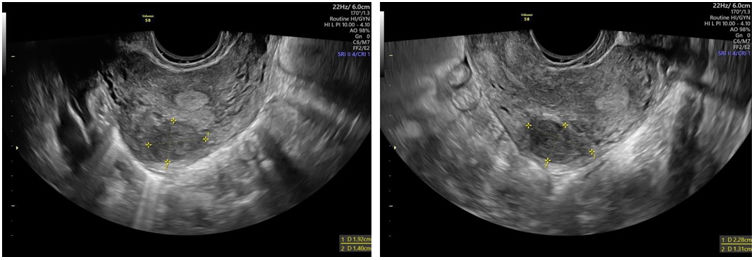

Diagnostic evaluationTransabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound (Mindray DC-80A, convex ultrasound transducer, 1.3–5.7MHz, China) demonstrated an anteverted uterus of 71mm×44mm×48mm, with a heterogeneous myometrial structure and a hypoechoic subserosal-intramural mass (FIGO leiomyoma subclassification system: O-4) localized in the posterior uterine wall, measuring 26mm×19mm×16mm, slightly vascularized at the Color-Doppler (Color Score 2). The endometrium had a three-layers pattern, synchronized to her menstrual cycle. Ovaries were unremarkable bilaterally. No pelvic fluid was observed. The pelvis MRI (Siemens AVANTO 1.5T) showed an oval mass on the upper left wall of the uterine myometrium (axial dimensions 25mm×15mm), with a low to intermediate signal intensity compared with the normal myometrium in the T1-weighted sequences acquired on axial and sagittal planes and an intermediate to high signal intensity compared with the normal myometrium in the T2-weighted sequences acquired on an axial and sagittal planes, compatible with an hypercellular variant of an uterine leiomyoma. The post-contrast administration sequences acquired during arterial and venous phases showed an homogenous enhancement similar to the myometrium which is consistent with non-degenerated fibroids; the finding was confirmed with DWI sequences (b1000) and ADC mapping in which there was no evidence of significant restriction in the diffusion pattern inside the fibroid mass.

Therapeutic interventionConsidering pelvic mass dimension, a “wait and see” approach was chosen and the patient was re-evaluated a month after and three months after the first ultrasound. In this period, in order to alleviate patient's symptoms (abdominal pain and dysmenorrea), we prescribed paracetamol 1000mg orally twice a day during menstruation.

Monitoring and resultsThe second and the third transvaginal ultrasound exam (GE Voluson S8, micro-convex transducer, 4–10MHz, South Korea), a month and three months after the first exam respectively, showed an unchanged picture (Fig. 1A and B): a hypoechoic subserosal-intramural mass (FIGO leiomyoma subclassification system: O-4) localized in the posterior uterine wall, measuring 23mm×19mm×13mm, slightly vascularized at the Color-Doppler (Color Score 2). 3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound revealed a normal uterine cavity.

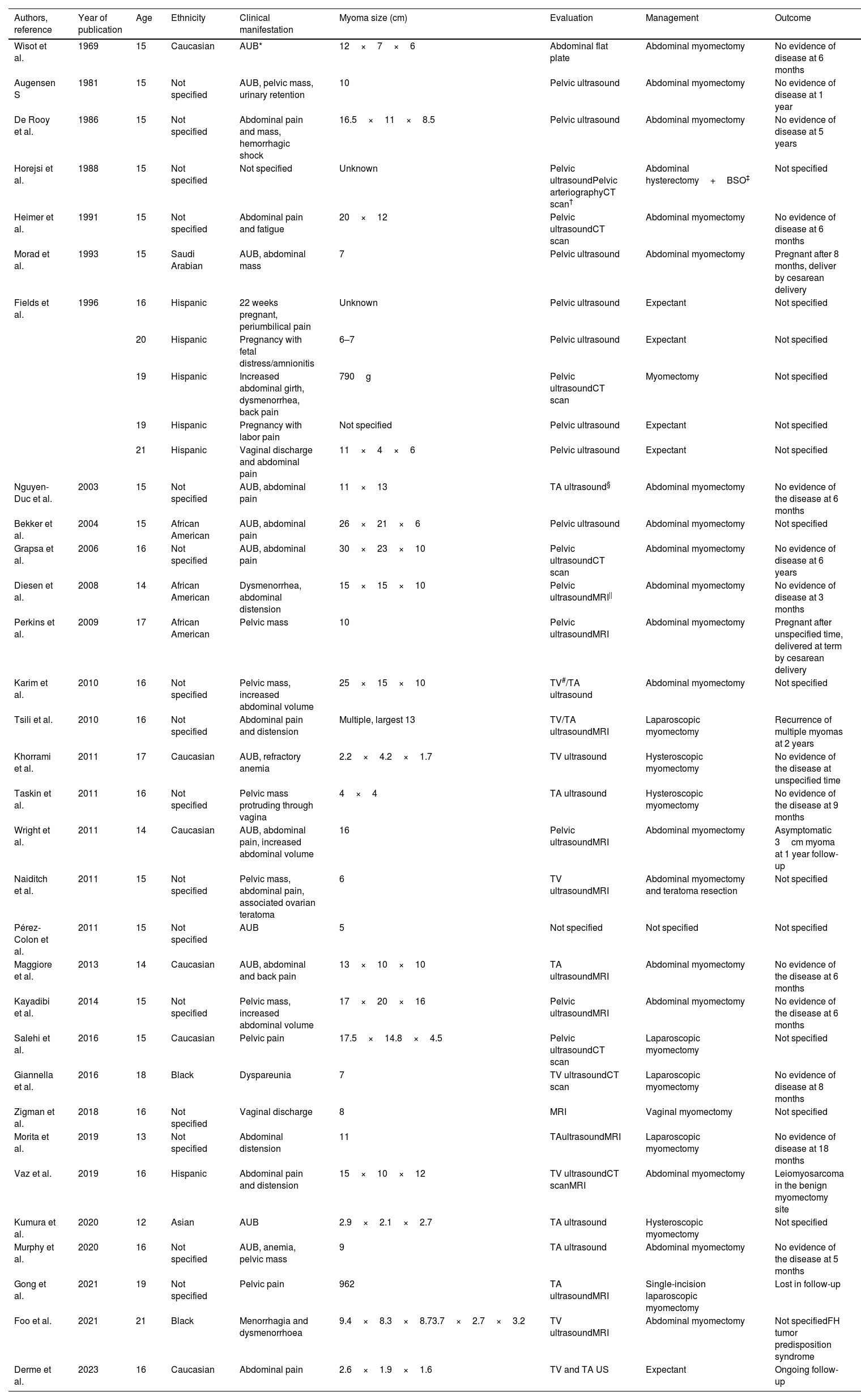

DiscussionIn this report we add another case of symptomatic uterine fibroid in an adolescent patient to the very few described in the last 53 years (Table 1).

Literature report of myomas in adolescents.

| Authors, reference | Year of publication | Age | Ethnicity | Clinical manifestation | Myoma size (cm) | Evaluation | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wisot et al. | 1969 | 15 | Caucasian | AUB* | 12×7×6 | Abdominal flat plate | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 6 months |

| Augensen S | 1981 | 15 | Not specified | AUB, pelvic mass, urinary retention | 10 | Pelvic ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 1 year |

| De Rooy et al. | 1986 | 15 | Not specified | Abdominal pain and mass, hemorrhagic shock | 16.5×11×8.5 | Pelvic ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 5 years |

| Horejsi et al. | 1988 | 15 | Not specified | Not specified | Unknown | Pelvic ultrasoundPelvic arteriographyCT scan† | Abdominal hysterectomy+BSO‡ | Not specified |

| Heimer et al. | 1991 | 15 | Not specified | Abdominal pain and fatigue | 20×12 | Pelvic ultrasoundCT scan | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 6 months |

| Morad et al. | 1993 | 15 | Saudi Arabian | AUB, abdominal mass | 7 | Pelvic ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | Pregnant after 8 months, deliver by cesarean delivery |

| Fields et al. | 1996 | 16 | Hispanic | 22 weeks pregnant, periumbilical pain | Unknown | Pelvic ultrasound | Expectant | Not specified |

| 20 | Hispanic | Pregnancy with fetal distress/amnionitis | 6–7 | Pelvic ultrasound | Expectant | Not specified | ||

| 19 | Hispanic | Increased abdominal girth, dysmenorrhea, back pain | 790g | Pelvic ultrasoundCT scan | Myomectomy | Not specified | ||

| 19 | Hispanic | Pregnancy with labor pain | Not specified | Pelvic ultrasound | Expectant | Not specified | ||

| 21 | Hispanic | Vaginal discharge and abdominal pain | 11×4×6 | Pelvic ultrasound | Expectant | Not specified | ||

| Nguyen-Duc et al. | 2003 | 15 | Not specified | AUB, abdominal pain | 11×13 | TA ultrasound§ | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at 6 months |

| Bekker et al. | 2004 | 15 | African American | AUB, abdominal pain | 26×21×6 | Pelvic ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | Not specified |

| Grapsa et al. | 2006 | 16 | Not specified | AUB, abdominal pain | 30×23×10 | Pelvic ultrasoundCT scan | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 6 years |

| Diesen et al. | 2008 | 14 | African American | Dysmenorrhea, abdominal distension | 15×15×10 | Pelvic ultrasoundMRI|| | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 3 months |

| Perkins et al. | 2009 | 17 | African American | Pelvic mass | 10 | Pelvic ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | Pregnant after unspecified time, delivered at term by cesarean delivery |

| Karim et al. | 2010 | 16 | Not specified | Pelvic mass, increased abdominal volume | 25×15×10 | TV#/TA ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | Not specified |

| Tsili et al. | 2010 | 16 | Not specified | Abdominal pain and distension | Multiple, largest 13 | TV/TA ultrasoundMRI | Laparoscopic myomectomy | Recurrence of multiple myomas at 2 years |

| Khorrami et al. | 2011 | 17 | Caucasian | AUB, refractory anemia | 2.2×4.2×1.7 | TV ultrasound | Hysteroscopic myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at unspecified time |

| Taskin et al. | 2011 | 16 | Not specified | Pelvic mass protruding through vagina | 4×4 | TA ultrasound | Hysteroscopic myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at 9 months |

| Wright et al. | 2011 | 14 | Caucasian | AUB, abdominal pain, increased abdominal volume | 16 | Pelvic ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | Asymptomatic 3cm myoma at 1 year follow-up |

| Naiditch et al. | 2011 | 15 | Not specified | Pelvic mass, abdominal pain, associated ovarian teratoma | 6 | TV ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy and teratoma resection | Not specified |

| Pérez-Colon et al. | 2011 | 15 | Not specified | AUB | 5 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Maggiore et al. | 2013 | 14 | Caucasian | AUB, abdominal and back pain | 13×10×10 | TA ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at 6 months |

| Kayadibi et al. | 2014 | 15 | Not specified | Pelvic mass, increased abdominal volume | 17×20×16 | Pelvic ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at 6 months |

| Salehi et al. | 2016 | 15 | Caucasian | Pelvic pain | 17.5×14.8×4.5 | Pelvic ultrasoundCT scan | Laparoscopic myomectomy | Not specified |

| Giannella et al. | 2016 | 18 | Black | Dyspareunia | 7 | TV ultrasoundCT scan | Laparoscopic myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 8 months |

| Zigman et al. | 2018 | 16 | Not specified | Vaginal discharge | 8 | MRI | Vaginal myomectomy | Not specified |

| Morita et al. | 2019 | 13 | Not specified | Abdominal distension | 11 | TAultrasoundMRI | Laparoscopic myomectomy | No evidence of disease at 18 months |

| Vaz et al. | 2019 | 16 | Hispanic | Abdominal pain and distension | 15×10×12 | TV ultrasoundCT scanMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | Leiomyosarcoma in the benign myomectomy site |

| Kumura et al. | 2020 | 12 | Asian | AUB | 2.9×2.1×2.7 | TA ultrasound | Hysteroscopic myomectomy | Not specified |

| Murphy et al. | 2020 | 16 | Not specified | AUB, anemia, pelvic mass | 9 | TA ultrasound | Abdominal myomectomy | No evidence of the disease at 5 months |

| Gong et al. | 2021 | 19 | Not specified | Pelvic pain | 962 | TA ultrasoundMRI | Single-incision laparoscopic myomectomy | Lost in follow-up |

| Foo et al. | 2021 | 21 | Black | Menorrhagia and dysmenorrhoea | 9.4×8.3×8.73.7×2.7×3.2 | TV ultrasoundMRI | Abdominal myomectomy | Not specifiedFH tumor predisposition syndrome |

| Derme et al. | 2023 | 16 | Caucasian | Abdominal pain | 2.6×1.9×1.6 | TV and TA US | Expectant | Ongoing follow-up |

The first case was presented by Wisot et al. in 1969. Since then, a total of 35 patients, including the one whom case we describe, were identified. The youngest was aged 12-year-old and the oldest aged 21-year-old (mode 15-year-old). Most of them reported abnormal uterine bleeding, followed by abdominal pain. Other patients described abdominal mass and distention, anemia and dysmenorrhea. All of them, except one, performed at least an ultrasound (transabdominal US or transvaginal US). In 13 cases the diagnostic was completed with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and in 7 cases a computer tomography scan (CT) was performed. Myomectomy was the most common surgical treatment chosen (28 cases), either approached via hysteroscopy (3 cases), laparoscopy (5 cases), or laparotomy (18 cases). One patient underwent a vaginal myomectomy and only one patient underwent a hysterectomy. The expectant management was preferred in 5 patients, of whom 4 were pregnant. The histological examination did not reveal a malignity in any cases of the ones reported. In 14 cases, there was no evidence of the disease in a variable period of follow-up time (3 months–6 years). In 2 cases there was a recurrence of the fibroids, respectively, at the 1 year follow-up and the 2 years follow-up. In one case a leiomyosarcoma was described in the previous benign myomectomy site. In 2 cases a pregnancy followed the leiomyoma diagnosis and the surgical treatment and both patients underwent a cesarean section.

Our case presents the same characteristics of the ones reported in literature, concerning symptoms and methods of diagnostic. Considering the dimension of the fibroid which affected our patient and the absence of any sign of malignity at the ultrasound and MRI performed, an expectant management was preferred, despite the vast majority of the cases described.

Gynecological symptoms in adolescents often recognize a different etiology from the adult population. Abnormal uterine bleeding is typically due to anovulation secondary to the immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis.8 The majority of cases of dysmenorrhea are primary or functional and, when secondary, dysmenorrhea is typically attributed to endometriosis.9 In the adolescent age group, the distinct possibility of a müllerian anomaly must also be considered. Abdominal distension, when due to gynecological disorders, is often reconducted to an ovarian mass. As shown, uterine fibroids can be found in adolescent patients, although rare. For this reason the diagnosis of leiomyoma should be taken into account even in younger population.

The approach to a woman presenting the described symptoms should always include the evaluation of family history (familiarity for gynecological cancers and fibroids) and a gynecological visit. Sonography is the first line imaging exam. When possible, the combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach is preferred. Transvaginal method is generally chosen as it allows better evaluation of patients with retroverted uterus, inadequate bladder distension, significant bowel gas or obese patients. Transabdominal method, however, is superior for the assessment of large and fundal leiomyomas and it is appropriate even for virgo patients. The examinator should provide a detailed description of the position and the diameter of the lesions, in order to facilitate the follow-up of the mass, according to the FIGO classification system. In addition to ultrasound, MRI can improve further characterization of soft tissues and of mass features such as margins, vascularization, necrosis and growth. The differential diagnosis between leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas remains, however, difficult.

Different options are currently available for the treatment of uterine leiomyomas. Medical strategies include contraceptive steroids, selective progesterone receptor modulators, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists, aromatase inhibitors. Other surgical and non-surgical approaches include hysterectomy, myomectomy by hysteroscopy, laparotomy or laparoscopy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) and other interventions performed under radiologic or ultrasound.10 Regarding the management of leiomyomas in adolescents, there are no specific guidelines for this age group. Although fertility preservation is crucial, the treatment proposed should always be targeted to patient desire, symptoms and to dimension of the fibroid.

In the cases reported in literature, most of the patients underwent myomectomy, which can be a valid option for large, symptomatic fibroid not responsive to medical therapy. Extensive counseling regarding recurrence after surgical treatment and future obstetrical implications, such as the possible need to perform a cesarean section, should be provided to the patients. When facing myomas of small dimension, paucisymptomatic or asymptomatic, with no signs of malignity, we suggest, however, an expectant management. A strict echographic follow-up is mandatory to monitor increase in dimension or number of fibroid or the appearance of suspicious signs.

In conclusion, uterine leiomyomas are uncommon yet encountered in younger fertile women and their treatment should be targeted.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Patient consentThe authors declare that the protocols of their institutions on the publication of patient data have been followed and the privacy has been respected.

FundingThe authors certify that there is no financial support.

Conflict of interestThe authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.