Elder abuse, an important human rights issue and public health problem, contributes to increased disability and mortality. In the last decades, several reviews have synthesized primary studies to determine its prevalence. This umbrella review aimed to estimate the worldwide overall prevalence rate of elder abuse in the community and care setting.

MethodsFollowing prospective registration at PROSPERO (CRD42021281866) we conducted a search of eight electronic databases to identify systematic reviews from inception until 17 January 2023. The corrected covered area was calculated to estimate the potential overlap of primary studies between reviews. The quality of the selected reviews was assessed using a modified AMSTAR-2 instrument. We extracted data on the prevalence of any type of elder (people aged 60 years old or older) abuse in the community and care setting.

ResultsThere were 16 systematic reviews retrieved between 2007 and 2022, out of which ten captured prevalence globally, three in Iran, one in Turkey, one in China and one in Brazil. The 16 reviews included 136 primary studies in total between 1988 and 2020. The overlapping of studies between reviews was found to be moderate (5.5%). The quality of reviews was low (2, 12.5%) or critically low (14, 87.5%). The estimated range of global prevalence of overall elder abuse was wide (1.1–78%), while the estimations of specific abuse prevalence ranged from 0–81.8% for neglect, 1.1–78.9% for psychological abuse, 0.7–78.3% for financial abuse, 0.1–67.7% for physical abuse, and 0–59.2% for sexual abuse.

ConclusionsAlthough the low quality of the evidence and the heterogeneity of the phenomenon makes it hard to give precise prevalence data, it is without a question that elder abuse is a prevalent problem with a wide dispersion. The focus of attention should shift towards interventions and policymaking to prevent this form of abuse.

El abuso de personas mayores, una cuestión importante de derechos humanos y un problema de salud pública, contribuye a aumentar la discapacidad y la mortalidad. En las últimas décadas, varias revisiones sistemáticas han sintetizado estudios primarios para determinar su prevalencia. El objetivo de esta revisión paraguas fue estimar la tasa de prevalencia mundial del abuso de personas mayores en los ámbitos comunitario y de cuidados.

MetodologíaTras el registro prospectivo en PROSPERO (CRD42021281866), llevamos a cabo una búsqueda en 8 bases de datos electrónicas para identificar revisiones sistemáticas desde el inicio hasta el 17 de enero de 2023. Se calculó el área cubierta corregida para estimar el posible solapamiento de estudios primarios entre las revisiones sistemáticas incluidas. La calidad de las revisiones seleccionadas fue evaluada con una versión modificada del instrumento AMSTAR-2. Se extrajeron datos de prevalencia de cualquier tipo de abuso de mayores (personas de 60 o más años) en los ámbitos comunitario y de cuidados.

ResultadosSe identificaron 16 revisiones sistemáticas entre 2007 y 2022, de las cuales 10 estimaron la prevalencia a nivel mundial, 3 en Irán, una en Turquía, otra en China y una última en Brasil. Estas 16 revisiones incluían 136 estudios primarios entre 1988 y 2020. El solapamiento de estudios primarios entre revisiones sistemáticas fue moderado (5,5%). La calidad de las revisiones fue baja (2; 12,5%) o críticamente baja (14; 87,5%). El rango estimado de prevalencia global de abuso en general de personas mayores fue amplio (1,1-78%). El rango estimado de abuso específico osciló entre el 0-81,8% para negligencia, el 1,1-78,9% para abuso psicológico, el 0,7-78,3% para abuso económico, el 0,1-67,7% para abuso físico, y el 0-59,2% para abuso sexual.

ConclusionesAunque la baja calidad de la evidencia y la heterogeneidad del fenómeno dificulta proporcionar un valor de prevalencia preciso, el abuso de personas mayores es un problema prevalente con una amplia dispersión. La atención debe centrarse en las intervenciones y la formulación de políticas para prevenir esta forma de maltrato.

Elder abuse (EA), a single or repeated act including lack of appropriate action occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust and causing harm or distress to an older person,1 is often classified as neglect, psychological, financial, physical, or sexual abuse among other forms.2,3 The elderly are often more susceptible to harm due to their inherent human vulnerability, which is more likely to manifest with advancing age.4,5 Frailty is an age-related clinical state that results from the higher likelihood of developing adverse health-related outcomes under exposure to a stressor that in younger counterparts would be easily tolerated.5,6 Estimates suggest that at a global level, one in six older people is affected by abuse (pooled prevalence of 15.7% according to a large-scale meta-analysis),3 and it is related to higher levels of depression,7–9 suicidal ideation,9 anxiety disorders,8 post-traumatic stress disorder,8 sleep disturbances,9 chronic pain,9 metabolic syndrome9 and poor general health.8,9 There is more frequent hospitalization,10–12 nursing home placement,12 and increased disability and mortality9,13 among older adults who suffer abuse. Furthermore, according to the available data, in the institutional setting, the estimate of the overall abuse rate self-reported by staff was 64.2%.14 Despite the associated health impact, the problem often goes unrecognized with little awareness,15,16 and health care professionals report a lack of training and knowledge on the matter.16 A qualitative study showed that a large percentage of health care professional students did not perceive all subtypes as a case of abuse.15

Several systematic reviews have attempted to estimate the worldwide prevalence of EA, but a PubMed search for reviews of the topic in January 2023 did not reveal any overview of reviews published to synthesize all relevant studies. Overviews of reviews, also known as umbrella reviews, are essential tools in evidence synthesis, making it possible to determine if the findings of systematic reviews on a certain topic are consistent or contradictory, by providing a broader picture of the topic.17 Such an umbrella review on the prevalence of EA could give us a better understanding of the magnitude of and the variation in the global health burden of the problem to help policymakers.

This umbrella review aimed to estimate the worldwide overall prevalence rate of EA in community and care settings. As an additional objective, we aimed to stratify the estimation according to the type of abuse.

MethodsThe umbrella review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021281866), and written to meet the guidance covered in the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) statement18 (Appendix A).

Search strategy and study selectionA systematic search was conducted in eight bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collections, Scopus, CINAHL, APA PsycINFO, Social Science Database, Sociological Abstracts and Cochrane Library) looking for citations of systematic reviews on the prevalence of EA from inception until 17 January 2023, without language restriction.19 The keyword combination used in our search queries captured the concept ‘EA AND Prevalence AND Systematic Review’. The detailed search strategies with all the database-specific strings are available in Appendix B.

We included studies that met the following criteria: (i) systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis searching at least two databases electronically20 and (ii) measurement of the prevalence of any form of EA in the community or care setting. We considered systematic reviews if they applied rigorous, reproducible scientific methodology to avoid bias and critically appraised the quality of primary studies.18,21 We defined elderly people by the United Nations (UN) definition, as those with age equal to or greater than 60 years,22 and EA using the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO)1 operationalized by Yon et al. in their systematic review,3 excluding studies that only focused on homicide or self-neglect. Studies that included other age groups as well, but reported EA for people aged 60 years or older separately, were included. Systematic reviews that had extractable data of a subgroup of elderly people (e.g. people living with disability or dementia) were included but reported separately. Studies where the existence of a relation of trust between victim and perpetrator was not unambiguous (e.g. resident-to-resident abuse in long-term homes) and studies on abuse committed by strangers were excluded for not meeting the WHO definition.1 Primary studies and narrative reviews were excluded, too.

For the screening of citations, we used Rayyan, an open-source artificial intelligence-assisted systematic literature review tool.23,24 After the deduplication of the records, two reviewers (JMTJ and BJ) independently screened the titles and abstracts looking for relevant citations. When the review team lacked working proficiency in the language of an article, the article was translated with the help of a native speaker aided by Google Translate, as it has been demonstrated to be a viable strategy to avoid language bias.25 The full-text versions of the shortlisted citations were obtained and read thoroughly to determine study eligibility. Those not meeting the inclusion criteria were removed. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved with consensus and arbitration involving a third reviewer (ABC, NCI or KSK). Where full-texts were unavailable we attempted to contact authors via e-mail or ResearchGate to obtain full-texts. If author contact was not found, authors did not reply, or were not able to provide a full-text article, the record was excluded as “not available”. Before submission for publication, The Retraction Watch Database was checked to make sure none of the included reviews were subject to retraction (03 November 2023).26

Data extractionData were extracted from the selected systematic reviews by two reviewers. One reviewer (BJ) extracted the data to an MS Excel sheet, and the second reviewer (JMTJ) checked all the extracted data identifying possible errors. Extracted data included the name of the first author and publication time, the covered time interval by the primary studies, geographical location of included primary studies, number of included primary studies, type of included primary studies, if EA was the main outcome, if EA was institutional or based in the community setting, type of violence, if the authors performed a meta-analysis, and data on the prevalence of EA. The reporting of abuse subtypes was especially important, as evidence suggests that the related factors could be different for each.27 Although this research aimed to review the systematic reviews, not the primary studies, data extraction did not consist of only copying the results, but rather examining them critically, excluding results of primary studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria (e.g.: people aged younger than 60 years, not meeting our criteria of EA, etc.). As the number of included studies, we reported the ones that data were extracted from. During data extraction, verbal, psychological and emotional abuse was treated synonymously, as well as financial and economic. Where possible, data on these subtypes were homogenized for easier comprehension of the results, except for pooled data, where it was not possible.

Quality assessmentTwo reviewers (JMTJ and BJ) separately assessed the quality of the systematic reviews including the risk of bias (RoB) using a modified AMSTAR-2 tool.28 Modification or omission of subitems was necessary when the subitem was specific for clinical trials. For the modification, we sought input from other published instruments of prevalence studies29 and our previous umbrella review of prevalence.30 Any discrepancy between the two reviewers during the critical appraisal process was resolved with the help of a third reviewer (NCI). Overall quality was assessed on the lines suggested in the original AMSTAR-2 tool.28 Items number 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15 were considered critical points. The overall confidence in the results of the included systematic reviews was classified as high (no or one non-critical weakness), moderate (more than one non-critical weakness), low (one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses) or critically low (more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses). An overall score was not calculated. The modified checklist is available in Appendix C.

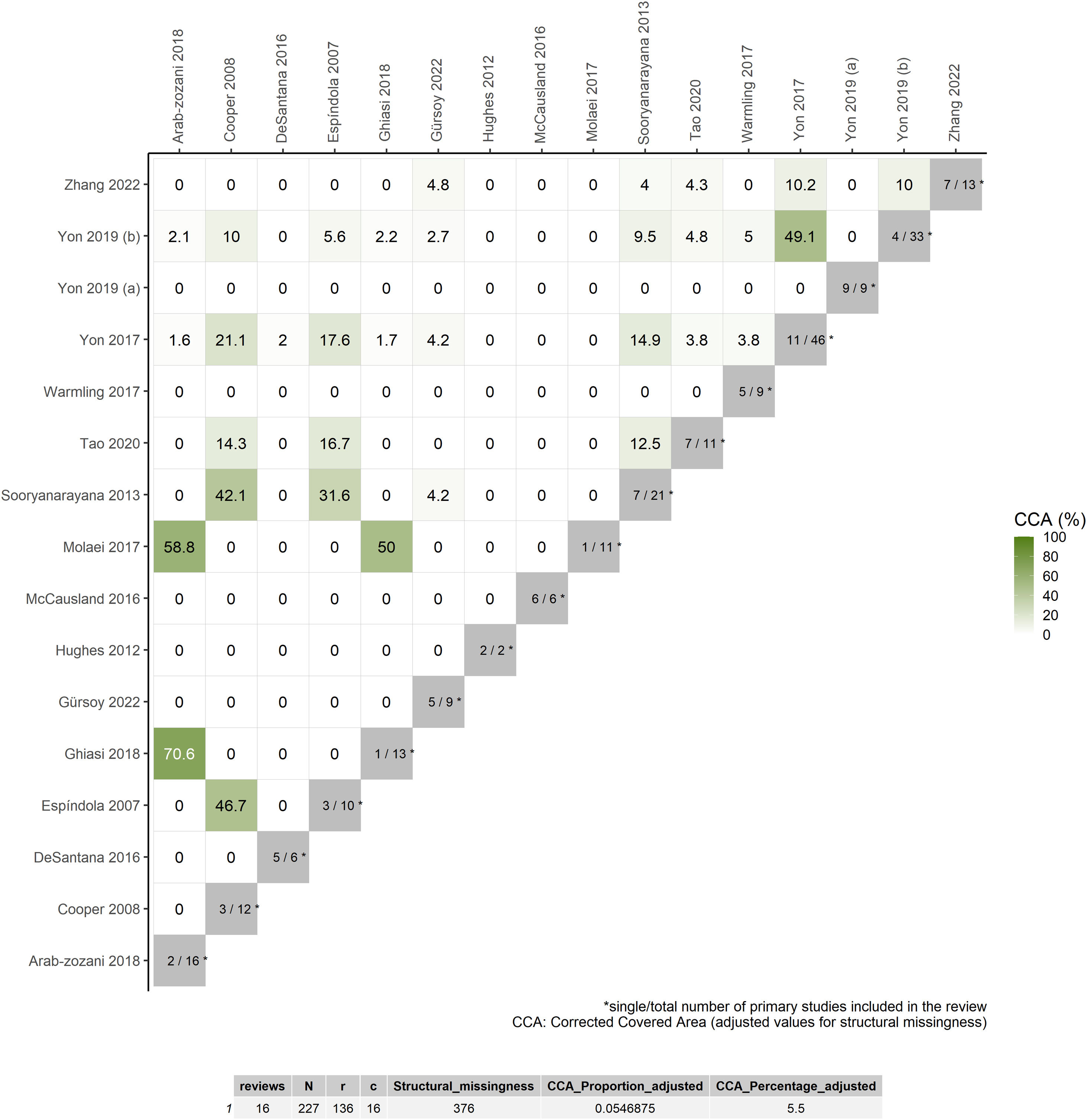

Data synthesisResults obtained from data extraction were summarized in a table format and narratively. To evaluate the potential overlap of primary studies, a matrix of primary study coverage was created in MS Excel. The corrected covered area (CCA) adjusted for structural missingness was estimated by using R Studio and the results were represented in a heatmap.31 The degree of overlapping was categorized into four categories: very high (CCA >15%), high (CCA 11–15%), moderate (CCA 6–10%), and slight (CCA 0–5%).18

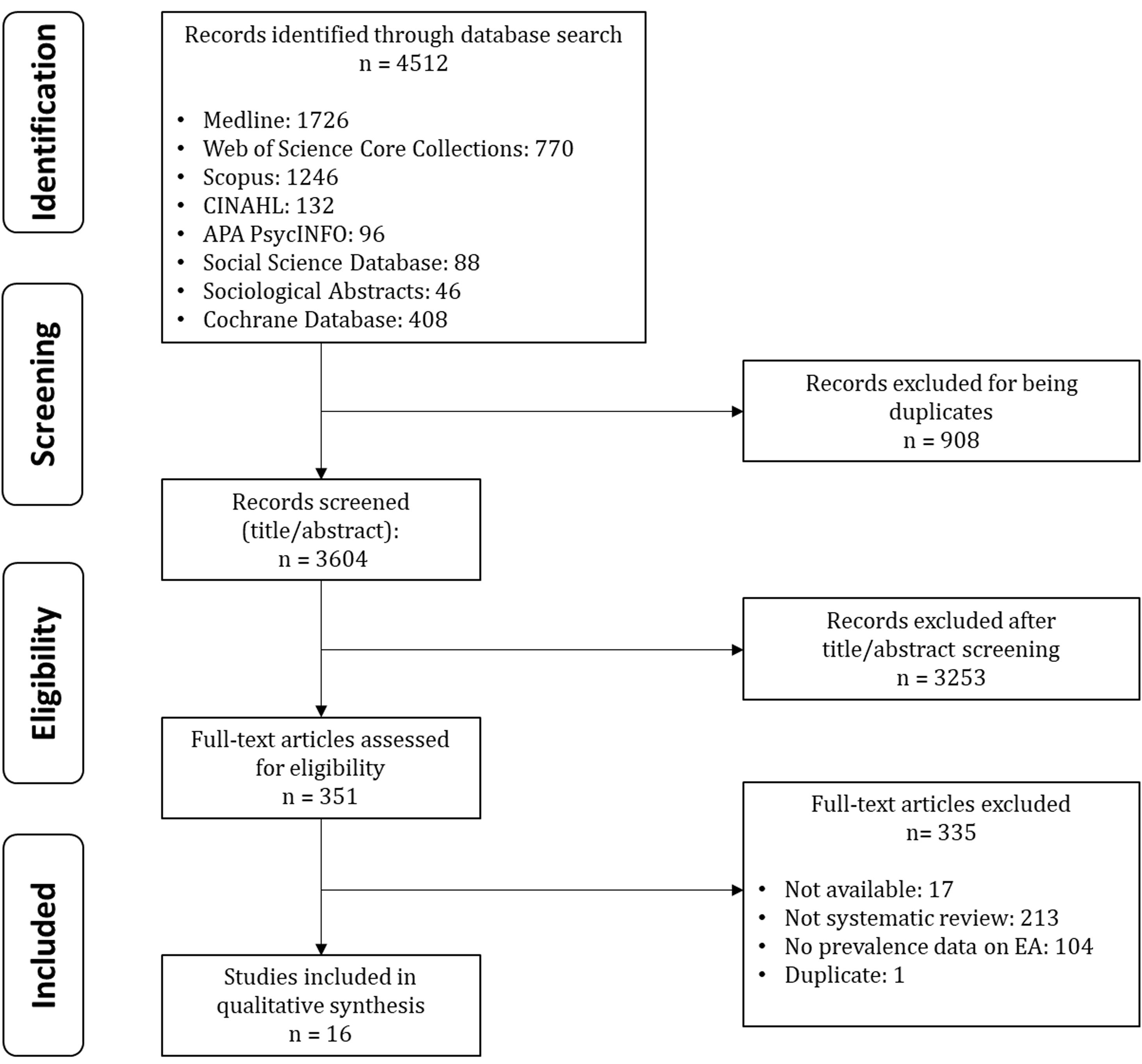

ResultsStudy selectionThere were 4512 citations from eight electronic databases, from which 908 were excluded for being a duplicate record, 3253 were excluded after the title and abstract reading and 335 were excluded after full-text reading. The flowchart of the study selection is shown in Fig. 1. The list of excluded full-text articles and a brief explanation for the exclusion is provided in Appendix D.

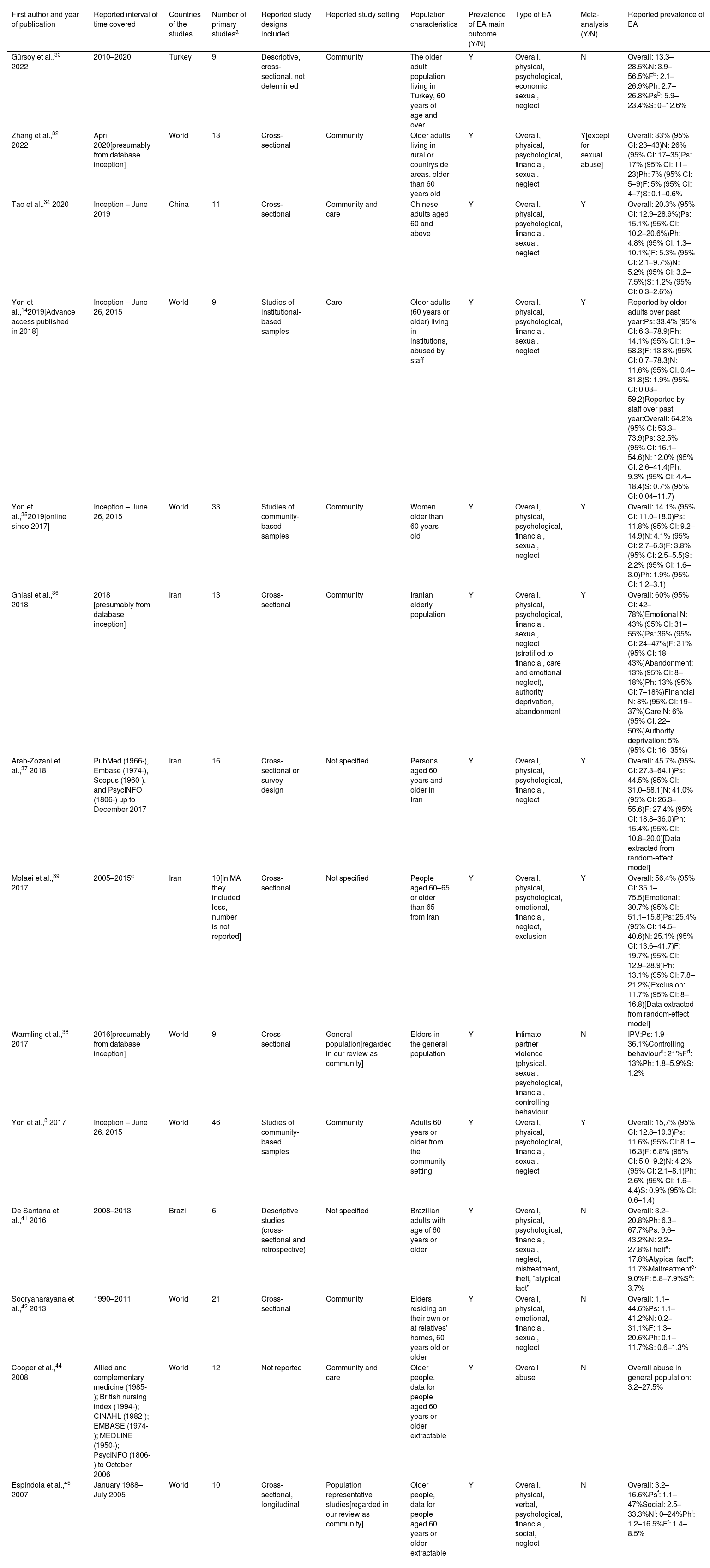

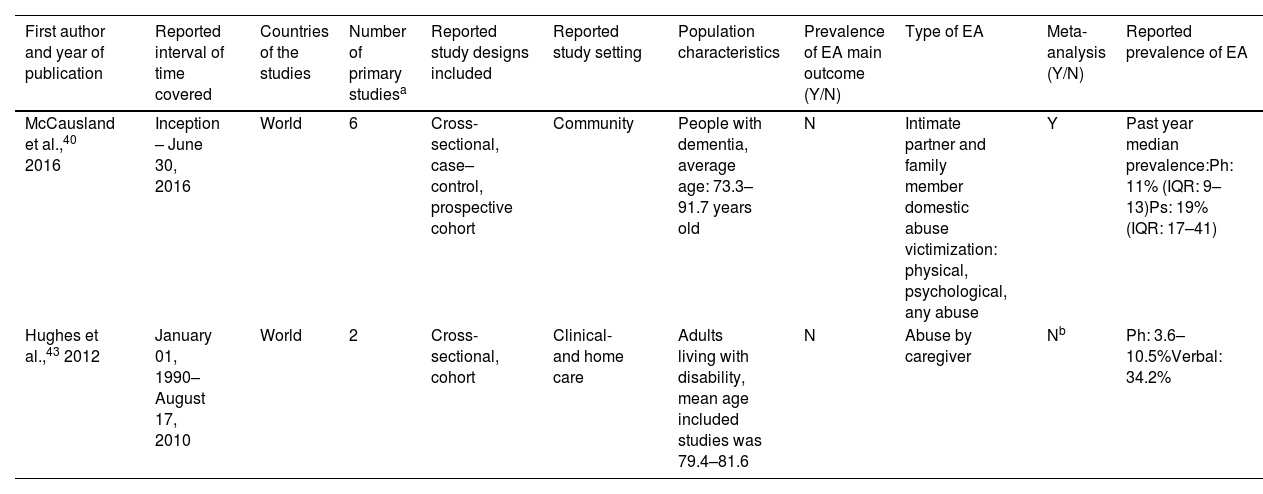

We identified and included 16 systematic reviews3,14,32–45 for the synthesis and critical appraisal, of which two reported data in specific subpopulations (elders living with disabilities43 and with dementia,40 respectively). The reviews were all published in peer-reviewed academic journals between 2007 and 2022. Ten systematic reviews aimed to capture prevalence estimates globally,3,14,32,35,38,40,42–45 three in Iran,36,37,39 one in Turkey,33 one in China34 and one in Brasil.41 Nine systematic reviews reported EA only in community setting,3,32,33,35,36,38,40,42,45 two only in care setting,14,43 two in both,34,44 and three did not report the setting of abuse.37,39,41 One study focused on elderly women,35 and one on intimate partner violence.38 Nine reviews performed meta-analysis for the prevalence of elderly abuse.3,14,32,34–37,39,40 Extracted data were from 136 primary studies published between 1988 and 2020. The results of data extraction are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Characteristics of systematic reviews on the prevalence of elder abuse (EA).

| First author and year of publication | Reported interval of time covered | Countries of the studies | Number of primary studiesa | Reported study designs included | Reported study setting | Population characteristics | Prevalence of EA main outcome (Y/N) | Type of EA | Meta-analysis (Y/N) | Reported prevalence of EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gürsoy et al.,33 2022 | 2010–2020 | Turkey | 9 | Descriptive, cross-sectional, not determined | Community | The older adult population living in Turkey, 60 years of age and over | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, economic, sexual, neglect | N | Overall: 13.3–28.5%N: 3.9–56.5%Fb: 2.1–26.9%Ph: 2.7–26.8%Psb: 5.9–23.4%S: 0–12.6% |

| Zhang et al.,32 2022 | April 2020[presumably from database inception] | World | 13 | Cross-sectional | Community | Older adults living in rural or countryside areas, older than 60 years old | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect | Y[except for sexual abuse] | Overall: 33% (95% CI: 23–43)N: 26% (95% CI: 17–35)Ps: 17% (95% CI: 11–23)Ph: 7% (95% CI: 5–9)F: 5% (95% CI: 4–7)S: 0.1–0.6% |

| Tao et al.,34 2020 | Inception – June 2019 | China | 11 | Cross-sectional | Community and care | Chinese adults aged 60 and above | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect | Y | Overall: 20.3% (95% CI: 12.9–28.9%)Ps: 15.1% (95% CI: 10.2–20.6%)Ph: 4.8% (95% CI: 1.3–10.1%)F: 5.3% (95% CI: 2.1–9.7%)N: 5.2% (95% CI: 3.2–7.5%)S: 1.2% (95% CI: 0.3–2.6%) |

| Yon et al.,142019[Advance access published in 2018] | Inception – June 26, 2015 | World | 9 | Studies of institutional-based samples | Care | Older adults (60 years or older) living in institutions, abused by staff | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect | Y | Reported by older adults over past year:Ps: 33.4% (95% CI: 6.3–78.9)Ph: 14.1% (95% CI: 1.9–58.3)F: 13.8% (95% CI: 0.7–78.3)N: 11.6% (95% CI: 0.4–81.8)S: 1.9% (95% CI: 0.03–59.2)Reported by staff over past year:Overall: 64.2% (95% CI: 53.3–73.9)Ps: 32.5% (95% CI: 16.1–54.6)N: 12.0% (95% CI: 2.6–41.4)Ph: 9.3% (95% CI: 4.4–18.4)S: 0.7% (95% CI: 0.04–11.7) |

| Yon et al.,352019[online since 2017] | Inception – June 26, 2015 | World | 33 | Studies of community-based samples | Community | Women older than 60 years old | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect | Y | Overall: 14.1% (95% CI: 11.0–18.0)Ps: 11.8% (95% CI: 9.2–14.9)N: 4.1% (95% CI: 2.7–6.3)F: 3.8% (95% CI: 2.5–5.5)S: 2.2% (95% CI: 1.6–3.0)Ph: 1.9% (95% CI: 1.2–3.1) |

| Ghiasi et al.,36 2018 | 2018 [presumably from database inception] | Iran | 13 | Cross-sectional | Community | Iranian elderly population | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect (stratified to financial, care and emotional neglect), authority deprivation, abandonment | Y | Overall: 60% (95% CI: 42–78%)Emotional N: 43% (95% CI: 31–55%)Ps: 36% (95% CI: 24–47%)F: 31% (95% CI: 18–43%)Abandonment: 13% (95% CI: 8–18%)Ph: 13% (95% CI: 7–18%)Financial N: 8% (95% CI: 19–37%)Care N: 6% (95% CI: 22–50%)Authority deprivation: 5% (95% CI: 16–35%) |

| Arab-Zozani et al.,37 2018 | PubMed (1966-), Embase (1974-), Scopus (1960-), and PsycINFO (1806-) up to December 2017 | Iran | 16 | Cross-sectional or survey design | Not specified | Persons aged 60 years and older in Iran | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, neglect | Y | Overall: 45.7% (95% CI: 27.3–64.1)Ps: 44.5% (95% CI: 31.0–58.1)N: 41.0% (95% CI: 26.3–55.6)F: 27.4% (95% CI: 18.8–36.0)Ph: 15.4% (95% CI: 10.8–20.0)[Data extracted from random-effect model] |

| Molaei et al.,39 2017 | 2005–2015c | Iran | 10[In MA they included less, number is not reported] | Cross-sectional | Not specified | People aged 60–65 or older than 65 from Iran | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, emotional, financial, neglect, exclusion | Y | Overall: 56.4% (95% CI: 35.1–75.5)Emotional: 30.7% (95% CI: 51.1–15.8)Ps: 25.4% (95% CI: 14.5–40.6)N: 25.1% (95% CI: 13.6–41.7)F: 19.7% (95% CI: 12.9–28.9)Ph: 13.1% (95% CI: 7.8–21.2%)Exclusion: 11.7% (95% CI: 8–16.8)[Data extracted from random-effect model] |

| Warmling et al.,38 2017 | 2016[presumably from database inception] | World | 9 | Cross-sectional | General population[regarded in our review as community] | Elders in the general population | Y | Intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, psychological, financial, controlling behaviour | N | IPV:Ps: 1.9–36.1%Controlling behaviourd: 21%Fd: 13%Ph: 1.8–5.9%S: 1.2% |

| Yon et al.,3 2017 | Inception – June 26, 2015 | World | 46 | Studies of community-based samples | Community | Adults 60 years or older from the community setting | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect | Y | Overall: 15,7% (95% CI: 12.8–19.3)Ps: 11.6% (95% CI: 8.1–16.3)F: 6.8% (95% CI: 5.0–9.2)N: 4.2% (95% CI: 2.1–8.1)Ph: 2.6% (95% CI: 1.6–4.4)S: 0.9% (95% CI: 0.6–1.4) |

| De Santana et al.,41 2016 | 2008–2013 | Brazil | 6 | Descriptive studies (cross-sectional and retrospective) | Not specified | Brazilian adults with age of 60 years or older | Y | Overall, physical, psychological, financial, sexual, neglect, mistreatment, theft, “atypical fact” | N | Overall: 3.2–20.8%Ph: 6.3–67.7%Ps: 9.6–43.2%N: 2.2–27.8%Thefte: 17.8%Atypical facte: 11.7%Maltreatmente: 9.0%F: 5.8–7.9%Se: 3.7% |

| Sooryanarayana et al.,42 2013 | 1990–2011 | World | 21 | Cross-sectional | Community | Elders residing on their own or at relatives’ homes, 60 years old or older | Y | Overall, physical, emotional, financial, sexual, neglect | N | Overall: 1.1–44.6%Ps: 1.1–41.2%N: 0.2–31.1%F: 1.3–20.6%Ph: 0.1–11.7%S: 0.6–1.3% |

| Cooper et al.,44 2008 | Allied and complementary medicine (1985-); British nursing index (1994-); CINAHL (1982-); EMBASE (1974-); MEDLINE (1950-); PsycINFO (1806-) to October 2006 | World | 12 | Not reported | Community and care | Older people, data for people aged 60 years or older extractable | Y | Overall abuse | N | Overall abuse in general population: 3.2–27.5% |

| Espíndola et al.,45 2007 | January 1988–July 2005 | World | 10 | Cross-sectional, longitudinal | Population representative studies[regarded in our review as community] | Older people, data for people aged 60 years or older extractable | Y | Overall, physical, verbal, psychological, financial, social, neglect | N | Overall: 3.2–16.6%Psf: 1.1–47%Social: 2.5–33.3%Nf: 0–24%Phf: 1.2–16.5%Ff: 1.4–8.5% |

Abbreviations: Y: yes, N: no, N: neglect, F: financial abuse, Ph: physical abuse, S: sexual abuse, Ps: psychological abuse, S: sexual abuse, MA: meta-analysis, IPV: intimate partner violence.

We observed a discrepancy in the reported data. In the manuscript (“Abstract and Results” section) the reported prevalence of F is 26.9% and of Ps is 23.4%. In Table 1 one primary study is shown where the reported prevalence of F is 27.9% and of Ps is 57.4%. No justification for the discrepancy is provided. In our review, we report the lower data in both cases.

We observed a discrepancy in the reported timeframe of the literature search. In the abstract of the manuscript they report 2005–2014, but in the “Methods” section they report 2005–2015.

Data on controlling behaviour and financial abuse is based on one study that reports prevalence of IPV among women aged 66–86 years old.

We observed a discrepancy and inclarity in the reported data. In the manuscript they report Ps: 47%, Ph: 16.5% and F: 8.5% as the maximum observed prevalence data. In the table they only report it as stratified for sex (among men Ps: 49%, Ph: 15%, F: 8%; among women Ps: 46%, Ph: 18%, F: 9%). In the abstract they report Ph: 18%. Reported minimum value for N (0%) only included women. Reported minimum value for both sexes was 0.2%.

Characteristics of systematic reviews on the prevalence of elder abuse (EA) among special subpopulations of elderly.

| First author and year of publication | Reported interval of time covered | Countries of the studies | Number of primary studiesa | Reported study designs included | Reported study setting | Population characteristics | Prevalence of EA main outcome (Y/N) | Type of EA | Meta-analysis (Y/N) | Reported prevalence of EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCausland et al.,40 2016 | Inception – June 30, 2016 | World | 6 | Cross-sectional, case–control, prospective cohort | Community | People with dementia, average age: 73.3–91.7 years old | N | Intimate partner and family member domestic abuse victimization: physical, psychological, any abuse | Y | Past year median prevalence:Ph: 11% (IQR: 9–13)Ps: 19% (IQR: 17–41) |

| Hughes et al.,43 2012 | January 01, 1990–August 17, 2010 | World | 2 | Cross-sectional, cohort | Clinical- and home care | Adults living with disability, mean age included studies was 79.4–81.6 | N | Abuse by caregiver | Nb | Ph: 3.6–10.5%Verbal: 34.2% |

Abbreviations: Y: yes, N: no, Ph: physical abuse, Ps: psychological abuse.

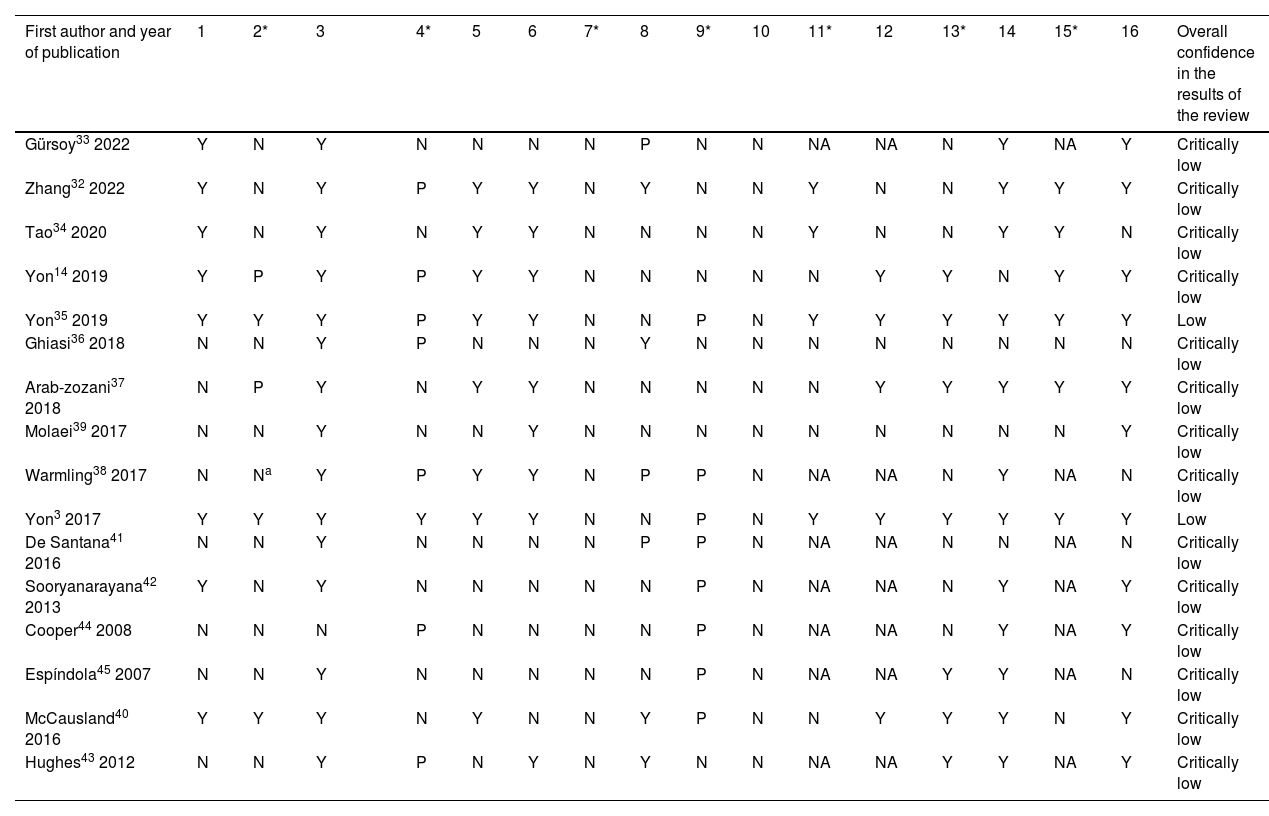

The results of the quality appraisal with the modified AMSTAR-2 checklist are shown in Table 3. Out of the 16 included studies, two reached results with low, and 14 with critically low confidence. A common critical flaw was item 7: none of the review authors provided a list of all potentially relevant studies that were read in full-text form but excluded from the review. Regarding the other critical points, item 2 (prospective registration) was met partially or completely by 31.3% of the reviews, item 4 (comprehensive literature search) by 50%, item 9 (a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias) by 50%, item 11 (justification of performing meta-analysis) by 44.4%, item 13 (accounting for RoB in individual studies) by 43.8%, and item 15 (adequate investigation of publication bias) by 66.7%. Out of the non-critical items a common flaw was item 10: none of the review authors reported on the sources of funding for the included primary studies.

Quality assessment of systematic reviews on the prevalence of elder abuse (EA) deploying critical appraisal with modified AMSTAR-2 instrument.

| First author and year of publication | 1 | 2* | 3 | 4* | 5 | 6 | 7* | 8 | 9* | 10 | 11* | 12 | 13* | 14 | 15* | 16 | Overall confidence in the results of the review | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gürsoy33 2022 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | P | N | N | NA | NA | N | Y | NA | Y | Critically low | |

| Zhang32 2022 | Y | N | Y | P | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Critically low | |

| Tao34 2020 | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Critically low | |

| Yon14 2019 | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Critically low | |

| Yon35 2019 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | N | N | P | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low | |

| Ghiasi36 2018 | N | N | Y | P | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Critically low | |

| Arab-zozani37 2018 | N | P | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Critically low | |

| Molaei39 2017 | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Critically low | |

| Warmling38 2017 | N | Na | Y | P | Y | Y | N | P | P | N | NA | NA | N | Y | NA | N | Critically low | |

| Yon3 2017 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | P | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low | |

| De Santana41 2016 | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | P | P | N | NA | NA | N | N | NA | N | Critically low | |

| Sooryanarayana42 2013 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | P | N | NA | NA | N | Y | NA | Y | Critically low | |

| Cooper44 2008 | N | N | N | P | N | N | N | N | P | N | NA | NA | N | Y | NA | Y | Critically low | |

| Espíndola45 2007 | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | P | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | N | Critically low | |

| McCausland40 2016 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | P | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Critically low | |

| Hughes43 2012 | N | N | Y | P | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | Y | Critically low |

Abbreviations: Y: yes, N: no, P: partially yes, NA: does not apply (no meta-analysis was conducted), *: critical domains. Domains of modified AMSTAR-2: 1. Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the relevant components (Population, Exposure, Outcome)? 2. Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol? 3. Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review? 4. Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? 5. Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? 6. Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? 7. Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? 8. Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail? 9. Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review? 10. Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review? 11. If meta-analysis was performed did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? 12. If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis? 13. Did the review authors account for RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review? 14. Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review? 15. If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review? 16. Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review? The complete modified checklist with detailed subitems is available in Appendix C.

The calculation of CCA is shown in Appendix E. The heatmap showing CCA adjusted for structural missingness is shown in Fig. 2. Overall overlapping was moderate (5.5%). The highest degrees of overlapping were found between the reviews of EA in Iran.36,37,39 The two reviews covering subpopulations of the elderly40,43 had no overlapping studies with other reviews.

Prevalence of elder abuseThe range of reported prevalence data of overall abuse at a global level regardless of setting was between 1.1 and 78%.36,42 Abuse in the community setting was reported between 1.1 and 78%,36,42 while institutional abuse (reported by staff) had an overall rate of 53.3–73.9%.14 Studies that obtained the best results with AMSTAR estimated the prevalence of overall abuse in the community setting as 15.7% (95% CI: 12.8–19.3) in the general population3 and as 14.1% (95% CI: 11.0–18.0) among elderly women.35

Most authors used neglect, psychological- (or verbal- or emotional-), physical-, financial- (or economic-) and sexual abuse as main subcategories. Some authors divided neglect into subtypes as well36 or used other categories such as exclusion,39 theft, maltreatment, atypical fact,41 social abuse45 or controlling behaviour in the context of intimate partner violence.38 Comparing the commonly used subtypes, generally higher ranges were shown for psychological abuse3,14,32–37,39,41,42,45 and neglect,32,33,37 while except for one review on the abuse of elderly women,35 sexual abuse was estimated as the least common subtype. The reported range of neglect was 0–81.8%,14,45 of psychological abuse 1.1–78.9%,14,42,45 of financial abuse 0.7–78.3%,14 of physical abuse 0.1–67.7%,41,42 and of sexual abuse 0–59.2%.14,33

Reviews often reported heterogeneity and broad ranges of prevalence data.3,14,32,35,37,42,44 The common explications for the source of heterogeneity were differences between sample sizes,3,37 sampling methods,32,37,40 data collection methods and instruments,3,32,33,36,37,40,42,44,45 definitions of elder abuse,32,36 and cultural or socioeconomic contexts.3,32–34,36,37,45 There were differences observed in the prevalence measure period, for example, Yon et al.3 reported that out of the 234 studies included in their systematic review, 84 reported a period ranging from one month to 5-years or did not report the prevalence period at all. Meta-regressions revealed potential association between abuse and sample size,3,35 countries’ income level classification,3,35 methods of data collection,3 and WHO regions.35

While some authors reported higher prevalence rates in Asia and Africa,35,42,45 Tao et al. got to the conclusion that elder abuse is less prevalent in China.34 Estimates in Iran were generally higher than the global estimates.36,37,39 Review authors advised caution with self-reported estimates, as they do not indicate the overall prevalence rate,14 can be subjective, susceptible for memory bias, influenced by fear or inhibition, and potentially overevaluate.45 On the other hand, other authors interpreted their findings as potentially underestimating the real value.35,43,44

Regarding the geographical dispersion of EA, Warmling et al.38 reported that most of the included primary studies were from Europe or the United States of America, which is consistent with the findings of Yon et al.,3 that robust studies were scarce in low and middle-income countries. Studies on the prevalence of abuse of elderly women were also found absent in South-Eastern Asia and Africa.35 There was also a reported lack of primary studies in institutional settings, especially in middle- and low-income countries.14

DiscussionOur umbrella review covered 16 systematic reviews and drew data from 136 primary studies to synthesize scientific evidence. We chose this method, as various systematic reviews had already been published, but no overview consolidated the findings of these. This umbrella review on the prevalence of EA is the first of its kind, prospectively registered and reported using a checklist.28 Overviews of reviews are often considered as the highest level of scientific evidence,46 thus filling in an important research gap. The reviews were largely of low quality. EA was a prevalent problem (1.1–78%), with a wide dispersion on a global level, both in the community and care setting. A large difference was observed between the prevalence of the different subtypes.

As this is the first umbrella review of the prevalence of EA, it is not possible to compare our results with measures obtained by the same research design. When comparing with previous studies, it is natural that our reported prevalence range is wider, as our estimate includes all the extreme values reported by any previous systematic reviews (and primary studies indirectly). Prevalence ranges reported by previous studies, such as the commonly cited values of Yon et al. (15.7%, 95% CI: 12.8–19.3)3 are covered in our overall range. Greater precision in findings can be achieved with meta-analysis, but this technique is not so far developed for umbrella reviews. The added value of our work is that it provides a broader picture of the phenomenon. An important aim of overviews is to determine if systematic reviews come to the same or contradictory conclusions. Thus, to interpret our results, it is worth not only to examine the overall range of EA, but the included reviews separately as well. The differences between the design of the included systematic reviews could be a potential source of heterogeneity, as they were aiming to capture different phenomena, such as elder abuse in community setting, in care setting, in rural areas, perpetrated by intimate partners, measured in specific geographical locations, etc. Some did perform meta-analysis, while others were reporting data ranges. They also used different techniques to assess the risk of bias, half of which (8/16) did not meet the criteria set by the modified AMSTAR-2 checklist, while the other half scored partial yes. Apart from the differences between reviews, other potential sources of heterogeneity could be the differences between primary studies (e.g. sample size, sampling method, data collection, EA definition, prevalence measure period). Reviews reported an association between abuse and geographical area (e.g. WHO regions, income levels) and cultural context.

The exhaustive search strategy we applied can be considered as one of the main strengths of this study. We searched eight electronic databases, covering a wide range of relevant disciplines, including biomedical-, health-, social- and behavioural sciences. Some of the databases apart from peer-reviewed journals also included citations for dissertations and book chapters, thus covering grey literature as well. To avoid language bias, neither our search strategy, nor the inclusion criteria included language restrictions. By overviewing texts in Chinese and Portuguese, we were able to increment the number of included systematic reviews by three. In addition, by not excluding systematic reviews of special populations of elderly (disabled, dementia), we were able to broaden the spectrum of the included evidence, while by reporting those separately from the other reviews we aimed to capture a prevalence estimate generalizable to the whole population.

One of the limitations of our review is that the quality appraisal instrument we used (AMSTAR-2) was primarily designed to evaluate systematic reviews of clinical trials.28 A modification of the original checklist was necessary for our research. AMSTAR-2 for example does not have any item to measure if systematic reviews reported the sampling methods used by the primary studies, which in prevalence studies is equally important to research design. In our modified checklist, we included this aspect in the assessment of risk of bias as a subitem. We must also note that while AMSTAR-2 evaluates the quality of systematic reviews, it does not evaluate the quality of the included primary studies. The overall evaluation of the included reviews depended on the number of critical weaknesses, not on the global score. As seen above, none of the review authors provided a list of excluded studies after full-text reading, and neither reported the funding of the primary studies. It is important to interpret the acquired estimates of prevalence data with caution, because of the low confidence in the results of the included reviews (in most cases assessed as “critically low”, and in two cases as “low”). We also acknowledge that subjectivity is always involved in critical appraisal by its nature, and other authors might have gotten different results using the same checklist. The low quality of the included reviews is one of the main limitations of our overview. Data extraction revealed that some authors even reported their results with contradictory data, a mistake that should be avoided in scientific writing (see footnotes of Table 1). AMSTAR-2 – which is a checklist to evaluate methodology – did not assess these trivial mistakes. Another difficulty we encountered during our research was defining systematic reviews. During our screening for relevant studies we excluded some reviews that were denominated as systematic reviews by the authors,47,48 however, they did not meet our operational definition detailed in the “Methods” section. We also identified some studies that were originally not published as systematic reviews but met our inclusion criteria. In the latter case, terms like “review”42 or “analytic review”41 were used. We recommend authors and journals to use an operational definition based on an expert consensus when we talk about systematic reviews.49

Despite the high variation in the results, we can conclude that EA is an alarmingly frequent phenomenon, and according to Yon et al.3 it affects 141 million people on a global level. With the ageing of the global population, authors predict a further rise in the magnitude of the problem. The fact that the transcendence and public health impact of the problem keeps being high despite the recent attention of the scientific community, should be a call for action for policymakers. As we saw, EA affects elderly people both in the community and the healthcare setting, and as the complex problem it is, it requires a multidisciplinary solution from experts in various areas.50 We would like to emphasize the importance of primary care providers and family physicians in this process, as they are in frequent contact with seniors, and they often build a deep relationship of trust with them.51 The education of health care professionals on the matter must be bettered both in the curricular and institutional levels, and population wide prevention strategies and screening programmes based on scientific evidence should be developed and implemented. We think primary care physicians and nurses will have a key role in such strategies.

Although we can consider that the phenomenon is widely studied (between the years 2007 and 2022 we identified 16 systematic reviews and 136 primary studies), there are still research gaps. Primary studies from low- and middle-income countries were reported to be scarce. In regions where the phenomenon is under-researched, there is a need for reliable primary studies using validated instruments. In the future, already existing systematic reviews should be updated with recent findings. We only identified one review focusing specifically on the general population in the institutional setting,14 according to which institutional abuse is also widespread, but under-researched. Regarding the methodological aspects of evidence synthesis methods, our recommendation for future research is to make a new instrument or a validated adaptation of AMSTAR-2 for prevalence studies. As we observed, poor reporting of findings was also a common problem, including data discrepancies. The solution to better the quality of reporting would be to strengthen the integrity of biomedical research. We further endorse the rising attention of the scientific community in recent years dedicated to the development of integrity guidelines, which could help authors to reduce erroneous writing.52–54

ConclusionsThis umbrella review is the first overview of systematic reviews measuring the prevalence of EA, and identifies important research gaps and implications for decision-makers. It demonstrates clearly that EA is an alarmingly frequent problem, although the exact prevalence data is hard to estimate, due to the overall low quality of the identified systematic reviews. Prevalence was different throughout the subtypes of EA, neglect being the most common form, followed by psychological-, financial-, physical- and sexual abuse. Evidence showed that the problem of elder abuse in care setting is just as relevant as in the community.

Our results imply that the education of health care professionals on the matter, and the prevention and early detection of EA should be bettered, ideally starting at the level of primary health care.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.