To assess the attitude of senior citizens towards the newly approved respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines using a novel survey instrument specifically tailored for this purpose.

Material and methodsBased on a literature review on vaccination attitude towards respiratory viruses (SARS-CoV-2 and influenza), 15 items were tested for content, face, and construct validity. Data collection nvolved face-to-face interviews among individuals aged 50 years or older in Jordan during May–June 2024. Construct validity was assessed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on principal component analysis.

ResultsA total of 231 respondents formed the final sample. The EFA showed that 5 constructs explained 71.9% of the variance in attitude to RSV vaccination. These constructs were labeled Fear, Information, Accessibility, Benefit, and Conspiracy. The acceptance of a safe and effective RSV vaccine if provided free-of-charge was observed among 55.4% of the participants (n = 128), while 16.0% were hesitant (n = 37), and 28.6% were resistant (n = 66). Applying the 5 RSV vaccine attitude constructs, demographic data, and vaccination history into the multivariate analysis, a higher RSV vaccine acceptance was found among elderly individuals with lower monthly incomes, a history of higher vaccine uptake, agreement with the Benefit construct, and disagreement with the Fear construct.

ConclusionsThis study developed an initial survey instrument to assess the attitudes of senior citizens towards the newly approved RSV vaccines. Further testing across diverse settings is necessary to evaluate the barriers and motivators influencing attitude to RSV vaccination. This effort is crucial to reduce the burden of RSV disease among the elderly.

Evaluar la actitud de las personas mayores hacia las vacunas recientemente aprobadas frente al VRS utilizando un instrumento de encuesta nuevo específicamente diseñado para este fin.

Material y métodosSobre la base de una revisión de la literatura sobre la actitud de la vacunación hacia los virus respiratorios (SARS-CoV-2 y gripe), se probaron 15 ítems en términos de contenido, aspecto y validez del constructo. La recopilación de los datos incluyó entrevistas presenciales entre individuos de 50 años de edad, o más, en Jordania durante los meses de mayo a junio de 2024. La validez del constructo se evaluó mediante un análisis factorial exploratorio (AFE) basado en el análisis del componente principal.

ResultadosLa muestra final se compuso de un total de 231 respondedores. El AFE reflejó que cinco constructos explicaron el 71,9% de la varianza en términos de actitud hacia la vacuna frente al VRS. Dichos constructos fueron etiquetados como Miedo, Información, Accesibilidad, Beneficio y Conspiración. La aceptación de una vacuna segura y efectiva frente al VRS, de ser esta gratuita, se observó en el 55,4% de los participantes (n = 128), mientras que el 16% era reacio (n = 37) y el 28,6% resistente (n = 66). Aplicando los cinco constructos de actitud de la vacuna frente al VRS, los datos demográficos y la historia de vacunación al análisis multivariante, se encontró una mayor aceptación de la vacuna frente al VRS entre los individuos mayores con menores ingresos mensuales, historia de mayor captación de vacunas, acuerdo con el constructo Beneficio y desacuerdo con el constructo Miedo.

ConclusionesEste estudio desarrolló un instrumento de encuesta inicial para evaluar las actitudes de las personas mayores hacia las vacunas recientemente aprobadas contra el VRS. Son necesarias más pruebas en diversos ámbitos para evaluar las barreras y los factores motivadores que influyen en la actitud hacia la vacuna contra el VRS. Dicho esfuerzo es esencial para reducir la carga de la enfermedad por VRS entre las personas mayores.

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections represent a significant public health concern.1,2 This concern is related to the burden of RSV as a respiratory pathogen that can lead to severe respiratory illness.3 RSV infections are particularly serious among vulnerable populations such as infants, young children, and the elderly (aged 60 years and above).4,5

Sufficient evidence has shown that RSV infections in individuals over 60 years can lead to severe outcomes.5,6 These feared sequelae include pneumonia, exacerbations of chronic pulmonary diseases (e.g., asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), hospitalization, and even death.5,6 The incidence of RSV-associated hospitalizations in the elderly highlights the substantial health burden posed by the virus.2,7 Additionally, the economic impact of RSV disease is considerable, with increased healthcare costs from hospital admissions, diagnostics, and prolonged medical care.8

One of the challenges in managing RSV in the elderly is the difficulty in accurate and timely diagnosis.9 This challenge primarily stems from symptoms of RSV infection mimicking those of other respiratory viruses, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis.6 Moreover, the effectiveness of antiviral treatments for RSV in adults remains limited, and management is primarily supportive.10 This highlights the need for preventive strategies, notably vaccination, to mitigate the impact of RSV in this vulnerable population.6

The historical lack of an effective vaccine against RSV represented a critical public health gap.11 In a landmark development in 2023, 2 novel RSV vaccines were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in the elderly (GSK Arexvy and Pfizer Abrysvo).6 The approval of these RSV vaccines followed years of extensive clinical trials which showed high efficacy and safety profiles.12–14

The approval of RSV vaccines represents an opportunity to reduce RSV-related morbidity and mortality in geriatric healthcare.15 However, the anticipated success of an effective and safe vaccine depends on its acceptance by the target population.16 Thus, accurate characterization of vaccine acceptance among the elderly in the context of RSV vaccination appears essential. Previous studies highlighted considerable hesitancy/resistance to vaccines for respiratory viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza across various global demographics.17,18 Vaccination hesitancy was particularly pronounced in the Middle East countries including Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic.19 Hence, understanding the factors which could influence RSV vaccine acceptance in Jordan appears critical to proactively address potential barriers to the newly approved RSV vaccines.

Vaccine hesitancy in elderly populations may be influenced by specific concerns about vaccine safety, efficacy, and cost as well as broader sociocultural and personal factors.20 Unraveling the determinants of vaccination attitude is essential to develop effective interventions aimed to enhance vaccine uptake.21

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to develop and validate a survey instrument specifically designed to assess RSV vaccine acceptance and its influencing factors among individuals aged 50 years or older in Jordan. By developing this survey instrument tool, we aimed to address the unique, context-specific attitudes towards RSV vaccination in this particular population and fill a gap in available instruments assessing RSV vaccine attitudes in the elderly. Ultimately, our work sought to contribute a validated tool to support the national and global public health strategies aimed at reducing the burden of RSV disease in older adults, aligning with broader initiatives in disease prevention and health promotion.

Material and methodsStudy design and participantsThis study was based on an exploratory, cross-sectional design to validate a novel survey instrument intended to assess RSV vaccine acceptance among the elderly population (aged 50 years or older) in Jordan. The study eligibility criteria included age 50 years or older, being a resident of Jordan, and fluency in Arabic. The decision to include individuals aged 50 years or older as participants in a study focusing on a vaccine approved for those aged 60 and older was related to the following considerations. This pre-emptive approach of extending the study age range to include those in their 50s, enable gaining early insights into the attitudes of individuals who are approaching the eligible age for RSV vaccination. Thus. the insights gained from including those individuals can help to shape early intervention strategies and educational campaigns tailored to those soon to be eligible for RSV vaccination.

Ethical considerationsThe study adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the School of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University (ASU), with the approval number 2024-PHA-21 granted on 20 May 2024. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the permission obtained by the IRB.

Survey instrument developmentThe questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of literature focusing on vaccine attitude in the elderly in the context of COVID-19 and influenza vaccination.20,22–28 The items were designed to capture a broad spectrum of attitudes, beliefs, and intentions related to the RSV vaccine in particular and vaccination in general. The survey instrument also assessed the demographic and health status of the participants to explore possible correlations with RSV vaccine acceptance.

These variables included: (1) age; (2) sex; (3) marital status; (4) monthly income of household; (5) education; (6) occupation; (7) place of residence; (8) history of chronic disease; (9) history of tobacco smoking; (10) history of COVID-19 vaccine uptake; and (11) history of influenza vaccine uptake. Then, the following item was introduced to assess previous knowledge of RSV: “Have you heard of RSV before the study?”

For the survey items assessing RSV vaccine attitude, the initial scale comprised 15 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: strongly agree, agree, neutral/no opinion, disagree, and strongly disagree. These initial items covered the following dimensions deemed critical by the 2 senior authors (M.S. and M.B.) to confirm comprehensive coverage of the relevant themes identified in existing literature: vaccine concerns, information-seeking behavior, constraints to vaccination, perceived benefits of vaccination, and general vaccination conspiracy beliefs. Face validity was verified by 2 microbiologists with experience in survey research, to ensure that the questionnaire was tailored to the objectives of the study. To accommodate the linguistic and cultural context of the participants, all items were developed in Arabic and subsequently back-translated into English by bilingual authors (M.S. and M.B.) to ensure the preservation of meaning across translations.

Construct validity was assessed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), to identify and confirm the underlying dimensions of RSV vaccine acceptance in the target population. The reliability of the survey was quantitatively assessed by computing Cronbach's α for each dimension identified through EFA. Prior to the study, a pilot test was conducted with five senior citizens (age range: 55–74 years) to evaluate the clarity of the questionnaire items. Feedback obtained from this preliminary group led to minor modifications to enhance the clarity of the survey items.

Finally, a specific item was used to assess attitude to the newly approved RSV vaccines assessed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree, agree, neutral/no opinion, disagree, to strongly disagree. The exact phrasing of the item was: “If RSV vaccination for older people is safe, effective, and freely available in Jordan, I would be willing to get vaccinated”.

Data collectionData collection was conducted via structured face-to-face interviews by the first 5 authors, utilizing the finalized survey instrument. To ensure consistency across data collection, interviewers underwent training on the standardized administration of the survey. This training included techniques to maintain neutrality during the interviews and to rigorously address participant privacy and data security concerns. The interviews were conducted at Outpatient Clinics at Jordan University Hospital in Amman, Jordan, using convenience sampling to recruit participants who were visitors during May–June 2024.

Sample size calculationConsidering the need for expedited yet robust analysis, we aimed for a sample size of 150 participants. This target facilitated a robust and expedited analysis using EFA, achieving a participant-to-item ratio of 10:1, based on the 15 survey items to allow for validation of the novel survey instrument.29

Statistical and data analysisAll analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Initial data characterization involved descriptive statistics with mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range, IQR) for the scale variable (age). To assess the construct validity and explore the underlying factor structure of the survey instrument, EFA was employed using principal component analysis for extraction. The factor rotation method selected was Direct Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization and a delta setting of 0.1, optimizing the ability to detect correlated latent constructs. An eigenvalue cut-off of 1.0 was applied to determine factor retention. The statistical adequacy of the data for conducting EFA was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett test of sphericity.

The willingness to get RSV vaccination was dichotomized into 2 categories: The vaccine acceptance group comprising those who responded “agree” or “strongly agree” to receive the RSV vaccine, and the vaccine hesitancy/resistance group comprising those who responded “strongly disagree”, “disagree” or were neutral or had no opinion regarding the RSV vaccine. The “vaccine uptake score” was calculated by summing the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses and influenza vaccine uptake, with responses coded as zero for “no” or “I do not know” and one for “yes”. This vaccine uptake score was then dichotomized into 2 levels: low (0–2) and high (3–4), to enable a simplified analysis of vaccine uptake history.

The scores for each RSV vaccine attitude scale were assigned as follows: strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neutral/no opinion = 3, agree = 4, and strongly agree = 5. Reverse coding was conducted for the items denoting a negative attitude. Finally, the scores for each RSV vaccine attitude scale construct were normalized by dividing the total scores by the number of items, creating a scale ranging from 1 to 5, segmented into 3 categories: 1–2.33 (disagreement), 2.34–3.67 (neutral), and 3.68–5 (agreement).

To examine the associations between categorical variables, the chi-squared (χ2) test was used. For the scale variable (age) association with RSV vaccine acceptance, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was conducted based on non-normal distribution of age as indicated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (P < .001). Variables demonstrating a potential association with RSV vaccine acceptance at a threshold of P < .100 in univariate analysis were advanced to multivariate analysis to control for possible confounders. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of RSV vaccine acceptance, with statistical significance set at P < .050.

ResultsDescription of the study sampleA total of 261 individuals were approached with 30 who did not consent to participate (11.5%). Thus, the final sample comprised a total of 231 individuals. The general features of the study sample are shown in Table 1. The study sample comprised individuals with an average age of 61 years, predominantly female. Most participants were married, earned a monthly income of ≤1000 Jordanian dinars, held a college degree, and were unemployed or retired. The majority were non-smokers with a history of chronic disease and resided in the Central region of Jordan. Regarding vaccination history, most reported the uptake of 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccines, but only slightly over one-fifth reported the uptake of the influenza vaccine. Notably, only 28.6% of participants were aware of RSV prior to this study (Table 1).

General features of the study sample (N = 231).

| Variable | Category | Nf (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Mean±SDa, Median (IQRb) | 60.6 ± 7.1, 60 (55–64) | |

| Sex | Male | 96 (41.6) |

| Female | 135 (58.4) | |

| Marital status | Married | 192 (83.1) |

| Single/divorced/widow/widower | 39 (16.9) | |

| Monthly income of household | ≤1000 JODe | 172 (74.5) |

| >1000 JOD | 59 (25.5) | |

| Educational level | High school or less | 88 (38.1) |

| Undergraduate or postgraduate | 143 (61.9) | |

| Occupation | Unemployed/retired | 181 (78.4) |

| Employed | 50 (21.6) | |

| Place of residence | Central region | 220 (95.2) |

| North/South | 11 (4.8) | |

| History of chronic disease | No | 69 (29.9) |

| Yes | 162 (70.1) | |

| History of smoking | No | 130 (56.3) |

| Ex-smoker | 36 (15.6) | |

| Yes | 65 (28.1) | |

| COVID-19c vaccine doses received | 0 | 17 (7.4) |

| 1 | 6 (2.6) | |

| 2 | 141 (61.0) | |

| 3 | 65 (28.1) | |

| 4 | 2 (0.9) | |

| History of influenza vaccination | No/I do not know | 183 (79.2) |

| Yes | 48 (20.8) | |

| Heard of RSVd before the study | Yes | 66 (28.6) |

| No | 165 (71.4) |

In EFA, the KMO measure was 0.810 indicative of a very good level of sampling adequacy for factor analysis. Bartlett test of sphericity yielded an approximate χ2 value of 1465.9 (P < .001), which supported the presence of relationships among the survey items, confirming that the items were intercorrelated and suitable for structure detection through EFA.

The EFA highlighted 5 significant components that cumulatively explained 71.9% of the total variance. The first deduced construct showed a Cronbach's α of 0.838, and this construct was labeled “Fear” since the 3 items were related to direct concerns about vaccination including the RSV vaccine.

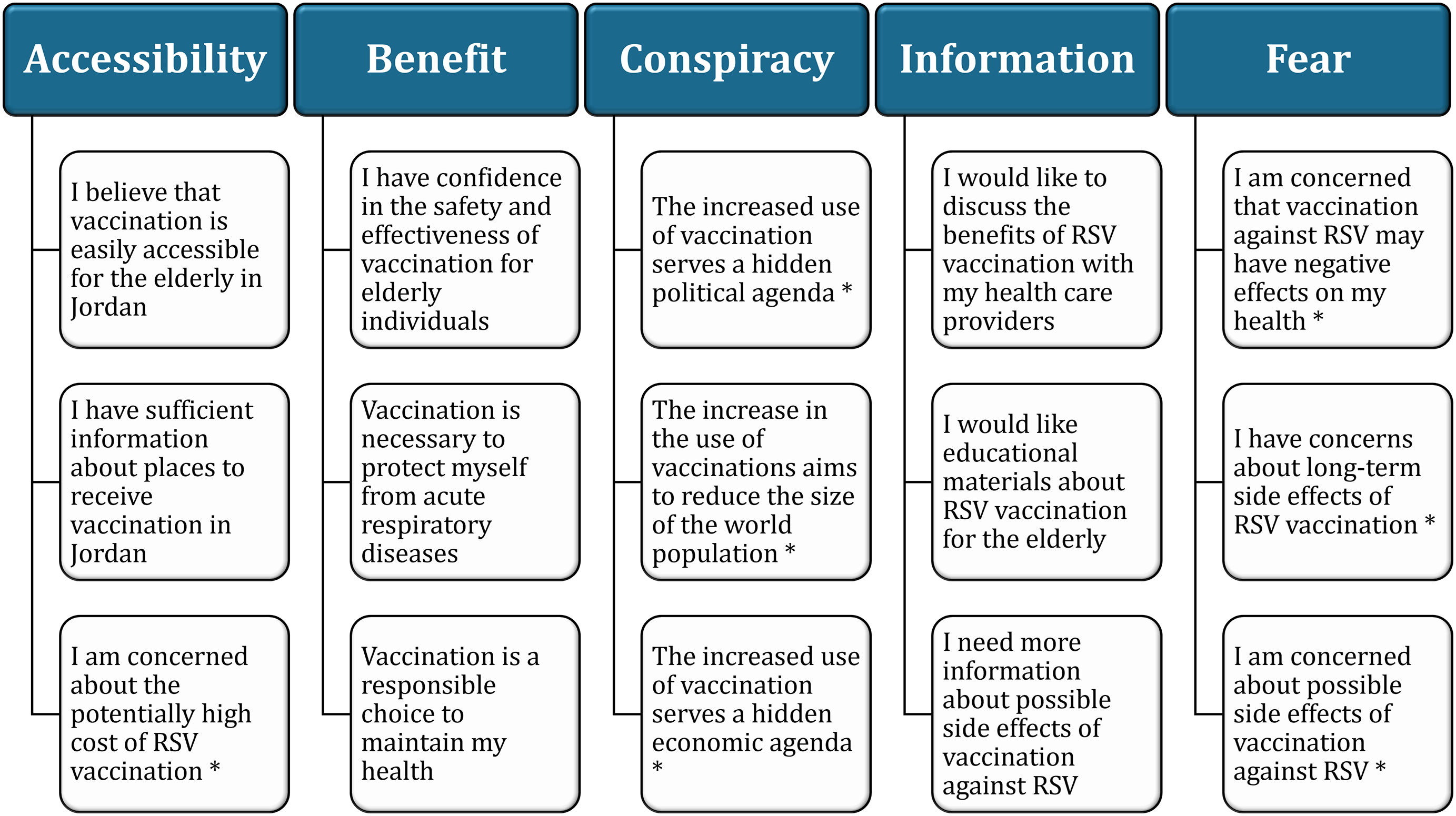

The second construct with a Cronbach's α of 0.792 captured 3 items related to informational needs as was labeled “Information”. The third construct with a Cronbach's α of 0.571 involved items on the accessibility and logistical aspects of vaccination and was termed “Accessibility”. The fourth construct with a Cronbach's α of 0.872 involved 3 items on the perceived benefits from RSV vaccination was termed “Benefit”. Finally, the fifth construct with a Cronbach's α of 0.774 comprised 3 items on the conspiracy beliefs related to vaccination and thus was labeled “Conspiracy”. The full items and constructs of the final scale for attitude of seniors to RSV vaccination are shown in Fig. 1.

The finalized scale of the instrument inferred to assess the attitude of senior citizens to RSV vaccination. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus. The items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral/no opinion, disagree, and strongly disagree). Items with reverse scoring is marked with an asterisk.

As shown in Fig. 2, the acceptance of a safe and effective RSV vaccine if provided free-of-charge was observed among 55.4% of the participants (n = 128), while 16.0% were hesitant (n = 37), and 28.6% were resistant (n = 66).

In univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance. Participants with a lower monthly income showed an RSV vaccine acceptance rate of 59.3% (n = 102) compared to a rate of 44.1% (n = 26) among those with a higher income (P = .042, χ2 = 4.127). Additionally, the participants with higher vaccine uptake scores showed a significantly higher RSV vaccine acceptance rate at 68.1% (n = 64) as opposed to a rate of 46.7% (n = 64) among those with lower vaccine uptake scores (P = .001, χ2 = 10.304, Table 2).

Variables associated with attitude to RSV vaccination in the study sample.

| Variable | Category | RSV vaccine attitude | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance | Hesitancy/resistance | |||

| Ne (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age | Mean ± SDc | 60.1 ± 6.9 | 61.1 ± 7.3 | .292 |

| Sex | Male | 59 (61.5) | 37 (38.5) | .119 |

| Female | 69 (51.1) | 66 (48.9) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 111 (57.8) | 81 (42.2) | .103 |

| Single/divorced/widow/widower | 17 (43.6) | 22 (56.4) | ||

| Monthly income of household | ≤1000 JODd | 102 (59.3) | 70 (40.7) | .042 |

| >1000 JOD | 26 (44.1) | 33 (55.9) | ||

| Educational level | High school or less | 52 (59.1) | 36 (40.9) | .377 |

| Undergraduate or postgraduate | 76 (53.1) | 67 (46.9) | ||

| Occupation | Unemployed/retired | 104 (57.5) | 77 (42.5) | .234 |

| Employed | 24 (48.0) | 26 (52.0) | ||

| Place of residence | Central region | 123 (55.9) | 97 (44.1) | .496 |

| North/South | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | ||

| History of chronic disease | No | 35 (50.7) | 34 (49.3) | .350 |

| Yes | 93 (57.4) | 69 (42.6) | ||

| History of smoking | No | 75 (57.7) | 55 (42.3) | .657 |

| Ex-smoker | 20 (55.6) | 16 (44.4) | ||

| Yes | 33 (50.8) | 32 (49.2) | ||

| Vaccine uptake scorea | 0–2 | 64 (46.7) | 73 (53.3) | .001 |

| 3–4 | 64 (68.1) | 30 (31.9) | ||

| Heard of RSVb before the study | Yes | 39 (59.1) | 27 (40.9) | .477 |

| No | 89 (53.9) | 76 (46.1) | ||

For the constructs of the RSV vaccination attitude, 4 out of 5 constructs showed statistically significant associations with RSV vaccine acceptance as follows. RSV vaccine acceptance was associated with a higher disagreement with the Fear construct, a higher agreement with the Information construct, a higher agreement with the Benefit construct, and a higher disagreement with the Conspiracy construct (Table 3).

The association of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccination scale constructs with attitude to RSV vaccination.

| Variable | Category | RSV vaccine attitude | P value, χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance | Hesitancy/resistance | |||

| Na (%) | N (%) | |||

| Fear construct category | Agreement | 70 (42.7) | 94 (57.3) | <.001, 37.090 |

| Neutral | 37 (86.0) | 6 (14.0) | ||

| Disagreement | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | ||

| Information construct category | Disagreement | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) | <.001, 19.548 |

| Neutral | 25 (42.4) | 34 (57.6) | ||

| Agreement | 98 (65.3) | 52 (34.7) | ||

| Accessibility construct category | Disagreement | 18 (43.9) | 23 (56.1) | .202, 3.203 |

| Neutral | 70 (56.0) | 55 (44.0) | ||

| Agreement | 40 (61.5) | 25 (38.5) | ||

| Benefit construct category | Agreement | 102 (79.7) | 26 (20.3) | <.001, 71.576 |

| Neutral | 20 (32.3) | 42 (67.7) | ||

| Disagreement | 6 (14.6) | 35 (85.4) | ||

| Conspiracy construct category | Agreement | 45 (40.2) | 67 (59.8) | <.001, 25.065 |

| Neutral | 57 (64.0) | 32 (36.0) | ||

| Disagreement | 26 (86.7) | 4 (13.3) | ||

Multivariate analysis using multinomial logistic regression with vaccine hesitancy/resistance as the reference showed a Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.515 indicating an acceptable fitness of the model. The following variables were associated with higher odds of RSV vaccine acceptance. First, a lower monthly income was significantly associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance (aOR: 3.677, 95% CI: 1.633–8.279, P = .002, Table 4). Additionally, higher vaccine uptake score was associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance (aOR: 2.177, 95% CI: 1.063–4.456, P = .033, Table 4). Furthermore, neutral attitude in the Information construct was associated with lower RSV vaccine acceptance compared to agreement attitude to the Information construct (aOR: 0.387, 95% CI: 0.170–0.882, P = .024, Table 4). Finally, agreement with the Benefit construct was associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance compared to disagreement (aOR: 12.863, 95% CI: 4.221–39.200, P < .001, Table 4).

The variables association with RSV vaccine acceptance in the study sample.

| RSVa vaccine acceptance vs. hesitancy/resistance | aORd (95% CIe) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly income of household ≤1000 JODb | 3.677 (1.633–8.279) | .002 |

| Monthly income of household <1000 JOD | Ref. | |

| Vaccine uptake scorec: 3–4 | 2.177 (1.063–4.456) | .033 |

| Vaccine uptake score: 0–2 | Ref. | |

| Fear construct: Agreement | 0.258 (0.053–1.243) | .091 |

| Fear construct: Neutral | 1.613 (0.273–9.520) | .598 |

| Fear construct: Disagreement | Ref. | |

| Information construct: Disagreement | 0.56 (0.141–2.22) | .410 |

| Information construct: Neutral | 0.387 (0.170–0.882) | .024 |

| Information construct: Agreement | Ref. | |

| Benefit construct: Agreement | 12.863 (4.221–39.200) | <.001 |

| Benefit construct: Neutral | 2.520 (0.792–8.022) | .118 |

| Benefit construct: Disagreement | Ref. | |

| Conspiracy construct: Agreement | 0.408 (0.089–1.863) | .247 |

| Conspiracy construct: Neutral | 0.497 (0.113–2.193) | .356 |

| Conspiracy construct: Disagreement | Ref. |

Statistically significant P values are highlighted in bold style.

The present study employed an EFA approach to elucidate the underlying constructs which could influence RSV vaccine attitudes among elderly individuals. This analysis revealed 5 key constructs: Fear, Information, Accessibility, Benefit, and Conspiracy, explaining a significant 72% of the variance in attitudes towards RSV vaccination. These findings pointed to the complex interplay of factors that would shape attitude to the newly approved RSV vaccines in the elderly. In turn, the utilization of this survey instrument can help to develop targeted interventions to enhance RSV vaccine uptake among senior citizens with subsequent reduction in RSV disease burden in this vulnerable group.

The relevant constructs for RSV vaccination attitude in this study aligned with established theories in health behavior, such as the Health Belief Model (HBM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).30 This emphasizes the role of beliefs, information, and perceived barriers in health-related decision-making including the acceptance of the novel RSV vaccines.

The first construct in this study was the “Accessibility” construct, which addressed the logistical barriers to vaccination such as availability and convenience. This construct has been shown as a crucial determinant of vaccine uptake according to the 5C model of vaccine acceptance conceived by Betsch et al.31 Accessibility is particularly relevant in settings with limited resources or where healthcare infrastructure struggles to support broad vaccine distribution and administration effectively. Fuller et al., provided evidence of how these logistical barriers, including cost and transportation, critically influence vaccination decisions among older adults.20 This suggests that improving physical access to vaccination services could substantially increase RSV vaccine acceptance among older adults.20,32

“Benefit” emerged as the second relevant construct in the study. This construct involves the perceived advantages of getting vaccinated against RSV in the elderly. This result suggests that the clear and more tangible demonstration of RSV vaccine benefits would increase the likelihood of RSV vaccine acceptance. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a study by Thorpe et al. demonstrated that effective messaging strategies about potential vaccine side effects and efficacy significantly enhanced confidence and interest in vaccination among U.S. veterans and non-veterans.33

“Conspiracy” represented the third construct relevant for RSV vaccination attitude in this study. This involves the skepticism about vaccination and motives behind vaccine promotion, which can be a substantial barrier to vaccine uptake.34,35 This construct appears critical in the Middle East region where COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy was related to endorsing conspiracy beliefs.19

The fourth construct, “Information” emphasized the importance of clear communication about vaccine efficacy and side effects. This construct highlights the influence of recommendations from credible sources and healthcare providers in promoting RSV vaccination among senior citizens. Finally, the fifth construct termed “Fear” reflected the perceived risks associated with the RSV vaccine, such as potential side effects. This aligns with the HBM component of “perceived threats,” where fear can significantly inhibit preventive behaviors.30 For instance, studies on COVID-19 and influenza vaccines have demonstrated that safety concerns significantly reduce vaccine uptake.36,37

Scarce data currently exist regarding the RSV vaccine attitude among the elderly individuals. The most recent study by Haeder reported that 9% of seniors in the USA have already been vaccinated against RSV, while 42% were willing to receive the vaccine.38 In line with the findings of this study, Haeder showed that the reasons for RSV vaccine hesitancy included fear of side effects and a lack of information regarding the vaccine.38

Recent studies focused on the determinants of maternal attitude to RSV vaccination.39–42 This comes in light of the recent approval of maternal RSV vaccines to protect infants. The results of these studies pointed to some shared constructs with our study including the need for more information about the vaccine, concerns regarding RSV vaccine safety, vaccine conspiracies, and fear of the disease risks.39–42

In this study, the multivariate analysis provided additional insights into how different constructs influenced RSV vaccine acceptance in senior citizens. Agreement with the “Benefit” construct was strongly associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance. This aligns with TPB which postulate that perceived benefits are powerful motivators for adopting health behaviors.30 Thus, emphasizing the benefits of vaccination can significantly enhance RSV vaccine uptake.

Higher disagreement with the “Fear” construct was associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance. This result highlights the detrimental impact of concerns about side effects or vaccine-induced illness as shown by Haeder.38 Therefore, addressing these fears through targeted education that clarifies misconceptions and provides evidence-based information about vaccine safety is crucial to promote RSV vaccination among senior citizens.

The findings also indicated that a neutral attitude towards the Information construct correlates with lower RSV vaccine acceptance compared to a positive attitude. This suggests that ambivalence or insufficient information can be as significant a barrier to RSV vaccine uptake. Thus, ensuring that individuals are well-informed and understand the information provided regarding RSV vaccination is a key measure to increase RSV vaccine acceptance.

A notable finding in this study was the association monthly income and RSV vaccine acceptance. Participants with lower monthly incomes showed significantly higher RSV vaccine acceptance rates compared to their higher-income counterparts. This result may seem counterintuitive; however, it can be rationalized by considering the relative value and perceived necessity of free healthcare services among lower-income groups. For individuals with limited financial resources, free vaccination—as phrased in the survey item assessing RSV vaccine acceptance—represents a health benefit increasing its perceived value. This tentative finding warrants further investigation considering the current evidence suggesting a lack of clear patterns regarding the socioeconomic differences in routine vaccination rates.43

In this study, higher vaccine uptake scores likely reflecting a general pro-vaccination attitude were significantly associated with higher RSV vaccine acceptance. This result suggests that individuals past experiences with vaccination can play an important role in their acceptance of novel vaccines. The role of previous vaccination history with more positive attitude to vaccination was shown among health professionals for monkeypox vaccination.44

Finally, in light of the exploratory nature of this study, we acknowledge several limitations that highlight the need for further validation of the survey instrument used. First, the study sample comprised 231 individuals, which potentially affects the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the sample may not fully represent the wider Jordanian community. Given the cross-sectional design of the study, we are also cautious about our ability to draw causal inferences from the data. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data introduced the risk of response biases, including social desirability bias, especially in the determination of past vaccination behavior.

Despite these limitations, the implications of the study findings can be important for public health strategies aiming to increase RSV vaccine uptake among senior citizens. Clear communication by health authorities and healthcare providers regarding the benefits of RSV vaccination and its safety can be crucial. Testing the survey instrument used in this study across different cultural, social, and healthcare contexts would solidify its reliability and validity and enrich the understanding of its applicability in varied populations. Building on our initial findings, future studies are recommended to provide more definitive insights to the global efforts in promoting RSV vaccination and public health readiness.

ConclusionsThe 5 constructs inferred in this study offered a unique lens to view the complexities of RSV vaccine attitudes among senior citizens. The findings provide actionable insights for public health strategies aimed at increasing RSV vaccine uptake. The multifaceted nature of RSV vaccine acceptance among the elderly individuals, emphasize the importance of addressing various factors in RSV vaccination program design. By understanding and targeting specific factors that influence vaccine attitudes, health authorities, and policymakers can develop more effective strategies to improve public health outcomes and combat the burden of RSV disease in the elderly.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics statementThe study was carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the School of Pharmacy, Applied Science Private University (ASU), with the approval number 2024-PHA-21 granted on 20 May 2024. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the permission obtained by the IRB.

Author contributionConceptualization: M.S.; Data Curation: M.A.-G., D.S., J.A.-H., L.O., R.A., M.B., M.S.; Formal Analysis: M.S.; Investigation: M.A.-G., D.S., J.A.-H., L.O., R.A., M.B., M.S.; Methodology: M.S.; Project administration: M.B., M.S.; Resources: M.S.; Supervision: M.S.; Validation: M.A.-G., D.S., J.A.-H., L.O., R.A., M.B., M.S.; Visualization: M.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: M.S.; Writing – Review & Editing: M.A.-G., D.S., J.A.-H., L.O., R.A., M.B., M.S.

We would like to thank Dr. Khaled Al-Salahat and Dr. Eyad Al-Ajlouni for their help in initial assessment of the survey.