Food allergies (FAs) affect 2–4% of school-aged children in developed countries and strongly impact their quality of life. The prevalence of FA in Chile remains unknown.

MethodsCross-sectional survey study of 488 parents of school-aged children from Santiago who were asked to complete a FA screening questionnaire. Parents who reported symptoms suggestive of FA were contacted to answer a second in-depth questionnaire to determine immediate hypersensitivity FA prevalence and clinical characteristics of school-aged Chilean children.

ResultsA total of 455 parents answered the screening questionnaire: 13% reported recurrent symptoms to a particular food and 6% reported FA. Forty-three screening questionnaires (9%) were found to be suggestive of FA. Parents of 40 children answered the second questionnaire; 25 were considered by authors to have FA. FA rate was 5.5% (95% CI: 3.6–7.9). Foods reported to frequently cause FA included walnut, peanut, egg, chocolate, avocado, and banana. Children with FA had more asthma (20% vs. 7%, P<0.02) and atopic dermatitis (32% vs. 13%, P<0.01) by report. The parents of children with FA did not report anaphylaxis, but 48% had history compatible with anaphylaxis. Of 13 children who sought medical attention, 70% were diagnosed with FA; none were advised to acquire an epinephrine autoinjector.

ConclusionUp to 5.5% of school-aged Chilean children may suffer from FA, most frequently to walnut and peanut. It is critical to raise awareness in Chile regarding FA and recognition of anaphylaxis, and promote epinephrine autoinjectors in affected children.

Food allergy (FA) is defined as an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food.1 FA has been associated with an impaired quality of life, limited social interactions, a heightened risk of severe allergic reactions and potential fatality, and high socioeconomic costs.2–5 The real prevalence of FA is difficult to establish since most studies have either focused on specific populations or only on selected food allergens, or have used different protocols and definitions of FA. Because FA prevalence depends on the eating habits and the ethnic background of the studied population, FA rates and foods involved also vary internationally. A recent meta-analysis of 51 studies reported that the self-reported prevalence of FA ranged from 3% to 35%.6

Despite an increasing prevalence of asthma and allergic rhinitis in Chile,7,8 no data on FA epidemiology are available to date. Vio et al. reported parental perception of food-related symptoms to be as high as 39% in Chilean children.9 In this study, one-third of the parents who described food-related symptoms eliminated the suspected food from the diet. However, the study did not mention clinical characteristics of reactions, temporality of symptoms, or if physician diagnosis of FA was made. Thus, the prevalence of FA in Chilean children is unknown. The objective of this study is to evaluate the prevalence and clinical characteristics of parent-reported FA in school-aged children from Santiago, Chile.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a population based cross-sectional survey study in Santiago, Chile, between September 2011 and December 2012. Population sampling was made by convenience in five private schools from different areas of Santiago, each school having three classes per grade. Parents of children attending kindergarten, 5th grade and 9th grade at the moment of recruitment were invited to participate in the study (i.e. ∼5, 10, and 15-year-old children). Recruitment took place at parent-teacher meetings regularly scheduled by the participant schools. Each school was approached only once and at that time recruitment took place in all grades and classes simultaneously (kindergarten, 5th grade and 9th grade). During parent-teacher meetings, parental informed consent to participate in the study was obtained and then parents were asked to answer a screening questionnaire about food allergies (FAs). If the answers of this questionnaire suggested that the child possibly suffered from FA, the parents were contacted telephonically to answer an extended questionnaire about the child's food-induced symptoms. Children with a second extended questionnaire that was convincing of FA were considered to have FA by the study authors.

Reactions to food were considered to be “convincing” if the organ systems affected and symptoms were typical of those involved in immediate hypersensitivity allergic reactions (skin with hives and angio-oedema; respiratory tract with trouble breathing, wheezing or throat tightness; and gastrointestinal tract with vomiting and diarrhoea) and occurred within 2h of ingestion. It has previously been reported that these criteria have high sensitivity for positive specific food IgE (immediate hypersensitivity) in affected patients.10,11

The Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile School of Medicine approved this study.

Questionnaires:

Two different FA questionnaires were applied in this study: a screening questionnaire and an extended in-depth questionnaire. Both questionnaires were adapted from surveys originally published in English and which were validated for this study by translation to Spanish and retranslation to English. The screening questionnaire was modified from Marrugo et al.,12 and was self-applied by parents during parent–teacher meetings. This questionnaire collected basic demographic and clinical information about the child: gender, age, allergic diseases, food-related recurrent symptoms, foods involved, parental suspicion of FA, elimination diets and physician diagnosis of FA.

The second questionnaire was applied telephonically to the parents by the authors and was adapted from a US-based telephone survey conducted by Sicherer et al.,11 This questionnaire collected in-depth information on food-related recurrent symptoms, foods involved, temporality of symptoms, number of reactions, age of first exposure to foods, history of medical attention, physician diagnosis of FA, treatments prescribed during allergic reactions, and prescription of epinephrine autoinjectors.

Statistical analysisUsing an estimated prevalence of self-reported FA of 13%, an absolute error of three percent and 95% confidence level, we obtained a calculated sample size of 447 children which was considered representative of the total population of five schools in Santiago (5850 children).

The data obtained were analysed using the PASW Statistics software package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA) and OpenEpi software version 2.3.1 (www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2011/23/06, accessed 2013/01/22).13 Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and we used Chi square test to examine the association of FA with other atopic diseases, age, and season of birth. Rates are reported as rate (95% confidence intervals) per 100 inhabitants. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

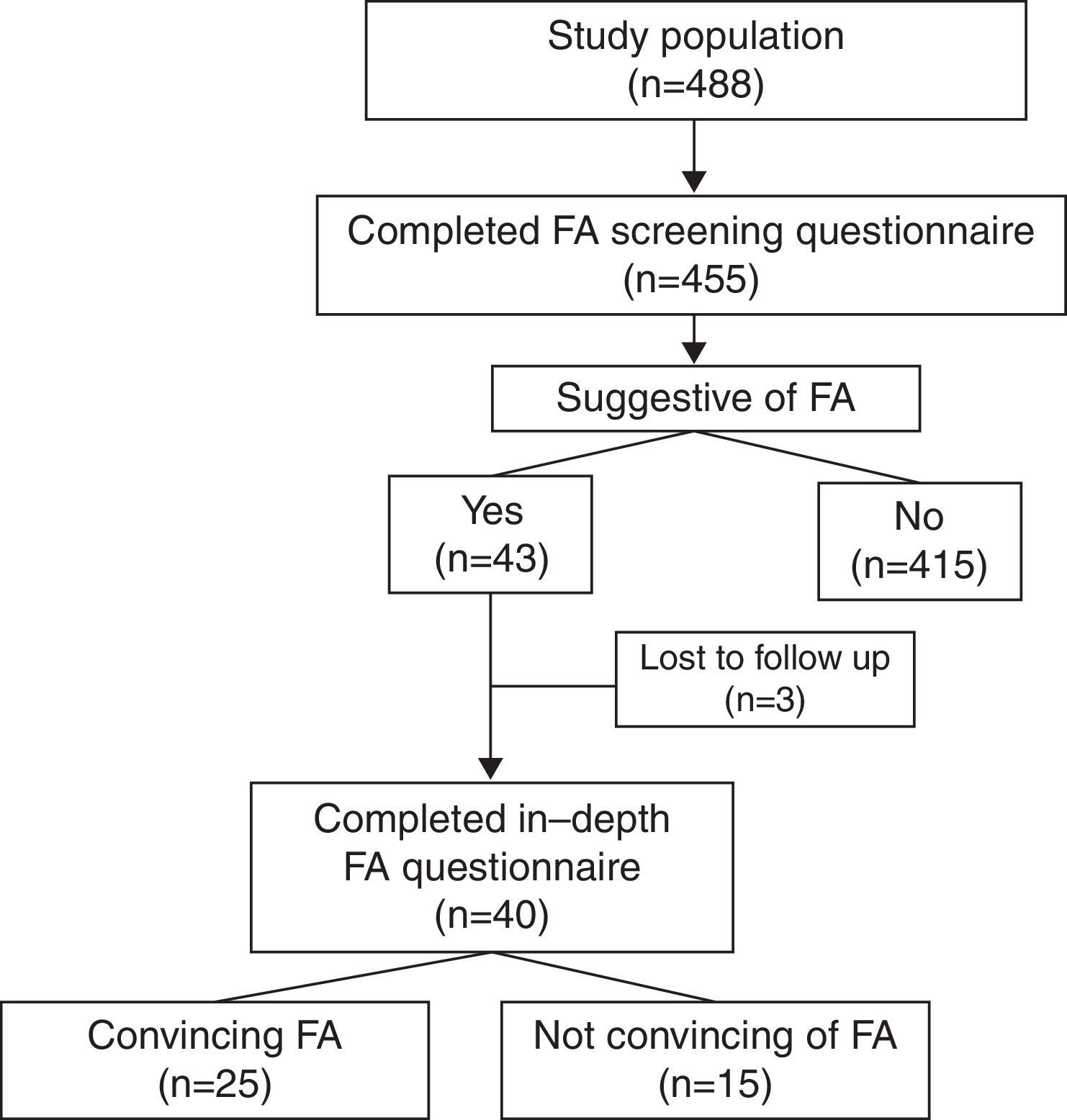

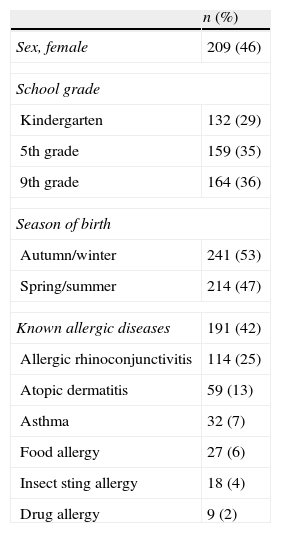

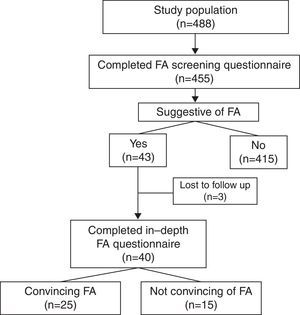

ResultsA total of 488 screening questionnaires were delivered and 455 were answered (response rate of 93%) (Fig. 1). Fifty-four percent of the population was male. At the time of the study, 29% of them were attending kindergarten, 35% fifth grade, and 36% ninth grade. Forty-two percent (n=191) of the surveyed parents reported that their child suffered from an allergic disease (Table 1). Parental report of FA in this same question was 6%.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (n=455).

| n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 209 (46) |

| School grade | |

| Kindergarten | 132 (29) |

| 5th grade | 159 (35) |

| 9th grade | 164 (36) |

| Season of birth | |

| Autumn/winter | 241 (53) |

| Spring/summer | 214 (47) |

| Known allergic diseases | 191 (42) |

| Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis | 114 (25) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 59 (13) |

| Asthma | 32 (7) |

| Food allergy | 27 (6) |

| Insect sting allergy | 18 (4) |

| Drug allergy | 9 (2) |

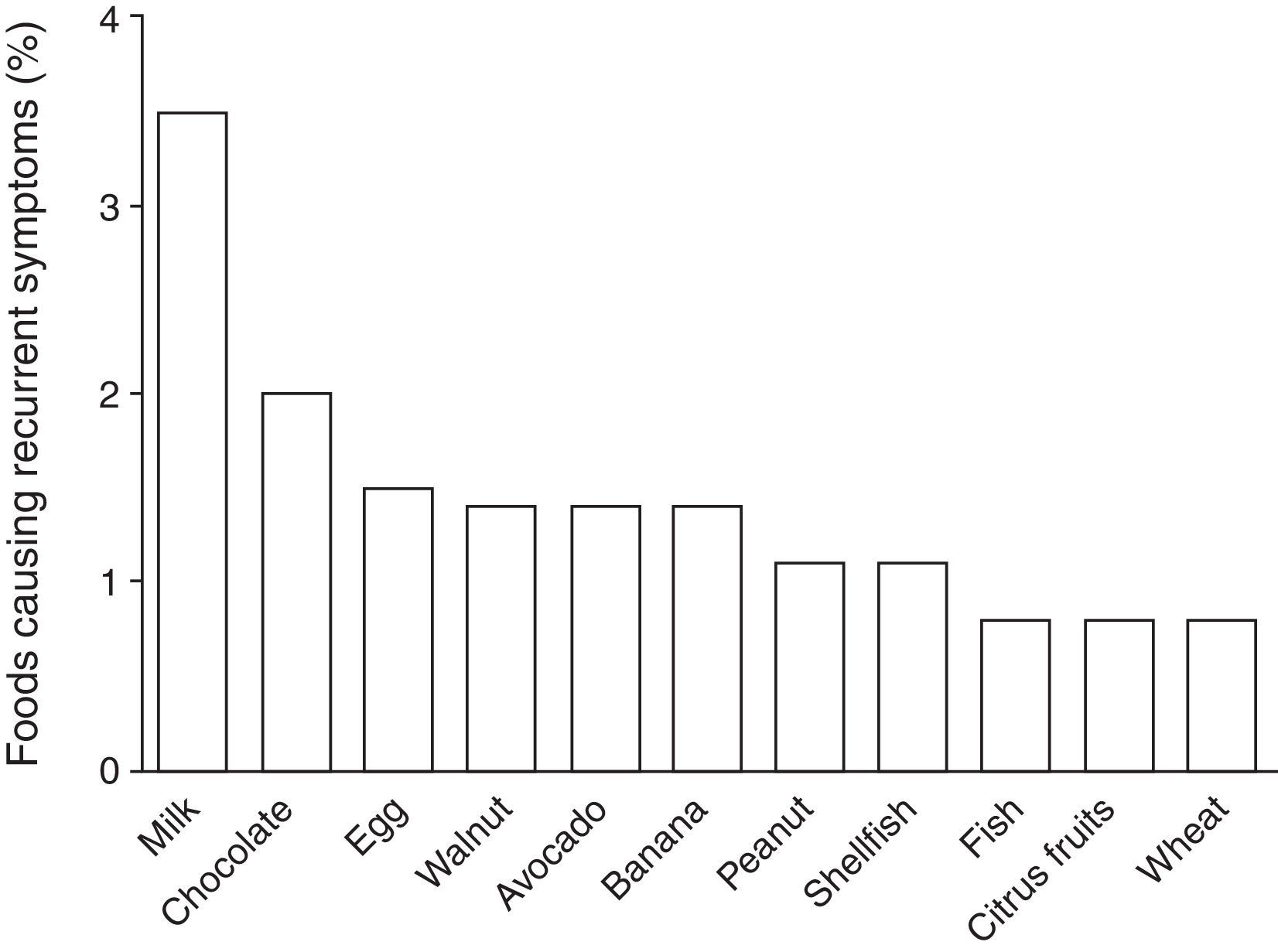

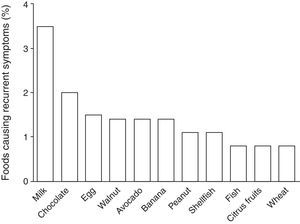

According to the parental report, 13% (n=63) of the children suffered from recurrent symptoms related to food ingestion: 41% abdominal pain, 37% hives, 16% vomiting, 13% diarrhoea, 10% swelling, 5% pruritus, and 3% trouble breathing. Among these 63 children, the foods more frequently reported by the parents as causing recurrent symptoms were: 25% milk; 14% chocolate; 11% egg; 10% walnut; 10% avocado; 10% banana; 8% peanut; 8% shellfish; 6% fish; 6% citrus fruits; and 6% wheat. Estimated prevalence rates for foods causing recurrent symptoms in Chilean school-aged children are shown in Fig. 2. Of the 63 parents who reported that their child suffered from recurrent symptoms related to food ingestion, 57% sought medical attention and 84% removed the causative food from the child's diet, but only 34% (n=22) of these children were diagnosed with FA by a physician.

After analysis of the 455 questionnaires, 43 (9%) were considered to report a possible FA either due to medical diagnosis of FA or suggestive symptoms of FA. Twenty children with recurrent symptoms related to food ingestion were excluded after the screening questionnaire because the symptoms were highly unlikely to be related to FA (e.g. headache and bloating) or due to incomplete contact information. Three children were unreachable after at least five repeated telephone calls and therefore did not answer the second questionnaire. Forty parents answered the second questionnaire. Food reactions reported by parents were not convincing of FA in 15 cases for the following reasons: headache, one; isolated vomiting, one; isolated rash delayed beyond 2h, two; isolated abdominal pain, three; convincing symptoms but only one reaction with symptoms delayed beyond 2h, two; and symptoms suggestive of lactose intolerance, five.

Twenty-five children had history of reactions that were convincing of FA resulting in a FA rate of 5.5% (95% CI, 3.6–7.9). Of these, 2% were aged 5 years, 8% were aged 10 years and 7% were aged 15 years (P<0.05). Children with FA were more frequently male than in the complete sample (68% vs. 54%), but this difference was not significant. The male predominance observed among FA cases diminished with age: 100%, 73%, and 58% in children attending kindergarten, 5th grade, and 9th grade, respectively. However, this trend was not significant (P=0.46). A total of 22 children with FA (88%) were reported by their parents to suffer from allergic diseases other than FA. These children, when compared to children without FA, were more frequently reported to have asthma (20% vs. 7%, P<0.02) and atopic dermatitis (32% vs. 13%, P<0.01), but not allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (36% vs. 25%, P=0.24). Previous studies have shown that children with FA are born more frequently in autumn/winter months than spring/summer months.14,15 In our complete sample of 455 children, no seasonal differences in month of birth were observed (autumn/winter 53%, spring/summer 47%, P=0.32). However, in children with FA, a higher, but not significant, rate was born in autumn and winter months compared to spring and summer months (64% vs. 36%, P=0.22).

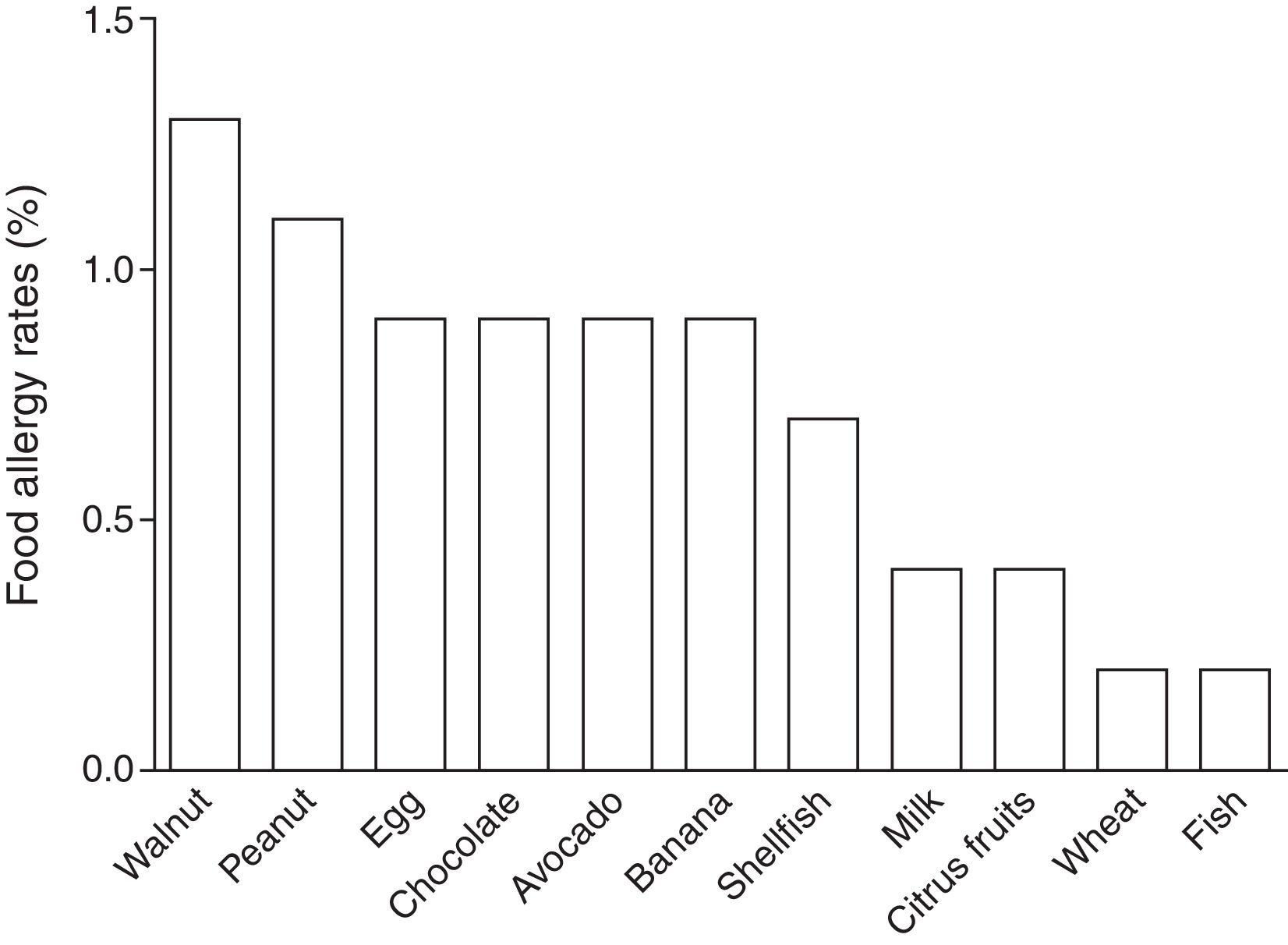

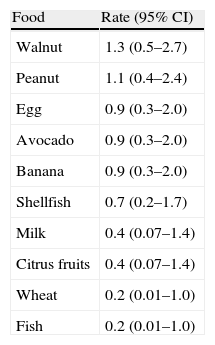

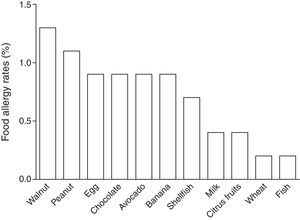

In children labelled as food allergic, the mean number of reactions in the FA cases was four (range, 1–30), 36% of the children suffered from allergy to multiple foods. Foods most frequently reported among the 25 FA cases were walnut (24%), peanut (20%), egg (16%), chocolate (16%), avocado (16%), banana (16%), and shellfish (12%). Estimated prevalence rates for FAs of Chilean school-aged children are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3.

Estimated food-specific allergy rates in Chilean school-aged children.

| Food | Rate (95% CI) |

| Walnut | 1.3 (0.5–2.7) |

| Peanut | 1.1 (0.4–2.4) |

| Egg | 0.9 (0.3–2.0) |

| Avocado | 0.9 (0.3–2.0) |

| Banana | 0.9 (0.3–2.0) |

| Shellfish | 0.7 (0.2–1.7) |

| Milk | 0.4 (0.07–1.4) |

| Citrus fruits | 0.4 (0.07–1.4) |

| Wheat | 0.2 (0.01–1.0) |

| Fish | 0.2 (0.01–1.0) |

Reported symptoms were mostly hives (60%), erythema (48%), swelling (44%), and abdominal pain (32%). Severe symptoms were rarely reported: 4% trouble breathing and 4% syncope. Eight children (32%) were admitted to the emergency department because of the FA reactions and were treated mostly with antihistamines and corticosteroids. Twelve children (48%) had episodes that by history met the definition of anaphylaxis,16 but none received epinephrine during emergency visits. A total of 13/25 parents (52%) sought outpatient medical attention because they believed their child suffered from FA. Of these, 70% were diagnosed with FA by a physician and were instructed to avoid ingestion of the causative food. However, no child was recommended to carry an epinephrine autoinjector and none of the FA children ever had an autoinjector.

DiscussionThis is the first population-based epidemiologic study to evaluate FA prevalence in Chile. We observed that about 1 in 20 school-aged Chilean children has a FA according to parental report and a detailed FA clinical questionnaire, which corresponds to an estimated 344,000 children nationwide. Our prevalence estimates are consistent with international prevalence reports that show a range of 3–35% in general population and an estimated 12% in children.6 Most studies on the epidemiology of FA have been carried out in developed countries and to the best of our knowledge, only one population-based study has previously evaluated FA in a Latin-American country.12

Risk factors of FA identified in this study were similar to that in previous reports. We observed a significant association of FA with atopic dermatitis and asthma, although we did not inquire about the sequence of onset of these diseases. Due to previous reports of an effect of season of birth on the development of FA in children, we analysed whether this was present in our sample. We observed an important, but not significant, trend of higher rate of food allergic children being born in autumn/winter compared with spring/summer seasons, similar to that reported in the United States and Australia.14,15 Further studies with a larger sample of children with FA are needed to further evaluate this finding. Younger age is usually a risk factor for immediate hypersensitivity FA.17 Surprisingly, in our study we observed a higher rate of FA in older children (i.e. 10- and 15-year-old) than in children aged five years. However, this study was not powered to evaluate prevalence in the different age groups and thus; this finding should be interpreted with caution.

FA is reported to be the main cause of anaphylaxis in childhood.18–20 In our study, about one half of the children with FA had history of reactions that were compatible with anaphylaxis. Strikingly, none of the affected children were treated with epinephrine during episodes despite the fact that 32% were admitted to an emergency department, where most received treatment with corticosteroids and/or antihistamines. Furthermore, over 50% of the FA-affected children were seen by a physician because of parental belief of FA, although most of them were diagnosed with FA, none of them were prescribed an epinephrine autoinjector or were educated in its use. Our study urgently addresses the need to educate health personnel in Chile regarding the risks of FA and the proper treatment of acute food allergic reactions.

Using a two-stage survey methodology we were able to distinguish well which foods caused recurrent symptoms in children that were likely to occur from causes different than FA (most frequently milk and chocolate), from foods that were likely culprits of immediate hypersensitivity reactions. This study found that the foods most frequently causing FA in Chilean school-children were walnut and peanut, with rates of 1.3% and 1.1% respectively. Other foods reported include common food allergens such as egg, shellfish, and fish, but also allergens less commonly reported in the literature such as avocado and banana. Allergy to peanut and walnut have been reported to be the main cause of fatal anaphylactic reactions to foods, causing 90% of demises in a US-based series of 32 cases.4 In this series, fatal reactions occurred mostly in adolescents and young adults who were known to have a prior history of FA to the food that caused the fatal reaction. In the same report it is noted that most had asthma and most did not have epinephrine available for use at the time of the reaction, two risk factors also present in our FA population. The rates of FA to peanut and walnut reported in our study closely approach the population-based prevalence rates of developed countries where these allergies constitute an important public health concern, such as the United States and Canada.11,17,21,22 These high rates are cause for serious concern, particularly when linked to the poor rates of epinephrine use in the population and local emergency departments. Thus, education on FA recognition and management is essential to improve diagnosis and treatment of this condition in Chile. This should not only be a primary concern of medical schools, but also among practicing physicians with special emphasis on emergency departments, since programmes and public policies aiming to educate clinicians and the general population about FA and anaphylaxis are currently lacking in Chile and the food industry is not compelled to warn against components that may trigger severe allergic reactions. However, recently created patient support groups together with immunologists have been actively advocating in Chilean media and government to ensure proper awareness and treatment for affected patients.

To establish the prevalence of FA in childhood is of paramount public health importance, particularly in developing countries where there are little data. However, the true prevalence of FA has been difficult to establish worldwide for multiple reasons. These include the fact that more than 170 foods have been reported to cause IgE-mediated reactions, changes in the incidence and prevalence of FA have been observed over time with a likely increase over the past decades, and that studies on FA epidemiology and natural history are difficult to compare due to study design and variations in the definition of FA.23,24 Rona et al. performed a meta-analysis on the prevalence of FA and reported a pooled overall prevalence of self-reported FA of 12% in children, a result that was far lower (3%) when symptoms of FA were accompanied by demonstration of an immune-mediated mechanism either by skin prick test, serum IgE or oral food challenge.6

The main limitation of our study is that our data are based on parental report, and were not confirmed by more specific diagnostic studies. As mentioned previously, it is widely recognised that the use of self-report to evaluate the prevalence of FA has been found to overestimate the real prevalence of the disease.6 The best way to evaluate the prevalence of FA is by designing studies that include the use of oral food challenge in subjects with probable FA, as oral food challenge has been recognised as the diagnostic gold standard in this disease.25 Nonetheless, we believe that the use of a two-stage methodology with questionnaires previously used in other large studies and a clear definition of “convincing” food-related allergic reaction, allowed us to obtain a conservative and more accurate estimate of FA prevalence in Chilean school-aged children. FA questionnaire responses may be affected by additional sources of bias such as recall bias and non-response bias. Although it is impossible to completely control recall bias when assessing history of food allergic reactions, the use of a systematic extended questionnaire by telephone interview should reduce its effect. Another limitation of our study was that it included only private schools of Santiago, although geographically representative of neighbourhoods with different socioeconomic status. Due to a prolonged strike in the Chilean public school system during the study period, inclusion of public schools was not possible. One of the strengths of our study is the high response rate and low loss to follow-up rates, minimising possible non-response bias.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to report the prevalence of FA in Chile. We observed that peanut and walnut are currently the main causative foods involved in FA, approaching rates similar to those of developed countries. Education regarding the proper recognition and management of acute food-induced allergic reactions in healthcare personnel and the general population seems urgent, given the results of this study.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

FundingThis work was funded by an intramural grant of the Division of Pediatrics of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile School of Medicine.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest regarding this study.

We would like to thank Dr. Scott Sicherer for kindly providing a previously reported food allergy survey questionnaire.